When a patient has multiple injuries, involving serious fractures in the maxillofacial region and base of skull, a tracheostomy is often performed to approach the different affected facial thirds simultaneously. Submental intubation offers an alternative to this type of airway management, involving a decreased risk for the patient due to its safety and versatility in treating nasal fractures and re-establishment of dental occlusion.

MaterialsA total of 30 patients with different degrees of involvement of the facial thirds (superior, middle and inferior) were treated by our team, performing a submental intubation to maintain the airway. These fractures affected nasal bones and dental occlusion.

ResultsIn all cases we accomplished an adequate reduction of nasal fractures and obtained an accurate dental occlusion, with no incidents during or after this intubation.

ConclusionsSubmental intubation is a good alternative to treat multiple injury patients who have nasal and oral cavities involvement, avoiding the use of tracheostomy in cases that do not need it.

Cuando un paciente se encuentra politraumatizado, involucrando fracturas serias en la región maxilofacial, así como en la base del cráneo, se opta por realizar una traqueostomía con el fin de permitir un abordaje simultáneo para los diferentes tercios faciales afectados. La intubación submental ofrece una alternativa a dicho manejo de la vía aérea, significando menor riesgo para el paciente por su seguridad y versatilidad en el manejo de las fracturas nasales y el establecimiento de la oclusión.

MaterialesUn total de 30 pacientes con diferente afección de los tercios faciales (superior, medio e inferior) fueron tratados por nuestro equipo, llevando a cabo una intubación submental para mantener la vía aérea. Las fracturas afectaban los huesos nasales y la oclusión dentaria.

ResultadosEn todos los casos se logró una adecuada reducción de las fracturas nasales y obtención de la oclusión dental correcta, sin presentar eventualidades durante o después de la intubación mencionada.

ConclusionesLa intubación submental es una buena alternativa para poder tratar adecuadamente a los pacientes politraumatizados con afección de la cavidad nasal y oral sin tener que realizar una traqueostomía en casos que no la requieran.

In polytraumatised patients with affected maxillofacial region (with nasal cavity affected and dental occlusion), it is necessary to properly establish an airway and, at the same time, a surgical field that allows for an approach to adequately reduce fractures. To achieve this, there are several techniques, including nasotracheal and orotracheal intubation, both aimed at resolving the airway management problem; however, these techniques do not allow for an adequate handling of the fractured bones in the cavity where the tracheal cannula is introduced (bones from the nose itself in the first case and dental occlusion in the second case).1,2

Given that, in some patients, there are skull base fractures, it becomes particularly dangerous to perform a nasal intubation due to the possible encephalic condition. Thus, oral intubation becomes the other viable option; however, in cases where dental occlusion is compromised, this technique will be implemented using an adequate approach and correctly reducing associated fractures. As a result, it is necessary to perform a tracheostomy to have access to both cavities, but this approach is more traumatic for the patient due to its associated risks.3,4

To solve this situation, Hernández Altemir proposed, in 1986, to manage said patients using orotracheal intubation that surgically turned into submental intubation which involved approaching the floor of the mouth in order to have access to the nasal cavity upon re-establishing dental occlusion without affecting the airway management. This option involves passing the ventilation cannula through a surgically created tunnel, with minimum morbidity for the patient and a low risk of injury to major anatomical structures.5

Description of the submental intubation techniqueThe current technique used by our service for submental intubation was described by Hernández Altemir3 with a modification in the reversion and extubation technique.

Materials- -

Flexometallic tube with a bulb or cuff and a detachable connector.

- -

Curved haemostatic pinches.

- -

Sheet no. 15 with the corresponding handle for it.

- -

4–0 silk or nylon suture.

- 1.

A standard oroendotracheal intubation was performed after asepsis and antisepsis of the mouth and chin (Fig. 1).

- 2.

Subsequently, a 2cm skin incision was made in the paramedian submental region, adjacent to the lower edge of the mandible (Fig. 2).

- 3.

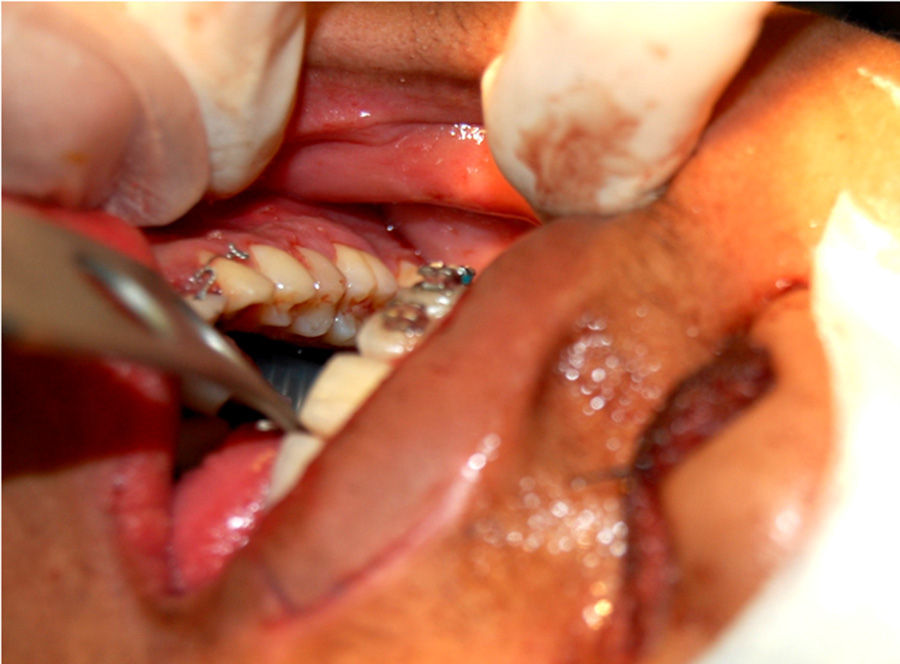

The muscle layers (neck cutaneous muscles and mylohyoid muscles) are removed using a pair of curved haemostatic pinches always in touch with the lingual cortex of the mandible. On the lingual floor mucosa, an intraoral incision will be made using the distal end of the pinches as a reference, and the pinches will be then opened using the sublingual caruncle as a reference and, as a consequence, a tunnel will be created (Fig. 3).

- 4.

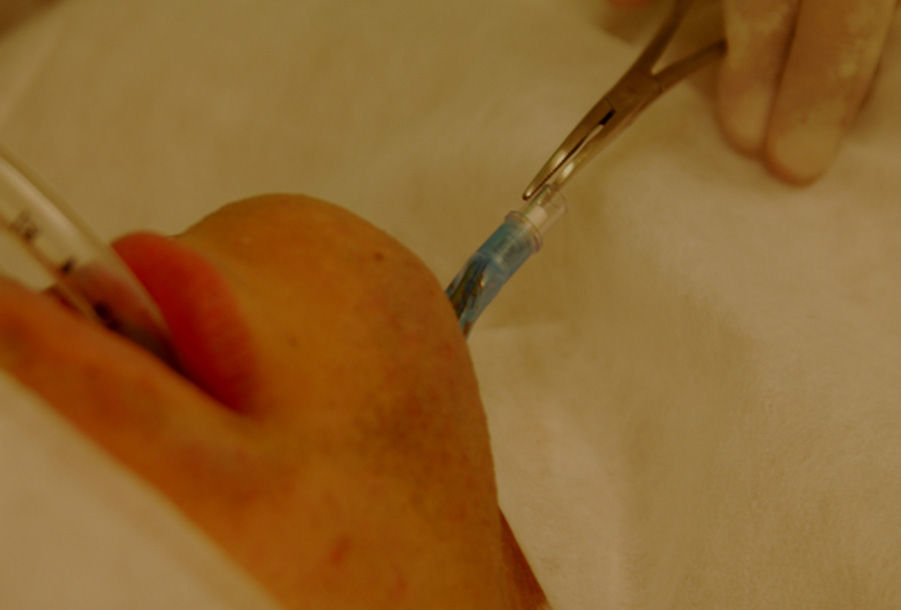

The tube was passed in 2 steps: the tube cuff was first introduced into the mouth and then it was passed through the tunnel using a clamp. The same manoeuvre was then carried out with the proximal end of the tube after disconnecting it from the breathing system of the anaesthesia machine (Figs. 4 and 5).

- 5.

Then, the tube is re-connected to the breathing system of the anaesthesia machine. The tube is placed on the skin in the submental region (Fig. 6).

At the end of the surgery, the reversion is performed by replacing the tube and, subsequently, the cuff through the incision made; the tube is re-connected to the anaesthesia machine, and the intubation becomes a classic oral intubation (Fig. 7).

MethodologyA retrospective, clinical, analytical investigation was conducted by collecting the medical records of all the patients who underwent the submental intubation procedure (30 patients) with trauma to the maxillofacial region from the Santa Paula Hospital, Sao Paulo, Brazil, from April 2009 to May 2013.

Data related to the type of fractures present in each case, sex, age, type of trauma, time required for the submental intubation procedure and the complications associated to it were considered analysis variables in this study.

All the cases mentioned in this paper were treated using this technique, and the mentioned information was tabulated and analysed using the Excel 2007 software.

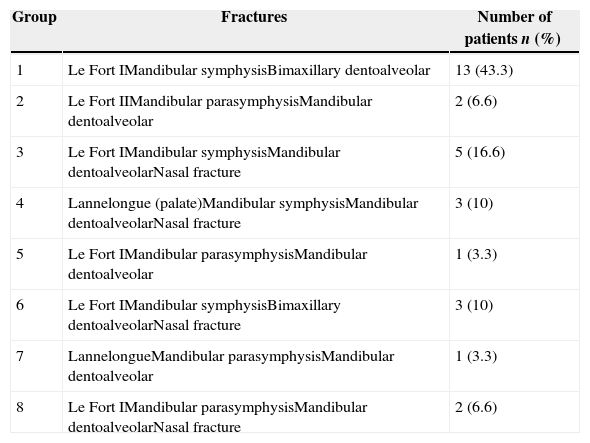

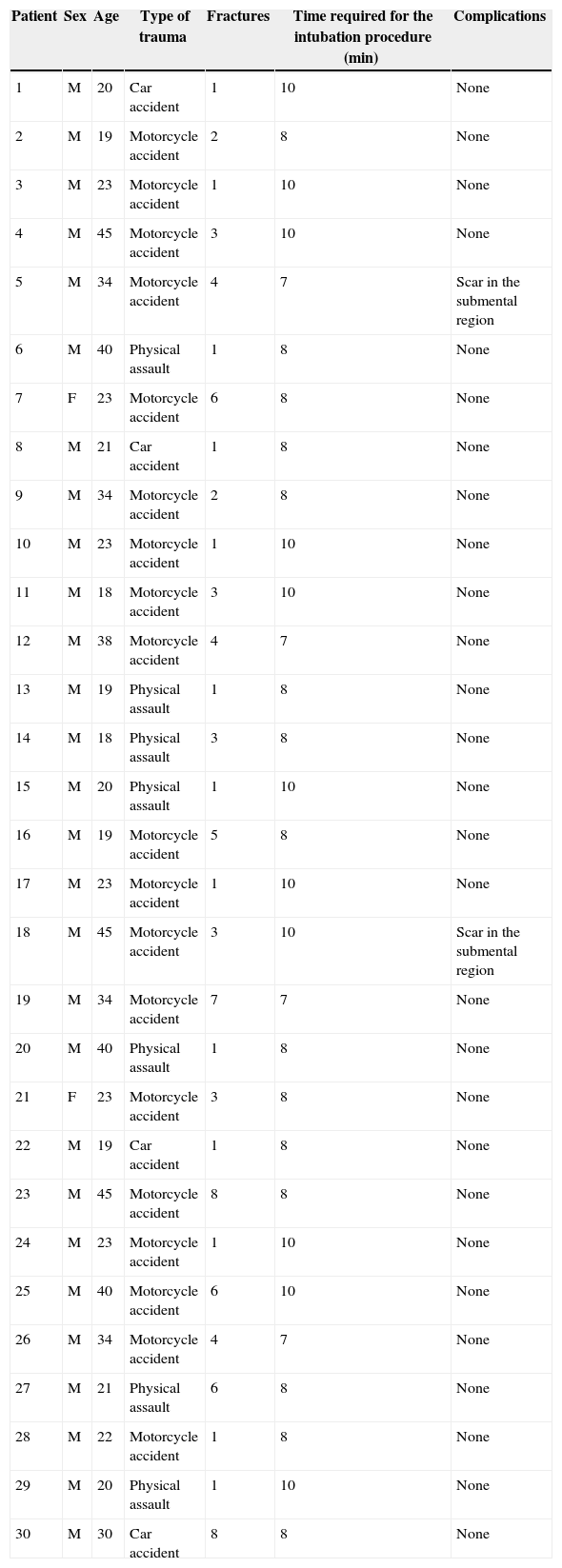

ResultsIn our study, we analysed the cases of 30 patients that presented different types of associated fractures, which were classified into groups from 1 to 6 based on the fractures diagnosed in each case (Table 1).

Classification of fractures in assessed patients.

| Group | Fractures | Number of patients n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Le Fort IMandibular symphysisBimaxillary dentoalveolar | 13 (43.3) |

| 2 | Le Fort IIMandibular parasymphysisMandibular dentoalveolar | 2 (6.6) |

| 3 | Le Fort IMandibular symphysisMandibular dentoalveolarNasal fracture | 5 (16.6) |

| 4 | Lannelongue (palate)Mandibular symphysisMandibular dentoalveolarNasal fracture | 3 (10) |

| 5 | Le Fort IMandibular parasymphysisMandibular dentoalveolar | 1 (3.3) |

| 6 | Le Fort IMandibular symphysisBimaxillary dentoalveolarNasal fracture | 3 (10) |

| 7 | LannelongueMandibular parasymphysisMandibular dentoalveolar | 1 (3.3) |

| 8 | Le Fort IMandibular parasymphysisMandibular dentoalveolarNasal fracture | 2 (6.6) |

Out of the assessed patients, 28 (93.3) were male patients and 2 (6.6) were female patients. Ages ranged from 18 to 45 years, and the cause of facial fractures included road accidents (car) in 4 patients (13.3), motorcycle accidents in 19 patients (63.3) and physical assault (battery) in 7 patients (23.3). All of them underwent a submental intubation without complications during the procedure. The time required to complete the approach until the re-establishment of the ventilation circuit ranged from 7 to 10min, 7min being required in 4 patients, 8min in 15 patients and 10min in 11 patients. After the procedure, only 2 of them showed considerable scarring in the submental region and they both belonged to the black race. The rest of the patients showed no complications or considerable scars during their postsurgical recovery (Table 2).

Characteristics assessed in the study population.

| Patient | Sex | Age | Type of trauma | Fractures | Time required for the intubation procedure (min) | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 20 | Car accident | 1 | 10 | None |

| 2 | M | 19 | Motorcycle accident | 2 | 8 | None |

| 3 | M | 23 | Motorcycle accident | 1 | 10 | None |

| 4 | M | 45 | Motorcycle accident | 3 | 10 | None |

| 5 | M | 34 | Motorcycle accident | 4 | 7 | Scar in the submental region |

| 6 | M | 40 | Physical assault | 1 | 8 | None |

| 7 | F | 23 | Motorcycle accident | 6 | 8 | None |

| 8 | M | 21 | Car accident | 1 | 8 | None |

| 9 | M | 34 | Motorcycle accident | 2 | 8 | None |

| 10 | M | 23 | Motorcycle accident | 1 | 10 | None |

| 11 | M | 18 | Motorcycle accident | 3 | 10 | None |

| 12 | M | 38 | Motorcycle accident | 4 | 7 | None |

| 13 | M | 19 | Physical assault | 1 | 8 | None |

| 14 | M | 18 | Physical assault | 3 | 8 | None |

| 15 | M | 20 | Physical assault | 1 | 10 | None |

| 16 | M | 19 | Motorcycle accident | 5 | 8 | None |

| 17 | M | 23 | Motorcycle accident | 1 | 10 | None |

| 18 | M | 45 | Motorcycle accident | 3 | 10 | Scar in the submental region |

| 19 | M | 34 | Motorcycle accident | 7 | 7 | None |

| 20 | M | 40 | Physical assault | 1 | 8 | None |

| 21 | F | 23 | Motorcycle accident | 3 | 8 | None |

| 22 | M | 19 | Car accident | 1 | 8 | None |

| 23 | M | 45 | Motorcycle accident | 8 | 8 | None |

| 24 | M | 23 | Motorcycle accident | 1 | 10 | None |

| 25 | M | 40 | Motorcycle accident | 6 | 10 | None |

| 26 | M | 34 | Motorcycle accident | 4 | 7 | None |

| 27 | M | 21 | Physical assault | 6 | 8 | None |

| 28 | M | 22 | Motorcycle accident | 1 | 8 | None |

| 29 | M | 20 | Physical assault | 1 | 10 | None |

| 30 | M | 30 | Car accident | 8 | 8 | None |

The submental intubation makes it possible to have access to the nasal and oral cavities in order to reduce fractures with adequate intermaxillary fixation in polytraumatised patients, if necessary. This technique also avoids the risk of damaging the middle base of the skull if the patient has a fracture there.1–3

The submental approach is aimed at avoiding tracheostomy in patients without indication for it (such as ventilation support during a prolonged period of time, several surgical procedures or severe injuries in the 3 facial thirds). Tracheostomy risks are well documented and include the following: haemorrhage, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, tracheostomy cannula obstruction, tracheitis, cellulite, pulmonary atelectasia, tracheoesophageal fistula, tracheocutaneous fistula, pneumothorax, recurrent laryngeal nerve damage, stomal and respiratory tract infections, tracheal stenosis, tracheal erosions, dysphagia, problems with decanulation, excessive scarring, and careful surgical and perioperative handling requirements.4–7

The submental intubation does not imply a considerable risk for patients or a significant extension of surgical time. In our case, the minimum time was 7min and the maximum time was 10min, similar to the figures reported in the literature.8–10

Regarding the approach used in this service, 2 important aspects are worth mentioning: (1) The incision and blunt dissection are made in the paramedian area, in order to avoid the separation or injury of geniohyoid and genioglossus muscles, which are moved towards the middle area. Upon conducting this manoeuvre, the suture may only be performed on the subcutaneous tissue and skin, which enables the rest of the layers to heal by secondary intention. (2) The dissection is performed on the periosteum and not inside the subperiosteal space, as originally described by Hernández Altemir. This is to avoid excessive periosteal section of bone fragments that may already have compromised vascularity. This is based on the fact that periosteal irrigation will not be affected by the approach. The advantages of these modifications are reported in the literature.1,3,10–15

Some authors prefer to perform a second intubation as follows: to conduct a classic oroendotracheal intubation of patients. Subsequently, the submental approach is implemented by placing a second endotracheal cannula, which will be used to maintain the airway after the first cannula has been withdrawn. However, we believe that this technique is too aggressive for patients, since it involves a second intubation and the risk of having laryngeal spasms during the placement of the second cannula. Besides, it is more aggressive to the pharyngeal and laryngeal mucosa of patients.5

Despite the fact that this technique is a good option for the treatment of patients with multiple fractures in the maxillofacial region, it is not free of complications. The most important complications include damage to the tube bulb, submental injury infection, abscess formation in the floor of the mouth, injury to the submandibular salivary ducts or sublingual glands, mucocele formation, injury to the marginal branch of the facial nerve, injury to facial vessels (in some cases), and keloid or hypertrophic scarring in the submental region. In our case, there were 2 patients who belonged to the black race with subsequent hypertrophic scarring; however, the rest of the patients presented no problems during or after the intubation procedure.5–7

Not all the patients treated in our service presented nasal fractures and, nevertheless, a submental intubation was performed. In the literature, there are reports of multiple cases of elective osteotomies, as is the case of orthognathic surgery, Le Fort III osteotomies or even aesthetic surgery, in order to achieve minimum tracheal cannula interference in the facial region to be worked upon. It was deemed convenient to perform this type of intubation in patients who presented fractures in the middle and lower thirds due to the nasal cavity condition resulting from the tube and to facilitate the handling, so as to reduce and fixate fractured fragments.12

In conclusion, the submental intubation offers an adequate, easy and minimally invasive alternative for polytraumatised patients with affected middle and facial thirds, allowing for an adequate reduction and fixation of fracture segments with no intubation cannula interference in the surgical layer, particularly reducing fractures in the nasal cavity when it is necessary to conduct, at the same time, an intermaxillary fixation to re-establish occlusion in patients.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Leandro LFL, Guevara HAG, Marinho K, Rivero CS, Lopez MAL. Intubación submental: experiencia con 30 casos. Rev Esp Cir Oral Maxilofac. 2015;37:132–137.