The objective of this study was to explore the approach to patients with psychiatric symptoms by nursing professionals in general hospitalisation units in the city of Medellín, Colombia.

MethodsA qualitative study with the method of interpretive phenomenology. 11 nursing professionals from general hospitalisation units in the city of Medellín, Colombia participated. The information analysis was processed according to the Phenomenological Interpretive Analysis method and with the support of the NVIVO Plus 12 software.

ResultsThe nurses’ experience is described through three themes: representations of the patient with psychiatric symptoms, the patient as aggressive, violent and unpredictable; feeling fearful while providing care, caring for others in the midst of prevention, fear and stress, and being in a chaotic situation, a circumstance that gets out of control and alters the dynamics of the hospitalisation unit.

ConclusionsCaring for patients with psychiatric symptoms is stressful, especially when nursing professionals perceive a lack of support from other colleagues and from the hospital administration. The above favours the development of alterations in the professional's physical and mental health.

El objetivo del estudio es explorar cómo es el abordaje de los pacientes con síntomas psiquiátricos que hacen los profesionales de enfermería de unidades de hospitalización general de la ciudad de Medellín, Colombia.

MétodosEstudio cualitativo mediante el método de la fenomenología interpretativa. Se contó con la participación de 11 profesionales de enfermería de unidades de hospitalización general de la ciudad de Medellín, Colombia. El análisis de la información se hizo según el método de análisis interpretativo fenomenológico y con apoyo del software NVIVO Plus 12.

ResultadosLa experiencia que viven los enfermeros se describe a través de tres temas: representaciones del paciente con síntomas psiquiátricos, el paciente como agresivo, violento e impredecible; sentir miedo en la atención, cuidar en medio de la prevención, el temor y el estrés, y estar en una situación caótica, circunstancia que se sale de control y altera las dinámicas de la unidad de hospitalización.

ConclusionesEl cuidado los pacientes con síntomas psiquiátricos resulta estresante, en especial cuando se percibe falta de apoyo de otros compañeros y de la administración del hospital. Ello favorece la aparición de alteraciones de la salud física y mental del profesional.

Psychiatric symptoms regularly occur in patients hospitalised in institutions not specialised in mental health, even when they do not have a diagnosed underlying psychiatric condition.1 Around 5% of the cases entering Accident and Emergency units are associated with psychiatric causes.2 This situation has increased in recent years as a consequence of a number of different factors that contribute to the onset of psychiatric problems and illnesses, such as armed conflict, the inappropriate use of new technologies, or population growth, among others.3,4

For the World Health Organization (WHO), psychiatric disorders represent a public health problem, not only because of their impact on disability-adjusted life years, but because they lead to situations that are difficult to cope with for both families and the community. This may be because psychiatric symptoms often have negative associations due to the burden of stigma that falls on the people who are diagnosed.5

There is an increasingly greater demand for health services from people with depressive or psychotic symptoms, with episodes of mania or due to the use of psychoactive substances in general hospitals.6 However, not all people who suffer from these disorders have a medical psychiatric diagnosis. This means that, in hospitalisation units, the psychiatric symptoms manifested by the patient are confused with inappropriate behaviour.

Disorders that may involve psychiatric symptoms include those affecting the nervous and endocrine systems and the cardiovascular and respiratory systems.7 In some cases, aggressive behaviour, hallucinations and delirium may occur, with delirium being a common acute condition in hospitalised older people.8

Anxiety and depression, being among the most prevalent mental illnesses, can occur in a large number of hospitalised patients. These patients may become aggravated when receiving unexpected news, as a result of physical complications or because of distancing from their social and family circle deriving from the changes that led to their admission to hospital.9

The health services and other services that are in contact with people with psychiatric diagnoses are currently seeking to promote humane care in their practices and among their healthcare staff.10 Registered nurses play a very important role within the healthcare team, as they have the opportunity to perform different activities throughout the day that contribute to the humanisation, recovery and well-being of people who are hospitalised. These interventions include those that address the psycho-emotional aspect of patients, as well as their behaviours and attitudes. These behaviours and attitudes can become complex to care for as and when they become associated with psychiatric symptoms, which are often not expected in patients admitted to general hospitals.11

By means of this study, we aim to broaden the perspectives on the care of people with psychiatric symptoms, who are often stigmatised and discriminated against in health services not specialised in mental health.12 Our aim is therefore to explore how registered nurses from general hospitalisation units in the city of Medellín, Colombia, approach patients with psychiatric symptoms.

MethodsThe study was carried out according to the qualitative research approach13 and applying the method of interpretive phenomenology, considered appropriate to explore the senses and experiences that arise from the phenomenon under study because, as Castillo14 stated, its objective is to understand the skills, practices and day-to-day experiences of the human beings.

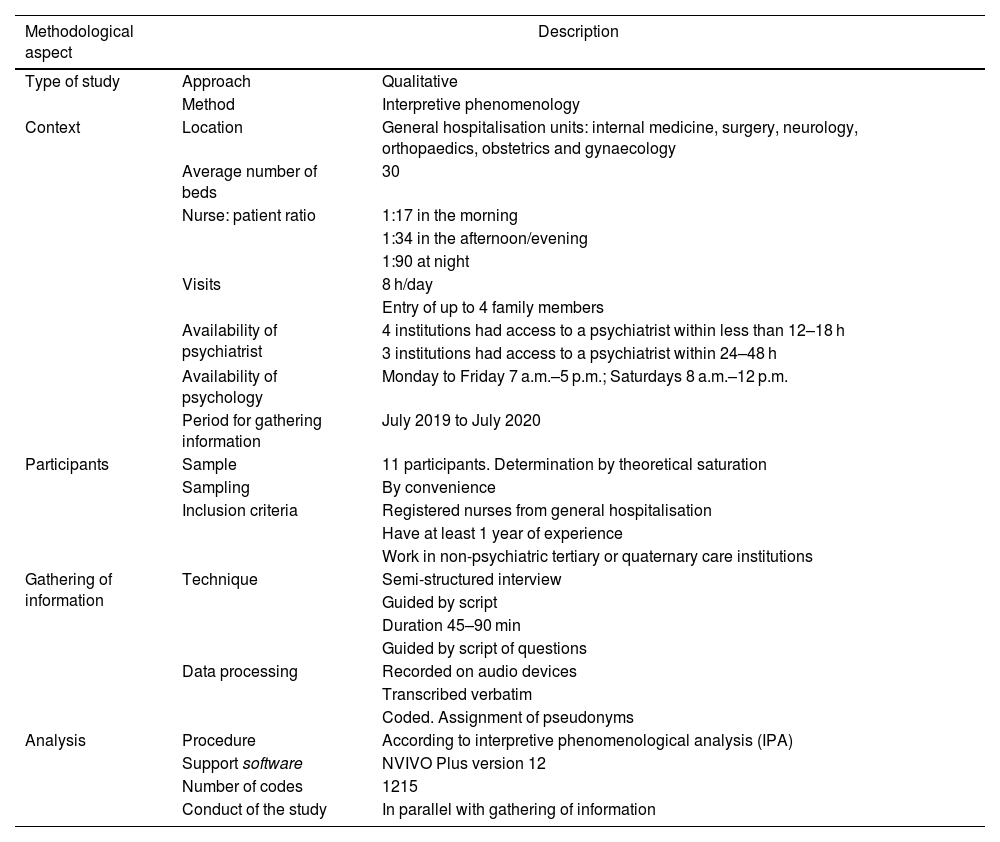

We included registered nurses from seven clinics in the city of Medellín, Colombia who worked in general hospitalisation units. The characteristics of the context in which the study took place as well as the main methodological aspects of the study are described in Table 1.

Methodological characteristics of the study.

| Methodological aspect | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of study | Approach | Qualitative |

| Method | Interpretive phenomenology | |

| Context | Location | General hospitalisation units: internal medicine, surgery, neurology, orthopaedics, obstetrics and gynaecology |

| Average number of beds | 30 | |

| Nurse: patient ratio | 1:17 in the morning | |

| 1:34 in the afternoon/evening | ||

| 1:90 at night | ||

| Visits | 8 h/day | |

| Entry of up to 4 family members | ||

| Availability of psychiatrist | 4 institutions had access to a psychiatrist within less than 12–18 h | |

| 3 institutions had access to a psychiatrist within 24–48 h | ||

| Availability of psychology | Monday to Friday 7 a.m.–5 p.m.; Saturdays 8 a.m.–12 p.m. | |

| Period for gathering information | July 2019 to July 2020 | |

| Participants | Sample | 11 participants. Determination by theoretical saturation |

| Sampling | By convenience | |

| Inclusion criteria | Registered nurses from general hospitalisation | |

| Have at least 1 year of experience | ||

| Work in non-psychiatric tertiary or quaternary care institutions | ||

| Gathering of information | Technique | Semi-structured interview |

| Guided by script | ||

| Duration 45–90 min | ||

| Guided by script of questions | ||

| Data processing | Recorded on audio devices | |

| Transcribed verbatim | ||

| Coded. Assignment of pseudonyms | ||

| Analysis | Procedure | According to interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) |

| Support software | NVIVO Plus version 12 | |

| Number of codes | 1215 | |

| Conduct of the study | In parallel with gathering of information | |

Of the seven institutions, four had a psychiatric department, making it more likely that patients requiring psychiatric care are assessed in a timely manner. Furthermore, all seven institutions had psychologists, although they required a referral from the treating physician to see the patient.

Information was gathered between July 2019 and July 2020 by means of a semi-structured interview. The search for participants was carried out by means of convenience sampling.15 The inclusion criteria were: registered nurses with at least one year’s experience working in general hospitalisation units of tertiary or quaternary level non-psychiatric health service providers. A general hospitalisation unit was considered to be one to which patients were admitted for monitoring and control by the following medical specialities: internal medicine, general surgery, neurology, orthopaedics, obstetrics and gynaecology.

A total of 11 registered nurses were interviewed, which was determined by the theoretical saturation of the themes. All the people invited to do so agreed to take part in the study. The interviews were conducted by members of the research team, who have academic training and experience in qualitative interviews. In addition to this, an exploratory study was conducted with the first two participants. The exploratory study consisted of assessing the type and clarity of the questions in the interview script and of conducting training for the approach to and performance of the subsequent interviews. Based on this study, adjustments were made to two of the questions in the script.

The interviews were conducted at a time and place agreed with the participants; eight interviews were held in classrooms at a university institution in order to provide a space free of interruptions and guarantee peace, quiet and privacy for the participants, and the other three interviews were held in doctor’s offices or offices at their workplaces after their work shift was over. Before starting the interview, participants were asked to sign the informed consent form.

The interviews were recorded and lasted approximately 45–90 min.

They were then transcribed verbatim in a word processor. During the interviews, a field diary was kept in which gestures and expressions, emotions, pauses and silences were recorded. These aspects were included in the transcription between parentheses to highlight non-verbal communication and make the transcription as close as possible to what was expressed by the participant. Pseudonyms were assigned when reference was made to persons, places or institutions. The interviews were coded with the acronym EE followed by the order number in which they were conducted.

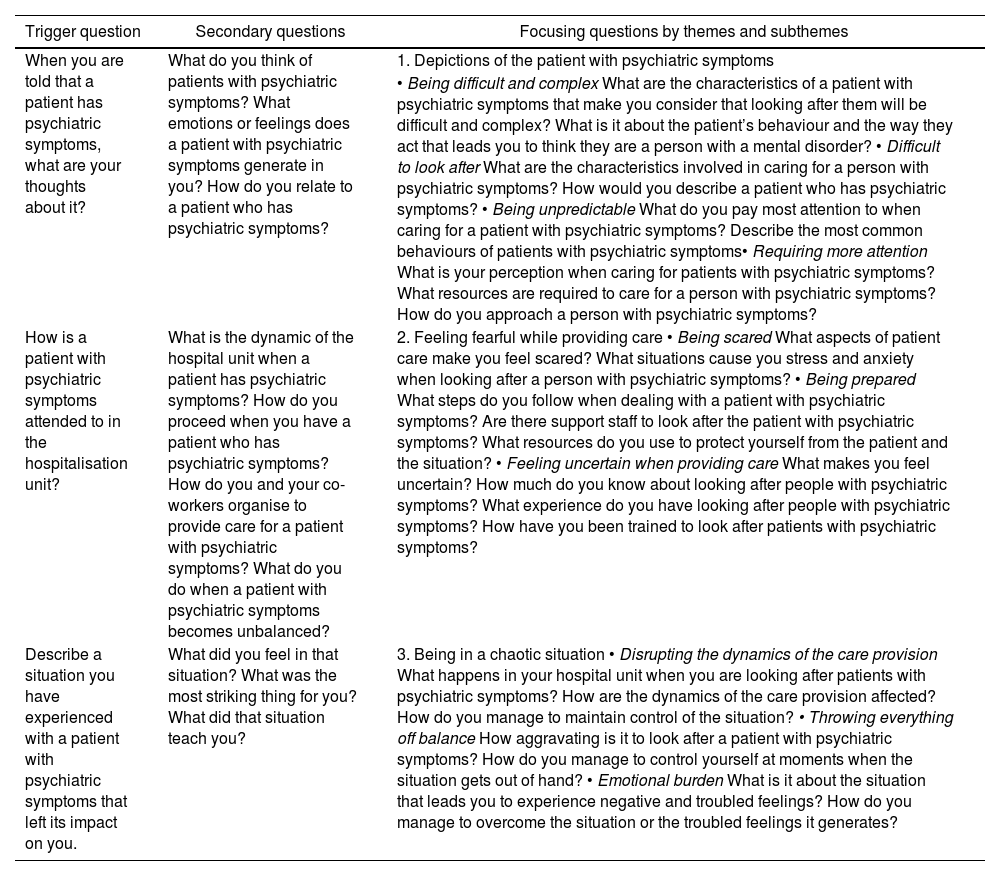

The interviews were conducted using open questions that served to initiate the conversation. In all the interviews, when the first trigger question was posed, the participants reacted with gestures of displeasure, surprise or bewilderment. In addition, emotions such as fear, anxiety and uncertainty predominated during the interviews, especially when the participant was asked to recall experiences related to the manifestation of psychiatric symptoms.

As the interview progressed, additional questions were asked in order to delve deeper into the subject. Also, to obtain information that would allow theoretical saturation, specific questions were asked and focussed on using themes and subthemes (Table 2). Other than the responses given by the participants, they did not express any additional questions or comments.

Script of questions.

| Trigger question | Secondary questions | Focusing questions by themes and subthemes |

|---|---|---|

| When you are told that a patient has psychiatric symptoms, what are your thoughts about it? | What do you think of patients with psychiatric symptoms? What emotions or feelings does a patient with psychiatric symptoms generate in you? How do you relate to a patient who has psychiatric symptoms? | 1. Depictions of the patient with psychiatric symptoms |

| • Being difficult and complex What are the characteristics of a patient with psychiatric symptoms that make you consider that looking after them will be difficult and complex? What is it about the patient’s behaviour and the way they act that leads you to think they are a person with a mental disorder? • Difficult to look after What are the characteristics involved in caring for a person with psychiatric symptoms? How would you describe a patient who has psychiatric symptoms? • Being unpredictable What do you pay most attention to when caring for a patient with psychiatric symptoms? Describe the most common behaviours of patients with psychiatric symptoms• Requiring more attention What is your perception when caring for patients with psychiatric symptoms? What resources are required to care for a person with psychiatric symptoms? How do you approach a person with psychiatric symptoms? | ||

| How is a patient with psychiatric symptoms attended to in the hospitalisation unit? | What is the dynamic of the hospital unit when a patient has psychiatric symptoms? How do you proceed when you have a patient who has psychiatric symptoms? How do you and your co-workers organise to provide care for a patient with psychiatric symptoms? What do you do when a patient with psychiatric symptoms becomes unbalanced? | 2. Feeling fearful while providing care • Being scared What aspects of patient care make you feel scared? What situations cause you stress and anxiety when looking after a person with psychiatric symptoms? • Being prepared What steps do you follow when dealing with a patient with psychiatric symptoms? Are there support staff to look after the patient with psychiatric symptoms? What resources do you use to protect yourself from the patient and the situation? • Feeling uncertain when providing care What makes you feel uncertain? How much do you know about looking after people with psychiatric symptoms? What experience do you have looking after people with psychiatric symptoms? How have you been trained to look after patients with psychiatric symptoms? |

| Describe a situation you have experienced with a patient with psychiatric symptoms that left its impact on you. | What did you feel in that situation? What was the most striking thing for you? What did that situation teach you? | 3. Being in a chaotic situation • Disrupting the dynamics of the care provision What happens in your hospital unit when you are looking after patients with psychiatric symptoms? How are the dynamics of the care provision affected? How do you manage to maintain control of the situation? • Throwing everything off balance How aggravating is it to look after a patient with psychiatric symptoms? How do you manage to control yourself at moments when the situation gets out of hand? • Emotional burden What is it about the situation that leads you to experience negative and troubled feelings? How do you manage to overcome the situation or the troubled feelings it generates? |

The data analysis was carried out by applying interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA),16 which aims to understand how people give meaning to their experiences by means of a detailed description of particular experiences as they are lived and understood by a person.17 The data analysis was performed in parallel with the gathering of information and with the support of NVIVO Plus software version 12.

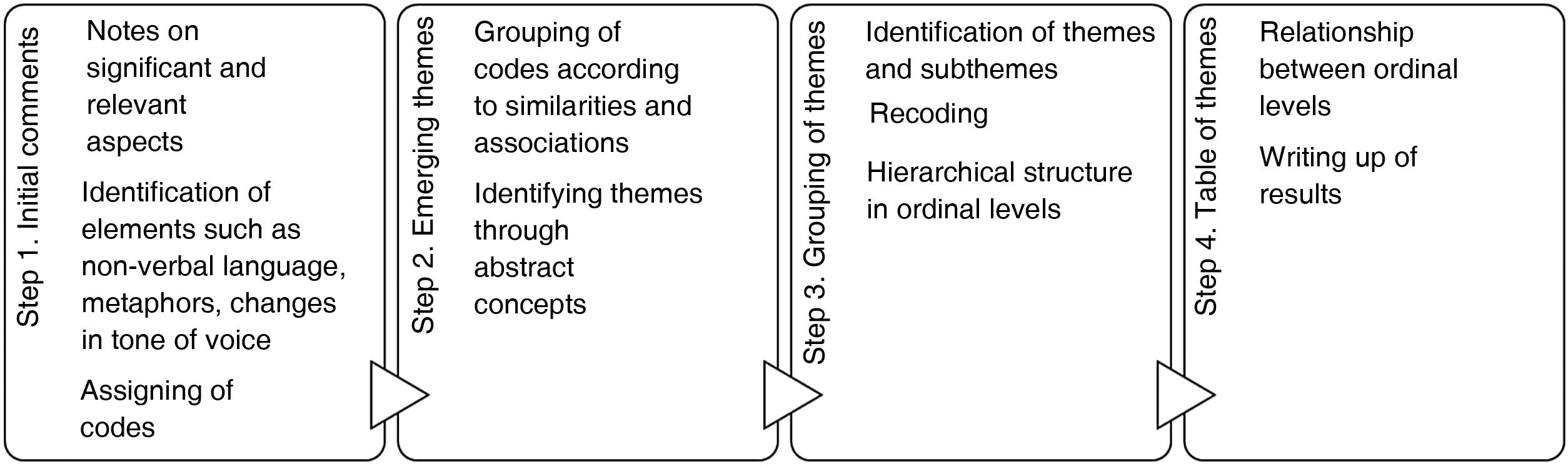

According to the IPA, it was performed in four steps (Fig. 1). In the first step, the interviews were read and reread two to three times. Upon each reading, the investigators took notes on aspects they found interesting and significant. To do this, the participants’ emotional responses, their non-verbal language, pauses and metaphors, among other things, were taken into account. Based on this, codes were assigned to represent the experiences reported by the participants. In the second step, similarities between the assigned codes were established that allowed themes to be identified. In the third step, the themes were grouped and a hierarchical structure of themes and subthemes was established. In the fourth step, relationships were established between the ordinal levels of the structure of analysis. The above was supported by theoretical and analytical memos and the creation of diagrams.

The study was submitted to and approved by the independent ethics committee for research in health of a university institution in Medellín, Colombia. The study was considered to be of minimal risk, so informed consent was requested. During the conduct of the study, none of the participants presented with any emotional or psychological disorders, and nor did they show discomfort with the interview or the subject matter addressed in the study.

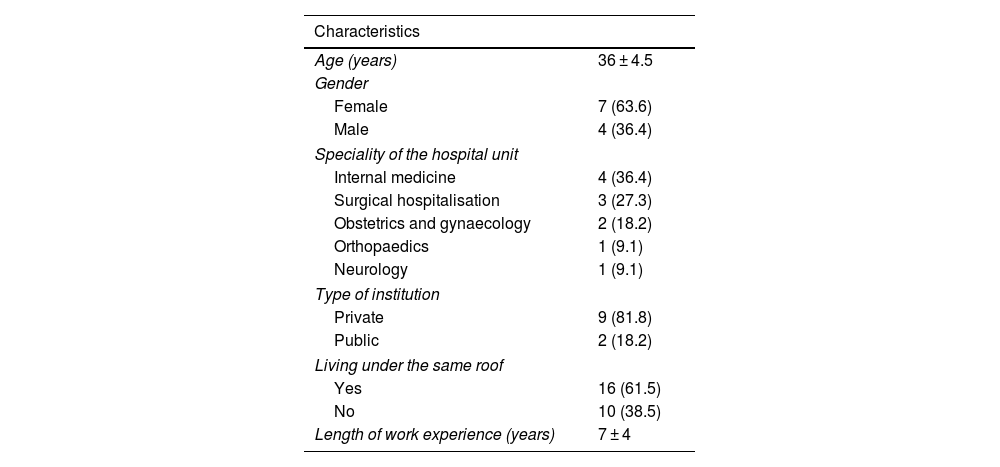

Conduct of the study11 registered nurses participated in the study. Their average age was 36 years. Seven were women. At the time of the interviews, four worked in internal medicine hospital units, three in surgical admissions, and the rest in orthopaedic and neurology units. Most of the participants worked in private institutions and the average length of work experience was seven years. None of the participants had academic training or experience in caring for patients with psychiatric disorders (Table 3).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants (n = 11).

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 36 ± 4.5 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 7 (63.6) |

| Male | 4 (36.4) |

| Speciality of the hospital unit | |

| Internal medicine | 4 (36.4) |

| Surgical hospitalisation | 3 (27.3) |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | 2 (18.2) |

| Orthopaedics | 1 (9.1) |

| Neurology | 1 (9.1) |

| Type of institution | |

| Private | 9 (81.8) |

| Public | 2 (18.2) |

| Living under the same roof | |

| Yes | 16 (61.5) |

| No | 10 (38.5) |

| Length of work experience (years) | 7 ± 4 |

The values are expressed as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

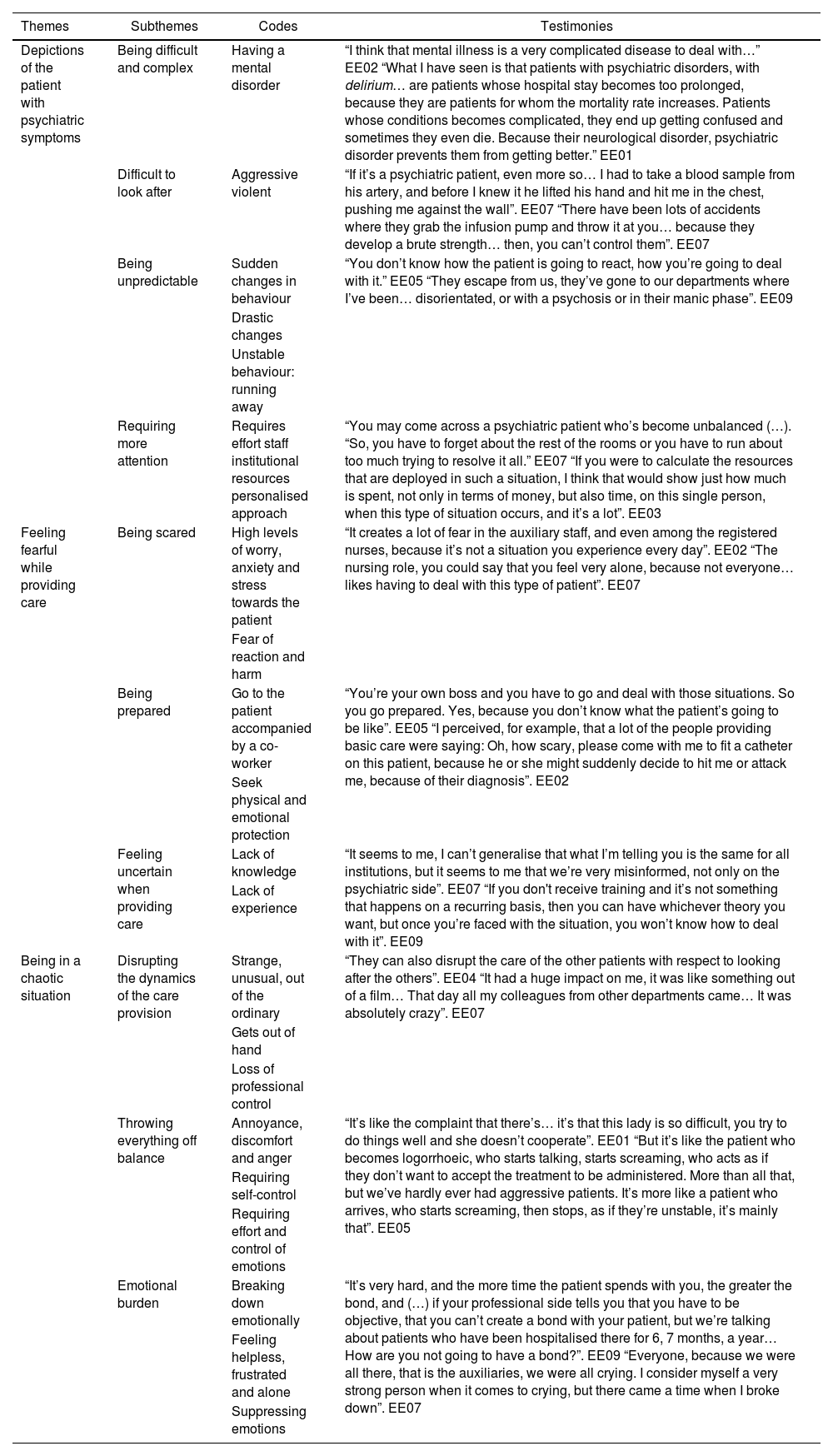

The experience of the nurses when caring for people with psychiatric symptoms in general hospitalisation units is described by means of three themes, these being: depictions of the patient with psychiatric symptoms; feeling fearful while providing care; and being in a chaotic situation. Table 4 shows the analysis matrix with the themes and subthemes and a summary of the codes and accounts that represent them.

Analysis matrix.

| Themes | Subthemes | Codes | Testimonies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depictions of the patient with psychiatric symptoms | Being difficult and complex | Having a mental disorder | “I think that mental illness is a very complicated disease to deal with…” EE02 “What I have seen is that patients with psychiatric disorders, with delirium… are patients whose hospital stay becomes too prolonged, because they are patients for whom the mortality rate increases. Patients whose conditions becomes complicated, they end up getting confused and sometimes they even die. Because their neurological disorder, psychiatric disorder prevents them from getting better.” EE01 |

| Difficult to look after | Aggressive violent | “If it’s a psychiatric patient, even more so… I had to take a blood sample from his artery, and before I knew it he lifted his hand and hit me in the chest, pushing me against the wall”. EE07 “There have been lots of accidents where they grab the infusion pump and throw it at you… because they develop a brute strength… then, you can’t control them”. EE07 | |

| Being unpredictable | Sudden changes in behaviour | “You don’t know how the patient is going to react, how you’re going to deal with it.” EE05 “They escape from us, they’ve gone to our departments where I’ve been… disorientated, or with a psychosis or in their manic phase”. EE09 | |

| Drastic changes | |||

| Unstable behaviour: running away | |||

| Requiring more attention | Requires effort staff institutional resources personalised approach | “You may come across a psychiatric patient who’s become unbalanced (…). “So, you have to forget about the rest of the rooms or you have to run about too much trying to resolve it all.” EE07 “If you were to calculate the resources that are deployed in such a situation, I think that would show just how much is spent, not only in terms of money, but also time, on this single person, when this type of situation occurs, and it’s a lot”. EE03 | |

| Feeling fearful while providing care | Being scared | High levels of worry, anxiety and stress towards the patient | “It creates a lot of fear in the auxiliary staff, and even among the registered nurses, because it’s not a situation you experience every day”. EE02 “The nursing role, you could say that you feel very alone, because not everyone… likes having to deal with this type of patient”. EE07 |

| Fear of reaction and harm | |||

| Being prepared | Go to the patient accompanied by a co-worker | “You’re your own boss and you have to go and deal with those situations. So you go prepared. Yes, because you don’t know what the patient’s going to be like”. EE05 “I perceived, for example, that a lot of the people providing basic care were saying: Oh, how scary, please come with me to fit a catheter on this patient, because he or she might suddenly decide to hit me or attack me, because of their diagnosis”. EE02 | |

| Seek physical and emotional protection | |||

| Feeling uncertain when providing care | Lack of knowledge | “It seems to me, I can’t generalise that what I’m telling you is the same for all institutions, but it seems to me that we’re very misinformed, not only on the psychiatric side”. EE07 “If you don't receive training and it’s not something that happens on a recurring basis, then you can have whichever theory you want, but once you’re faced with the situation, you won’t know how to deal with it”. EE09 | |

| Lack of experience | |||

| Being in a chaotic situation | Disrupting the dynamics of the care provision | Strange, unusual, out of the ordinary | “They can also disrupt the care of the other patients with respect to looking after the others”. EE04 “It had a huge impact on me, it was like something out of a film… That day all my colleagues from other departments came… It was absolutely crazy”. EE07 |

| Gets out of hand | |||

| Loss of professional control | |||

| Throwing everything off balance | Annoyance, discomfort and anger | “It’s like the complaint that there’s… it’s that this lady is so difficult, you try to do things well and she doesn’t cooperate”. EE01 “But it’s like the patient who becomes logorrhoeic, who starts talking, starts screaming, who acts as if they don’t want to accept the treatment to be administered. More than all that, but we’ve hardly ever had aggressive patients. It’s more like a patient who arrives, who starts screaming, then stops, as if they’re unstable, it’s mainly that”. EE05 | |

| Requiring self-control | |||

| Requiring effort and control of emotions | |||

| Emotional burden | Breaking down emotionally | “It’s very hard, and the more time the patient spends with you, the greater the bond, and (…) if your professional side tells you that you have to be objective, that you can’t create a bond with your patient, but we’re talking about patients who have been hospitalised there for 6, 7 months, a year… How are you not going to have a bond?”. EE09 “Everyone, because we were all there, that is the auxiliaries, we were all crying. I consider myself a very strong person when it comes to crying, but there came a time when I broke down”. EE07 | |

| Feeling helpless, frustrated and alone | |||

| Suppressing emotions |

From the data, we identified that the participants generalise and consider the patient with psychiatric symptoms as someone who suffers from a mental disorder. This predisposes their treatment to be perceived as difficult and complex, as can be seen in the following account: “in hospitalisation… I think that psychiatric patients… have been difficult.” EE05.

The registered nurse considers the patient with psychiatric symptoms as someone who is difficult to look after, which is associated with the depiction of the patient as someone aggressive, violent and unpredictable: “(…) How do I approach them?”, or “How is the patient going to react to my approach? I find it very complicated and difficult to deal with patients with these symptoms”. EE05.

They also see the patients as people who break from the ordinary routine and rapidly modify their way of acting, because the changes they suffer are drastic and immediate and they behave in an unstable manner to the point that at any moment they may run away or “lash out and hit”: “just a minute ago he was fine and now look at him, we have to call his family… to call his aunt, who'd already called us and we'd told her he was fine, now we have to tell her… he went really downhill and died.” EE07.

The participants recognise that these patients need and demand greater attention, time and effort from the institution’s staff and resources. Therefore, they require a personalised approach: “having these patients involves providing more care, more staff who will focus on this patient… Often they are focussing on this patient to organise them, so the care for the other patients… what happens there?”. EE04. This situation requires greater effort from the registered nurse, who has to guarantee sufficient and timely care for the patient without ceasing to provide care to the other patients under their care during their work shift.

Feeling fearful while providing careThe data identify a feeling of fear that manifests itself when providing care to a patient with psychiatric symptoms: “it scares me a lot, I mean, what I really feel with respect to patients with disorders, with a mental disorder is fear…” EE08.

Fear is an emotion that is perceived in the midst of situations that generate high levels of worry, anxiety and stress. This feeling is attributed to the patient’s behaviour and can even lead to not wanting to approach them: “with my fellow nurses, with my auxiliary nurses it’s like that, the same stress that I feel, that it generates in me, is generated in them… There are some who get more anxious, there are some who cry or tell me: boss, I can’t do it; boss, I’m scared”. EE07.

We identified that the fear of the patient is associated with two aspects. On the one hand, fear of the patient’s reaction and the possibility of aggression and causing physical harm: “I think that the first fear is that, fear of being attacked, of being hurt whilst providing healthcare”. EE02.

On the other hand, there is a feeling of uncertainty that is associated with the lack of knowledge and experience in caring for a person who has some disturbance or disorder in their mental health: “I had no experience with psychiatric patients. So, of course, being a new experience, it creates uncertainty… what will happen?”. EE09.

Fear seems to permeate the care; thus, when the nurse goes to attend to the patient, he or she appears cautious and fearful: “but what I always reflect is fear towards these patients”. EE04.

In this situation, the staff feel the need to be accompanied by other colleagues, which leads to the patient being approached in a group as a mechanism of strength and protection: “many of the people who are offering basic care said: oh, how scary! Please come with me to fit a catheter on this patient”. EE02.

Being in a chaotic situationCaring for a patient with psychiatric symptoms takes place in the midst of a chaotic situation. This situation is characterised by being strange, unusual and out of the ordinary, getting out of hand and beyond the control of the nursing staff, with the patient taking control of the moment and the situation, doing what he or she wants and putting the safety and tranquillity of both the staff and the hospital unit at risk: “that man was throwing everything, breaking doors, he damaged the bed, he went crazy, he picked up faeces and threw them all over the room, and then (…), that was horrible because it was like a horror film. We were all wearing gowns, gloves, masks, we called security… They arrived and he pushed the security people out of the way, that was horrible”. EE07.

In this regard, the participants consider that the hospitalisation unit is not adequate for the care and attention of these patients. In some cases, the attitude of the patients generates annoyance, discomfort, even anger and rage in the nurse, requiring him or her to exercise self-control and make an effort to remain calm and avoid confrontation and aggression with the patient: “I didn’t feel in a position at that time to perform the tests on the patient because of the attitude he had towards me (…). I simply didn’t go back into the room, in order to avoid an encounter with him”. EE01.

The impact and complexity of the situation can lead to a point where the nurse breaks down and emotionally collapses: “I had to sit down and I was crying, the only thing I did was drink water, I didn’t have breakfast, I didn’t have lunch, I didn’t have anything to drink (…) and I came home crying”. EE07.

In addition to the above, they may feel helpless, frustrated and alone, especially when they feel that they cannot help and they do not know what to do to improve the patient’s situation. These emotions are often suppressed in an attempt to act professionally and seek the patient’s well-being: “at first you feel sorry for the patient, because you can see that he or she is desperate, but then I say that this is where you have to start thinking that you are doing these things for the good of the patient”. EE05.

DiscussionThe depictions and social imagery of the healthcare professionals are associated with the characteristics of the symptoms of patients with mental illnesses, such as aggression, violence, disorientation and functional impairment.11 The stereotypes built based on this are determining factors in creating the stigma that promotes discrimination and rejection towards people with psychiatric illnesses.18

In line with our investigation, Gil et al.19 found that healthcare professionals perceived patients with psychiatric symptoms as unpredictable, difficult to manage and, in most cases, violent. It has also been found that the nurses who frequently care for patients with psychiatric disorders consider that violent episodes related to patient care are inevitable, and even become accustomed to them and recognise that they themselves can trigger conflict with the patient.20 This contrasts with our results, according to which nurses are fearful and uncertain while providing the care.

According to the healthcare professionals in general hospitals, there is a strong association between the level of danger that a patient is perceived to pose and their psychiatric diagnosis.21,22 These beliefs tend to affect the quality of care, as healthcare workers seek to minimise contact and interventions with people suffering from a psychiatric disorder.23

As for the feeling of being in a chaotic situation, Fajardo-Ortiz et al.24 explain that chaos is a situation that occurs when changes occur in parts of the system that can lead to “complicated situations or unexpected outcomes”. They suggest, similar to our findings, that one of the aspects that arises during a chaotic situation is uncertainty and the fear of sudden and unexpected changes in the patient. Balandier25 also considers that a chaotic situation is characterised by the disruption of a preconceived process or situation. This practice fuels the fear of social violence and the manifestation of collective reproach against people who do not respect the rules, as is the case for patients with psychiatric symptoms who, in the midst of their crises, may exhibit aggressive behaviour.

Regarding the feeling of fear or dread towards patients with psychiatric symptoms, Oldham et al.26 identified, just like our study, that nurses display apprehension when they perceive that the patients admitted to the hospitalisation unit have, for the most part, psychiatric disorders or mental health conditions. The nurses express a variety of concerns about caring for patients with challenging or dangerous and unpredictable behaviour.27

Furthermore, Masa’Deh et al.28 and Piñelo et al.29 identified that those nurses who work in hospital settings where patients with psychiatric disorders are attended to have higher rates of emotional impact and stress. Aspects such as the aggressive and violent behaviour of patients, increased workload and lack of training are related to this emotional state. Added to this is the fact that, as reported by Ramacciati et al.,20 nurses often feel vulnerable, unsupported, alone and abandoned, as while providing care to the patients, and especially when they have difficulties, they find nobody in the hospital coordination or management to talk to or support them during the crises.

Aspects such as those mentioned above can affect the efficiency and capacity of nursing staff to provide quality care to patients with psychiatric disorders,28 as the inability to cope with and manage the difficult situations that arise can affect their general health.30 Wang et al.31 recognised that work-related stress when caring for patients with psychiatric disorders is related to the level of depression they may subsequently develop. When nurses feel stressed at work, they have lower physical and psychological response levels for coping with it.

Pileño et al.29 suggest that it is necessary to prepare healthcare workers for distress and anxiety, in order to improve their own health and prevent the quality of patient care from being compromised. This is particularly important as nurses may suffer emotional and operational problems and difficulties if they start to work in a psychiatric unit without prior training.

ConclusionsOur study concludes that nursing staff in hospitalisation units depict patients with psychiatric symptoms as complex, aggressive and unpredictable. This contributes to the care process taking place amidst feelings of fear and uncertainty and the situation being depicted as chaotic. Moreover, caring for these patients is stressful, especially when there is a perceived lack of support from other colleagues and from the hospital administration. This can lead to negative impacts on the physical and mental health of the nursing staff.

Our recommendation is that studies should be conducted on the coping strategies used by nursing staff to manage the complex situations that arise when caring for patients with psychiatric symptoms. We would also encourage the hospital units to develop support programmes for nursing staff, aimed at setting up interdisciplinary support networks for the care of patients with psychiatric symptoms, and to implement or strengthen emotional response teams for healthcare professionals working in general hospitalisation.

FundingThis work was funded by the Dirección de Investigación e Innovación (CIDI) [Directorate for Research and Innovation] of the Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana (project: 179C-06/18-38) in Medellín, Colombia. The CIDI did not participate in the design of the study or in the collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, nor did it interfere in the writing of the article or in the decision to send it for publication.

Author contributionsDaniel Ricardo Zaraza-Morales: project design, gathering of information, writing up of the research, approval of the final review of the manuscript and submission to the journal. Camilo Duque-Ortiz: project design, gathering of information, writing up of the research, and approval of the final review of the manuscript. Hellen Lucia Castañeda-Palacio: project design, preparation, gathering of information and approval of the final review of the manuscript. Liliana María Hinestrosa Montoya: project design, gathering of information and approval of the final review of the manuscript. Maria Isabel Chica Chica: project design, gathering of information and approval of the final review of the manuscript. Lina Marcela Hernández Sánchez: project design, gathering of information and approval of the final review of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestNone.

We would like to thank all the nursing staff who participated in our investigation and who, with their valuable stories, helped us to construct this wonderful final product.