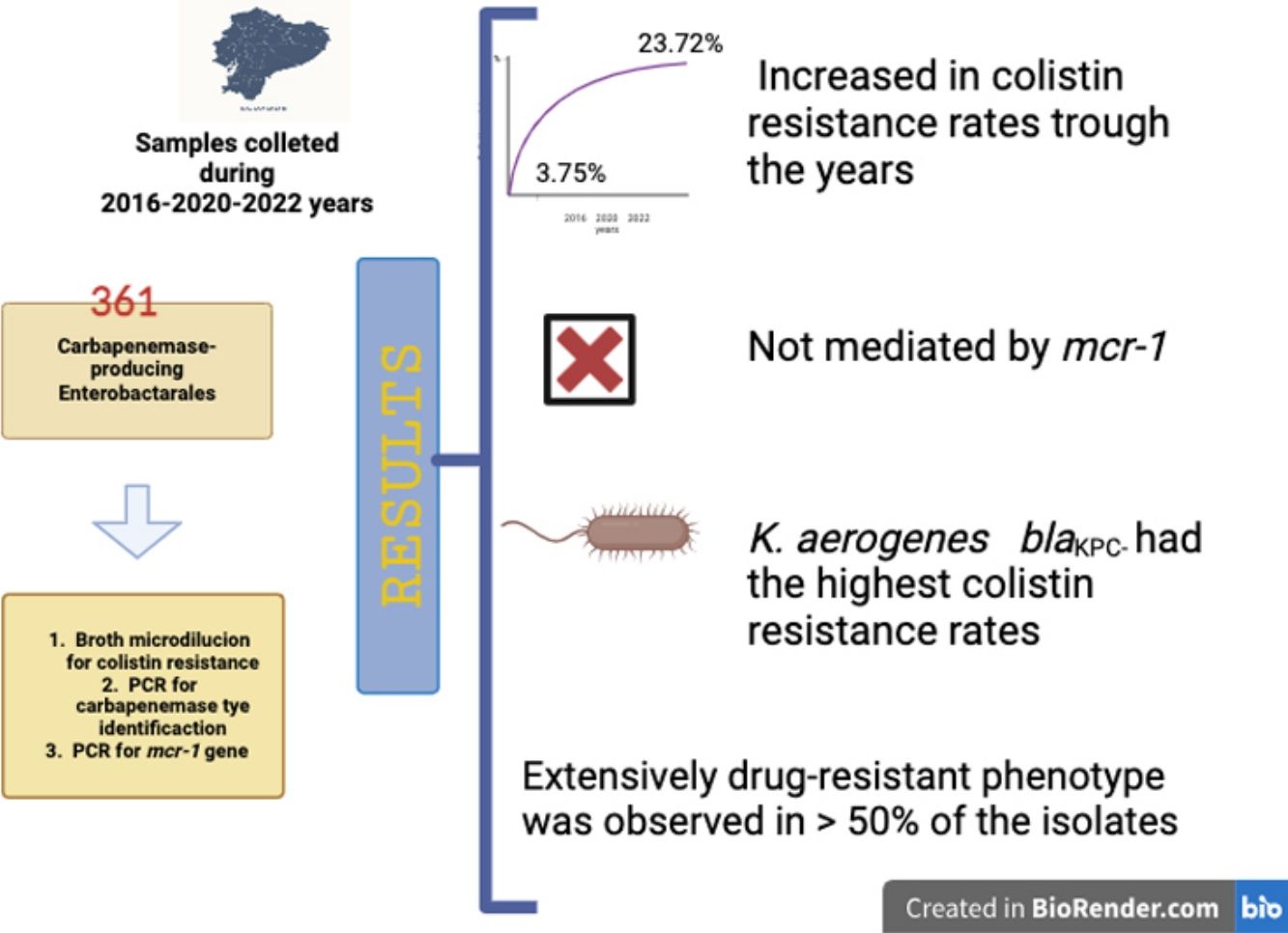

Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales (CPE) have increased in the last decade. In low-income countries, colistin is considered a last resort antimicrobial to treat CPE infections, whose most worrisome mechanism of resistance is MCR-1 production. This study aims to understand the epidemiology of colistin resistance in CPE in the region, through the surveillance of the mcr-1 gene in CPE isolates in Ecuador. A total of 361 CPE isolates were collected across three periods, from 2016 to 2022. Colistin resistance was assessed using the broth microdilution method and the most frequent carbapenemase-encoding genes and the mcr-1 gene were studied. Colistin resistance rate increased from 3.76% to 23.74% during the study period. The mcr-1 gene was not identified in any of the isolates studied and Klebsiella pneumoniaeblaKPC was the most prevalent microorganism (n=322; 89.20%). In conclusion, colistin resistance increased in CPE in Ecuador and was not mediated by the mcr-1 gene. Our results highlight the need to closely monitor national politics on antimicrobial resistance under the One Health Approach.

Este estudio tuvo como objetivo comprender la epidemiología de la resistencia a la colistina en Enterobacterales productores de carbapenemasas (EPC) en la región, a través de la vigilancia del gen mcr-1. Para ello se estudiaron 361 aislados de EPC de origen clínico obtenidos en Ecuador en tres momentos diferentes de los años 2016, 2020 y 2022. Se estudió la resistencia a colistina por microdilución en caldo y se identificaron los genes de las carbapenemasas más frecuentes y el gen mcr-1. Se observó un incremento en la resistencia a colistina del 3,76% al 23,74% durante el período estudiado. No se identificó el gen mcr-1 en ninguno de los aislados analizados; Klebsiella pneumoniae blaKPC fue el microorganismo más prevalente (89,20%). Nuestros hallazgos demuestran el incremento de la resistencia a colistina en EPC aislados en Ecuador no mediado por el gen mcr-1, lo que resalta la necesidad de ajustar las políticas nacionales para combatir la resistencia antimicrobiana.

.

Multidrug resistance (MDR) in gram negative bacilli has dramatically increased in the last decades, especially in Enterobacterales, becoming a serious public health concern. A predictive statistical model indicated that antibiotic resistance was responsible for 4.95 million deaths globally, with the highest burdens in low-resource settings6.

Although novel antibiotics have been developed in the last five years, their limited availability and high costs restrict their use in countries with low economic resources. This situation has forced the employment of less effective therapeutic schemes, which include colistin and/or tigecycline, even though they have demonstrated lower survival rates5.

Colistin is a drug whose use rebounded along with the emergence of resistance to carbapenems in gram negative bacilli in the 1990s. Its resistance is primarily due to mutations in the gene(s) that code for lipid A, but the emergence of plasmid resistance mediated by mcr genes has been described since 2015. Currently, ten variants of this gene have been described, being mcr-1 variant the most prevalent11.

In Ecuador, data regarding colistin resistance in carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales (CPE) is scarce. The mcr-1 gene was detected in Ecuador in 2016 and most publications involved isolates from animals or environmental sources4. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in our country to gather information about the presence of colistin-resistant in carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales (CR-CPE) in clinical samples.

To understand the epidemiology of colistin resistance in the region, this study aims to monitor the mcr-1 gene in CR-CPE in Ecuador, during three time periods from 2016 to 2022.

A retrospective cross-sectional study was carried out with previously characterized CPE isolates belonging to the microbiological culture collection from the “Sosegar Laboratory”. Isolates were obtained from different research projects and approved fundings during three different periods (2016, 2020 and 2022). All the samples were collected as consecutive cases. In the first period, rectal swabs and their clinical samples were collected from patients in private and public intensive care units in Guayaquil (for logistic purposes only rectal swabs were collected for further analysis); in the remaining two periods, clinical samples were collected from patients admitted to different public and private hospitals from Quito, Guayaquil, and Cuenca. Different approaches were applied depending on the funding provided. These cities are the most populated and economically important metropolises in Ecuador, accounting for 5095691 inhabitants (https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/censo-de-poblacion-y-vivienda/).

Data about inclusion criteria, type of hospital and samples included, and permissions from the ethics committee are detailed in Supplementary Table No. 1.

Carbapenemase production was previously assessed using the modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM) (document M100-S31) and molecular identification of the carbapenemase gene involved was detected by a multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR), including the blaKPC, blaNDM, blaOXA-48, blaVIM, and blaIMP genes9. Only one isolate per patient was included and Enterobacterales with intrinsic colistin resistance were excluded.

All isolates studied were stored in 20% skim milk (Oxoid, United Kingdom). Their viability and purity were checked in MacConkey agar (16–18h; 35°C) (Becton-Dickinson, England). Identification was confirmed using the Vitek® 2 Compact System (GN-Card) (BioMérieux, France) and conventional tests (motility, oxidase, and gram stain).

Colistin resistance was determined using agar dilution with a unique concentration of 3μg/ml following the methodology previously described14. Colistin sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich. Code C2700000. Batch 3.0) and Mueller-Hinton Agar (Becton-Dickinson, United Kingdom) were used. All isolates categorized as resistant by agar dilution were confirmed using colistin broth microdilution (CBM) to obtain the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC). The concentration range used was 0.5–4μg/ml and MIC values ≥4μg/ml were considered resistant according to the CLSI breakpoint document (M100-S32). A previously described PCR protocol for detecting the mcr-1 gene was used10. MCR-1 Clinical Strain Z&Z1409 was used as quality control strain.

Susceptibility tests for ciprofloxacin, amikacin, gentamicin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, tigecycline, ceftazidime/avibactam and meropenem/vaborbactam were performed using disk diffusion according to CLSI guidelines (document M100-S32). Non-susceptible phenotypes for ceftazidime/avibactam and tigecycline obtained by disk diffusion were confirmed using the agar diffusion method to obtain MIC values. Liofilchem Etest Strips (Liofilchem, Italy) were used, and the commercial methodology was followed. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) breakpoints were used for tigecycline (https://us05web.zoom.us/j/5164577177?pwd=Rkt5RUY5ODYvSHI3YmhHRVdFQ2Ywdz09).

Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 2785, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603 and E. coli AR Bank #0349 were used for quality control.

An extensively resistant (XDR) phenotype was defined as a CR-CPE isolate exhibiting additional resistance to at least one of the aminoglycosides tested, as well as to ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

During the study period, three hundred and sixty-one CPE isolates were included. The isolates were more frequently obtained in 2016 and 2020, with values of 36.8% (n=133/361) and 46.8% (n=169/361) respectively. Only 59 (16.3%) isolates were received in 2022. Rectal swabs were the predominant processed sample (42.4%; n=153/361), followed by respiratory (15.8%; n=57/361), blood (14.7%; n=53/361) and urine (10.3%; n=37/361) samples.

K. pneumoniae was the prevalent microorganism observed (n=322; 89.2%) followed by Klebsiella aerogenes (n=17; 4.7%), Enterobacter cloacae (n=11; 3.1%), E. coli (n=9; 2.5%) and Klebsiella oxytoca (n=2; 0.5%).

The total rate of colistin resistance in CPE was 20.8% (n=75/361). CR-CPE increased during the three time periods studied. A value of 3.8% (n=5) was observed in 2016, followed by 33.1% (n=56/169) in 2020 and 23.7% (n=14/59) in 2022.

The microorganism with the highest CR observed was K. aerogenes 52.9% (n=9), followed by K. pneumoniae 20.2% (n=65) and E. cloacae 9.1% (n=1). CR was not found in any of the E. coli or K. oxytoca isolates studied.

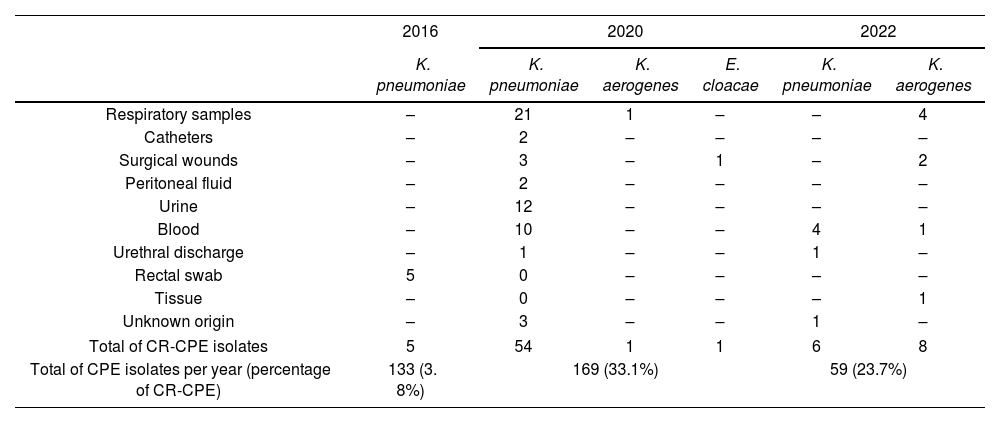

The highest prevalence of CR-CPE was found in respiratory samples (50.9%, n=57). Table 1 depicts the CR proportion of CR-CPE found in the samples according to the microorganisms involved.

Colistin resistance in carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales according to clinical samples.

| 2016 | 2020 | 2022 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K. pneumoniae | K. pneumoniae | K. aerogenes | E. cloacae | K. pneumoniae | K. aerogenes | |

| Respiratory samples | – | 21 | 1 | – | – | 4 |

| Catheters | – | 2 | – | – | – | – |

| Surgical wounds | – | 3 | – | 1 | – | 2 |

| Peritoneal fluid | – | 2 | – | – | – | – |

| Urine | – | 12 | – | – | – | – |

| Blood | – | 10 | – | – | 4 | 1 |

| Urethral discharge | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | – |

| Rectal swab | 5 | 0 | – | – | – | – |

| Tissue | – | 0 | – | – | – | 1 |

| Unknown origin | – | 3 | – | – | 1 | – |

| Total of CR-CPE isolates | 5 | 54 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 8 |

| Total of CPE isolates per year (percentage of CR-CPE) | 133 (3. 8%) | 169 (33.1%) | 59 (23.7%) | |||

The blaKPC gene was predominant in the CPE studied (n=353; 97.8%), blaNDM (n=7; 1.9%) and blaOXA-48 (n=1; 0.3%) were also observed. The blaNDM gene was detected in K. pneumoniae (n=5), K. aerogenes (n=1) and E. cloacae (n=1) while blaOXA-48 was present only in E. coli. All the CR isolates harbored the blaKPC gene and the mcr-1 gene was not detected in any of the CR-CPE isolates studied.

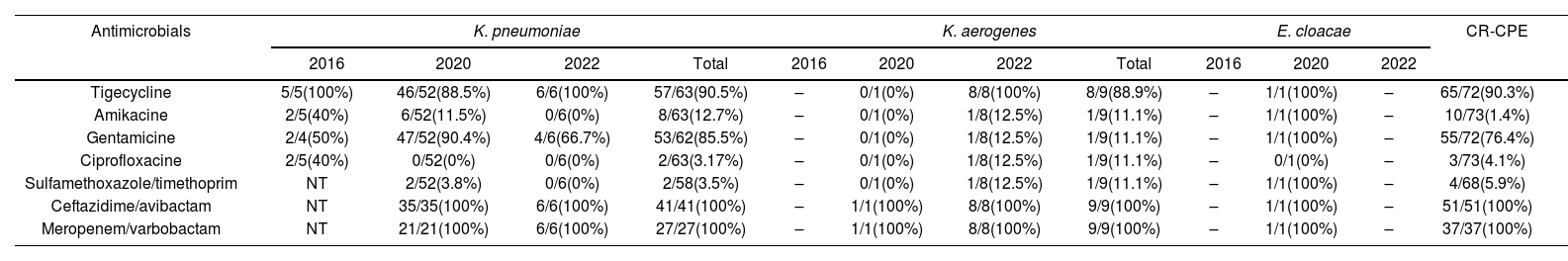

A high frequency of co-resistance to other antimicrobials was observed in CR-CPE. Only ceftazidime/avibactam (51 isolates tested) and meropenem/vaborbactam (31 isolates tested) maintained 100% susceptibility. Tigecycline also remained susceptible with a rate of 90.4% (n=66/73 tested) in CR-CPE. Susceptibility rates of CR-CPE to the antimicrobials tested are detailed in Table 2. Supplementary data on the susceptibility profile of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales is included in Supplementary Table No. 2.

Susceptibility profile of colistin-resistant carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales.

| Antimicrobials | K. pneumoniae | K. aerogenes | E. cloacae | CR-CPE | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2020 | 2022 | Total | 2016 | 2020 | 2022 | Total | 2016 | 2020 | 2022 | ||

| Tigecycline | 5/5(100%) | 46/52(88.5%) | 6/6(100%) | 57/63(90.5%) | – | 0/1(0%) | 8/8(100%) | 8/9(88.9%) | – | 1/1(100%) | – | 65/72(90.3%) |

| Amikacine | 2/5(40%) | 6/52(11.5%) | 0/6(0%) | 8/63(12.7%) | – | 0/1(0%) | 1/8(12.5%) | 1/9(11.1%) | – | 1/1(100%) | – | 10/73(1.4%) |

| Gentamicine | 2/4(50%) | 47/52(90.4%) | 4/6(66.7%) | 53/62(85.5%) | – | 0/1(0%) | 1/8(12.5%) | 1/9(11.1%) | – | 1/1(100%) | – | 55/72(76.4%) |

| Ciprofloxacine | 2/5(40%) | 0/52(0%) | 0/6(0%) | 2/63(3.17%) | – | 0/1(0%) | 1/8(12.5%) | 1/9(11.1%) | – | 0/1(0%) | – | 3/73(4.1%) |

| Sulfamethoxazole/timethoprim | NT | 2/52(3.8%) | 0/6(0%) | 2/58(3.5%) | – | 0/1(0%) | 1/8(12.5%) | 1/9(11.1%) | – | 1/1(100%) | – | 4/68(5.9%) |

| Ceftazidime/avibactam | NT | 35/35(100%) | 6/6(100%) | 41/41(100%) | – | 1/1(100%) | 8/8(100%) | 9/9(100%) | – | 1/1(100%) | – | 51/51(100%) |

| Meropenem/varbobactam | NT | 21/21(100%) | 6/6(100%) | 27/27(100%) | – | 1/1(100%) | 8/8(100%) | 9/9(100%) | – | 1/1(100%) | – | 37/37(100%) |

Number of susceptible isolates/numbers of total isolates tested (percentage).

–: no isolates during the period.

CR-CPE: colistin-resistant carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales.

NT: not tested.

Fifty-one (85%) of the colistin-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates exhibited an XDR phenotype (60 isolates tested), while 87.5% of the colistin-resistant K. aerogenes isolates also exhibited an XDR phenotype.

Colistin resistance in Enterobacterales has been found to be on the rise worldwide. The global frequency was 1.6% in 2013, rising to 3.6% in 2019. Based on these data, Latin America had the highest prevalence rates (6.7%)1. Our results demonstrated a similar pattern across the three time periods studied, describing an increased rate (3.73–23.73%) among the isolates analyzed.

Our study focused on CPE and detected a global prevalence of colistin resistance of 21.9%. Similar high CR values in CPE have been reported in other countries such as Greece, Spain, and Italy, mainly in carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae, with values ranging from 40.4% (2019) to 31% and 43% (2013) respectively. According to various authors, high rates of colistin resistance are associated with outbreaks8. Despite scarce data on CR-CPE in Latin America, Brazil reported high values (35.5%), owing primarily to KPC-2 outbreaks13. In Ecuador, another study demonstrated a clonal CPE dissemination, a situation that could explain the high CR-CPE rate found in this study15.

A national plan to tackle antimicrobial resistance was launched in 2019 in Ecuador, involving the establishment of infection control committees in each hospital unit as well as the implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship program. However, until the publication of this report, there are no official data providing antibiotic resistance patterns in our country or healthcare-associated infections. In Ecuador, as in other Latin American countries, there is a scarcity of data on antimicrobial consumption in the community and inside the hospitals and, additionally, the administration of antibiotics without a medical prescription is a common practice, which highlights the lack of regulatory measures, thus contributing to antimicrobial resistance7.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that the World Health Organization (WHO) considers antibiotic consumption in livestock a critical factor in the fight against antimicrobial resistance in the One Health Approach. Colistin use in animals was forbidden in Ecuador only in 2019, although there is limited information regarding the adherence to this regulation.

The mcr-1 gene is globally the most clinically and epidemiologically significant variant of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance, as its phenotypic expression is colistin resistance. Surprisingly, no isolates harboring the mcr-1 gene were detected in our research. The mcr-1 gene has previously been reported in a clinical E. coli isolate collected in Ecuador in 2016, although the few reports available are limited to animal samples and environmental sources. To the best of our knowledge, only mcr-1, mcr-3 and mcr-5 variants have been identified in Latin America. The mcr-3 gene was identified in Brazil (E. coli isolated from pig samples) and mcr-5 was reported in Colombia in an E. coli isolate obtained from a human urinary sample4. Therefore, we could assume that the colistin resistance in our isolates is due to chromosomal mutations rather than to plasmid-mediated mcr mechanisms, which is consistent with the epidemiologic data documented in the region. Additionally, our collection was predominantly made up of K. pneumoniae (89.2%), and although the MCR-1 enzyme is mainly described in E. coli11, we believe that further studies are required to confirm these mutations or explore other resistance mechanisms that may be involved.

All CR-CPE isolates harbored the blaKPC gene. Several authors have described KPC as the major carbapenemase type involved in high colistin-resistant rates in CPE8,12. Additionally, our results showed K. aerogenes as the microorganism with the highest colistin resistance rate, as described by other authors3. This phenomenon was observed in one hospital unit, which could be attributable to an outbreak; unfortunately, clonality studies were not available.

An increasing resistance trend in CR-K. pneumoniae to amikacin, ciprofloxacin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was observed during the three time periods of the study. In our study, most of our isolates showed co-resistance to aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones. It is a frequent phenotype observed in CPE in Latin American regions such as Brazil or Argentina2,16. This is a very concerning situation since these isolates are classified as XDR, which implies that giving high priority to the discovery of new medications is crucial in research and that other antibiotics such as tigecycline, ceftazidime–avibactam or meropenem/vaborbactam should be widely available.

This study has some potential limitations. First, considering its descriptive and retrospective methodological approach, and the small number of samples studied, we could not extrapolate our findings to other cities or healthcare institutions. Second, the different periods included may not represent an endemicity in the country and the presence of outbreaks could be misrepresented. Third, we conducted our research solely on mcr-1 and were unable to investigate other colistin-resistant mechanisms. Despite these limitations, the situation illustrated shows the scarcity of strategies within the hospital units to prevent or control the spread of multidrug-resistant microorganisms, highlighting the need for quantifying the impact of antimicrobial stewardship programs and infection control strategies in each hospital included in this study.

In conclusion, colistin resistance has dramatically increased in carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales in Ecuador and is not mediated by the presence of the mcr-1 gene. Our results highlight the need for The Ministry of Health to closely monitor national politics on antimicrobial resistance under the One Health Approach.

CRediT authorship contribution statementSSCL, SSC, GFJ contributed to study conception, design, and analysis.

SSCL wrote the draft version of the manuscript. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participateThe study was carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the “Comité de Etica de Investigación en Seres Humanos de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (PUCE)” [EO-26-2021] for strains collected during 2022. “Comité de Etica del Hospital Clinica Kennedy” [HCK-CEISH-19-0016] approved the research for isolates obtained during 2020, and for the samples collected during 2016 the Comité de Bioética “Hospital Luis Vernaza (HLV-DOF-CE-008)”.

Informed consent was waived by the Ethical Committees of PUCE and Clínica Kennedy because we collected the strains from biological samples and the clinical information was anonymized. No data could be gathered from the subjects from whom the strains were isolated. We gained approval from each institution's clinical records committee. There was no risk to the subjects, and the study was found to be of high public health benefit.

Informed consent was obtained for the patients to participate in the research carried out during 2016, which was approved by the Comité de Bioética “Hospital Luis Vernaza”.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

FundingThis work was supported by Universidad Católica de Santiago de Guayaquil [grant number SIU#510-298, 2020], [grant number SINDE 0875-2015, 2015] and Sosecali C. LTDA [grant number 001-020, 2022].

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availabilityThe datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.