People with mental health conditions frequently attend primary care centers, but these conditions are underdiagnosed and undertreated. The objective of this paper is to describe the model and the findings of the implementation of a technology-based model of care for depression and unhealthy alcohol use in primary care centers in Colombia.

MethodsBetween February 2018 and March 2020, we implemented a technology-based model of care for depression and unhealthy alcohol use, following a modified stepped wedge methodology, in six urban and rural primary care centers in Colombia. The model included a series of steps aimed at screening patients attending medical appointments with general practitioners and supporting the diagnosis and treatment given by the general practitioner. We describe the model, its implementation and the characteristics of the screened and assessed patients.

ResultsDuring the implementation period, we conducted 22,354 screenings among 16,188 patients. The observed rate of general practitioner (GP)-confirmed depression diagnosis was 10.1% and of GP-confirmed diagnosis of unhealthy alcohol use was 1.3%. Patients with a depression diagnosis were primarily middle-aged women, while patients with unhealthy alcohol use were mainly young adult men.

DiscussionThe provision of training and technology-based strategies to screen patients and support the decision-making of GPs during the medical appointment enhanced the diagnosis and care provision of patients with depression and unhealthy alcohol use. However, time constraints, as well as structural and cultural barriers, were challenges for the implementation of the model, and the model should take into account local values, policies and resources to guarantee its long-term sustainability. As such, the long-term sustainability of the model will depend on the alignment of different stakeholders, including decision-makers, institutions, insurers, GPs, patients and communities, to reduce the amount of patients seeking medical care whose mental health conditions remain undetected, and therefore untreated, and to ensure an appropriate response to the demand for mental healthcare that was revealed by the implementation of our model.

Las personas con condiciones de salud mental son frecuentes en atención primaria, pero estas condiciones son subdiagnosticadas y poco tratadas. El objetivo de este trabajo es describir el modelo y los resultados de la implementación de un modelo, basado en tecnología, para depresión y uso riesgoso de alcohol, en centros de atención primaria en Colombia.

MétodosEntre febrero de 2018 y marzo de 2020 se implementó, siguiendo una metodología modificada de stepped-wedge, un modelo de atención, basado en la tecnología, para depresión y uso riesgoso de alcohol en seis centros de atención primaria, urbanos y rurales, en Colombia. El modelo incluye una serie de pasos dirigidos a la detección de pacientes que acuden a cita con médicos generales y apoyar el diagnóstico y el tratamiento por parte del médico general. Describimos el modelo, la implementación, y las características de los pacientes tamizados y evaluados.

ResultadosDurante la implementación, se realizaron 22,354 tamizaciones en 16,188 pacientes. La tasa observada de depresión confirmada por médico general fue del 10.1% y de uso riesgoso de alcohol fue del 1,3%. Los pacientes con diagnóstico de depresión fueron principalmente mujeres de mediana edad, mientras que los pacientes con uso riesgoso de alcohol fueron principalmente hombres adultos jóvenes.

DiscusiónProveer capacitación y estrategias basadas en tecnología para tamizar pacientes y apoyar la toma de decisiones de los médicos durante la cita médica mejoró el diagnóstico y la atención de los pacientes con depresión y uso riesgoso de alcohol. Sin embargo, las limitaciones de tiempo, así como las barreras estructurales y culturales, fueron desafíos para la implementación del modelo, por lo que el modelo debe tener en cuenta los valores, las políticas y los recursos locales para garantizar su sostenibilidad a largo plazo. Por lo tanto, la sostenibilidad a largo plazo del modelo dependerá de la alineación de actores, incluidos los actores, incluidos los tomadores de decisiones, las instituciones, las aseguradoras, los médicos, los pacientes y las comunidades, para reducir la cantidad de pacientes que buscan atención médica cuyas condiciones de salud mental siguen sin detectarse y, por lo tanto, sin manejo, y para garantizar una respuesta adecuada a la demanda de atención de salud mental que se observó con la implementación de nuestro modelo.

Mental health conditions are estimated to cause about 7.4% of the disease burden worldwide,1 and significantly contribute to disability and death. In Colombia, according to the 2015 Colombia National Mental Health Survey, the prevalence of mental health disorders was about 9.6% (95%CI 8.8–10.5%)2 Mental health conditions, including depression and substance use disorders, related in part to long-term internal armed conflict, are concerning issues for public health both in Colombia and the broader region. One specific concern is that although mental health problems are high, access to mental health care is low, not only in Colombia but also in Latin America broadly. Indeed, it has been estimated that in Latin America, up to 37% of patients with severe mental illness, 59% with major depression and 71% with alcohol use disorders are in need of treatment but do not receive care.3 In Colombia, it has been shown that only 3 out of each 10 persons with any mental health problem requested care.4

Increasing the detection, diagnosis and treatment of mental health disorders is a priority worldwide, to reduce the burden of these conditions on public health. This goal is at the core of the Mental Health Gap Action Program (mhGAP) launched by the World Health Organization in 2008, which includes scaling up strategies and activities for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders, with priority of low- and middle-income countries.5 In Colombia, efforts to embrace this plan include reinforcing primary-care based mental health care, as a strategy to reduce the gaps in detection, diagnosis and care provision of mental health.6 Digital technology has been identified as a key element with a great potential to build new models of mental health service delivery in primary care, capable of providing access to mental healthcare among remote and neglected communities.7 Leveraging technologies for health provision can also contribute to reaching other goals in mental healthcare care, such as enhancing the implementation of evidence-based recommendations and improving the training and skills development for mental health care among a non-specialized healthcare workforce.

The Project DIADA is a US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)-funded project, aimed at developing, implementing, and testing a technology-based healthcare model in primary care in Colombia. Within the project framework, extensive formative research has been conducted to improve our understanding about the mobile technology use patterns among patients from primary care centers, but also to capture and interpret the perspectives of patients, providers and administrative staff about the challenges and opportunities for the implementation of a technology-assisted model of care for mental health conditions in primary care. Formative research is understood as the research that is conducted prior to the implementation of a model, aimed at improving our understanding about the characteristics, interests, and necessities of the community in relation to a health issue. On the basis of this preliminary work, we designed and implemented a technology-based healthcare model in six primary care sites located in six different cities in Colombia. The model aimed at improving the detection, diagnosis and care of patients with depression and unhealthy alcohol use, in primary care centers. The objective of this paper is to describe the model and the findings of the model implementation since its launch in February 2018. A complete study protocol paper of the DIADA project is in press elsewhere.8

MethodsStudy designThe model is implemented within the framework of an NIMH-funded “Scale-Up Hubs” cooperative agreement (to scale up access to evidence-based mental health interventions) aimed at conducting systematic, multi-site mental health implementation research in both rural and urban primary care settings with a broad group of partners in the US and Latin America.9,10 In this case, the implementation research included the design and the assessment of the implementation of the mental health care proposed model at the participating centers.

Model implementationUsing a modified stepped wedge experimental design, the model was implemented approximately every six months in a new primary care study site. The study was first implemented at a primary care center located in Bogotá DC, as a pilot in February 2018 and then it was fully implemented in April 2018. In August 2018, the model was implemented in a rural primary care hospital located in Santa Rosa de Viterbo, a small town from the department of Boyacá. Afterwards, in February 2019, the study was implemented in Duitama, a semi-urban setting located also in Boyacá. In August 2019, the model was implemented in Guasca, a small town nearby the north of Bogotá. Finally, in February 2020, the study was implemented in Soacha, a small town nearby south of Bogotá and in Armero-Guayabal, a town that received the survivors of the 1985 Armero Tragedy due to the eruption of the Nevado del Ruiz volcano. Before the study implementation in each site, we prepared each site by conducting standardized trainings of administrative staff and healthcare providers in screening, diagnosis and treatment of depression and unhealthy alcohol use. We also ensured the site was logistically and technically prepared for the project (e.g., set-up the technology infrastructure for the project).

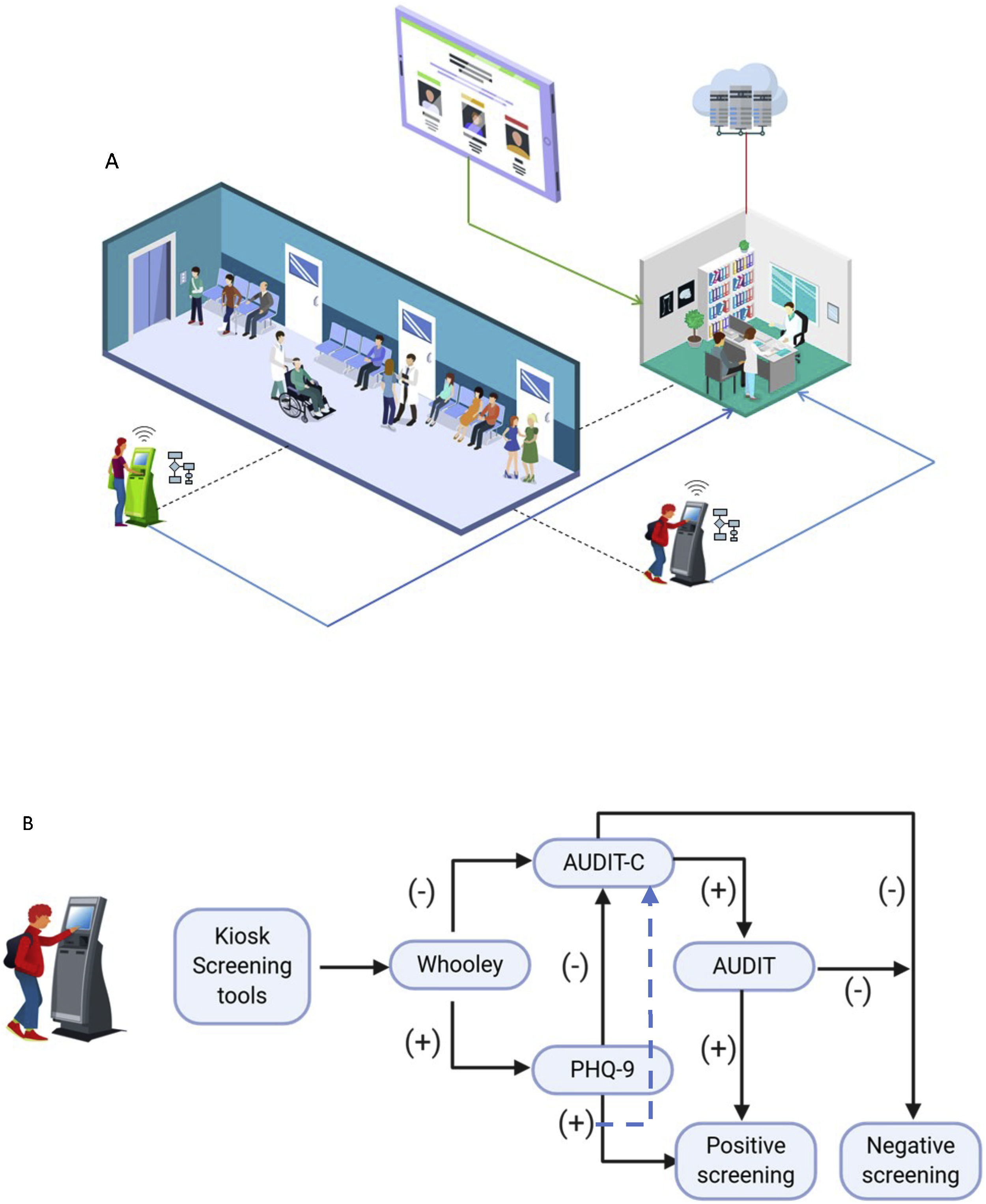

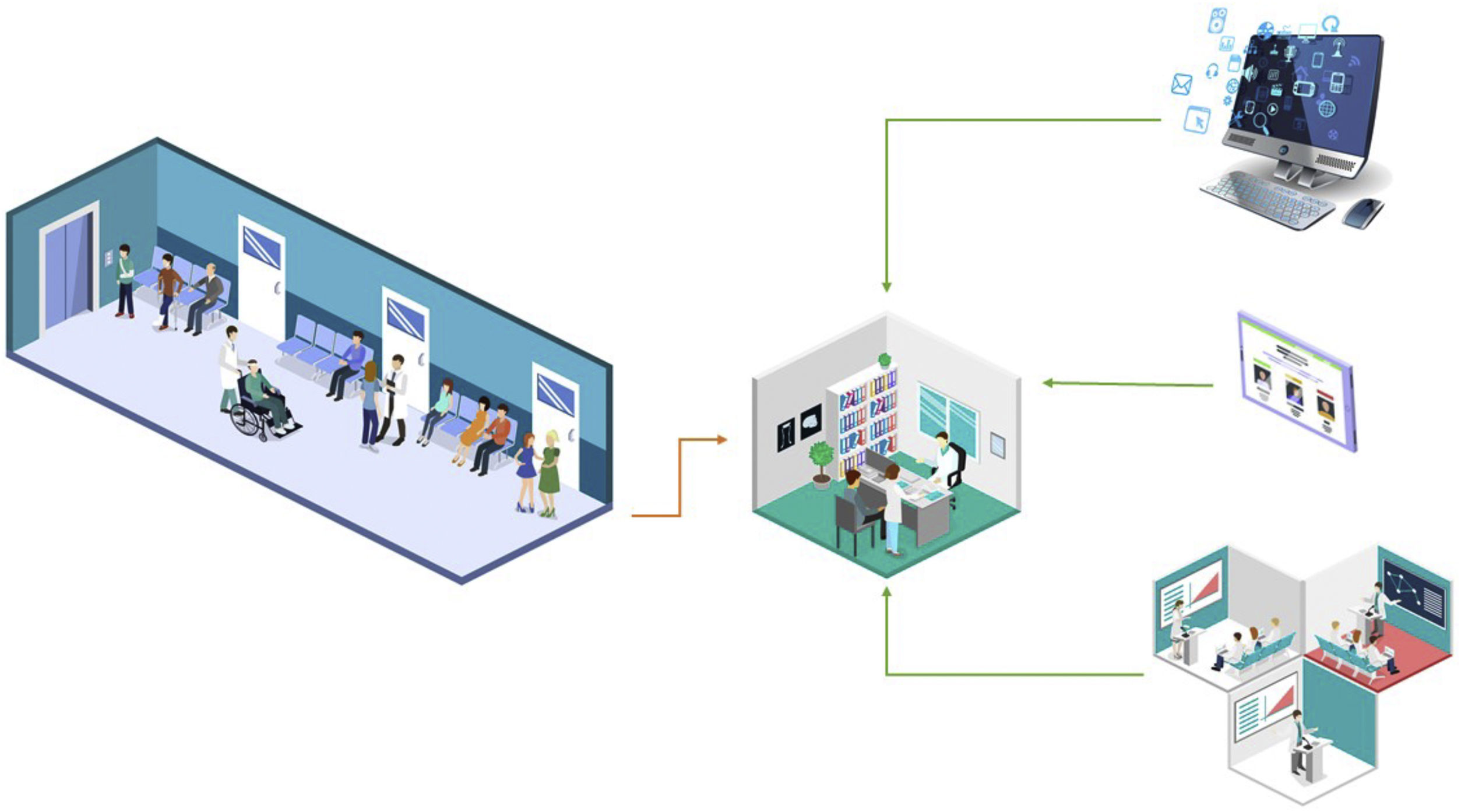

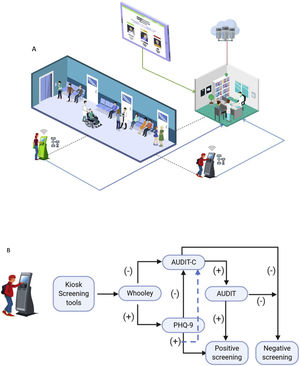

Model descriptionThe innovative approach of our technology-based model is aimed at facilitating the integration of mental health care into the process that patients follow when seeking primary care medical attention. First, we developed a screening system with two different modules: one for patients and the other for health care providers. All adult patients waiting for a General Practitioner (GP)-ambulatory appointment completed an electronic screening in the waiting room of the study site are screened, using a specially designed stand-alone, touch-screen electronic kiosk. The kiosk included an identification scanner to read the patients biographical data registered in the back of their national identification card. A tablet-based kiosk presents the screening tools for depression (Whooley and PHQ-9) and unhealthy alcohol use (AUDIT-C and AUDIT) consecutively and a printer produces a ticket with the patient’s screening results (Fig. 1). The kiosk is located at a private site in the waiting rooms, and a research assistant is available to help patients to navigate the screening questionnaires in case they asked for help. The patient is instructed to hand the ticket with the screening results to the GP at the beginning of the appointment. Second, the results of the screening tests are automatically uploaded to a server that allowed the GPs to access each patient’s results through the providers module to reassess the symptoms and confirm or rule out the diagnosis (Fig. 2). We provided the GPs access to the system via the providers’ module in the tablets at their offices. The providers’ module also contains decision tools to aid the physician in reassessing the symptoms and the diagnosis of the problem and guide the treatment. These recommendations presented on the module are based on the Colombian Clinical Practice Guidelines for depression and unhealthy alcohol use developed by co-investigators of this project. Additionally, the GPs receive training about the diagnosis and treatment recommendations at the beginning of the model’s implementation in each study site, and the training is regularly reinforced (in a monthly basis) in meetings held with psychiatrist co-investigators of the project. During these meetings, the GPs receive feedback about the model performance and are invited to bring severe or complicated cases for discussion with the specialists.

Model description – Screening phase.

Part A. The general population aged eighteen years old or older uses kiosks available in the waiting room (dotted lines). Each kiosk has a Wi-Fi connection and follows an algorithm with screening tools (See part B). The kiosk provides patients with printed scores of screening results. The information also goes to the physicians who consult screening results (continuous blue lines) on the Tablet with updated information about diagnosis confirmation, and recommended treatment and follow-up (Continuous green line). All the data coming from the kiosk and physician’s actions using tablet guidelines are stored in the cloud (Continuous red line). Part B. Description of the screening algorithm used at the kiosks. First, patients are screened for depression with the Whooley test 21 and for unhealthy alcohol use with Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption (AUDIT-C) 22. If these are positive, full screening of depression is made with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) 12 and of unhealthy alcohol use with the AUDIT test 13.

Model description – Diagnosis phase.

Patients with positive screening for depression or alcohol use disorder are assessed for the physician. The physician has access to the project website and to clinical guidelines for treating depression and unhealthy alcohol use. Easy-to-access and updated information about training material is available in tablets at each GP office. All of the physicians have face-to-face training and feedback by project psychiatrists.

The patients with GP-confirmed diagnosis of depression or unhealthy alcohol use are invited to participate in the study and, after providing their informed consent, participants are granted a one-year access to the mobile application Laddr® (Square2 Systems, Inc).11 Laddr is a digital therapeutic that offers science-based self-regulation monitoring and health behavior change tools via an integrated platform to a wide array of populations.

The study follow-up of the patients consists of calls or face-to-face appointments at the primary care site to explore the evolution of the patients’ symptoms and the impact of their mental health on their overall health and job status, among others. The participants’ clinical status is followed for one year by our trained research assistants.

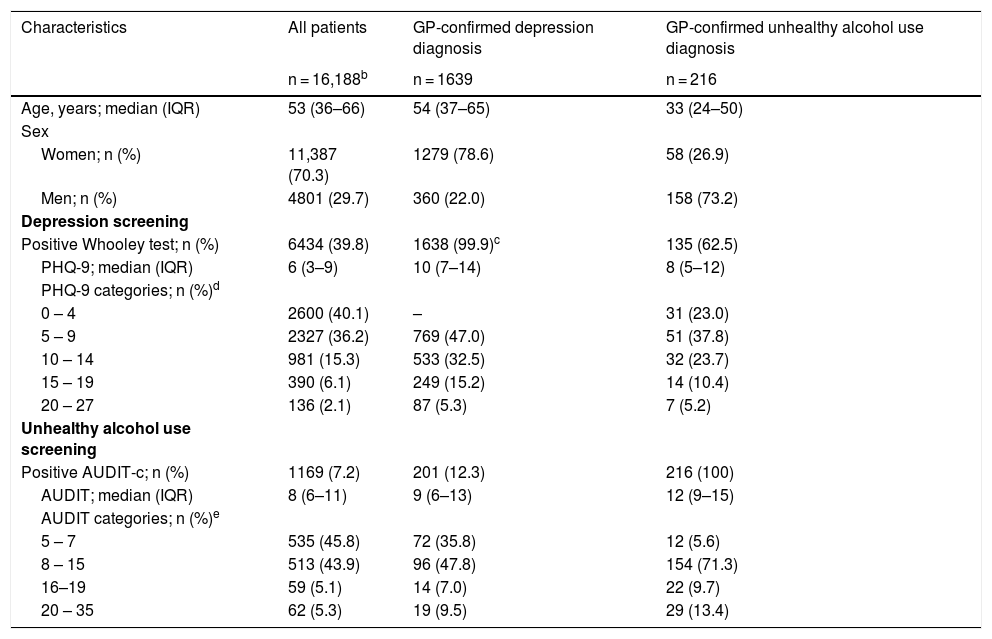

Statistical analysesThe data of the screening and GP-confirmation results of each patient are stored in a Web-based platform. These data were exported and analyzed to Stata 14 software. We have conducted a descriptive analysis of the demographic characteristics of the patients, as well as the distribution of the screening results and GP-confirmed diagnosis. For patients that were screened more than once during the study implementation, we describe the first visit or the visit where the patient received a GP-confirmed diagnosis. We use median and interquartile range (percentiles 25th and 75th) to describe continuous variables and absolute and relative frequencies to describe categorical variables. We describe the screened population, those with GP-confirmed diagnosis of depression and those with GP-confirmed diagnosis of unhealthy alcohol use. Additionally, we describe the frequency of GP-confirmed diagnosis of each condition according to screening categories (Table 1).

Patients characteristics.a

| Characteristics | All patients | GP-confirmed depression diagnosis | GP-confirmed unhealthy alcohol use diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 16,188b | n = 1639 | n = 216 | |

| Age, years; median (IQR) | 53 (36–66) | 54 (37–65) | 33 (24–50) |

| Sex | |||

| Women; n (%) | 11,387 (70.3) | 1279 (78.6) | 58 (26.9) |

| Men; n (%) | 4801 (29.7) | 360 (22.0) | 158 (73.2) |

| Depression screening | |||

| Positive Whooley test; n (%) | 6434 (39.8) | 1638 (99.9)c | 135 (62.5) |

| PHQ-9; median (IQR) | 6 (3–9) | 10 (7–14) | 8 (5–12) |

| PHQ-9 categories; n (%)d | |||

| 0 – 4 | 2600 (40.1) | – | 31 (23.0) |

| 5 – 9 | 2327 (36.2) | 769 (47.0) | 51 (37.8) |

| 10 – 14 | 981 (15.3) | 533 (32.5) | 32 (23.7) |

| 15 – 19 | 390 (6.1) | 249 (15.2) | 14 (10.4) |

| 20 – 27 | 136 (2.1) | 87 (5.3) | 7 (5.2) |

| Unhealthy alcohol use screening | |||

| Positive AUDIT-c; n (%) | 1169 (7.2) | 201 (12.3) | 216 (100) |

| AUDIT; median (IQR) | 8 (6–11) | 9 (6–13) | 12 (9–15) |

| AUDIT categories; n (%)e | |||

| 5 – 7 | 535 (45.8) | 72 (35.8) | 12 (5.6) |

| 8 – 15 | 513 (43.9) | 96 (47.8) | 154 (71.3) |

| 16–19 | 59 (5.1) | 14 (7.0) | 22 (9.7) |

| 20 – 35 | 62 (5.3) | 19 (9.5) | 29 (13.4) |

Between February 2018 and March 2020, we implemented our model in six urban, semi-rural and rural primary care sites, and we conducted 22,354 screenings among 16,188 patients. Overall, the majority of the population was female (70.3%) and the median age was 53 years (IQR = 36–66). About 60% of the patients (n = 3834) reported at least mild depression symptoms in at least one screening and about 54% of the patients reported at least unhealthy alcohol use in at least one screening.

The overall prevalence of GP-confirmed depression diagnosis was 10.1% (1639/16,188 patients). The median age of these patients was 54 years (IQR = 37–65) and most of them were female (78.6%). Patients’ median score on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9, a validated screener for depression symptoms (12)) was 10 (IQR = 7–14). Most of those with GP-confirmed depression had mild symptoms of depression (47.0%), whereas about 20% of them had moderate-to-severe (PHQ-9 15–19) or severe (PHQ-9 20–27) depression symptoms. Patients with GP-confirmed diagnosis of depression were more likely to report at least risky alcohol consumption, according to AUDIT (a validated measure for unhealthy alcohol use (13)), than overall population (64.2% vs 54.2%).

The overall prevalence of GP-confirmed unhealthy alcohol use diagnosis was 1.3% (216/16,188 patients). The median age of these patients was 33 years (IQR = 24–50), and most of the population was male (73.2%). Their median AUDIT score was 12 (IQR = 9–15), and 71.3% of these patients reported risky alcohol use. Moreover, 23.1% of them had an AUDIT above 16, indicating probable dependence. Additionally, patients with GP-confirmed unhealthy alcohol use were more likely to report at least moderate depression symptoms relative to the overall population (39.2% vs 23.7%).

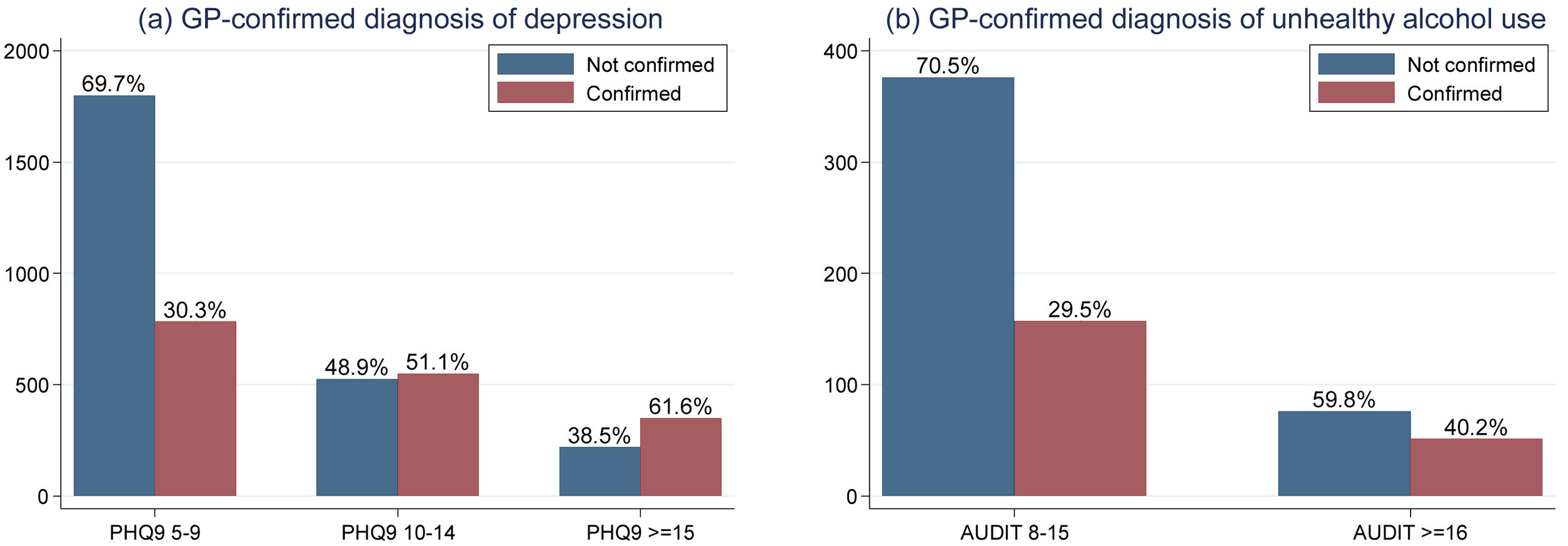

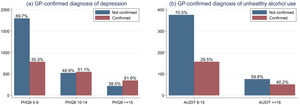

Fig. 3 shows the distribution of GP-confirmed diagnosis of depression and unhealthy alcohol use. Overall, patients with a score of PHQ-9 ≥ 15 (moderate-to-severe or severe symptoms) were more likely to receive a GP-confirmation of depression. About half of patients with moderate depression symptoms (PHQ-9 scores between 10–14) received a GP-confirmed depression diagnosis. Among the participants with mild depression symptoms (PQH-9 scores 5–9), the GP-confirmed depression diagnosis rate was about one third. The GP-confirmation rate of unhealthy alcohol use was lower than that of depression. One-third of patients classified with risky alcohol consumption (AUDIT scores 8–15) were confirmed by the GP, and only 40% of the patients classified with hazardous alcohol consumption or possible dependence by AUDIT score (AUDIT ≥ 16) were confirmed by the GP.

DiscussionThe aim of DIADA project is to implement and assess a model of care to detect, diagnose and treat patients with depression and/or unhealthy alcohol use in primary care centers in Colombia. Between February 2018 and March 2020, we implemented our model in six urban and rural primary care sites. Overall, the prevalence of GP-confirmed depression diagnosis was 10.1% and of GP-confirmed unhealthy alcohol use was 1.3% Patients with depression diagnosis were primarily middle-aged women, while patients with unhealthy alcohol use were mainly young adult men. Patients with unhealthy alcohol use were more likely to report depression symptoms.

Our model proved itself to be a useful strategy to detect patients with depressive symptoms and unhealthy alcohol use in primary care centers from Colombia. Our findings are in agreement with other studies that have found a relatively high prevalence of depression and/or unhealthy alcohol use among patients attending primary care centers for diverse medical conditions.14 We made use of technology to develop a model of care that addressed some of the identified barriers for detection of mental health conditions, such as low awareness about these conditions among GPs and patients and lack of training among GPs about how to address these conditions.14 Overall, our model used inexpensive devices (tablets and kiosk) and technology, with high acceptability by our users. Without our model, a significant number of patients with these conditions would have remained undetected and, consequently, not treated.

The prevalence of GP-confirmed diagnosis of depression in our sample was about 10.1%, which is higher than the lifetime prevalence of mood disorders in the 2015 Colombian National Survey of Mental Health (2015 NSMH), reported at 7.1% (95%CI 6.1–8.2%) among adult (aged 18 years or older) women and at 6.3% (95%CI 5.1–7.8%) among adult men.15 The prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use in our sample was 1.3%, which was lower than the prevalence observed in the 2015 NSMH, where the prevalence of risky alcohol consumption was 16% (95%CI 14.4–17.8) among men and 9.1% (95%I 8.0–10.3) among women aged 18–44 years.16 These findings can be explained because most of our sample were women and patients seeking care for medical conditions, which are factors associated with both higher prevalence of depression and lower alcohol intake.4,17,18 Additionally, we observed that patients with GP-confirmed diagnosis of unhealthy alcohol use were more likely to report a higher prevalence of depression symptoms, which is consistent with the higher frequency of at least one depression symptom among participants with risky alcohol intake in the 2015 NSMH.16

Given the characteristics of the mental health care model we implemented, it is not possible to identify which of its attributes are most relevant for its successful implementation, although some elements were identified as fundamental. First, a research assistant was available to systematically invite all patients in the waiting room to conduct the screening and to help them navigate the screening tool in case they needed. Although the model was designed to be fully integrated into the study site processes, the fact that the screening was not a requisite for the GP-appointment and that it was somewhat voluntary, the absence of the research assistant would have likely led to low screening rates. But the presence of the screening tool and the research assistant likely facilitated screening. This finding is in agreement with the study of Diez-Canseco et al., who found that an easy-to-use screening tool administered by primary healthcare providers increased the willingness of the patients to be screened and to seek mental healthcare.14 Second, the kiosk screening was electronically linked to the tablets located at the GP-offices via Wi-Fi, so the GPs could review the patients’ screening results and access a decision-support tool and patient-specific evidence-based recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Therefore, the tablet supported the GP decision-making process for diagnosing and treating patients that had been previously detected through screening, thus potentially increasing the effectiveness of our implementation strategy as well as patients’ outcomes. Third, we trained and provided feedback on a monthly basis to the GPs on depression and unhealthy alcohol use diagnosis and care, including regular assessment of specific cases detected both by them on their practice and by us during the follow-up. These sessions were led by psychiatrists from the project. Previous studies have demonstrated that providing training and decision-support tools contribute to an increased detection of patients with mental health conditions and reduce the barriers for treatment.14,18,19 Finally, we maintained a fluid communication with each institution’s leadership, through regular assessments of the model integration and site-specific feedback, in order to troubleshoot issues in the study as they arose.

Yet, our study uncovered some opportunities for implementation improvement. First, the kiosk was located in the waiting room of the study sites. And, even though we tried to locate it as much as possible in a low traffic place, it may have been in too much of a public location. Having the kiosk in the waiting room may have increased the interest in it, but may also have led some patients to feel exposed while answering questions about their depression symptoms or alcohol consumption patterns, potentially contributing to inaccurate responses or screening rejection. Second, the Wi-Fi was unstable in some sites, especially in the rural sites, thus delaying the information transfer from the kiosks to the GP-tablet. We managed these issues by offering backup material both in the office’s computers and in paper form. However, manual consultation of these resources increased the process times, during an appointment that is already burdened by the paper work and the short amount of time providers have with each patient. The limited time per patient was a frequently mentioned issue for the model’s implementation, especially when the patient condition required some specific feedback and discussion with the GP. Short time for the consultation has also been mentioned as a barrier for implementation of mental health interventions in primary care, as it competes with other tasks in providing care for the primary reason the patient sought consultation.14 Third, the fact that the tablet was not integrated into the electronic health record (EHR) of the study site was an issue for GPs. They had to navigate both the office computer and the tablet project,20 increasing the cognitive load by longer processing time and multitasking during the appointment. Where available, we created a bookmark in the web browser of the GP office computer, to reduce their need to use several devices, as the screening system is web-based. The lack of integration of the screening system with the EHR was also a barrier to ensure that all patients who had a positive screening at the kiosk were addressed by the GP, as in some cases, patients would forget to give the ticket with the screening results to the GP. However, this was a practical decision based on the interoperability limitations of the EHR used in each site and the lack of a EHR in some of the rural sites. During the feedback sessions, the GPs were frequently instructed to request the ticket, as part of the appointment tasks.

Other challenges during the study implementation were mostly related to structural and cultural barriers in relation with depression and unhealthy alcohol use, some of which were reported during the qualitative phase of the project. First, a relevant structural barrier was the skepticism of some GPs regarding the model’s reach and the relevance of the mental health conditions themselves. This would lead to missed confirmations, even when patients had reported severe symptoms of either depression and/or unhealthy alcohol use (Fig. 3). To address this issue, we repeatedly explained and underscored the importance of embracing mental health as part of healthcare via constant feedback, retraining and consultation, not only for the GPs but also for the institutions, to align the multiple actors with the objectives of the model. Through regular meetings in which we offered feedback and engaged in case-based discussion, as well as site-specific reports of results, we observed an improvement in the confirmation rates of diagnoses. We also encouraged GPs to invite the patients to use the mobile app Laddr and to use it themselves, as a resource to aid the treatment of the patients. Second, a relevant cultural barrier that was identified throughout the implementation is the need to adapt the screening tools to be culturally appropriate, a factor that may impact their accuracy.14 In particular, the accuracy of the AUDIT tool to screen unhealthy alcohol use was affected in at least one rural site, where a traditional and very popular alcoholic drink, named chicha, is often assumed to be non-alcoholic, since it is homemade and derives from the fermentation of sugar cane. In this case, the research assistant was instrumental to gauge the chicha consumption of the patient to improve the accuracy of the responses. Third, an identified cultural barrier for the model’s implementation was the stigma of depression symptoms and normalization of unhealthy alcohol consumption in Colombian population, both among patients and GPs, which affected both the willingness of the patients to be screened, some of whom would refuse it, as well as missed confirmations by the GPs, who would occasionally underestimate the problematic consumption. We addressed these barriers by involving the institutions to enforce, as much as possible, the screening as a requisite for the GP-consultation, but also by developing educational multimedia material and policy briefs to convey a message about the relevance of these conditions for the wellbeing and quality of life of the patients. Nevertheless, as of today, these issues and others are yet to be assessed and addressed together with stakeholders, institutions leaders, insurers, GPs, patients and communities, to align the model’s goals and implementation with local values, policies and resources.

Addressing these barriers for the model implementation will be necessary to drive its long-term sustainability. Among other factors, the study sites would need to assess what components of the model should be adapted to their local values, policies and resources, while maintaining key aspects of the model, such as (1) universal screening as a strategy to increase the awareness among both patients and GPs about these mental health conditions and (2) technology-supported decision-making for GPs to enhance their skills to address and treat these conditions, thus reducing the need for specialized care and consequently, the barriers for patients’ mental health care access. It would be key for the model to get fully integrated into the patients’ care flow at the care sites, and it may be useful to maintain dedicated personnel supporting the universal screening and scheduling regular training of GPs in mental health conditions. Furthermore, the sites may need to adapt and increase the mental health services they offer to care for their patients with diagnosed depression and unhealthy alcohol use. For example, an unintended finding of our model was that patients would frequently report feeling heard and taken care of during the study follow-up calls and appointments, even though these were intended to track clinical status and not to provide therapeutic intervention. Also, the remote follow-up with patients that was offered within the model may be important for sustainability, as it may further reduce barriers for care, especially for patients with conditions that do not require intensive or in-person appointments.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, our study demonstrated that a technology-based model of care can contribute to the increased detection and care provision of depression and unhealthy alcohol use among patients in primary care sites in Colombia. We found a higher prevalence of depression and a lower prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use, compared to overall population, which was an expected finding, given our sample was primarily women and patients seeking medical care. Provision of training and technology-based strategies to screen patients and to support decision-making of GPs during the medical appointment enhanced the diagnosis and care provision of patients with depression and unhealthy alcohol use. However, time constraints, as well as structural and cultural barriers, are challenges for the implementation of the model, and the model should account for local values, policies and resources to warrant the long-term sustainability. Therefore, the long-term sustainability of the model will depend on the alignment of several actors, including stakeholders, institution leaders, insurers, GPs, patients and communities, to reduce the amount of patients seeking medical care whose mental health conditions remain un-detected and therefore, un-treated, and to warrant an appropriate response to the demand for mental health care that was revealed by the implementation of our model.

FundingResearch reported here was funded under award number 1U19MH109988 by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Multiple Principal Investigators: Dr. Lisa A. Marsch and Dr. Carlos Gómez-Restrepo). The contents are solely the opinion of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Conflict of interestDr. Marsch is affiliated with the business that developed the mobile intervention platform used in this research. This relationship is extensively managed by Dr. Marsch and her academic institution. The other authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Please cite this article as: Gómez-Restrepo C, Cepeda M, Torrey W, Castro S, Uribe-Restrepoa JM, Suárez-Obando F, et al. El proyecto DIADA: un modelo de atención, basado en tecnología, para depresión y uso riesgoso de alcohol en centros de atención primaria en Colombia. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:4–12.