The objective of this study was to determine if an oral ketamine mouth wash and expectorant, that may or may not rinse transmucosal fentanyl, was a safe and effective method to alleviate a series of various difficult to control orofacial pain of cancer origin.

Materials and methodsA prospective review was made of the medical charts of 20 patients, finding 8 patients who received ketamine mouthwash (40mg=4ml), 8 patients who received ketamine mouthwash and oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate 200mcg, and 4 patients with systemic opioids for refractory orofacial and mucositis pain.

ResultsOf the 20 patients, 16 had orofacial or mucositis pain refractory to a mixture of lidocaine and opioids. The effectiveness of ketamine mouthwash was 50% (8/16 patients). The combination of ketamine and/or fentanyl transmucosal had an analgesic efficacy of 94.1% (15/16 patients). The adverse effects were associated with the ketamine mouthwash; all side effects were transient and subsided when the ketamine mouthwash was stopped.

ConclusionKetamine mouthwash for orofacial pain due to cancer may be an effective treatment option. In cases of reported episodes of breakthrough pain, the combination of a ketamine mouthwash and oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate may be a viable treatment option in refractory mucositis pain.

Evaluar la efectividad de los enjuagues de ketamina asociados o no a fentanilo transmucoso en una serie de diversos dolores orofaciales de etiología neoplásica de difícil control analgésico.

Material y métodosEstudio prospectivo de 20 pacientes, con 8 pacientes que recibieron enjuagues de ketamina (40mg=4ml), 8 pacientes que recibieron ketamina asociada a citrato de fentanilo por vía transmucosa oral a dosis de 200 mcg y 4 pacientes con opiáceos sistémicos para el dolor orofacial y mucositis refractaria.

ResultadosUn total de16 de los 20 pacientes tenían dolor orofacial o mucositis refractaria al tratamiento con lidocaína y opiáceos. La tasa de éxito del empleo de enjuagues de ketamina fue del 50% (8/16 pacientes). La asociación ketamina y fentanilo transmucoso obtuvo una tasa de éxito del 94,1% (15/16 pacientes). Los efectos adversos se asocian al uso de la ketamina; todos los efectos secundarios fueron transitorios y desaparecieron cuando se suspendieron los enjuagues con ketamina.

ConclusiónLos enjuagues de ketamina son una opción eficaz para el tratamiento del dolor orofacial secundario al cáncer. En caso de presencia de episodios de dolor irruptivo recurrente, la asociación de ketamina en enjuague bucal y citrato de fentanilo oral transmucoso puede ser una opción viable en dolor refractario a otros tratamientos.

Pain in patients with cancer has a high prevalence.1 Pain is an essential aspect of oncologic diseases that must be treated as such, and its therapeutic management must be considered a priority as important as the underlying disease, given that pain and uncontrolled pain crisis can be as devastating as the oncologic disease itself.2,3 Temporary flare-ups significantly reduce patients’ quality of life and represent a difficult therapeutic challenge for clinicians. The term breakthrough pain was introduced by Portenoy and Hagen4 and it is defined as a sudden and temporary exacerbation of pain experienced on top of persistent, background, baseline pain that is stable and adequately controlled with major opioids. In our country, this term was renamed “breakthrough cancer pain” (BCP) based on an agreement document involving several scientific associations.5 BCP may be incidental (related to a specific triggering factor) or spontaneous. In several studies, BCP prevalence varies widely between 23% and 93%.6 Prevalence in Spain amounts to 41%, based on the study conducted by Gómez-Batiste et al.7

There are different types of opioids based on their release mechanism and duration of their analgesic effect. In the medical practice, the introduction of different rapid onset opioids (ROO) with early stage maximum effects, short action duration and reduced residual sedation episodes is an interesting choice for the treatment of BCP. In our country, several pharmaceutical forms of ROO-type drugs are available (tablets with an integrated oral applicator, sublingual tablets, effervescent oral tablets, and transmucosal intranasal fentanyl).

On the other hand, topical treatments can control pain locally, thus minimising systemic side effects. Therefore, several agents administrated in mouthwashes in the oral cavity for the treatment of oropharyngeal pain have been analysed. These include local anaesthetics, antihistamines, anti-inflammatory agents, opioids, n-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists, antimicrobial agents or combinations of these. In general, results were mainly limited by the short duration of pain relief obtained. NMDA receptors are widely distributed along the nervous system, and the peripheral administration of several NMDA receptor antagonist drugs has several anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive actions.8,9 There are several routes of administration of ketamine hydrochloride, which is an NMDA receptor antagonist.10–15

The objective of this study is to assess the effectiveness of ketamine (KTM) mouthwashes associated or not with transmucosal fentanyl (KTM+FENT) regarding several kinds of neoplastic-aetiology orofacial pains which are difficult to control with analgesics.

Materials and methodsProspective, not randomised and descriptive study conducted in a Chronic Pain Unit during 2008–2012 upon approval by the Ethics Committee.

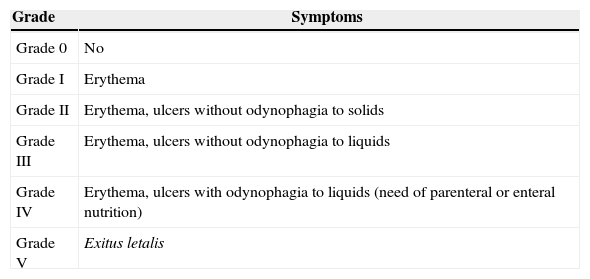

Inclusion criteria included the following: patients of age with a histologically confirmed cancer diagnosis and orofacial pain symptoms attributable to neoplasia or complications arising from its treatment, in patients receiving maintenance treatment with opioids for chronic cancer pain. Table 1 shows the classification of mucositis used in our Unit. Maintenance treatment is defined as an opioid based treatment of at least 60mg of oral morphine per day, 25mcg of transdermal fentanyl per hour, 30mg of oxycodone per day, 200mg of tapentadol per day or an equianalgesic dose of any other opioid during a week or more.

Classification of the grade of mucositis.

| Grade | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Grade 0 | No |

| Grade I | Erythema |

| Grade II | Erythema, ulcers without odynophagia to solids |

| Grade III | Erythema, ulcers without odynophagia to liquids |

| Grade IV | Erythema, ulcers with odynophagia to liquids (need of parenteral or enteral nutrition) |

| Grade V | Exitus letalis |

Source: World Health Organisation.26

Exclusion criteria included the following: patients not of age, with allergy or intolerance to ketamine hydrochloride, fentanyl or any other opioids, with history of any kind of drug addiction, uncontrolled high blood pressure, epilepsy, unstable ischaemic cardiopathy, cerebral expansive processes of any aetiology and concomitant treatment with monoamine oxidase inhibitors.

Ethical considerationsThe procedures carried out in this investigation complied with the ethical standards of the Human Experimentation Committee of our hospital and community, as well as the guidelines of the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki. Upon obtaining the informed consent from patients regarding study participation and publication of results, we have ensured the privacy and the confidentiality of patients.

Unit protocolAll patients were subject to an initial opioid dose titration stage, which involved increasing the opioid dose until pain control was achieved or until the onset of significant side effects. In these cases, there was an opioid rotation with subsequent dose adjustment and control of adverse effect re-onset. In those cases with poor control of orofacial pain or onset of adverse events, we began treatment with 4ml of KTM mouthwashes (10mg/ml) during 4–5min, and the degree of pain relief and the number and degree of side effects was assessed in this first administration. In those cases with a good analgesic response, families were offered 5–6 syringes of the product to carry out instillations at home every 8h. At 72h, patients were re-assessed. In cases where pain control and tolerance were considered appropriate, treatment at home with KTM syrup 100ml (10mg/ml) in Ora-Sweet, formulated by the Hospital Pharmacy Service of our centre, was prescribed. In cases with poor analgesic control or incidental pain crisis onset during the administration interval, transmucosal fentanyl 200μg was indicated. In cases with side effect onset, the concentration of KTM was reduced to 5mg/ml and transmucosal fentanyl was indicated.

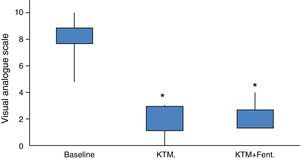

The success of the treatment was defined as pain relief above 75% in an visual analogue scale (VAS) compared to baseline VAS. Analgesic partial control was defined as a reduction in baseline pain of about 25–75%.

VariablesSeveral demographic variables, associated comorbidity, and neoplasia type and stage were assessed, and diagnoses were grouped based on the ICD-9 disease classification system, existence of previous surgery and type of surgery, local and systemic adverse events (respiratory depression, circulatory depression, low blood pressure, dizziness, drowsiness, headache, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, vasovagal reaction, vision abnormalities, rhinitis, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, constipation, dyspepsia, mouth dryness, cutaneous eruption, itching, flushing, hot flushes, asthenia, irritation in the injection site, anorexia, concentration difficulty and euphoria), baseline analgesic medication, onset time of pain symptoms, pain intensity based on an 11-point VAS, from 0 to 10 (where 0 is no pain and 10 is the worst imaginable pain), baseline opioid dose, aetiology, topography and characteristics of the pain.

After controlling the pain, the baseline opioid was progressively reduced and, upon stabilising the dose, several of the opioids used were converted to equianalgesic doses of morphine to assess the reduction in opioid consumption. The level of satisfaction of treatment administration was assessed. Then, a telephone interview or a clinical history revision was conducted to assess the progression 1, 3 and 6 months after the beginning of the treatment.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was carried out using the Stata® 7 software (Stata Corporation, Computing Resource Centre, College Station, Texas, U.S.A.). A descriptive analysis of the variables was carried out, and the distribution of their frequencies was calculated on a global scale. Normal distribution was assessed using the Kolomogorov–Smirnov test, and the treatment success and failure distribution was compared among patients of the series as to observed variables and their possible association using, for quantitative variables, the Student's t test or the Kruskall–Wallis test, if there were no equal variances, and, for qualitative variables, the square chi test (Chi2) with Yates correction or Fischer's test. A new significance level of p<0.05 was determined for all statistical data used. The efficiency of the different treatment options for cancer orofacial pain and adverse events was assessed.

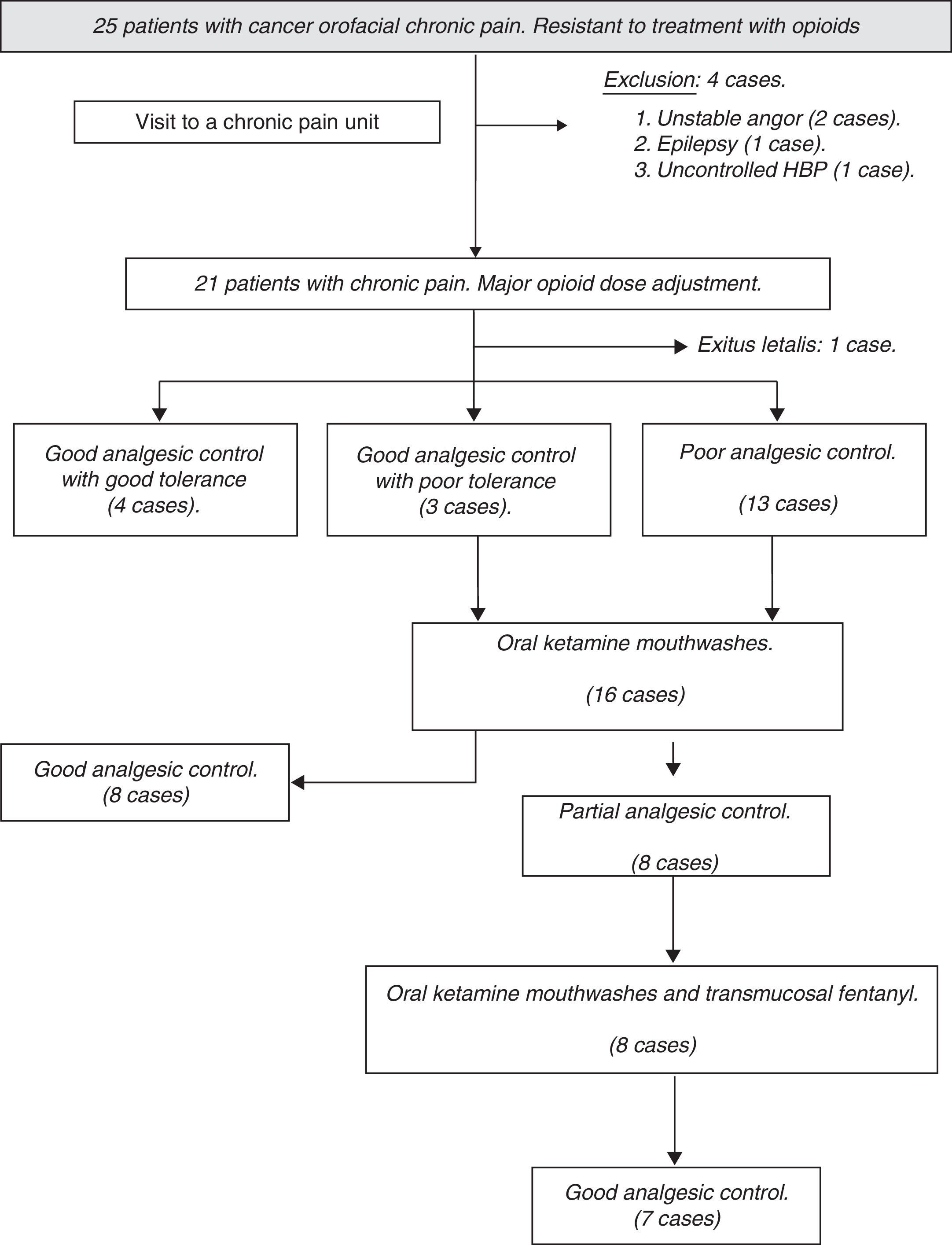

ResultsThe number of patients recruited during the study period was 25, excluding, from the onset, 4 cases due to associated medical comorbidity where KTM administration was contraindicated. After that, upon upward titration or rotation with opioids, it was possible to achieve an adequate control of pain without side effects in 4 cases, so the KTM protocol was not started. During follow-up, another patient was excluded due to exitus letalis during the study period. The flow chart of patients during follow-up and the causes of exclusion from the study are shown in Fig. 1.

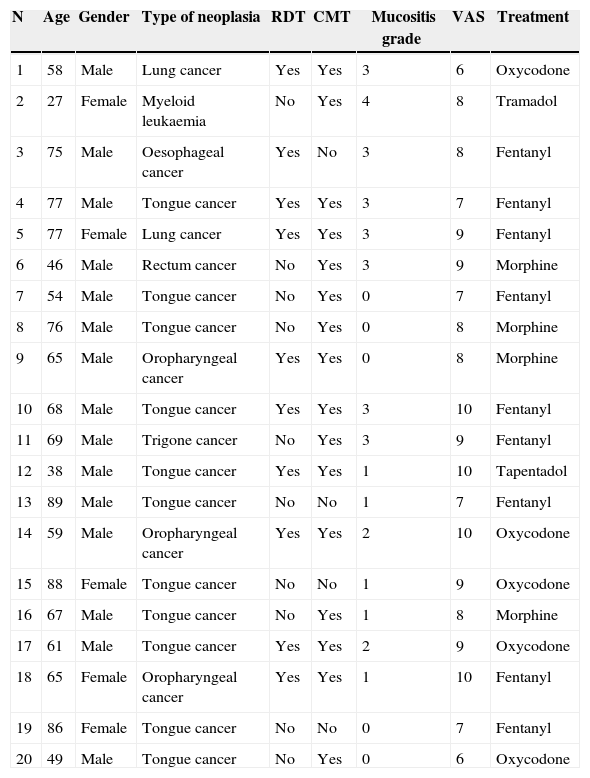

The study cohort was finally made up of 20 patients, of which 16 began the protocol with KTM mouthwashes. The mean age of the cohort was 64.70±16.37 years, mostly male patients (75%). The main demographic characteristics of the series are shown in Table 2. Due to the study design, the baseline pain estimated using a VAS was of high intensity, with values around 8.25±1.29 (6–10 range). Baseline opioid analgesic consumption at the beginning of the treatment with KTM or KTM+FENT mouthwashes was 224±44mg of oral morphine, which was reduced to 153±41mg of oral morphine (p<0.001). The decrease in opioid consumption was estimated at 32%.

Demographic characteristics of the clinical cases series.

| N | Age | Gender | Type of neoplasia | RDT | CMT | Mucositis grade | VAS | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58 | Male | Lung cancer | Yes | Yes | 3 | 6 | Oxycodone |

| 2 | 27 | Female | Myeloid leukaemia | No | Yes | 4 | 8 | Tramadol |

| 3 | 75 | Male | Oesophageal cancer | Yes | No | 3 | 8 | Fentanyl |

| 4 | 77 | Male | Tongue cancer | Yes | Yes | 3 | 7 | Fentanyl |

| 5 | 77 | Female | Lung cancer | Yes | Yes | 3 | 9 | Fentanyl |

| 6 | 46 | Male | Rectum cancer | No | Yes | 3 | 9 | Morphine |

| 7 | 54 | Male | Tongue cancer | No | Yes | 0 | 7 | Fentanyl |

| 8 | 76 | Male | Tongue cancer | No | Yes | 0 | 8 | Morphine |

| 9 | 65 | Male | Oropharyngeal cancer | Yes | Yes | 0 | 8 | Morphine |

| 10 | 68 | Male | Tongue cancer | Yes | Yes | 3 | 10 | Fentanyl |

| 11 | 69 | Male | Trigone cancer | No | Yes | 3 | 9 | Fentanyl |

| 12 | 38 | Male | Tongue cancer | Yes | Yes | 1 | 10 | Tapentadol |

| 13 | 89 | Male | Tongue cancer | No | No | 1 | 7 | Fentanyl |

| 14 | 59 | Male | Oropharyngeal cancer | Yes | Yes | 2 | 10 | Oxycodone |

| 15 | 88 | Female | Tongue cancer | No | No | 1 | 9 | Oxycodone |

| 16 | 67 | Male | Tongue cancer | No | Yes | 1 | 8 | Morphine |

| 17 | 61 | Male | Tongue cancer | Yes | Yes | 2 | 9 | Oxycodone |

| 18 | 65 | Female | Oropharyngeal cancer | Yes | Yes | 1 | 10 | Fentanyl |

| 19 | 86 | Female | Tongue cancer | No | No | 0 | 7 | Fentanyl |

| 20 | 49 | Male | Tongue cancer | No | Yes | 0 | 6 | Oxycodone |

VAS: baseline pain measurement using a visual analogue scale; mucositis grade: classification of the grade of mucositis; N: case number; CMT: chemotherapy treatment; RDT: radiotherapy treatment.

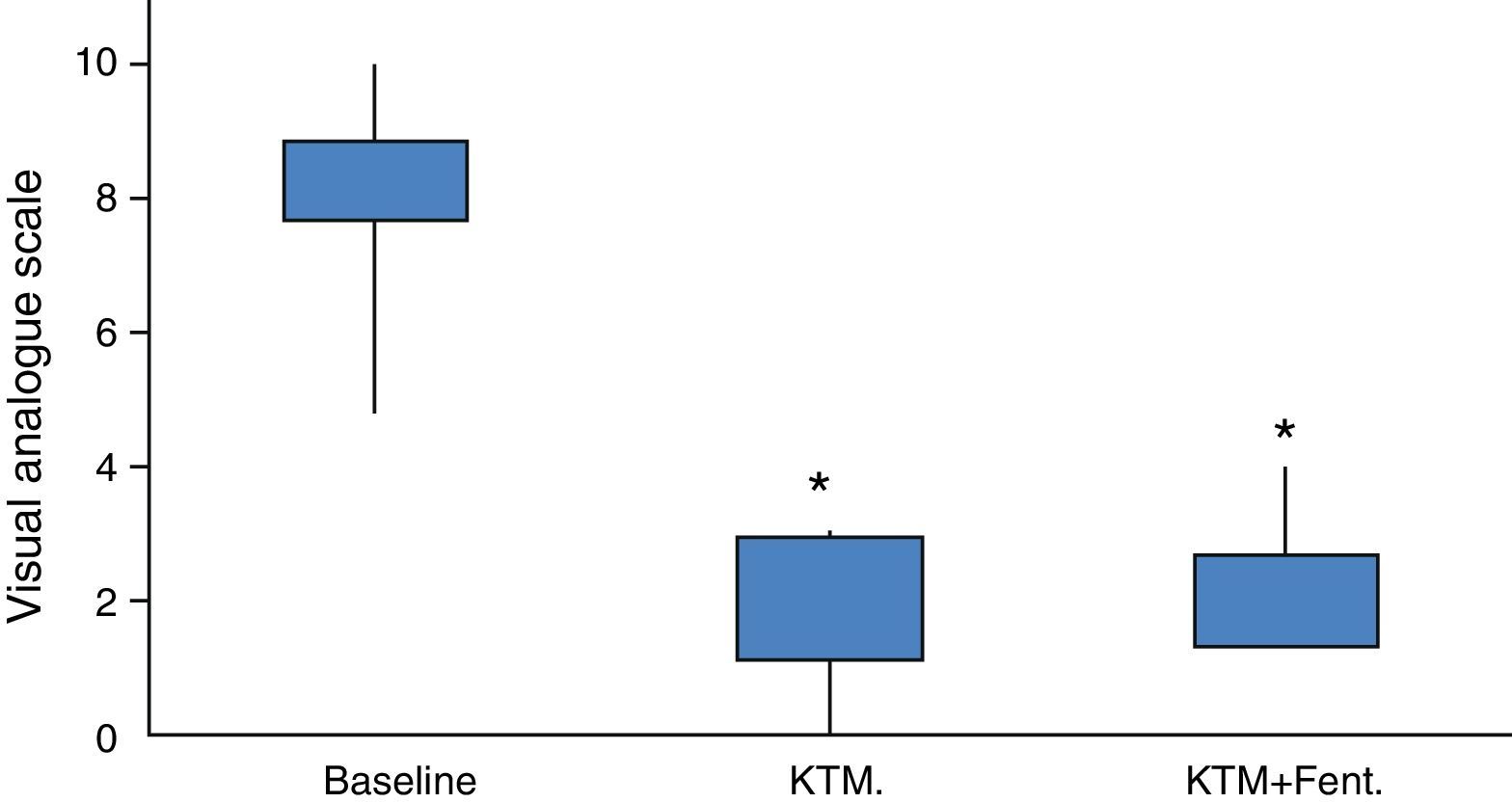

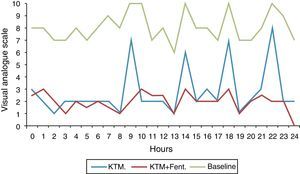

The success rate of KTM mouthwashes was 50% (8/16 patients). The KTM+FENT combination obtained a success rate of 94.1% (15/16 patients). With both treatments, the start time of the analgesic effect was lower than 10min. The main cause of KTM mouthwash failure was the onset of BCP episodes. The KTM+FENT combination reduced the predictable BCP percentage from 75 to 12.5% (p=0.016).

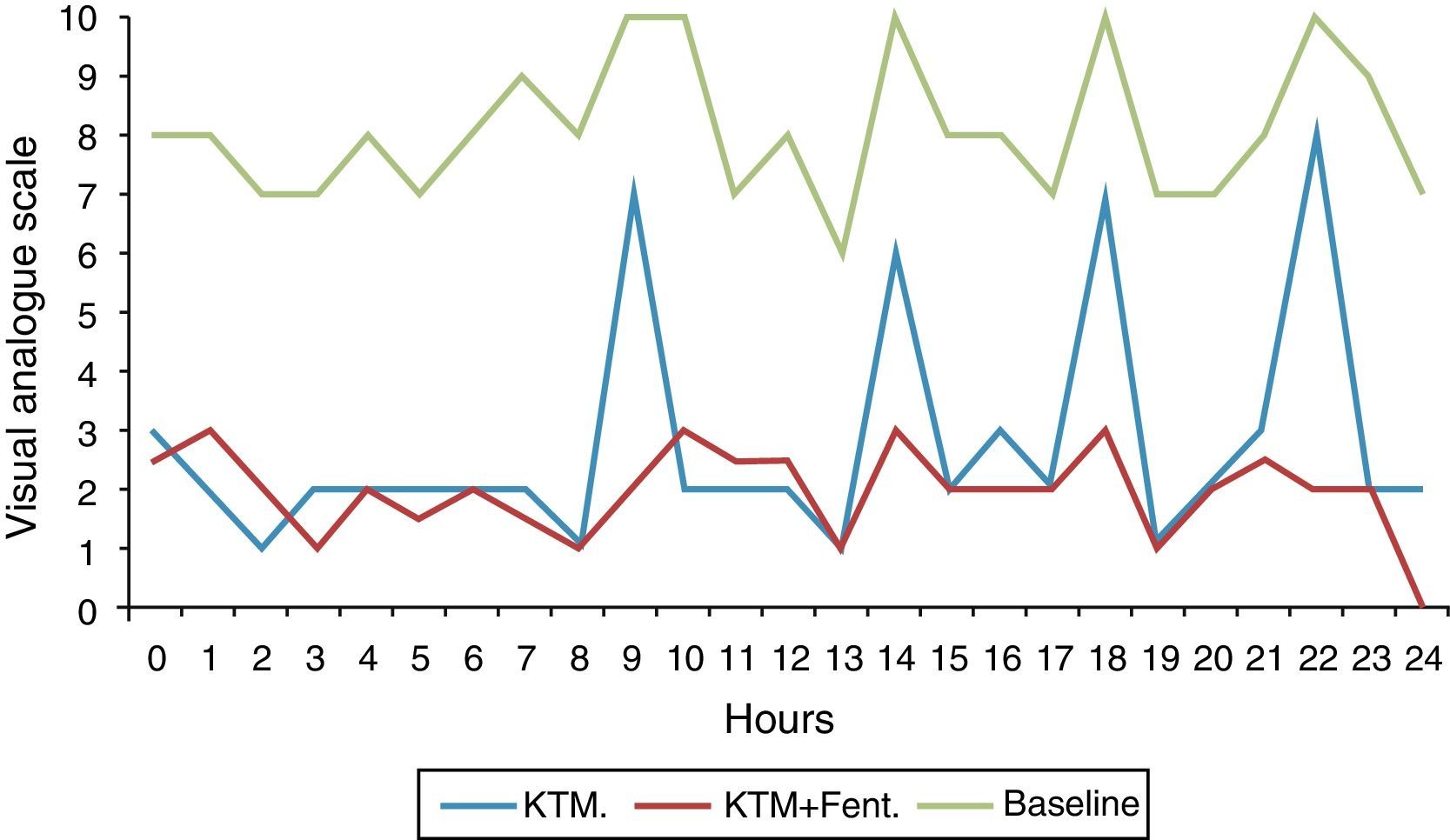

Fig. 2 shows variations in pain during 24h and mean pain prior to the beginning of the analgesic treatment. Fig. 3 shows the mean variation with standard deviation of the treatment with KTM mouthwashes compared to the combination of KTM+FENT mouthwashes in cases of predictable BCP (p<0.001).

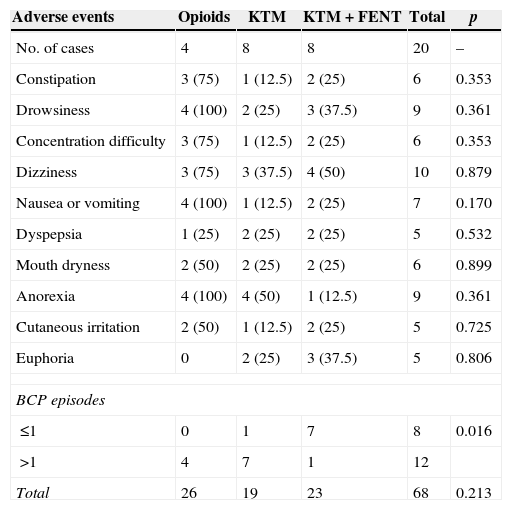

In most cases, adverse events were mild. Drowsiness, dizziness, emesis symptoms and constipation were the most common adverse events (Table 3). Patients considered respondent to treatments based on systemic opioids presented a greater number of adverse events and a progressive increase in doses, but no statistically significant differences. Thus, the number of adverse events per patient was 6.5; 2.3 and 2.8 in the group of patients treated with opioids, KTM mouthwashes and KTM+FENT mouthwashes, respectively. In patients treated with KTM and KTM+FENT mouthwashes, the most common side effect was mild and temporary dizziness.

Adverse events of the different treatment options.

| Adverse events | Opioids | KTM | KTM+FENT | Total | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | 4 | 8 | 8 | 20 | – |

| Constipation | 3 (75) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (25) | 6 | 0.353 |

| Drowsiness | 4 (100) | 2 (25) | 3 (37.5) | 9 | 0.361 |

| Concentration difficulty | 3 (75) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (25) | 6 | 0.353 |

| Dizziness | 3 (75) | 3 (37.5) | 4 (50) | 10 | 0.879 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 4 (100) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (25) | 7 | 0.170 |

| Dyspepsia | 1 (25) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) | 5 | 0.532 |

| Mouth dryness | 2 (50) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) | 6 | 0.899 |

| Anorexia | 4 (100) | 4 (50) | 1 (12.5) | 9 | 0.361 |

| Cutaneous irritation | 2 (50) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (25) | 5 | 0.725 |

| Euphoria | 0 | 2 (25) | 3 (37.5) | 5 | 0.806 |

| BCP episodes | |||||

| ≤1 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 0.016 |

| >1 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 12 | |

| Total | 26 | 19 | 23 | 68 | 0.213 |

One patient may present more than one adverse event. Data expressed in number of cases and percentage. All adverse events which occurred during the follow-up period are recorded.

Used statistical analysis: chi-square test (Chi2) with Yates correction or Fischer's test.

BCP: breakthrough cancer pain (not recorded as adverse events).

The main finding of this study is that KTM mouthwashes have a very rapid analgesic effect and are highly effective for the control of oral cavity pain in cancer patients and in mucositis cases, thus reducing pain at rest and during activities, such as eating, sneezing or yawning. It is possible to speculate that, in certain patients and under certain circumstances, this would be a treatment option for patients with orofacial pain resistant to several treatments, without it being associated with significant adverse events. The agreed use of KTM mouthwashes during several months led to a rapid decrease in symptoms, a significant improvement in quality of life, a high level of satisfaction and a reduction in the use of opioid analgesics and several neuromodulator drugs.

In our series, KTM mouthwashes act as an excellent baseline analgesic with good tolerance. Its main disadvantage is that, in a significant percentage of patients (50% of the cases), it does not control BCP episodes. This BCP represents a significant clinical problem which may have a huge impact on patients’ quality of life because it alters the sleep-wakefulness cycle, sleep, emotional health, personal relations and several daily activities.16 In our cases, these orofacial pains were per se a severe and debilitating disease, as they were commonly associated with fear to swallow, followed by weight loss, malnutrition and immunomodulation alteration. Thus, in our series of cases, the administration of KTM+FENT was associated with an excellent control of BCP episodes. Our observations match a series of epidemiological studies which indicate that this type of drugs could be the most adequate strategy for the treatment of predictable BCP episodes.4,17 Fentanyl is the only active substance in ROO, and its main indication is predictable or unpredictable cancer pain episodes below 30–60min of duration.

These last treatment options led to a significant reduction in the mean doses of maintenance anti-inflammatory agents and opioids with a possible decrease in side effects, such as digestive haemorrhage, renal dysfunction, epigastric distress, vomiting, constipation and with considerable economic savings. The cost of the 100ml bottle of KTM mouthwash is below €15, while the estimated cost of a monthly latest opioid treatment with oxycodone-naloxone and tapentadol is widely above €200. On the other hand, patients showed a high level of satisfaction when using a therapy that controlled pain in 4–5min.

The action mechanism of the KTM mouthwash analgesic effect is not well-known. It could be associated with transmucosal absorption of ketamine or the involuntary swallowing of mouthwash. Clements et al. determine that ketamine plasma levels necessary to obtain an analgesic action after intravenous bolus are approximately 100ng/ml.18 Analgesic effects after its oral administration are below 40ng/ml, presumably due to high levels of norketamine (160ng/ml). We did not measure plasma levels of ketamine, but the Canbay study,19 after the administration of 40mg of mouthwash, detected maximum concentrations of ketamine and norketamine in 16.16 and 11.43ng/ml, respectively. These low levels suggest that it is highly unlikely that systemic absorption played an important role in the reduction of pain and, therefore, a topical effect per se is possible.

A correlation between the analgesic effect and NMDA complex seems more likely. Glutamatergic routes are widely involved in excitatory neurotransmission, including nociception. Glutamate receptor groups are found in the central nervous system and in the nervous fibres of peripheral tissue20,21 and, therefore, the peripheral blockage of receptors may be a promising option. It is not possible to rule out that the analgesic effect and nervous blockage, such as local anaesthetics, of these sub-anaesthetic doses are due to their activity on several opioid receptors, monoaminergics, muscarinics and calcium and sodium ionic channels.22 The clinical use of KTM is limited due to its psychotomimetic and cardiovascular adverse events, such as high blood pressure and tachycardia, though their incidences are materially reduced when administered in low doses. In our series, the use of KTM mouthwashes was not associated with haemodynamic effects, but with mild and temporary psychotomimetic effects during initial uses of the mouthwash. We have not observed gastric, vesical, renal or hepatic effects due to its chronic use.

Our results match those obtained in published studies assessing the use of ketamine mouthwashes, and they show a high rate of effectiveness in several cases of orofacial pain. The group of Ryan et al.23 presents a retrospective study conducted in 8 patients with ketamine mouthwash for the treatment of refractory pain due to oral mucositis, with a 62% success rate. Slatkin et al.24 describe the successful use of oral topical KTM for the treatment of oral mucositis pain in a female patient with tongue carcinoma subject to radiotherapeutic treatment. Other studies show similar results.25

The adequate KTM mouthwash dosage is unknown. In the cases that we presented, the initially used dose is 40mg in each mouthwash, similar to that used in previously mentioned studies (20 or 40mg per mouthwash). In our series, the KTM+FENT combination for several daily activities, mainly chewing, led to a better control of pain in a subgroup of patients with oral intake improvement. We have not currently started to reduce the dose in order to determine the minimum efficient dose. However, since the doses mentioned in this study are considered effective and present no side effects, it was decided to maintain these regimes. In future studies, it should be established if pain relief is dose-dependent, optimum doses should be determined and it should be understood how important the matrix is for its administration and if this could interfere with its topical effect. We used a dilution in Ora-Sweet® syrup which contains 70% sucrose, 6% glycerine and 5% sorbitol, while other authors have used a solution consisting of artificial saliva and physiological saline serum.

ConclusionThe KTM mouthwash used for the treatment of orofacial pain secondary to cancer is an effective, low cost therapeutic option with few side effects. In cases where there are incidental BCP episodes, the KTM+FENT combination is a more advisable therapy. More studies are needed to verify these results and to titre the optimum dose since not enough bibliography on this therapy has been published.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestThe undersigned authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Cortiñas Saenz M, Espín Galvez F, Alférez García I, Menoyo Alonso MB, Vega Salvador A, García-Carricondo A, et al. Tratamiento con enjuagues de ketamina asociado o no a fentanilo transmucoso en el dolor oncológico orofacial resistente a opiáceos mayores. Rev Esp Cir Oral Maxilofac. 2015;37:80–86.