The conceptualization of suicidal behavior is very complex and constitutes a worldwide health problem. Its etiology is multifactorial and in many cases preventable. Suicide and neurodegenerative disease have some risk factors in common, such as depression, feelings of hopelessness and social isolation.

ObjectiveTo find out if patients with Parkinson's disease (PD), multiple sclerosis (MS), Alzheimer's disease (AD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Huntington's disease (HD) are more likely to present suicidal behavior than the general population and to ascertain the most relevant risk factors.

MethodA review of scientific articles in databases was carried out, as well as of protocols and documents published on national and government websites linking neurodegenerative disease and suicide.

ResultsA clear relationship was found between suicide and MS, ALS and HD. Results in relation to PD and AD are somewhat contradictory but a series of risk factors were detected, the presence of which could predispose individuals to this behavior.

ConclusionsThere is a greater risk of suicidal behavior in patients with MS, ALS and HD. A series of relevant risk factors associated with this behavior were found, knowledge of which will help us to detect warning signs and take early action.

La conceptualización de la conducta suicida es muy compleja y constituye un problema de salud mundial. Su etiología es multifactorial y, en muchos casos, prevenible. Suicidio y enfermedad neurodegenerativa coinciden en algunos factores de riesgo como la depresión, los sentimientos de desesperanza y el aislamiento social.

ObjetivoConocer si los pacientes con enfermedad de Parkinson (EP), esclerosis múltiple (EM), enfermedad de Alzheimer (EA), esclerosis lateral amiotrófica (ELA) y enfermedad de Huntington (EH) están más expuestos a presentar conducta suicida y cuáles son los factores de riesgo más relevantes.

MétodoSe realiza una revisión bibliográfica de artículos científicos en bases de datos, así como protocolos y documentos de sitios web nacionales y gubernamentales relacionando la enfermedad neurodegenerativa y el suicidio.

ResultadosSe ha encontrado una clara relación entre suicidio y EM, ELA y EH, mientras que los resultados en EP y EA son bastante contradictorios, si bien se ha detectado una serie de factores de riesgo cuya presencia puede predisponer a este comportamiento.

ConclusionesExiste mayor riesgo de conducta suicida en pacientes con EM, ELA y EH y a su vez se han encontrado una serie de factores de riesgo relevantes asociados a dicha conducta cuyo conocimiento nos ayuda a detectar signos de alarma y a actuar precozmente.

Suicide is a worldwide health problem, with approximately a million annual deaths globally.1 In Spain it is the first non-natural cause of death, above traffic accidents,2 reaching 1% of the total deaths registered.3 Reported suicide data is considered to be underestimated, given that it is sometimes hard to distinguish between violent or accidental loss of life and deaths that were intentionally caused. This uncertainty is stronger in the case of chronic diseases, in which the suicide might have occurred through taking the normal prescribed drugs in a smaller or larger dose.

Likewise, it is hard to obtain data on the incidence of suicide attempts. This information is generally calculated by taking the cases registered in emergency services in an area and extrapolating from that. Various sources indicate that, for each adult that commits suicide, another 20 possibly made a suicide attempt.4 A European-level study also found that, for Spain, the prevalence of suicidal ideation was 4.4% and 1.48% for suicide attempts.5

The conceptualisation of suicide is complex. In Spain, the Clinical Practice Guidelines on Prevention and Treatment of Suicidal Behaviour published by the Ministry of Health uses the nomenclature and classification established by Silverman et al.1 in 2007. In this system, they distinguish between suicidal ideation, suicidal communication (suicidal threat or plan) and suicidal behaviour (attempted or completed suicide).

Suicide is a major, enormously complex problem, but it is often preventable. Self-esteem, coping strategies and strong social-family support, as well as proper treatment for mental disorders and substance abuse, are considered protective factors against suicidal ideation.1

The aetiology of suicide lies in many factors. The more risk factors there are, the greater the risk; although some of those elements have enough specific weight to lead to the suicide.1 These risk factors include the following1,2: being male, being of an age ranging either from 50 to 59 years old or from 70 to 89 years old, being single, and having economic problems, little social support and a lack of religious beliefs. An important role is played by mental disorders, desperation, impulsiveness, substance abuse, previous suicidal behaviour and physical or sexual abuse during childhood.1 Media exposure is also associated, stemming from what is called the “copy-cat effect”.6

Various neurological structures might be related to suicidal behaviour.7 The tonsil, the lateral septal nucleus and the hippocampus are structures that participate in cognition and behaviour control. Any neurological disease that involves these structures can increase the risk of suicide. Serotoninergic transmission is also lowered in individuals that have made suicide attempts and researchers have found a polygenic inheritance that would affect serotonin biosynthesis.7

Various protective factors reduce the likelihood of suicide. Examples of these factors are having confidence in oneself, skills in social relationships and conflict resolution, strong social-family support and religious beliefs; proper treatment of mental disorders and substance abuse is also positive. In women, having children is considered a protective factor.8

Some of the risk factors for suicidal behaviour coincide with the idiosyncrasies of neurodegenerative diseases. These diseases include9: Parkinson’s disease (PD), Multiple sclerosis (MS), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Huntington’s disease (HD).

The aim of our study was to ascertain whether patients with the neurodegenerative diseases mentioned above are at greater risk for suicidal behaviour compared with the general population and to determine the most relevant risk factors for these diseases.

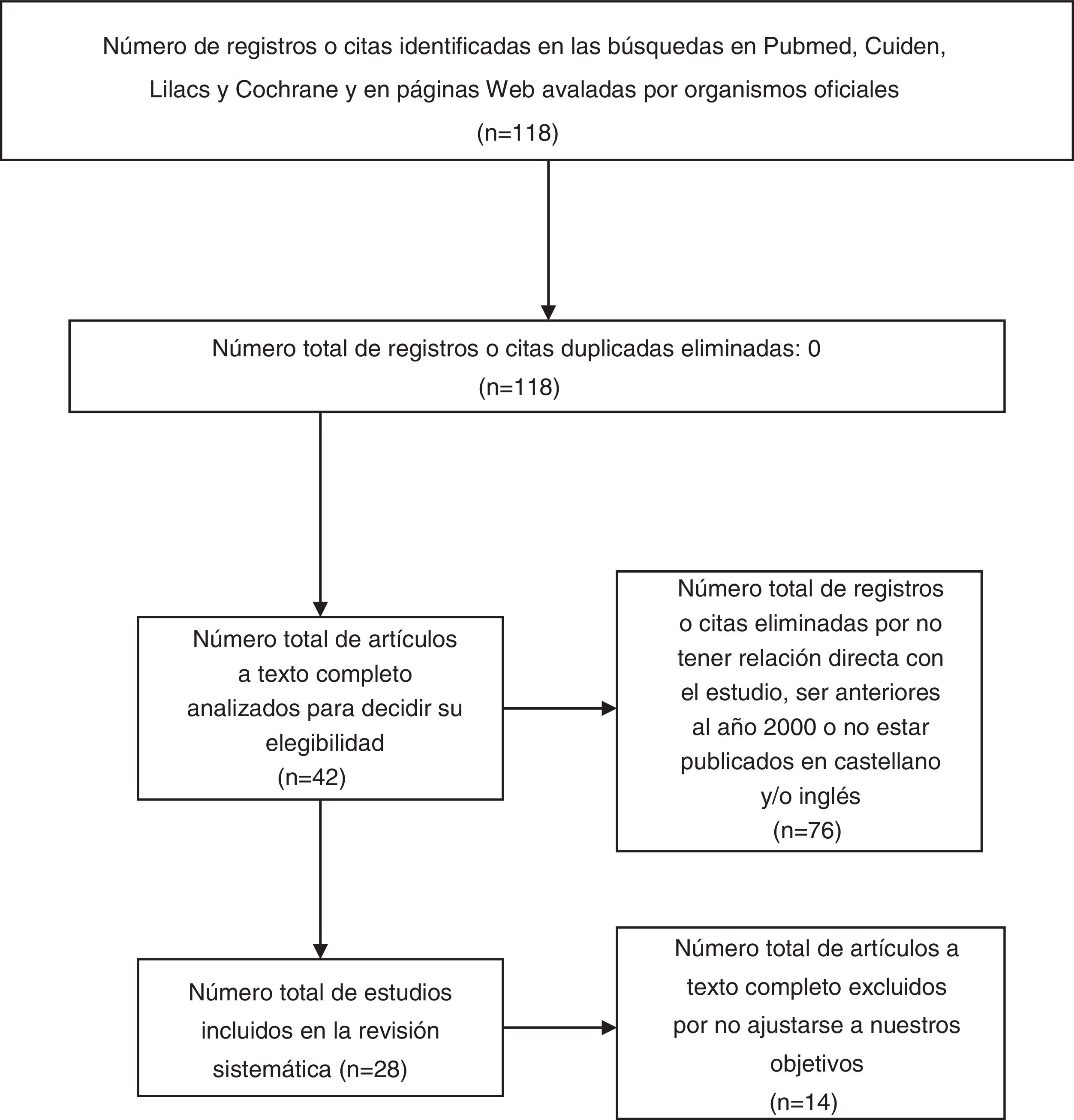

MethodIn July 2019, we used database searches as our main tool to prepare a reference review analysis. First, we converted the natural terms to those in the thesauruses in the internet portal of the Spanish Virtual Health Library (Biblioteca Virtual en Salud España). The PubMed, Cuiden, LILACS and Cochrane databases were then accessed through the Virtual Library Metasearch Engine of the Community of Madrid’s Public Healthcare System. We used the following MeSH terms: neurodegenerative diseases, Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, Huntington disease and suicide. The database search strategies included the Boolean operator “AND” to combine the MeSH terms (neurodegenerative diseases “AND” suicide; Alzheimer's disease “AND” suicide…). Criteria for inclusion of the articles were a publishing date from the year 2000 or later, with an abstract/summary and complete text in Spanish and/or English, with clear definitions and specific conclusions. We performed a methodological critical evaluation on the articles included, eliminating the articles that were of little relevance for our study or that did not apply to our objectives. The exclusion criteria consisted of being an opinion article with little or no scientific evidence, not having a direct relationship with our objective or not fulfilling the criteria of inclusion. Texts edited in paper and additional protocols were also consulted using national and governmental websites (Fig. 1).

ResultsParkinson’s disease (PD)Many of the known risk factors for suicide are prevalent in patients with PD.10 In spite of the existence of these factors, there is little agreement on the association between suicide and PD. Some of the studies reviewed suggested a high risk,11,12 while in contrast, other studies found a lower risk13 (Table 1).

Summary of studies related to Parkinson’s disease (PD).

| Title | Author/year | Country | Population/design | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide in Parkinson's Disease | Li et al.,10 2018 | Singapore | Follow-up of a cohort of 2012 subjects with PD for 11 years. Cases consisted of 11 patients that committed suicide and controls were 30 subjects with PD that died from other causes | - The patients that committed suicide were younger, had fewer comorbidities, better cognition and more pronounced ON/OFF periods |

| Increased suicide risk and clinical correlates of suicide among patients with Parkinson's disease | Lee et al.,12 2016 | Korea | Follow-up of 4362 subjects with PD for 6 years. | - Suicide rate 2 times higher than that of the general population |

| Retrospective case-control study, correlating variables (29 patients with PD that committed suicide compared with 116 controls that did not commit suicide) | - Statistically-significant association for suicide in: male sex, commencement of motor symptoms in limbs, history of depression, delirium, psychiatric disorders and high L-dopa dose | |||

| Suicide and suicidal ideation in Parkinson's disease | Kostic et al.,11 2010 | Serbia | Follow-up of a cohort of 102 individuals with Parkinson’s disease for 8 years | - Specific mortality from suicide 5.3 higher than that expected in the general population |

| Neuropsychological and psychiatric battery on 128 patients with Parkinson’s disease | - 22.7% of the patients had suicidal ideation | |||

| Parkinson's disease and suicide: a profile of suicide victims with Parkinson's disease in a population‐based study during the years 1988–2002 in Northern Finland | Mainio et al.,15 2009 | Finland | Suicides in individuals aged 50 years or older during a period of 14 years in the province of Oulu in Finland (n = 555) | - Suicide occurred in 1.6% of the patients with PD. |

| Risk factors found: male subject with a recently-diagnosed disease, that lived in a rural area, had multiple physical diseases and had attempted suicide previously | ||||

| Are patients with Parkinson's disease suicidal? | Myslobodsky et al.,13 2001 | USA | In the registry of the National Health Statistics Centre, for the period from 1991 to 1996, deaths from suicide were compared between the patients with a diagnosis of PD and the general population | - A rate 10 times higher was found in the general population |

Several researchers have studied the profiles of patients with PD that have committed suicide, identifying various risk factors. In terms of social and demographic profile, suicide victims with PD are older than the general population, but they are younger than patients with PD that die from other causes.10,14 Male patients revealed greater risk of suicide12,15 and individuals living in rural areas have shown an association with this risk.15 There is a statistically-significant association between suicide and the history of any mental illness in these patients; depression is strongly associated,12,14 as are previous suicide attempts.15 Greater risk has been registered in recently-diagnosed patients,15 along with having fewer medical comorbidities than individuals that die from other causes.14 Patients with PD that committed suicide had better motor function, but they also had more frequent motor fluctuations (ON/OF), which often occurs in younger patients (this fact might drive these relatively young patients in good cognitive status with few comorbidities to commit suicide).10 These results suggest that motor fluctuations rather than the severity of the disease strongly contribute to suicide. As for treatment with levodopa, there is no consensus on the role that this drug plays in suicide. Various studies reported that there were cases of suicide shortly after beginning treatment with levodopa, but other later studies have been less consistent.14

Multiple sclerosis (MS)The various studies that have evaluated the risk of suicide in patients with MS have found a higher risk compared with the general population. The studies also found greater suicidal ideation, suicide attempts and completed suicide16–18 (Table 2).

Summary of studies related to multiple sclerosis (MS).

| Title | Author/year | Country | Population/design | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal ideation, anxiety and depression in patients with multiple sclerosis. | Tauil et al.,16 2018 | Brazil | 132 patients with relapsing-remitting MS were evaluated using the Expanded Disability Status Scale, the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II), the Beck Suicidal Ideation scale (BSI) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression and Scale | High prevalence of anxiety and depression and a greater suicidal ideation rate in comparison with the general population were found |

| Risk factors or suicide in multiple sclerosis: a case-control study. | Cerqueira et al.,18 2015 | Brazil | The study included 60 patients with MS; this group was compared by sex and age with a control group | Risk of suicide in 16.6% of the participants. 8.3% had attempted suicide in the past, and 8.3% were currently at risk for suicide |

| Suicide among Danes with multiple sclerosis. | Brønnum-Hansen et al.,17 2005 | Denmark | The study was based on the link between the Danish Multiple Sclerosis Registry and the Causes of Death Registry (10,174 individuals diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in the period from 1953 to 1996) | The risk of suicide was more than twice that of the general population |

With respect to the risk factors associated with suicide, studies have shown that depression is strongly associated; depression is found in 25% and would be related to MS-related pain, fatigue, anxiety and distress from the diagnosis and the disability.16,18 Various psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder, psychotic syndrome, drug abuse and bulimia nerviosa are related as well.18 Other risk factors would be being single, a widow/widower or divorced, and having fewer years of education.18 The association with the degree of disability and the time the disease has lasted does not seem clear.16 The majority of the suicides occurred during the first 5 years after the diagnosis; the younger patients, especially males, had were at greater risk.17

Much has been written about interferon beta (IFNβ) and its possible link to depression. A few studies report cases in which IFNβ use was associated with the appearance of altered mood states.19 However, a systematic review on the subject published in 2017 concluded that there was no clear relationship between IFNβ and depression, according to the majority of the studies.20 A history of depression would count as a factor of risk for developing depression again during the first 6 months of treatment; however, this history is not enough to contraindicate IFNβ.20

Alzheimer's disease (AD)Based on the articles reviewed, there is no clear association between suicide and dementia. In fact, there seems to be a rate similar to that of the general population21,22 (Table 3).

Summary of articles on Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

| Title | Author/year | Country | Population/design | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex Relationship Between Suicide, Dementia and Amyloid | Conejero et al.,21 2018 | France | Literature review of articles that focused on suicidal behaviour and dementia (2000−2017), 31 articles | The risk of suicide increases during the early stage of cognitive impairment. However, such retrospective analyses do not allow emphasising any causal relationship between dementia and suicidal behaviour |

| Considerations for the assessment of suicidal ideation and behavior in older adults with cognitive decline and dementia | Alphs et al.,23 2016 | USA | Literature review of suicidal behaviour in the elderly with dementia | The results are fairly contradictory |

| Predictors of suicide in patients with dementia | Seyfried et al.,22 2011 | USA | Retrospective study. | 241 patients with AD died by suicide. Patients with AD and neuropsychiatric symptoms are at greater risk of suicide. |

| Patients aged 60 years or older with dementia from 2001 to 2005. The final sample included 294,952 patients | 75% of the deaths occurred after a recent diagnosis of dementia. | |||

| Anxiety and early age increased the risk of suicide |

Various early behaviour disorders (such as depression) and problems with decision-taking are related to cerebral lesions at the frontal level, which could contribute to increasing the risk of suicide.21

Suicidal thoughts in older adults can trigger or precipitate cognitive impairment, as the response to stress is increased by the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.21 However, some findings suggest that the suicidal behaviour in these patients might be a consequence and complication of neurocognitive impairment.21

The studies conclude that, if there is suicidal ideation, it occurs in early stages of the disease and in the 6 months after diagnosis. These thoughts arise from a greater consciousness of cognitive impairment, along with a certain feeling of being a burden for other people and of stress from the loss of autonomy, with greater prevalence of depression. In the early stages, being male and having a high level of education constitute risk factors.21 As the dementia advances, the risk tends to diminish due to the individual’s inability to prepare and carry out a plan; in these later stages, caregivers supervise the individuals more closely, as well.21

We did not find much knowledge about any additional risk represented by specific drugs normally used in dementia.23

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)We have seen greater relative risk of suicide among the patients with ALS than among the general population in countries such as Denmark and Sweden; however, compared with other groups of patients with cancer, this tendency did not continue over time24 (Table 4).

Summary of studies on amyloid lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Huntington’s disease (HD).

| Title | Author/year | Country | Population/design | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide among patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | Fang et al.,24 2008 | Sweden | Population cohort in Sweden between 1965 and 2004 with 6642 patients, compared with the suicide rates of the general Swedish population | Risk of suicide almost 6 times higher among patients with ALS compared with the general population. The highest relative risk of suicide was seen during the first year after the diagnosis |

| Suicidal ideation in a European population with Huntington's disease | Hubers et al.,28 2013 | Europe | Study of 2106 carriers of HD mutations | 8.0% backed suicidal ideation. Risk factors are being depressed and benzodiazepine use |

| Critical periods of suicide risk in Huntington's disease | Paulsen et al,27 2005 | EE. UU. | Suicidal ideation was examined in 4171 individuals in the Huntington Study Group database | Two critical periods for a greater risk of suicide: immediately before receiving the diagnosis and when independence decreases |

Being male, being in one’s 60s, and realising the seriousness of the disease, the ineffectiveness of treatment and the progressive dependence on caregivers mean that patients with this disease think about ending their lives.24 Depressive states, desperation and the desire for a quick death are risk factors lead to suicidal behaviour.25

The highest relative risk was during the first year after diagnosis. This peak responds to the strong emotional burden that such a diagnosis entails, while the lack of autonomy in more advanced stages prevents carrying out suicide attempts.24

Huntington’s disease (HD)Suicide is a serious problem among patients with HD, considering its high frequency.26 The period just before the formal diagnosis of the disease is the time of greatest risk, as well as the period just after, in the early stages of HD, when the patients begin to become aware of their evident loss of independence27 (Table 4).

Anxiety, depressed mood, aggressiveness, previous suicide attempts and benzodiazepine use are risk factors for suicidal behaviour.28

ConclusionBased on the data obtained, we conclude that there is no clear evidence that relates suicidal behaviour and neurodegenerative diseases in the case of PD and AD. There is more agreement about such a relationship in MS, ALS and HD. Research has revealed a series of risk factors that are associated with suicidal behaviour; knowing these factors would help to prevent suicide. The nurse’s consultation, because it features continuity with and follow-up of these patients from the initial disease stages, is the ideal scenario for a systematic approach to these questions. Protocols and detection and action strategies on suicidal behaviour need to be created and should be focused on both the patients and their social and family settings. For successful implementation of such protocols and strategies, a training plan on these subjects would be necessary.

FundingThe authors declare that there was no public or private funding for this study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez Calero MG, Jiménez Galiano AB. Enfermedad neurodegenerativa y suicidio. Rev Cient Soc Esp Enferm Neurol. 2022;55:25–32.