Otosclerosis is a primary osteodystrophy of the temporal bone that causes progressive conductive hearing loss. The diagnosis is generally clinical, but multidetector CT (MDCT), the imaging technique of choice, is sometimes necessary. The objective of this article is to systematically review the usefulness of imaging techniques for the diagnosis and postsurgical assessment of otosclerosis, fundamentally the role of MDCT, to decrease the surgical risk.

La otosclerosis es una otodistrofia primaria del hueso temporal que produce una hipoacusia de transmisión progresiva. El diagnóstico es generalmente clínico, pero en ocasiones es necesaria la realización de una tomografía computarizada multidetector (TCMD), que es la técnica de imagen de elección. El objetivo de este artículo es realizar una actualización sistemática de la utilidad de las técnicas de imagen en el diagnóstico y la valoración posquirúrgica de la otosclerosis, fundamentalmente del papel de la TCMD, con el fin de disminuir el riesgo quirúrgico.

Otosclerosis is a primary otodystrophy characterized by abnormalities in the otic capsule osseous remodeling of the temporal bone.1–3 The otic capsule is made up of three layers of different ossification; among them, the intermedial layer typically shows endochondral ossification. Due to unknown causes, in patients with otosclerosis the endochondral bone is replaced by disorganized spongy bone, less dense and with a greater vascular component, which makes up the otospongiosis stage or active stage. As the disease evolves sometimes the pathologic spongy bone re-calcifies while showing a greater sclerosis component giving rise to otosclerosis or inactive stage.1,4–6

It is a genetic disease that is inherited by a dominant autosomal pattern, with incomplete penetrance and a variable clinical expression.2,3,5,6 Damage is bilateral in 80–85 per cent of the patients, shows female predominance (2:1) and its incidence peak is between the second and fourth decades of life.1–3,5,7 It is more frequent among caucasians,5 with a prevalence of around 0.3–0.4 per cent.2 Although there is no clear consensus, some studies8 confirm that the location and extension of the otosclerotic foci condition the diagnosis, and in particular the type of hearing loss of these patients.

The main symptom of the disease is a progressive hearing loss, usually bilateral that can be associated or not with tinnitus.1,3,7 Sometimes it can also occur as a mixed, or exceptionally, a pure sensorineural hearing loss.

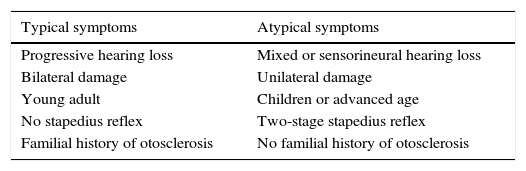

Diagnosis has been classically based on the presence of a compatible clinical diagnosis in a young adult patient, with normal otoscopy and a familial history of otosclerosis (Table 1).4

Types of clinical presentation.

| Typical symptoms | Atypical symptoms |

|---|---|

| Progressive hearing loss | Mixed or sensorineural hearing loss |

| Bilateral damage | Unilateral damage |

| Young adult | Children or advanced age |

| No stapedius reflex | Two-stage stapedius reflex |

| Familial history of otosclerosis | No familial history of otosclerosis |

To many ENT specialists there is no need to perform imaging modalities in typical cases1,9,10 and confirmation diagnosis is performed during surgery, when the otosclerotic foci are observed in the oval window with fixation of the stirrup.4,7 In atypical cases (Table 1) imaging modalities are necessary to establish preoperative confirmation diagnosis.10,11

Otosclerosis treatment is mainly surgical, through stapedotomy, whether partial or complete with the subsequent placement of stirrups prosthesis. In highly evolved cases, placing a cochlear implant is indicated.12

In this article we will assess the role of radiology in diagnosing otosclerosis, as well as its utility in diminishing surgical risk and in the diagnosis of postsurgical complications.

Radiographic findings. The role of the multidetector computed tomographyThe multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) is the modality of choice for the radiologic diagnosis of otosclerosis.4,11–15 Its sensitivity goes from 80 per cent to 95 per cent4,8,11,12,14,16,17 in the most recent studies, thanks to the technological improvements of these machines.

False negatives are due to foci smaller than 1mm and some lesions in sclerotic stages, their attenuation is similar to that of the normal adjacent bone.1,4,11,18

The preoperative MDCT allows us first to confirm diagnosis, by performing differential diagnosis with other conditions that also onset with conductive or mixed hearing losses, such as fixation of the non-otosclerotic ossicular chain, ossicular disconnection, superior semicircular canal dehiscence, dilated vestibular aqueduct, etc. It also allows us to identify factors of poor prognosis and anatomic abnormalities that can make surgery difficult, such as a dehiscent facial nerve or an obliterating footplate.

For its optimal characterization it is necessary to standardize image collection. Axial reconstructions perpendicular to the plane of the lateral semicircular canal are performed.

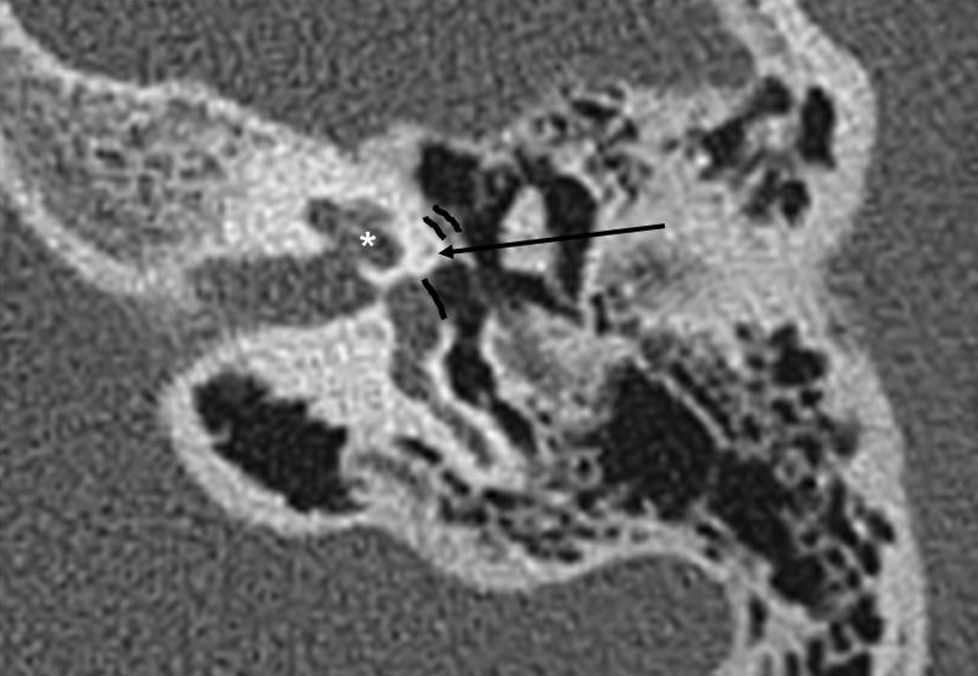

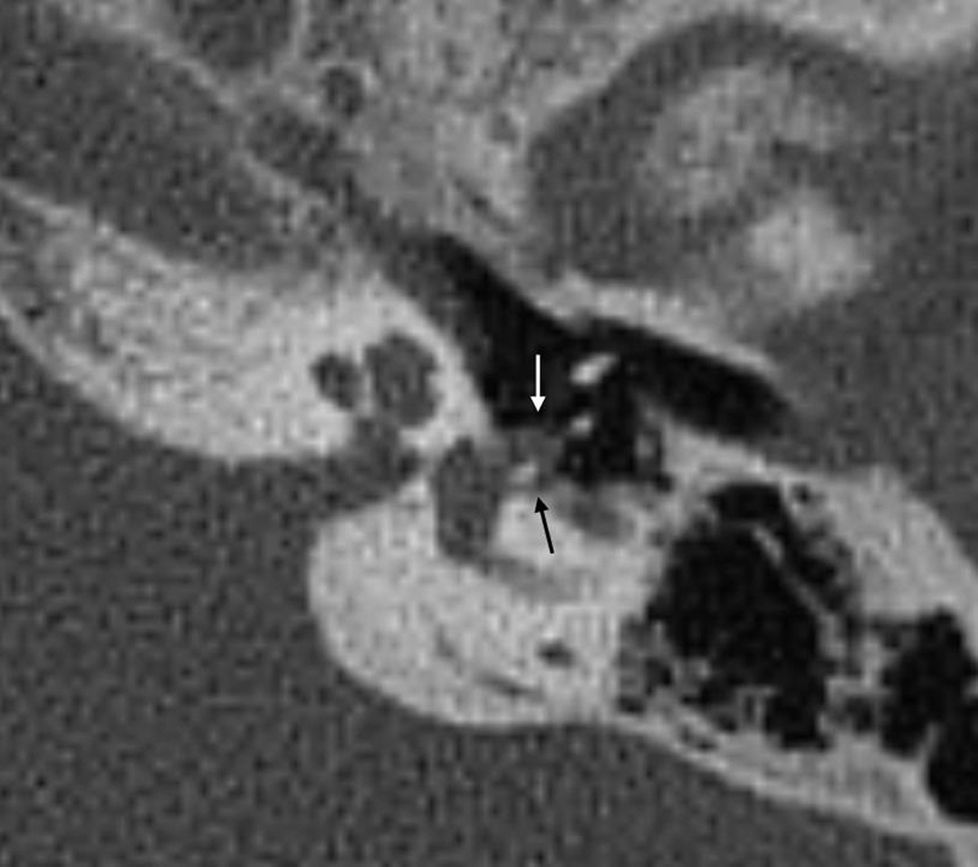

Axial slices are the most useful ones for the diagnosis of otosclerosis since the oval window, the fissula ante fenestram and the branches of the stirrup are better observed on this plane, and since the sensitivity for finding lesions is greater in fenestral forms13,14,19 (Fig. 1).

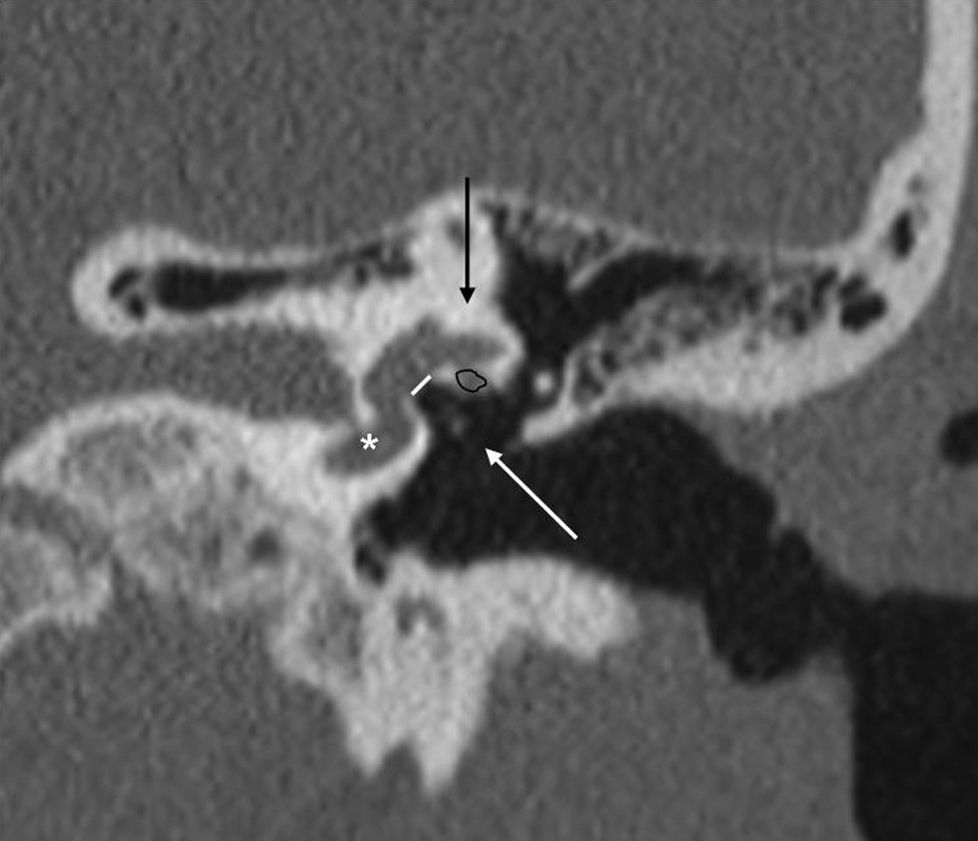

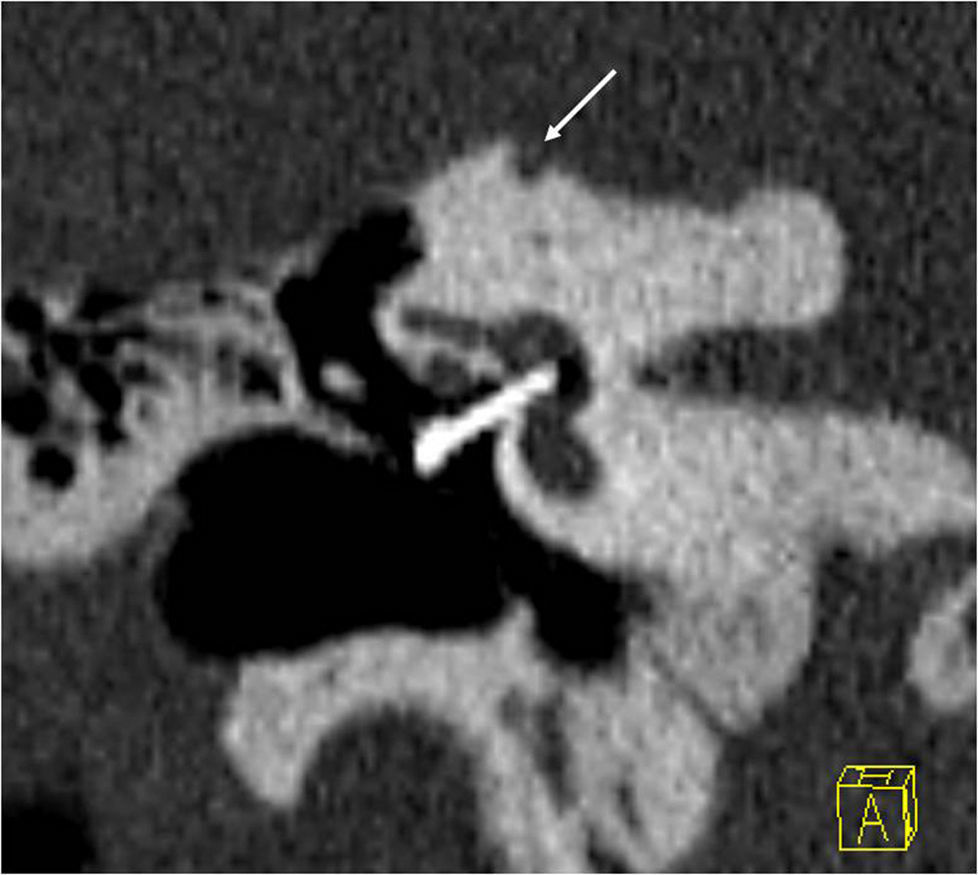

Coronal slices allow us to assess a possible dehiscence of the horizontal segment of the facial nerve, the height of the oval window, the thickness of the stirrup footplate or the presence of superior semicircular canal dehiscence (Fig. 2).

Radiographic findingsOtosclerosis is divided radiologically into two types: fenestral otosclerosis and cochlear otosclerosis. In general, cochlear forms encompass the fenestral form so at present it is considered that both are a continuum rather than independent forms.9,19

Fenestral otosclerosis70–80 per cent of fenestral otosclerosis cases are pure in form.8,14,20 They are characterized by otospongiosis, osteolytic lesions, in the fissula ante fenestram, the oval window, the round window, the facial nerve canal and the promontory.5,19 The most frequent location is the fissula ante fenestram, a cartilaginous fissure located just anterior to the oval window (Figs. 3 and 4).

The damage of the oval window determines the fixation of the stirrup that is the cause of conductive hearing loss.

The findings are subtle and the assessment of this area should be systematic in any CT scanning of the petrous bone. Bilateralism is 78–85 per cent.8,14 Bilateralism and symmetry of the findings make the comparison with the contralateral side often be of little utility for the radiologist inexperienced in its diagnosis.

Any osteolytic foci in the fissula ante fenestram is suspicious of otosclerosis.

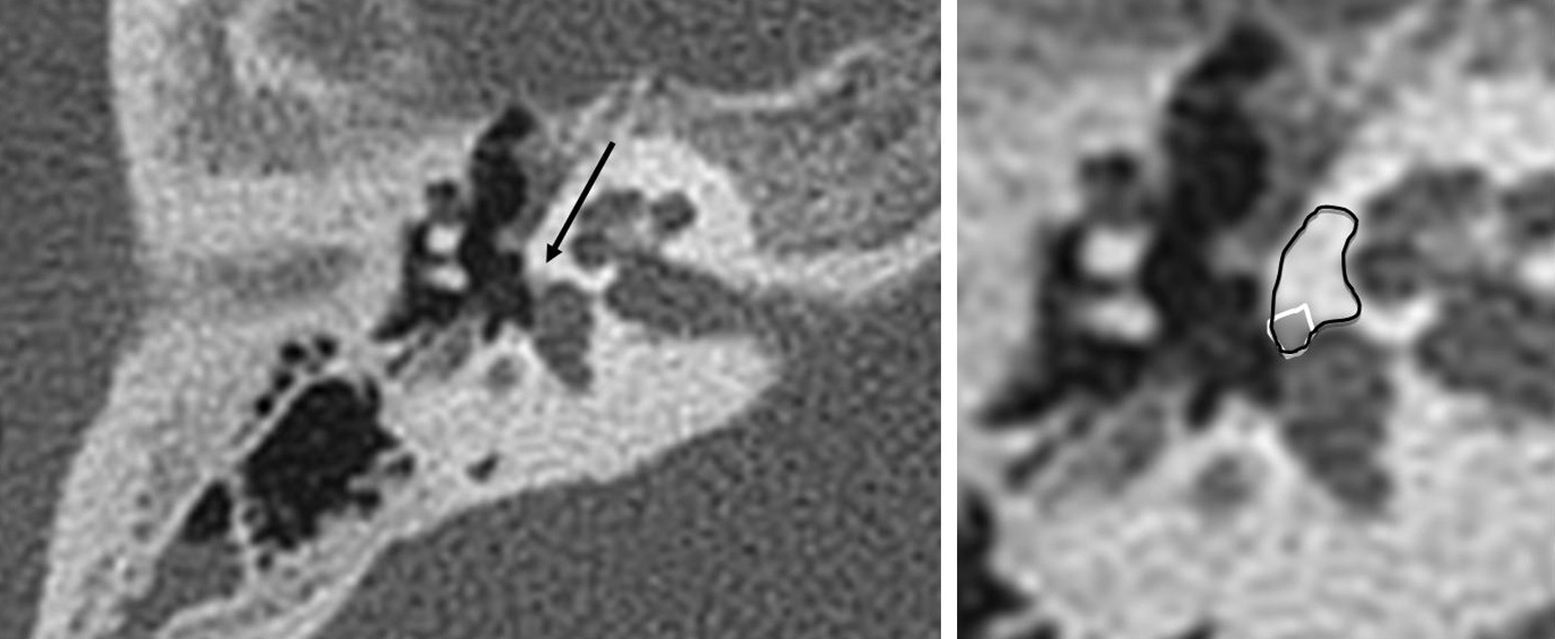

In 2 per cent of the cases, the occupation of the oval window is complete and then it is referred to as “obliterative otosclerosis”.1,15 Obliteration is the consequence of massive thickening of the stirrup footplate and the growth of the edges of the oval window that almost obliterate the niche or a combination of both1 (Fig. 5).

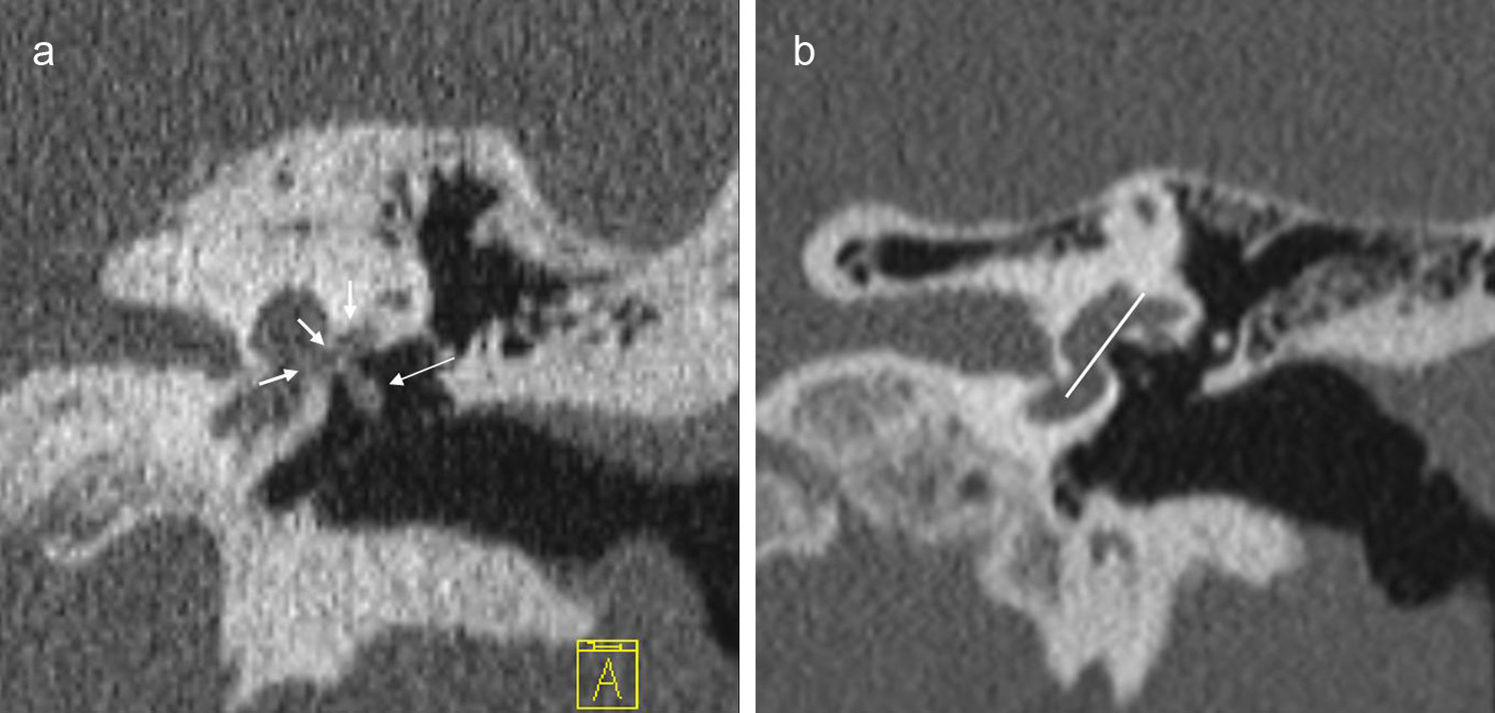

Obliterative otosclerosis. The figure shows a coronal slice at the height of the oval window (a). We can see the fenestral otosclerotic foci that obliterate the oval window (short, white arrows). The long, white arrow points at a marked thickening of the stirrup. The right image also shows the normal anatomy with the oval window plane (white line).

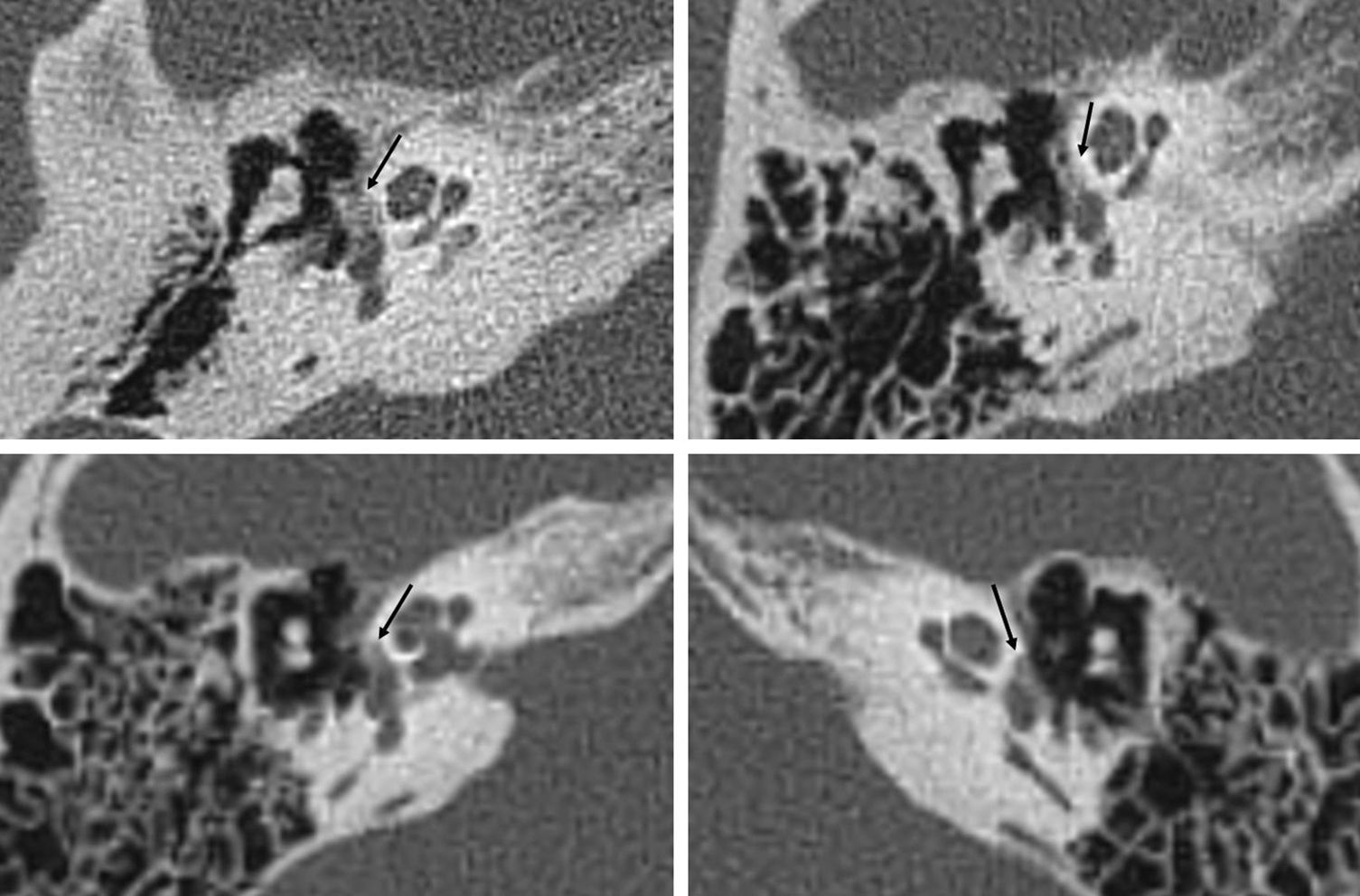

Less often, there is a diffuse thickening of the stirrup footplate as the only radiographic finding.1,4,14,19,20 Veillon et al.20 determined that stirrup footplate thickness in CTs is 0.48mm, and that values >0.6mm or irregularity >50 per cent of the length of the footplate are pathologic (Fig. 6).

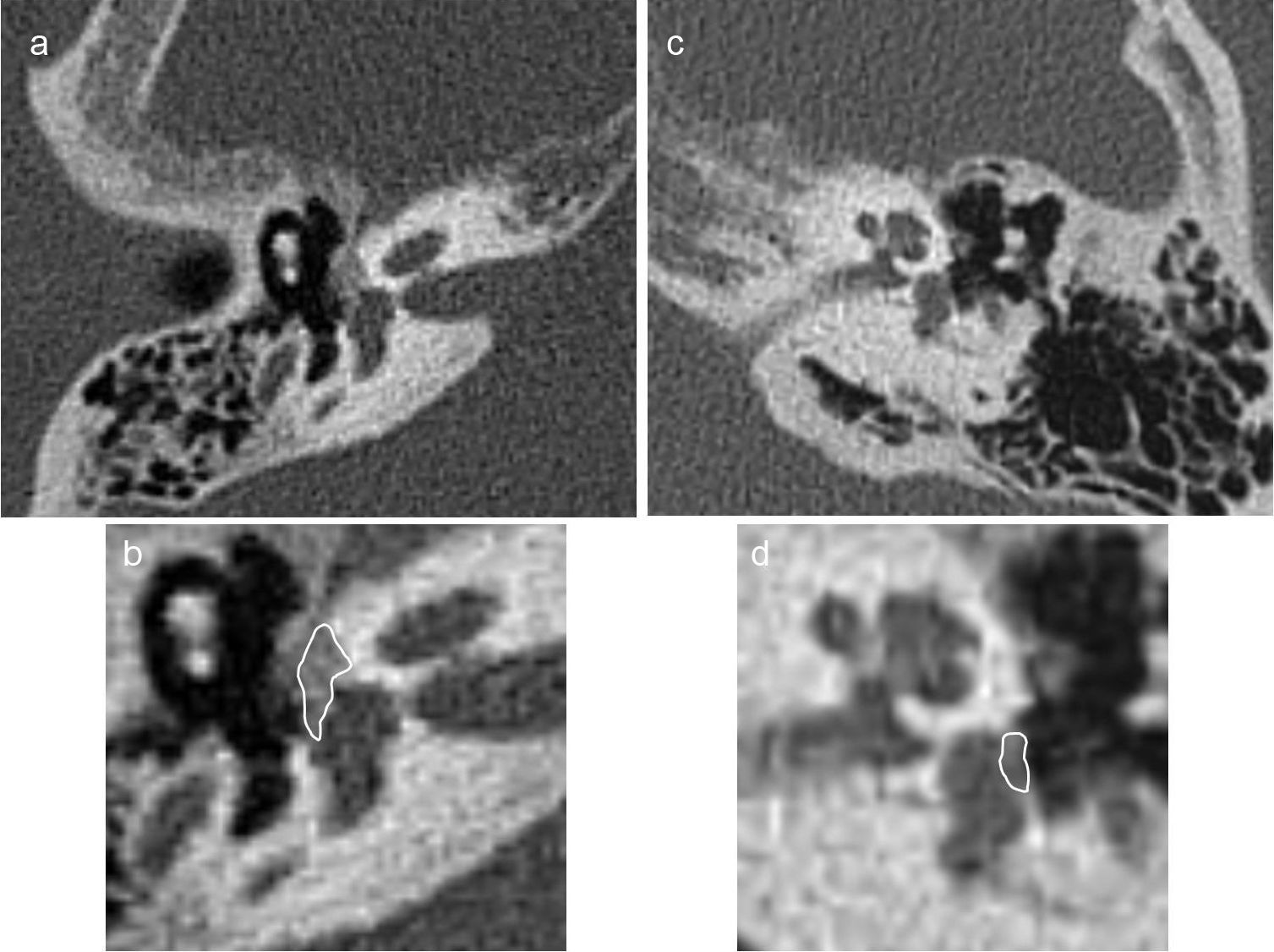

Fenestral otosclerosis with damage of the stirrup footplate in two different patients (a and b, c and d). We can see the fenestral otosclerosis focus in the typical location spreading toward the anterior oval window region (a); the blown-up image (b) shows the lesion edge in white. We can see the a subtle otosclerosis focus in the stirrup footplate (c); the zoomed-in image (d) shows the lesion edge.

Lagleyre et al.11 compared the MDCT preoperative findings with the surgical findings of patients operated on otosclerosis. Among the suspicious cases of otosclerosis in the MDCT, the focal thickening of the stirrup footplate anterior region and the thickening of the triangular morphology of the anterior branch of the stirrup were the most common ones (83 per cent), with a positive diagnosis in surgery in 94 per cent of suspicious cases.

The round window is affected in 7–10 per cent of the cases8,16 and it is generally included in fenestral forms.1,5,14,18,19 The sensitivity to detect foci in the round window is less for foci anterior to the oval window.11

Cochlear or retrofenestral otosclerosisIn a small amount of cases4 the disease evolves and the osteolytic foci spread along the otic capsule, reaching the promontory, the facial nerve canal, the cochlea and even the inner hearing canal. This type is known as cochlear or retrofenestral otosclerosis.

The fenestral form is present in almost all cochlear types.5,13,19 In our experience we have not found cases of isolated cochlear otosclerosis.

It ranges from very subtle otospongiosis foci to a marked demineralization of the pericochlear bone. A typical sign is the “pericochlear halo”18 (Fig. 7).

It is uncommon to observe otosclerotic foci adjacent to the inner hearing canal in CT studies, and they are generally associated with serious forms of cochlear damage.11

Patients with cochlear damage develop sensorineural hearing impairment, whose etiology is controversial. The most widely accepted theory associates inner ear damage with hyalinization of the cochlear spiral ligament secondary to the release of proteolytic enzymes from the otospongiosis foci located in the endosteum proximal to the ligament.1,21 CTs can find these foci though their absence does not rule out disease-related inner ear damage.

There are several CT classifications ranking the severity of otosclerosis. The work groups of Valvassori, Symons and Fanning, and Shin's, Rotteveel's and Veillon have established several classifications8,9,20,22–24 though none of them is widely accepted or predominantly used over the others. In clinical practice, the classifications are not widely used and it is necessary to determine their clinical utility if they change the treatment of patients and their predictive value prior to surgery.4,9

Differential diagnosisDifferential diagnosis of this disease is limited. It is important to know the patient's age. The presence of the cochlear cleft is very frequent in children a remnant of the embryonic fissula ante fenestram whose frequency decreases with age25 (Fig. 8): in children under four years of age it is >60 per cent and between 10 and 19 years its frequency is around 20 per cent.

False positives have been reported in the diagnosis of otosclerosis in cases of subtle radio-transparencies in the theoretical fissula ante fenestram correlated with areas of greater connective tissue and vessel presence17; thus the osteolytic foci anterior to the oval window are always suspicious of being associated with otosclerosis, but they are not pathognomonic.

Differential diagnosis is performed also with tympanosclerotic lesions in the middle ear, in which we can see diffuse thickening of the stirrup footplate similar to that present in otosclerosis. In general the attenuation of the footplate is greater in tympanosclerosis, and tympanosclerotic foci are usually more irregular.5 Findings of associated signs of chronic inflammation in the middle ear are frequent, as well as alterations in mastoid pneumatization and a medical history compatible in tympanosclerosis.

In much evolved phases of cochlear otosclerosis, the differential diagnosis with other conditions that demineralize the otic capsule, such as neurosyphilis, Paget's disease, fibrous dysplasia and imperfect osteogenesis, is practically impossible yet the clinical correlation is usually enough for its differentiation.18,19

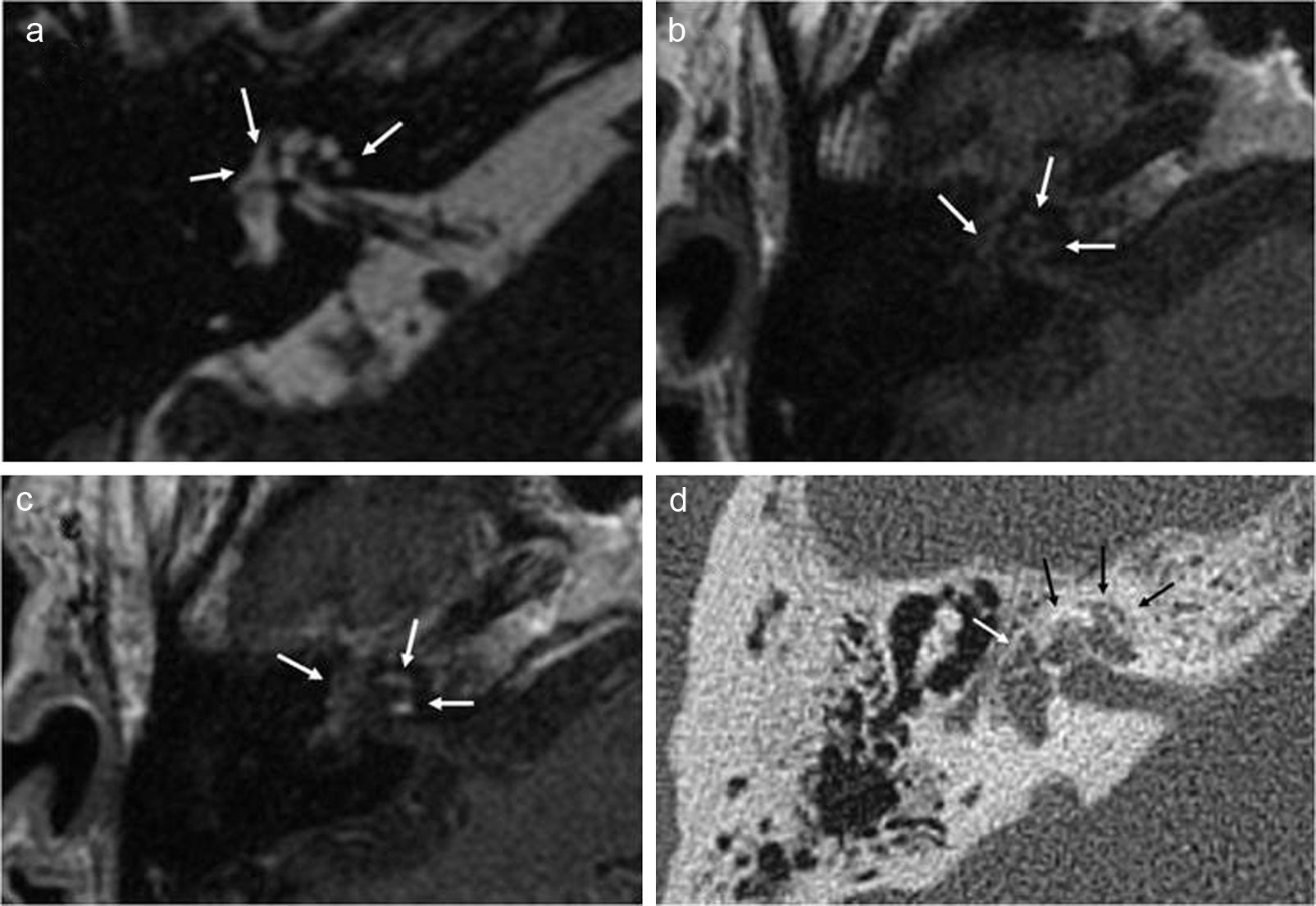

Diagnosis through other image modalitiesSometimes, the diagnosis of otosclerosis can be established or suggested through magnetic resonance images (MRI) performed for other reasons usually during the assessment of sensorineural hearing impairment. The MRIs shows a pericochlear halo of intermedial signal intensity in the T1-weighted sequences, with pericochlear enhancement in post-contrast sequences1,5,15,18,19,26 (Fig. 9).

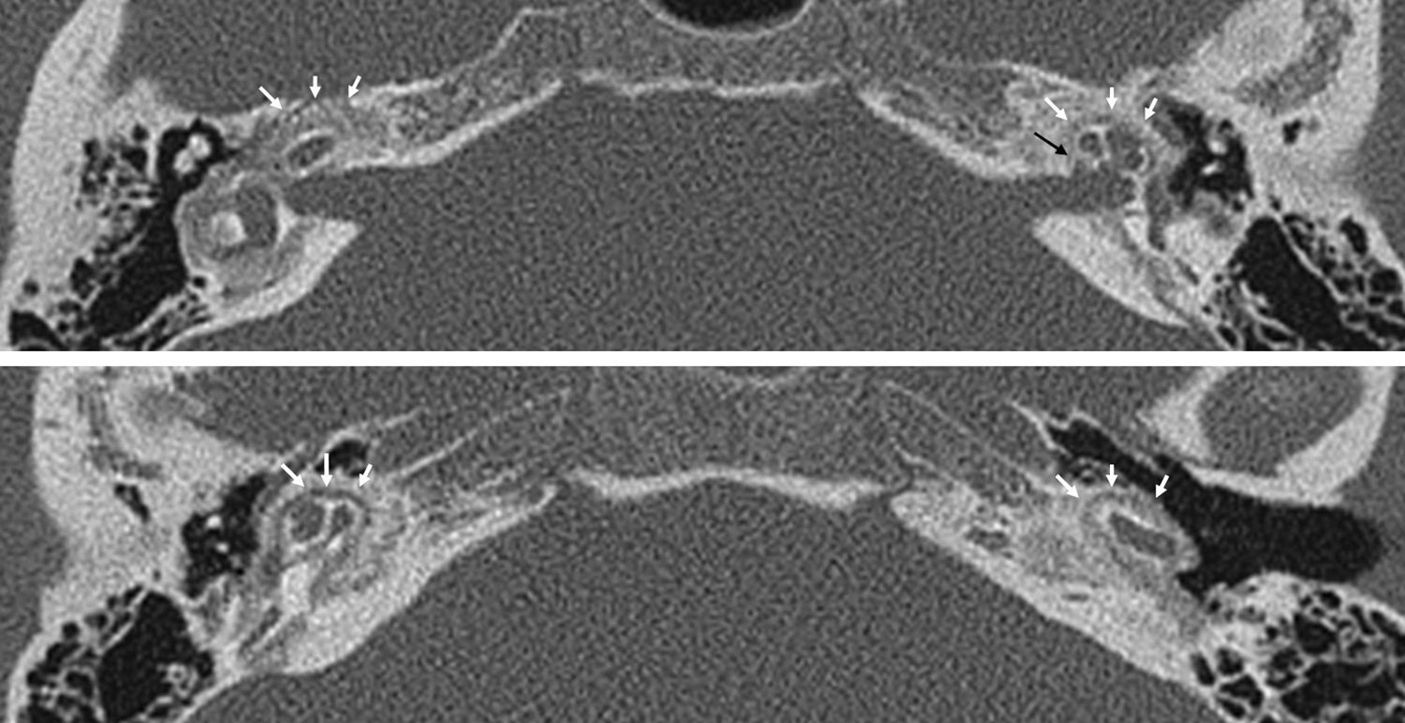

Incidental cochlear otosclerosis in an MRI performed on a patient with sensorineural hearing loss showing clinical manifestations and vestibular symptoms, without suspicion of otosclerosis. The image shows pericochlear and fenestral lesions (white arrows) in the FIESTA sequence (a) and the T1 axial sequence (b). T1 axial postcontrast sequence (c) shows pericochlear enhancement. The multidetector CT performed subsequently (d) confirmed the RM findings (white and black arrows).

It is believed that enhancement is due to contrast passage into numerous vessels in the otosclerotic foci18 and that it is associated with the activity of the disease.1 MRIs also allow us to diagnose possible lesions associated to the inner ear.

When thinking about performing a cochlear implantation the MRI allows us to assess cochlear patency,1,4,26 because though uncommon in cases of advanced otosclerosis there can be ossification of the basal turn that hampers or does not allow a correct insertion of the implant.

Several studies have been conducted assessing cone beam CT scans for the diagnosis16 of otosclerosis with promising results though its clinical utility is yet to be determined. Though its dose of radiation is smaller, its sensitivity to find fenestral forms is lower in cone beam CT scans than MDCTs.16

Systematic evaluation of postoperative CT scanning of the petrous boneCurrent evidence associates certain CT findings with an increased risk of intraoperative complications, as well as poor functional results and possible postoperative complications.

We must take into consideration:

- 1.

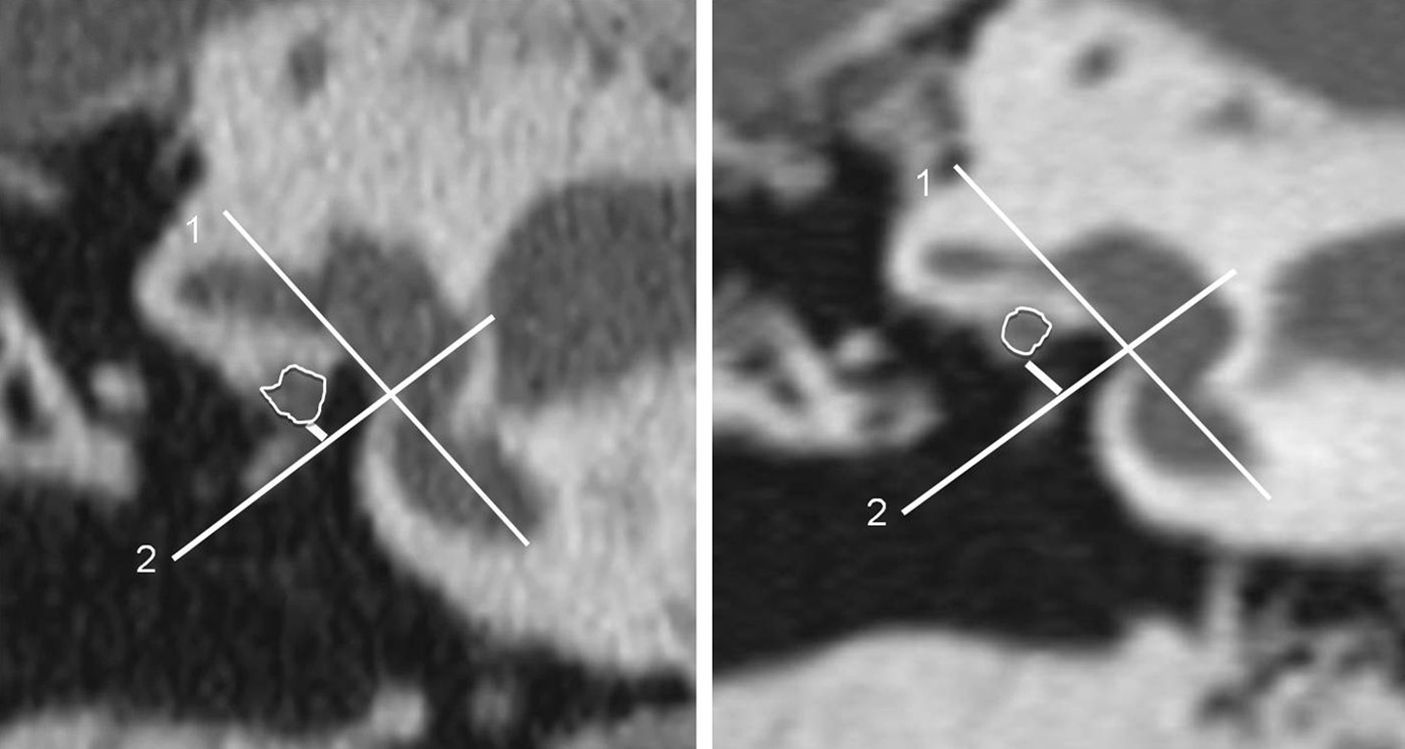

The size of the oval window niche: it can be reduced due to osseous hypertrophy of oval window walls, congenitally or secondary to the existence of otosclerotic foci, or due to prolapse or dehiscence or the facial nerve. Although trying to determine its size has been classically subjective, Ukkola-Pons et al.27 published an article in which they quantified the height of the oval window niche before surgery. They establish a value of 1.4mm as the lower limit of normalcy. Smaller values are associated with greater risk of technical difficulties during stirrup surgery (Fig. 10). Obliterative otosclerosis should be ruled out since this variant associates a greater risk of intraoperative complications and will require milling the footplate in order to place the prosthesis.

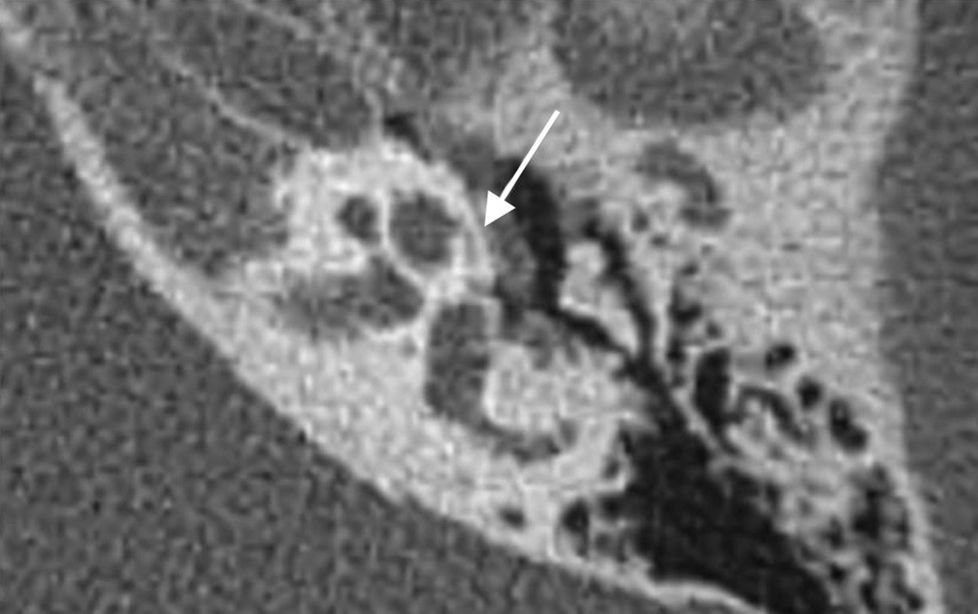

Figure 10.Estimate of oval window height. A plane parallel to the oval window and the larger vestibule axis is drawn (lines 1), and then a perpendicular axis is drawn at the height of the lower margin of the oval window (lines 2). Finally, a perpendicular line is drawn to line#2 up to the lower margin of the facial nerve in its horizontal segment (short, white lines). The image to the right corresponds to normal measurements. The image to the left shows a decrease of height compatible with a horizontal segment facial nerve dehiscence. The white edge outlines the horizontal segment of the facial nerve.

- 2.

The correlation between the facial nerve and the oval window: prolapse and dehiscence of the facial nerve are the second cause for a reduced oval window niche caliber. A dehiscent facial nerve can hamper or even make an stapedotomy or stapedectomy impossible. Its state needs to be systematically evaluated in all patients that will undergo otosclerosis surgery.

- 3.

The state of round window: it is important to explore it systematically since its affectation is associated with a greater risk of postsurgical sensorineural hearing loss.4,11,19,26 Round window obliteration though rare can be seen preoperatively and could contraindicate surgical treatment.19

- 4.

Lagleyre et al.11 find a greater risk of intraoperative complications in stirrup footplates in cases of suspicious or negative MDCT, probably because they are more superficial foci in which the stirrup shows greater mobility and the footplate is more fragile.11

- 5.

The extensive damage of the otic capsule and the inner hearing canal is associated with greater risk of postsurgical sensorineural hearing loss.4

- 6.

Rule out other causes for conductive, mixed or sensorineural hearing loss, such as dehiscence of the superior semicircular canal, congenital abnormalities or ossicular chain disconnection (chronic inflammatory condition of the middle ear or inner ear pathology, such as dilated vestibular aqueduct or ossifying labyrinthitis).5,19 The superior semicircular canal dehiscence is relatively frequent and it can occur with clinical manifestations similar to those of otosclerosis. It is an acknowledged cause of therapeutic failure in operated patients due to suspicion of otosclerosis. Its coexistence with otosclerosis is very rare.28,29

- 7.

Rule out the presence of a bulb of the inner high jugular vein that can hamper the surgical procedure.

- 8.

Assess the contralateral ear.

The value of MDCT is essential in postsurgical patients with a poor clinical evolution.30–33

The causes for therapeutic failure with persistence of conductive hearing impairment are:

- 1.

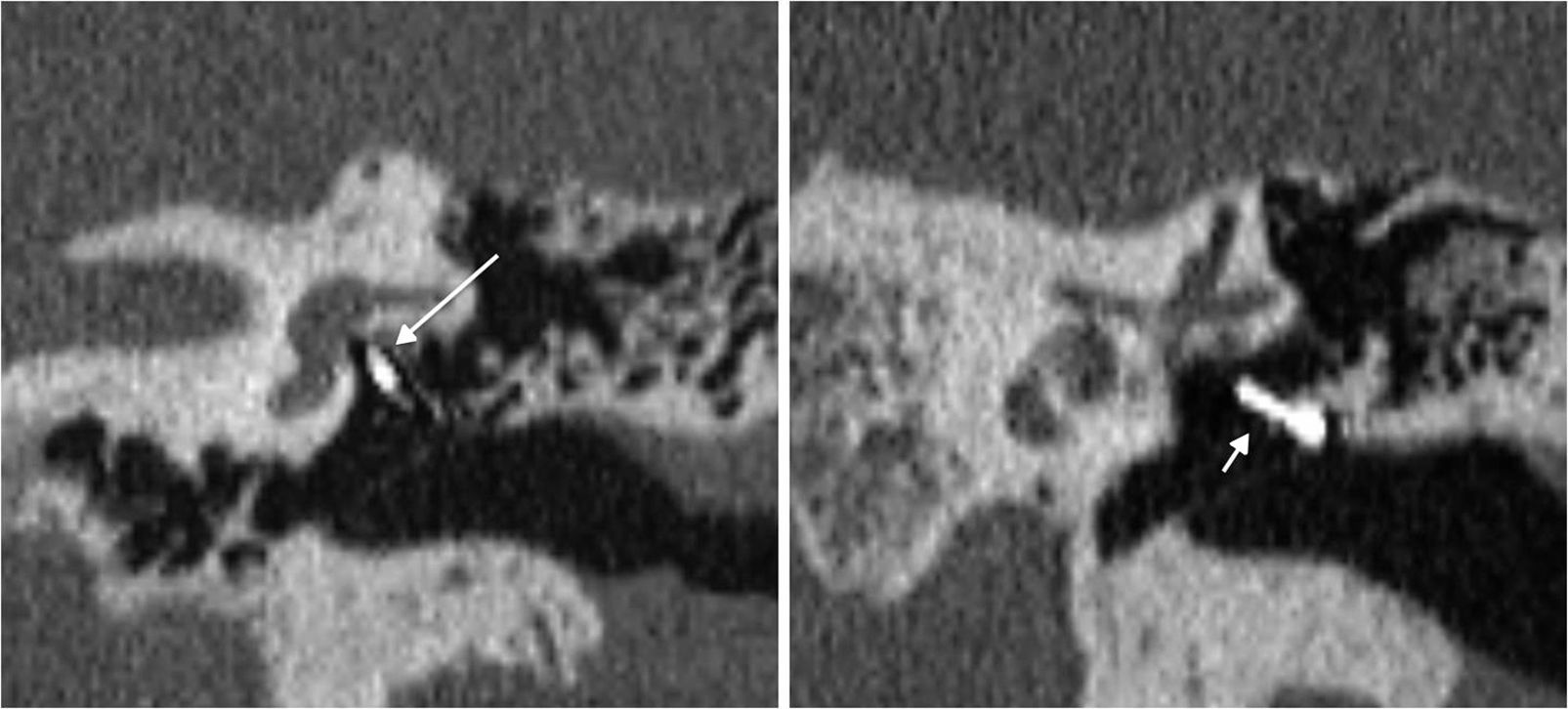

Prosthesis malposition with respect to the oval window fenestration: it is the most common cause of postsurgical therapeutic failure.30,34–36 The prosthesis must be medially, posteriorly and cranially oriented,30 and the tip of the prosthesis must be in contact with the oval window. Swartz19 considers that it is not necessary for the prosthesis to be in the center of the oval window; mild anterior or posterior displacements are considered normal. The most common occurrence is the displacement of the medial end of the prosthesis30,34; Williams et al.34 consider sub-millimetric displacements as pathologic. Disconnection, which is uncommon, implies the separation of the prosthesis with respect to the long apophysis bone of the anvil, and in this case luxation is usually very evident (Fig. 11).

- 2.

Necrosis with partial or complete anvil erosion especially the long apophysis of the anvil.30,35–37 Closely related with the displacement of the prosthesis its association is very common. Lesinski36 postulates that a displaced prosthesis fixates again on the residual footplate, that the medial end of the prosthesis continues to vibrate on the anvil thus conditioning its necrosis. It is described in up to 90 per cent of the cases of prosthesis displacement. Its diagnosis is common through surgery but it is difficult to find before hand through X-rays (Fig. 12). The first two causes represent 80 per cent of the total number of therapeutic failures.

Figure 12.Reconstructions on the oval window plane in a patient with bilateral metal stirrup prosthesis. In the left image we can see a millimetric separation compatible with a subtle necrosis of the lenticular apophysis of the anvil (white arrow). The image also shows an intravestibular protrusion of the prosthesis without any clinical repercussions (black arrow). The image on the right also shows the stirrup prosthesis in its normal position.

- 3.

Postsurgical fixation of the prosthesis or the chain of small bones due to granulation tissue (reparative granuloma) or adherences. A month after the surgery, there should not be any soft tissue increases in the oval window38 thus the presence of soft tissue increases adjacent to the tip of the prosthesis in the oval window will always be suspicious of reparative granuloma30,35,38 (Fig. 13).

- 4.

Progression of the disease, obliterative otosclerosis (uncommon).30,34,35 Otosclerotic foci obliterate again the footplate in a short period of time. CT shows an increase of soft tissues that is hyperdense in the oval window niche, adjacent to the medial edge of the prosthesis,30 with a reduced window caliber.

- 5.

Dislocation of the incudomalleolar joint.30,34,36

- 6.

Presurgical fixation of the malleus. It is usually found in the CT.

In case of appearance or progression of a sensorineural hearing impairment or vestibular symptoms, we should suspect the existence of a complication affecting the inner ear and thus consider performing a CT, an MRI or both30,31,39 but usually the initial modality is the CT scan.39

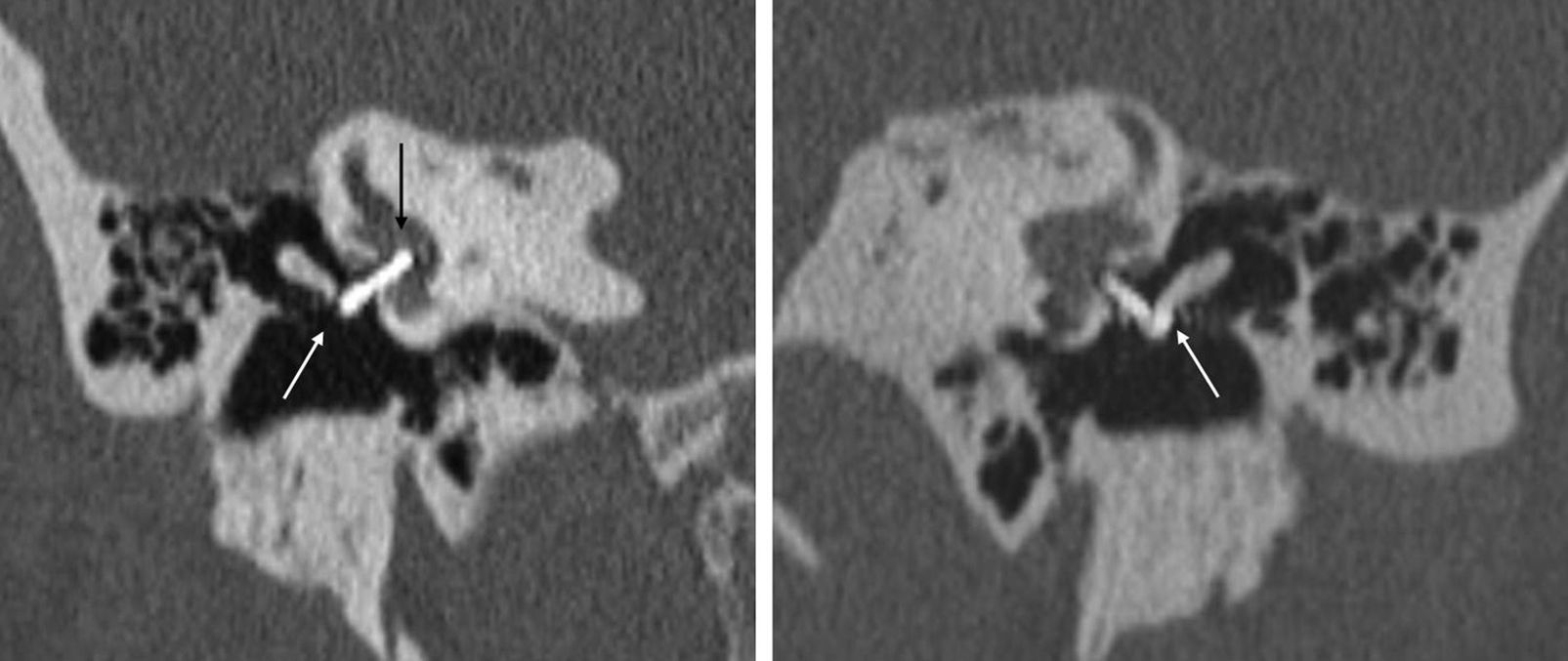

The utility of the CT scan in the assessment of intravestibular protrusion of the prosthesis has been described with different criteria. Williams and Ayache30 establish 1mm as the limit of the protrusion; Rangheard et al.,39 2mm; and Whetstone et al.,31 50 per cent of vestibule width. In the studies comparing CT images with anatomical slices,37,40,41 the fluoroplastic depth of the prosthesis tip in the vestibule is underestimated,37 while in metal prostheses it is overestimated variably in all the studies due to the artifact the metal material causes.1,37,40,41 The general conclusion is that the MDCT of up to 64 detectors does not allow us to assess correctly the intravestibular protrusion of stirrup prostheses40,41 (Fig. 14).

Perilymphatic fistula is suspicious if there is a hydro-aerial level in the middle ear, with air bubbles in the vestibule adjacent to the tip of the prosthesis.39

The MRI can evaluate the existence of intralabyrinthic hemorrhages, labyrinthitis, reparative granulomas in the oval window with intravestibular extension, perilymphatic fistula or malformations of the inner ear.30,39

In intralabyrinthic hemorrhages the inner ear structures show signal hyperintensity in T1- and T2-weighted sequences. Reparative granulomas show focal decrease of signal intensity in T2-weighted sequences, with enhancement in post-contrast sequences. The diagnosis of labyrinthitis is performed by confirming the occupation of the labyrinth by using enhancement in post-contrast sequences.

There is a great variety of compositions in stirrup prostheses. All of them are considered safe or of conditional use in MRIs,42,43 except the model 1987 McGee (Richards Company, Memphis, TN, USA)–already been withdrawn from the market.

ConclusionsThe MDCT is the modality of choice for the radiologic diagnosis of patients with otosclerosis and it allows us to perform differential diagnoses with other conditions of similar symptomatology. It provides us with prognostic information and allows us to identify cases with greater surgical risk. In the postoperative follow-up of complications either an MDCT or an MRI can be performed depending on the clinical suspicion we have.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments with human beings or animals have been performed while conducting this investigation.

Data confidentialityThe authors confirm that they have followed their center protocols on the publication of personal data from patients.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors confirm that in this article there are no data from patients.

Authors- 1.

Manager of the integrity of the study: JGM.

- 2.

Study Idea: JGM.

- 3.

Study Design: JGM, MM and NSG.

- 4.

Data Mining: JGM, MM, NSG, NA and MGB.

- 5.

Data Analysis and Interpretation: JGM and MM.

- 6.

Statistical Analysis: N/A.

- 7.

Reference: JGM, NSG and NA.

- 8.

Writing: JGM, MM, NSG and MGB.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant remarks: JGM, MM, NSG, NA and MGB.

- 10.

Approval of final version: JGM, MM, NSG, NA and MGB.

The authors declare no conflict of interests associated with this article whatsoever.

Please cite this article as: Gredilla Molinero J, Mancheño Losa M, Santamaría Guinea N, Arévalo Galeano N, Grande Bárez M. Actualización en el diagnóstico radiológico de la otosclerosis. Radiología. 2016;58:246–256.