Edited by:

Rafael Vignoli - Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Argentina

José Di Conza - Instituto de Investigaciones en Bacteriología y Virología Molecular (IBaViM), Argentina

Last update: February 2025

More infoThe emergence and spread of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli carrying mcr-1 is recognized as a threat to public health. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of the mcr-1 gene in colistin-resistant E. coli isolates from commercial pig farms in Chaco, Argentina from 2020 to 2021. A total of 140 rectal swab samples were collected from pigs in six different pig production farms. Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined by broth microdilution. mcr-1 to mcr-5 genes were identified by multiplex PCR and clonality was assessed by ERIC and REP-PCR. The prevalence of mcr-1 was 16.4% and mcr-2, mcr-3, mcr-4 and mcr-5 genes were not detected. Colistin MIC values showed a bimodal distribution with a MIC50, MIC90 and a range of 4, 8 and 4–8μg/ml, respectively. The resistance profile to other antimicrobials was: ampicillin, 87% (20); ampicillin–sulbactam, 47.8% (11); amoxicillin–clavulanic, 13% (3); chloramphenicol, 82.6% (19); ciprofloxacin, 60.9% (14); minocycline, 26.1% (5) and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, 43.5% (10). Eighty-seven percent (87%) of the strains were categorized as MDR and 12 phenotypic resistance patterns with different clonality profiles were observed. A high prevalence of mcr-1 is demonstrated in colistin-free pig farms from Chaco, Argentina. The mcr-1 positive E. coli isolates showed an alarming level of multidrug resistance and high clonal diversity. It is necessary to continuously monitor the presence of the mcr-1 gene not only in pig production, but also in humans and the environment.

La aparición y propagación de Escherichia coli resistente a múltiples fármacos, portadora de mcr-1, se reconoce como una amenaza para la salud pública. El objetivo de este estudio fue determinar la prevalencia del gen mcr-1 en aislamientos de E. coli resistentes a colistina en granjas porcinas de Chaco, Argentina. Se recolectaron 140 muestras de hisopados rectales de cerdos en seis granjas de producción entre marzo de 2020 y julio de 2021. La sensibilidad antimicrobiana se evaluó mediante el método de microdilución en caldo. Los genes mcr-1, mcr-2, mcr-3, mcr-4 y mcr-5 se identificaron por PCR multiplex; la clonalidad se evaluó mediante ERIC y REP-PCR. La prevalencia de mcr-1 fue del 16,4% y no se detectaron los genes mcr-2, mcr-3, mcr-4 y mcr-5. Los valores de CIM de colistina presentaron una distribución bimodal, con unas CIM50 y CIM90 de 4 y 8μg/ml, respectivamente, y un rango de 4-8μg/ml. El perfil de resistencia a otros antimicrobianos dentro de los aislamientos mcr-1 positivos fue el siguiente: ampicilina, 87% (20); ampicilina-sulbactam, 47,8% (11); amoxicilina-clavulánico, 13% (3); cloranfenicol, 82,6% (19); ciprofloxacina, 60,9% (14); minociclina, 26,1% (5) y trimetoprima/sulfametoxazol, 43,5% (10). El 87% de las cepas se categorizaron como multidrogorresistentes (MDR) y se observaron 12 patrones fenotípicos de resistencia con diferentes perfiles de clonalidad. Se corroboró una elevada prevalencia de mcr-1 en granjas porcinas de Chaco libres de colistina. Los aislamientos de E. coli positivos para mcr-1 mostraron un nivel alarmante de multirresistencia y una alta diversidad clonal. Es necesario monitorear continuamente la presencia del gen mcr-1, no solo en la producción porcina, sino también en humanos y en el ambiente.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is recognized as a global threat to human, animal and environmental health. One of the main causes of AMR is the overuse of antimicrobials in both humans and animals. This practice selects for multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria that can be transmitted from animals to humans and vice versa. Transmission occurs through direct contact between animals and humans or through the food chain and the environment33. The emergence of MDR gram negative bacterial infections in humans has been the cause of the resurgence of colistin as a last-line antibiotic therapy25.

Colistin is a polycationic polypeptide belonging to the polymyxin family. It has been widely used in veterinary medicine for prophylaxis, metaphylaxis and treatment of enteric diarrhea in pigs2. It has also been used extensively as an animal growth promoter (AGP) in food-producing animals. In this way, animals achieve increased weight gain, improved growth performance and good feed efficiency1.

Until 2015, colistin resistance was only associated with mutations and regulatory changes mediated by chromosomal genes21,30. More recently, the first plasmid-associated colistin resistance gene (mcr-1) was reported in food, humans and pigs from China18. Soon after this finding, the presence of the mcr-1 gene and other variants (mcr-2 to mcr-10) were described worldwide13. This gene encodes an enzyme from the phosphoethanolamine (pEtN) transferase group, which introduces a pEtN group into lipid A. As a result, there is an increase in the positive charge of lipopolysaccharide and a decrease in the binding of polymyxins29.

Recently, worldwide reports have been published on the detection and characterization of the mcr-1 gene in Escherichia coli strains12. It has been reported mainly in animal and environmental samples and, to a lesser extent, in human clinical samples15. In Argentina, mcr-1-mediated colistin resistance was first documented in human infections caused by E. coli in 201624. Since then, the mcr-1 gene has been found in a variety of sources, including gulls17, poultry6, pigs4 and companion animals27.

The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of the mcr-1 gene in colistin-resistant E. coli isolates collected from intensive pig farms in Chaco, Argentina. In addition, we sought to characterize the susceptibility profiles of these isolates to different antimicrobial agents and to assess the clonal diversity among strains harboring the mcr-1 gene.

Materials and methodsStudy design and sample collectionA prospective, observational and cross-sectional study was conducted. A total of 140 rectal swabs were collected from pigs in six different farms (A, B, C, D, E and F). Sampling was carried out from March 2020 to July 2021 in different geographical areas of the province of Chaco, Argentina. For each farm, asymptomatic pigs were randomly selected on the basis of their age and production stage. Therefore, 35 weaned piglets (4–8 weeks old), 35 growing pigs (10–18 weeks old) and 70 fattening pigs (20–26 weeks old) were studied. All samples were immediately transported at 4°C to the laboratory for microbiological examination and processed within 4h. An epidemiological survey was conducted in each of the pig farms studied.

Isolation of colistin-resistant E. coliRectal swab samples were incubated overnight at 37°C in 10ml buffered peptone water (pH ≥7.2±0.2, Britania, Argentina). Subsequently, 50μl of each enrichment broth was inoculated on colistin-supplemented (3μg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, US) Mac Conkey agar (Britania, Argentina). Plates were incubated at 37±1°C for 22±2h. Colistin-resistant E. coli isolates were selected by colony morphology and identified by biochemical methods3.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testingSusceptibility to colistin was evaluated based on growth or no growth on Mueller-Hinton agar plates containing 3μg/ml colistin (COLTEST, Britania, Argentina). The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined by the broth microdilution method (Sensititre, Thermo Fisher, USA) according to CLSI5 and EUCAST7 guidelines. The antibiotics tested were ampicillin (8–16μg/ml), ampicillin/sulbactam (8/4 to 16/8μg/ml), amoxicillin/clavulanic (8/4 to 16/8μg/ml), cefuroxime (4–16μg/ml), cefotaxime (1–32μg/mL), ceftazidime (2–32μg/ml), cefepime (2–16μg/ml), piperacillin/tazobactam (8/4 to 64/4μg/ml), ciprofloxacin (0.06–2μg/ml), levofloxacin (0.12–4μg/ml), gentamicin (4–8μg/ml), amikacin (8–32μg/ml), chloramphenicol (8–16μg/ml), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (2/38μg/ml), imipenem (0.5–8μg/ml), meropenem (1–16μg/ml), nitrofurantoin (32–64μg/ml), colistin (1–4μg/ml) and tigecycline (0.5–2μg/ml). E. coli ATCC 25922 was used for quality control in antimicrobial susceptibility testing. MIC50 and MIC90 were calculated for all antimicrobials based on the MIC of each strain. In this study, we define MDR as non-susceptibility to one or more antimicrobial agents in at least three different categories, as previously defined20.

Detection of mcr genes and molecular typing of colistin-resistant E. coli isolatesAll E. coli isolates with colistin MICs ≥4μg/ml were screened by multiplex PCR for the detection of mcr-1, mcr-2, mcr-3, mcr-4 and mcr-5 genes, as previously described16. DNA was extracted using the boiling bacterial lysis method. Clonal relatedness between isolates was determined by enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus-polymerase chain reaction (ERIC-PCR) and repetitive element palindromic-polymerase chain reaction (REP-PCR), as the previously established32.

Statistical analysisThe Statistical Packages of Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 22.0, was used for the statistical analysis. Pearson's chi-squared test was used to determine the relationship between strains based on the presence of the mcr-1 gene. Statistical significance was defined as p <0.05.

ResultsPresence of colistin-resistant E. coli and the mcr-1 geneOf 140 rectal swab samples analyzed, 23 (16.4%) showed growth on colistin-supplemented McConkey. All these isolates were confirmed to be E. coli and the presence of the mcr-1 gene was detected in all of them. Prevalence of mcr-1-positive E. coli for weaning piglets was 27.7% (95% CI; [11%;49%]), followed by 14.3% (95% CI; [5%;36%]) for growing pigs, and 12.9% (95% CI; [3%;34%]) for fattening pigs. The analysis of the remaining colistin resistance genes showed the absence of the mcr-2, mcr-3, mcr-4, and mcr-5 genes.

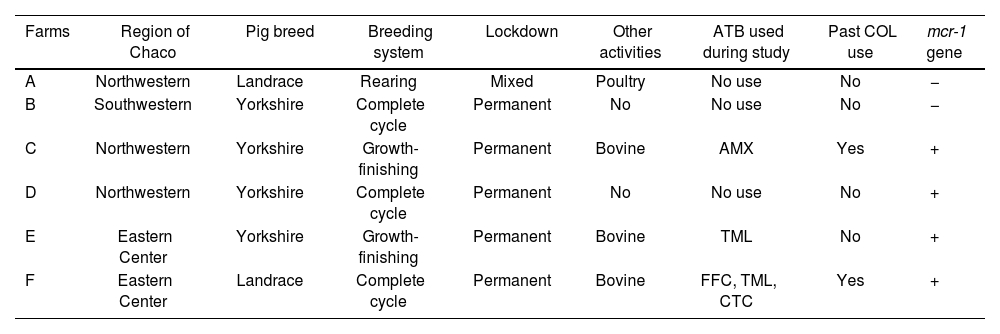

Of the total number of farms analyzed, three were located in the northwestern part of the province, two in the eastern central region and one in the southwestern zone. At least one mcr-1-positive isolate was detected in 66.7% of the pig farms studied (4/6), three of which engaged in another type of activity, such as bovine production. Farms with mcr-1 positive isolates were located in two of three agricultural regions of Chaco, Argentina. At the same time, only three farms reported the use of at least one antibiotic during pig fattening and, in particular, two farms had used colistin as a growth promoter in the past (Table 1).

Epidemiologic characteristics of the intensive pig farms studied.

| Farms | Region of Chaco | Pig breed | Breeding system | Lockdown | Other activities | ATB used during study | Past COL use | mcr-1 gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Northwestern | Landrace | Rearing | Mixed | Poultry | No use | No | − |

| B | Southwestern | Yorkshire | Complete cycle | Permanent | No | No use | No | − |

| C | Northwestern | Yorkshire | Growth-finishing | Permanent | Bovine | AMX | Yes | + |

| D | Northwestern | Yorkshire | Complete cycle | Permanent | No | No use | No | + |

| E | Eastern Center | Yorkshire | Growth-finishing | Permanent | Bovine | TML | No | + |

| F | Eastern Center | Landrace | Complete cycle | Permanent | Bovine | FFC, TML, CTC | Yes | + |

ATB: antibiotic; COL: colistin; AMX: amoxicillin; TML: tiamulin; FFC: florfenicol; CTC: chlortetracycline.

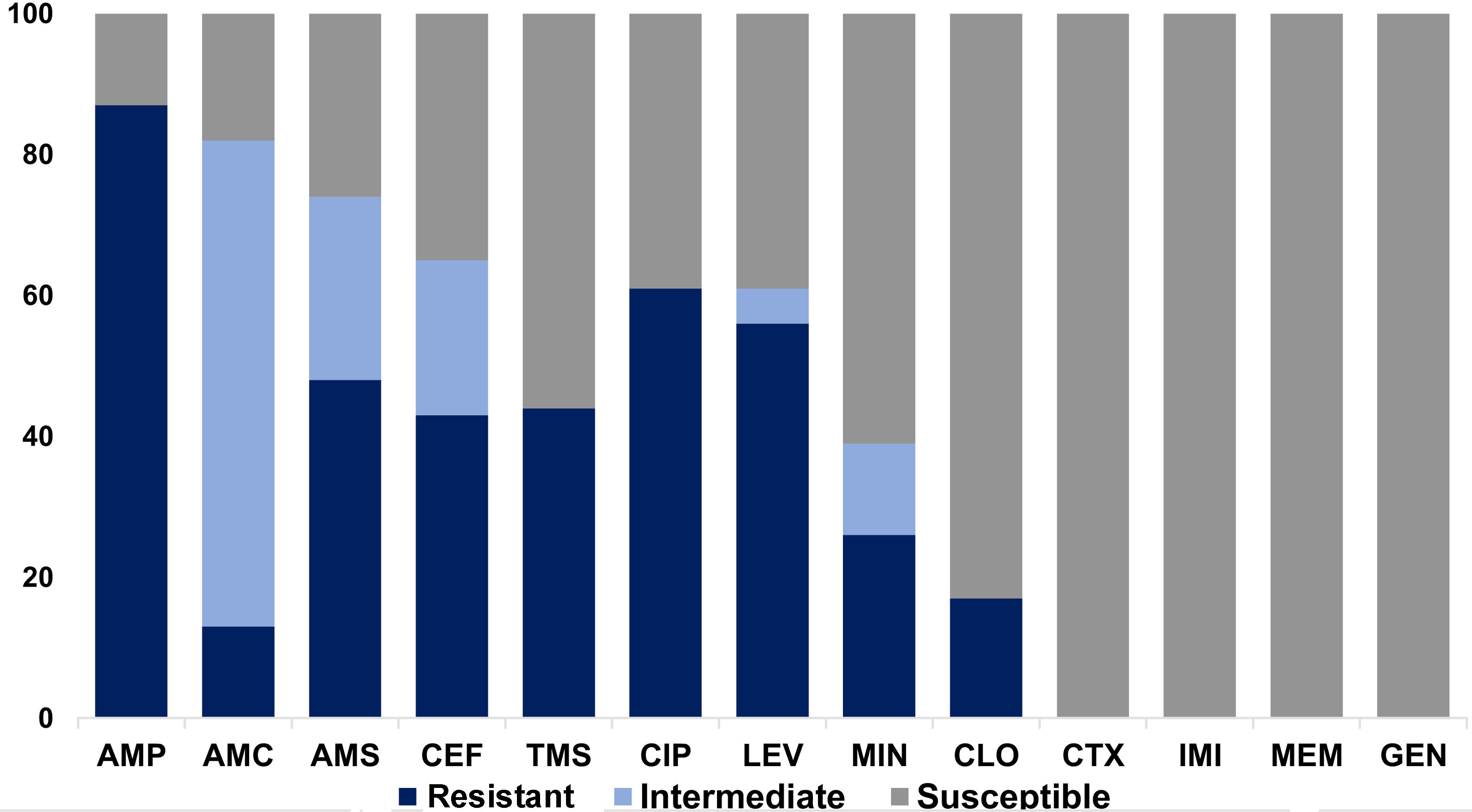

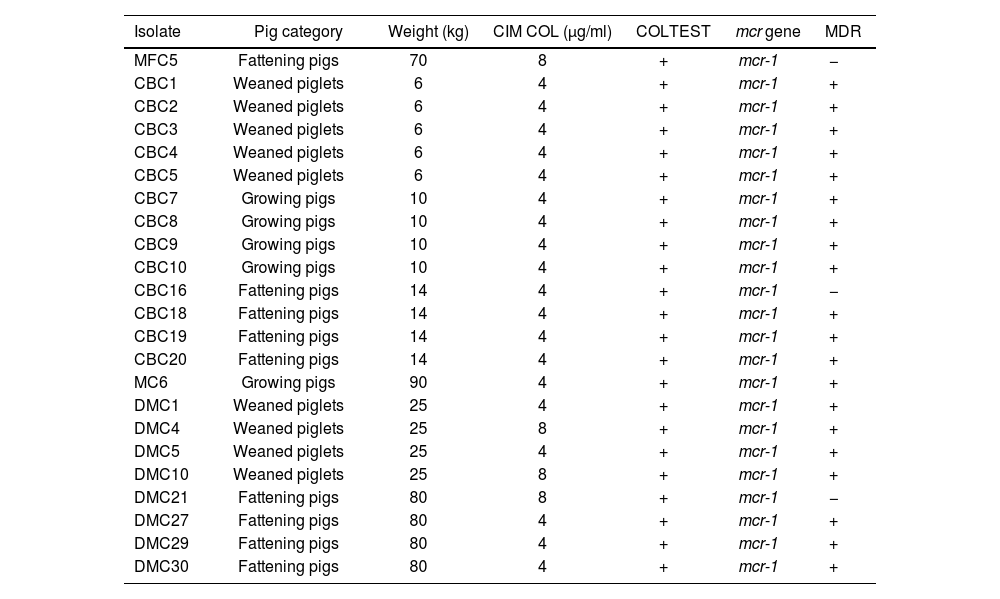

Colistin MIC values showed a bimodal distribution with a range of 4–8μg/ml and a MIC value of 4 was observed in 82.6% (19/23) of the isolates (Table 2). The observed resistance profile was as follows: ampicillin, 87% (95% CI; [66%;97%]); ampicillin–sulbactam, 47.8% (95% CI; [27%;69%]); amoxicillin–clavulanic, 13% (95% CI; [3%;34%]); chloramphenicol, 82.6% (95% CI; [61%;95%]); ciprofloxacin, 60.9% (95% CI; [38%;80%]); levofloxacin, 56.5% (95% CI; [34%;77%]); minocycline, 26.1% (95% CI; [10%;48%]) and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, 43.5% (95% CI; [23%;65%]). In contrast, 100% of the isolates were susceptible to cefotaxime, ceftazidime, meropenem, imipenem, gentamicin, amikacin, nitrofurantoin, fosfomycin and tigecycline (Fig. 1).

Characterization of colistin-resistant E. coli isolates (n=23).

| Isolate | Pig category | Weight (kg) | CIM COL (μg/ml) | COLTEST | mcr gene | MDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFC5 | Fattening pigs | 70 | 8 | + | mcr-1 | − |

| CBC1 | Weaned piglets | 6 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| CBC2 | Weaned piglets | 6 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| CBC3 | Weaned piglets | 6 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| CBC4 | Weaned piglets | 6 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| CBC5 | Weaned piglets | 6 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| CBC7 | Growing pigs | 10 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| CBC8 | Growing pigs | 10 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| CBC9 | Growing pigs | 10 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| CBC10 | Growing pigs | 10 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| CBC16 | Fattening pigs | 14 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | − |

| CBC18 | Fattening pigs | 14 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| CBC19 | Fattening pigs | 14 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| CBC20 | Fattening pigs | 14 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| MC6 | Growing pigs | 90 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| DMC1 | Weaned piglets | 25 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| DMC4 | Weaned piglets | 25 | 8 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| DMC5 | Weaned piglets | 25 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| DMC10 | Weaned piglets | 25 | 8 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| DMC21 | Fattening pigs | 80 | 8 | + | mcr-1 | − |

| DMC27 | Fattening pigs | 80 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| DMC29 | Fattening pigs | 80 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | + |

| DMC30 | Fattening pigs | 80 | 4 | + | mcr-1 | + |

MDR: multidrug-resistant.

Antimicrobial susceptibility profile of mcr-1-positive E. coli isolates to other antibiotics. AMP: ampicillin; AMC: amoxicillin/clavulanic; AMS: ampicillin–sulbactam; CEF: cefalotin; TMS: trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole; CIP: ciprofloxacin; LEV: levofloxacin; MIN: minocycline; CHL: chloramphenicol; CTX: cefotaxime; IMI: imipenem; MER: meropenem; GEN: gentamicin.

On the other hand, 12 phenotypic resistance patterns were observed in 23 mcr-1-positive E. coli isolates analyzed. Eighty-seven percent (87%) (95% CI; [66%;97%]) of the strains were classified as MDR based on previously defined criteria (Table 2). However, molecular typing of the isolates studied revealed a wide diversity of ERIC and REP profiles and no similarity in these patterns was observed.

DiscussionIn recent years, many studies have highlighted an increase in colistin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates in both humans and animals14,31. Recently, the mcr-1 gene has been reported in different types of food-producing animals such as pigs and poultry in Argentina6. Therefore, in the present study, we analyzed the prevalence of mcr-1-positive E. coli isolates in pig farms in Chaco, Argentina. To the best of our knowledge, our manuscript highlights the first report of the mcr-1 gene within the pig production chain in northeastern Argentina, despite the fact that the use of colistin as a growth promoter has been suspended.

Previous studies in pigs have shown that the frequency of mcr-1 was 0.5–9.9% in Europe23,26 and 20.6% in China18. In Latin America, the circulation of mcr-1-harboring E. coli strains in swine showed a prevalence of 47% in Ecuador34, while in Peru and Brazil it was 12% and 3.1%, respectively4,10. In January 2019, the Ministry of Agriculture of Argentina published Resolution No. 22/2019, which prohibits the use of colistin and its derivatives in food-producing animals28. Prior to this resolution, the prevalence of mcr-1-positive E. coli isolates in swine from Argentina was 38.7%8. However, in our study we found the mcr-1 gene in 16% of pigs tested between 2020 and 2021. These results showed a significant decrease in the prevalence of mcr-1 carrying E. coli in pig production, which could be due to the prohibition of colistin for veterinary use in our country.

In Argentina, the most frequently utilized antimicrobial classes in pigs include beta-lactams (e.g., amoxicillin, ceftiofur), macrolides (e.g., tylosin), tetracyclines (e.g., oxytetracycline, chlortetracycline), and fluoroquinolones (e.g., enrofloxacin and norfloxacin)11. When comparing the three stages of pig production, it was found that weaning piglets had a significantly higher resistance rate to colistin than other stages. This may be explained by the fact that more than 70% of the antimicrobial agents used in pigs are administered during the first 10 weeks of life22. Therefore, our results suggest that weaning piglets could act as an important reservoir for the mcr-1 gene. Furthermore, this study showed that three pig farms presented mcr-1 positive isolates and were simultaneously engaged in another type of activity such as bovine production. This situation is worrying because it could contribute to the spread of multidrug-resistant microorganisms carrying mcr-1 from pigs to cattle, thereby affecting a new production chain in the region.

The analysis of the mcr genes by PCR in colistin-resistant E. coli isolates showed that they all carried solely mcr-1. In concordance with our results, mcr-1 is the only gene reported so far in pig farms in Argentina8 and, as far as we know, in other farm animals6 and even in pets27. Molecular typing of mcr-1-positive E. coli strains revealed the presence of a wide diversity of ERIC and REP profiles, indicating that these microorganisms are probably not clonally related. This finding could be attributed to the fact that the establishments under investigation are situated in geographically distinct locations, with no connection between the production sites and animals, resulting in the emergence of distinct clones. In addition, antimicrobial susceptibility to other antibiotics showed that 87% of mcr-1-positive E. coli isolates were classified as MDR, in agreement with a previous study describing a high prevalence of MDR (71%)8.

Current data indicate a higher prevalence of mcr-carrying bacteria in animals than in humans. This supports the hypothesis that colistin resistance encoded by mcr-1 is most commonly transferred from animals to humans19. It is important to clarify that fewer studies have been conducted in humans than in animals. In Argentina, only one retrospective multicenter study of human samples from 2012 to 2018 has been reported. A total of 192 human isolates of mcr-1-positive E. coli were analyzed, only one (0.5%) of which was from the province of Chaco9. Therefore, it would be of great interest to conduct further studies on mcr-1-mediated colistin resistance in humans and the environment in our region. This would allow a better understanding of the transmission cycle of the mcr-1 gene from a One Health perspective.

Finally, our study showed the presence of the mcr-1 gene from pig farms in the province of Chaco. This is of great concern because this province is the fourth largest producer of pork in Argentina. Accordingly, this situation could contribute to the spread of multiresistant microorganisms carrying mcr-1 in the pig production chain from northeastern Argentina. Some limitations of the present study should be mentioned. First, circulating allelic variants of the mcr-1 gene were not identified. Secondly, we did not investigate the mcr-6, mcr-7, mcr-8, mcr-9 and mcr-10 genes, which are also involved in colistin resistance.

ConclusionThe results of this study show a high prevalence (16%) of mcr-1-positive E. coli from COL-free intensive pig farms in the province of Chaco, Argentina. The mcr-1-positive E. coli isolates exhibited diverse resistance profiles with 87% MDR and high clonal diversity. Our study suggests that healthy pigs may act as mcr-1 carrying E. coli reservoirs. Therefore, active surveillance of antimicrobial resistance and strict monitoring of biosecurity measures are necessary in the pig farms studied, which will prevent the spread and dissemination of the mcr-1 gene in the pig production chain.

FundingThis study was funded by the University of the Northeast Argentine.

Conflict of interestThe authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.