The aim of the present descriptive study was to record data on maxillofacial trauma in working adults in a 3 year-period in a reference trauma centre in Chile.

Materials and methodsA descriptive study was conducted on cases of maxillofacial fractures treated in the Maxillofacial Surgery Unit of the Hospital Clínico Mutual de Seguridad, Santiago de Chile, over a 3-year period. Frequency, type and cause of injury, as well as age and gender distribution were analysed.

ResultsThe study population consisted of 283 patients, 259 (91.5%) males and 24 (8.5%) females with a mean age of 40.5 (SD: ±20.5) years. In 499 fracture sites zygomatic fractures were the most prevalent location of the 499 fracture sites, in both males and females (48%), followed by orbital fractures (27.2%), and jaw fractures (21.2%). The most common affected part of the face was isolated mid-facial fractures. Traffic-accident-related fractures were the most common cause (39.2%), with the largest proportion of these involving a car accident.

DiscussionThe results presented are in line with other studies and the analysis of this report provides important data for the design of plans for injury prevention, especially for measures in road traffic.

Recopilar información del traumatismo maxilofacial, específicamente en pacientes adultos, en el periodo de 3 años en un centro chileno de referencia de traumatismos.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó un estudio descriptivo retrospectivo en todos los casos de fracturas faciales que asistieron al Servicio de Cirugía Maxilofacial del Hospital Clínico Mutual de Seguridad C.Ch.C., Santiago de Chile, en el periodo de 3 años (enero de 2009-diciembre de 2011). Fueron analizadas las variables y distribución de género, edad, tipo, frecuencia de cada fractura y causa del traumatismo.

ResultadosLa población estudiada consistió en 283 pacientes, 259 (91,5%) hombres y 24 (8,5%) mujeres con un promedio de edad de 40,5 (SD: ±20,5) años. En 499 sitios de fractura las fracturas cigomáticas fueron la localización más prevalente en ambos géneros (48%), seguidas de las fracturas orbitarias (27,2%) y en tercer lugar las fracturas mandibulares (21,2%). La parte de la cara más afectada fue el tercio medio. Los traumatismos por accidente de tránsito fueron la causa más común (39,2%); la gran mayoría de estos fueron por accidente automovilístico.

DiscusiónLos resultados mostrados en este artículo están en línea con la literatura, y el análisis de este reporte provee importante información para el diseño de planes de prevención de riesgos, especialmente para desarrollar medidas en el área del tránsito.

Maxillofacial fractures are an important cause of morbidity and may lead to both aesthetic and functional consequences. The epidemiology of these injuries varies according to the type, severity and causes depending on the studied population.1,2

Geographic area and socio-economic status of the population can affect the results of the different studies. However, recent studies show that damages in the maxillofacial and skull area are usually inflicted by trauma, specifically accidents caused by motorcycle, assaults and falls.3–7

The accumulation of maxillofacial fractures data in the long term is important, since it allows the development and assessment of preventive measures.7

Unluckily, there are no descriptive studies about patients with facial fractures in the Chilean population. Besides, there is few available information regarding the incidences and causes.8

The aim of this descriptive study is the compilation of information about traumatic facial fractures in adult population within a reference centre of trauma level I.

Materials and methodsA retrospective study was conducted in cases of facial fracture that were treated by the Maxillofacial Surgery Unit of Hospital Clínico Mutual de Seguridad (Security Mutual Clinical Hospital), Santiago de Chile, in a 3-year period (from January 2009 to December 2011).

This information was acquired from the revision of electronic clinical records.

The causes of facial trauma were classified in five categories: falls, traffic accidents (motorcycle, vehicle, bicycle and pedestrian impact), violence, a blow with an object (tool or industrial material) and industrial accident. All the patients with maxillofacial fractures that were treated with open or close reduction were included. Facial fractures were classified in anterior wall of the frontal sinus, zygomatic complex (maxillary-zygomatic complex with or without zygomatic arch), mandibular (symphyseal, parasymphyseal, body, angle, branch, coronoid and condylar), orbital (middle wall, floor and roof), extended fractures like type LeFort I/II/III and pan-facial fracture. Nasal fractures were excluded and pan-facial fractures were considered as one for statistical purposes.

Frequency variations, type and cause of damage, as well as gender and age were analysed. The comparisons were performed through a Chi square test. This was followed by a logistic regression analysis to determine the impact of the five facial trauma causes. The final regression sample included variations such as age, gender and cause of facial trauma.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital.

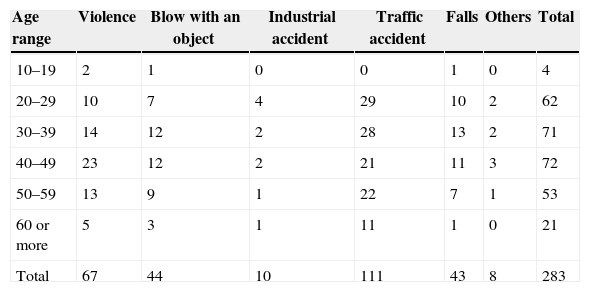

ResultsEpidemiologyThe population consisted of 283 patients, 259 (91.5%) male and 24 female (8.5%) with a mean age of 40.5 years (SD: ±20.5). The youngest patient was 18 years old and the oldest 76. The most affected age range was from 40 to 49 years, followed by the group of 30–39. These two age groups represented half of the patients (Table 1).

Distribution of age and gender of maxillofacial fractures.

| Age range | Violence | Blow with an object | Industrial accident | Traffic accident | Falls | Others | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10–19 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| 20–29 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 29 | 10 | 2 | 62 |

| 30–39 | 14 | 12 | 2 | 28 | 13 | 2 | 71 |

| 40–49 | 23 | 12 | 2 | 21 | 11 | 3 | 72 |

| 50–59 | 13 | 9 | 1 | 22 | 7 | 1 | 53 |

| 60 or more | 5 | 3 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 21 |

| Total | 67 | 44 | 10 | 111 | 43 | 8 | 283 |

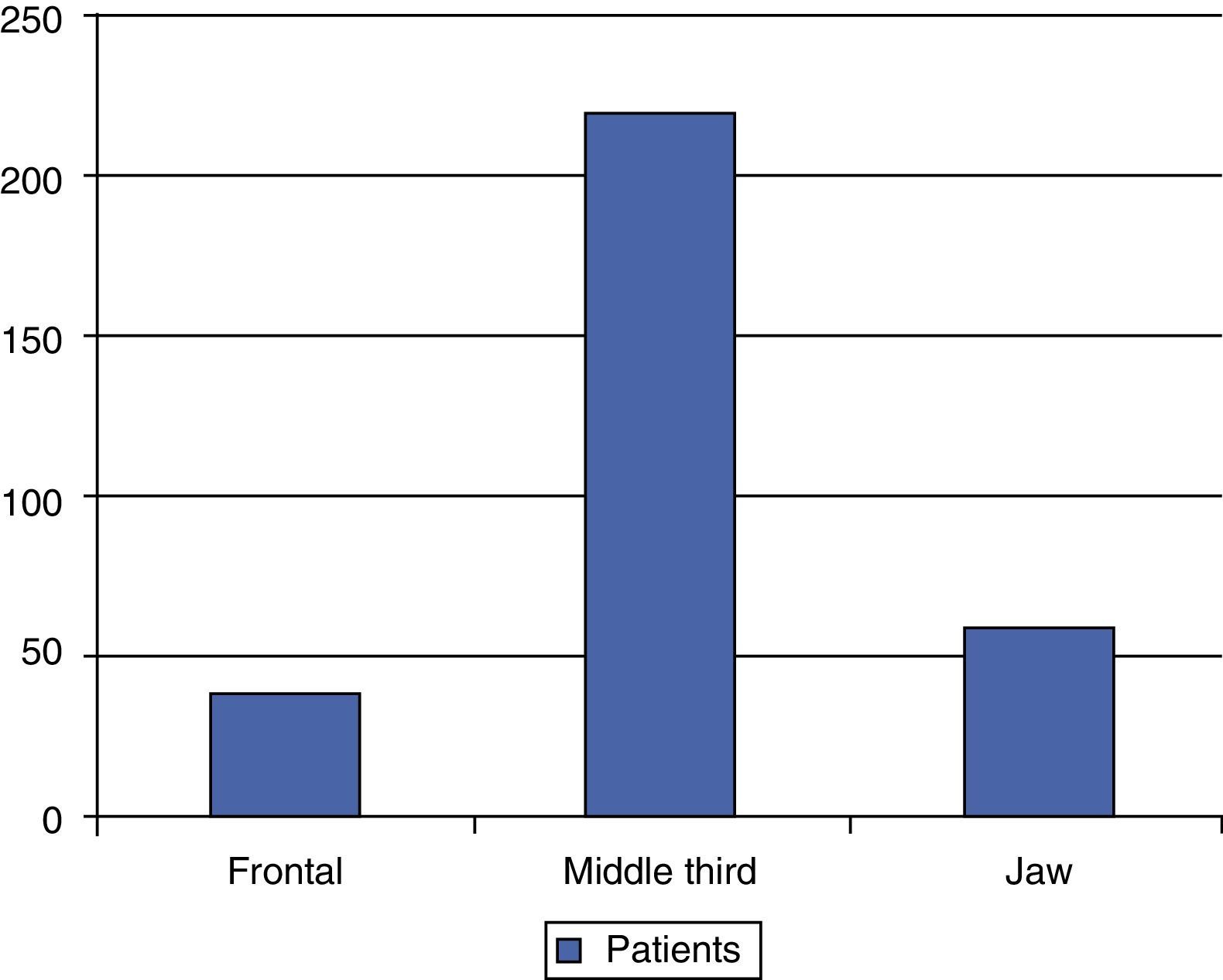

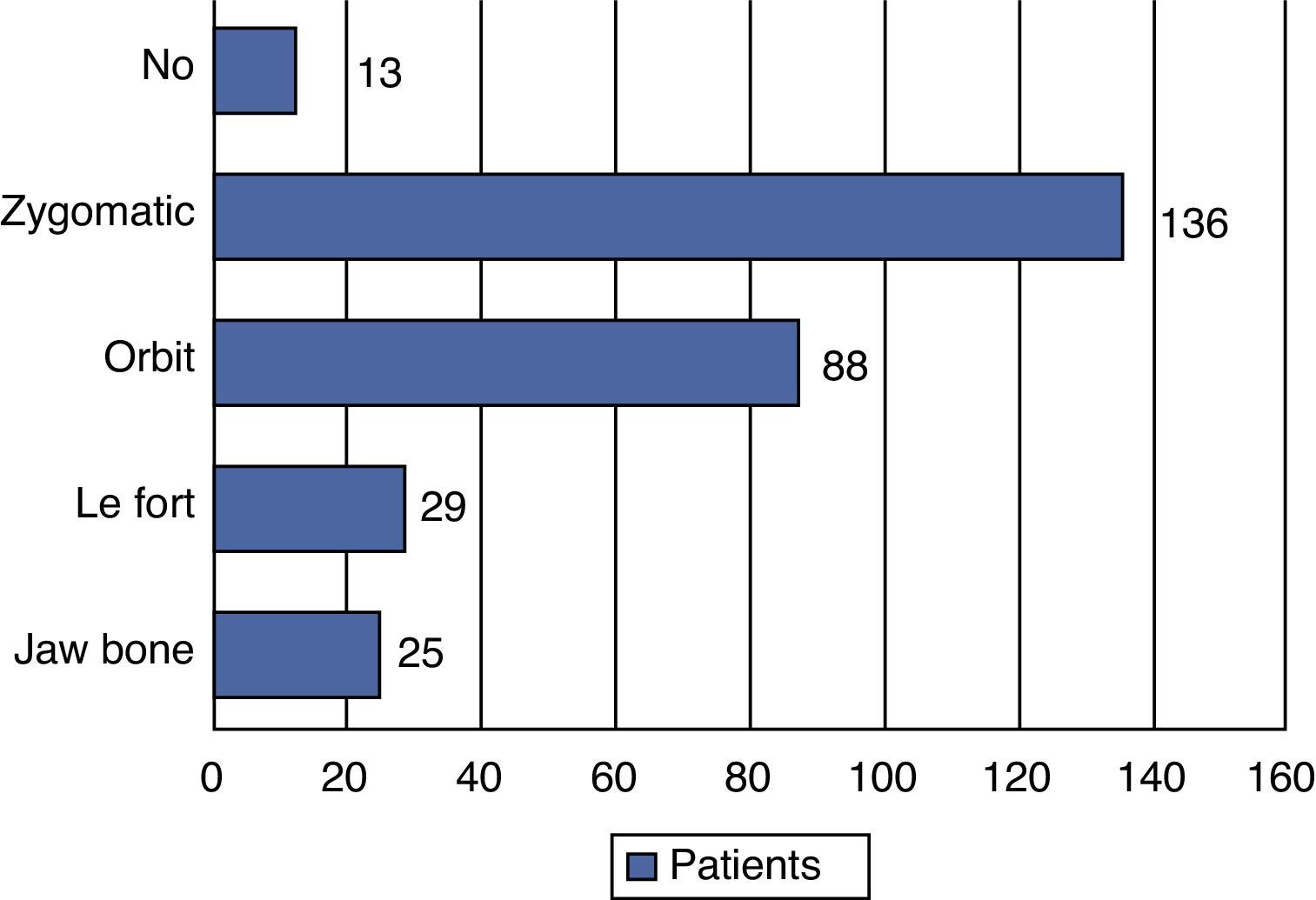

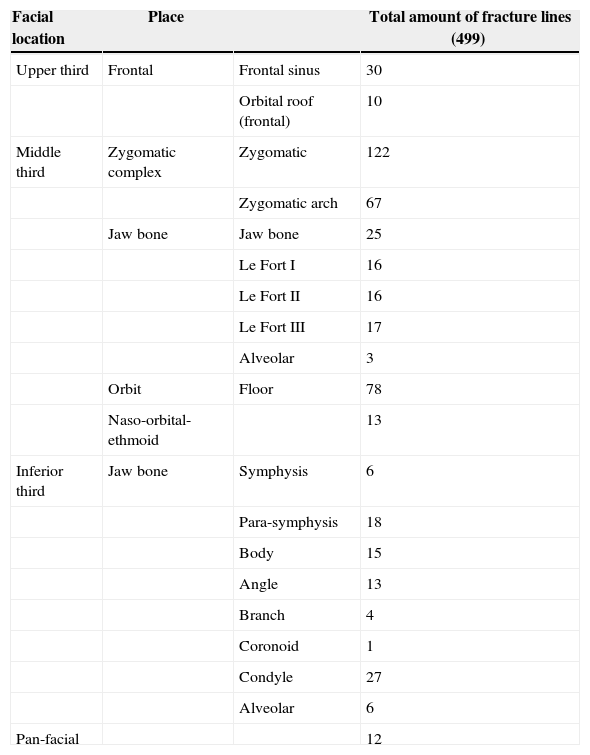

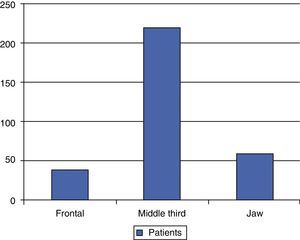

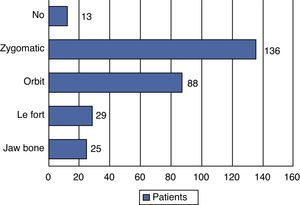

Within a total amount of 499 fracture features, the most frequent location, in both genders, was the zygomatic fracture (136 patients [48%]) followed by orbital fractures (77 patients [27.2%]) and mandibular fractures (60 patients [21.2%]). More details are displayed in Table 2. Half of the patients presented only one fracture, 29.3% presented two fractures and 15% presented three fractured areas. The most affected facial area was the isolated middle third, with 184 patients (65%), and the lower third, with 44 patients (15.5%) (Fig. 1). Fractures that presented comminution were seen in 47 patients (16.6%) and the most frequent association among the location of fractures were zygomatic fractures together with orbital fractures (30 patients [10.6%]). Significant differences were found among the variables of the facial third and the group of patients (p=0.02).

Number of the fracture lines related to the facial location. Nasal fractures were excluded and pan-facial fractures were considered as one.

| Facial location | Place | Total amount of fracture lines (499) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper third | Frontal | Frontal sinus | 30 |

| Orbital roof (frontal) | 10 | ||

| Middle third | Zygomatic complex | Zygomatic | 122 |

| Zygomatic arch | 67 | ||

| Jaw bone | Jaw bone | 25 | |

| Le Fort I | 16 | ||

| Le Fort II | 16 | ||

| Le Fort III | 17 | ||

| Alveolar | 3 | ||

| Orbit | Floor | 78 | |

| Naso-orbital-ethmoid | 13 | ||

| Inferior third | Jaw bone | Symphysis | 6 |

| Para-symphysis | 18 | ||

| Body | 15 | ||

| Angle | 13 | ||

| Branch | 4 | ||

| Coronoid | 1 | ||

| Condyle | 27 | ||

| Alveolar | 6 | ||

| Pan-facial | 12 |

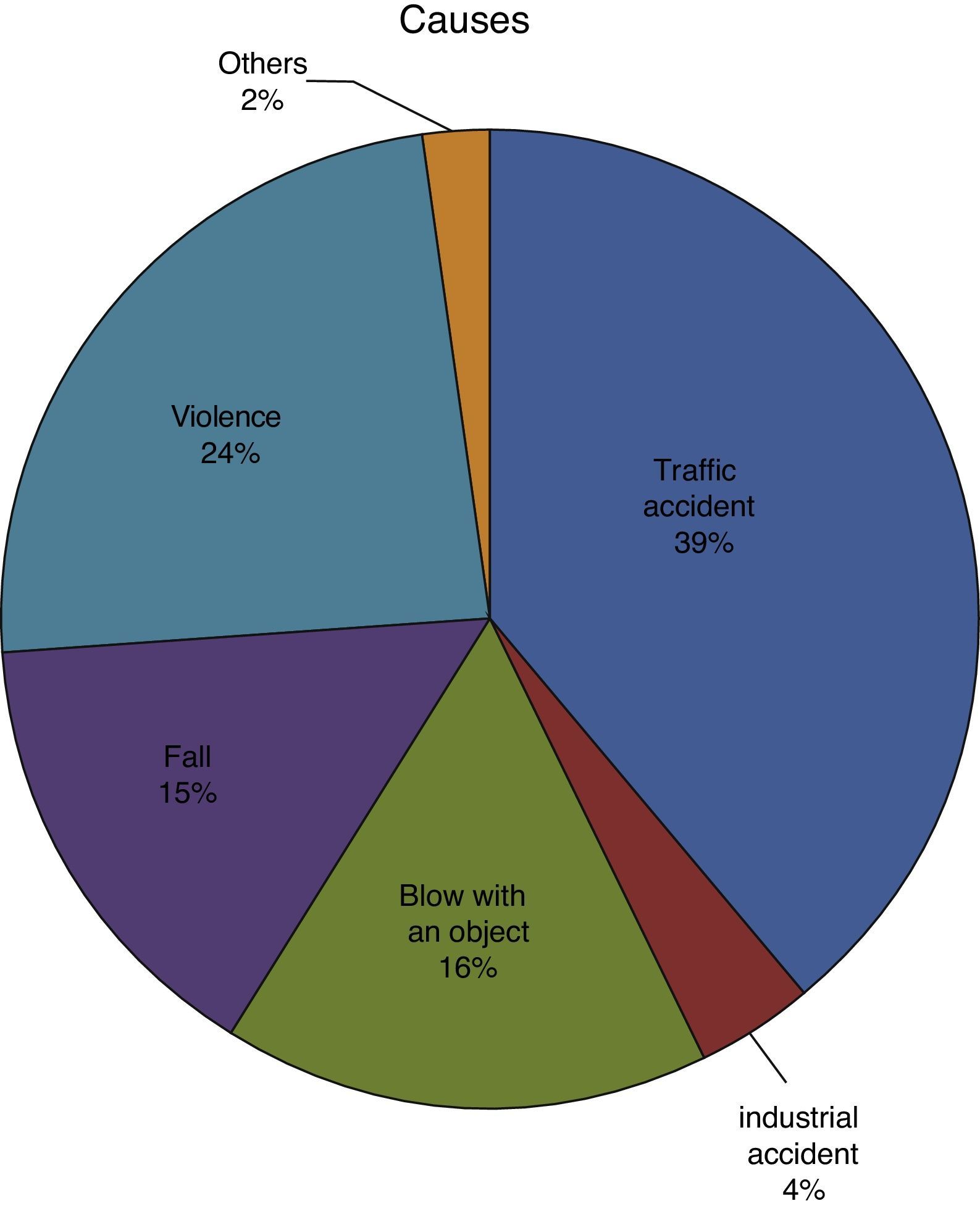

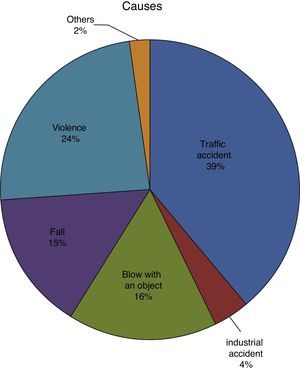

Traumas caused by traffic accidents were seen in 111 patients (39.2%). A great part of this group was due to vehicle accidents (47 patients [16.6%]), followed by the pedestrian impact (25 patients [8.8%]). The second most frequent cause was violent acts (67 patients [23.6%]) followed by blow with an object (44 patients [15.5%]). Table 1 illustrates the causes of trauma according to the patient's age (Fig. 2). The peak in the incidence of vehicles accidents was the age group of 20–29 years old in both genders, which represents half of the causes in this interval. The incidence of violence as a cause was high in the group of 40–49 years old. No significant differences were found among the age ranges and their cause. However, there were statistical differences among the facial thirds and the aetiology (p=0.004).

Mandibular fracturesThere were 60 patients (21.2%) with mandibular fractures (55 related to the middle third), among which 90 fracture lines were counted. Twenty-five patients (8.8%) presented a single fracture feature and 11 (3.8%) presented two features. The two major causes of mandibular fractures were violence or assault, followed by vehicle accidents. The most frequent location was the condyle, followed by the parasymphyseal fractures. The assault and traffic accident led to a greater tendency to present body and parasymphyseal fractures, respectively.

Fractures in the middle third364 fracture features were counted among 220 patients with middle third trauma. In this group, 136 patients presented 189 fractures in the zygomatic complex, 88 orbital fractures, 49 extended LeFort-type fractures, 25 mandible fractures and 13 nasal-orbital-ethmoid fractures (Fig. 3).

Among these, fractures in the zygomatic body were the most common. The main causes of these fractures were violence, falls, and motorcycle accidents. Even more, 60.5% of the falls and 66.7% of the motorcycle accidents resulted in zygomatic fracture. Orbital fractures were in the second place (77 patients), unleashed mainly by violence. The most common compromised area of them was the lower orbital area (88.6%).

The nasal-orbital-ethmoid fractures were present in 13 patients, frequently related in decreasing order to the LeFort-type, pan-facial and zygomatic complex fractures.

Fractures type LeFort I and II were found in 16 each, LeFort III were seen in 17 patients, while 12 patients had a combination of fractures in three-thirds of the face (pan-facial). The most common cause of the extended facial fractures was the traffic accident, specifically those caused by vehicles and pedestrian impact.

Finally, isolated jaw fractures were seen in 25 patients and one related to the nasal-orbital-ethmoid fractures.

Upper third of the faceIn the upper third of the face, 40 patients suffered some type of fracture, 30 of anterior table of frontal sinus and 10 of orbital roof, mainly caused by falls from great high and traffic accidents.

Open or close reductionIn this study, titanium plates and screws were used in an open reduction, except for isolated fractures of zygomatic arch, which were treated with a half-closed reduction through Gillies technique. From the 283 patients, 195 were submitted to a treatment with open reduction. The rest were orthopaedically and/or medically treated. The most common closed treatment was the one of the zygomatic fractures without displacement (42 patients). In second place, orbital fractures without functional compromise (29 patients) with the orbital ground as their most frequent location (71.4%). The third most common location of fractures was the mandibular condyle (18 patients).

DiscussionChile is a country with high rates of work-related accidents, which has made it necessary to collect evidence during the last 30 years in order to implement insurance for workers in case of an eventual traumatic accident related to work. These insurances created centres of trauma to treat complex severe and chronic illnesses caused by work.2 In our country, it is binding that the insurance company (called Mutual) covers the total amount of the working population against consequences related to work-related accidents and the displacement towards this one. The hospital Mutual de Seguridad only insures adult workers, which means that children, students, hose wives, as well as adults older than 65 years old are not foreseen under this law. Nevertheless, the work-related accident law allows an identification of a diverse adult population with a relative high number of cases.

This study describes the epidemiology of 283 patients with facial fractures except for nasal fractures. The male–female ratio was 10:1. The predominance of the male gender in this population of patients is a constant finding in most of the studies. However, this proportion was higher than what was indicated in other countries.9–11 The population in our study tends to be older than in other studies, probably because children under 18 years old are excluded from the average.

The zygomatic complex, the orbit and the maxillofacial fractures were the main locations, amounting to 72% of the fracture locations. Previous studies indicate that the most common cause of facial fractures varies from place to place. With the exception of some studies, the most common cause of this injury is the traffic accident.12 In this regards, it is believed that, generally, the percentage of facial fractures caused by vehicle accidents has decreased. This is due to the preventive education, such as promotional campaigns of seatbelt use in vehicles and the law on restriction of alcohol consumption while driving.13 Other studies have evidenced that assaults are the most frequent cause.14–16 The reason why the acts of violence are the second most common cause of facial fractures in Santiago is distinguished when considering the sociocultural stratum. The matter of violence as a primary cause of facial fracture among other populations has been discussed in various studies with substantial analysis that alcohol is a contributing factor,17 which may be similar in this geographical area.

The results in this report show traffic accident, especially vehicle accident, as the principal cause. This was particularly significant in the group from 20 to 29 years old. Unlike other studies, the group from 40 to 49 years old was the most representative group.18,19 Ironically, the most common cause of this group was the acts of violence. These findings can be compared with several other reports.18–20

With the exception of the mandibular fractures, there is scarce knowledge about the relation between the cause of facial fractures and the location in the middle third. Ellis et al.14 analysed 2067 cases of orbital-zygomatic fractures, showing the front-zygomatic stitch as the most frequently associated with motorcycle accidents. Our study evidences that the fractures of the zygomatic complex were frequently observed among patients injured due to falls. This study also shows that the strength tends to impact in the lateral side of the face when it comes to vehicle accidents. Even more, 60.4% of the falls in this report caused a zygomatic fracture, 22% of these were associated with an orbital component, which suggests an exhaustive orbital examination because of the presence of a zygomatic fracture.

The second most frequent fractures were the orbital fractures, which affected 77 patients with violence as the main factor, followed by vehicle accidents, blows with objects and industrial accidents in equal amount. The epidemiology about this trauma was similar to other studies;21,22 72.3% were treated with an orbital reconstruction titanium mesh.

As regards the lower third or mandibular area, it was found only in 21.2% of the total amount of patients. Previous studies evidence that the jaw and nasal bones are the two most frequent locations of maxillofacial fractures.18,22–24 We excluded nasal fractures because it is a treatment carried out by the otolaryngologists team in our hospital. The possible explanation for the low percentage obtained in this study is unknown. However, it is possible that these fractures prevail when the causes of trauma are violence and falls,15 unlike our study, where traffic accident was predominant.

This analysis reveals the facial fractures’ pattern in the Chilean working population. Nevertheless, this study presents several restrictions. In Santiago, there are three hospitals that insure workers. They constitute the Asociación Chilena de Seguridad (Chilean Security Association). All the hospitals in Chile (public, private and mutual hospitals) treat patients with facial fractures; however, some of them receive more patients than others. Thus, the other two entities are out of this sample. Wok-related accidents are treated by these mutual insurance companies, while the accidents due to alcohol consumption and traumas not related to work are treated in private and public hospitals. Therefore, it is questionable whether the results of our study could be extrapolated to the whole population of Santiago. For this reason, multi-centre studies are necessary.

Besides, like other retrospective studies, this retrospective descriptive study can be subject to biases of information. However, these presented results are in line with other studies. In addition, the analysis of this report brings important information for the design of damage prevention schemes, especially about the measures of the traffic displacement.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Gonzalez E, Pedemonte C, Vargas I, Lazo D, Pérez H, Canales M, et al. Fracturas faciales en un centro de referencia de traumatismos nivel i. Estudio descriptivo. Rev Esp Cir Oral Maxilofac. 2015;37:65–70.