Lupus nephritis (LN) is a consequence of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE). Renal biopsy is a potential prognostic biomarker for renal function.

ObjectiveTo correlate histopathological findings and renal function in children with LN.

Materials and methodsA retrospective observational study was conducted on children with a histopathological diagnosis of NL. Patients with no follow-up registered were excluded. The kidney biopsy at diagnosis was evaluated using the ISN/RPS scale. The Kappa index was used to determine the level of agreement between renal failure (Glomerular Filtration Rate [GFR] < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and presence or absence of each index on the modified ISN/RPS scale.

ResultsA total of 57 patients with NL were treated from 2011 to 2018 at the institution. Of these, 40 (70%) met inclusion criteria, and 10 (25%) were male. The median age of NL diagnosis was 12.9 years (IQR, 11.1–14.9). Follow-up time was 2.3 years (IQR, 1.0–5.16). At diagnosis, karyorrhexis was the characteristic with highest level of agreement with renal failure (k = 0.1873 SE = 0.0759 P = .0068) and at the last follow-up, it was global segmental sclerosis (k = 0.1481 SE = 0.078 P = .0287). There was no difference in the GFR at the last follow-up and the presence of proteinuria at diagnosis (P = .3936).

ConclusionRenal biopsy findings may be an insufficient tool to predict renal function. Treatment and prognosis of patients with NL should be done using other biomarkers and clinical signs. Prospective studies should be performed to confirm this hypothesis.

La nefritis lúpica (NL) es una consecuencia del lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES). La biopsia renal es un potencial biomarcador de pronóstico de función renal.

ObjetivoCorrelacionar hallazgos histopatológicos y la función renal de los pacientes pediátricos con NL.

Materiales y métodosEstudio observacional retrospectivo. Se incluyeron pacientes pediátricos con diagnóstico histopatológico de NL. Se excluyeron pacientes sin seguimiento por la institución. Se evaluó la biopsia renal al diagnóstico con la escala modificada de la ISN/RPS. Se usó el índice Kappa para determinar el nivel de acuerdo entre falla renal (tasa de filtración glomerular [TFG] < 60 mL/min/1,73 m2) y presencia o ausencia de cada índice de la escala modificada de la ISN/RPS.

ResultadosEntre el 2011 y el 2018, 57 pacientes con NL fueron atendidos en la institución, 40 cumplieron criterios de inclusión, 10 (25%) eran de sexo masculino. La mediana de edad de diagnóstico de NL fue 12,9 años (RIC 11,1–14,9). El tiempo de seguimiento fue 2,3 años (RIC 1,0–5,16). Al diagnóstico, la cariorexis fue la característica de la escala con mayor nivel de acuerdo con falla renal (k = 0,1873, EE = 0,0759, P = ,0068) y al último seguimiento lo fue la esclerosis segmentaria global (k = 0,1481, EE = 0,078, P = ,0287). No hubo diferencia en TFG al último seguimiento y presencia de proteinuria al diagnóstico (P = ,3936).

ConclusiónLa biopsia renal puede ser insuficiente para evaluar la predicción de la función renal. El tratamiento de pacientes con NL debe realizarse utilizando otros biomarcadores y signos clínicos. Deben realizarse estudios prospectivos que puedan confirmar esta hipótesis.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic multisystemic autoimmune disease with high morbidity and mortality.1 It has a great variability in its clinical presentation and evolution, which is the result of the interaction of epigenetic, immunological, hormonal and environmental factors.2 The clinical course of this condition is more severe in pediatric patients than in adults. The prevalence of SLE is 70–90 per 100,000 individuals, of whom 20% are diagnosed before the age of 18 years.3 In Colombia, 50%–55% of the adults and 75% of the children with SLE suffer from lupus nephritis (LN) at some point in their evolution.4 In infants, the female/male ratio is 4.5/1.3,5 The mean age of presentation of LN varies between 12 and 17 years in children, being less frequent in those under five years of age.3,6,7 Likewise, LN affects Black, Latino and Asian people more than Caucasian patients.8

The diagnosis of LN represents a challenge for the clinical team. This disease can begin as a clinical picture similar to acute glomerulonephritis, or may be as severe as the rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis with renal failure.9 The five-year renal survival of children with LN has improved markedly in the last decades and it currently ranges between 77% and 93%. However, compared to healthy infants, the mortality rate observed in this population is 19 times higher.10

Taking into account that the clinical symptoms correlate with the patterns of glomerular injury, the renal biopsy (RB) is of great importance in the diagnostic approach of LN and, based on this, it is possible to guide the treatment and establish the prognosis.11,12 In 1982, the World Health Organization (WHO) published the first classification of LN, which was used until 2004. Subsequently, the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS) classification arouse, which enhanced the standardization and reproducibility of the diagnosis to identify the established kidney injury.13 In 2018, Bajema et al. conducted a revision of the ISN/RPS classification in order to reduce conflictive definitions and inter-observer variability.14

Retaking the importance of the RB in the diagnosis of LN, different authors have tried to establish the relationship between the clinical, laboratory and histological findings in the adult and pediatric populations with contradictory results. Dasari et al., in a systematic review that included six studies, concluded that the ISN/RPS classification system and the activity or chronicity indices present a low level of agreement among pathologists, which makes difficult their use in clinical practice.15 On the other hand, Rijnink et al., in a cohort of 105 adult patients with LN, proposed the fibrinoid necrosis, the fibrous crescents and the interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy found in the biopsy as potential biomarkers that allow to assess the risk of progressive renal injury.16 Currently, there is no consensus on the potential use of the RB findings to predict the renal survival in pediatric patients with LN. Therefore, this study seeks to correlate the histopathological findings and the renal function of pediatric patients with LN.

MethodsCali is the capital of the department of Valle del Cauca and is the third most populated city in Colombia. The Fundación Valle de Lili is a reference center in southwestern Colombia, with an approximate coverage of 10 million people. It has a service of pediatric nephrology that cares for 3000 patients per year. This study was conducted following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of the institution (#1396).

Study groups and collection variablesAn observational and retrospective study is presented in this document. All patients with histopathological diagnosis of lupus nephropathy were included. Those who were not followed-up by the institution or without availability of the blocks of renal tissue used for the diagnosis were excluded. The data were obtained from the medical records of the institution.

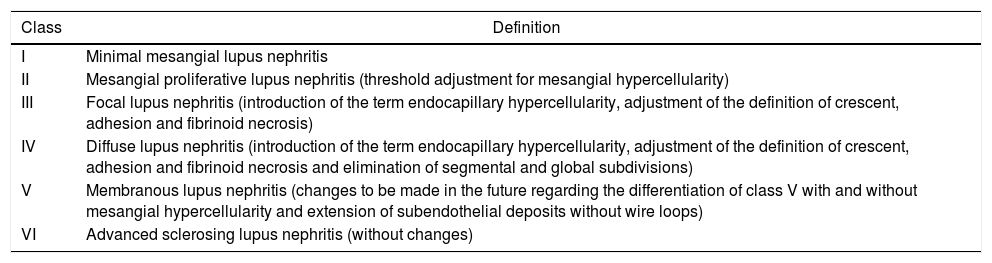

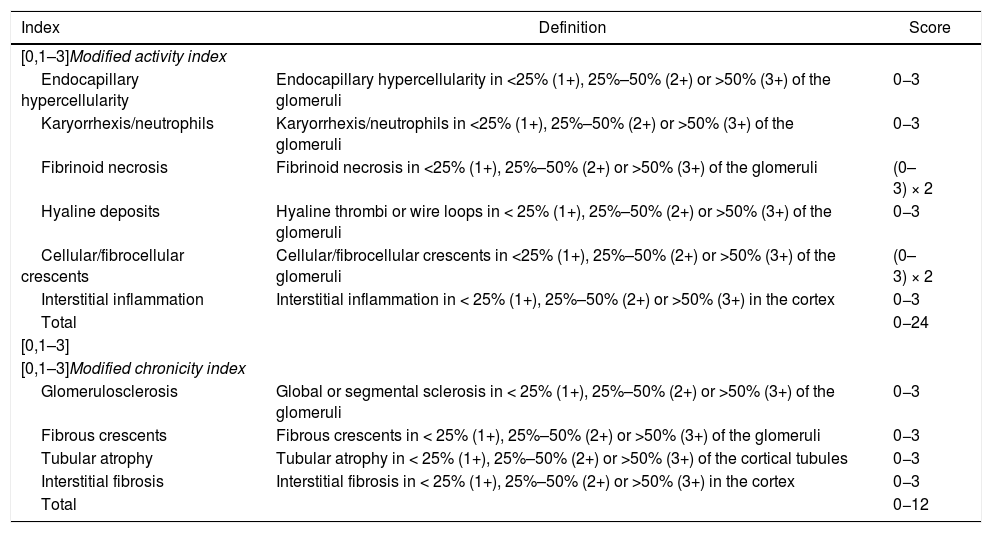

Exposure variablesDemographic variables, clinical characteristics and histopathological results of patients with LN were collected. The blocks obtained in the RB were analyzed by a pathologist, who classified them according to the adjustments made to the classification (ISN/RPS) by Bajema et al. (Tables 1 and 2).14

Classes of lupus nephritis revised by Bajema et al.

| Class | Definition |

|---|---|

| I | Minimal mesangial lupus nephritis |

| II | Mesangial proliferative lupus nephritis (threshold adjustment for mesangial hypercellularity) |

| III | Focal lupus nephritis (introduction of the term endocapillary hypercellularity, adjustment of the definition of crescent, adhesion and fibrinoid necrosis) |

| IV | Diffuse lupus nephritis (introduction of the term endocapillary hypercellularity, adjustment of the definition of crescent, adhesion and fibrinoid necrosis and elimination of segmental and global subdivisions) |

| V | Membranous lupus nephritis (changes to be made in the future regarding the differentiation of class V with and without mesangial hypercellularity and extension of subendothelial deposits without wire loops) |

| VI | Advanced sclerosing lupus nephritis (without changes) |

Adapted from Bajema et al.14

Activity and chronicity indices revised by Bajema et al.

| Index | Definition | Score |

|---|---|---|

| [0,1–3]Modified activity index | ||

| Endocapillary hypercellularity | Endocapillary hypercellularity in <25% (1+), 25%–50% (2+) or >50% (3+) of the glomeruli | 0−3 |

| Karyorrhexis/neutrophils | Karyorrhexis/neutrophils in <25% (1+), 25%–50% (2+) or >50% (3+) of the glomeruli | 0−3 |

| Fibrinoid necrosis | Fibrinoid necrosis in <25% (1+), 25%–50% (2+) or >50% (3+) of the glomeruli | (0–3) × 2 |

| Hyaline deposits | Hyaline thrombi or wire loops in < 25% (1+), 25%–50% (2+) or >50% (3+) of the glomeruli | 0−3 |

| Cellular/fibrocellular crescents | Cellular/fibrocellular crescents in <25% (1+), 25%–50% (2+) or >50% (3+) of the glomeruli | (0–3) × 2 |

| Interstitial inflammation | Interstitial inflammation in < 25% (1+), 25%–50% (2+) or >50% (3+) in the cortex | 0−3 |

| Total | 0−24 | |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Modified chronicity index | ||

| Glomerulosclerosis | Global or segmental sclerosis in < 25% (1+), 25%–50% (2+) or >50% (3+) of the glomeruli | 0−3 |

| Fibrous crescents | Fibrous crescents in < 25% (1+), 25%–50% (2+) or >50% (3+) of the glomeruli | 0−3 |

| Tubular atrophy | Tubular atrophy in < 25% (1+), 25%–50% (2+) or >50% (3+) of the cortical tubules | 0−3 |

| Interstitial fibrosis | Interstitial fibrosis in < 25% (1+), 25%–50% (2+) or >50% (3+) in the cortex | 0−3 |

| Total | 0−12 | |

Adapted from Bajema et al.14

The main outcome variable was the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) at the time of diagnosis and at the last follow-up. The GFR was calculated using the Schwartz formula for people under 18 years of age.17 Once measured, it was categorized according with the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) international classification to assess the renal function of the patient.18 Kidney failure was defined as a GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or kidney failure classified as grade IV or V according to the KDIGO scale.

Arterial hypertension was defined as a systolic or diastolic blood pressure above the 95th percentile for age19 and proteinuria in the nephrotic range (protein-creatinine ratio > 2.0). The need for renal replacement therapy, transplant and death were taken as secondary outcome variables.

Statistical analysisDichotomous variables were reported as percentages. Continuous variables were presented as medians, interquartile ranges or means and standard deviations, according to the normality of their distribution. The kappa coefficient was used to determine the level of agreement between renal failure and the presence or absence of each histopathological characteristic of the ISN/RPS scale, revised by Bajema et al. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine differences in GFR at the last follow-up, according to the presence or absence of proteinuria at diagnosis. The P-value <.05 was considered significant. The analyses were conducted using the Stata® 14.0 statistical package (StataCorp, 2014, College Station TX, USA.).

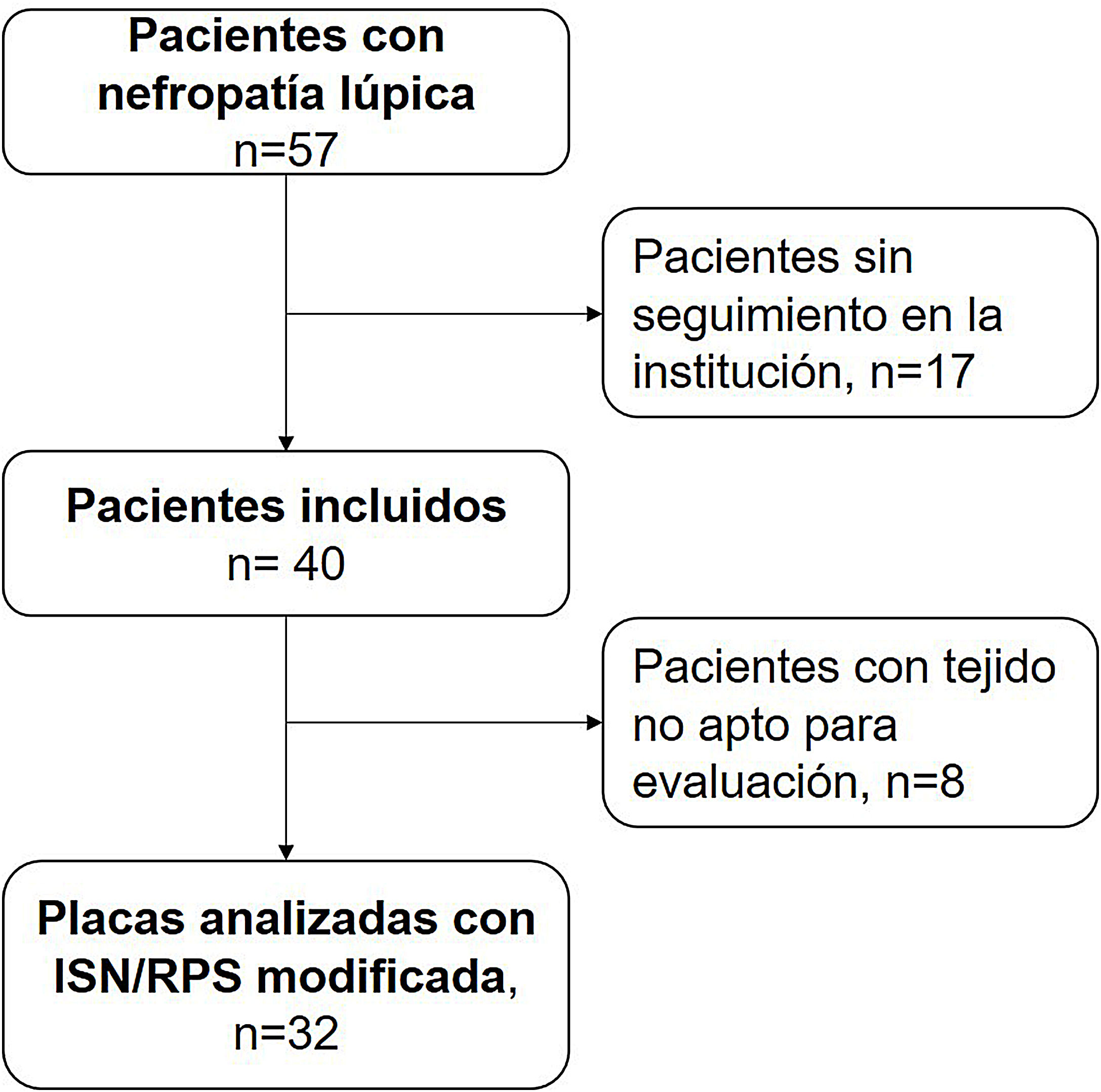

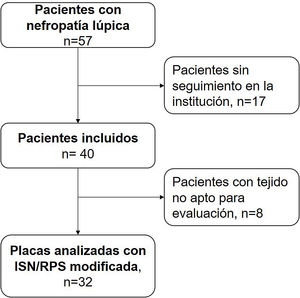

ResultsBetween the years 2011 and 2018, 57 pediatric patients with lupus nephropathy were treated in the institution. Of them, 17 did not have histopathological tissue suitable for reading. The selection of patients is described in Fig. 1.

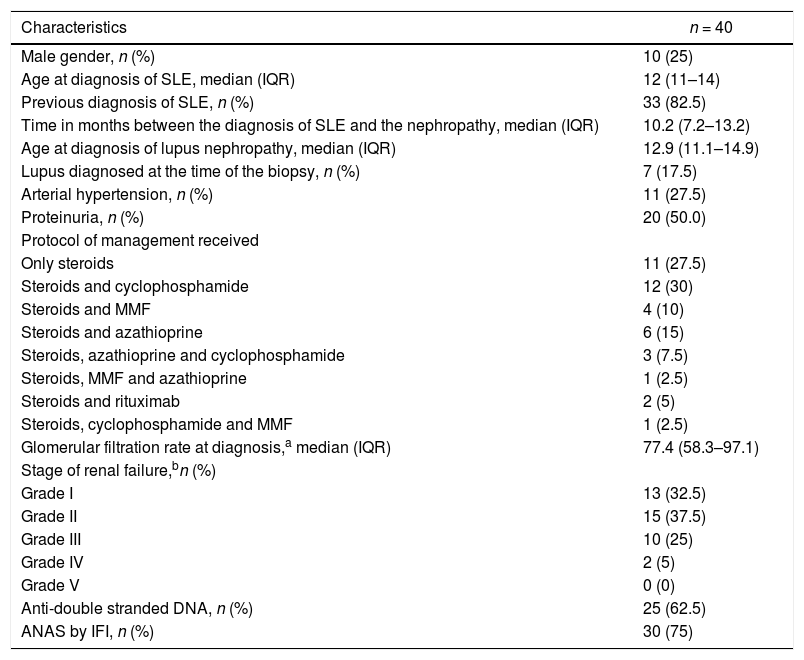

The description of the patients is found in Table 3. Of the 40 patients, 10 (25%) were male, the median age at the diagnosis of SLE was 12 years (IQR 11–14), 7 patients (17.5%) were diagnosed with SLE at the time of the RB. In the 33 patients (82.5%) with previous diagnosis, the time between the diagnosis of SLE and that of LN was 10.2 months (IQR 7.2–13.2). The median GFR at the time of the diagnosis was 77.4 mL/min/1.73 m2 (IQR 58.3–97.1). At the same time, 12 patients (30.0%) had a renal function below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Clinical characteristics of patients with lupus nephritis.

| Characteristics | n = 40 |

|---|---|

| Male gender, n (%) | 10 (25) |

| Age at diagnosis of SLE, median (IQR) | 12 (11–14) |

| Previous diagnosis of SLE, n (%) | 33 (82.5) |

| Time in months between the diagnosis of SLE and the nephropathy, median (IQR) | 10.2 (7.2–13.2) |

| Age at diagnosis of lupus nephropathy, median (IQR) | 12.9 (11.1–14.9) |

| Lupus diagnosed at the time of the biopsy, n (%) | 7 (17.5) |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 11 (27.5) |

| Proteinuria, n (%) | 20 (50.0) |

| Protocol of management received | |

| Only steroids | 11 (27.5) |

| Steroids and cyclophosphamide | 12 (30) |

| Steroids and MMF | 4 (10) |

| Steroids and azathioprine | 6 (15) |

| Steroids, azathioprine and cyclophosphamide | 3 (7.5) |

| Steroids, MMF and azathioprine | 1 (2.5) |

| Steroids and rituximab | 2 (5) |

| Steroids, cyclophosphamide and MMF | 1 (2.5) |

| Glomerular filtration rate at diagnosis,a median (IQR) | 77.4 (58.3–97.1) |

| Stage of renal failure,bn (%) | |

| Grade I | 13 (32.5) |

| Grade II | 15 (37.5) |

| Grade III | 10 (25) |

| Grade IV | 2 (5) |

| Grade V | 0 (0) |

| Anti-double stranded DNA, n (%) | 25 (62.5) |

| ANAS by IFI, n (%) | 30 (75) |

ANAS: antinuclear antibodies; IFI: immunofluorescence; IQR: interquartile range; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; MMF: mycophenolate mofetil.

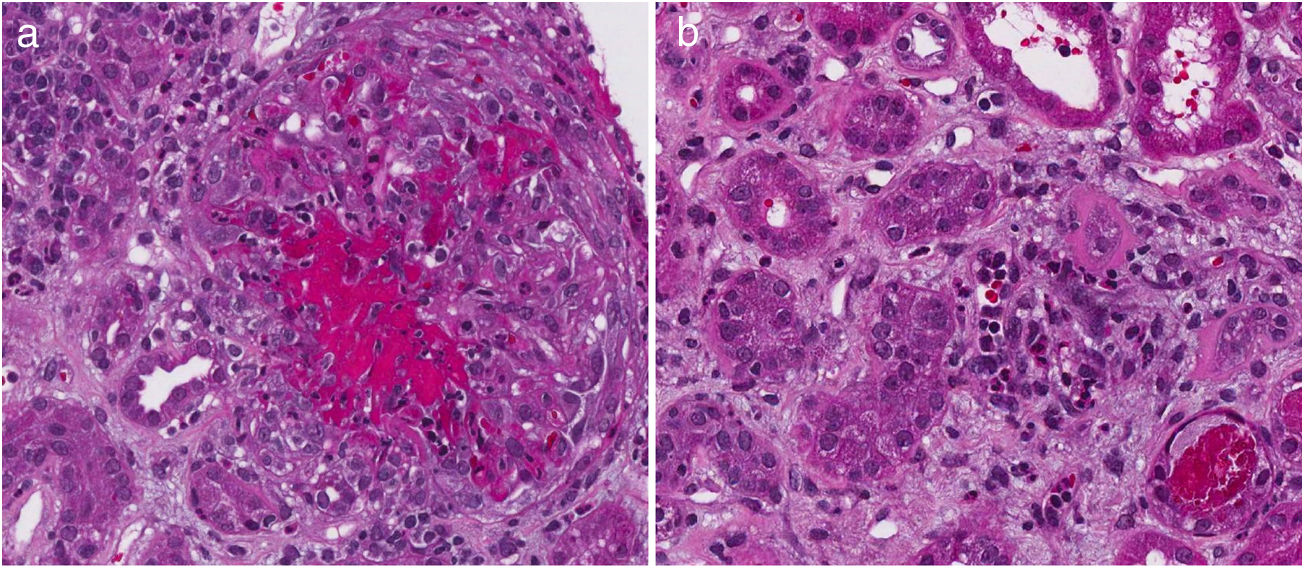

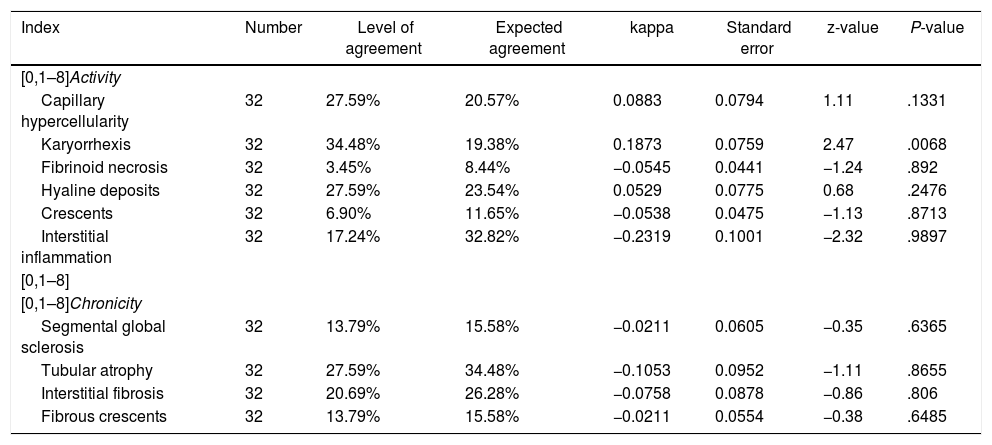

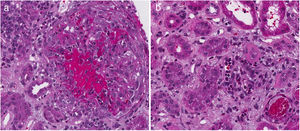

Table 4 describes the level of agreement between the histopathological findings and the GFR at the time of diagnosis. Thirty-two patients had histopathological blocks available and were classified by a pathologist (CJ). Nine of them (28.1%) presented GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. All the characteristics of the adjusted ISN/RPS scale presented low levels according to the renal failure, without statistical significance. In the activity index, karyorrhexis, with 34.48%, was the characteristic with the highest level according to the renal failure. Nevertheless, the kappa coefficient was insignificant (k = 0.1873, SE = 0.0759, P = .0068). In the chronicity index, tubular atrophy presented the highest percentage of agreement (27.59%) with insignificant kappa coefficient (k = −0.1053, SE = 0.0952, P = .8655). Fig. 2 describes the findings of karyorrhexis and tubular atrophy seen in the biopsy.

Level of agreement between the histopathological findings and the glomerular filtration rate at the time of diagnosis.

| Index | Number | Level of agreement | Expected agreement | kappa | Standard error | z-value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1–8]Activity | |||||||

| Capillary hypercellularity | 32 | 27.59% | 20.57% | 0.0883 | 0.0794 | 1.11 | .1331 |

| Karyorrhexis | 32 | 34.48% | 19.38% | 0.1873 | 0.0759 | 2.47 | .0068 |

| Fibrinoid necrosis | 32 | 3.45% | 8.44% | −0.0545 | 0.0441 | −1.24 | .892 |

| Hyaline deposits | 32 | 27.59% | 23.54% | 0.0529 | 0.0775 | 0.68 | .2476 |

| Crescents | 32 | 6.90% | 11.65% | −0.0538 | 0.0475 | −1.13 | .8713 |

| Interstitial inflammation | 32 | 17.24% | 32.82% | −0.2319 | 0.1001 | −2.32 | .9897 |

| [0,1–8] | |||||||

| [0,1–8]Chronicity | |||||||

| Segmental global sclerosis | 32 | 13.79% | 15.58% | −0.0211 | 0.0605 | −0.35 | .6365 |

| Tubular atrophy | 32 | 27.59% | 34.48% | −0.1053 | 0.0952 | −1.11 | .8655 |

| Interstitial fibrosis | 32 | 20.69% | 26.28% | −0.0758 | 0.0878 | −0.86 | .806 |

| Fibrous crescents | 32 | 13.79% | 15.58% | −0.0211 | 0.0554 | −0.38 | .6485 |

Data from the follow-up of the 40 patients were obtained. The median follow-up in them was 2.3 years (1.0–5.16). At the end of the follow-up, six individuals (15.0%) had arterial hypertension and 15 (37.5%) proteinuria. Six patients (15.0%) required renal replacement therapy and one required renal transplantation (15.0%). The median GFR in all cases was 84.4 mL/min/1.73 m2 (67.4–97.0). Of them, 9 individuals (22.5%) had GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. In the last follow-up, there was no difference in GFR between patients with presence and absence of proteinuria at diagnosis (P = .3936).

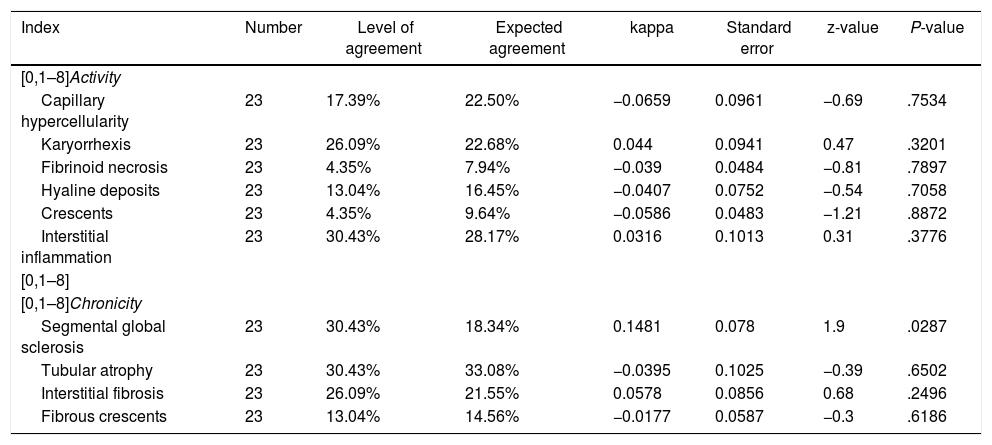

Level of agreement in the last follow-upFor the analysis in the last follow-up, the patients with renal failure at the time of diagnosis were excluded, calculating the levels according to the 23 remaining cases. Table 5 describes the level of agreement between the histopathological findings and the GFR at the last follow-up. In the activity index, karyorrhexis was the characteristic with the highest level of agreement (26.1%), but with insignificant kappa (k = −0.044, SE = 0.0941, P = .3201). In the chronicity index, global segmental sclerosis (k = 0.1481, SE = 0.078, P = .0287) and tubular atrophy (k = −0.0395, SE = 0.1025, P = .6502) were the characteristics with the highest percentage of agreement (30.4% for both variables).

Level of agreement between the histopathological findings and the glomerular filtration rate at the last follow-up.

| Index | Number | Level of agreement | Expected agreement | kappa | Standard error | z-value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1–8]Activity | |||||||

| Capillary hypercellularity | 23 | 17.39% | 22.50% | −0.0659 | 0.0961 | −0.69 | .7534 |

| Karyorrhexis | 23 | 26.09% | 22.68% | 0.044 | 0.0941 | 0.47 | .3201 |

| Fibrinoid necrosis | 23 | 4.35% | 7.94% | −0.039 | 0.0484 | −0.81 | .7897 |

| Hyaline deposits | 23 | 13.04% | 16.45% | −0.0407 | 0.0752 | −0.54 | .7058 |

| Crescents | 23 | 4.35% | 9.64% | −0.0586 | 0.0483 | −1.21 | .8872 |

| Interstitial inflammation | 23 | 30.43% | 28.17% | 0.0316 | 0.1013 | 0.31 | .3776 |

| [0,1–8] | |||||||

| [0,1–8]Chronicity | |||||||

| Segmental global sclerosis | 23 | 30.43% | 18.34% | 0.1481 | 0.078 | 1.9 | .0287 |

| Tubular atrophy | 23 | 30.43% | 33.08% | −0.0395 | 0.1025 | −0.39 | .6502 |

| Interstitial fibrosis | 23 | 26.09% | 21.55% | 0.0578 | 0.0856 | 0.68 | .2496 |

| Fibrous crescents | 23 | 13.04% | 14.56% | −0.0177 | 0.0587 | −0.3 | .6186 |

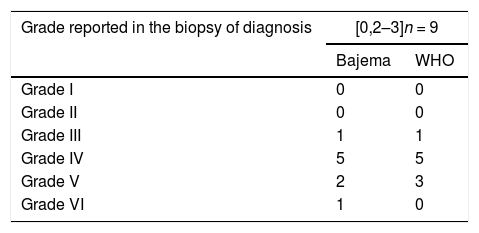

Table 6 describes the patients with GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 classified by the Bajema and the WHO scales. There were no significant differences between the initial classification according to both scales and the renal function at four years.

Patients with GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 at four years of follow-up of agreement, according to the classification of the initial.

| Grade reported in the biopsy of diagnosis | [0,2–3]n = 9 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bajema | WHO | |

| Grade I | 0 | 0 |

| Grade II | 0 | 0 |

| Grade III | 1 | 1 |

| Grade IV | 5 | 5 |

| Grade V | 2 | 3 |

| Grade VI | 1 | 0 |

WHO: World Health Organization.

In this retrospective study, which included 40 pediatric patients with LN from a middle-income country, the histopathological findings of RB showed a low level of agreement with the renal function when the biopsy was taken and at the last follow-up. The ideal to base a biopsy-guided clinical decision should be the precision in the evaluation of the renal histology with an interpathologist concordance. RB has an important implication to establish a possible prognosis and treatment of LN, in addition, is the idoneous method for ruling out other alterations such as thrombotic microangiopathy, podocytopathies tubulointerstitial nephritis or drug-induced nephrotoxicity, entities that also compromise the kidney in patients with lupus.20

Therefore, it should be considered that RB is the standard method for the diagnosis of LN and that renal involvement can be classified by the histopathological findings. The care guidelines in LN recommend to establish the prognosis and the management scheme according to the histopathological findings of the patients, taking into account the differences between the non-proliferative and the proliferative classes (class III, IV and III/IV + V). However, it is controversial whether it is an equally valid tool for the association with the renal prognosis.20

Several investigations have tried to define clinical and serological variables as predictors of renal prognosis, some cohorts describe the presence of proteinuria <0.8 g/day at 12 months after diagnosis as a marker of renal survival at 7 years, regardless the ethnicity and the histological class in adult patients. To date, none of the clinical results is able to be a reliable marker of long-term renal survival.21,22 Therefore, the possibility of having other biomarkers (histological or molecular) that prematurely can predict renal survival in patients with LN is questioned.

In our study, at the time of diagnosis, 28% (n = 9) of the patients with histopathological block had a GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. A correlation with the components of the ISN/RPS scale was made and there was evidence of low level of agreement in all histopathological characteristics for renal failure. In the activity index, karyorrhexis was predominant (34%), and in chronicity, tubular atrophy (27%); the 2 variables with insignificant kappa coefficient. In a study of 203 patients with LN, that compared the factors associated with tubulointerstitial inflammation and interstitial fibrosis or tubular atrophy, it was found that 30% of the patients, had a GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 at the time of the biopsy, 60% of them had moderate to severe tubulointerstitial inflammation and 70% experienced moderate to severe tubular atrophy, which are related with a poor renal response in the follow-up.23

At follow-up (median 2.3 years), 9 of 23 patients had a GFR < 60 mil/min/1.73 m2. The correlation with the items of the ISN/RPS scale was also conducted and there was evidence of low level of agreement in all the histopathological characteristics for renal failure. In the activity index, karyorrhexis was predominant (26%) and in chronicity, tubular atrophy and global segmental sclerosis (30.4%), the three variables with insignificant kappa coefficient. There are many efforts in the literature to find prognostic variables for renal survival, but with few satisfactory results. In cohorts of adult European patients with LN (n = 98), divided into proliferative and non-proliferative class, predictor histological markers for commitment were studied, according with the renal ISN/RPS classification, established as GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. The results regarding long-term renal survival were limited.24 Tao et al. assessed the possible association of the presence of crescents with certain clinical characteristics in 288 adult patients with LN. Although the general presence of cellular or fibrocellular crescents (that is, without discriminating the percentage of glomerular involvement) was described in 50.7% of the patients, no positive correlations between these and the decrease >30% in the GFR, a GFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2, requirement of dialysis at least for 6 months or death at a follow-up median of 76.5 months were reported. The studies in pediatric population are even more limited, with no clear evidence of histopathological markers that identify a renal prognosis.25

This study has several limitations: the first, due to its retrospective nature, some of the data were not available. The second, due the convenience sample size, the results of the study cannot be extrapolated to other clinical environments. The third, the samples were evaluated by a single pathologist (CJ), therefore, it was not possible to estimate the interobserver variability for the diagnosis. Despite this, the study has strengths. The patients are classified with the current management scale (ISN/RPS) revised by Bajema et al., unlike previous studies that offer the classifications with previous scales. In Colombia, Beltrán-Avendaño et al.25 described a cohort of 11 patients with lupus nephropathy and they found a renal involvement at the time of the RB in 74% of the cases and creatinine clearance reduced in 45%. The histopathological findings were classified according to the parameters of the WHO, but without the description of these in relation with renal survival.25 As already mentioned, previous studies in pediatric patients in Colombia with LN had clinically characterized this population and in one study, the lesions observed in the RB were correlated with the clinical manifestations and the treatment of the disease. Given the foregoing, this study has great strength, since it is the first to estimate the level of agreement between renal biopsies of pediatric patients with LN in Colombia and kidney function, evaluating it as a biomarker to predict kidney failure in our population.

ConclusionThe findings in the RB may be insufficient for assessing the prediction of the survival of the renal function, so the treatment and the prognosis of the patients with LN should be carried out using other biomarkers and clinical signs. Prospective studies that can confirm this hypothesis should be carried out.

FundingThis work has not received any type of funding.

Conflict of interestJaime Manuel Restrepo and Laura Torres-Canchala have a labor link with the institution.

We thank the Clinical Research Center of the Fundación Valle del Lili for the support given throughout the process.

Please cite this article as: Forero-Delgadillo J, Ochoa V, Torres-Canchala L, Duque N, Torres D, Jiménez C, et al. Acuerdo entre biopsia y función renal en pacientes pediátricos con nefritis lúpica. Un estudio retrospectivo. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2021;28:237–244.