Pharmacoinvasive therapy (PIT) is feasible in patients with acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation (STEMI) when timely primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is unavailable. In this study, we compared women who underwent successful reperfusion PIT with those who required rescue PCI, to identify potential predictors of thrombolytic failure.

MethodsFrom January 2010 to November 2014, 327 consecutive women with STEMI were referred to a tertiary hospital, 206 after successful thrombolysis (63%) and 121 who required rescue PCI. The groups were compared regarding demographic, clinical and angiographic outcomes, and clinical (TIMI, GRACE, and ZWOLLE CADILLAC) and bleeding (CRUSADE) risk scores. A multivariate logistic regression model was used to identify predictors of thrombolytic failure.

ResultsThere was no significant difference between the demographic characteristics or the medical history of the groups. Rescue PCI group had significantly higher values of the evaluated scores. Clinical hospital complications and mortality (2.5% vs. 22.0%; p < 0.0001) were more frequent in rescue PCI group. The independent variables associated with rescue PCI were pain-to-needle time > 3h (OR: 3.07, 95%CI: 1.64 to 5.75; p < 0.0001), ZWOLLE score (OR: 1.25; 95%CI: 1.14 to 1.37; p = 0.0001) and creatinine clearance (OR: 1.009, 95%CI: 1.0 to 1.02; p = 0.04).

ConclusionsWomen with STEMI who underwent PIT and who required rescue PCI had significantly higher mortality compared to those who achieved initial success of PIT with elective PCI. Pain-to-needle time > 3h, ZWOLLE score and creatinine clearance were independent predictors of the need for rescue PCI.

A estratégia fármaco-invasiva (EFI) é viável em pacientes com infarto agudo do miocárdio com supradesnivelamento do segmento ST (IAMCST), quando a intervenção coronária percutânea (ICP) primária em tempo hábil não é possível. Neste estudo, comparamos mulheres submetidas à EFI com sucesso para reperfusão àquelas que necessitaram de ICP de resgate, para identificar possíveis preditores de insucesso do trombolítico.

MétodosDe janeiro de 2010 a novembro de 2014, 327 mulheres com IAMCST e EFI foram encaminhadas ao hospital terciário, sendo 206 após trombólise com sucesso (63%) e 121 que necessitaram de ICP de resgate. Os grupos foram comparados quanto a variáveis demográficas, desfechos clínicos e angiográficos, e escores de risco clínico (TIMI, GRACE, ZWOLLE e CADILLAC) e de sangramento (CRUSADE). Um modelo de regressão logística multivariada foi utilizado para identificar preditores de insucesso do trombolítico.

ResultadosNão houve diferença significativa entre as características demográficas ou os antecedentes clínicos dos grupos. O grupo ICP de resgate apresentou valores significantemente maiores dos escores avaliados. Complicações clínicas hospitalares e mortalidade (2,5% vs. 22,0%; p < 0,0001) foram mais frequentes no grupo ICP de resgate. As variáveis independentes associadas à ICP de resgate foram tempo dor-agulha > 3 horas (OR 3,07; IC95% 1,64-5,75; p < 0,0001), escore ZWOLLE (OR 1,25; IC95% 1,14-1,37; p =0,0001) e clearance de creatinina (OR 1,009; IC95% 1,0-1,02; p = 0,04).

ConclusõesMulheres com IAMCST submetidas à EFI e que necessitaram de ICP de resgate tiveram mortalidade significativamente maior quando comparadas àquelas que obtiveram sucesso inicial da EFI com ICP eletiva. Tempo dor-agulha > 3 horas, escore de ZWOLLE e clearance de creatinina foram preditores independentes da necessidade de ICP de resgate.

Although primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the gold standard for patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (STEMI), low availability still prevents its broad use, as recommended by the most contemporary guidelines.1,2 Therefore, pharmacoinvasive therapy (PIT) has shown to be a feasible and valuable option in terms of public health, with efficacy results similar to those of primary PCI in several studies, and in national and international registries.3–5 In brief, PIT is the rapid application of a fibrin-specific thrombolytic therapy in primary care, followed by transfer to cardiac catheterization in 3-24h and performance of PCI in the culprit artery, if applicable. However, its weak point is thrombolytic therapy failure in one-third of cases. In the STREAM randomized trial,4 which compared PIT with primary PCI in almost 1,900 patients, rescue PCI occurred in 36% of cases.

STEMI is the leading cause of death among Western women and is already a leading cause of death among women in Brazil.6,7 The authors recently analyzed mortality data and major cardiac events in women with STEMI submitted to PIT and observed mortality rates twice as high as those observed in men.8 However, in the multivariate analysis, gender was not a risk factor in itself, but rather the fact that women presented more risk factors.

The present analysis compared women with STEMI submitted to PIT who achieved successful lytic reperfusion with women who required rescue PCI, identifying possible predictors of thrombolytic therapy failure.

MethodsFrom January 2010 to November 2014, 1,261 patients were prospectively included in the Sao Paulo ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) Registry, as specified in a previously published protocol3 and also in clinicaltrials.org NCT02090712. In this registry, patients with STEMI were treated with up to 12h of evolution using preferably primary PCI, but performing PIT if PCI was not available. Of these, 327 women (26% of the cohort) were treated with PIT and early elective catheterization (PIT, n = 206) or rescue PCI after failed thrombolysis (rescue PCI, n = 121). PIT success was defined as systematic cardiac catheterization and elective PCI, if necessary, performed 3 to 24hours after thrombolytic use. The criteria to define reperfusion failure were persistent chest pain in prethrombolysis levels, and persistent ST-segment elevation > 50% of the original elevation or early relapse or symptom worsening, with or without hemodynamic instability. These two groups were compared for demographic variables, clinical outcomes (mortality at catheterization and in-hospital mortality), pain-to-needle and doorto-needle time, risk scores (TIMI, GRACE, ZWOLLE, CADILLAC),9,10 risk of bleeding (CRUSADE),11 and complications such as congestive heart failure (CHF), cardiogenic shock, total atrioventricular block (TAVB), major and minor bleeding, and stroke. Left ventricular ejection fraction was obtained in the echocardiographic assessment performed within the first 48hours.

DefinitionsThrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow and myocardial blush were assessed as previously reported 12,13 Creatinine clearance was estimated according to the Cockcroft-Gault formula.14 Renal failure was defined as the presence of creatinine clearance estimated at < 60mL/min. Bleeding severity was established according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria15 Patients considered as having major bleeding were those with BARC ≥ 3; minor bleeding, those with BARC < 3. Death during catheterization was defined as death that occurred in the hemodynamics laboratory, during the index procedure.

Statistical analysisData were prospectively stored in an ExcelTM spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, USA) and submitted to statistical analysis using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS), version 22.0. Continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations, and categorical variables as absolute numbers and percentages. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson's chi-squared test, while numerical variables with normal distribution were compared using Student's t-test or the Mann-Whitney test, when applicable. Moreover, stepwise logistic regression was performed to evaluate independent predictors of rescue PCI. Statistically significant variables in the univariate analysis were included in the regression, in addition to those considered important as rescue PCI predictors, such as pain-to-needle and door-to-needle time. Interactions between the several risk scores, age, and renal failure were corrected. P-values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

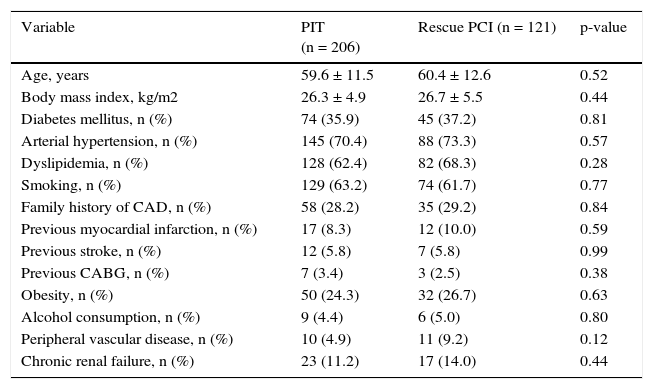

ResultsThe rate of need for rescue PCI in this analysis was 37.0%. Age in the overall group ranged from 24 to 86 years, with a mean of 59.9 ± years. There were no significant differences in any demographic variable or clinical history between the two groups (Table 1).

Demographic and clinical data.

| Variable | PIT (n = 206) | Rescue PCI (n = 121) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 59.6 ± 11.5 | 60.4 ± 12.6 | 0.52 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.3 ± 4.9 | 26.7 ± 5.5 | 0.44 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 74 (35.9) | 45 (37.2) | 0.81 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 145 (70.4) | 88 (73.3) | 0.57 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 128 (62.4) | 82 (68.3) | 0.28 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 129 (63.2) | 74 (61.7) | 0.77 |

| Family history of CAD, n (%) | 58 (28.2) | 35 (29.2) | 0.84 |

| Previous myocardial infarction, n (%) | 17 (8.3) | 12 (10.0) | 0.59 |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 12 (5.8) | 7 (5.8) | 0.99 |

| Previous CABG, n (%) | 7 (3.4) | 3 (2.5) | 0.38 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 50 (24.3) | 32 (26.7) | 0.63 |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | 9 (4.4) | 6 (5.0) | 0.80 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 10 (4.9) | 11 (9.2) | 0.12 |

| Chronic renal failure, n (%) | 23 (11.2) | 17 (14.0) | 0.44 |

PIT: pharmacoinvasive therapy; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; CAD: coronary artery disease; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft.

On admission, mean blood pressure and heart rate (76.5 ± 15 bpm vs. 78 ± 21 bpm; p = 0.36) were similar; however, patients from the rescue PCI group showed lower systolic blood pressure (132.8 ± 24.6mmHg vs. 126 ± 31mmHg, p = 0.03). Mean door-to-needle time (1.9 ± 2.0hours vs. 2.0 ± 3.0hours; p = 0.82) and pain-to-needle time (8.3 ± 13.6hours vs. 7.9 ± 16.7hours, p = 0.85) were also the same in both groups. Mean time between the onset of thrombolysis and coronary angiography was 18.6 ± 17.0hours in PIT group vs. 7.3 ± 6.5hours in the rescue PCI group (p < 0.001).

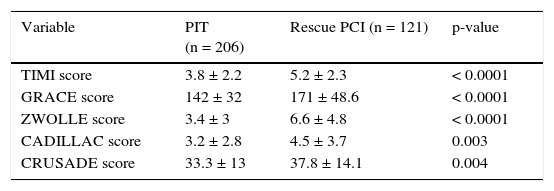

Regarding the mortality risk scores (TIMI, GRACE, ZWOLLE and CADILLAC) or bleeding score (CRUSADE), significantly higher values were observed in the rescue PCI group (Table 2).

Comparison of mean values of risk scores between groups.

| Variable | PIT (n = 206) | Rescue PCI (n = 121) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIMI score | 3.8 ± 2.2 | 5.2 ± 2.3 | < 0.0001 |

| GRACE score | 142 ± 32 | 171 ± 48.6 | < 0.0001 |

| ZWOLLE score | 3.4 ± 3 | 6.6 ± 4.8 | < 0.0001 |

| CADILLAC score | 3.2 ± 2.8 | 4.5 ± 3.7 | 0.003 |

| CRUSADE score | 33.3 ± 13 | 37.8 ± 14.1 | 0.004 |

PIT: pharmacoinvasive therapy; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

The mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 53.0 ± 11.5% in the PIT group vs. 47.4 ± 10.7% in the rescue PCI group (p < 0.0001). As for the distribution of culprit arteries, no significant difference was found in the incidence of lesions occurring in the territory of the left anterior descending artery (31% vs. 42.5%), left circumflex artery (11% vs. 6.5%), or right coronary artery (52% vs. 39%) between the PIT and rescue PCI groups, respectively (p = 0.35).

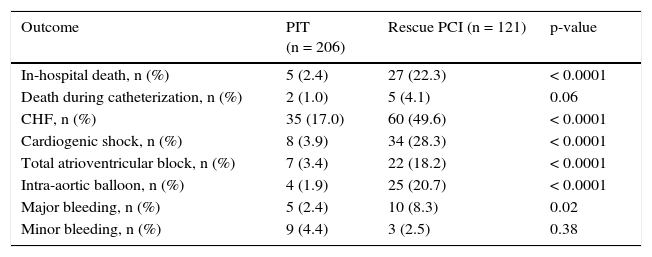

During the in-hospital evolution, severe complications of AMI were significantly more frequent in patients from the rescue PCI group (Table 3). Only one patient in each group had a hemorrhagic stroke.

In-hospital clinical evolution.

| Outcome | PIT (n = 206) | Rescue PCI (n = 121) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital death, n (%) | 5 (2.4) | 27 (22.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Death during catheterization, n (%) | 2 (1.0) | 5 (4.1) | 0.06 |

| CHF, n (%) | 35 (17.0) | 60 (49.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Cardiogenic shock, n (%) | 8 (3.9) | 34 (28.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Total atrioventricular block, n (%) | 7 (3.4) | 22 (18.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Intra-aortic balloon, n (%) | 4 (1.9) | 25 (20.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Major bleeding, n (%) | 5 (2.4) | 10 (8.3) | 0.02 |

| Minor bleeding, n (%) | 9 (4.4) | 3 (2.5) | 0.38 |

PIT: pharmacoinvasive therapy; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; CHF: congestive heart failure.

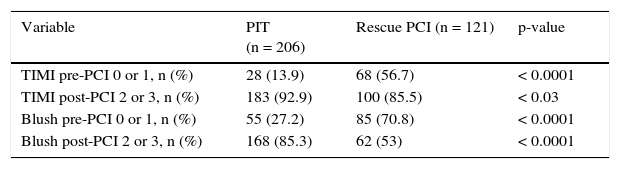

Table 4 shows the initial and final flow angiographic variables, demonstrating a significant reduction in procedural success in the rescue PCI group (reduction in TIMI 2 or 3 frequency at the end of the procedure and of myocardial blush flow 2 or 3).

Comparison of TIMI flow and myocardial blush preand post-percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

| Variable | PIT (n = 206) | Rescue PCI (n = 121) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIMI pre-PCI 0 or 1, n (%) | 28 (13.9) | 68 (56.7) | < 0.0001 |

| TIMI post-PCI 2 or 3, n (%) | 183 (92.9) | 100 (85.5) | < 0.03 |

| Blush pre-PCI 0 or 1, n (%) | 55 (27.2) | 85 (70.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Blush post-PCI 2 or 3, n (%) | 168 (85.3) | 62 (53) | < 0.0001 |

PIT: pharmacoinvasive therapy.

In-hospital mortality (all-cause) occurred in 2.5% of the PIT group and in 22% of the rescue PCI group (p < 0.0001), with a trend for higher mortality related to catheterization.

Independent variables associated with the need for rescue PCI were pain-to-needle time > 3hours, with an odds ratio of 3.07 (95%CI: 1.645–5.751; p < 0.0001), ZWOLLE score, with an odds ratio of 1.25 (95%CI: 1.139–1.370; p = 0.0001), and creatinine clearance, with an odds ratio of 1.009 (95%CI: 1.0–1.019; p = 0.04).

DiscussionThis study, which included 327 women submitted to PIT, showed that the population in need of rescue PCI had a higher number of adverse events and significantly higher number of deaths than the population submitted to clinically successful PIT. Although these data are known in overall post-thrombolysis treatment, this is one of the first reports in a population submitted to PIT, confirming that the results can be superimposed to those of the population treated without PIT.

The low representation of women in several studies on coronary artery disease hinders the use of conclusions obtained from these studies in the treatment of this important segment of the population. Therefore, the analysis of large registries, such as the present, which included all patients receiving treatment after clinical indication (all-comers), helps make better use of resources and treatments, as well as understanding possible treatment failure mechanisms.

Although widely known as a population at high risk of death during STEMI, when adjusted for age and comorbidities, the importance of the female gender as a risk factor for mortality is still debatable.16 The risk reduction provided by thrombolysis in women with STEMI is also lower than in men,17,18 which may be due to older age at presentation, delay in seeking medical care and the emergency room, and more difficult diagnosis when compared to men.19

The present study's rate for rescue PCI was 37%. In the STREAM trial, the most important comparison study between PIT and primary PCI, 1,892 patients were randomized with up to 3hours after myocardial infarction onset. For the combined endpoint of death/shock/ CHF or reinfarction at 30 days, the groups had similar results. In that study, although with much shorter time until treatment than the present study, the rate for rescue PCI was 36.3%. In the NCDRTM registry, 41.5% of patients receiving fibrinolysis required rescue PCI.20

With transfer times that remain long between the primary hospital and the tertiary center, which are characteristic of the authors’ experience, the present study's rescue PCI rate might include possible cases of early reocclusion. However, of more concern is the possibility that this similarity in the need for rescue PCI among this population and that in literature represents a diagnostic underestimation that must be explored.

In general, as shown above, the present study's rate of bleeding/ vascular complications is low and comparable to that in literature (4.6%),21 especially when considering the procedures performed via femoral artery only. Similar to other experiences, the present population had a moderate risk of bleeding based on the CRUSADE score and the frequency of bleeding was correctly predicted.22 However, this score has not been adequately tested for this scenario (PIT and rescue PCI). The higher frequency of major bleeding in the rescue PCI group (2.4% vs. 8.3%) may be secondary to multiple mechanisms, such as earlier catheterization, longer and more complex procedures, or more frequent use of antithrombotic drugs (data not reported here). The similar frequency of major bleeding when comparing primary PCI and PIT has already been established,4 but the increased risk associated with the need for rescue PCI has been reported in another large registry, reaching 13%.20

In a previous publication from the authors’ experience, with a population of 469 patients, including 140 women, female patients showed higher mortality than males (9.3% vs. 4.9%; p = 0.07), but gender was not a predictor of death or major adverse events in the multivariate analysis, with the difference in the incidence of death due to more frequent comorbidities in women.8 In the present study, it was observed that the group undergoing thrombolysis without success and submitted to rescue PCI had a demographic and clinical profile similar to that of women with clinically successful reperfusion. Both groups were characterized by the high frequency of known risk markers, such as diabetes, renal failure, and previous coronary heart disease (infarction or myocardial revascularization). The present population also had a higher risk profile than that in literature.4,23 In the authors’ overall experience, including both genders, total mortality for PIT is approximately 6%,8,24 and was 9.7% in the group of women included here. Mortality rates below 5% were observed in the STREAM and in the CAPTIM studies, which randomized patients with up to 3hours and 6hours of evolution, respectively.4,23 Particularly in the PIT group, consisting only of women with successful thrombolysis and early PCI, a mortality rate of 2.5% was observed, which reinforces this approach for a large portion of these patients. Associated with the finding of ischemia time longer than 3hours as an independent predictor of reperfusion failure (OR: 3.07, 95%CI: 1.645 5.751; p < 0.0001), it also demonstrates the need for policies directed at the early use of thrombolytic agents, preferably in the emergency units, outpatient clinics, or pre-hospital admission emergency rooms or ambulances, because by increasing the rates of successful lytic reperfusion and preserving viable myocardium, surely there will be a decrease in mortality.

In addition to time of ischemia and presence of renal dysfunction, the latter a known predictor of mortality and complications in cardiovascular disease, the ZWOLLE score was a predictor of rescue PCI. The finding of higher risk scores in women compared to men is well known8,25 The ZWOLLE score, a validated scoring system for identifying low-risk patients after primary PCI who would be eligible for early discharge,9 was a predictor of unsuccessful thrombolysis in the group of female individuals. As one of the score components includes time of ischemia, perhaps this was the main score component that influenced its importance in this population. It is considered that patients with scores ≤ 3 would be subject to early discharge after primary PCI; even considering a high-risk population, as shown here, the PIT group score was very close to this value, suggesting that this index also deserves validation in the group of post-thrombolysis patients.

Unlike the international experience of randomized studies,1,2 this registry still observed that the pain-to-needle and door-to-needle times were high and represented a significant limitation for further improvement of results. However, they were also the expression of the public health care reality in a large urban city in Brazil.

Indicators of reperfusion after thrombolytic therapy are not lower in female than in male patients. In a large angiographic review of patients enrolled in four studies of the TIMI group, including 2,596 patients, the degree of myocardial perfusion (blush) and the corrected TIMI frame count were similar between the genders25 after thrombolysis and after PCI. The authors concluded that differences in reperfusion did not account for the difference in mortality. In the present study, 71% of patients with rescue PCI showed initial blush of 0 or 1 (consistent with a diagnosis of unsuccessful thrombolysis) and in 47%, this abnormal flow was maintained after PCI, although the rate of TIMI 2 or 3 and the absence of residual lesion (successful PCI) were present in 85.5%. In those receiving late treatment, such as the present patients, the rate of inadequate reperfusion was, therefore, higher and more evident.

LimitationsAs in any retrospective analysis, the data were subject to varying confounders, which can alter the results. The differences regarding patterns of medication use were not analyzed, which could certainly affect reperfusion results. No detailed data on the angiographic analysis, location, and complexity of the culprit lesion were supplied in this publication.

ConclusionsThis study demonstrated that female patients submitted to rescue percutaneous coronary intervention showed high frequency of heart failure and cardiogenic shock, and that bleeding rates were higher than those observed in the overall population. The degree of myocardial perfusion (blush) was significantly reduced in patients after rescue percutaneous coronary intervention. As previously demonstrated by this group, the occurrence of inadequate reperfusion is an important predictor of death and, here, it may have been determinant of mortality rates in the percutaneous coronary intervention rescue group, which was almost ten-fold higher than the mortality rate observed in the successful pharmacoinvasive therapy group. It is speculated that this inadequate reperfusion may be related to long pain-to-needle time and pain-to-rescue PCI time.

Funding sourcesNone declared.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.