Protothecosis is an infectious disease caused by microalgae of the genus Prototheca. Prototheca can be found in soil and water and transiently colonize animals. Cutaneous protothecosis can involve not only the skin but also the underlying subcutaneous tissue and lymph nodes. This can lead to clinical signs and a microscopic tissue image that closely resembles a fungal infection. Treatment typically involves antifungal medications. We report the first case of fatal disseminated protothecosis caused by Prototheca wickerhamii in the city of Rosario, Argentina in a 5-year-old female poodle dog. The dog exhibited ocular signs of uveitis and lymphadenitis. To reach a clinical and etiological diagnosis, imaging studies, routine laboratory tests and serological tests were performed. A mycological analysis was conducted on the material obtained by puncturing three lymph nodes. Additionally, morphological, metabolic, and molecular analyses were performed. Antifungal susceptibility testing was also conducted using broth microdilution and diffusion methods. Phenotypic, metabolic, and sequencing techniques identified the isolated organism as P. wickerhamii. This isolate displayed susceptibility to amphotericin, variable susceptibility to itraconazole and voriconazole, and resistance to fluconazole and caspofungin. The frequent presence of pets in our homes highlights the need for a more comprehensive diagnostic approach. This is important because, from a public health perspective, dogs could serve as indicators of algal presence in the environments they frequently share with humans.

La prototecosis es una enfermedad infecciosa causada por microalgas del género Prototheca. Estas algas pueden colonizar animales de forma transitoria. La prototecosis cutánea puede afectar no solo la piel, sino también el tejido subcutáneo subyacente y los ganglios linfáticos. Esto puede conducir a un cuadro clínico y microscópico en secciones de tejido que se asemeja mucho a una infección fúngica. Generalmente, el tratamiento involucra medicamentos antimicóticos. Presentamos el primer caso de prototecosis diseminada fatal producido por Prototheca wickerhamii en Rosario, Argentina, en una perra caniche de 5años. La perra mostró signos oculares de uveítis y linfadenitis. A fin de arribar a un diagnóstico clínico y etiológico, se realizaron estudios de imágenes, pruebas de laboratorio de rutina, pruebas serológicas y análisis micológico del material obtenido por punción de tres ganglios linfáticos. Posteriormente, se llevó a cabo el estudio morfológico, metabólico y molecular del microorganismo aislado y se efectuaron pruebas de sensibilidad a antifúngicos usando métodos de microdilución y difusión. Las técnicas fenotípicas, metabólicas y de secuenciación identificaron al organismo como P.wickerhamii. Este fue sensible a la anfotericina, de sensibilidad variable al itraconazol y al voriconazol, y resistente al fluconazol y a la caspofungina. La frecuente presencia de mascotas en nuestros hogares subraya la importancia de un enfoque diagnóstico integral, considerando que, para la salud pública, el perro podría actuar como centinela de la presencia del alga en el ambiente que frecuenta y comparte con humanos.

The genus Prototheca encompasses unicellular, aerobic, spherical algae with diameters ranging from 3 to 30μm. These organisms are characterized by structures known as theca, mother cells, or spherules (sporangia), differentiated by their morphology. Asexually, they can produce 2–16 daughter cells (endospores), which may resemble a morula7,25. These organisms are widely distributed in the environment and can be isolated from various animal reservoirs and food sources. They can also exist saprophytically in aqueous environments containing decomposing plant material. From these and other environmental sources, Prototheca microalgae may enter and pass through the human and animal gastrointestinal tract and enter sewage21. Therefore, infection by Prototheca in humans and animals typically occurs through contact with these aforementioned sources or reservoirs44. Microorganisms may also enter through open wounds, trauma, surgical wounds, and insect bites, causing opportunistic infections. Although it is not transmitted from person to person, special care must be taken to avoid contact with contaminated sources. Risk factors include surgery, diabetes mellitus, treatment with immunosuppressants, kidney transplant, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and chemotherapy or radiotherapy. According to the Valencian Institute of Microbiology (IVAMI – Instituto Valenciano de Microbiología)12, the incubation period of the disease can range from weeks to months. As of 2012, approximately 160 cases have been reported worldwide, with the most common presentation being cutaneous39. In 2014, a series of cases of cutaneous localization in immunocompromised patients was described in Mexico28,43. In 2017, 211 cases of protothecosis were documented, and today, this alga is increasingly recognized as an emerging pathogen affecting both human and animal populations40. Of the postulated species within the genus, five (Prototheca wickerhamii, Prototheca blaschkeae, Prototheca cutis, Prototheca miyajii, and Prototheca zopfii) are described as opportunistic pathogens of humans and animals. P. wickerhamii has the broadest host range and includes cats, dogs, horses, buffaloes, and goats, in addition to humans. It is important to note that the genus Prototheca, established by Krüger in 1894, has undergone significant revisions and continues to undergo scrutiny as more phenotypic, chemotaxonomic, and molecular data become available. Consequently, there may be controversial information regarding its taxonomy. In an attempt to clarify this situation, Jagielski et al. proposed a new classification for the genus based on the evaluation of the mitochondrial cytochrome B (cytB) gene in 2019 and reviewed the taxonomy and nomenclature of a set of Prototheca strains conserved in the main deposits of algae cultures from around the world13,44. By applying cytB gene analyses, genotypes 1 and 2 of P. zopfii were elevated to species status in the forms of Prototheca ciferrii and Prototheca bovis, respectively. Furthermore, five new species were proposed: Prototheca cerasi, Prototheca cookei, Prototheca pringsheimii, Prototheca xanthoriae and the redefined P. zopfii. In addition, a new species, Prototheca paracutis, has also been recently described17. Currently, only six Prototheca species (P. blaschkeae, P. bovis, P. cutis, P. miyajii, P. ciferrii and P. wickerhamii) have been clearly implicated as human and animal pathogens13,24.

In human hosts, P. wickerhamii mainly affects the skin and mucous membranes, and P. cutis and P. zopfii are responsible for systemic infections. P. wickerhamii has been recognized as the main species causing systemic infections in immunocompromised hosts6,9,19,33.

In animals, the most prevalent form of protothecosis is bovine mastitis. Acute infections result in granulomatous mastitis, whereas chronic progression is associated with increased somatic cell counts and reduced milk production due to the damage inflicted on the udder21. Prototheca also represents a potential zoonotic risk, as they persist after the pasteurization of milk due to their heat-resistant nature26. After mastitis in dairy cows, canine protothecosis is the second most prevalent form of protothecal disease in animals7.

Dogs typically suffer from disseminated infections that usually begin with chronic bloody diarrhea followed by typical ocular and neurological signs such as ataxia, blindness, deafness, or seizures1,3,37,42. Less commonly, dogs can develop focal or multifocal localized cutaneous disease following penetrating trauma3,29. Skin lesions can occur as the sole clinical sign of disease or can be accompanied by gastrointestinal, neurological, or ophthalmic signs10.

Prototheca organisms exhibit tropism in the eye, central nervous system, bone, kidneys and myocardium, where algae may spread from the intestinal tract or other primary sites of infection27,37, but may also infect other organs, such as the lungs, spleen, liver, tongue, skin, and surface lymph nodes. In contrast to human cases, canine protothecosis has mainly been caused by P. bovis. Infections due to P. wickerhamii seem to be rarer. The prognosis for patients with disseminated protothecosis is poor despite treatment, with a mortality rate of up to 75%27,32,37.

Although microscopic identification is not definitive, micromorphological differences can be observed between the size and number of endospores within sporangia for different species15. The histological lesions typically present as granulomas or pyogranulomas, characterized by abundant necrosis and minimal inflammatory infiltration30.

Within these lesions, the organisms are often numerous and exhibit various morphologies, including spherical, rounded, oval, or polyhedral shapes31. When they mature, they have between two and more than ten polyhedral endospores that give them a characteristic carriage wheel appearance. They stain slightly basophilic with hematoxylin–eosin and they are intensely positive for PAS (periodic acid Schiff) and Grocott. Although P. wickerhamii is spherical with rounded central endospores and this feature has been defined as “morula or raspberry form”2,11, a differential diagnosis can be made with other microorganisms. This is because the lack of endospores, characteristic of Prototheca, can be confused with the structures of Blastomyces dermatitidis, Cryptococcus spp., Paracoccidioides spp., some stages of Coccidioides spp. and Pneumocystis jirovecii, among others. Therefore, the diagnosis of infection of the Prototheca species by histopathology is complex9. Therefore, the certainty of diagnosing P. wickerhamii depends on the expertise of the microbiologist who identifies its macro- and microscopic morphology, supplemented with physiological and molecular tests for definitive identification. These methods are crucial for distinguishing this species and guiding proper treatment in clinical cases.

The therapeutic approach is performed using antifungal compounds, typically azoles and amphotericin B (AMB)32,42. Although surgical resection of the affected areas is an important strategy combined with supportive antifungal therapy for treating feline protothecosis8, in canine protothecosis, the prognosis of improvement or cure is poorer despite the establishment of treatment42.

With regard to susceptibility to antifungal compounds, no guidelines have been issued by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) to perform and interpret antifungal susceptibility tests for this type of microorganism. Therefore, these cases were resolved using the basic documents M27-A3 and M44-A2 for Candida spp.4,5. Studies by Marques et al. have indicated that Prototheca species are sensitive to AMB and nystatin29. AMB, in particular, is widely used to treat Prototheca infections in humans22 and has shown very good activity, with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) ranging from 0.09 to 3.2μg/ml34. Other studies have reported increased activity of voriconazole (VCZ) (MIC 90=0.5μg/ml) compared with AMB (MIC 90=1μg/ml) in P. wickerhamii strains isolated from humans22. In general, the literature agrees that the Prototheca species are susceptible to AMB and have variable susceptibility to azoles such as fluconazole (FCZ), itraconazole (ITZ) and VCZ9,18,20.

In this study, we present a case involving a 5-year-old poodle female dog from the city of Rosario, Argentina, whose owner sought consultation due to her unusual eye appearance. The owner also reported that the dog had access to an outdoor area, had contact with a humid environment, attempted to hunt pigeons, and occasionally encountered rats.

Material and methodsSamples from a 5-year-old poodle female dog were collected from a patient whose owner sought consultation due to the pet's unusual eye appearance. The owner reported that the dog had access to an outdoor area, had contact with a humid environment, attempted to hunt pigeons, and occasionally encountered rats. Abdominal ultrasound was performed. A complete blood laboratory including an ionogram and a proteinogram was also conducted, as well as an immunochromatography RK39 assay to detect visceral leishmaniasis. Toxoplasma gondii serology by indirect immunofluorescence was carried out. Antibodies against Ehrlichia canis were tested by immunochromatographic methods. Hepatozoon canis, Babesia vogeli, Mycoplasma hemotropicos, Anaplasma platys, A. marginale and Ehrlichia canis were examined by optical microscopy using methanol-Giemsa staining.

Cytology of lymphonodules of the preescapular, popliteal, and submandibular locations was performed and methanol Giemsa-stained spreads were studied. Due to the structures observed in the spreads, routine mycological analysis of the samples from the ganglion puncture performed by fine needle aspiration (FNA was carried out in the laboratory of the Mycology Reference Center (Centro de Referencia de Micología: CEREMIC). The samples of the three lymph nodes were cultured in Sabouraud-glucose, Mycosel, Sabouraud-glucose-chloramphenicol at 28°C, Sabouraud-glucose, and blood agar at 37°C. Direct examinations of the samples were performed using lactophenol blue and May Grünwald Giemsa staining techniques. The isolates were identified by microscopy, automated phenotypic studies using Vitek® equipment (Biomerieux), and definitive identification with MALDI-TOF MS® (Biomerieux) and molecular speciation with the proposed polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based method targeting the mitochondrially encoded cytB gene marker14. For this purpose, genomic DNA was first extracted from pure fungal cultures in GYEP broth (2% glucose, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% peptone, Merck KGaA) and incubated for 24–48h at 37°C. Then, genomic DNA was isolated using phenol–chloroform–isoamyl alcohol extraction38, and PCR amplification was performed as previously described using primers CYTB_F1 (5′-GYG TWG AAC AYA TTA TGA GAG-3′) and CYTB R2 (5′-WAC CCA TAA RAA RTA CCA TTC WGG-3′)14. PCR products were purified using the PCR and DNA Fragment Purification KitTM (Dongsheng Biotech, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China) and bidirectionally sequenced using ABI BigDye Terminator v.3.1 (Macrogen Inc., Seoul, South Korea). The resulting nucleotide sequences were compared with curated sequences published in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank database. The nucleotide sequences were deposited in GenBank with accession number PP584668.

The susceptibility of the isolates to antifungal drugs was evaluated by microdilution in broth against AMB, FCZ, ITZ, posaconazole (PSZ) and VCZ (Sigma Aldrich, Argentina) following the guidelines of the CLSI M27-A3 Document5. Drugs were acquired as standard powders from their manufacturers or from Merck-Sigma-Aldrich (Argentina). AMB (Rosco®), FCZ (manufactured by Malbran Institute, Buenos Aires, Argentina), ITZ (Rosco®), and caspofungin (CFG) (Rosco®) were tested in solid media following the CLSI guidelines4.

ResultsAlthough upon clinical examination, the dog showed widespread adenomegaly, middle iliac lymphadenopathy was revealed by ultrasound. This study also showed diffuse hepatopathy, reactive spleen and cortical renal changes.

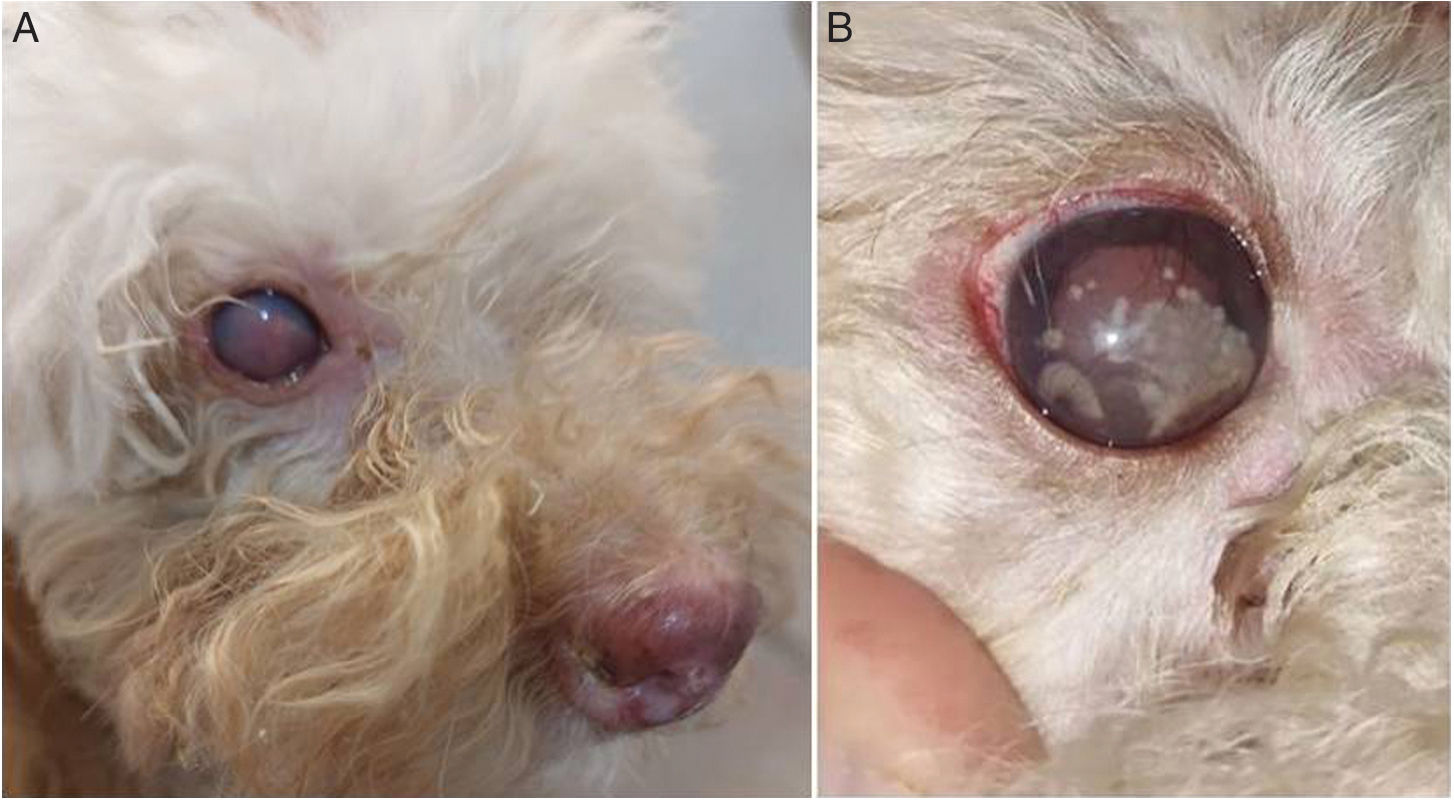

In the eyes, collections were observed in the anterior region of relatively rapid evolution and with a presumptive diagnosis of blindness. The lesions in the anterior chamber were described as white spots with scalloped edges that showed rapid evolution, which could be observed during the veterinary consultation for monitoring progress (Fig. 1). The diagnosis was pyogranulomatous uveitis in both eyes. In the routine laboratory, the proteinogram revealed hyperproteinemia (9.2g/dl; reference value: 5.7–7.5g/dl) with hyperglobulinemia (6.7g/dl; reference value: 2.4–4g/dl) at the expense of an increase in beta globulins (2.92g/dl; reference value: 0.5–1.3g/dl). Gamma globulins showed normal values (2.72g/dl reference value: 1.5–3.5g/dl). Albumin/globulins ratio was 0.3 (reference value: 0.6–1.1). Blood analysis revealed hypochromic normocytic anemia. The white series exhibited leukocytosis with neutrophilia, eosinophilia and regenerative left shift with toxic changes and cytoplasmic basophilia.

The ionogram values were sodium 147mEq/L and potassium 6.5mEq/l. Both serological tests and microscopic studies for the diagnosis of hemoparasites were negative.

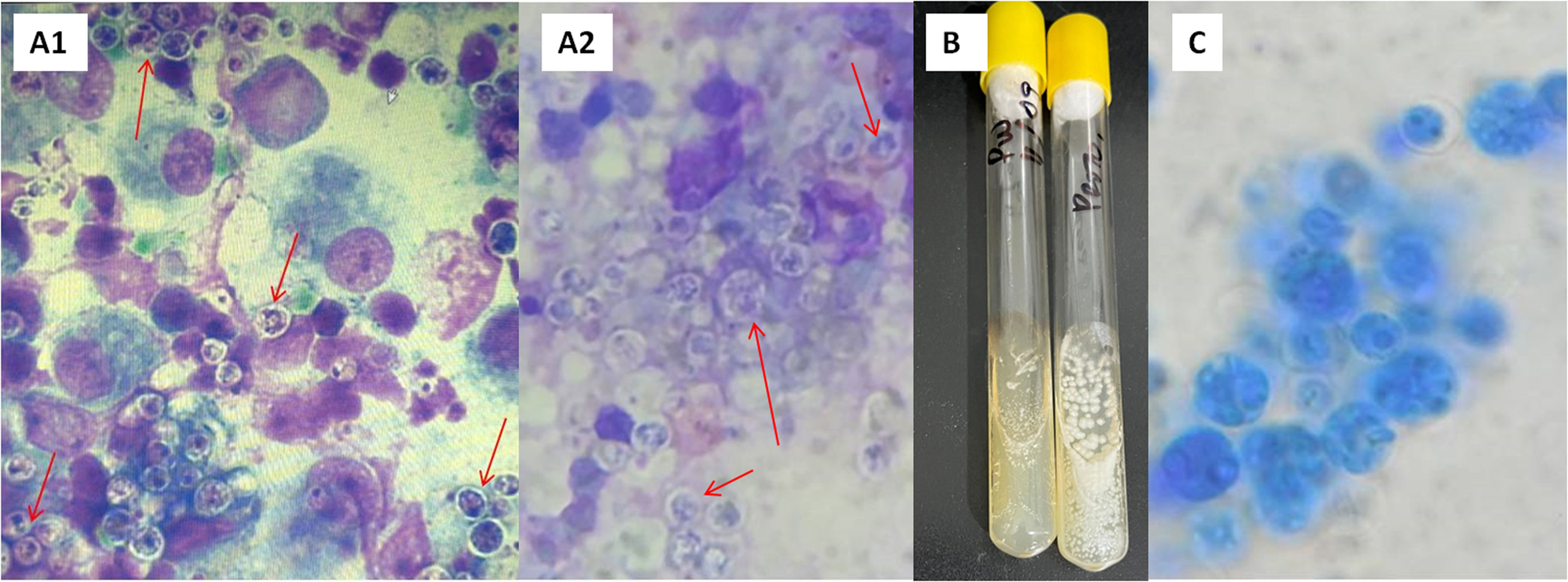

Based on the cytological analysis of the three ganglion samples, a heterogeneous population of mature and differentiated lymphoid cells was observed, with a moderate amount of plasma cells and a regular amount of lymphoblasts, polymorphonuclear neutrophils, eosinophils, a low number of mastocyte cells, and a large number of active macrophages with intense phagocytosis. In addition, round structures approximately 4μm in diameter with thick, non-staining walls were observed. These structures have internal septations forming small, wedge-shaped endospores arranged radially and molded into a morula-like pattern, suggesting the presence of fungal elements (Fig. 2A1).

(A) Structures with internal septa that form small endospores arranged in a morula-like pattern. (A1) Cytology of a submandibular lymph node sample stained with methanol-Giemsa. Optical microscope, 1000×. (A2) May Grünwald-Giemsa staining of submandibular lymph node sample. 1000×. (B) Macromorphology after three days of incubation in Sabouraud-glucose at 28°C. (C) Microscopic morphology observed in the culture at 28°C with lactophenol blue; spherules (sporangia) of different sizes are observed, 400×.

In the mycological analysis, direct examination of the ganglion samples using May Grünwald Giemsa staining (Fig. 2A2) and lactophenol blue, revealed the presence of spherules (asexual sporangia) with endospores. After three days of incubation (Fig. 2B), the microorganism from all samples studied grew with white yeast-like morphology at 28°C and 37°C, showing proper development in the culture media seeded, with the exception of Mycosel. Microscopic examination of this isolate using lactophenol blue (Fig. 2C) also revealed the presence of spherules with endospores. The Vitek system identified the microorganism as P. wickerhamii with a very good level of confidence and a probability of 93%. The matrix assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) test also identified a strain with a confidence level of 99.9%. The similarity of the nucleotide sequences of the cytB gene obtained here to those obtained from the GenBank database confirmed with high bootstrap support (1000 replicates) that the isolate was P. wickerhamii. The neighbor-joining method of phylogenetic analysis was used for determining genetic relationships. The best model of evolution was estimated using the JModelTest software considering both the Bayesian and Akaike information criteria and the phylogenetic tree was constructed using the PhyML 3.0 software.

The antifungal susceptibility evaluated by the microdilution broth test showed the following MIC values: 0.125μg/ml for AMB, 1μg/ml for ITZ, 0.5μg/ml for PSZ, 0.25μg/ml for VCZ and ≥64μg/ml for FCZ. By diffusion in agar, the following growth inhibition diameters were obtained: AMB=30mm, ITZ=25mm, FCZ and CFG ≤10mm. However, it is important to note that there are currently no reference values for an unequivocal interpretation of the results found.

The dog was initially treated empirically with enrofloxacin (a second-generation quinolone), an antibiotic usually used for prophylaxis, since the microbiological diagnosis was not yet known and the blood count showed leukocytosis with neutrophilia, and a regenerative shift to the left with toxic changes. An appropriate treatment for the infectious disease could not be established because the dog died before the diagnosis was confirmed, due to respiratory complications, including tachypnea attributable to neurological failure.

DiscussionThe literature reveals that the first worldwide report of canine protothecosis occurred in the United States in 1969. Subsequently, the disease was diagnosed in dogs from various regions of the world, including England, Spain, Greece, South Africa, Australia, Japan, and Brazil35,37. P. zopfii was detected in contaminated waters in Argentina in 200241 and has been known to cause mastitis in cows in our country. According to a literature review, this is the second case of canine protothecosis reported in Argentina, the first case caused by P. zopfii was published in 2017 in the city of Mar del Plata36, and the first case caused by P. wickerhamii in the city of Rosario.

As described above, Prototheca is a genus of colorless and aclorophilic algae. This biological particularity gives them unique clinical relevance since, despite their algal origin, Prototheca is the only genus of the family Chlorellaceae recognized as a causative agent of opportunistic infections in both humans and animals. These microorganisms, which are generally associated with environmental pollution, have been identified as pathogens in various clinical scenarios, highlighting their ability to cause diseases ranging from skin infections in immunocompetent hosts to severe systemic infections in immunocompromised individuals; an outbreak of sepsis caused by these organisms was described in an oncology unit in 201816. On the other hand, although Prototheca infections in domestic animals are considered rare in veterinary practice, they represent a unique clinical challenge when making the diagnosis. Canine protothecosis is the second most prevalent form of protothecosis in animals after dairy cow mastitis10.

In this study, we describe a fatal case of disseminated protothecosis caused by P. wickerhamii in a poodle dog with ocular signs of uveitis and lymphadenitis. Although the typical manifestations of protothecosis include hemorrhagic diarrhea and neurological signs, the dog did not exhibit any these symptoms. Even though the source of infection in the dog is not known, it should be noted that the dog had contact with pigeons and a rat. The detection of Prototheca in pigeon crop and rat feces suggests its potential role as a vector in the spread of microalgae among different animal groups and environments21.

It is important to consider that, routinely, diagnosis is made by isolating this microorganism from an ocular puncture or enucleation, for which the patient must undergo surgery, or by making a postmortem diagnosis. In our case, the diagnosis could be achieved by performing nodal puncture, which is a noninvasive and safe technique for the patient.

In this study, direct microscopic examination of the nodal puncture material allowed a presumptive diagnosis since asexual sporangia containing endospores were clearly differentiated and correlated with complementary and confirmatory diagnostic studies. This morphological peculiarity highlights the importance of thorough microscopic examination by a microbiologist, who will then perform more complex and specific identification studies to confirm the genus and species of the isolate. The automated Vitek® system, which analyzes metabolic properties as well as protein profiles using MALDI-TOF® technology, provides significantly sensitive and specific information that is highly reliable for routine diagnostic tasks. Wherever sequencing of these microorganisms is available, its implementation is very important to continue expanding the information available in databases such as GenBank.

Molecular techniques complement and confirm the identification provided by other low-resolution methodologies. As proposed in the literature, the use of the cytB gene as a molecular marker provides a higher resolution compared to conventional rDNA markers, representing the most efficient barcode for Prototheca microalgae40.

The Prototheca species has been tested against a wide range of antimicrobial agents and has shown extremely variable in vitro susceptibility10,23. However, the lack of correlation between in vitro and in vivo susceptibility is typical of this genus. In dogs, despite the availability of a wide range of antimicrobial agents, the disease often has a poor prognosis, mainly if it presents as a disseminated clinical form and if the diagnosis is not made early37. In this study, the observation of CFG resistance is not surprising since, considering that the majority of polysaccharides in the cell wall of this genus bind β-1,4 instead of β-1,3, it is expected that echinocandins that inhibit the enzymes involved in the synthesis of β-1,3 glucan junctions are generally ineffective24.

This research presents a clinical case with an unusual finding of Prototheca in a pet, highlighting the uniqueness and importance of early detection of this pathogen in the veterinary context. Through a detailed analysis of this case, we sought to broaden our understanding of the incidence, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and therapeutic options associated with infections in animals, highlighting the relevance of considering this pathology in the spectrum of possible diagnoses in veterinary clinical practice, and its impact on health when not diagnosed in time.

ConclusionsIn this work, we highlight the novelty of diagnosing using minimally invasive procedures, avoiding major surgeries, which are usually routine in these cases. This study also shows the importance of an early diagnosis, as well as the interdisciplinary work required to achieve it, in order to establish appropriate treatment.

Conflict of interestNone declared.