On March 2, 1896, the local press in Malaga reported the discovery of X-rays, relating various news items about the use of X-rays and literature about Roentgen’s discovery by journalists and other authors. Outstanding among these writings was a periodical directed at the administration and general public called Los Rayos X. Progressively, the first X-ray machines were installed in hospitals during this period, and the first installation in a private medical clinic took place in 1900. In Malaga, the assimilation and progression of the diagnostic and therapeutic use of radiology was slow and affected by peculiarities owing to the social, economic, and cultural circumstances of the period. Influential physicians willing to overcome resistance to advances were able to bring medical practice in Malaga to a level similar to that of other cities.

El descubrimiento de los rayos X se conoció en Málaga el 2 de marzo de 1896 mediante la prensa local, que recoge además diversas noticias sobre el uso de los rayos X y evidencias del uso literario del descubrimiento de Roentgen por periodistas y escritores de esa época. Entre ellas, destaca la existencia de un periódico administrativo y de intereses generales denominado Los Rayos X. Los primeros equipos de rayos X se instalaron progresivamente en los hospitales de la época, y la primera instalación en un gabinete médico privado data de 1900. En Málaga, la asimilación y evolución del uso diagnóstico y terapéutico de la radiología fue lenta y con peculiaridades determinadas por las circunstancias sociales, económicas y culturales de la época. La presencia de médicos relevantes y con voluntad de superación consiguió elevar la práctica médica a un nivel similar al de otras ciudades de parecidas características.

Both scientifically and from a practical point of view, the discovery of X-rays was one of the most important events in the history of medicine.1 Addressing the view that we need to be aware of the history of the speciality, how technology has evolved, the lives of leading radiologists and radiology’s relationship with the “non-medical” world that surrounds it,2 our aim with this paper was to describe the introduction and development of diagnostic radiology, from Roentgen’s discovery until the 1940s, within the historical, health, economic and sociocultural context of Malaga.

Two sources of information about Malaga from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were particularly useful for this task. The first is the Archivo Díaz de Escovar, a public archive of Fundación Unicaja made up of the literature collection of Narciso Díaz de Escovar, writer, lawyer and journalist from Malaga, which has preserved virtually intact some of the newspapers from those years; available to consult online since 2002.3 The second is the Guías de Málaga [Malaga Guides] from those same years, spread around different archives and libraries across the city. Some data were also obtained, with permission, from document collections of the Official College of Physicians of Malaga.

The first news about the discovery of X-raysOver most of the nineteenth century, Malaga was a thriving city which enjoyed a huge economic boom thanks to its textile and steel industries, strong foreign trade and large agricultural production. Unfortunately, in the last quarter of the century a heavy economic depression along with several epidemic outbreaks (smallpox, trichinosis, cholera), the earthquakes of 1884 and 1885, the loss of the colonies and the wars with Morocco and the Philippines left the city in a state of ruin.4 The depression that brought the nineteenth century to a close continued into the early part of the twentieth century and affected all financial sectors and social classes.5

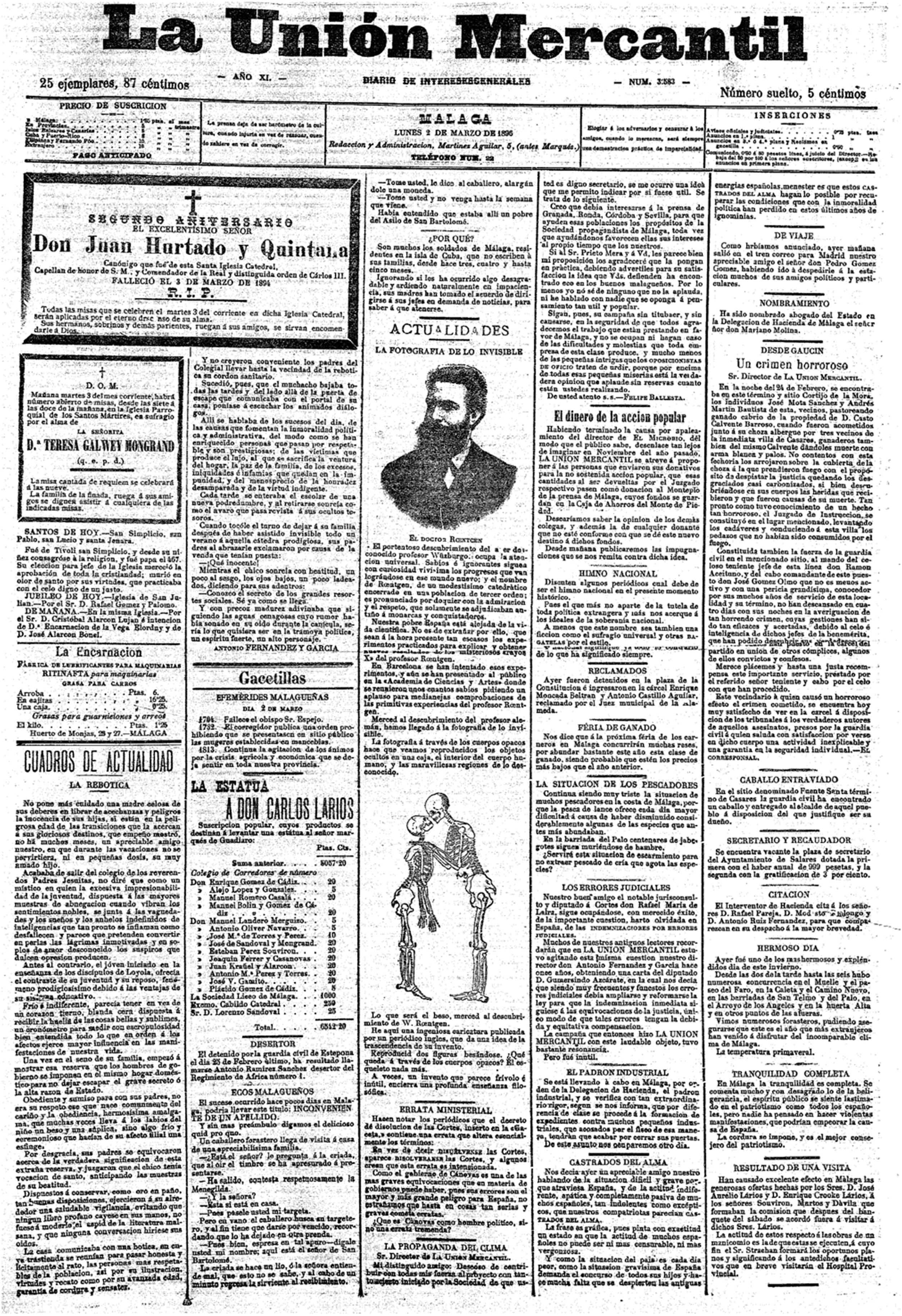

The people of Malaga learned about Roentgen’s discovery just four months later through the local press. The Malaga newspaper La Unión Mercantil of 2 March 18966 included a small article on its front page with the headline, “The photograph of the invisible” (Fig. 1) where, under an etching of Roentgen, it said,

“The portentous discovery of the teacher from Würzburg unknown until yesterday holds universal attention. The wise and ignorant are following with great curiosity the progress being made in that new world, and the name of Roentgen, a modest professor enclosed in a third-order population is pronounced everywhere with the admiration and respect that was once only awarded to monarchs and conquerors”.

The article continued stating that Spain lived cut off from scientific life, which explained the few experiments to date with the mysterious rays, although in Barcelona it had already been tried out and presented to the public (referring to the César Comas conference, during which the first public X-ray was performed in Spain, on 24 February 1896).7 The article concluded with the drawing of two skeletons kissing and some witty comments. Just a few days later, La Unión Mercantil8 announced that some members of the Sociedad de Ciencias Físicas y Naturales [Society of Physical and Natural Sciences] had met on 17 March in an unsuccessful attempt to reproduce Roentgen’s experiments. It seems that the demonstration of X-rays in Malaga was delayed, as no traces are found in the press of activity in this regard until May 1897, when it was announced that they were actively working to “shortly set up the necessary devices for the application of X-rays”.9 The announcement in the local press was later than other newspapers that reported the discovery in January 189610; for example: El Liberal published its article under the headline “Strange discovery”, La Correspondencia de España, a Madrid paper, published another with the headline “Monumental discovery”, El Eco de Navarra used the headline “A sensational discovery”, El Guadalete, in Jerez de la Frontera, also had “Monumental discovery” and La Vanguardia, had the headline “Dr Röntgen’s discovery”.11 Some illustrated magazines were even brought forward, such as La Ilustración Artística, with the article, “Roentgen’s Rays”,12 and La Ilustración Española y Americana which in January also published an article by Dr Ricardo Becerro de Bengoa entitled “Dr Röntgen’s X light”,13 and days later another by Antonio Espina y Capo called “Radiography or the study of Dr Roentgen’s X-rays”.14 In 1897, the Malaga press reported several advances of the discovery in the world, such as the article entitled “X-rays in customs. Adoption of X-rays by the French customs authorities”,15 where they explained the application of X-ray to examine the baggage at customs at three major rail lines in Paris.

From 1898 on, civilian and military hospitals across Spain gradually began to be equipped with X-ray equipment.16 The first X-ray devices were installed in health centres in Malaga, such as the Hospital Civil Provincial (built in 1867), considered the most important hospital in Malaga until the mid-twentieth century, Hospital Militar (1836) and Hospital Noble (1861). Although we cannot be certain of exactly where and when X-ray equipment was installed, some information is available in the local press. In September 1898, the photographer Ramón Giménez Cuenca Bonilla informed the then president of the Red Cross in Malaga, Dr Lorenzo Cendra, that he had installed a department at Hospital Civil to aid the wounded from Cuba, while he offered, “his all-important services as radiographer teacher for the hospital”.17 Medina Domenech et al.18 claimed that Dr Martín Gil, director of Hospital Noble de Málaga, began to use X-rays in the city for diagnostic purposes in 1898. Coinciding with that timeline, the local press reported that the hospital underwent substantial renovations that year.19,20 Then in 1907 there is evidence that an “excellent X-ray facility” was donated to Hospital Noble.21 We do not know when they started using X-rays at Hospital Militar, but the “Radiography” section of an inventory of healthcare materials from 1911 records “two Roentgen tubes, four photograph presses, one fluorescent screen…”.22

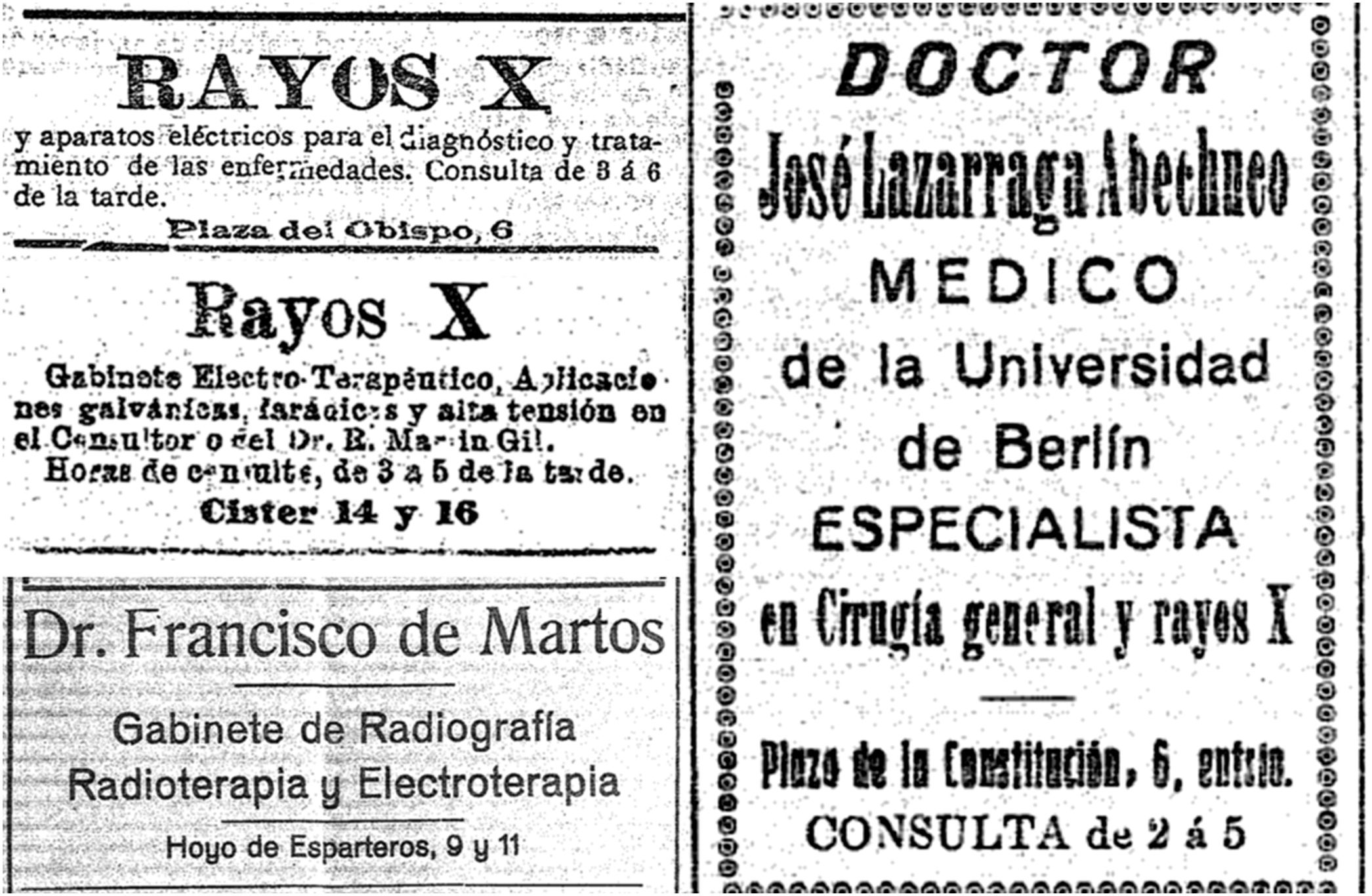

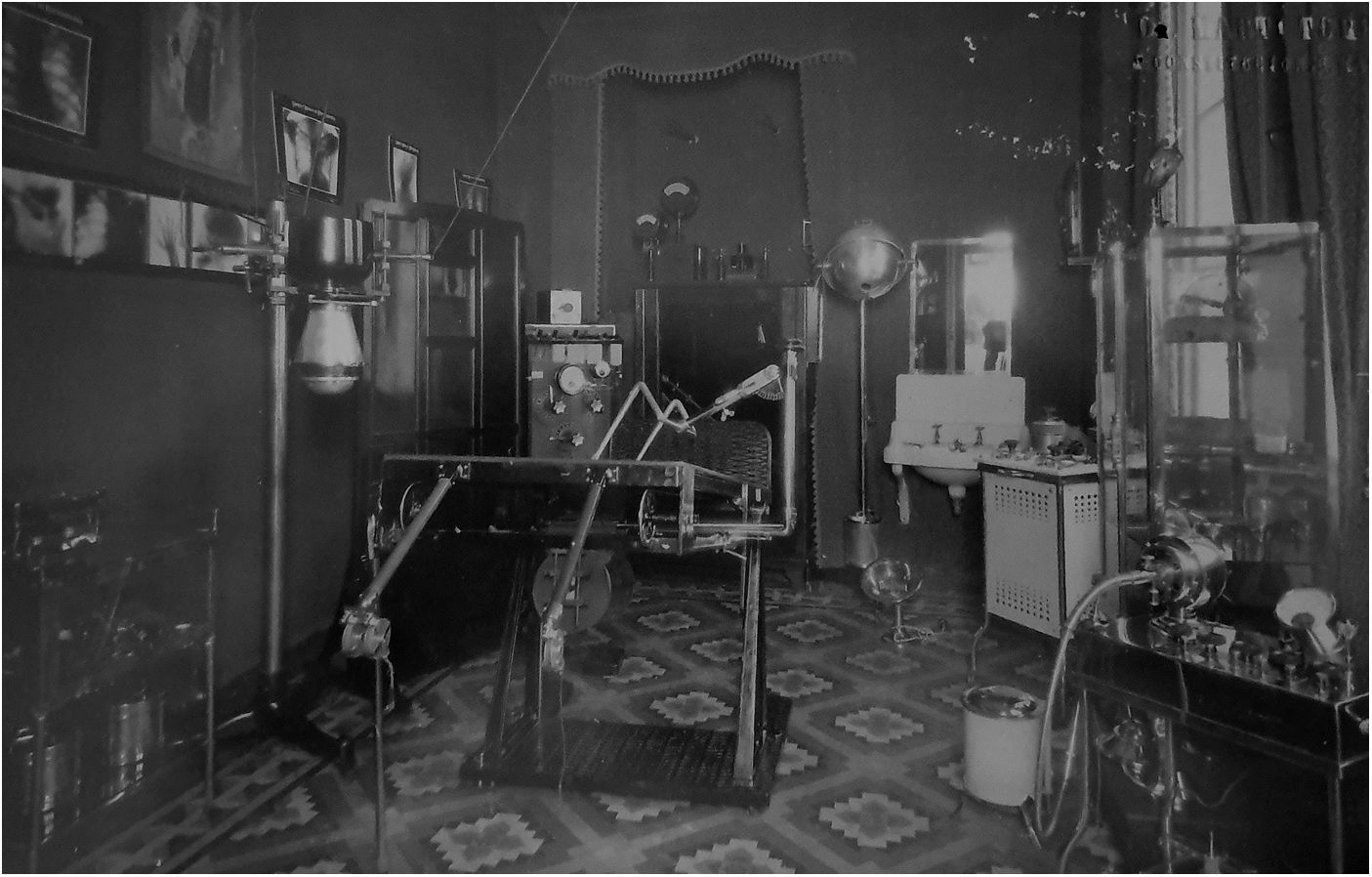

Pioneers in the use of X-rays in MalagaIt is not until September 1900 that we find an announcement in the press of the first private diagnostic and therapeutic electroradiology clinic23 at Plaza del Obispo, No. 6, the offices of Dr Ramón Martín Gil (1853-1916) who, four years later moved both his home and clinic to Calle Cister14-1624 (Fig. 2). This famous Malaga doctor was known for his expertise as a surgeon and his desire to investigate and innovate, which led him to test and use the first radiology devices at Hospital Noble and at his private clinic. He held a distinguished position in the Academy of Medicine and Surgery of Barcelona and later in the Academy of Madrid.

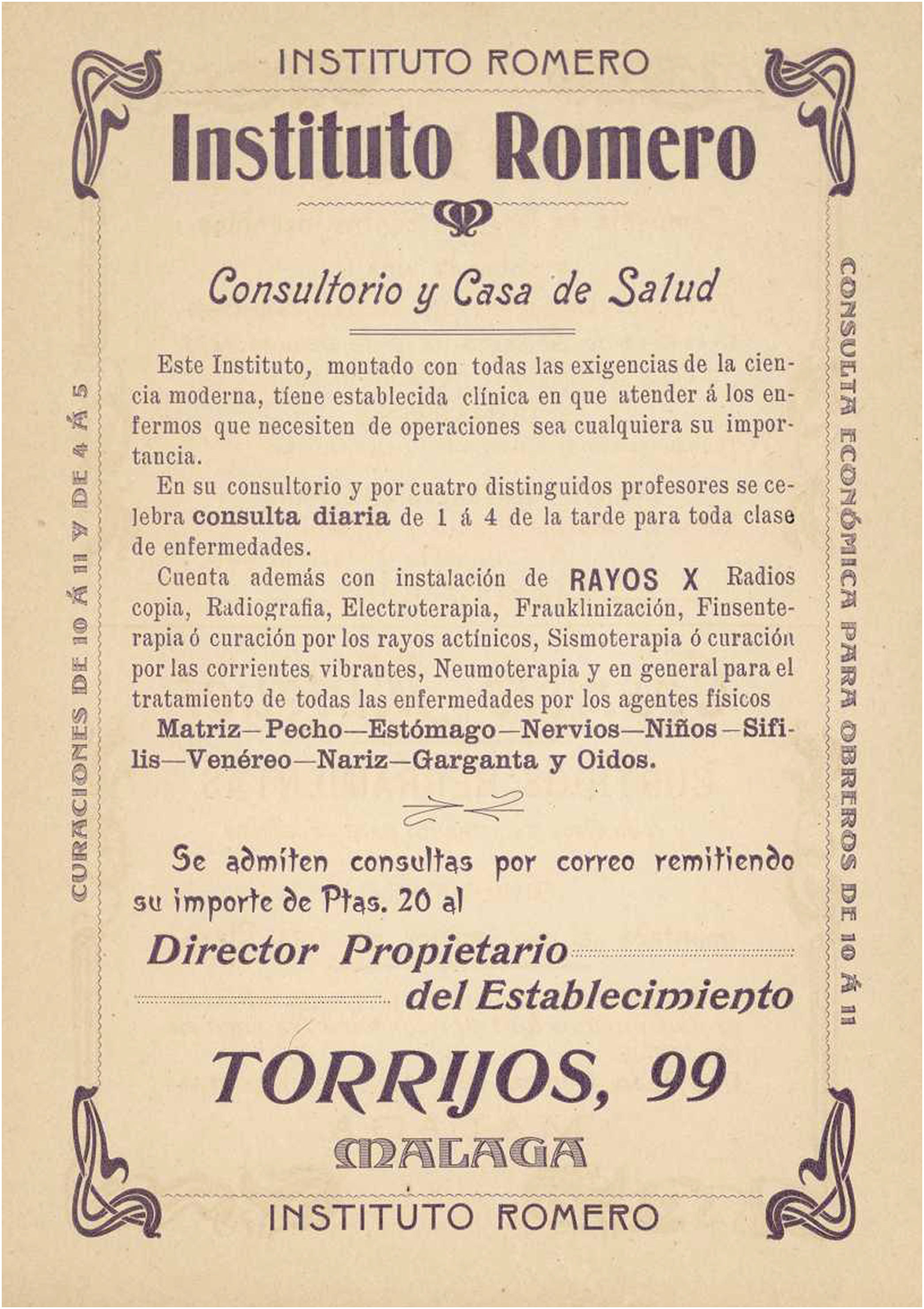

As the economic recovery began to take hold in Malaga, new clinics run by renowned specialists in other fields gradually started to appear with X-ray equipment added to their range of instruments. Advertisements of “X-ray Clinics” such as Instituto Romero, appear in the Guías de Málaga for 1905 (Fig. 3).25 For the whole of May 1912, La Unión Mercantil ran the advert for a new radiology, radiotherapy and electrotherapy clinic, run by Dr Francisco de Martos (Fig. 2)26, physician and surgeon who practised at Hospital Civil. In November 1914, an advert appeared about the clinic opened by Dr José Lazárraga Abechuco27 who, in addition to being a surgeon, also advertised himself as an “X-ray specialist”, having obtained both qualifications from the University of Berlin (Fig. 2). This was the first time this qualification was publicly used among doctors in Malaga. Dr Lazárraga Abechuco was twice president of the Official College of Physicians of Malaga, director of the Maritime Sanatorium of Torremolinos and professor of surgery at Hospital Civil.

A literary view of X-raysThe discovery of X-rays had a big impact on the media and the imagination of the time. The literary style of the journalists of back then echoed that impact. The first news about Roentgen’s discovery in La Unión Mercantil was given the headline “The photograph of the invisible”,6 a literary expression which was used on more than one occasion to refer to X-rays,28,29 and concluded with a philosophical reflection on what remains of the human being to see through opaque bodies. X-rays even became a normal part of popular language and jokes were made about their possibilities; only a few days later, La Unión Mercantil placed30 a short feature on their front page entitled “Crónica Malagueña” (Malaga Chronicle) saying, “When you annoyed them, the rougher elements of Malaga society used to say, ‘Hope you get struck by (a ray of) lightning’. Now the more educated parody that violent expression, making it more scientific, ‘Hope you get lit up by a ray (of lightning)’, alluding, the reader will have understood, to the Roentgen rays, the applications of the cathode light…” “… Well, and the anatomical portraits achieved with this process? In Malaga they would help answer a lot of questions. It would be interesting to see the insides of certain councillors; the stomach of a famous chieftain, the tongue of a local speaker no less famous; the guts of some, that’s if they have them, must be very bad, and the entrails of those who treat Malaga as if it were a conquered country. If the application of X-rays becomes widespread, I advise that no member of parliament or councillor be chosen without first SEEING THEM FROM THE INSIDE”.

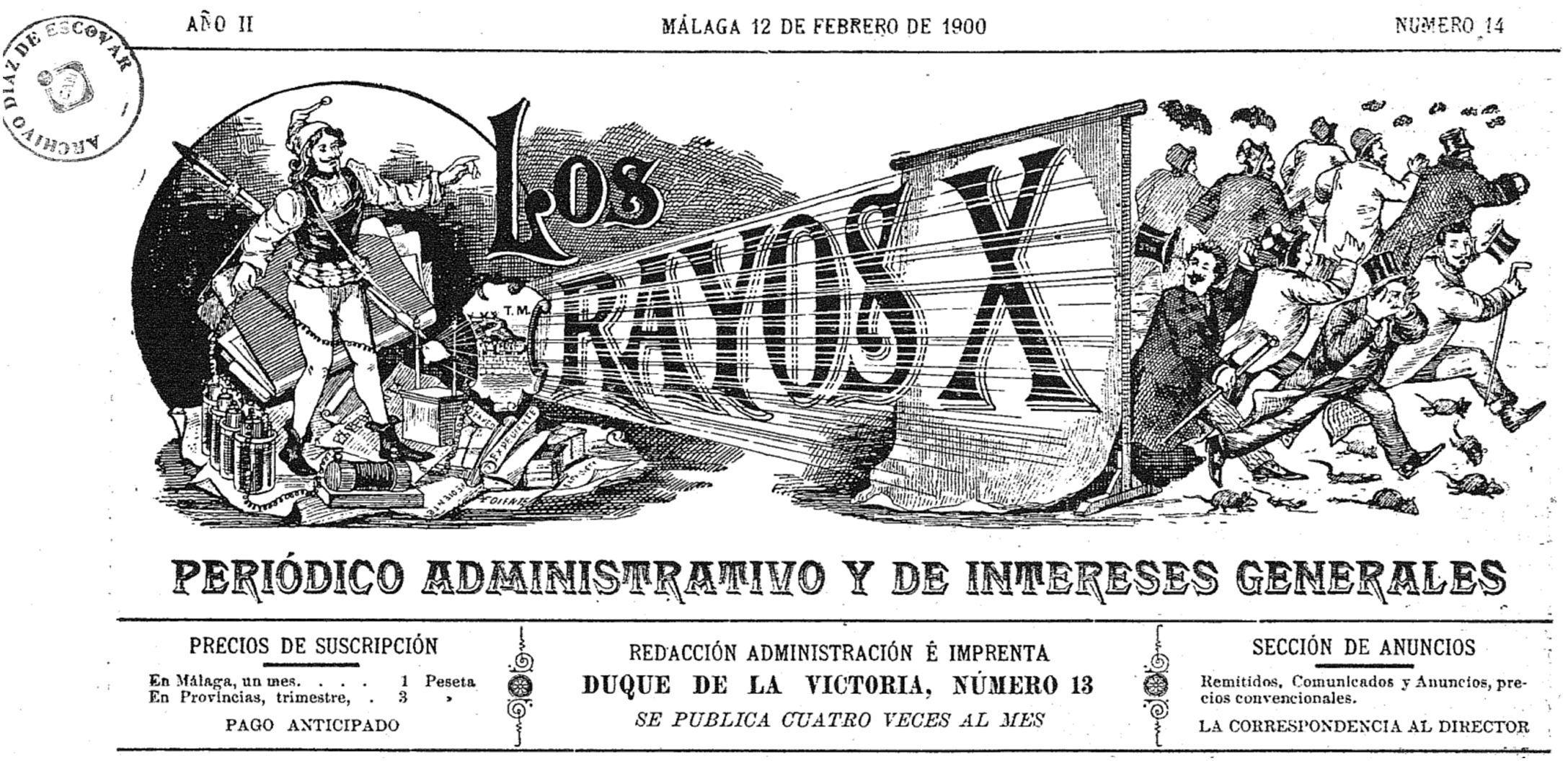

Among the local publications of the late nineteenth century, one administrative, scientific and general interest newspaper stands out due to its very title, Los Rayos X (The X-rays). It was first published in October 1899 and three copies are kept in the Díaz de Escovar Archive. The title of this publication is a literary simile of the radiation discovered by Roentgen to look through society and analyse it, which some expressions perfectly reflect, “…using the invisible light to analyse with full clarity ‘opaque’ situations in municipal life”. Issue No. 3 of 8 November 1899,31 the first available (Fig. 4), includes a report on the refusal of some mansion owners to pay taxes, the reference to a municipal crisis, threatening to reveal a secret or a list of debtors to the City Council. The second preserved issue is from 1 December 1899.32 It includes a short feature, entitled “From the device”, full of ingenious radiological technicalities: “In our desire to inform the public and so find out what really is through these opaque bodies that are most typically referred to as ‘local reform project’, we have obtained different projections, the result of which, in order, is as follows…”

This paper continued to be published for several years. The leading story in the last issue preserved, that of 12 February 1900,33 shows a spectacular illustration (Fig. 5) in which a character, representing a journalist, operates an X-ray tube from which a beam of rays emanates. Through the shield of the city, this beam is projected onto a screen behind which flee terrified characters wearing top hats, representing the upper class of society, along with rats and bats. To our knowledge, the weekly Los Rayos X [X-rays] is one of the first examples of using Roentgen’s discovery to provide a detailed description or analysis of something not very transparent. This figurative use became popular and lasts to this day. The Real Academia Española [Royal Spanish Academy] (www.rae.es), whose aim is to ensure the stability of the Spanish language, gives three definitions of the term X-ray, with the third clearly in this context: “f. Detailed description or analysis. An excellent social X-ray of the time”.

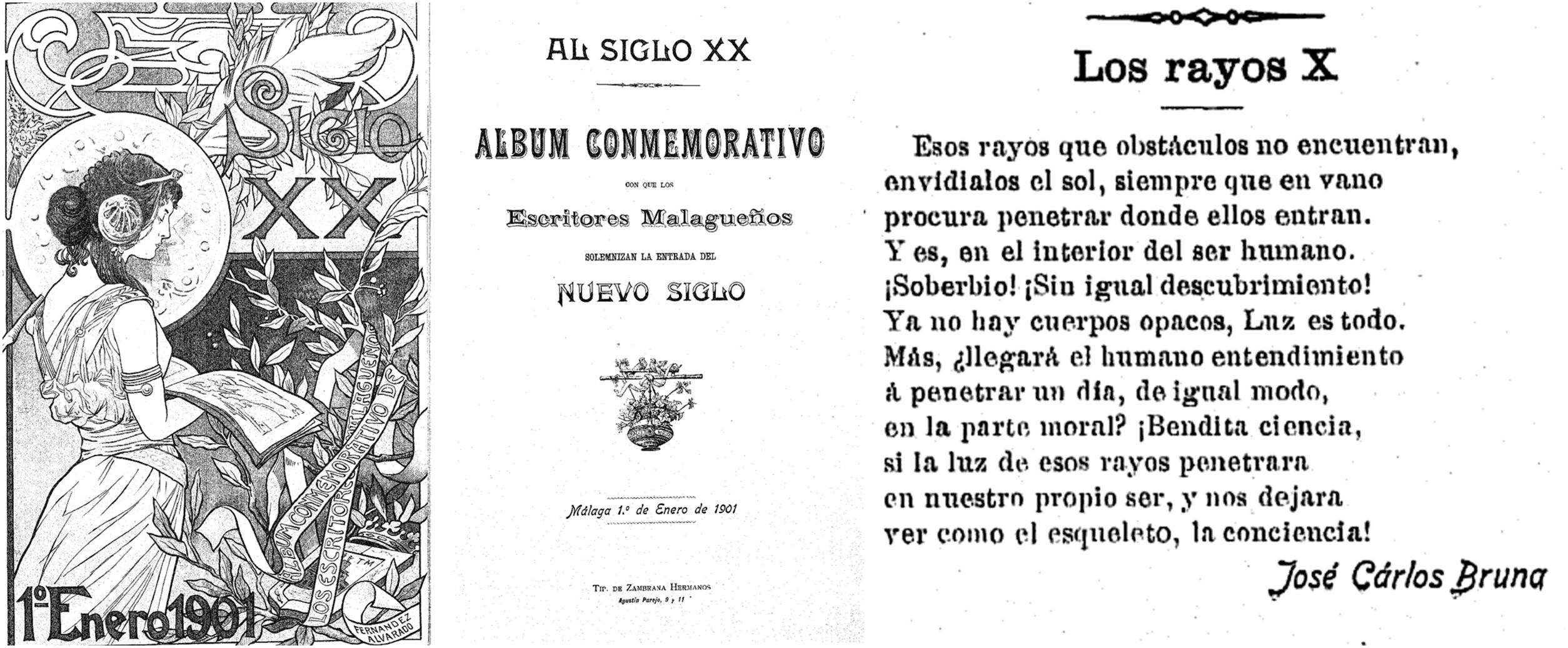

Another interesting example of the literary use of X-rays is found in the poem by the renowned Malaga journalist and writer José Carlos Bruna, entitled “To X-rays”, published in 1901 in the journal Al siglo XX34 [To the 20th Century], in which the author expresses his wish that someday science will let us see less tangible aspects of the human being, such as the moral or the conscience (Fig. 6).

The 1920s and 30sFrom the mid-1920s, Malaga saw a slight resurgence in its economy, marred by the terrible events that ravaged the life of the country in the thirties, culminating in the Civil War. The Chorro dam was built during this time, through a company formed by prominent members of the local oligarchy, and this meant a turning point in Malaga’s electricity supply, which up till then had been obtained from small steam or hydroelectric plants.35 From May 1921 to 1936, Malaga’s Official College of Physicians published the journal Revista Médica de Málaga [Medical Journal of Malaga], and it can still be consulted virtually in full at the College’s library.

The public health infrastructure in Malaga went from a charity-based system to a secular government-based benevolent system that considered medical care as a basic right for human dignity.36 The existing Hospital Civil, Hospital Noble and Hospital Militar were acquiring new radiodiagnosis and radiotherapy equipment for their facilities. Radiology was also being practised over this period in the private sanatorium of Dr Gálvez Ginachero, gynaecologist and director of Hospital Civil, and in private clinics dedicated to other specialities.

There are records of four doctors who practised radiology during this period: Drs Cristóbal Porcuna García, Jerónimo Forteza Marti, Antonio Luna Arjona and Manuel Marti Torres. Only the last two were in the General Archive of the Official College of Physicians of Malaga with the speciality of electroradiologist. These first specialists from Malaga acquired their knowledge and specific qualification at national universities (especially Madrid, Barcelona and Seville) and abroad (France and Germany in particular). They, in turn, passed on their knowledge to Malaga doctors through conferences in the city’s different forums and in the articles they wrote, translated or summarised for the Revista Médica de Málaga.37

Dr Cristóbal Porcuna García (1890–1970), specialist in gynaecology, was in charge of the radiology department at Hospital Noble for a few years.37 Dr Jerónimo Forteza Marti (1882–1953), military doctor and paediatric specialist, worked at Hospital Militar as director and as radiologist. He set up a radiological clinic at No. 4 Alameda Principal and was a member of the board of directors of the College of Physicians and the Athenaeum of Medical Sciences of Malaga. In 1927 and 1928, he published two articles in the journal Revista Médica de Málaga: “Clinical value of chest X-rays. Rules of interpretation” and “Abnormal shadows on the chest X-ray”.37

Dr Antonio de Luna Arjona (1899–1989) specialised in surgery and electroradiology and became a member of the College in Malaga in 1924. In 1927, he obtained the surgery position at Hospital Civil, whose director, José Gálvez Ginachero, put him in charge of the electroradiology equipment. He also practised as electroradiologist specialist for the Malaga Red Cross.38 He was a member of the governing board of the Official College of Physicians until after the civil war.37 He collaborated with the editorial committee of the Revista Médica de Málaga, where he published many articles, including “X-ray Atlas”, a collection of X-rays with footnotes published in several consecutive issues. He had a radiology/surgery clinic on Calle Sánchez Pastor, also used by his son, Dr Luna Ximénez de Enciso, who kept it on until the 1990s.

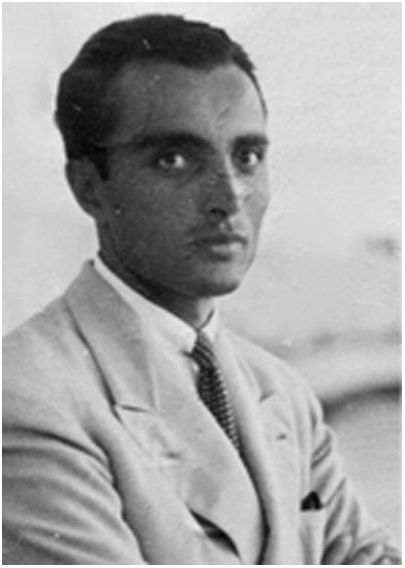

Dr Manuel Marti Torres (Fig. 7) was without doubt Malaga’s best known radiologist of the 1920s. He was also a qualified specialist in dentistry. He arrived in Malaga in 1921, after finishing his undergraduate and doctoral studies at the University of Granada, and set up his clinic in Plaza de la Constitución (Fig. 8). He gave numerous lectures and wrote many articles on radiodiagnosis, radiotherapy and even history, such as “The Death of Bergonié”, one of the most illustrious teachers of French electroradiology, who died victim of the action of X-rays.39 He wrote a book with Dr Bentabol Jiménez, entitled “Imágenes fundamentales y lectura radiológica en tuberculosis pulmonar”40 [Basic images and X-ray reading in pulmonary tuberculosis], aimed at general practitioners who were starting out in both radiology and in phthisiology. He was a highly renowned physician, both locally and nationally. He was part of the Board of Directors of the Athenaeum of Medical Sciences of Malaga and was elected 4th member of the Sociedad Española de Electrorradiología Médica (SEREM) [Spanish Society of Medical Electroradiology], on the Board of Directors chaired by Emilio Larru Fernández.41 First member of a dynasty of radiologists from Malaga who continued his work, he was succeeded by his son Dr Pablo Marti Martínez and then Dr María Dolores Marti Crooke, who still runs the radiological clinic founded by her grandfather.

The 1940sOne of the main themes of these post-war years was the lack of essential goods. Supplying of the whole country suffered a period of serious difficulties, with ration cards introduced to try to guarantee minimum provisions to the Spanish population.35 Rationing of electricity use and the shortage of plates were two great problems affecting radiology in Malaga. In 1949, Dr Marti Torres wrote to the Official College of Physicians reporting that the electric current reached 130 volts but that the X-ray and electrotherapy devices needed 220 volts to operate, and requesting that the Delegation of Industry rectify this deficiency. The College agreed to ask the Chief Engineer to give doctors who had X-rays an hour of electricity from 6 to 7 in the evening, in addition to the existing supplies from 12 to 2 p.m., considering it “of much interest to the sick population”.

In February 1940, the City Managers approved a motion which reorganised the Specialist Services at Hospital Civil Provincial, creating the department of electroradiology, separating it from the surgery department.38 Not long after, in 1943, the position of head of department was announced and was filled by Dr Rodrigo Domínguez Estévez, at which point Dr Luna Arjona ceased his official radiology work at Hospital Civil and devoted himself entirely to surgery.

During the 1940s, new hospitals appeared, such as the Sanatorio 18 de Julio (1943), the old Hotel Caleta Palace, an emblem of the city’s high society and tourism. The medical material was provided by large German companies which had collaborated effectively with the Franco regime. More than two and a half million pesetas were invested in this sanatorium which, thanks to its technical capabilities, was considered one of the best in Spain. The sanatorium’s director at that time was Dr José Lazárraga Abechuco.35 In 1945, the Sanatorio de Campanillas was opened in the district of the same name in Malaga, built by the Patronato Nacional Antituberculoso, the Spanish association for the fight against tuberculosis.35 For many years it was the main centre for the care of people with tuberculosis in Malaga and the surrounding province.

Also during the 1940s, doctors Francisco de Jorge Gallardo, Antonio Gómez de la Cruz Fernández, Antonio Padilla Villalobos, Narciso Barbero Tirado and Rodrigo Domínguez Estévez all started practising in Malaga as electroradiologists. Francisco de Jorge Gallardo (1912-1991) became a member of the college in Malaga in 1940. He specialised in paediatrics and electroradiology and worked for the Social Security as a radiologist at the Instituto Nacional de Previsión, the Spanish national insurance organisation, from June 1948. Antonio Padilla Villalobos (1918-1980) became a member of the college in Malaga in 1945. He opted first for general medicine and then decided to specialise in radiology. In 1946, he received the First Prize in the Gálvez Ginachero Awards for his work “Assessment of the different exploratory methods in the diagnosis of mitral valve lesions”, in which he demonstrated his extensive radiological knowledge of the thorax.38 Antonio Gómez de la Cruz Fernández (1921-?) became a member of the college in Malaga in 1944 and specialised in electroradiology and gastrointestinal surgery. He was a member of the Scientific Section of the Official College of Physicians of Malaga. In May 1948, he received the 1947 Gálvez Ginachero Award.42 Narciso Barbero Tirado (1888-?), military doctor, became a member of the college in Malaga in 1947 after practising for 34 years. He was head of Military Health and director of the Hospital Militar, where he was in charge of the X-ray Department until his retirement in 1950.

Rodrigo Domínguez Estévez (Fig. 9) was the only doctor who exclusively specialised in electroradiology at that time. He studied in Seville, graduating in 1941, and was a resident in electroradiology at the Faculty of Medicine of Madrid, where he specialised with Dr Carlos Gil y Gil. He became a member of the college in Malaga in 1943 and set up his private clinic next to Dr Gálvez Ginachero’s sanatorium,42 where it still is, run by his son, Dr Javier Domínguez Mayoral. He had a great capacity for work. When he arrived in Malaga, he obtained the position of head of the radiology department that Hospital Civil had just advertised, and years later, in 1956, he would obtain the position of head of the electroradiology department at Residencia Sanitaria Carlos Haya. In 1957, he was deputy secretary of SEREM on the new Board of Directors, chaired by Dr Francisco Arce Alonso.41

Historical references and epilogueThere are other published studies on the history of radiology in Spain that share some similarities with this study. The doctoral thesis of Dr José Enrique Millán Suárez, “History of radiology in Galicia”,43 also extends until 1940, when radiology was consolidated as an essential speciality in medical practice. The studies by Villanueva et al.44,45 and Sáez et al.46 describe the beginnings of radiology in the Spanish military sphere, and date the first hospital X-ray facility as being in the Murcia region in October 1903. In “Science and technology in Granada at the beginning of the century: the impact of the discovery of X-rays (1897–1907)”, Medina Domench et al.18 provide important historical information about that time. Both Felip Cid47 and Dr Portolés Brasó in her doctoral thesis7 document the history of radiology in Catalonia and Spain through Dr César Comas Llavería (1874–1956), a renowned radiologist both in Spain and abroad. It would be interesting to rescue from history the beginnings of radiology in other Spanish cities, especially the economically and socially important cities like Madrid, Seville, Valencia, Bilbao and Zaragoza.

In Malaga, the assimilation and evolution of the diagnostic and therapeutic use of radiology was slow and determined by the social, economic and cultural circumstances of the time. However, a number of outstanding, studious doctors with a will to overcome were able to raise medical practice to a level comparable to that of other provinces of similar characteristics. The weak economic growth in the 1950s and 60 s, along with acceptance of the concept of health as a right, led to the creation of Hospital Carlos Haya in Malaga, and that meant new specialists had to be taken on. New private clinics and hospital radiological departments were created and expanded. The new diagnostic techniques (ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, etc.), the increase in the volume and level of complication of the examinations, as well as its use becoming universal in clinical practice, led to a boom in diagnostic imaging in the 1970s and 80 s. This would yield results from a legal point of view in 1984, with the appearance of Radiodiagnostics in the catalogue of medical specialities.

In memoriamDoctor Gabriel Prados Carmona died on 20 April 2017. This article is part of his doctoral thesis entitled “Evolution and development of radiology in Malaga”, which he defended on 17 December 2015 at the University of Malaga. Publication of the article in Radiología is concluding a previously agreed project and, at the same time, is a posthumous tribute to its author.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for the integrity of the study: GPC and FSP.

- 2

Study conception: FSP.

- 3

Study design: GPC and FSP.

- 4

Data acquisition: GPC.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: GPC and FSP.

- 6

Statistical processing: NP.

- 7

Literature search: GPC and FSP.

- 8

Drafting of the article: GPC and FSP.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: FSP.

- 10

Approval of the final version: FSP.

There are no conflicts of interest.

To Manuel Molina Gálvez, librarian of the Cánovas del Castillo Library, who directed us to interesting sources of information at a crucial point in the research.