One of the most important moments in a doctor’s life occurs when they do a medical residency. This period imposes stress and academic demands, which, together with the educational environment, allows for greater or lesser mental wellbeing. The objective of this study was to determine how the educational environment and mental wellbeing of medical residents are related.

MethodsAnalytical cross-sectional study, in residents of clinical-surgical specialties. The educational environment was assessed using the Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure (PHEEM), and mental wellbeing was assessed with the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS). Pearson’s linear correlation was determined. Informed consent and approval by the university ethics committee were obtained.

ResultsThe study population comprised 131 students, 43.8% male, with a median age of 28 years (interquartile range 4). In total, 87.9% of residents answered the survey. Of these, 65.9% were doing medical residencies and 34.1% surgical residencies. The mean PHEEM score was 107.96 ± 18.88, the positive emotions subscale was 29.32 ± 5.18 and positive functioning 23.61 ± 3.57, with a mean total mental wellbeing of 52.96 ± 8.44. A positive and moderate correlation was found between the total PHEEM score and each of the two mental wellbeing subscales (p < 0.001).

ConclusionsA positive correlation was found between a better perception of the educational environment and mental wellbeing by residents of clinical and surgical specialties with greater mental wellbeing.

Uno de los momentos más importantes en la vida de un médico ocurre cuando realiza la especialización médica. Este periodo impone estrés y exigencias académicas, lo cual, junto con el ambiente educacional, permite un mayor o menor bienestar mental. El objetivo del estudio es determinar cómo se relacionan el ambiente educacional y el bienestar mental de los residentes de Medicina.

MétodosEstudio transversal analítico en residentes de especialidades clínico-quirúrgicas. El ambiente educacional se evaluó mediante la escala Postgraduate Hospital Educational Envioroment Meassure (PHEEM) y el bienestar mental, con la escala de Warwick-Edinburgh (EBMWE). Se determinó la correlación lineal de Pearson. Se tomó el consentimiento informado y se obtuvo la aprobación del comité de ética universitario.

ResultadosIntegraron la población de estudio 131 estudiantes, el 43,8% varones, con una mediana de edad de 28 [intervalo intercuartílico, 4] años. El 87,9% de los residentes respondieron a la encuesta. Hubo un 65,9% de posgrados médicos y un 34,1% de quirúrgicos. La puntuación media en la PHEEM fue de 107,96 ± 18,88; en la subescala de emociones positivas, 29,32 ± 5,18 y en funcionamiento positivo, 23,61 ± 3,57, con una media total de bienestar mental de 52,96 ± 8,44. Se encontró una moderada correlación positiva entre puntuación total de la PHEEM y cada una de las 2 subescalas de bienestar mental (p < 0,001).

ConclusionesSe encontró una correlación positiva entre una mejor percepción del ambiente educacional y el bienestar mental de los residentes de especialidades clínicas-quirúrgicas con mayor bienestar mental.

Medicine has been considered a profession of sacrifice, great responsibility, total dedication to patients and postponement of personal interest. This idealised and long-standing vision has been re-evaluated in the light of numerous social, economic and political changes that have come up against the ideals of life of physicians with lawsuits and criticism about the quality and dehumanisation of the service they provide.1

Historically, physicians have disregarded the effects of stress on professional conduct and a person’s physical and mental health. More recently, this situation has gained prominence in academia and institutional accreditation processes that set standards to ensure the quality and continuous improvement of medical education.2–4

Within medical education, two aspects have recently gained prominence. Firstly, the educational environment, the climate or atmosphere surrounding the medical resident’s training process, predicts achievement, satisfaction and professional success.5–8 This is determined by multiple factors such as curriculum, assignments, teachers, and student motivation.9 The second aspect is mental or psychological well-being, a complex, multidimensional construct related to satisfaction and happiness.10 These two factors are related in a complex way with other factors specific to the subject and the sociocultural context, which enable either a reduction or an increase of the intrinsic burden of medical training.11

The Universidad CES has had a medicine programme for 40 years that trains students specialising in medical and surgical fields. In order to continuously improve the quality of medical education provided, the objective of this study was to determine if the characteristics of the educational environment are related to the mental well-being of residents.

MethodsSampleAn observational, cross-sectional and analytical study was conducted with clinical and surgical postgraduate residents from the medical school of a private university in the city of Medellín, Colombia. The reference population comprised 149 residents enrolled in the second semester of 2016. All available subjects were included in the sample. No exclusion criteria were defined. All the participants gave their informed consent, information was anonymous, and its confidentiality was guaranteed. The study was approved by the university’s Research Ethics Committee.

VariablesThe dependent variable was mental well-being measured according to the Warwick–Edinburgh scale and the independent variables were educational environment measured by the Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure (PHEEM) scale and sociodemographic variables (age, sex, marital status, children, place of origin and residence, financial support for the residency, among others) and those related to the residency.

InstrumentsThe researchers designed a survey for the study that included sociodemographic data and data related to the financing of postgraduate studies. Two psychometric instruments were included. The PHEEM was created in the United Kingdom in 2005 by Roff et al.12 and validated in several countries, such as Brazil, Greece, Singapore, Australia, Chile, Iran or Saudi Arabia,13–15 and assesses the hospital environment of clinical postgraduate programmes. The version used in this study was that of Riquelme et al.16 used in a group of 125 sixth- and seventh-year Chilean undergraduate medical students, which obtained a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95.

The PHEEM consists of 40 Likert-type questions with five response options, from strongly agree (four points) to strongly disagree (zero points). The minimum score is zero and the maximum, 160: with 0–40 being a very poor educational environment; 41–80 an educational environment with a lot of problems; 81–120 an educational environment that is more positive than negative, and 121–160 an excellent educational environment.

The Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS) measures positive aspects of mental health over the past two weeks. It is an ordinal scale comprising 14 statements referring to hedonic and eudaemonic aspects of mental well-being. Each item is answered on the basis of a five-point Likert scale from “None of the time” to “All of the time”, and the final result is obtained from the sum of all the items (from 14 to 70 points). Higher scores indicate a higher degree of mental well-being.

The Spanish adaptation of the WEMWBS was carried out by Serrani17 in an Argentine population of 910 older adults of both sexes with α = 0.89, indicating a high level of internal consistency. The test-retest reliability was in an average interval of 90 ± 47 days. The intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.91 (p = 0.001), which indicates stability over time. This validation showed a bifactorial structure; the first factor includes optimism, happiness, self-esteem, self-confidence and resilience, and is termed, positive emotions (minimum of eight and maximum of 40 points), and the second factor includes commitment, competence, relationships and personal meaning, and is termed, positive functioning (minimum of six and maximum of 30 points).

BiasesIn order to minimise selection bias, all residents enrolled in the second semester of 2016 were invited to participate and the researchers who applied the instruments directly motivated the residents to participate in the study, thereby avoiding self-selection and losses that can determine conditioning characteristics.

There is an information bias through the awareness-raising of the community of residents regarding the importance of the information that they would be providing for the improvement of academic programmes and the guarantee of anonymity regarding the information provided by them. Participation was voluntary, and the researchers who requested the information from the residents were not teachers and did not have administrative ties to the university. Two instruments with good psychometric properties in terms of reliability were also used.

Analysis of the informationThe information was analysed with the SPSS statistical software version 21.0, licensed. For the description of age, normality tests were performed; the median [interquartile range] is presented because the variable did not meet the assumptions of normality (Shapiro–Wilk test) or equality of variances in the groups compared (Levene’s test). The categorical variables (sex, aspects related to mental well-being and the educational environment) were presented using absolute and relative frequencies.

For the bivariate analysis, the correlation coefficient was used to measure the strength of association of the educational environment and mental well-being variables; for this, Pearson’s linear correlation was used because the variables were adjusted to normal distribution according to the Shapiro–Wilk and equality of variances tests (Levene’s test).

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the university's research ethics committee. All participants gave their informed consent. The confidentiality of and respect for the information provided were guaranteed.

ResultsSociodemographic characteristicsThe sample was comprised of 131 students out of the 147 enrolled in the academic period studied, which represents a participation rate of 87.9% of the residents of the university's postgraduate courses. Individuals who did not participate were out of town or out of the country on international rotations.

Of the participants, 43.8% (56) were male and 56.3% (72) female; the mean age was 28 [4] (range, 22–50) years. Regarding the place of residence, 80.9% (106) lived in urban areas and 19.1% (25) in rural areas. Eighty-four point four percent of participants (108) came from Antioquia and 15.6% (20) from outside Antioquia. Eight point four percent (11) had children and 90.1% (118) did not. Regarding marital status, 77.2% (98) were single; 16.5% (21), were married; 0.8% (1), were widowed; 4.7% (6) were in a cohabiting relationship and 0.8% (1), were divorced. The financing of the studies was achieved as follows: 57.7% (75) through parents or family; 20.8% (27) with loans; 11.5% (15) with the student’s own resources; 6.9% (9) with the partner’s resources and 3.1% (4) by other means. Eighty-seven point five percent (112) did not have dependants and 12.5% (16) did. Regarding financial aspects related to the studies, 55.3% (63) will have to pay back a financial debt at the end of the specialisation and 54.6% (71) used the credit scholarship as a means of financing the studies (Table 1).

Sociodemographic and residency-related characteristics of the study population.

| Sex | |

| Male | 56 (43.8) |

| Female | 72 (56.3) |

| Age (years) | 28 [4] |

| Place of residence | |

| Urban | 106 (84.4) |

| Rural | 25 (19.1) |

| Origin | |

| Antioquia | 108 (84.4) |

| Outside Antioquia | 20 (15.6) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 98 (77.2) |

| Married | 21 (16.5) |

| Widowed | 1 (0.8) |

| Cohabiting | 6 (4.7) |

| Divorced | 1 (0.8) |

| Children | |

| Yes | 11 (8.4) |

| No | 118 (90.1) |

| Financial support resources | |

| Own | 15 (11.5) |

| Partner’s | 9 (6.9) |

| Parents’ or family | 75 (57.3) |

| Loan | 27 (20.6) |

| Other | 4 (3.1) |

| Payment of debt at the end of the residency | |

| Yes | 63 (55.3) |

| No | 51 (44.7) |

| Has dependants | |

| Yes | 16 (12.5) |

| No | 112 (87.5) |

| Scholarship credit | |

| Yes | 71 (54.6) |

| No | 59 (45.4) |

| Undergraduate medical course at CES | |

| Yes | 68 (52.7) |

| No | 61 (47.3) |

Values are expressed in terms of n (%) or median [interquartile range].

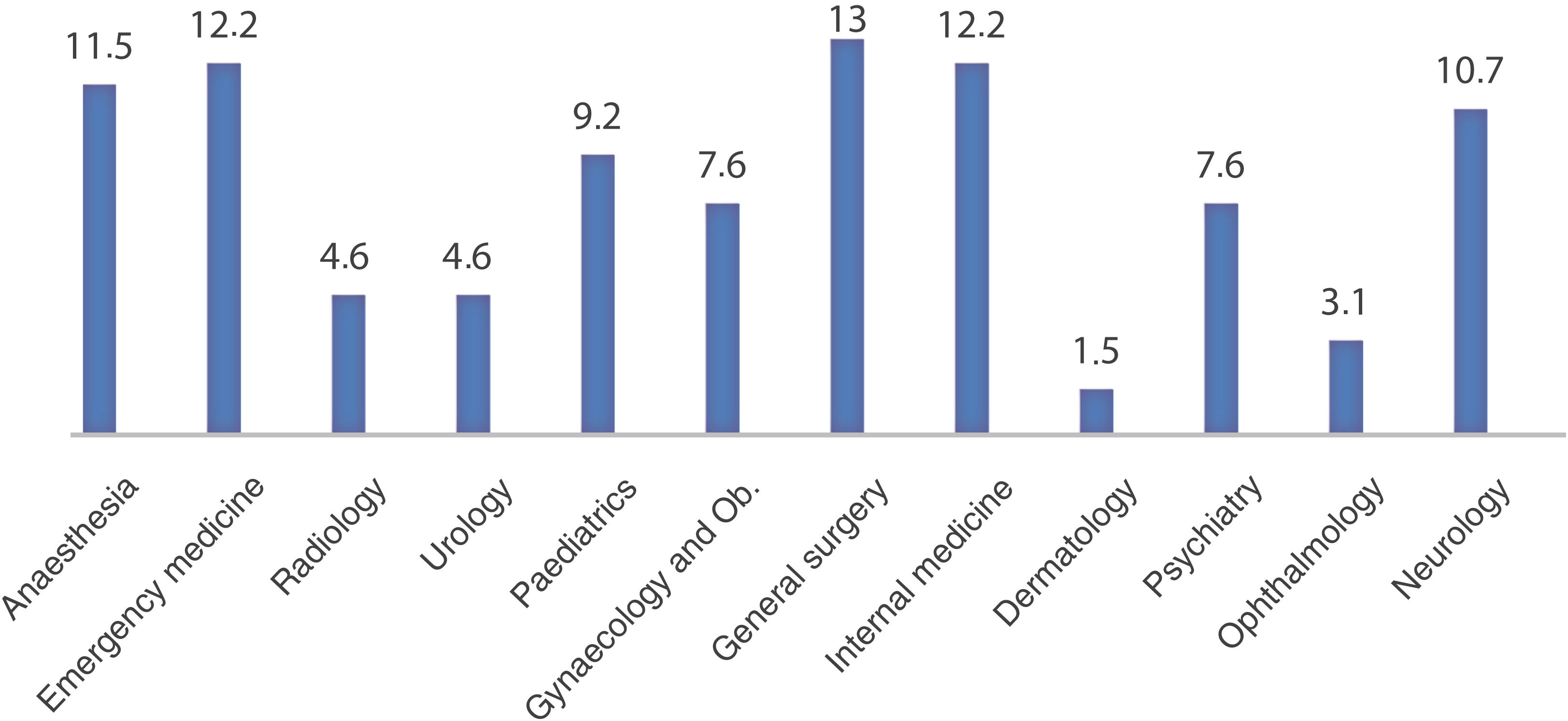

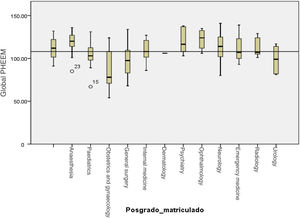

Fifty-two point seven percent (68) of the residents were CES undergraduate medical students and 47.3% (61) came from other universities. Most of the students were in medical postgraduate courses (65.9%) and, to a lesser extent, in surgical postgraduate courses (34.1%). The largest number of students by postgraduate degree belonged to General Surgery (17), followed by Emergency Medicine (16) and Dermatology (2) (Fig. 1).

Educational environmentThe total average of the PHEEM scale was 107.96 ± 18.88, which indicates a more positive than negative perception of the educational environment, with room for improvement.

The aspects for at least 20% of the residents showed a less favourable perception of the educational environment were: a) entertainment outside of rotation activities (64.1%); b) informative rotation handbook (34.6%); c) chance to participate in other educational activities without it interfering with classes or assessment tests of other courses (24.6%); d) frequent feedback from teachers (22.9%); e)good counselling opportunities when failing (21.4%), and f) feedback regarding strengths and weaknesses (20.0%) (Table 2).

Percentage distribution of the responses to the educational environment scale (PHEEM) by residents.

| Strongly disagree and disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Agree and strongly agree | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The programme provides information about hours of work | 9.1 | 13.0 | 77.9 |

| My clinical teachers set clear expectations | 9.2 | 16.8 | 74.1 |

| I have protected educational time in this rotation | 18.4 | 6.2 | 75.4 |

| I had an informative induction programme | 5.3 | 7.6 | 87.0 |

| I have the appropriate level of responsibility in this rotation | 2.3 | 9.2 | 88.0 |

| I have good clinical supervision at all times | 8.5 | 8.5 | 83.1 |

| There is racism in this rotation | 89.2 | 3.1 | 7.7 |

| I have to perform inappropriate tasks for my stage of training | 70.5 | 14.7 | 14.7 |

| There is an informative student handbook for this rotation | 34.6 | 20.8 | 44.6 |

| My clinical teachers have good communication skills | 9.9 | 25.2 | 74.8 |

| I am bleeped inappropriately | 75.6 | 11.5 | 12.9 |

| I am able to participate in other educational events | 24.6 | 17.7 | 57.7 |

| There is sex discrimination in this rotation | 87.0 | 8.4 | 4.6 |

| There are clear clinical protocols in this rotation | 10.0 | 16.2 | 73.9 |

| My clinical teachers are enthusiastic | 6.1 | 17.6 | 76.3 |

| I have good collaboration with other students in my grade | 3.1 | 6.1 | 90.8 |

| My hours are suitable | 13.8 | 15.4 | 70.8 |

| I have the opportunity to provide continuity of care | 9.2 | 19.1 | 80.9 |

| I have suitable access to careers advice | 6.1 | 22.9 | 71.0 |

| This hospital has good accommodation when on call | 6.1 | 5.3 | 88.5 |

| Access to a needs relevant educational programme | 6.1 | 22.9 | 77.0 |

| I get regular feedback from seniors | 22.9 | 34.4 | 65.7 |

| My clinical teachers are well organised | 5.3 | 23.7 | 76.3 |

| I feel physically safe within the clinical environment (hospital/outpatient) | 5.4 | 3.8 | 90.7 |

| There is a no-blame culture in this rotation | 20.0 | 13.1 | 66.9 |

| There are adequate catering facilities when on call (cafeteria) | 14.6 | 10.8 | 73.7 |

| I have enough learning opportunities for my needs | 4.6 | 9.2 | 86.3 |

| My clinical teachers have good teaching skills | 2.3 | 3.1 | 94.6 |

| I feel part of a team working here | 5.3 | 13.0 | 81.7 |

| I have opportunities to acquire the appropriate practical procedures for my grade | 6.1 | 6.9 | 87.0 |

| My clinical teachers are accessible | 3.1 | 10.8 | 86.2 |

| My workload in this job is fine | 15.4 | 10.0 | 74.6 |

| Senior staff utilise learning opportunities effectively | 7.7 | 10.8 | 81.5 |

| The training in this post makes me feel ready to be a physician | 3.1 | 19.9 | 87.0 |

| My clinical teachers have good mentoring skills | 5.4 | 14.7 | 79.9 |

| I get a lot of enjoyment out of my present rotation | 64.1 | 18.3 | 17.6 |

| My teachers encourage me to be an independent learner | 5.3 | 10.7 | 84.0 |

| There are good counselling opportunities for students who fail to complete their training satisfactorily | 21.4 | 37.4 | 41.3 |

| My clinical teachers provide me with good feedback on my strengths and weaknesses | 20.0 | 18.5 | 61.5 |

| My clinical teachers promote an atmosphere of mutual respect | 5.4 | 11.5 | 83.1 |

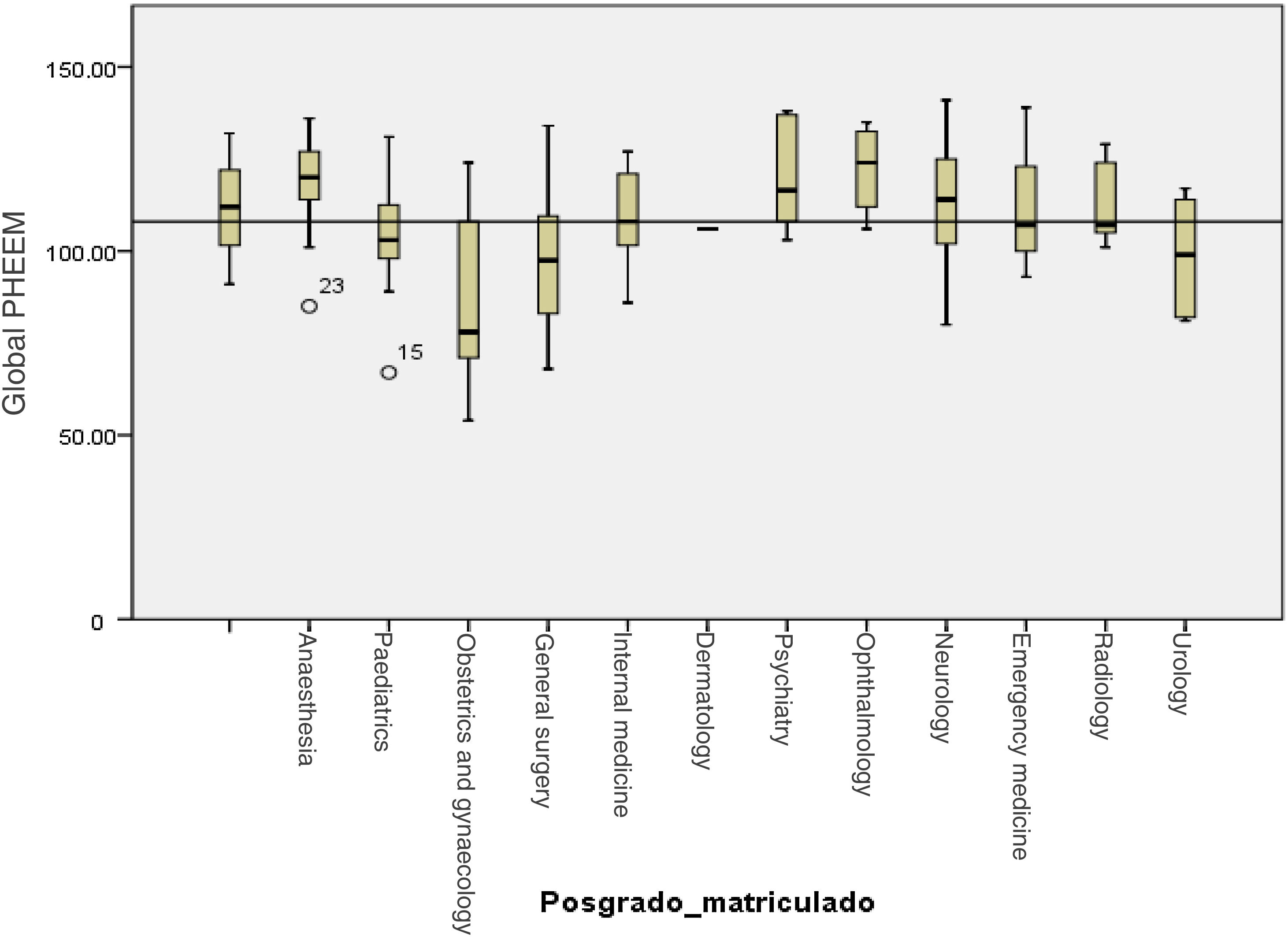

The analysis by medical specialties found that in general the environment is evaluated more positively by the residents of Psychiatry, Ophthalmology, Anaesthesiology and Radiology (Fig. 2).

On the global PHEEM scale, the maximum score of 109 demonstrates an educational environment that is more positive than negative, but with areas for improvement. When evaluating each subscale, it was found that the perception of the role of autonomy was 38 points (maximum, 56), which indicates a positive perception; the perception of the teaching role was 45 points (maximum, 60), which corresponds to excellent perception. Finally, the perception of social support subscale obtained 26 points (maximum, 44), which indicates more positive than negative aspects.

Mental well-beingRegarding mental well-being, mean scores were found in the positive emotions subscale of 29.32% ± 5.18% and in positive functioning, 23.61% ± 3.57% for a total mean of 52.96% ± 8.44%.

The aspects for which the residents declared lower mental well-being with response rates ≥20% were: a) “I’ve been feeling relaxed” (43.4%), and b) “I’ve had energy to spare” (38.9%) (Table 3).

Percentage distribution of responses on the Warwick–Edinburgh Scale.

| None of the time-rarely | Some of the time | Often-all of the time | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I’ve been feeling optimistic about the future | 3.8 | 17.6 | 78.6 |

| I’ve been feeling useful | 3.8 | 19.1 | 77.1 |

| I’ve been feeling relaxed | 43.4 | 31.0 | 25.7 |

| I’ve been feeling interested in other people | 3.1 | 15.4 | 84.6 |

| I’ve had energy to spare | 38.9 | 39.7 | 21.4 |

| I’ve been dealing with problems well | 3.8 | 26.0 | 70.2 |

| I’ve been thinking clearly | 6.1 | 25.2 | 67.7 |

| I’ve been feeling good about myself | 9.9 | 21.4 | 65.7 |

| I’ve been feeling close to other people | 7.7 | 29.2 | 70.7 |

| I’ve been feeling confident in myself | 11.5 | 22.9 | 65.6 |

| I’ve been able to make up my own mind about things | 5.3 | 12.2 | 82.5 |

| I’ve been feeling loved | 5.4 | 21.5 | 78.4 |

| I’ve been interested in new things | 7.6 | 26.7 | 63.3 |

| I’ve been feeling cheerful | 4.6 | 22.1 | 77.8 |

A positive correlation was found between the total PHEEM score and the two mental well-being subscales (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Correlation between global score on the global educational environment scale and the mental well-being sub-scales.

| Global PHEEM | Positive emotions | Positive functioning | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global PHEEM | |||

| Pearson’s correlation | 1 | 0.486 | 0.461 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| n | 115 | 112 | 114 |

| Positive emotions | |||

| Pearson’s correlation | 0.486 | 1 | 0.835 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| n | 112 | 128 | 126 |

| Positive functioning | |||

| Pearson’s correlation | 0.461 | 0.835 | 1 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| n | 114 | 126 | 129 |

This study explored the mental well-being and the perception of the educational environment in residents of medical and surgical specialties in Medellín, Colombia. The main finding was the positive correlation found between these two determining aspects of medical training, which implies that a better perception of the resident about the educational environment is correlated with a higher level of mental well-being.

There is growing interest in studying how medical residents’ perceptions of the educational environment is linked to mental health issues such as burnout and mental illness.18–20 Studies have also been carried out to determine how the perception of the educational environment is related to the mental well-being of residents; however, as it is a complex construct, attempts have often been made to study mental well-being based on the presence or absence of mental illnesses and not as a specific quality,21 although “well-being during medical residency” is more than the absence of depression and burnout.22 No other studies were identified that have used the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale and the PHEEM in a group of residents.

The overall mean score on the PHEEM scale in our study indicates a more positive than negative educational environment with areas for improvement. In Latin America, studies of the educational environment have been carried out with the PHEEM scale before. A Chilean study23 and an Argentinian study24 obtained results similar to ours, 105.09 ± 22.46 and 106.8 ± 13.98 respectively, while two Bolivian studies25,26 demonstrated a less positive perception (83.5 and 75.16).

One study27conducted recently with 153 Internal Medicine residents in Singapore found a mean on the PHEEM scale of 112.23 ± 16.7 points, higher than our results, with no differences by sex or training level. Among the areas with opportunity for improvement, the residents identified the excessive workload that takes time away from studying and the absence of faculty supervisors at the practice sites for timely feedback.

Our results are not homogeneous between the different specialties. The least positive perception in residents of Obstetrics, General Surgery and Urology, in our case, implied less mental well-being in this group of physicians. This is consistent with what was found by a study28 that was recently carried out with the PHEEM scale, applied to a group of Moroccan residents regarding their environment

Similarly, a Pakistani study29 which included 368 residents of Gynaecology and Obstetrics found a mean in the PHEEM of 63.68 ± 29.60 points, which indicates an inadequate educational environment that does not meet the expected standards.

Mental well-being is recognised as an important component of individual health. Poor mental well-being is a risk factor for mental illnesses. In a study carried out with nursing students from Slovenia and Ireland, an average value was found in the WEMWBS of 53.08 ± 8.70 and 45.79 ± 7.75, with values closer to ours in the Slovakian study. No studies were found that have used the mental well-being scale in students or graduate physicians.30

The well-being of physicians has become a topic of great general and scientific interest.31–36 Different initiatives have arisen from this.22,37 Among them, is that of the US Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), which proposes the following individual and organisational strategies21: a) commitment of faculty, departments and curricula to the well-being of residents; b) address the issue of well-being in monthly faculty meetings and annually screen for burnout and check well-being of teachers, residents and students; c) optimal shift schedules, post-shift time and rest time; d) written policies and commitments; e) right to sick leave and medical care, maternity and paternity leave; f) mission statement; g) uninterrupted access to mental health resources; h) training in mindfulness exercises and mindfulness mobile phone applications; i) accessible exercise facilities and ability to use them; j) healthy lunch and snacks; k) easy access to water and coffee; l) access to medical and dental services; m) social events (happy hour, holiday party); n) graduation events; o) team building exercises; p) physical spaces for study; q) peer tutoring, mentors; r) positive psychology, coaching; s) life outside the hospital, and t) financial advice.

LimitationsThe following limitations must be taken into account. As it was a cross-sectional study, the correlations found are not causal. The PHEEM instrument is based on the subjective perception of residents at a given time and space, so it cannot be taken as an “objective reality”. When inquiring about situations that occurred in the past, a recall bias is possible. To minimise this, the PHEEM scale inquires about what happened during the last rotation, which means events are more recent and easier to remember. Not all factors that determine a resident’s mental well-being, such as the possible existence of mental or physical illness, family dysfunction, and other aspects related to mental well-being, were evaluated in this study. The PHEEM and Warwick–Edinburgh scales are validated in Spanish, but not in Colombia.

Among the strengths of this study are the high participation of residents and the reliability of the information provided by the anonymous nature of the surveys.

Finally, we consider that this information is valuable to gain a better understanding of various aspects related to the mental well-being and the educational environment of medical residents who, by taking care of themselves and living with greater well-being and quality of life, will have a better chance of taking care of the health of the society. This involves an update to the educational model, in harmony with ethics and with what society expects of a physician.

ConclusionsThis study of the educational environment in clinical and surgical postgraduate courses in Medellín using the PHEEM instrument, which explored educational environment and mental well-being, identified a positive correlation between these two determining aspects of medical training, implying that a better perception of the resident of the educational environment is correlated with a higher level of mental well-being.

Poorer mental well-being in this group was related to fatigue derived from the academic and healthcare burden. The aspects of the educational environment in which the residents identified a possibility for improvement were having time for non-academic activities and having frequent feedback, which includes strengths and weaknesses as well as counselling when failing. These identified areas, both susceptible to change, could be evaluated longitudinally to observe how they modify the perception of the educational environment and the mental well-being of residents.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.