Human papillomavirus infection is the most common sexually-transmitted infection and its relationship with vaginal microbiota is not entirely clear. The aims of this study were: (1) to determine the prevalence of infection with high-risk (hr)-HPV types in different age groups; (2) to describe the hr-HPV types according to the grade of cervical squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL); (3) to establish the prevalence of bacterial vaginosis (BV), yeasts and trichomoniasis in the different age groups studied according to the type of hr-HPV detected. A total of 741 patients underwent clinical examination and collection of vaginal fornix to study basic vaginal states (BVS) and culture. hr-HPV types were determined using multiple isothermal real-time amplification. Patients were divided into three age groups: Group 1, 18–24 years (n=138), Group 2, 25–50 years (n=456) and Group 3, over 50 years (n=147). All groups were further divided into HPV-negative, HPV-positive patients without lesion, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (L-SIL), high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion/squamous cervical carcinoma (H-SIL/SCC). HPV16 type was the most prevalent in H-SIL/SSC 50% (22/44) followed by hr-HPV non-16/18 13.6% (6/44) and in L-SIL 27% (17/63) followed by HPV31–33 14.3% (9/63). In Group 1, HPV16 was detected in 63.3% (7/11) of H-SIL/SCC lesions; in Group 2, HPV16 was detected in 45.5% of H-SIL/SCC lesions (14/32); and in Group 3, HPV16 was detected in one case of H-SIL/SCC. The most prevalent condition was BV in the three groups. In Group 1, 54.2% of HPV16 patients had associated BV. A high prevalence of hr-HPV infection was detected in the 18–24-year age group. HPV16 was the most prevalent type in both the 18–24 and 25–50-year age groups and both HSIL/SSC and L-SIL. BV was the condition most frequently detected, especially in the 18-24–year age group.

La infección por el virus del papiloma humano (VPH) es la infección de transmisión sexual más frecuente y su relación con la microbiota vaginal no es clara. Los objetivos de este estudio fueron: 1) determinar la prevalencia de infección por tipos de VPH de alto riesgo (VPH-ar) en diferentes grupos etarios; 2) describir los tipos de VPH-ar según el grado de lesión escamosa intraepitelial cervical (SIL); 3) establecer la prevalencia de vaginosis bacteriana (VB), levaduras y tricomonosis en los diferentes grupos etarios según el tipo de VPH-ar detectado. Se realizó un examen clínico y se tomó muestra del fondo de saco vaginal a 741 pacientes para el estudio de estados vaginales básicos (EVB) y cultivo. Los tipos de VPH-ar se determinaron por amplificación isotérmica múltiple en tiempo real. Las pacientes se dividieron en tres grupos etarios: grupo 1 (G1), 18-24 años (n=138); grupo 2 (G2), 25-50 años (n=456) y grupo 3 (G3) ≥ 50 años (n=147). Los hallazgos se clasificaron como VPH-negativos, VPH-positivos sin lesión, con SIL de bajo grado (L-SIL), con SIL de alto grado (H-SIL)/carcinoma de cuello uterino (CCU). El VPH16 fue el más frecuente en las mujeres con H-SIL/SSC (50%; 22/44), seguido del VPH-ar no 16/18 (13,6%; 6/44). VPH16 también fue el más común en aquellas con L-SIL (27%; 17/63), seguido del VPH31-33 (14,3%; 9/63). En el G1, el VPH16 se asoció con el 63,3% (7/11) de los casos de H-SIL/CCU. En el G2, el VPH16 se asoció con un 45,5% de casos de H-SIL/CCU (14/32). El único caso de H-SIL/CCU en el G3 estuvo asociado al VPH16. La condición más prevalente fue la VB en los tres grupos. En el G1, el 54,2% de las pacientes con HPV16 tenían VB asociada. Se detectó alta prevalencia de infección por VPH-ar en el G1. El VPH16 fue el más prevalente en los grupos de 18-24 años y de 25-50 años, así como en pacientes con H-SIL/CCU y con L-SIL. La VB fue la entidad detectada con mayor frecuencia, especialmente en el grupo de 18-24 años.

Worldwide, cervical cancer is the fourth most common carcinoma in women, with an estimated incidence of 662301 new cases per year in 2022, according to the World Health Organization (WHO)17. It represents a significant public health issue in Latin America and the Caribbean. In Argentina, the incidence is approximately 4800 cases annually56, and the mortality rate from cervical cancer in the country is 9.4 deaths per 100000 women. The provinces of Misiones and Formosa are in the highest quintile of cervical cancer mortality (age-adjusted rate [AAR]: between 14.7 and 17.3). Conversely, the lowest quintile includes the jurisdictions of La Rioja, Mendoza, the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, Córdoba, Entre Ríos, and Santa Cruz (AAR: 4.4–7.0 deaths per 100000 women)16.

Currently, the WHO identifies human papillomavirus (HPV) as the causal agent of cervical cancer. The family Papillomaviridae includes a wide variety of HPV genotypes with varying oncogenic potential, classified into high- and low-risk types. The most common low-risk HPV types are HPV6 and HPV11, often detected in benign genital warts18. Among the most prevalent high-risk types, HPV16, HPV18, HPV31, and HPV45 are frequently found in cervical squamous cell carcinomas, accounting for nearly 80% of cases14. HPV16 and HPV18 are responsible for 54.4% and 15.9% of all cases worldwide, respectively64. The identification of high-risk human papillomavirus (hr-HPV) types as a necessary cause of anogenital cancer was a significant milestone in understanding the pathology and its preinvasive stages. With an estimated 291 million HPV-positive women worldwide in 200713, HPV infection has remained one of the most common viral infections in the world. Moreover, based on available data, about 98% of women are exposed to HPV infection, and about 30%47 to 40%62 are susceptible to infection. In fact, 50% of women under 30 may test positive for HPV, which corresponds to a transient infection that can resolve within three years50, as the active squamous metaplasia occurring in young women appears to increase risk for transitory HPV infection in this group32. On the other hand, in postmenopausal women, a deterioration in the immune response (decreased capacity for antigen presentation) of the host would affect the clearance of HPV20.

Upon HPV acquisition, most individuals are able to mount a strong cell-mediated immune response within 1–2 years, resulting in loss of HPV detectability – a phenomenon often defined as viral clearance. However, a growing body of literature reports that even when HPV is undetectable by conventional tests, it remains in the basal layers of the epithelium of the uterine cervix as a latent or low-level chronic infection, with subsequent risk of redetection of HPV during periods of relative immune suppression40.

In cases of viral latency, reactivation can lead to persistent infection and, ultimately, to the development of H-SIL21,25,36. Rarely (3.3% of H-SIL cases), H-SIL can progress to SCC36. Persistence of hr-HPV infection, abnormal cytology and, immunosuppression have been reported as key factors in the development of SCC.

In addition to the HPV types, smoking33, immunocompromised status15,30 and various viral types4,72 and bacterial infections61 have been associated with the persistence and progression of HPV infection. Furthermore, a significant correlation has been found between the vaginal microbiota and the natural history of HPV infection37.

The vagina and its bacterial communities constitute a delicately balanced ecosystem. These bacterial communities play a protective role against lower genital tract conditions such as bacterial vaginosis (BV), yeasts, sexually-transmitted infections (STIs) and urinary tract infections (UTIs). Lactobacilli are the most abundant species in vaginal communities in women of reproductive age, benefiting the host as they can produce lactic acid that reduces vaginal pH and protects against potentially harmful microorganisms41. In healthy adult women, the vaginal pH is between 3.5 and 4.5; and, in turn, the predominant species of lactobacilli keep the pH low through their glycogen fermentation activity, which protects the area against invasion by undesirable microorganisms9. Regarding the relationship between gynecological cancer and microbiome imbalance, the clearest example found so far is the development of HPV-related tumors. Furthermore, the presence of HPV may influence the vaginal microbial ecosystem, and the microbiome may play a significant role in susceptibility, persistence, and progression of HPV infection. For example, women with HPV infection have been shown to have increased levels of Lactobacillus gasseri and Gardnerella vaginalis, while a balanced microbiome with higher amounts of Lactobacillus crispatus is associated with a lower risk of HPV progression and greater viral clearance22,54.

This suggests that additional factors act along with the HPV virus to influence the risk of cervical cancer development.

The aims of this study were the following: (1) to determine the prevalence of infection with high-risk HPV (hr-HPV) types in different age groups; (2) to describe the hr-HPV types according to the grade of cervical squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL); and (3) to establish the prevalence of BV, yeasts and trichomoniasis in the different age groups studied according to the type of hr-HPV.

Materials and methodsThis was a consecutive, descriptive, cross-sectional study. We included 741 patients aged between 18 and 85 years with a history of sexual activity, regardless of the presence of symptoms of vaginal infection. They were recruited between October 2018 and June 2024. This study was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee and all patients gave their informed consent.

Inclusion criteria were: women over 18 years of age, without primary or secondary immunodeficiencies. The patient vaccination status in Group 1 was not included in the analysis because the vaccination schedule was completed in only 45% of the cases. Exclusion criteria were: patients who had received antibiotics (ATB) within 15 days prior to examination, pregnancy, genital malformations, patients undergoing treatment with corticosteroids or chemotherapy, no history of sexual activity and sexual intercourse within 48h prior to the study. The study population was classified into the following groups: Group 1 (18–24 years), Group 2 (25–50 years), Group 3 (older than 50 years). In turn, each age group was subdivided into HPV negative patients (Control Group), HPV-positive without lesions, L-SIL and H-SIL/SSC.

After signing the informed consent form, data were collected to complete the gynecological record. In addition, medical and epidemiological data of interest were collected. Samples were taken for cervical, exocervical and endocervical cytology.

After application of acetic acid, colposcopy was performed at 16× magnification. The data collected were catalogued according to the International Federation of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology classification (2011 version)5.

Cervical cytology was stained using the Papanicolaou technique, and reported according to the Bethesda classification (2014 version)52. Histological specimens were reported according to the LAST (lower anogenital squamous terminology) Project guidelines12. The microbiological study was performed on the sample of vaginal fornices using conventional methods and the study of basic vaginal states (BVS) according to the balance of the vaginal content (BAVACO) methodology:

- 1.

Gram and prolonged May-Grunwald Giemsa (MGG) stained smears.

- 2.

Wet smear examination with 1ml of physiological solution (PS).

- 3.

Wet smear examination with 1ml of KOH 10%.

- 4.

Liquid culture medium (modified thioglycolate) for Trichomonas vaginalis, with incubation for 7 days at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO259.

- 5.

Columbia agar base culture with 5% human blood and on Man Rogosa agar with 48-h incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, preserving the sample in Stuart's medium.

Yeasts were detected by wet smear examination with PS and 10% KOH and by culture on Sabouraud agar and blood agar. The analysis of T. vaginalis was conducted by direct microscopic observation with PS, prolonged MGG staining and culture on modified thioglycolate58,59. The diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis was made using Nugent's criteria53. The study of BAVACO included the morphological analysis of the vaginal content according to the relationship between the numerical value (NV) and the vaginal inflammatory reaction (VIR), identifying 5 BVS: normal microbiota (I), normal microbiota plus inflammatory reaction (II), intermediate microbiota (III), BV (IV) and non-specific microbial vaginitis (V)43. Detection of hr-HPV, a multiple isothermal amplification in real time, AmpFire Genotype HPV was performed, using the Catalog Number: GHPVF1618-100, which can identify the 31,51,39,16,35,68,18,59,33,66,45 58,56,53,52 HPV genotypes and an internal control (human β-globin gene), following the manufacturer's recommendations66. The hr-HPV viral types were grouped according to their phylogenetic relationships and to the prevalence of infection reported in previous studies from the Latin-American region3,7,11.

Statistical analysisThe prevalence of different conditions was expressed as percentage with their correspondence confidence interval 95% (95% CI). To compare the prevalence of vaginal conditions and their association with hr-HPV in the different groups and subgroups according to the lesion presented, the Chi-square test (χ2), odds ratio and Fisher's test were used. A p value <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Epi Data® version 7.2.2.6 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services).

ResultsThe mean age in Group 1 was 21.6 years (95% CI: 21.7–21.9; n: 138), Group 2 was 35.2 (95% CI: 34.5–35.8; n: 456) and Group 3 was 62.17 years (95% CI: 60.7–63.6; n: 147). Samples with no amplification of the internal control gene in the hr-HPV test were eliminated.

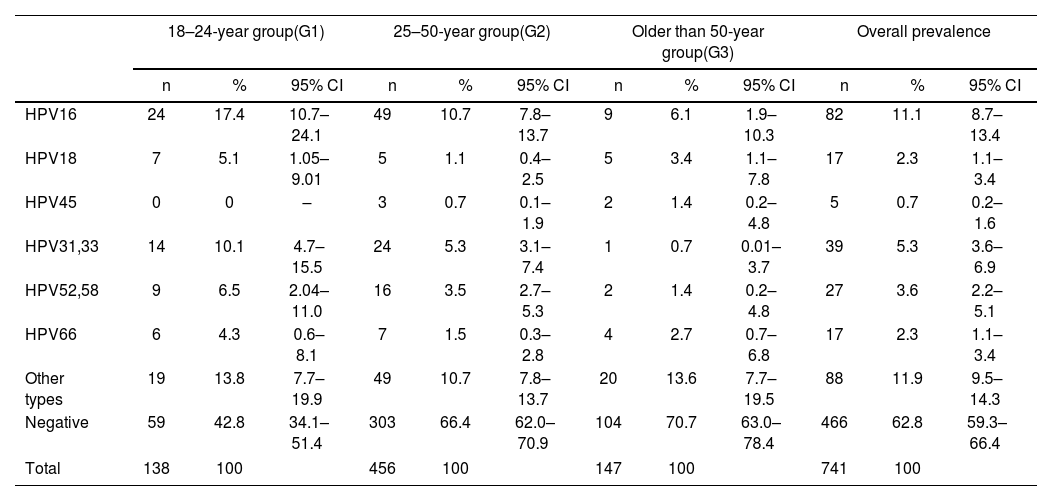

The prevalence of HPV infection is shown in Table 1. In the sample, the most prevalent hr-HPV group was hr-HPV non-16/18 11.9% (88/741) followed by HPV16 11.1% (82/741). In Group 1, the most prevalent hr-HPV type was HPV16 17.4% (24/138; 95% CI: 10.7–24.1) followed by hr-HPV non-16/18 13.8% (19/138; 95% CI: 7.7–19.9). In Group 2, the most prevalent HPV types were HPV16 10.7% (49/456; 95% CI: 7.7–19.9) and hr-HPV non-16/18 10.7% (49/456; 95% CI: 7.8–13.7). In Group 3, the most prevalent HPV types were hr-HPV non-16/18 13.6% (20/147; 95% CI: 7.8–13.7) followed by HPV16 6.1% (9/147; 95% CI: 1.9–10.3).

Prevalence of the different types of hr-HPV according to the age groups studied.

| 18–24-year group(G1) | 25–50-year group(G2) | Older than 50-year group(G3) | Overall prevalence | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | 95% CI | n | % | 95% CI | n | % | 95% CI | n | % | 95% CI | |

| HPV16 | 24 | 17.4 | 10.7–24.1 | 49 | 10.7 | 7.8–13.7 | 9 | 6.1 | 1.9–10.3 | 82 | 11.1 | 8.7–13.4 |

| HPV18 | 7 | 5.1 | 1.05–9.01 | 5 | 1.1 | 0.4–2.5 | 5 | 3.4 | 1.1–7.8 | 17 | 2.3 | 1.1–3.4 |

| HPV45 | 0 | 0 | – | 3 | 0.7 | 0.1–1.9 | 2 | 1.4 | 0.2–4.8 | 5 | 0.7 | 0.2–1.6 |

| HPV31,33 | 14 | 10.1 | 4.7–15.5 | 24 | 5.3 | 3.1–7.4 | 1 | 0.7 | 0.01–3.7 | 39 | 5.3 | 3.6–6.9 |

| HPV52,58 | 9 | 6.5 | 2.04–11.0 | 16 | 3.5 | 2.7–5.3 | 2 | 1.4 | 0.2–4.8 | 27 | 3.6 | 2.2–5.1 |

| HPV66 | 6 | 4.3 | 0.6–8.1 | 7 | 1.5 | 0.3–2.8 | 4 | 2.7 | 0.7–6.8 | 17 | 2.3 | 1.1–3.4 |

| Other types | 19 | 13.8 | 7.7–19.9 | 49 | 10.7 | 7.8–13.7 | 20 | 13.6 | 7.7–19.5 | 88 | 11.9 | 9.5–14.3 |

| Negative | 59 | 42.8 | 34.1–51.4 | 303 | 66.4 | 62.0–70.9 | 104 | 70.7 | 63.0–78.4 | 466 | 62.8 | 59.3–66.4 |

| Total | 138 | 100 | 456 | 100 | 147 | 100 | 741 | 100 | ||||

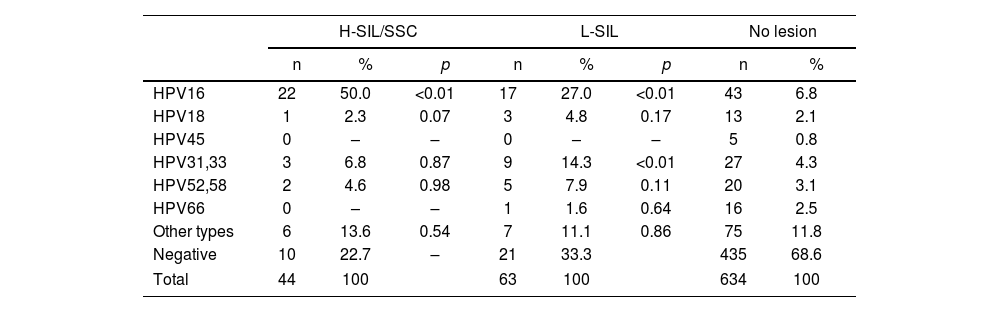

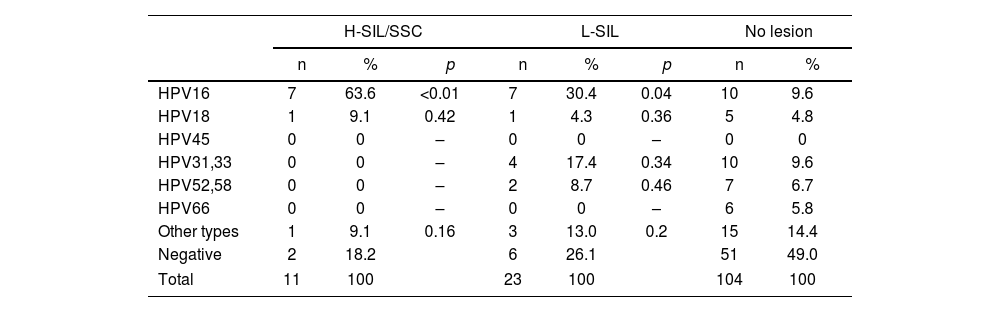

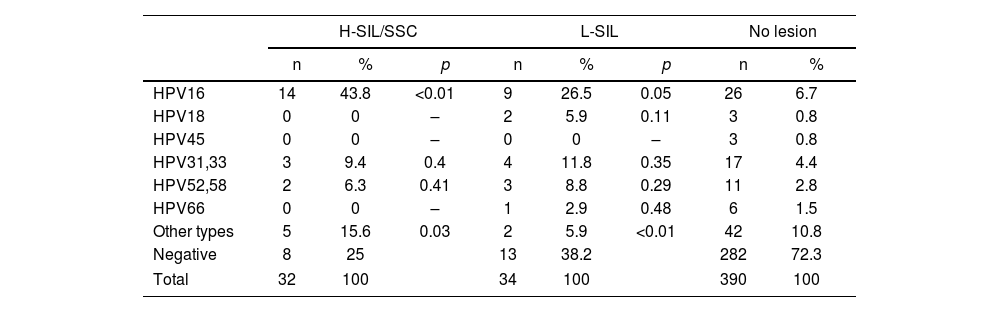

The prevalence of the different hr-HPV types according to lesions are shown in Tables 2–5. HPV16 type was the most prevalent in H-SIL/SSC 50% (22/44; p<0.01) followed by hr-HPV non-16/18 13.6% (6/44). HPV16 was the most prevalent in L-SIL 27% (17/63; p<0.01) followed by HPV31–33 14.3% (9/63; p<0.01). In Group 1, HPV16 was associated with 63.6% (7/11; OR 15.05; p<0.01) of H-SIL/SSC. In Group 2, HPV16 was associated with 43.8% of H-SIL/SSC (14/32; OR 4.41; p<0.01). In Group 3, one case of HPV16 associated with H-SIL/SSC was detected.

Prevalence of the different hr-HPV viral types according to the degree of SIL in the entire population.

| H-SIL/SSC | L-SIL | No lesion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | |

| HPV16 | 22 | 50.0 | <0.01 | 17 | 27.0 | <0.01 | 43 | 6.8 |

| HPV18 | 1 | 2.3 | 0.07 | 3 | 4.8 | 0.17 | 13 | 2.1 |

| HPV45 | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | – | 5 | 0.8 |

| HPV31,33 | 3 | 6.8 | 0.87 | 9 | 14.3 | <0.01 | 27 | 4.3 |

| HPV52,58 | 2 | 4.6 | 0.98 | 5 | 7.9 | 0.11 | 20 | 3.1 |

| HPV66 | 0 | – | – | 1 | 1.6 | 0.64 | 16 | 2.5 |

| Other types | 6 | 13.6 | 0.54 | 7 | 11.1 | 0.86 | 75 | 11.8 |

| Negative | 10 | 22.7 | – | 21 | 33.3 | 435 | 68.6 | |

| Total | 44 | 100 | 63 | 100 | 634 | 100 | ||

Prevalence of the different hr-HPV viral types according to the degree of SIL in the 18–24-year age group.

| H-SIL/SSC | L-SIL | No lesion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | |

| HPV16 | 7 | 63.6 | <0.01 | 7 | 30.4 | 0.04 | 10 | 9.6 |

| HPV18 | 1 | 9.1 | 0.42 | 1 | 4.3 | 0.36 | 5 | 4.8 |

| HPV45 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 |

| HPV31,33 | 0 | 0 | – | 4 | 17.4 | 0.34 | 10 | 9.6 |

| HPV52,58 | 0 | 0 | – | 2 | 8.7 | 0.46 | 7 | 6.7 |

| HPV66 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – | 6 | 5.8 |

| Other types | 1 | 9.1 | 0.16 | 3 | 13.0 | 0.2 | 15 | 14.4 |

| Negative | 2 | 18.2 | 6 | 26.1 | 51 | 49.0 | ||

| Total | 11 | 100 | 23 | 100 | 104 | 100 | ||

Prevalence of the different hr-HPV viral types according to the degree of SIL in the 25–50-year age group.

| H-SIL/SSC | L-SIL | No lesion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | |

| HPV16 | 14 | 43.8 | <0.01 | 9 | 26.5 | 0.05 | 26 | 6.7 |

| HPV18 | 0 | 0 | – | 2 | 5.9 | 0.11 | 3 | 0.8 |

| HPV45 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – | 3 | 0.8 |

| HPV31,33 | 3 | 9.4 | 0.4 | 4 | 11.8 | 0.35 | 17 | 4.4 |

| HPV52,58 | 2 | 6.3 | 0.41 | 3 | 8.8 | 0.29 | 11 | 2.8 |

| HPV66 | 0 | 0 | – | 1 | 2.9 | 0.48 | 6 | 1.5 |

| Other types | 5 | 15.6 | 0.03 | 2 | 5.9 | <0.01 | 42 | 10.8 |

| Negative | 8 | 25 | 13 | 38.2 | 282 | 72.3 | ||

| Total | 32 | 100 | 34 | 100 | 390 | 100 | ||

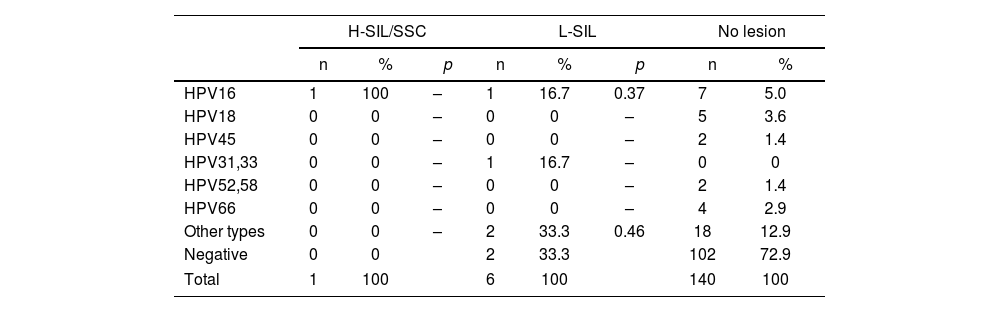

Prevalence of the different hr-HPV viral types according to the degree of SIL in the older than 50-year age group.

| H-SIL/SSC | L-SIL | No lesion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | |

| HPV16 | 1 | 100 | – | 1 | 16.7 | 0.37 | 7 | 5.0 |

| HPV18 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – | 5 | 3.6 |

| HPV45 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – | 2 | 1.4 |

| HPV31,33 | 0 | 0 | – | 1 | 16.7 | – | 0 | 0 |

| HPV52,58 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – | 2 | 1.4 |

| HPV66 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – | 4 | 2.9 |

| Other types | 0 | 0 | – | 2 | 33.3 | 0.46 | 18 | 12.9 |

| Negative | 0 | 0 | 2 | 33.3 | 102 | 72.9 | ||

| Total | 1 | 100 | 6 | 100 | 140 | 100 | ||

In all age groups (18–24 years, 25–50 years and above 50 years), BV exhibited a higher prevalence (34.0%, 31.1% and 15.3%) than yeasts (22.7%, 21.2% and 6.7%) and trichomoniasis (2.8%, 3.6% and 1.3%) respectively. These differences were statistically significant for the three groups (p<0.001).

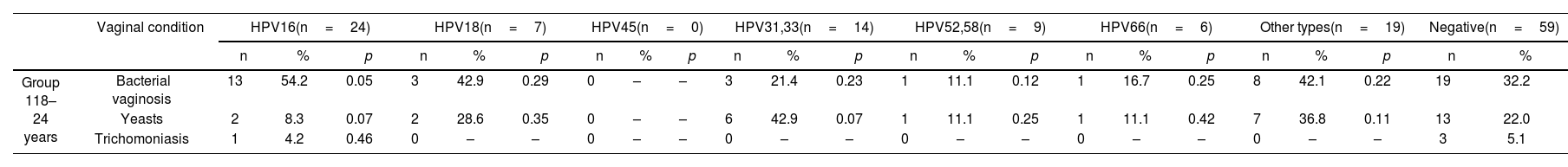

The prevalence of BV according to hr-HPV was as follows:

In Group 1, 54.2% (13/24) of patients with HPV16 were associated with BV (OR 2.49, p=0.05). In contrast, yeasts in this group were detected in 8.3% (2/24) of patients with HPV16 (OR 0.32, p=0.07) (Table 6). In Group 2, BV was associated with HPV16 in 34.7% (17/49; OR 1.18; p=0.3) of cases, and, with other types in 26.5% (13/49; OR 0.80; p=0.27). Yeasts were associated with HPV16 in 16.3% (8/49; OR 0.77; p=0.28), and with other types in 34.7% (17/49; OR 2.11, p=0.02). Trichomoniasis was associated with HPV45 (Table 6) in 66.7% (2/3; OR 48.5; p<0.01) of cases. In Group 3, BV was associated with HPV16 in 22.2% (2/9; OR 1.69; p=0.27) of cases and, yeasts with HPV66 (Table 6) in 25% (1/4; OR 4; p=0.17) of cases.

Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis, yeasts and trichomoniasis in all groups according to each type of hr-VPH.

| Vaginal condition | HPV16(n=24) | HPV18(n=7) | HPV45(n=0) | HPV31,33(n=14) | HPV52,58(n=9) | HPV66(n=6) | Other types(n=19) | Negative(n=59) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | ||

| Group 118–24 years | Bacterial vaginosis | 13 | 54.2 | 0.05 | 3 | 42.9 | 0.29 | 0 | – | – | 3 | 21.4 | 0.23 | 1 | 11.1 | 0.12 | 1 | 16.7 | 0.25 | 8 | 42.1 | 0.22 | 19 | 32.2 |

| Yeasts | 2 | 8.3 | 0.07 | 2 | 28.6 | 0.35 | 0 | – | – | 6 | 42.9 | 0.07 | 1 | 11.1 | 0.25 | 1 | 11.1 | 0.42 | 7 | 36.8 | 0.11 | 13 | 22.0 | |

| Trichomoniasis | 1 | 4.2 | 0.46 | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | – | 3 | 5.1 | |

| Vaginal condition | HPV16(n=49) | HPV18(n=5) | HPV45(n=3) | HPV31,33(n=24) | HPV52,58(n=16) | HPV66(n=7) | Other types(n=49) | Negative(n=303) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | ||

| Group 225–50 years | Bacterial vaginosis | 17 | 34.7 | 0.3 | 1 | 20 | 0.33 | 1 | 33.3 | 0.45 | 10 | 41.7 | 0.15 | 6 | 37.5 | 0.29 | 3 | 42.9 | 0.26 | 13 | 26.5 | 0.27 | 94 | 31.0 |

| Yeasts | 8 | 16.3 | 0.28 | 1 | 20 | 0.47 | 2 | 66.7 | 0.06 | 4 | 16.7 | 0.36 | 3 | 18.7 | 0.47 | 3 | 42.9 | 0.09 | 17 | 34.7 | 0.02 | 61 | 20.1 | |

| Trichomoniasis | 1 | 2.0 | 0.29 | 0 | – | – | 2 | 66.7 | <0.01 | 2 | 8.3 | 0.17 | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | – | 12 | 4.0 | |

| Vaginal condition | HPV16(n=9) | HPV18(n=5) | HPV45(n=2) | HPV31,33(n=1) | HPV52,58(n=2) | HPV66(n=4) | Other types(n=20) | Negative(n=104) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | p | n | % | ||

| Group 3Older than 50 years | Bacterial vaginosis | 2 | 22.2 | 0.27 | 1 | 20 | 0.35 | 0 | –– | – | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | – | 2 | 50 | 0.06 | 3 | 15 | 0.28 | 15 | 14.4 |

| Yeasts | 0 | –– | – | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | – | 1 | 100 | – | 0 | – | – | 1 | 25 | 0.17 | 0 | – | – | 8 | 7.7 | |

| Trichomoniasis | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | – | 0 | – | – | 2 | 1.9 | |

There is strong evidence that HPV infection is necessary, but not sufficient, for the development of cervical cancer. The main factor in cervical carcinogenesis is caused by a persistent hr-HPV infection, although others factors remain unclear. One of the factors that has become more important today is the microbiome that accompanies HPV infection37.

According to Gonzalez et al.24, the prevalence of hr-HPV infection in Argentinian women between 15 and 17 years of age, was 42.2%. In our study, 57.2% of patients in the 18–24-year age group had hr-HPV infection. In contrast, the prevalence in the 25–50-year-age group was 33.6% and, 29.3% in the age group over 50 years. When we analyzed the prevalence of different viral types according to age, we detected that in the group of women aged 18–24 years, the most prevalent viral type was HPV16, followed by HPV31 and HPV33. Similar results were reported by Orlando et al.55, who analyzed the prevalence of HPV in women aged 13–26 years in Italy, detecting that the most common viral types were HPV16 and HPV31. Likewise, de San José et al.13, reported that HPV16 was the most prevalent in this age group.

Hammer et al.26, described that the prevalence of HPV16 decreases by 5.7% for every 10-year increase in age. This aligns with our data, in which we detected that the group of women aged 25–50 years had a prevalence of HPV16 of 10.7%, while the group over 50 years old had a prevalence of 6.1%.

A U.S. study reported that in patients with H-SIL/SSC, the most prevalent viral type was HPV16 (25.6%)67. In Latin America and the Caribbean, a study analyzed the presence of HPV-DNA in 5500 cervical SCC and detected that HPV16 prevalence in female patients diagnosed with histological H-SIL/SSC was 46.5% in the entire region and 48.5% in Argentina10. Other studies in Argentina reported that the most prevalent HPV type was HPV16 on H-SIL/SCC2,3,42,46. In our study, the prevalence of HPV16 on H-SIL/SSC was 50% in the entire population and the prevalence across age groups was 63.6% in Group 1 and 43.8% in Group 2.

However, the prevalence of HPV16 in women with H-SIL/SSC varies across different continents. The HPV Information Center reported prevalence rates of HPV in different regions: Africa 27.1% (95% CI: 22.9–31.6), America 49.8% (95% CI: 48.9–50.6), Asia 36.4% (95% CI: 35.6–37.3), Europe 47.4% (95% CI: 46.8–48.1) and Oceania 50.3% (95% CI: 47.9–52.8)7. In fact, these data show that the epidemiology of HPV is quite similar in different regions of the world, although with some differences.

Yang et al.70 detected HPV16 in 28.3% of L-SIL. In our data, HPV16 was detected in 27% of L-SIL cases overall, with 30.4% in Group 1 and 26.5% in Group 2.

Regarding other high-risk viral types, the HPV Information Center reported that in H-SIL, the prevalence of HPV31 and HPV33 in the Americas was 11.7% (95% CI: 11.2–12.3) and 5.7% (95% CI: 5.3–6.1), respectively7. In our study, the prevalence of HPV31 and HPV33 was 6.8%. Similar results were reported by Ciapponi et al.10, who detected that the prevalence of HPV31 and HPV33 in Latin America was 8.0% (95% CI: 6.0–10.4) and 6.5% (95% CI: 4.7–8.5), respectively. In Argentina, Basiletti et al.3 detected that the prevalence of HPV31 was 19% and that of HPV33 was 6.9% in H-SIL cases.

The ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer7 reported that the prevalence of HPV52 and HPV58 in H-SIL cases in the Americas was 16.6% (95% CI: 15.9–17.2) and 14.5% (95% CI: 13.9–15.1), while in our study, the prevalence of HPV52 and HPV58 was 4.6%. Ciapponi et al.10 reported that the prevalence of HPV52 and HPV58 in Latin America was 4.9% (95% CI: 2.9–7.4) and 8.7% (95% CI: 6.0–11.9), respectively. In Argentina, Basiletti et al.3 detected a prevalence of 8.6% in HPV58 in H-SIL cases.

With respect to L-SIL, the HPV Information Center reported that the prevalence of HPV31 and HPV33 in the Americas was 6.5% (95% CI: 6.0–7.0) and 4.8% (95% CI: 4.4–5.3), respectively7. In our study, the prevalence of HPV31 and HPV33 in L-SIL was 14.3% in the entire population. Basiletti et al.3 reported a prevalence of 27.5% in HPV31 in L-SIL cases. Likewise, the same center reported that the prevalence of HPV52 and HPV58 in L-SIL in the Americas was 6.4% (95% CI: 5.9–7.0) and 6.0% (95% CI: 5.5–6.5)7, while in our study the prevalence of HPV52 and HPV58 was 7.9% in the entire population. Basiletti et al.3 reported a prevalence of 26.3% in HPV52 and 11.3% in HPV58 in L-SIL cases. These differences may be due to the fact that the reported prevalences include both Latin America and North America as a single population.

The microbiota is influenced by numerous factors, with ethnicity being the main intrinsic factor associated with the composition of the microbiome. Caucasian and Asian women show a higher prevalence of lactobacilli colonization compared to Hispanic and black women49,57.

Ravel et al.60 showed the apparent differences in the vaginal microbiome among ethnic groups and reported that the vaginal microbiome of North American women (Caucasian, African American, Hispanic, and Asian) was dominated by Lactobacillus (59%–89%). Among the four groups (Caucasian, African American, Hispanic, and Asian), the relative abundance of Lactobacillus among Hispanic and African American women was only 59.6% and 61.9%. However, in Asians and Caucasian women, the relative abundance of Lactobacillus was 80.2% and 89.7% respectively41. Verstraelen et al.68, analyzed 13 women from Belgium and found an abundance of L. crispatus and Lactobacillus iners. In another study, L. gasseri was the most predominant lactobacilli in Chinese women, with a higher prevalence in fertile women than in postmenopausal women73. Among the Japanese women, L. crispatus was the predominant species, followed by L. iners, similar to Caucasian and African Americans in North America74. Since an individual's microbiome is in part influenced by geography, diet, ethnicity, and degree of urbanization, it is important to know the specific microbiome composition in a specific geographical location27.

In Argentina, there are currently few publications that characterize the microbiome using next-generation sequencing. However, in our previous report, we detected an increase in vaginal microbiota imbalance in patients with H-SIL/SCC, especially in those aged 18–24 years23.

Cervical cancer is a long-standing disease, and there are stages prior to it during which the conditions of the cervical and vaginal environment are modified, such as vaginal acidity and the cytokine pattern that transitions from a proinflammatory pattern to a state of local immunosuppression.

The literature exploring the relationship between BV and HPV is consistent, with longitudinal studies demonstrating association of this condition with increased incidence of infection and decreased clearance of HPV39. In Brazil, Martins et al.44 conducted a review that reported an association between BV and HPV infection (OR=2.68; 95% CI: 1.64–4.40; p<0.001). A meta-analysis published by Gillet et al.23 in Belgium, demonstrated that the presence of BV increases the risk of developing a squamous intraepithelial lesion by 1.51 times (95% CI: 1.24–1.83; p<0.05), indicating a positive association between the two conditions. In China, Gao et al.19 detected a higher prevalence of L. gasseri and G. vaginalis in HPV-positive women compared to HPV-negative women. Similarly, Oh et al.54 in Korea, reported a predominance of Atopobium vaginae, G. vaginalis and L. iners, along with a reduction in L. crispatus, associated with a higher risk of intraepithelial lesions (OR 5.8; 95% CI: 1.7–19.4). They also described that the abundance of A. vaginae was associated with an increased risk of intraepithelial lesions (OR 6.6; 95% CI: 1.6–27.2). Furthermore, they reported a synergistic effect between A. vaginae, G. vaginalis and hr-HPV types, associated with a significantly higher risk of intraepithelial lesions (OR 34.1; 95% CI: 4.9–284.5). Maswanganye et al.45, in Africa, demonstrated that HPV-positive women exhibited lower levels of Lactobacillus and an increase in BV-associated species such as Gardnerella, potentially supporting HPV persistence.

Additionally, it has been proposed that the vaginal microenvironment and cytokine profile play a role in the generation of squamous intraepithelial lesions27,51. For example, Fusobacterium spp. infection could play a role in the development of an immunosuppressive microenvironment characterized by anti-inflammatory cytokines (Th2 cytokine profile), such as IL-4 and TGF-β1, in HPV-transformed cells, which would favor the evasion of the immune system and the persistence of infection39,51.

In our study, in Group 1, 54.2% of HPV16-infected patients had associated BV. This may be because HPV infection can alter vaginal mucosal metabolism, host immunity, or both, resulting in changes in the structure of the vaginal ecosystem27,29,65. Lee et al.38, reported that HPV-infected vaginal epithelia show a decrease in glycogen production, which is a source of energy for lactobacilli and responsible for the decrease in vaginal pH. Proinflammatory cytokines, reactive oxygen species, viral DNA integration and chronic inflammation that occur in HPV infection can cause changes in the vaginal mucosal environment, resulting in changes in the vaginal microbiota38.

In Group 2, BV was associated in 34.7% with HPV16 and 26.5% with other types. According to Rodriguez-Cerdeira et al.63, there was an association between patients with bacterial vaginosis and viral types HPV16, HPV31 and HPV33.

A recent meta-analysis reported that a distinct microbial composition was observed in hr-HPV-positive women, including Bifidobacteriales, Bifidobacteriaceae, Aerococcus, Aerococcaceae, Coriobacterales, Coriobacteriaceae, Fusobacteriales, Fusobacteria, Actinobacteria, Gardnerella, G. vaginalis, Atopobium, Atopobium vaginae, Leptotrichiaceae, and Sneathia. Among these, Coriobacterales, Actinobacteria, Fusobacteria, Fusobacteriales, Gardnerella, G. vaginalis, Atopobium, and Atopobium vaginae were significantly associated with BV, indicating a distinct microbiome profile in HR-HPV cases characterized by a higher prevalence of BV-associated bacteria45. These results are supported by Mitra et al.49, who reported in the United Kingdom, higher levels of Sneathia sanguinegens, Anaerococcus tetradius, and Peptostreptococcus anaerobius in patients with H-SIL compared to those with L-SIL. These authors also described that CST IV was associated with increased disease severity (10% in patients without lesions, 21% in L-SIL, 27% in H-SIL and 40% in cervical cancer), whereas CST I was negatively associated with disease severity49. These findings are further supported by Brotman et al6. in USA, who reported a higher proportion of vaginal samples from HPV-positive patients with microbiomes dominated by L. iners (CST III, 72%) and CST IV (71%). Another study showed that patients infected with hr-HPV and bacterial vaginosis had increased E6/E7 mRNA expression31.

In the cohort studied, all age groups had a higher prevalence of BV than yeasts and trichomoniasis. These findings were also reported by Abdul-Aziz et al.1, in Yemen, who reported a prevalence of BV of 27.2%, yeasts of 6.8%, and trichomoniasis of 0.9% in patients of reproductive age, with higher prevalence in patients under 25 years of age: 39.6% for BV and 9.9% for yeasts. However, given that the prevalence of these conditions varies from one country to another, Bucemi et al.8, in Argentina reported a prevalence of BV of 25.6% and yeasts of 17.4%, while Kamara et al.34, in Jamaica described a prevalence of BV of 44.1%, yeasts of 30.7% and, trichomoniasis of 18%.

Candidiasis is the most frequent fungal infection of the lower genital tract, although in most cases it is an asymptomatic colonization. However, there are some highly virulent yeast species that cause degradation of the vaginal epithelial basement membrane with consequent endogenous invasion and accompanying inflammatory response. Such damaged epithelium favors the entry of other STIs, such as HPV. These findings were observed by Kero et al.35, who demonstrated that yeast infection may be a risk factor for the acquisition of HPV infection, but not for viral persistence. In our study, 34.7% of patients aged between 25 and 50 years, with other types hr-HPV were associated with yeast infection. A recent meta-analysis showed that the combined OR of yeast infections and hr-HPV infection was 0.91 (95% CI: 0.54–1.51). There was no significant difference in the prevalence of yeast infections between hr-HPV positive and negative individuals (Z=0.37, p=0.71)71. These results were similar to those reported by Wang et al.69, who detected no association between vulvovaginal candidiasis and HPV infection. In Group 3, due to the small number of patients in the sample, the relationship between BV, yeasts and the different types of hr-HPV could not be objectified.

In our study population, we found a low prevalence of trichomoniasis (less than 4%). This low prevalence is due to the fact that both symptomatic and asymptomatic populations were studied. Similar findings were reported by Abdul Aziz et al.1, who described a prevalence of trichomoniasis of 0.9%. In contrast, Kamara et al.34, reported a prevalence of trichomoniasis of 18%. These disparities in prevalence could be due to different socioeconomic conditions and ethnic differences.

Regarding the relationship between HPV infection, we did not detect any association between HPV and trichomoniasis, even though it should be noted that the prevalence of trichomoniasis in the study population was very low. These findings are consistent with Yang et al.70, who demonstrated that the combined OR of T. vaginalis and hr-HPV infection was 1.69 (95% CI: 0.97–2.96). There was no significant difference in the prevalence of T. vaginalis between hr-HPV positive and negative individuals (Z=1.86, p=0.06). However, Wang et al.69, Heikal et al.28, and Mei et al.48, reported a statistically significant association between T. vaginalis and HPV infection.

ConclusionsA high prevalence of hr-HPV infection was detected in the 18–24-year age group. HPV16 was the most prevalent type in both the 18–24 and 25–50-year age groups. BV was the most prevalent condition in all age groups studied. HPV16 was the most prevalent in the 18–24-age group with bacterial vaginosis. HPV16 was the most prevalent type in both H-SIL/SCC and L-SIL groups. It is important to investigate the presence of microbiota imbalance in patients with HPV, as the increased prevalence of BV could favor persistence and progression to cervical cancer.

Ethical approvalThis study was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee and all patients gave informed consent.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors state that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingThis manuscript was supported by an Argentinian government agency, project UBACYT-20020150200194BA (Universidad de Buenos Aires). No external funding was used in the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.