This paper is the result of research, from the bioethics and bio-legal perspectives, on the existing guidelines in Colombia for the handling of pharmacogenomic and pharmacogenetic tests in clinical trials. Colombian legislation on this kind of research was reviewed and then compared with international and supranational standards. It was found that Colombia lacks specific legislation in this area, a situation that puts both participants and researchers at risk, from bioethical and legal perspectives. These risks should not be underestimated, as they compromise the ethical viability of clinical and basic research in our setting. In the end, a proposal, based on principles of ethics is made, proposing a series of actions for the creation and promotion nationwide of guidelines which can be used to shape legislation to be applied to protect the genetic data and the rights of subjects participating in these types of research studies in Colombia.

El presente artículo es el resultado de una investigación, desde las perspectivas bioética y biojurídica, acerca de los lineamientos existentes en Colombia para el manejo de las pruebas farmacogenómicas y farmacogenéticas en los ensayos clínicos. La revisión de la legislación existente en nuestro medio se comparó con estándares internacionales y los propuestos por organismos supranacionales. Se encontró que en Colombia falta una regulación específica en esta área, lo que expone a una serie de riesgos bioéticos y jurídicos a los participantes e investigadores. No se debe subestimar estos riesgos, pues comprometen la viabilidad ética de la investigación clínica y básica en nuestro medio. Al final, desde la perspectiva de la ética de los principios, se propone una serie de acciones para la creación y la promoción a escala nacional de lineamientos que sirvan para conformar una legislación aplicable a la protección de los datos genéticos y, por ende, los derechos de los sujetos que participan en esta clase de estudios de investigación en Colombia.

The Human Genome Project opened the door to pharmacogenomics and pharmacogenetics, which study variations in the genome of an organism and its response to a specific drug.1 Although this type of research is meant to contribute to the development of personalised medicine, it also raises important scientific and economic questions as well as legal, ethical and social considerations. In recent years, the pharmaceutical industry has taken a heightened interest in Latin America for the conduct of clinical research. Colombia is among the six countries where this type of clinical trial is conducted most often.2 The international regulatory authorities have published recommendations for incorporating it into the development of medicines.3,4

Initial efforts at genetic studies associated with clinical trials have been made in the field of oncology and have been aimed at evaluating safety and efficacy. The objective of this type of study now includes diagnostic tests and identification of new therapeutic targets.3 Its horizons have been broadened to specialisations such as psychiatry. This type of study is now typical in psychiatric clinical trials. This has sparked concern among independent ethics committee members and researchers, as many ethical and legal considerations have not been duly clarified.5

Colombia has a regulatory and ethical framework intended to protect research participant rights according to Resolution 8430 of 1993.6 However, accelerated technical and technological advances in this field, including pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics, have outpaced biolegal development.

Considerations related to test data generated in a study may have implications for participants' rights with regard to life, health, non-discrimination, information and shared benefits of science.7 These considerations take on a special significance when genetic data are included, and become especially important when they are included in clinical trials in psychiatry, the subjects of which are particularly vulnerable. The International Declaration on Human Genetic Data warns that "the collection, processing, use and storage of human genetic data have potential risks for the exercise and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms".8 Those risks include abuse and/or misappropriation of samples; hence, samples should be subject to a special protection regimen given their sensitive nature.9

Other countries already have standards for management of biological samples rooted in analogies to personal data in general. In Spain, for example, some specific requirements for the use of participant data must be established, depending on the study design and the information needs for the subject.10

From a bioethics perspective, in clinical trials that include studies of samples for pharmacogenomic and pharmacogenetic research, principles of autonomy, distributive justice, beneficence and non-maleficence are affected11 if there are no clear standards for the conduct of those studies. Uncertainty around handling of genetic samples and information derived from this handling creates a significant ethical dilemma due to the many possibilities for use of genetic material by study sponsors, which may conflict with bioethical principles.12 The requirements proposed by Ezekiel Emanuel for a clinical trial to be ethical include equitable selection13, which stresses the importance of avoiding enrolment of subjects who could not subsequently benefit from the results due to lack of access to expensive technologies only available in a private setting.

Therefore, the question of whether Colombian legislation, with its current standards, ensures protection of the genetic data and the rights of subjects who participate in these types of research studies was raised as a research topic with a view to proposing guidelines for effective protection of participants.

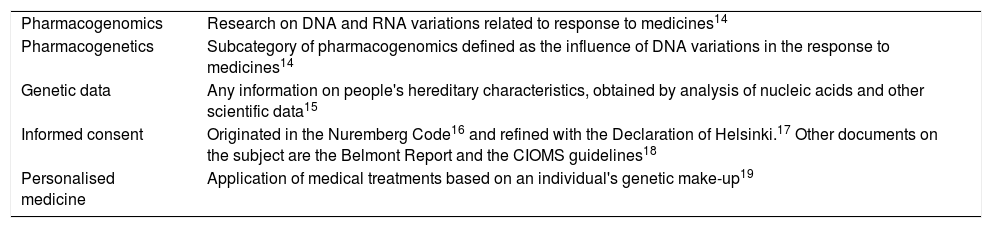

Basic concepts and content of standardsPreparation of possible national legislation regulating clinical trials with pharmacogenomic and pharmacogenetic tests requires an agreement on certain general terms and theoretical concepts in pharmacogenomics. A review of Colombian national legislation and binding supranational guidelines specifically related to this field had to be conducted (Tables 1–3).

Basic concepts in genetics and research.

| Pharmacogenomics | Research on DNA and RNA variations related to response to medicines14 |

| Pharmacogenetics | Subcategory of pharmacogenomics defined as the influence of DNA variations in the response to medicines14 |

| Genetic data | Any information on people's hereditary characteristics, obtained by analysis of nucleic acids and other scientific data15 |

| Informed consent | Originated in the Nuremberg Code16 and refined with the Declaration of Helsinki.17 Other documents on the subject are the Belmont Report and the CIOMS guidelines18 |

| Personalised medicine | Application of medical treatments based on an individual's genetic make-up19 |

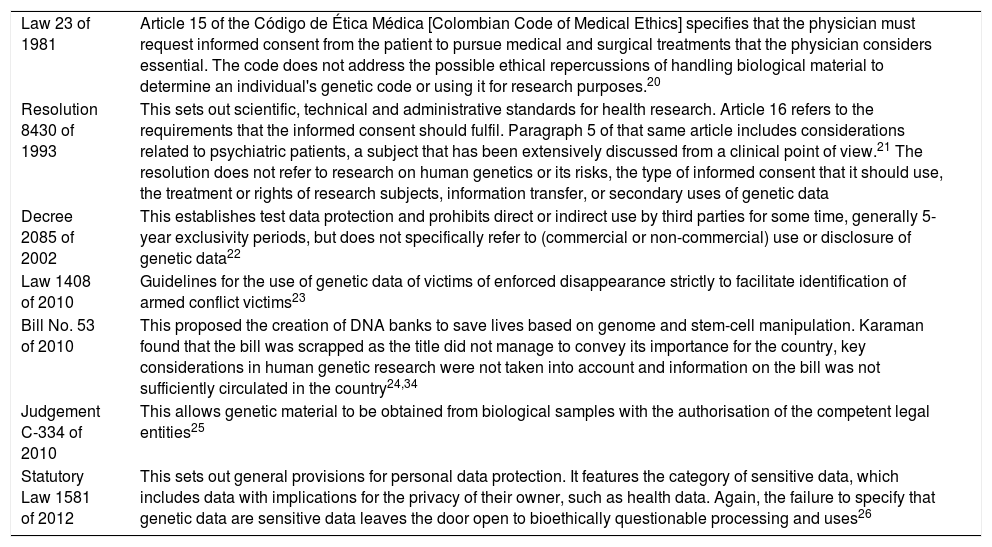

Colombian bioethical and biolegal guidelines on pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics.

| Law 23 of 1981 | Article 15 of the Código de Ética Médica [Colombian Code of Medical Ethics] specifies that the physician must request informed consent from the patient to pursue medical and surgical treatments that the physician considers essential. The code does not address the possible ethical repercussions of handling biological material to determine an individual's genetic code or using it for research purposes.20 |

| Resolution 8430 of 1993 | This sets out scientific, technical and administrative standards for health research. Article 16 refers to the requirements that the informed consent should fulfil. Paragraph 5 of that same article includes considerations related to psychiatric patients, a subject that has been extensively discussed from a clinical point of view.21 The resolution does not refer to research on human genetics or its risks, the type of informed consent that it should use, the treatment or rights of research subjects, information transfer, or secondary uses of genetic data |

| Decree 2085 of 2002 | This establishes test data protection and prohibits direct or indirect use by third parties for some time, generally 5-year exclusivity periods, but does not specifically refer to (commercial or non-commercial) use or disclosure of genetic data22 |

| Law 1408 of 2010 | Guidelines for the use of genetic data of victims of enforced disappearance strictly to facilitate identification of armed conflict victims23 |

| Bill No. 53 of 2010 | This proposed the creation of DNA banks to save lives based on genome and stem-cell manipulation. Karaman found that the bill was scrapped as the title did not manage to convey its importance for the country, key considerations in human genetic research were not taken into account and information on the bill was not sufficiently circulated in the country24,34 |

| Judgement C-334 of 2010 | This allows genetic material to be obtained from biological samples with the authorisation of the competent legal entities25 |

| Statutory Law 1581 of 2012 | This sets out general provisions for personal data protection. It features the category of sensitive data, which includes data with implications for the privacy of their owner, such as health data. Again, the failure to specify that genetic data are sensitive data leaves the door open to bioethically questionable processing and uses26 |

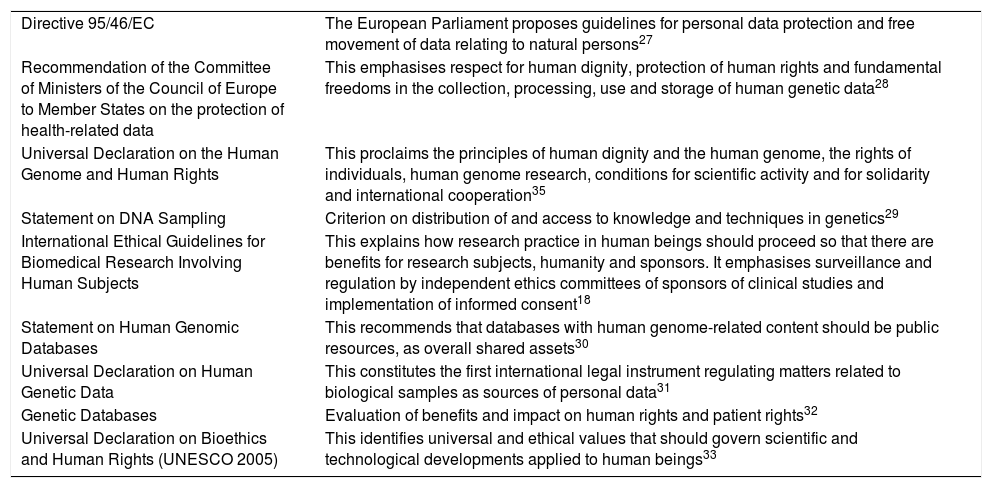

International bioethical and biolegal guidelines on pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics.

| Directive 95/46/EC | The European Parliament proposes guidelines for personal data protection and free movement of data relating to natural persons27 |

| Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe to Member States on the protection of health-related data | This emphasises respect for human dignity, protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the collection, processing, use and storage of human genetic data28 |

| Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights | This proclaims the principles of human dignity and the human genome, the rights of individuals, human genome research, conditions for scientific activity and for solidarity and international cooperation35 |

| Statement on DNA Sampling | Criterion on distribution of and access to knowledge and techniques in genetics29 |

| International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects | This explains how research practice in human beings should proceed so that there are benefits for research subjects, humanity and sponsors. It emphasises surveillance and regulation by independent ethics committees of sponsors of clinical studies and implementation of informed consent18 |

| Statement on Human Genomic Databases | This recommends that databases with human genome-related content should be public resources, as overall shared assets30 |

| Universal Declaration on Human Genetic Data | This constitutes the first international legal instrument regulating matters related to biological samples as sources of personal data31 |

| Genetic Databases | Evaluation of benefits and impact on human rights and patient rights32 |

| Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights (UNESCO 2005) | This identifies universal and ethical values that should govern scientific and technological developments applied to human beings33 |

All scientific developments may have major advantages, especially the development of medicines to treat diseases that are currently considered chronic and subject individuals, their families and society to intense suffering. Therefore, the conduct of clinical trials is considered appropriate and of paramount importance in all areas of medicine. Clinical trials occupy a particularly relevant place in psychiatry, as psychiatric diseases have multifactorial aetiologies and a high genetic load. Hence the advantage of pharmacogenomic and pharmacogenetic substudies as a way to optimise the efficacy, effectiveness, tolerability and safety of investigational medicinal products. However, rapid technical and technological advances in this field, including pharmacogenomics and pharmacogenetics, have outpaced biolegal development, and may entail risks for participants in clinical trials. That is why a regulatory and ethical framework has been created and is reflected in international instruments.

Based on the criteria issued by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), to incorporate pharmacogenomic and pharmacogenetic tests into the development of new medicines, this type of substudy started to be included in clinical trials. This has raised a dilemma for researchers, independent ethics committees and regulatory entities in Colombia because, although other countries conducting these studies have clear regulations, Colombia still has bioethical and biolegal gaps with regard to the conduct of pharmacogenomic and pharmacogenetic substudies which it has tried to fill without success, with the failure of Bill No. 53 of 2010, intended to establish DNA banks to save lives.34 There is an obvious lack of local regulations on genetic research, which should aim to contribute to the common good and, at the same time, benefit research subjects and the nation. The situation becomes more complex with the difficulty of integrating intellectual property standards, test data protection standards and pharmaceutical technical standards. The lack of legal guidelines has meant that there are no clear directives for independent ethics committees on the criteria for evaluating clinical trials with pharmacogenomic and pharmacogenetic substudies.

Incorporation of bioethical principles is necessary in developing legislation suited to new scientific and technological challenges.

The principle of autonomy is related to an individual's capacity for self-determination and free, voluntary decision-making. Practical application of the principle of autonomy is reflected in the informed consent. The consent process consists of much more than the formality of signing a document; it involves a process of communication between all players involved in which numerous difficulties may arise. This process has a special meaning in the field of psychiatry, as mental illness may affect subjects' capacity to consent, and may render them more vulnerable. The problems that arise between autonomy and genetics may derive from the fact that genes are intrinsic, private and irreversibly associated with the person. Therefore, when a clinical trial is not designed specifically for performing pharmacogenomic and pharmacogenetic tests, separate informed consent must be obtained for this purpose, so that subjects may exercise genuine autonomy without this interfering with their participation in the main study. This consent, furthermore, should enable the subject to withdraw or revoke his or her consent to participate in the study; not be general or flexible; restrict future uses of the sample; contain extensive information on all aspects of the study and the scope and duration of consent; and should include sample confidentiality and coding, notification of the results and consent to complementary studies.37

Although the use of biological samples for this type of study and the information deriving from them does not entail direct risks for the patient3 and the benefits are associated with subsequent scientific developments, the idea that pharmacogenomics will remain exploratory should be abandoned37, as it has the potential to reveal highly sensitive and important information on subjects.

Based on the principle of beneficence38, the right to privacy and non-discrimination, which may be jeopardised by improper use of genetic data, should be respected. Therefore, the level of confidentiality conferred upon samples in this type of research should preserve the above-mentioned rights. Practical application of this principle is reflected in matters related to the coding of the sample donated by the subject. International consensuses such as the 2007 Conference on Harmonisation41 have clear standards for sample coding that do not recommend using either identifiable or anonymous samples. The particular case of anonymised samples precludes contacting subjects should any information pertinent to their health be discovered; it also precludes follow-up and auditing, bearing in mind that these samples are not stored in Colombia.

In the area of psychiatry, coding should not depend on clinical trial type. The most suitable level of protection is double coding of samples5, since this method grants the subject continued rights to his or her sample with regard to the information derived from the sample and also gives the investigator the option of correlating the findings of genetic studies with the efficacy and safety of the investigational medicinal product, which is one of the goals of personalised medicine.

Now, the principle of distributive justice as it relates to pharmacogenomic research has been extensively addressed in the Ethical, Legal and Social Implications (ELSI) of Pharmacogenomics in Developing Countries document from the World Health Organization39, which stipulates that products and resources derived from pharmacogenomics be distributed in a just and equitable manner. It is warned that, for this principle to be genuinely applied, it should be evaluated from the perspective of the individual and the country as a whole.

The promise of personalised medicine is aimed at developing increasingly safe and effective methods for a particular individual, but it is also a highly lucrative strategy for pharmaceutical companies. One example is the possibility of "drug resuscitation", since these could only be used in responding populations, or even placing medicines that have already been taken off the market back on the market.

The country's appropriation of innovative technological developments such as pharmacogenomics and its conduct of its own studies in this area hold promise for a positive impact on public health policies, since having knowledge of the genetic profile of the country's population may enable the country to formulate a highly cost-effective strategy.

From an individual point of view, this principle raises the issue of ownership of genetic information. From this, the following are derived: complex matters relating to donation of biological samples in clinical trials, characteristics and requirements of biobanks36, ownership of test data and their commercial value, and the limits of the protection of the confidentiality of genetic data due to their sensitive nature. Institutions such as the Biobank in the United Kingdom and other such institutions in the United States have determined that the biobank is the owner of the biological samples therein. Some researchers and research participants have tried to reclaim ownership of these biological samples, but have not succeeded.40 The outlook grows even more complicated in view of the fact that current Colombian regulatory development entails intellectual property standards that may promote the commercial value of research test data7, at the expense of the protection of the genetic data of research subjects due to a lack of relevant biolegal developments. In this regard, the level of data protection is fundamental to the protection of the interests and rights of research subjects.

The principle of justice is also closely related to the right to share in research benefits set out in the Universal Declaration of Bioethics and Human Rights. A statement from the Human Genome Organisation (HUGO) ethics committee stresses the growing importance of this right as a strategy for reducing socioeconomic disparities in developing countries with regard to using innovative technologies such as pharmacogenomics for the benefit of their populations.

Advances in the genetic study phase in clinical trials are far outstripping advances in personalised medicine and their implications for health systems.

The risks related to the increase in health information (privacy, confidentiality and discrimination) which are intimately linked to people's dignity; the implications for the doctor–patient relationship, due to new requirements in genetic knowledge and application thereof to the diagnosis and treatment of diseases; and the healthcare disparities that could arise amidst existing high costs and lead to limitations on coverage have been considered.42

This study visualises and suggests strategies for collaborative efforts given the possibilities presented by new health technologies. A discussion of all emerging implications for the healthcare system lies beyond the scope of this article.

ConclusionsBased on international guidelines related to use of genetic data in research on the protection of sensitive data, a number of guidelines are proposed in light of bioethical principles to serve as a foundation for new biolegal developments for performing pharmacogenomic and pharmacogenetic tests in psychiatry clinical trials in Colombia, since the current regulatory framework does not include specific regulations for handling this type of sample that take the above-mentioned risks into consideration. The proposed guidelines are as follows:

- 1

Information on the conduct of an exploratory genomic substudy must be clearly specified in the study protocol from the start.

- 2

This type of test must be accompanied by a specific informed consent form that complies with all guidelines set out in Resolution 8430 as well as the guidelines of the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS). It must supply clear objective and sufficient information specifying the purposes for which the data are to be used, the method and duration of data storage, and the risks and consequences for the subject.

- 3

In cases in which other future uses for already donated samples are envisioned, subjects should be contacted for further consent.

- 4

Consent to the performance of this type of test must be absolutely freely granted and must not determine whether the subject is enrolled in the clinical trial.

- 5

The most suitable level of protection with clinical research is double coding, which offers a balance that helps participants take action concerning their samples with regard to withdrawing consent and returning information. This would be in keeping with the principles of autonomy, distributive justice and shared benefits.

- 6

It is recommended that all players involved in the conduct of clinical trials actively participate in developing national standards.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Very special thanks to Dr María Alejandra Echavarría Arcila for her optimism and valuable contributions.

Please cite this article as: Padrón APP, Gil FDR. ¿Qué lineamientos bioéticos y biojurídicos se debe seguir al realizar pruebas farmacogenéticas y farmacogenómicas en ensayos clínicos de psiquiatría en Colombia para proteger los datos genéticos y los derechos de los sujetos de investigación? Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:57–63.