Microbial pigments are extensively used in industry as food coloring, dyes, and medicinal substances. This study aimed to develop a probiotic mouth freshener tablet containing PC, tarragon essential oil, and microencapsulated Lactobacillus plantarum and investigate its antimicrobial properties against Streptococcus mutans. First, cyanobacterium Spirulina sp. was cultured and PC extracted. Then, microbial suspension and microencapsulation of probiotic bacteria, tarragon essential oil extraction, as well as mouth freshener tablets were prepared. Four treatments (T) under Co: control sample, T1, T2, T3, and T4 contained 1% PC, 1% microcoating probiotic, 0.8% tarragon essential oil, and 1% PC+1% microcoating probiotic+0.8% tarragon essential oil, were prepared respectively. The results of the inhibition zone diameter of samples also indicated that the highest and lowest sensitivity were observed in T4 and T1, respectively. Based on the results, the addition of PC and tarragon essential oil significantly increased the antioxidant activity of the samples (p<0.05). The results indicated that the release rate of probiotic bacteria under gastric conditions in T4 was lower compared to that in treatment T2 (p<0.05). Sensory evaluation results showed that the highest values were observed in T3 and T4 (p<0.05).

ConclusionOverall, it can be concluded that the prepared mouth freshener tablets (T4) can be effective agents for oral disinfection and the promotion of public health.

Los pigmentos microbianos se utilizan ampliamente en la industria como colorantes alimentarios, tintes y sustancias medicinales. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo desarrollar una tableta probiótica refrescante bucal que contiene PC, aceite esencial de estragón y Lactobacillus plantarum microencapsulado e investigar sus propiedades antimicrobianas contra Streptococcus mutans. Primero, se cultivó la cianobacteria Spirulina sp. y se extrajo PC. Luego, se prepararon la suspensión microbiana y la microencapsulación de bacterias probióticas, la extracción de aceite esencial de estragón y las tabletas refrescantes bucales. Se prepararon cuatro tratamientos (T) bajo Co: muestra de control, T1, T2, T3 y T4 que contenían 1% PC, 1% probiótico de microrecubrimiento, 0,8% de aceite esencial de estragón y 1% PC+1% probiótico de microrecubrimiento+0,8% de aceite esencial de estragón, respectivamente. Los resultados del diámetro de la zona de inhibición de las muestras también indicaron que la sensibilidad más alta y más baja se observaron en T4 y T1, respectivamente. Según los resultados, la adición de PC y aceite esencial de estragón aumentó significativamente la actividad antioxidante de las muestras (p<0,05). Los resultados indicaron que la tasa de liberación de bacterias probióticas en condiciones gástricas en el tratamiento T4 fue menor que en el tratamiento T2 (p<0,05). La evaluación sensorial mostró que los valores más altos se observaron en los tratamientos T3 y T4 (p<0,05).

ConclusiónEn general, se puede concluir que las tabletas de refrescante bucal preparadas (T4) pueden ser agentes eficaces para la desinfección bucal y la promoción de la salud pública.

Dental caries and periodontal disease are major oral health concerns in industrialized countries, affecting both children and adults. Streptococcus mutans, a key bacterium, causes tooth caries by metabolizing dietary carbohydrates, generating acid, and demineralizing teeth. Lowering the pH increases acid tolerance and enables S. mutans to cling to tooth surfaces through sticky glucans produced by refined sugar-derived glucosyltransferases (GTFs). Preventive dental caries methods aim to reduce tooth demineralization risk and prevent permanent damage, suggesting innovative approaches for effective caries prevention5.

Lactic acid bacteria, particularly Lactobacillus and Pediococcus strains, are crucial in probiotic formulations for treating intestinal dysfunctions. In dentistry, probiotic strains may act as antagonists against cariogenic bacteria, reducing S. mutans levels in saliva or plaque. The exact method of probiotic action in the oral cavity remains unclear. Probiotics reduce caries pathogenic colony-forming units, prevent periodontal infections, produce chemicals, and manage inflammatory responses and may indirectly enhance oral health through immune processes14.

Tarragon (Artemisia dracunculus L.), a perennial subshrub, is used as a spice. Its essential oil, derived from tarragon leaves, has antimicrobial, insecticidal, antiseptic, and anti-inflammatory properties. It is also known for its antioxidant and neuroprotective properties. The primary constituents of tarragon essential oil include estragole, limonene, methyleugenol, sabinene, and terpinen-4-ol46.

Bioactive compounds in microalgae extracts can disrupt bacterial cell membranes, enhancing permeability and leaching essential ions such as potassium, potentially leading to cellular death. This is primarily due to the incorporation of hydrophobic compounds containing bacterial cell wall phospholipids. PC is a phycobiliprotein possessing antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, and neuroprotective properties. However PC is unstable when exposed to heat and light in an aqueous solution and the protein moiety denatures at temperatures above 45°C, leading to changes in color. Instability related to protein stability and/or microbial spoilage can be improved by formulation engineering, e.g. by using additives such as trehalose, citric acid or glycerol. Nutritional PC may be non-covalently bound to gelatin (GE) and form the self-assembly complex proteins, which could stabilize high internal phase emulsions (HIPEs) by one-pot homogenization. C-PC can be a valuable natural ingredient in the formulation of nutraceutical and cosmeceutical products8. Moreover, C-PC has been evaluated in different studies for its potential antimicrobial in vitro effects. Activities against bacteria involved in acne and in dermatitis10 and against bacteria with a high level of intrinsic resistance to most antibiotics, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and others, were reported8. On the other hand, for remote sensing applications, researchers have extensively used PC, as the marker pigment for estimating the presence of cyanobacteria27. Moreover, PC has shown protective activity in animal models of diverse human health diseases, often reflecting antioxidant, anti-inflammatory effects32 and for the treatment of many diseases, such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's diseases42. Furthermore, the fluorescence properties of PC and its corresponding quenching effects are investigated in the presenceof human serum albumin (HSA)47.

As no research has demonstrated the formulation of a mouth freshener tablet utilizing PC extracted from Spirulina sp., nor assessed its antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, the main goal of this research was to formulate a probiotic mouth freshener incorporating PC, tarragon essential oil, and Lactobacillus plantarum, and to examine their antimicrobial efficacy against S. mutans.

Materials and methodsCulture conditions of Spirulina sp.The cyanobacterial species Spirulina sp. was isolated from the cyanobacteria culture collection (CCC) of the ALBORZ Herbarium at the Science and Research Branch of the Islamic Azad University in Tehran. The bacterium was cultivated in modified Zarrouk medium under illumination of 3001/m2/s1 at a temperature of 28±2°C for 30 days30.

Extraction and purification of analytical grade of phycocyaninThe study involved the extraction and purification of PC from a 14-day-old log-phase culture29,30. PC was extracted from the culture by centrifuging at 4000rpm to obtain a pellet. The pellet was then suspended in acetic acid-sodium acetate buffer and PC was extracted using repeated freezing and thawing methods until the cell biomass turned dark purple. The crude extract was obtained by centrifugation at 5000rpm for 10min. Purification was done using the Afreen and Fatma's method, adding solid ammonium sulfate to achieve 65% saturation. The solution was then centrifuged at 4500×g for 10min. The pellets were resuspended in 50mM acetic acid-sodium acetate buffer and dialyzed overnight. The extracts were then filtered through a 0.45μm filter48.

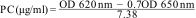

The absorbance of phycoerythrin solution was measured on a CARY 500 Scan UV-Vis spectrophotometer at wavelengths of 250–700nm for calculating the concentration of phycoerythrin, using the following equation. The purity ratio of PC was calculated from absorbance measurements at 620 and 652nm (A620/A652), as per the equations (1)27 (Fig. S1).

Preparation of the microbial suspension and microencapsulation of probiotic bacteriaThe preparation of the microbial suspension was done by culturing L. plantarum ATCC 1058 (18h) in 500ml of deMan Rogosa Sharpe (MRS) broth medium at a temperature of 37°C. Bacterial cells were collected by centrifuging at a speed of 5000rpm at a temperature of 37°C for 10min. The collected cells were washed twice with 0.9% normal saline solution under the mentioned conditions and finally diluted with normal saline solution to 100ml6.

The encapsulation of probiotic microorganisms was achieved using the external gelation method. For this purpose, 2g of sodium alginate was added to a beaker containing 100ml of distilled water. The mixture was then stirred using a magnet at a speed of 200rpm until the sodium alginate was completely dissolved in the distilled water. To allow the sodium alginate to be absorbed, the mixture was refrigerated overnight. Subsequently, the sample was removed from the refrigerator and allowed to equilibrate with the ambient temperature of the laboratory. Then, 18g of an aseptic sodium alginate solution (canola oil) and 1g of a bacterial suspension with 0.5CFU/ml were mixed.

During this stage, the rapeseed oil quantity was sterilized by passing it through a Millipore filter with a diameter of 0.22μm, ensuring its sterility for further processing. The alginate and bacterium mixture were carefully introduced into 100g of liquid rapeseed oil, which already included 1.5g of Tween 80. A magnetic stirrer was used to agitate the oil at 900rpm. The stirring process lasted 20min, ensuring that the mixture was equally dispersed. To start the gelatinization process, 40ml of an emulsion with calcium ions was added. This was made by mixing 60g of liquid rapeseed oil, 1.5g of Tween 80, and 5.62mmol of calcium chloride. The agitation procedure continued for 20min until alginate droplets were generated, and the solution was agitated for an additional 30min to complete the gelation process. The interaction between alginate and the calcium solution led to the formation of the capsule wall, causing the grains to settle as little droplets. In the end, a two-phase system was created. Subsequently, the solution was transferred to the decanter funnel, and 40ml of peptone saline buffer was introduced to facilitate phase separation. The solution was exposed to these conditions for 30min, after which the capsules were effortlessly extracted from the decanter. The aforementioned stages were executed in a totally aseptic environment. Following the production and separation of the microcapsules from the oily phase, a sonicator bath was used for 30min under sterile conditions to decrease the particle size20.

Tarragon essential oil extractionThe tarragon sample under the scientific name Artemisia tarragon L. was prepared fresh from the Medicinal Plants Research Institute. Then, its leaves were separated after washing and dried for 2 days at room temperature and finally crushed with an electric mill. For this purpose, the extraction of essential oil was carried out using a Cloninger apparatus. In this way, 100g of the dried plant was poured into a 2000ml flask and about 1000ml of distilled water was added to it, and extraction and essential oil extraction was done. The time required for extraction was considered to be about 3h. During this time, the volatile compounds were removed with water vapor and after cooling, they were visible as a distinct layer on the surface of the water in the measuring tube of the Cloninger device. To collect the essential oil, the tap of the measuring tube was opened, after removing the excess water from the tube, the essential oil was collected in a separate container and dehydrated by anhydrous sodium sulfate. In order to prevent the decomposition of the essential oil by light and heat, a dark colored glass container was used to store the essential oil43.

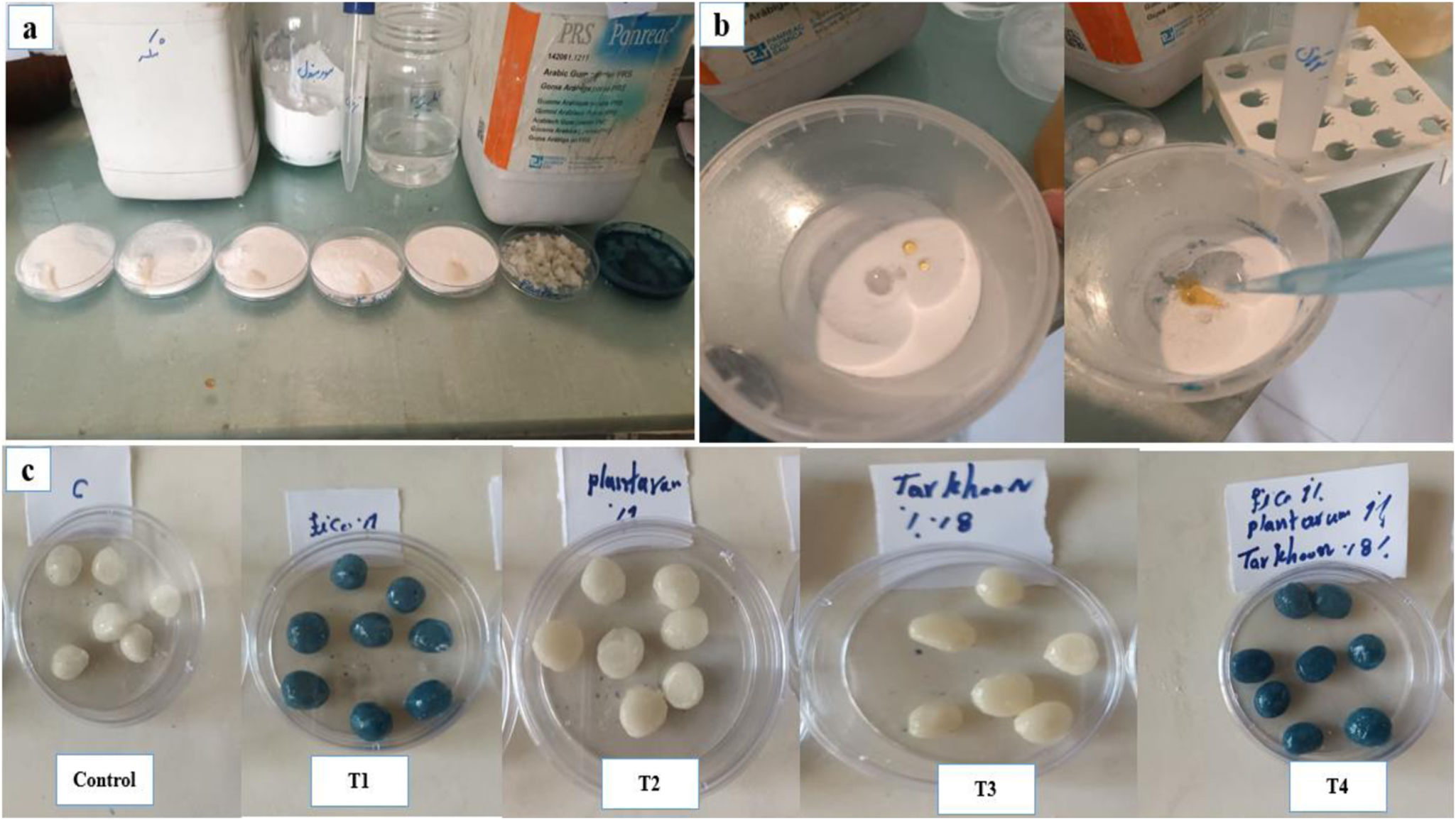

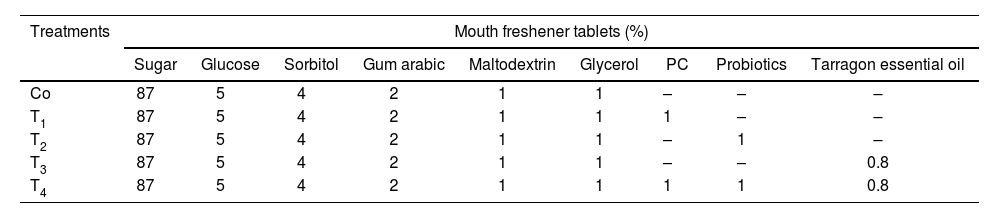

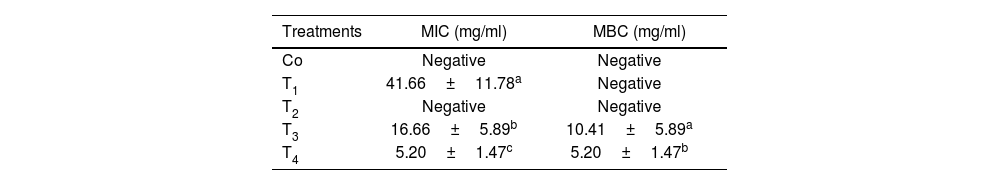

Mouth freshener tablet preparationThe basic formula of the tablets was prepared by combining dry ingredients such as sugar, gum arabic, sorbitol, and maltodextrin, with glucose and glycerol (Fig. 1). Microcoatings (1%, v/w), PC (1%, v/w), and 0.8% tarragon essential oil were added. The tablets were poured into silicone molds, refrigerated for 4h, and stored at room temperature19. The formulation of the examined samples was based on Table 1.

Mouth freshener tablet preparation. (a) Different ingredients of sugar, gum arabic, sorbitol and maltodextrin, and then glucose, glycerol, and microcapsules. (b) Mixing the ingredients. (c) Treatment of control sample, T1: 1% PC, T2: 1% microcoating probiotic, T3: 0.8% tarragon essential oil, T4: 1% PC+1% microcoating probiotic+0.8% tarragon essential oil.

Formulation of the mouth freshener tablets (%).

| Treatments | Mouth freshener tablets (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugar | Glucose | Sorbitol | Gum arabic | Maltodextrin | Glycerol | PC | Probiotics | Tarragon essential oil | |

| Co | 87 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – |

| T1 | 87 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – |

| T2 | 87 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| T3 | 87 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | – | – | 0.8 |

| T4 | 87 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.8 |

Calculation of the EY percentage was modified from that previously reported23 as follows: Eq. (1), where N0 and N represented the number of viable CFUs before and after the encapsulation process, respectively.

Microscopic analysis by SEMThe surface morphology of microcapsules was analyzed using a scanning electron microscope with an acceleration voltage of 20kV. The dry microcapsules adhered to metal stubs using double-sided tape, and then covered with gold using a gold sputter coater in a high-vacuum evaporator. This method yielded high-resolution microscopic images at the chosen level of magnification22.

Antibacterial analysisDetermination of the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC)Streptococcus mutans (PTCC 1683) was obtained from the collection center of industrial microorganisms. The MIC and MBC were determined using a standard susceptibility agar dilution technique. For this purpose, different concentrations of sample solution containing bioactive compounds (0–200ppm) were prepared. The microbial suspension of S. mutans was inoculated into 9ml of TSB and kept in a greenhouse at 37°C for 18–24h. The study involved filling tubes with antimicrobial solution to achieve a final concentration of 105CFU/ml. The MIC value was determined as the minimum concentration needed to prevent bacterial growth after 48h of incubation at 37°C. The MBC for antimicrobials was calculated using the dilution method in broth culture medium. A volume of 0.1ml was removed from the tubes showing no growth and inoculated on TSA plates. The MBC was the lowest concentration in which no colonies formed under these conditions. The detection limit for this method is 10CFU/ml, indicating a concentration below this value. Thus, MBC is the minimum antimicrobial concentration capable of inactivating over 99.99% of bacteria present1.

Inhibitory effect using the disc diffusion methodThe disc diffusion method was used to assess antimicrobial activity in bacterial strains4. Culture suspensions were calibrated against a 0.5 McFarland standard, and 100μl of the test microorganism suspension was disseminated onto solid media plates. Filter paper discs (6mm in diameter) were saturated with extracts and placed on the plates. The plates were incubated for 24 and 48h for the respective bacterial strains. Positive controls included antibiotic discs of ampicillin (Amp, 10μg/disc), gentamicin (CN, 10μg/disc), and amikacin (AK, 30μg/disc), while negative controls used paper discs impregnated with solvents. The diameters of the inhibition zones were used as indicators of antimicrobial activity.

Antioxidant activity of the mouth freshener tabletsThis study followed Rajauria et al.’s36 DPPH procedure using 96-well microtiter plates. The mixture contained 2.5ml of DPPH radical solution and different concentrations of mouth freshener (100, 150, 200, 300, 500μl). The reaction mixtures were kept in a dark environment at 30°C for 30min. Absorption measurements were conducted at a wavelength of 517nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometric plate reader (BioTek USA)36.

In vitro release rate of the mouth freshener tablets under gastric conditionsIn order to check the release rate of the mouth freshener tablets, 1g of each sample was mixed with distilled water and allowed to absorb the water for 15min. The samples that absorbed water and swelled were added to 5ml of the simulated stomach solution and the solution was placed on a shaker incubator for 2h. Afterwards, 1ml of the solution was mixed with 9ml of phosphate buffer and placed on the shaker in order to release the microencapsulation. To check the amount of damage to bacteria after dilution, samples were cultured on solid MRS medium and placed in an incubator for 24–48h13.

TextureTextural parameters, including firmness, springiness, and stickiness of the tablets, were measured with a texture measuring device. For this purpose, a Brookfield histometer with a cylindrical probe (TA25/1000) and a speed of 2mm/s was used. The length of the samples was 10mm, width 10mm and height 10mm33.

Sensorial evaluationSensory analysis utilized a 5-point scale, with scores ranging from 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest), assessed by 30 trained panelists. The quality of the mouth freshener tablets was assessed based on their sensory characteristics, including general acceptability, chewing ability, adhesion to the wrapper, adhesion to the teeth, texture, taste, and aroma35.

Statistical analysisThe experimen results were analyzed using ANOVA in SPSS version 22, with a 95% significance level. The Tukey test assessed differences in mean values after ANOVA detection. Three replicated measurements were conducted for each treatment, and mean values were determined31.

ResultsSpectroscopy, purity, and concentration of PCThe results showed that the maximum adsorption (λmax) of PC extracted from Spirulina sp. was reported at a wavelength of 620nm with an absorption of 0.372nm. The results of the concentration and purity of the extracted PC showed that the values were 0.0029±0.001 and 2.40±0.07mg/ml, respectively (Fig. S2).

Microencapsulation efficacy of probiotic bacteriaThe microencapsulation efficiency of L. plantarum probiotic bacteria with sodium alginate was 95.96±0.24%.

Morphological results of encapsulated bacteriaThe morphological results of probiotic bacteria coated with sodium alginate at various magnifications are shown in Fig. S3. The results indicated that the microcoatings exhibited particle sizes ranging from 108.59 to 161.302μm and suggest that the microcapsules showed a spherical morphology and an irregular surface characterized by pore-like fissures. A variety of coated bacteria are presented, each potentially containing one or more bacteria within its coating. The observed mass at the center is likely free of uncoated bacteria. Fig. S3(a)–(d) shows a capsule that may harbor one or more bacteria.

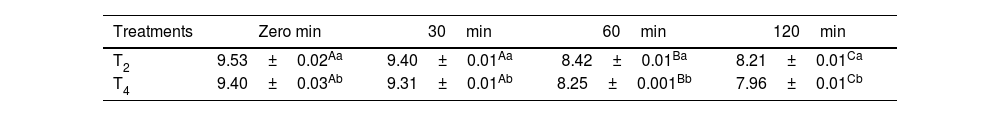

Mouth freshener tablet analysesResults of antimicrobial activity against Streptococcus mutansThe determination of the MIC for the mouth freshener tablets revealed that the control sample and T2 exhibited no inhibitory activity against S. mutans (p>0.05). In contrast, tablets containing PC and tarragon essential oil demonstrated significant MIC activity (p<0.05). The findings indicated that T4 exhibited the highest sensitivity (5.20±1.47mg/ml), while T1 demonstrated the lowest sensitivity (p<0.05).

The MBC findings showed that the control sample, T1, and T2 exhibited no lethal activity against S. mutans (p>0.05). The results indicate that T4 exhibited the greatest sensitivity, while T3 demonstrated the lowest sensitivity, with a significant difference (p<0.05) (Table 2).

Results of the average MIC and MBC (mg/ml) tests, and average inhibition zone diameter (mm) of Lactobacillus plantarum probiotic mouth freshener tables containing phycocyanin and tarragon essential oil against Streptococcus mutants.

| Treatments | MIC (mg/ml) | MBC (mg/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| Co | Negative | Negative |

| T1 | 41.66±11.78a | Negative |

| T2 | Negative | Negative |

| T3 | 16.66±5.89b | 10.41±5.89a |

| T4 | 5.20±1.47c | 5.20±1.47b |

| Treatment | Inhibition zone diameter (mm) |

|---|---|

| Co | Negative |

| T1 | 1.83±0.09a |

| T2 | Negative |

| T3 | 8.40±0.08b |

| T4 | 8.90±0.08c |

Co: control sample/T1: contains 1% phycocyanin/T2: contains 1% microcoating probiotic/T3: contains 0.8% tarragon essential oil/T4: contains 1% phycocyanin+1% microcoating probiotic+0.8% tarragon essential oil.

Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences in each column (p<0.05).

The inhibition zone diameter of the mouth freshener tablets indicated that the control sample and T2 exhibited no growth diameter against S. mutans (p>0.05). In contrast, the inhibition zone diameter of tablets containing PC and tarragon essential oil was significant (p<0.05). The findings showed that the highest and lowest value corresponded to T4 and T1, respectively (p<0.05) (Table 3) (Figs. S4 and S5).

Results of the in vitro release rate of Lactobacillus plantarum probiotic mouth freshener tablets containing phycocyanin and tarragon essential oil during 120min under stomach conditions.

| Treatments | Zero min | 30min | 60min | 120min |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2 | 9.53±0.02Aa | 9.40±0.01Aa | 8.42±0.01Ba | 8.21±0.01Ca |

| T4 | 9.40±0.03Ab | 9.31±0.01Ab | 8.25±0.001Bb | 7.96±0.01Cb |

T2: contains 1% microcoating probiotic/T4: contains 1% phycocyanin+1% microcoating probiotic+0.8% tarragon essential oil.

Different small and capital letters indicate a significant difference in the column and row respectively (p<0.05).

The results showed that varying treatments and durations significantly influenced the antioxidant activity of the mouth freshener tablets (p<0.05). The results indicate that the incorporation of PC and tarragon essential oil markedly enhanced the antioxidant activity of the samples (p<0.05). T4 exhibited the highest activity, while the control and T2 treatments showed the lowest values (p<0.05). During a 60-day storage period, a notable reduction in antioxidant activity was observed across all examined groups (p<0.05) (Table S1).

In vitro release rate of the mouth freshener tablets under gastric conditionsThe release rate of probiotic bacteria in treatments T2 and T4 was significant and affected by the tablet formulation (p<0.05). A significant difference was observed in all measured minutes between the two treatments, T2 and T4, with the T4 treatment exhibiting a lower release rate of prebiotic bacteria compared to the T2 treatment (p<0.05). During 120min simulated stomach conditions, the release of probiotic bacteria increased significantly (p<0.05). This increase persisted in the T4-treated tablets, albeit at a slower rate (Table 3).

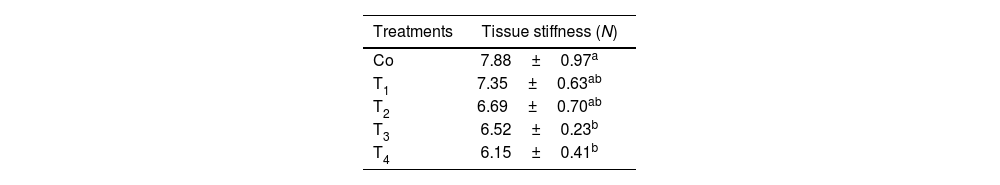

Texture resultsStiffnessThe results of texture stiffness of the mouth freshener tablets with different formulations are shown in Table 4. Based on the results of the different treatments, they had a significant effect on the stiffness of the mouth freshener tablets (p<0.05). In the light of these results, the addition of PC, microencapsulated probiotics and tarragon essential oil significantly reduced the hardness of the tablet samples (p<0.05). The lowest value corresponded to the T3 and T4 samples (p<0.05), while the control sample reported the highest stiffness (p<0.05).

Results of the average tissue stiffness (N), tissue coherence and cohesion of the texture (mm) and tissue springiness (mm) of Lactobacillus plantarum probiotic mouth freshener tablets containing phycocyanin and tarragon essential oil.

| Treatments | Tissue stiffness (N) |

|---|---|

| Co | 7.88±0.97a |

| T1 | 7.35±0.63ab |

| T2 | 6.69±0.70ab |

| T3 | 6.52±0.23b |

| T4 | 6.15±0.41b |

| Treatments | Coherence and cohesion (mm) |

|---|---|

| Co | 0.31±0.03d |

| T1 | 0.46±0.01c |

| T2 | 0.41±0.07b |

| T3 | 0.40±0.04b |

| T4 | 0.49±0.03a |

| Treatments | Springiness (mm) |

|---|---|

| Co | 1.10±0.10a |

| T1 | 1.16±0.05a |

| T2 | 1.16±0.15a |

| T3 | 1.20±0.09a |

| T4 | 1.28±0.02a |

Co: control sample/T1: contains 1% phycocyanin/T2: contains 1% microcoating probiotic/T3: contains 0.8% tarragon essential oil/T4: contains 1% phycocyanin+1% microcoating probiotic+0.8% tarragon essential oil.

Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences in each column (p<0.05).

The results of the coherence and cohesion of the mouth freshener tablets with different formulations are shown in Table 4. Based on these results, different treatments had a significant effect on the coherence and cohesion of the texture of the tablets (p<0.05). Moreover, the addition of PC, microencapsulated probiotics, and tarragon essential oil significantly increased the cohesion and cohesion of the tablet samples (p<0.05). The lowest amount of tissue cohesion was observed in the control sample (p<0.05). The highest amount of tissue cohesion was reported in the T4 sample (p<0.05).

SpringinessThe results of the springiness of the mouth freshener tablets with different formulations are shown in Table 4. The results of the various treatments indicated no significant effect on the springiness of the mouth freshener tablets (p>0.05) (Table 4).

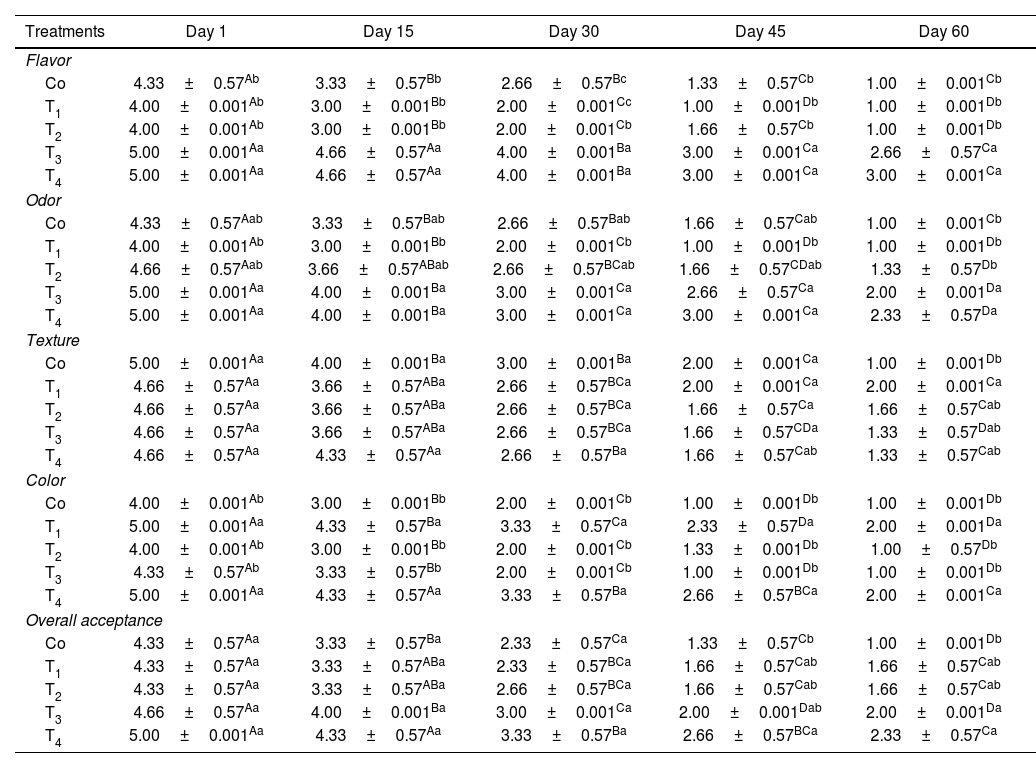

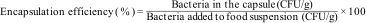

Sensory evaluation resultsFlavorThe findings indicated that the various treatments and durations significantly influenced the sensory evaluation of the flavor of the mouth freshener tablets (p<0.05). Based on these results, the incorporation of tarragon essential oil markedly enhanced the sensory evaluation of the flavor of the tablet samples (p<0.05). The concurrent application of 0.8% tarragon essential oil and 1% PC (T4 treatment) markedly enhanced the flavor score of the samples (p<0.05). The lowest amount belonged to the control, T1 and T2, whereas the T3 and T4 samples showed the highest amount (p<0.05). During a 60-day storage period, a notable decline in the sensory evaluation of flavor was observed across all the investigated groups (p<0.05) (Table 5).

Results of the average sensory evaluation of Lactobacillus plantarum probiotic mouth freshener tablets containing phycocyanin and tarragon essential oil during 60 days.

| Treatments | Day 1 | Day 15 | Day 30 | Day 45 | Day 60 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavor | |||||

| Co | 4.33±0.57Ab | 3.33±0.57Bb | 2.66±0.57Bc | 1.33±0.57Cb | 1.00±0.001Cb |

| T1 | 4.00±0.001Ab | 3.00±0.001Bb | 2.00±0.001Cc | 1.00±0.001Db | 1.00±0.001Db |

| T2 | 4.00±0.001Ab | 3.00±0.001Bb | 2.00±0.001Cb | 1.66±0.57Cb | 1.00±0.001Db |

| T3 | 5.00±0.001Aa | 4.66±0.57Aa | 4.00±0.001Ba | 3.00±0.001Ca | 2.66±0.57Ca |

| T4 | 5.00±0.001Aa | 4.66±0.57Aa | 4.00±0.001Ba | 3.00±0.001Ca | 3.00±0.001Ca |

| Odor | |||||

| Co | 4.33±0.57Aab | 3.33±0.57Bab | 2.66±0.57Bab | 1.66±0.57Cab | 1.00±0.001Cb |

| T1 | 4.00±0.001Ab | 3.00±0.001Bb | 2.00±0.001Cb | 1.00±0.001Db | 1.00±0.001Db |

| T2 | 4.66±0.57Aab | 3.66±0.57ABab | 2.66±0.57BCab | 1.66±0.57CDab | 1.33±0.57Db |

| T3 | 5.00±0.001Aa | 4.00±0.001Ba | 3.00±0.001Ca | 2.66±0.57Ca | 2.00±0.001Da |

| T4 | 5.00±0.001Aa | 4.00±0.001Ba | 3.00±0.001Ca | 3.00±0.001Ca | 2.33±0.57Da |

| Texture | |||||

| Co | 5.00±0.001Aa | 4.00±0.001Ba | 3.00±0.001Ba | 2.00±0.001Ca | 1.00±0.001Db |

| T1 | 4.66±0.57Aa | 3.66±0.57ABa | 2.66±0.57BCa | 2.00±0.001Ca | 2.00±0.001Ca |

| T2 | 4.66±0.57Aa | 3.66±0.57ABa | 2.66±0.57BCa | 1.66±0.57Ca | 1.66±0.57Cab |

| T3 | 4.66±0.57Aa | 3.66±0.57ABa | 2.66±0.57BCa | 1.66±0.57CDa | 1.33±0.57Dab |

| T4 | 4.66±0.57Aa | 4.33±0.57Aa | 2.66±0.57Ba | 1.66±0.57Cab | 1.33±0.57Cab |

| Color | |||||

| Co | 4.00±0.001Ab | 3.00±0.001Bb | 2.00±0.001Cb | 1.00±0.001Db | 1.00±0.001Db |

| T1 | 5.00±0.001Aa | 4.33±0.57Ba | 3.33±0.57Ca | 2.33±0.57Da | 2.00±0.001Da |

| T2 | 4.00±0.001Ab | 3.00±0.001Bb | 2.00±0.001Cb | 1.33±0.001Db | 1.00±0.57Db |

| T3 | 4.33±0.57Ab | 3.33±0.57Bb | 2.00±0.001Cb | 1.00±0.001Db | 1.00±0.001Db |

| T4 | 5.00±0.001Aa | 4.33±0.57Aa | 3.33±0.57Ba | 2.66±0.57BCa | 2.00±0.001Ca |

| Overall acceptance | |||||

| Co | 4.33±0.57Aa | 3.33±0.57Ba | 2.33±0.57Ca | 1.33±0.57Cb | 1.00±0.001Db |

| T1 | 4.33±0.57Aa | 3.33±0.57ABa | 2.33±0.57BCa | 1.66±0.57Cab | 1.66±0.57Cab |

| T2 | 4.33±0.57Aa | 3.33±0.57ABa | 2.66±0.57BCa | 1.66±0.57Cab | 1.66±0.57Cab |

| T3 | 4.66±0.57Aa | 4.00±0.001Ba | 3.00±0.001Ca | 2.00±0.001Dab | 2.00±0.001Da |

| T4 | 5.00±0.001Aa | 4.33±0.57Aa | 3.33±0.57Ba | 2.66±0.57BCa | 2.33±0.57Ca |

Co: control sample/T1: contains 1% phycocyanin/T2: contains 1% microcoating probiotic/T3: contains 0.8% tarragon essential oil/T4: contains 1% phycocyanin+1% microcoating probiotic+0.8% tarragon essential oil.

Different small and capital letters indicate a significant difference in the column and row respectively (p<0.05).

The findings indicated that the various treatments and durations significantly influenced the sensory evaluation of the odor of the mouth freshener tablets (p<0.05). Based on the results, the incorporation of tarragon essential oil markedly enhanced the sensory evaluation of the odor of tablet samples (p<0.05). The concurrent application of 0.8% tarragon essential oil and 1% PC (T4 treatment) markedly enhanced the odor score of the samples (p<0.05). The control samples exhibited the lowest amount, whereas the T3 and T4 samples showed the highest amount (p<0.05). During a 60-day storage period, a notable decline in sensory evaluation of odor was observed across all investigated groups (p<0.05) (Table 5).

TextureThe findings showed that the various treatments and durations significantly influenced the sensory evaluation of the texture of the mouth freshener tablets (p<0.05). The findings indicated that the incorporation of tarragon essential oil markedly enhanced the sensory evaluation score of the tablet samples (p<0.05). Moreover, within the initial 15 days, no statistically significant differences were observed among the various treatments regarding tissue evaluation (p>0.05). On the sixtieth day of the experiment, a statistically significant difference between the treatments was observed (p<0.05). The treatment with 1% PC exhibited the highest score in tissue sensory evaluation, whereas the control sample showed the lowest score (p<0.05) (Table 5).

ColorThe findings showed that the various treatments and durations significantly influenced the sensory evaluation of the color of the mouth freshener tablets (p<0.05). Based on these results, the incorporation of PC extract markedly enhanced the sensory assessment of the color of the tablet samples (p<0.05). A reduction in color sensory evaluation was observed across all the studied groups over a 60-day storage period (p<0.05). The T1 and T4 treatments exhibited the highest color sensory evaluation scores throughout the study period (p<0.05) (Table 5).

Overall acceptabilityThe findings showed that the various treatments and durations significantly influenced the sensory evaluation of the overall acceptability of the mouth freshener tablets (p<0.05). Based on these results, the addition of tarragon essential oil significantly increased the sensory evaluation of the taste of the mouth freshener tablet samples (p<0.05). The results showed that during 30 days of storage, there was no statistically significant difference among the different treatment samples (p>0.05), while on the 45th day of the experiment, a statistically significant difference in the treatments was reported (p<0.05). The control treatment showed the lowest amount of sensory assessment of overall acceptance (p<0.05) and the highest amount was observed in the T3 and T4 treatments (p<0.05) (Table 5).

DiscussionTooth decay is the most common disease, affecting 80–90% of the global population. S. mutans, a facultative anaerobic Gram-positive bacterium, is the primary etiological agent due to its carbohydrate metabolism, leading to acid production and demineralization of enamel, resulting in mineral loss and cavities. Natural products may serve as a viable option for accessing mechanisms that prevent caries and periodontal disease28.

Recent studies have examined the efficacy of oral probiotics in the reduction and prevention of oral diseases. Oral probiotics may be administered to the oral cavity to sustain microbiome equilibrium. Consequently, they are crucial for the effective delivery and release of a significant quantity of oral probiotics into the oral cavity, as these probiotics generate various antimicrobial compounds that target caries-causing microorganisms. Hence, the purpose of this research was to investigate the antimicrobial activity of tarragon extract, the probiotic bacterium L. plantarum, and PC obtained from Spirulina sp., both separately and simultaneously, focusing on their synergistic effect on S. mutans in oral deodorizing tablets.

The average microencapsulation efficiency of the probiotic bacterium L. plantarum with sodium alginate was reported to be 95.96±0.24%. The efficiency of microencapsulation is affected by the matrix wall material, the cell load in the emulsion, the selected microencapsulation technique, the size of the capsules, and the curing duration in calcium chloride11. Mahmoud et al. demonstrated that the encapsulation efficiency of L. plantarum capsules utilizing sodium alginate ranged from 98.11% to 94.94%24. Saniani et al. reported that microencapsulated L. plantarum utilizing sodium alginate, inulin, and dextran to enhance the viability of probiotic cells, achieved optimal microencapsulation efficiency (93.55) at a concentration of 1.5% inulin and 0.5% dextran44. Ali et al. demonstrated that the microencapsulation of Lactobacillus rhamnosus using alginate combined with xanthan gum (0.5%, w/v) achieved a superior microencapsulation efficiency of 95.2%, in contrast to the 85.86% efficiency observed with alginate alone2.

The study found that microcoatings with particle sizes ranging from 108.59 to 161.302μm had a spherical shape and uneven surface. The microcapsules contained a significant amount of L. plantarum, with irregular surface areas indicating higher polymer concentration. The outer surfaces of the microcapsules had walls without cracks or disturbances, providing protection against gas permeability. This continuous surface and compact structure create a stronger physical barrier against acid and bile release during digestion, preventing probiotic bacterial cells from escaping the enclosed matrix21,38.

Oral diseases are a global health concern, with S. mutans being the primary pathogen linked to dental caries and infections. Resistance of microbes to the majority of antibiotics typically employed for oral infections (including penicillin, cephalosporins, erythromycin, tetracycline and its derivatives, and metronidazole) has been recorded. The resistance of microorganisms to conventional antibiotics necessitates an immediate focus on the development of novel drug compounds. Since ancient times, it has been extensively recorded that bioactive compounds derived from cyanobacteria have been utilized as remedies for various ailments and microbial infections17. The MIC results of the mouth freshener tablets indicated that T4 exhibited the highest sensitivity and T1 had the lowest sensitivity against S. mutans. The MBC results indicated that T4 exhibited the highest sensitivity, while T3 demonstrated the lowest sensitivity. The inhibition zone diameter results indicated that S. mutans exhibited the greatest sensitivity to T4 (8.90mm) and the least sensitivity to T1 (1.83mm). The findings showed that the phenolic compounds in both tarragon extract and microalgae extract aligned closely with expectations.

Following this study, Sadeghi-Nejad et al. developed toothpaste containing dracunculus leaf extract, Satureja khuzestanica (Jamzad), and Myrtus communis (Linn), demonstrating a significant inhibitory effect on five microorganisms: S. mutans, Lactobacillus casei, Streptococcus sanguis, Streptococcus salivarius, and Candida albicans41. Arabestani et al. examined the antibacterial properties of four tarragon extracts (derived from n-hexane, ethyl acetate, methanol, and water) against two decay-causing bacteria, S. mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus3. The results indicated that the extracts exhibited significant antibacterial activity. Jafari et al. found the antimicrobial properties of Chlorella vulgaris extract against S. mutans, possibly due to flavonoids, tannins, terpenoids, and PUFAs in C. vulgaris and Dunaliella salina extracts16.

The study found that combining 0.8% tarragon essential oil and 1% PC in mouth freshener tablet formulations significantly improved antioxidant activity, attributed to the phenolic compounds of tarragon extract and the antioxidant properties of PC's chromophorbilins. The control sample showed the lowest antioxidant activity, possibly due to the alginate coating in the probiotic L. plantarum microcapsule42. These results corroborate the findings observed by Chen et al.7 and Rathnasamy et al.39, who reported an increase in antioxidant activity against other radicals with increased phycobiliprotein purity. On the other hand, the opposite trend was observed in the study by Fekrat et al.12, where the crude C-PC extract exhibited the highest antioxidant activity. Moreover, Pradhana et al.34 developed a herbal toothpaste utilizing Cestrum nocturnum essential oil, demonstrating an antioxidant efficiency with an IC50 value of 15.8μg/ml, in contrast to our studies. The authors suggest that the incorporation of natural compounds into toothpaste may serve as a competitive product for commercialization aimed at preventing gingivitis34. With regard to the mechanisms involved in antioxidant activity, PC was reported to increase the expression of antioxidant enzymes and of the well-known antioxidant glutathione. In addition, experiments carried out both in vivo with rodents fed 100mg of PC and in vitro on various cell culture models showed that PC is a potent inhibitor of NADPH oxidase, a producer of ROS8.

The simulated digestion test is a method used to study the behavior of food and pharmaceutical products in the digestive system. It offers speed, and cost-effectiveness, and avoids ethical limitations. The pH value and ionic strength of the environment affect component solubility, oil–water interface distribution, and nanoemulsion stability. In vitro studies showed consistent release rates of probiotic bacteria in mouth freshener tablets, regardless of tablet formulation. During 120min of simulated stomach conditions, the release of probiotic bacteria increased. This method circumvents ethical limitations and offers speed and cost-effectiveness. The transit through the stomach results in a reduction of both the number of viable cells and the survival rate of probiotic microorganisms, attributable to the extreme pH of gastric acid, which constrains the probiotic efficacy of these microorganisms within the digestive tract9. Numerous studies have investigated the formulation of a wall coating aimed at enhancing the survival of probiotics within the digestive tract. Findings indicate that sodium alginate combined with polysaccharides demonstrates optimal efficacy in preserving probiotic viability49. Kanmani et al.18 demonstrated that alginate/chitosan coating effectively maintained the viability of probiotic bacteria under digestive conditions, aligning with our findings. The researchers reported that probiotic cells were continuously released from microcapsules under intestinal conditions with a pH of 7.5. This may result from partially broken sodium alginate bonds during capsule preparation, leading to instability of the capsules at elevated pH levels. The findings indicate that alginate/chitosan microcapsules exhibit greater stability under gastric conditions and disintegrate in intestinal environments18.

The findings regarding the springiness of the mouth freshener tablets with varying formulations indicated that the different treatments did not significantly influence the springiness of the tablets. The analysis of the results regarding the firmness and consistency of tablets with various formulations indicated that the incorporation of PC, microcoated probiotics, and tarragon essential oil significantly diminished the firmness and consistency of the tablet samples. The T4 sample exhibited the lowest values, while the control sample showed the highest values. The study shows that adding microcapsules to the tablet matrix reduces crystal lattices and particle–particle interactions, leading to more open structures and increased voids among crystals. This is likely due to increased moisture content in the matrix, which facilitates wetting and opens the moisture phase. The addition of lecithin decreases tablet hardness, while inulin increases it. Moisture occupies the interstitial spaces between solid particles in chewable tablets, thereby decreasing chewing resistance, with a pronounced impact on smaller particle sizes45. Conversely, PC enhances food texture owing to its hydrophilic properties. Sugar alcohols, including maltodextrin, exhibit water retention in their structure attributed to the presence of hydroxyl groups. Furthermore, the numerous hydroxyl groups in the structure of gums, such as gum arabic, enhance water absorption by forming hydrogen bonds with water molecules40. Matulytė et al. demonstrated that the incorporation of Myristica fragrans into chewable tablets results in an approximately fourfold increase in tablet hardness and a 1.65-fold decrease in springiness after 28 days26. Rani et al.37 investigated the effects of varying concentrations of sodium alginate and pectin, along with the active ingredient from Moringa oleifera leaf ethanol extract (M. oleifera L.), on the physicochemical properties of chewable tablets. The study demonstrated that the swelling ratio, dissolution time, gumminess, and chewiness increased with higher concentrations of sodium alginate and pectin15.

The sensory characteristics of products, such as flavor, texture, and appearance, significantly influence consumer acceptance. Flavor is the primary determinant in food selection, followed by health-related factors. Consumers are less interested in functional foods with unpleasant flavors, despite potential health benefits. The impact of these factors on product sensory profiles should be assessed alongside viability studies after adding probiotic strains and chemical ingredients. The release of aroma and flavor compounds from mouth freshener products is a complex factor in sensory perception, with high levels of fat and volatile oils diminishing hydrophobic aromatic substances. The sensory evaluation of flavor, odor, and accessibility in the mouth freshener tablets revealed that using 0.8% tarragon essential oil and 1% PC (T4 treatment) significantly increased these aspects. The highest and lowest values were found in T4 and control, respectively, due to the presence of essential oils, terpenes, terpenoids, and aromatic compounds25.

Customer acceptance of liquid products depends on consistency and texture. A uniform appearance, absence of clotted particles, and adequate stretchability are crucial. The texture should be non-rubbery, with fizziness without curdling, and the surface should exhibit uniform color, depending on the ingredients and proportion. The analysis of texture and color in the mouth freshener tablets indicated that T1 exhibited the highest values for both parameters, whereas T4 and the control samples demonstrated the lowest values for texture and color, respectively. In comparison to our results, Rani et al. showed that the production of chewable tablets containing M. oleifera with 10% gelatin and 1.5% pectin is acceptable among consumers and this product has a better texture than other formulas37.

ConclusionPhycocyanin displays significant pharmacological activity, characterized by the chemical formula C33H38N4O6 and a molecular weight of approximately 112kDa. Phycocyanin is a natural marine pigment derived from Spirulina, a blue-green algae, characterized by its intense blue color. Recent studies have identified various biological properties of phycocyanin, including its antioxidant effects, enhancement of anti-cancer immunity, and anti-inflammatory capabilities. The quantity and nature of tetrapyrrole prosthetic groups, along with the open chain of phycocyanobilin and environmental conditions, can alter the spectroscopic properties of phycocyanin. Moreover, phycocyanin, an antioxidant, has been found to effectively eliminate the free radicals associated with oxidative damage to cellular systems. Its antioxidant activity is attributed to its ability to enhance the expression of antioxidant enzymes and glutathione, inhibit NADPH oxidase, and activate heme oxygenase-1 (Hmox1), leading to the production of antioxidant bilirubin. This study assessed the antimicrobial efficacy of tarragon extract, the probiotic bacterium L. plantarum, and PC derived from Spirulina sp., both individually and in combination, on S. mutans in oral deodorizing tablets. The overall results showed that T4, containing 1% PC+1% microcoated probiotic+0.8% tarragon essence, was the optimal treatment, enhancing the physical, antioxidant, and sensory properties of the mouth freshener tablets.

Ethical approvalNone declared.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest related to this research.