Urgent and unexpected findings are very common in oncology and haematology patients. This article reviews the most important points included in the European Society of Radiology’s guidelines and proposes a practical approach to reporting and communicating these findings more efficiently. This approach is explained with illustrative examples. Radiologists can provide added value in the management of these findings by helping referring clinicians reach the best decisions. To this end, it is essential to know the imaging manifestations of the most common findings that must be reported urgently, such as the specific toxicity of different treatments, the complications of tumours and catheters, infections, and thrombosis. Moreover, it is crucial to consider the individual patient’s treatment, risk factors, clinical situation, and immune status.

Los hallazgos urgentes e inesperados son muy frecuentes en los pacientes oncohematológicos. En este artículo repasamos los puntos más importantes de la guía de la European Society of Radiology y planteamos propuestas prácticas para realizar el informe y comunicar estos hallazgos más eficientemente, ilustradas mediante ejemplos. El radiólogo puede aportar un valor añadido en el manejo de estos hallazgos cuando ayuda al médico que ha solicitado la prueba a tomar la mejor decisión. Para ello es esencial conocer las manifestaciones por imagen de los hallazgos más frecuentes, que además deben comunicarse de forma urgente, como son la toxicidad específica de los tratamientos, las complicaciones de los tumores y de los catéteres, las infecciones y las trombosis; y hay que tener en cuenta el tratamiento recibido, los factores de riesgo y la situación clínica e inmunológica de cada paciente.

Urgent and unexpected findings in imaging tests present a challenge to radiologists in their day-to-day workload, and they need clear guidelines on how to manage them. They take extra time and effort, partly because they occur so frequently (one in every four computed tomography [CT] studies), but also because they are so varied, as different strategies are required to deal with each case.1,2 Searching the literature does not always help as it is very extensive and coverage of the problem is fragmented and not very pragmatic, and this can lead to inconsistent compliance with guidelines.3 As a result, radiologists may not be sure they are communicating findings in the best possible way.

In the specific case of oncology and haematology patients, these findings have their own added challenges. First of all, cancer patients represent a very significant proportion of the examinations carried out in radiology departments, so many of the unexpected findings involve them. Moreover, in oncology and haematology patients these findings are clinically important and more often require urgent action compared to other patients.1 With the increasing complexity of cancers and their treatments, radiologists may be uncertain about the prognosis for some complications, not knowing how to interpret them and how to proceed. Last of all, from a medical-legal point of view, the findings that most concern the radiologist, the doctor requesting the test and the patients themselves are those which may indicate cancer.4,5

This article focuses on the practical management of urgent and unexpected findings in oncology and haematology patients. We review the most relevant aspects of the European guidelines and discuss the most common findings in these patients. We make practical suggestions for preparing the report and recommendations for communicating the findings more efficiently.

What do the European Society of Radiology guidelines say?The guidelines of the various professional radiology associations contain different definitions of unexpected finding, and in some cases the recommendations are contradictory. These guidelines adopt different approaches depending on the clinical significance of the finding, the need for additional action and its potential importance and/or depending on its location.6–9

The most important guidelines in our environment are those of the European Society of Radiology (ESR),6 which fortunately have a very practical approach. Although they date from 2012, they are still fully valid and the challenges they pose still apply. Discussing the contents of these guidelines is outside the scope of this manuscript, but they have two key aspects:

- 1

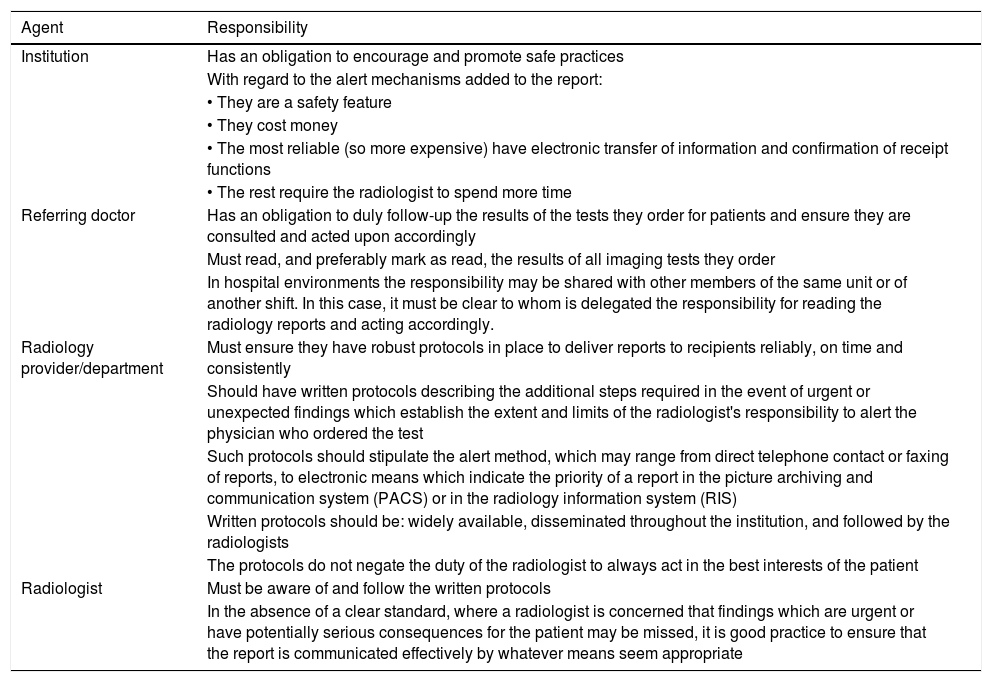

They assign responsibility for communicating unexpected findings in radiological tests to various agents: the institution; the ordering physician; the radiology department; and the radiologist. In addition, they clearly describe the responsibility of each agent (Table 1).

Table 1.Agents involved in managing unexpected findings according to European Society of Radiology guidelines.6 On the right, each agent's responsibilities.

Agent Responsibility Institution Has an obligation to encourage and promote safe practices With regard to the alert mechanisms added to the report: • They are a safety feature • They cost money • The most reliable (so more expensive) have electronic transfer of information and confirmation of receipt functions • The rest require the radiologist to spend more time Referring doctor Has an obligation to duly follow-up the results of the tests they order for patients and ensure they are consulted and acted upon accordingly Must read, and preferably mark as read, the results of all imaging tests they order In hospital environments the responsibility may be shared with other members of the same unit or of another shift. In this case, it must be clear to whom is delegated the responsibility for reading the radiology reports and acting accordingly. Radiology provider/department Must ensure they have robust protocols in place to deliver reports to recipients reliably, on time and consistently Should have written protocols describing the additional steps required in the event of urgent or unexpected findings which establish the extent and limits of the radiologist's responsibility to alert the physician who ordered the test Such protocols should stipulate the alert method, which may range from direct telephone contact or faxing of reports, to electronic means which indicate the priority of a report in the picture archiving and communication system (PACS) or in the radiology information system (RIS) Written protocols should be: widely available, disseminated throughout the institution, and followed by the radiologists The protocols do not negate the duty of the radiologist to always act in the best interests of the patient Radiologist Must be aware of and follow the written protocols In the absence of a clear standard, where a radiologist is concerned that findings which are urgent or have potentially serious consequences for the patient may be missed, it is good practice to ensure that the report is communicated effectively by whatever means seem appropriate - 2

They provide different definitions for urgent findings and unexpected findings, and recommend different courses of action for them. In the case of oncology and haematology patients, this classification is more functional than those of other guidelines:

- a)

Urgent findings are those that may cause harm to the patient if urgent action is not taken. The course of action will depend on whether it is an expected finding or not. It is necessary to contact (usually by telephone) the referring doctor or someone who can take the appropriate measures directly.

- b)

Unexpected findings are significant abnormalities on studies performed for an unrelated reason, which require prompt action by the referring physician. Direct telephone communication is not usually necessary and other methods (electronic notifications, email or others) may be used.

- a)

In general, following the guidelines makes it easier to make evidence-based decisions and minimises medical-legal issues.10 However, for most incidental findings, there is a lack specific guidelines for action. For example, there are no guidelines for oncology and haematology patients, and these patients are even expressly excluded from some of the guidelines in use.2,11

The approach of the European guidelines is especially pertinent in the case of oncology and haematology patients, whose management is multidisciplinary, as it establishes that the radiologist cannot and should not be the only person responsible for making decisions and managing the communication of these findings.

General principles on urgent and unexpected findings in oncology and haematology patientsUrgent findingsProcedures for communicating urgent findings must be simple and safe, and the radiologist must know who to contact and how. This information must be in writing and available to all radiologists. To ensure that these communication channels always work, they need to be agreed in advance with the services that make the requests. It has to be taken into account that different services may have particular features that determine the most appropriate route. For specialists who are always physically in a specific space (radiotherapy for example), the responsible doctor can be located through an administrative assistant. However, for specialists who may be in different places or who are not always available by phone (for example surgery), it is more efficient to call a pager or agree that the finding will be communicated to any specialist in the same unit or section. It must also be agreed in advance how the findings will be communicated outside morning hours (through the on-call doctor for face-to-face services or services scheduled in the afternoon, or through the Accident and Emergency department for frequent urgent findings such as pulmonary thromboembolism, etc).

Unexpected findingsIn the case of cancer patients, unexpected findings are so common that we should not be thinking "what would we do if we found them", but rather have already planned "what we do when we find them".

As in the previous case, this action plan needs to be agreed in advance with the services referring patients, taking into account their needs and establishing channels of communication and feedback (formal and informal) that enable us to adapt the circuits as necessary. In some centres referring nursing staff will need to be included in the communication (where applicable and when their role involves the receipt of these findings) and/or the impact on patients will need to be considered (as increasingly they are able to access their radiological reports through their electronic medical records).10,11

Radiologists provide added value when they prioritise pragmatism and efficiency in their approach to radiology, understanding the clinical case and acting as an expert diagnostic consultant, including actionable recommendations in their report. In medicine, information only has value and purpose when it affects a decision. In the case at hand, specific reports focusing on the most appropriate recommendations (what test to request or which specialist to consult) are preferable to those that contain extensive differential diagnoses or are long on incidental findings without clinical significance.10,12 The importance of an unexpected finding depends on the context of the patient (age, situation and prognosis of the underlying disease, therapeutic options, comorbidity, etc), so the radiologist has to consult their medical records and be familiar with the different types of cancer and their treatments. For a general radiologist, it can be difficult to distinguish between findings that can be disregarded and those that are going to require monitoring and, in particular, those that require further investigation.1,5,13

As far as the electronic alert systems implemented in some centres are concerned, in order to be safe, they must incorporate systems to confirm receipt of the notification. Any other system used to report these findings must be traceable.14,15

Most common findings in oncology and haematology patients. Practical considerationsIn parallel with the increase in the number of CT and MRI scans being performed on patients, there is increased interest in incidental findings and the number of lesions found in these studies which "may or may not" be cancer. Still today, most of these findings continue to be cancer-related and are unsuspected neoplasms.1,2

In oncology and haematology patients, apart from recurrences and second primary tumours, the majority of urgent and unexpected findings are thrombosis, infections, treatment complications and cancer-related complications.13 Below we provide relevant practical advice for the management of the most common of these, along with illustrative examples of CT findings, as unexpected findings are most often detected by CT.1,2

Unexpected finding of an unknown neoplasmThis the most common unexpected cancer-related finding in all radiology departments and there must be processes in place to guarantee that the referring physician hears about the finding promptly.2,6 It is recommended to include as much staging information as possible and, if necessary, recommendations on how to complete the investigations.12 We have to keep in mind that, in some centres, patients can access their radiological reports through their electronic medical records.11,16

Cancer recurrenceThe diagnosis of a recurrence during cancer follow-up is not an unexpected finding, but it must still be ensured that the referring physician receives the report promptly. When recurrence is detected incidentally on a study performed for another reason, the same principles apply as for an unknown neoplasm.

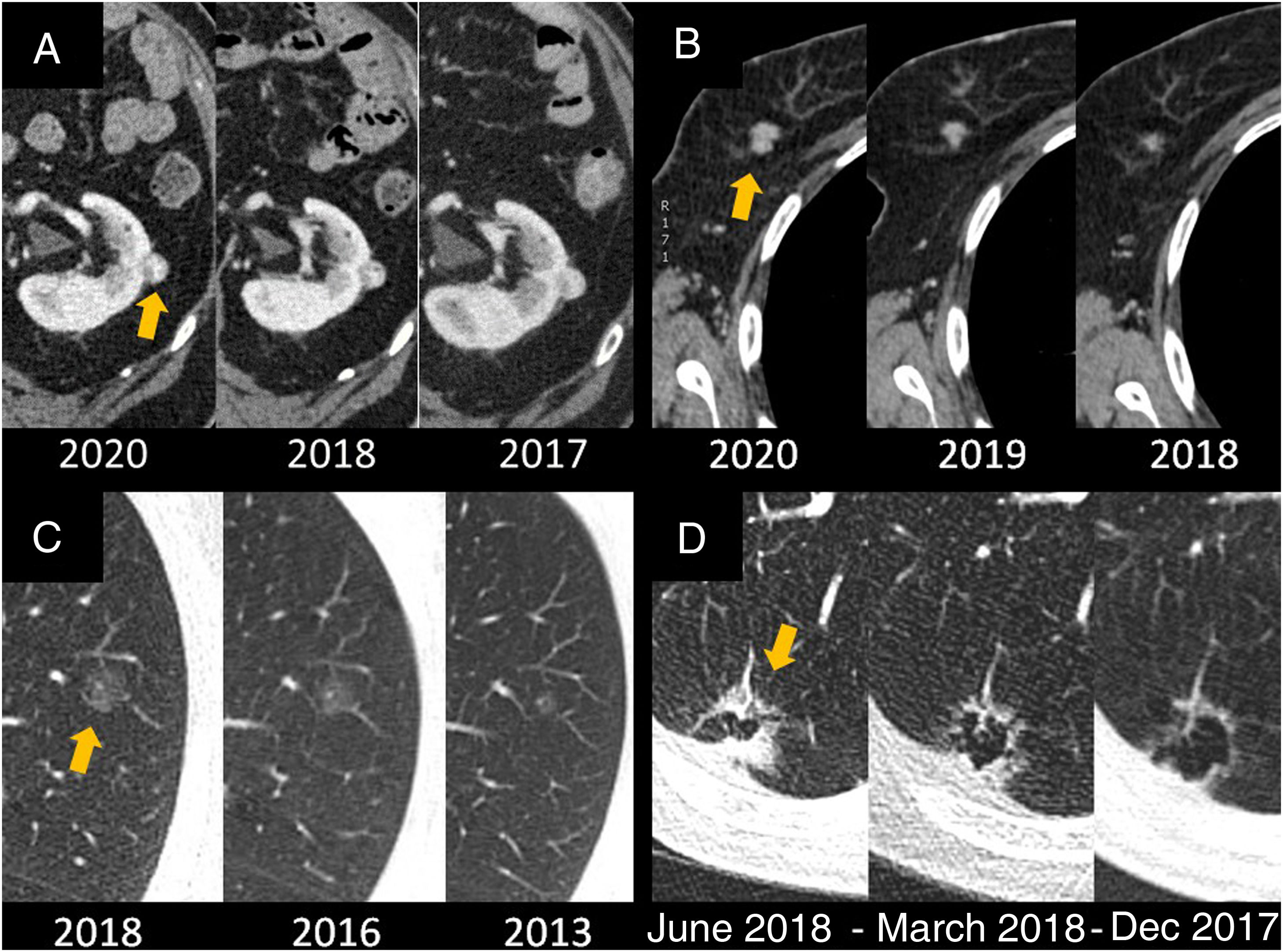

Second primary (metachronous cancer)The unexpected finding of a metachronous tumour is relatively common in patients who have had cancer; the prevalence of second primary tumours is as high as 9%.17 The course of action is the same as for cancer recurrence, but when the referring physician is not familiar with the type of neoplasm found, it is pertinent to include the appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations in the radiological report.12,13,18. It is important to remember that in these patients any diagnostic and therapeutic decision will be dictated by the situation with the underlying cancer and, depending on their prognosis, it may be indicated to simply continue monitoring the second cancer by imaging19,20 (Fig. 1).

Second neoplasm as an unexpected finding. A) Left renal neoplasm diagnosed during follow-up of a colon adenocarcinoma. A watchful waiting approach has been followed and the renal neoplasm has not grown over the course of these years. B) 12-mm spiculated nodule in the right breast compatible with metachronous breast cancer in stage cT1c N0 M0, detected during follow-up for a kidney tumour. The urologist was advised to refer the patient to the breast disease unit and the biopsy of the nodule showed an infiltrating ductal carcinoma. C) Lesion in the spectrum of primary lung adenocarcinoma in the left upper lobe (cTis) detected during follow-up of a rectal adenocarcinoma. Slow-growing ground-glass nodule on serial CT scans; referral to the lung cancer clinic was recommended. Performing a PET/CT would not contribute anything to the diagnosis, these lesions do not usually show hypermetabolism of glucose and a negative PET would not rule out malignant origin. It was resected and corresponded to a lung adenocarcinoma pT1a N0 M0. D) Metachronous lung adenocarcinoma over a cystic space in the right lower lobe (cT1-T2 N0 M0) detected during follow-up of a contralateral lung adenocarcinoma disease-free since 2016. The spiculated lesion grew rapidly over a complex cyst and was treated with stereotactic radiotherapy.

- □

In addition to detecting and characterising the lesion, the radiologist can stage it and help manage it, particularly if the test was ordered by someone not familiar with the second neoplasm.

- □

Giving information about lesions which can be biopsied and whether or not they are accessible by interventional radiology can help speed up the diagnostic process.

- □

Both the type of cancer and the patient's context will dictate the therapeutic decisions. Depending on the stage and interval since the initial cancer, close follow-up may be an option.

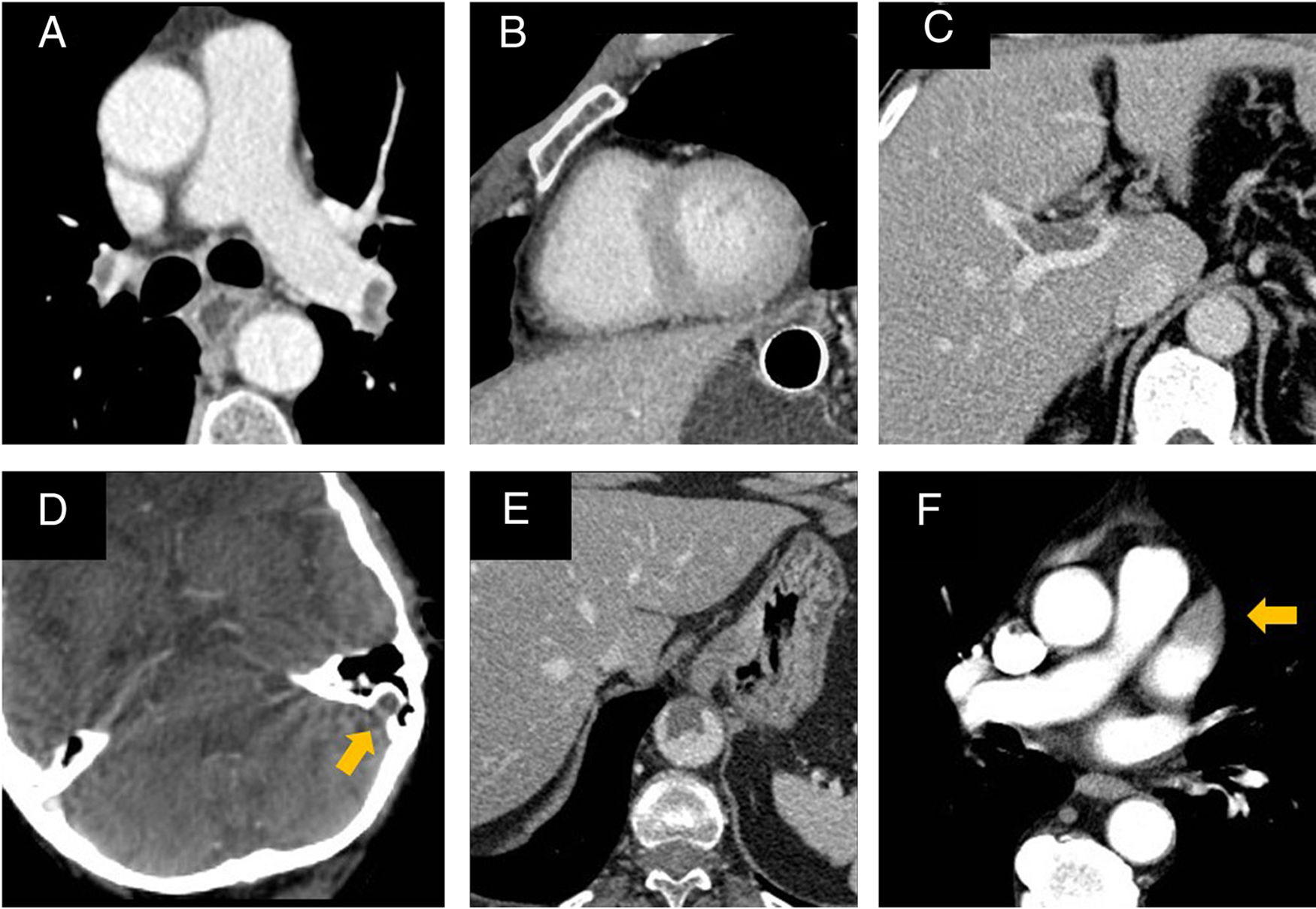

Thromboses are a highly prevalent unexpected finding in oncology and haematology patients and they cause significant morbidity, usually requiring urgent treatment.21 Cancer is a state of hypercoagulability and patients with some tumours (gastric, pancreatic, brain, etc), permanent central venous catheters and/or receiving certain treatments (bevacizumab, cisplatin, gemcitabine, immunomodulators, etc) are at even higher risk22 (Fig. 2). It should be noted that the concept of overdiagnosis of subsegmental pulmonary emboli is not applicable to patients with active cancer.23 In these patients, any pulmonary embolism is potentially serious and requires treatment.24

Thrombi found unexpectedly in cancer patients. A) Bilateral pulmonary thromboembolism found in a portal phase CT to assess the response to chemotherapy of a metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma. B) In the same study, radiological signs of overloading of the right cavities were observed (inversion of the RV/LV ratio and rectification of the interventricular septum). These findings should be communicated immediately. C) Portal thrombosis in the CT performed at the end of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon adenocarcinoma. The patient was anticoagulated until resolution of the thrombus. D) Thrombosis from the jugular vein to the left transverse sinus due to compression by left supraclavicular lymphadenopathy in a patient with colon adenocarcinoma. Anticoagulation will be maintained as long as the cause of the thrombosis persists. E) Aortic thrombus developed during chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatment for small cell lung carcinoma; the patient suffered a stroke with an embolic profile. F) Thrombus in the atrial appendage detected during follow-up for adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient was referred to cardiology, which confirmed the finding. Atrial appendage thrombi are a significant cause of embolic strokes and usually require long-term anticoagulation.

- □

Thromboses should always be considered an urgent finding. They must be reported immediately to the referring physician, regardless of whether or not the patient is on anticoagulation therapy.25

- □

It is advisable to agree in advance with oncology and haematology how these findings should be communicated during periods when they are not available (for example evenings and weekends).

- □

If further specific investigations are recommended, this should also be passed on promptly.

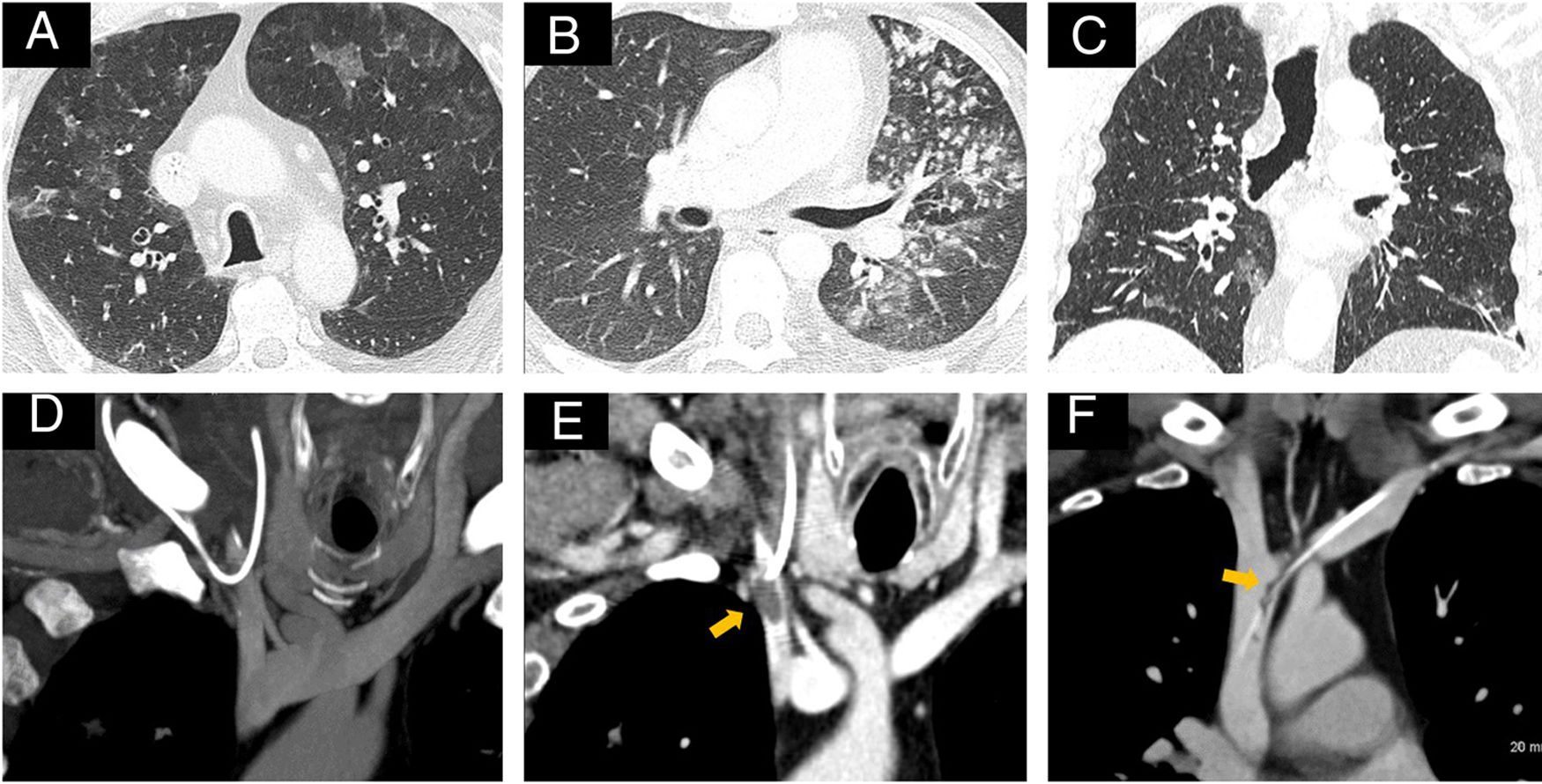

Cancer is a systemic disease and immunosuppression is one of its manifestations.26 In addition, many cancer and supportive therapies, and venous access devices, increase the risk of infection.27 Sometimes these same treatments cause the clinical manifestations of infections to be delayed and/or masked, and the first indication may therefore be the radiological findings.

Radiological manifestations of infections can be indistinguishable from other abnormalities, so it is important to maintain a high index of suspicion, be aware of the patient's immune status, and perform a good differential diagnosis.27 The most common infections are of the respiratory, urinary and gastrointestinal tracts, cholangitis and abscesses (Fig. 3).

Unexpected finding of catheter infections and complications. A) Patient with cutaneous lymphoma treated with alemtuzumab (immunosuppressant) who had reactivation of cytomegalovirus. Bilateral cytomegalovirus pneumonia detected on response assessment CT. Bilateral ground-glass opacities of peripheral distribution and predominance in upper fields can be the radiological manifestation of many infections and the toxicity of many drugs. B) Tuberculous reactivation with bacilli-bearing endobronchial dissemination detected in the CT to assess the response to chemotherapy of a metastatic breast carcinoma. Cavitary consolidation in the left upper lobe with necrotic lymph nodes (not shown) and multiple small nodules in a patient with a history of tuberculosis. The finding was made on a public holiday and the patient was referred to Accident and Emergency by telephone. C) Bilateral pneumonia due to COVID-19 with predominantly peripheral and ground glass infiltrates in the bases of both lungs; it was detected during the follow-up of a resected renal cell carcinoma. Urology contacted the patient and referred him to Accident and Emergency; he passed away four weeks later. D) Displacement of the end of the catheter from the right pectoral reservoir to the jugular vein. E) Same patient, thrombus in the confluence of the jugular and subclavian veins. F) Fibrin sheath around the distal end of the subcutaneous catheter reservoir in the superior vena cava; the reservoir allowed injection, but did not reflux.

- □

Radiological findings compatible with an unsuspected infection should always be reported urgently due to their potential severity.

- □

Some cancer treatments and steroids depress cell-mediated immunity and benefit the reactivation of tuberculosis and fungi.

- □

We need to be aware of the patient's immune status and risk factors in order to make a good suspected diagnosis and enable early initiation of specific treatment.

- □

The epidemiological context is important. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, we need to maintain a high index of suspicion and warn of radiological findings compatible with this infection.

Oncology and haematology patients frequently have vascular access devices for treatment administration, such as peripherally inserted central catheters, subcutaneous reservoirs and tunnelled central catheters. Acute complications related to the insertion are usually detected during the procedure (pneumothorax, malpositioning, rupture, mediastinal haematoma, etc). However, late complications tend to be detected incidentally on CT scans (mainly thrombosis, pericatheter fibrin sheaths and infection)28 (Fig. 3). It is important to know how to recognise and communicate them quickly.

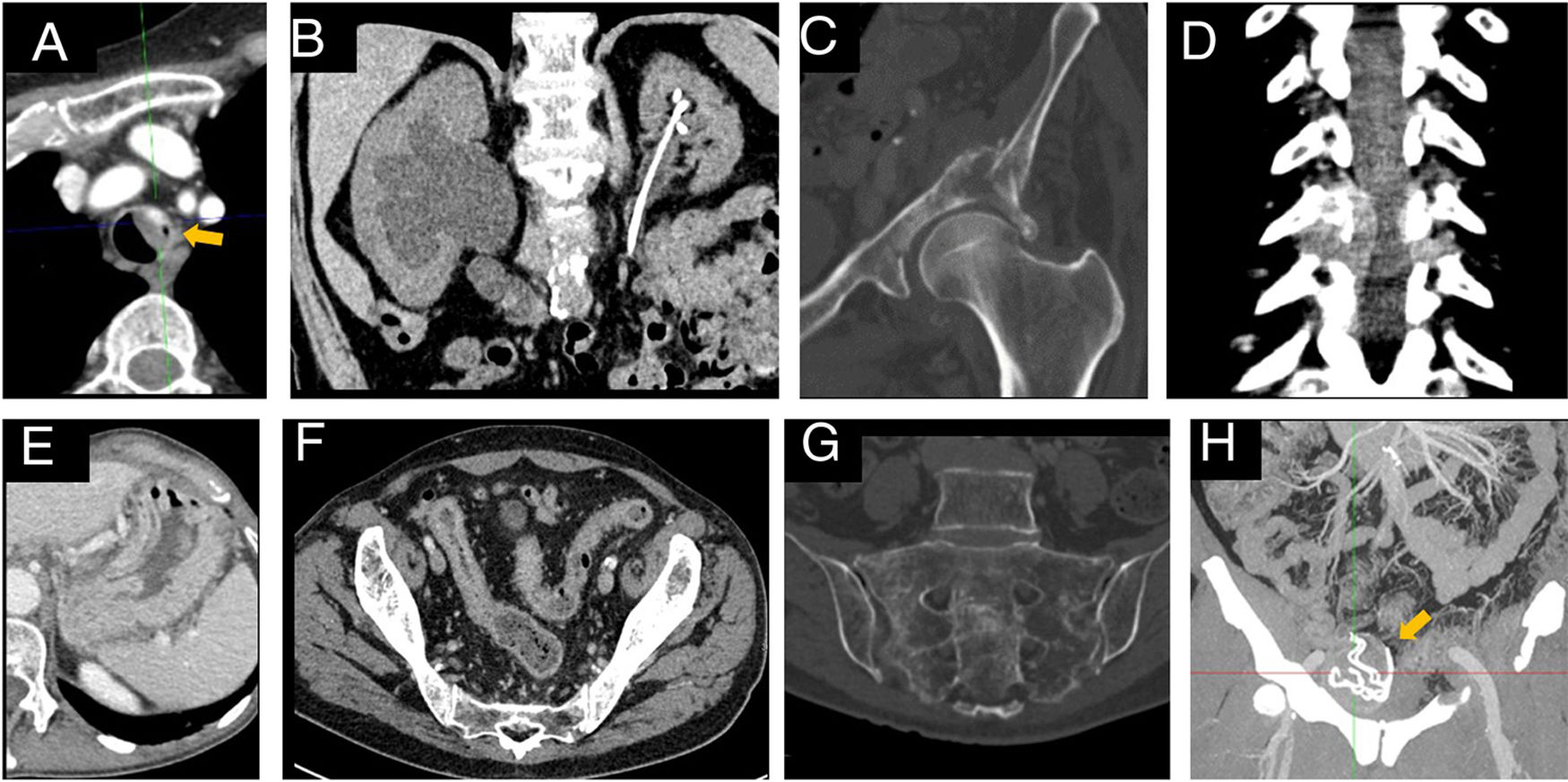

Complications of the cancerTests performed on patients with cancer show up many findings related to the underlying disease and it can be very difficult for the radiologist to decide which are unexpected and even which are urgent. The most common complications of cancer are obstruction of the urinary, gastrointestinal or respiratory tracts, pathological fractures, superior vena cava syndrome, spinal cord compression, perforations due to tumour necrosis and tumour bleeding.29 If patients are taking analgesics and/or steroids, the clinical manifestations may be masked, leading them to be unexpectedly diagnosed on imaging tests.

The information on the request form tends to be insufficient, so the medical records should be consulted whenever necessary and clinical judgement should be used. When in doubt, it is preferable to over-report these findings. In the medium term, a relationship of close collaboration with the other departments can provide the feedback needed to improve the quality of inter-service communication and to avoid unnecessary alerts that can result in a waste of time and effort on both sides (Fig. 4).

Unexpected complications of the tumour and the treatment that require urgent treatment. A) Hypervascular metastasis of a solitary fibrous tumour in the left wall of the trachea with airway stenosis and risk of bleeding. Received radiotherapy. B) Grade 5 right ureterohydronephrosis due to progression of locally advanced cervical cancer. Response assessment CT performed without contrast due to glomerular filtration less than 10 ml/min in the analysis performed on the same day. Although unilateral obstructive uropathy does not usually cause severe renal failure, in this case it affected the functioning kidney (left renal atrophy despite the left double-J catheter due to ureteral entrapment). C) Metastasis in the left half of the pelvis with a complex pathological fracture that affected the iliac blade and the acetabulum. The patient, who was taking strong painkillers, could not remember when the fracture occurred and was able to walk. D) Same patient, lytic metastasis of small cell lung carcinoma in the right posterior elements of T6 with soft tissue mass causing stenosis of the spinal canal and foramina. Thoracic spinal cord compression requires urgent radiotherapy (or surgery). E) Immune-mediated gastritis secondary to pembrolizumab; to reach the diagnosis it was necessary to have a high index of suspicion because the clinical manifestations are usually latent. The image shows prominence of the gastric folds with wall thickening and mucosal enhancement. Although the findings were nonspecific, they were a change from previous studies. F) Immune-mediated colitis secondary to pembrolizumab; the image shows the parietal thickening of the colon with mucosal enhancement, inflammatory changes in the fat, and engorgement of the mesenteric vessels. This complication is potentially serious and the medical oncology "pager" was notified. G) Multiple sacral insufficiency fractures found during follow-up of a rectal adenocarcinoma treated with preoperative radiotherapy. Being aware of the treatment received is enough to diagnose them correctly. H) Retained surgical item found during follow-up of a resected renal cell carcinoma. It was a retained swab from an inguinal hernia repair. It can be seen as a new oval lesion medial to the external iliac vessels, with capsule and metallic threads (best visualised in the maximum intensity projection). This finding was reported to both the urologist who ordered the CT scan and the surgeon who performed the procedure.

- □

The cancer complications mentioned above should always be reported urgently.

- □

Consulting the medical records helps to decide whether the complications found are unexpected or not.

- □

Frequent dialogue with other specialists will improve the radiologist's ability to interpret and communicate these findings.

Cancer treatment is increasingly complex and the related complications are therefore more frequent and varied. Radiologists need to become familiar with these complications, as they may be the first to detect them.30–32 These cases have medical-legal implications and, as in any other examination, we have to be truthful and prudent with the reports, while also bearing in mind that the patients may read them through their electronic medical records11 (Fig. 4).

Key ideas- □

Before writing the report, we need to know about previous surgical interventions and what treatment the patient is receiving. In the case of systemic treatments (chemotherapy, immunotherapy, etc), toxicity and its imaging manifestations are specific to each drug. In the case of radiotherapy, we need to know which area has been treated, as well as with what dose and on what date.

- □

In patients treated with immunotherapy there is a need to maintain a high index of suspicion, as the clinical and radiological signs can be subtle.

- □

In addition to notifying the referring physician of the unexpected complication, as a professional courtesy it may be appropriate to inform the specialist who performed the procedure (or prescribed the drug) when they are from another department.

The volume of investigations performed on patients with cancer is so high that incidental findings not related to a patient's cancer are also common. In these cases, the same principles for communication apply, although understanding the clinical situation helps us make a detailed report which provides added value for patient care.

ConclusionsUrgent and unexpected findings are very common in oncology and haematology patients and add an extra degree of complexity for the radiologist when reporting their imaging studies. This task is simplified by following the ESR guidelines and improving communication with the services that refer cancer patients to us. We need to establish in advance, and in consensus with these specialists, how we are going to communicate these findings.

As radiologists, we can provide added value in the care of these patients with our recommendations. For this, it is essential that we are aware of what treatment the patients are receiving and the related risk factors, and that we consult each patient's medical records for information on their clinical and immune status. We need to be familiar with the particular manifestations in imaging studies of the most common findings which also need to be reported urgently, such as the specific toxicity of treatments, complications of tumours and catheters, infections and thrombosis.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for the integrity of the study: AVJ.

- 2

Study concept: AVJ.

- 3

Study design: AVJ.

- 4

Data collection: Not applicable.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: Not applicable.

- 6

Statistical processing: Not applicable.

- 7

Literature search: AVJ.

- 8

Drafting of the article: AVJ, SDF, EPP, RPC.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: AVJ, SDF, EPP, RPC.

- 10

Approval of the final version: AVJ, SDF, EPP, RPC.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.