To analyse the clinical impact of routine acquisition of susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies of the brain.

Material and methodsThis prospective observational study included all patients undergoing brain MRI including SWI during a 6-month period. Patients were divided into two groups based on the clinical information provided: Group 1 comprised patients in whom SWI acquisition formed part of the brain MRI protocol, and Group comprised patients who underwent SWI without these sequences being included in the protocol. We recorded patients’ age, sex, and risk factors (hypertension, history of brain trauma or intracranial vascular malformations). We analysed the SWI findings, whether these findings were visible on the other sequences, and whether identifying these findings resulted in substantial changes to the radiological report.

ResultsThere were 62 patients in group 1 and 79 in group 2. The groups were similar in age and risk factors. SWI findings resulted in substantial changes to the radiological report in 34% of the patients in group 1 and in 14% of those in group 2; this difference was statistically significant.

ConclusionSWI can help radiologists detect findings not seen on conventional brain MRI that sometimes result in substantial changes to the radiological report.

Analizar el impacto clínico de adquirir la secuencia de susceptibilidad magnética (SWI) de forma rutinaria en los estudios de resonancia magnética (RM) cerebral.

Material y métodosSe lleva a cabo un estudio prospectivo observacional unicéntrico durante 6 meses a pacientes a los que se le realizó una RM cerebral. Los grupos de estudio se establecieron basándose en la información clínica remitida: el grupo 1 de estudio está formado por aquellos pacientes a los que el radiólogo protocolizó la adquisición de la secuencia SWI, y el grupo 2, por aquellos a los que se les realizó la secuencia SWI sin haber sido protocolizada. Se recogen la edad, sexo y factores de riesgo (hipertensión arterial, historia de traumatismo craneal o de malformaciones vasculares intracraneales). Se analizaron los hallazgos en la secuencia de SWI, si estos eran visibles en el resto de las secuencias y si su identificación suponía cambios sustanciales en el informe radiológico del paciente.

ResultadosEl grupo 1 estaba formado por 62 pacientes y el grupo 2, por 79. No hubo diferencias al comparar la edad y los factores de riesgo entre los dos grupos. En el grupo 1, los hallazgos de la SWI supusieron un cambio en el informe radiológico en el 34% de los pacientes, y en el grupo 2, en un 14%: las diferencias fueron estadísticamente significativas.

ConclusiónLa secuencia SWI puede ayudar al radiólogo a detectar hallazgos adicionales a las secuencias convencionales en la RM cerebral, que en algunos casos suponen un cambio en el informe radiológico.

Susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) is an MRI sequence that is especially sensitive to magnetic field inhomogeneities.

It was first used in the 1990s, when it was originally called “VEN BOLD” or high-resolution venography dependent on the level of oxygen in the blood, and was used as a way of visualising the veins, i.e. to perform a “venography”, but without administering contrast thanks to the paramagnetic effects of deoxyhaemoglobin that acts as intrinsic contrast. In 2004, it was renamed susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) because it was seen that it provides much more information beyond venography.1,2

It is based on a gradient T2*-3D echo sequence combined with a long TE that will enhance the effect of susceptibility and utilises the magnitude and filter of the phase information.

GRE sequences are sensitive to tissue susceptibility differences because they cannot refine out-of-phase spines due to magnetic field heterogeneities. Classic T2*GRE sequences have been traditionally used to detect iron, blood degradation products and calcifications. Modern SWI sequences incorporate several features and technical improvements that make them superior.3,4 They are usually 3D, so they can be acquired with a thinner cutting thickness and smaller voxel size. Flow compensation is used in the three directions of space to reduce artefacts, and is acquired in parallel to reduce acquisition time. Single or multiple echoes can be acquired at a certain repetition time (RT), but one of the keys to this sequence is that the phase and magnitude information is processed and displayed independently or in combination to help the diagnosis.5–7

The typical image parameters include an RT=25–50ms, an ET=20–40ms and an inclination angle=15°–20°. The magnitude and phase data are reconstructed separately.

The magnitude image is saved for diagnostic purposes, and is shown as a background tissue with a contrast similar to the spin density.

The phase data is post-processed so that they can be used clinically. The raw phase data show the heterogeneities of the magnetic field, as well as the distortions due to the interface between the air and the bone of the skull base. Subsequently, digital filtering is done to eliminate low-frequency fluctuations and a series of local phase correction algorithms to eliminate skull base artefacts. The result is the image of the filtered phase, which is the one that is finally shown for diagnostic purposes.6–8

In that image of the filtered phase, blood degradation products, i.e. paramagnetic substances, have a signal intensity opposite to diamagnetic substances.9,10 It is important to know how to interpret these images, since the different manufacturers of MRI devices show it differently: paramagnetic substances are white in Siemens® and Canon® and black in Philips® and GE®. The phase mask is created from the filtered phase to accentuate tissues with different susceptibilities. The magnitude image is digitally multiplied by the mask phase several times until a suitable mixture is obtained. The result is the SWI image, which simultaneously contains the magnitude and phase information, and is the one used for diagnostic purposes. In addition, minimum intensity projections (mIP), whose cutting thickness varies, can be shown to better identify hypointense lesions.

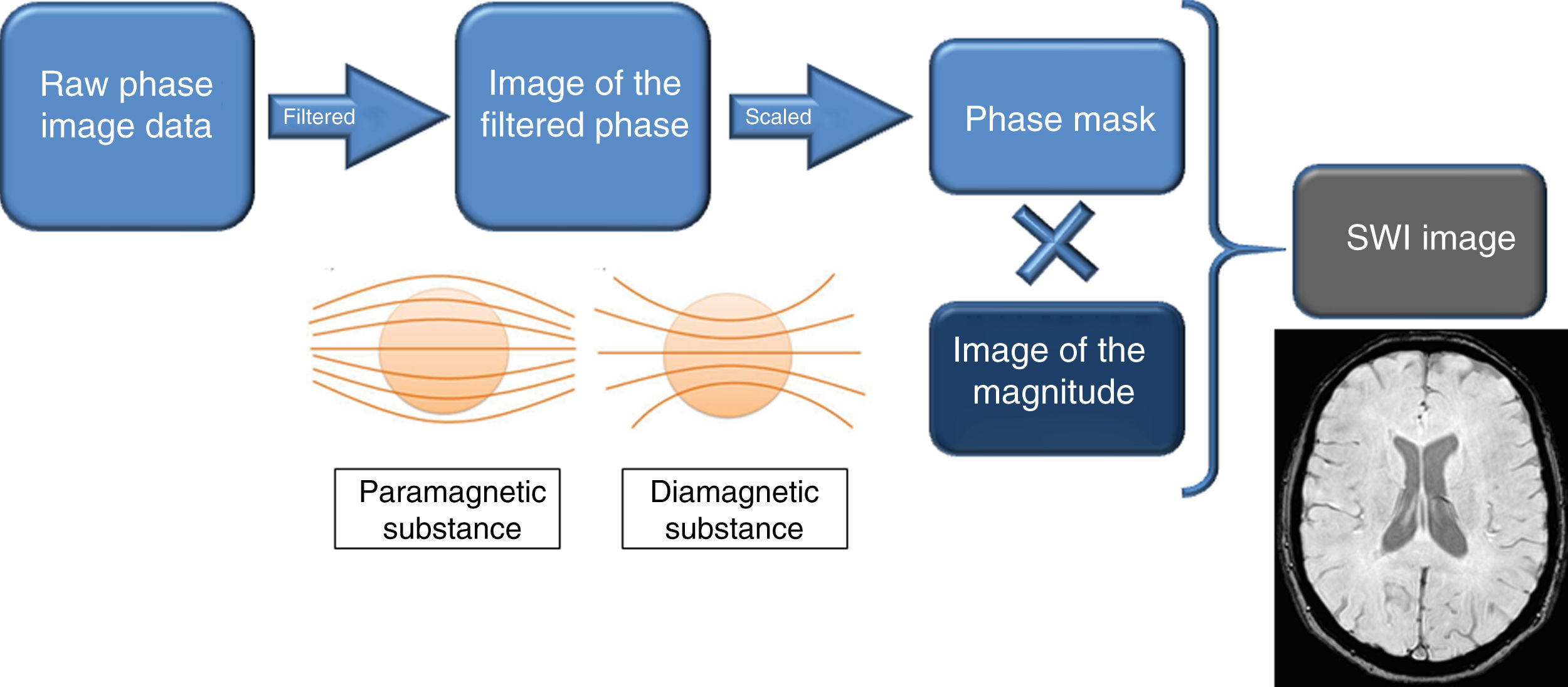

These physical basis are summarised by a diagram represented in Fig. 1.

Diagram of the physical basis of the magnetic susceptibility sequence. In the image of the filtered phase, the paramagnetic and diamagnetic substances have a different behaviour: the paramagnetic ones cause a divergence of the magnetic field lines and the diamagnetic ones, a convergence of these. This image of the filtered phase is shown differently on MRI equipment from different manufacturers, and it is important to know how to interpret it. From it, the phase mask is created, which, when digitally multiplied by the magnitude image, provides the SWI image. Therefore, SWI simultaneously contains information on the magnitude and the phase.

This way of acquiring it makes it so sensitive to the alterations of the magnetic field that it is used to explore the differences in magnetic susceptibility between tissues.

Therefore, this will allow differentiating between paramagnetic substances, such as haemosiderin and deoxyhaemoglobin (blood degradation products) and diamagnetic substances, such as calcifications and mineral deposits,9,10 which is a great advance for neuro-radiological images and is a very useful sequence for the diagnosis of multiple pathologies, not only vascular, but also neurodegenerative, demyelinating diseases, dementia, infections, trauma and tumours.1

In the specialised literature, there are multiple studies describing its qualities and demonstrating its advantages over other sequences for the diagnosis of the described pathologies, and its field of application is increasingly wide.1,6,7 Therefore, there comes a time when its acquisition is considered within the basic study protocol.

The objective of this study is to analyse the clinical impact that the acquisition of SWI would have on a routine basis or if, on the contrary, it should be linked to diagnostic suspicion.

Material and methodsPatientsFrom August 2016 to January 2017, a prospective study approved by the research ethics committee of Galicia (Xunta de Galicia [Regional Government of Galicia], Ministry of Health) was conducted, which included all patients who were asked to undergo a brain MRI performed in a 1.5T MRI scanner.

Two study groups were made based on the acquisition of the SWI sequence. Group 1 consisted of those patients to whom the neuroradiologists (with six and ten years of experience, respectively) protocolised the acquisition of the SWI sequence according to the clinical information of the application, the personal history and the cardiovascular risk factors. Senior radiodiagnostic technicians, who were unaware of the reason for this study, were asked to acquire the SWI sequence from patients who had no protocol for their acquisition, forming group 2 of the study (patients who would not have undergone this sequence if this study had not been done).

In all cases, data on the epidemiology of the patients were collected: gender, age, patient history and clinical information submitted by the clinician. Regarding the personal history of interest, risk factors were collected for the presence of blood remains: hypertension, history of traumatic brain injury and known history of intracranial vascular malformations, variables that were obtained by searching the patients’ medical records.

Subsequently, the findings of the SWI sequence were analysed and correlated with the risk factors of each subject and with the clinical information that was sent from each patient. Physiological calcifications that may appear in the central nervous system that lack pathological significance, such as calcifications of the pineal gland or choroid plexus, were not taken into account.

The images were studied independently by a neuroradiologist with ten years of experience and a third-year resident and it was also studied whether these findings could be identified in the rest of the acquired sequences. It was analysed whether these findings which were only visible in the SWI were reflected in the report, and if they changed the conclusion of the report in a relevant way.

MRI protocolAll studies are performed on a Philips® Ingenia resonance device (1.5T, Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands) using a 32-channel head antenna. The basic brain MRI protocol includes a 3D T1 sagittal sequence, 3D sagittal flair, axial T2 and axial diffusion.

The SWIp sequence was acquired with the following technical parameters: FOV 230×186; matrix size, 272×220; mean voxel size, 0.85mm×0.85mm×2mm; ET 12ms; shortest RT and inclination angle of 20° with SENSE, and 130 cuts with a thickness of 2mm. The total acquisition time of this sequence was 5:08min.

In all cases, the following were stored in the PACS (picture archiving and communication system) the combined maps of post-processing the magnitude and phase (SWIp) and the maps of the filtered phase where, in the equipment used, paramagnetic substances (venous blood) are hypointense while diamagnetic substances (calcifications) are hyperintense.

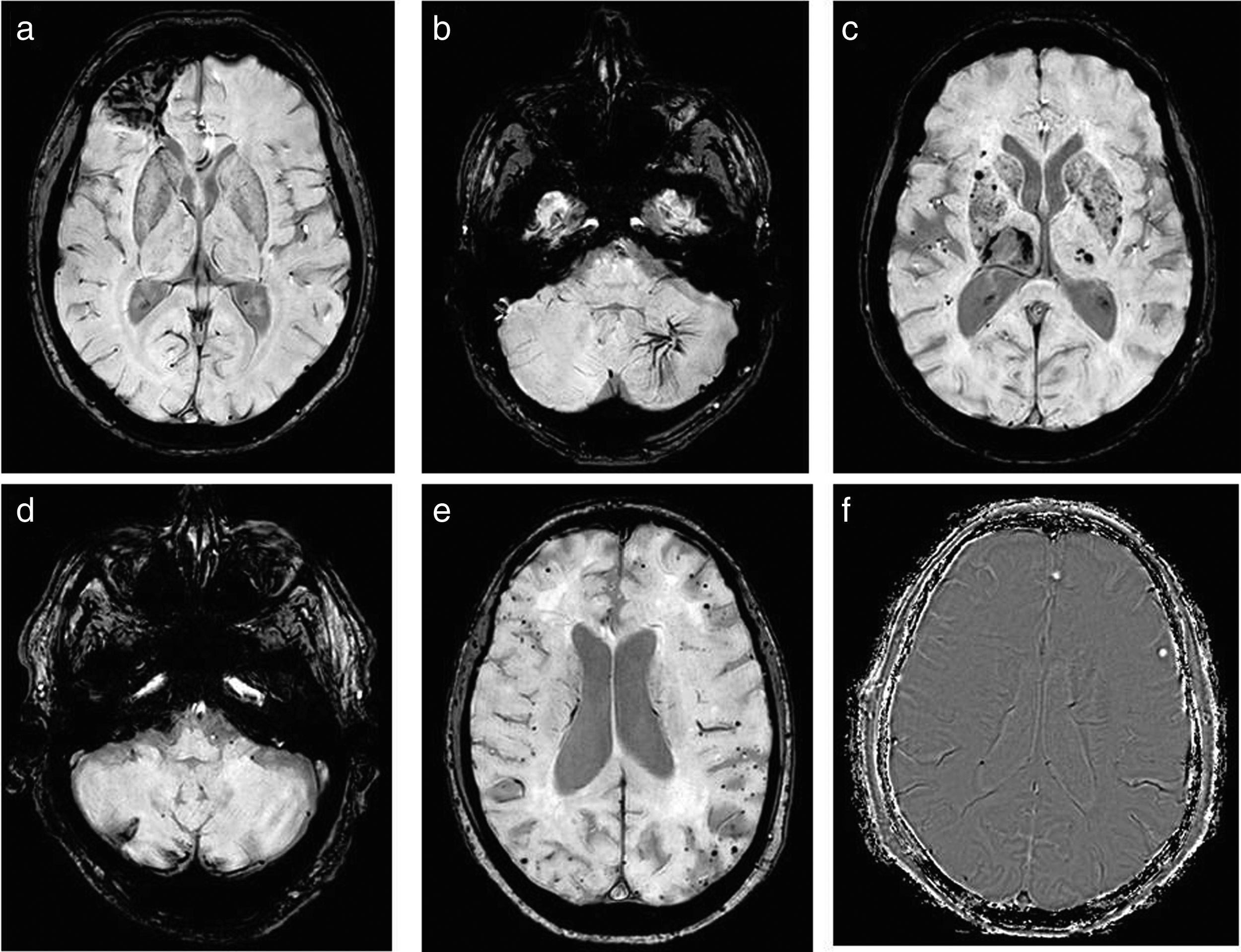

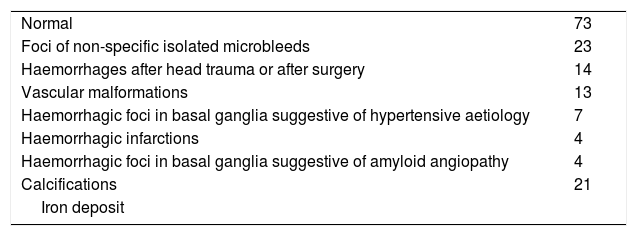

Analysis of the imagesAll the images of the SWI sequence were thoroughly analysed by two radiologists (a neuroradiologist with ten years’ experience and a 3rd year resident), and all the findings were recorded, grouped in the following diagnoses: non-specific isolated microhaemorrhage foci, haemorrhages after cranial trauma or after surgery, vascular malformations, haemorrhagic foci in basal ganglia suggestive of hypertensive aetiology, haemorrhagic infarctions, haemorrhagic foci in basal ganglia suggestive of amyloid angiopathy, calcifications and iron deposits, all summarised in Table 1. Several examples are shown in Fig. 2.

Radiological findings found in the SWI sequence.

| Normal | 73 |

| Foci of non-specific isolated microbleeds | 23 |

| Haemorrhages after head trauma or after surgery | 14 |

| Vascular malformations | 13 |

| Haemorrhagic foci in basal ganglia suggestive of hypertensive aetiology | 7 |

| Haemorrhagic infarctions | 4 |

| Haemorrhagic foci in basal ganglia suggestive of amyloid angiopathy | 4 |

| Calcifications | 21 |

| Iron deposit |

Examples of findings visualised in SWI: (a) bleeding after TBI. (b) Vascular malformations; in this case, an anomaly of the venous development of the left cerebellar hemisphere. (c) Microbleeds in basal ganglia of hypertensive aetiology. (d) Haemorrhagic infarctions; in this example, in the right cerebellar hemisphere with superficial haemosiderosis. (e) Amyloid angiopathy, which is identified as peripheral punctate haemorrhages. (f) Calcifications, typified using the mask where hyperintense are visualised.

Subsequently, the rest of the acquired pulse sequences were analysed to see if these findings were identifiable.

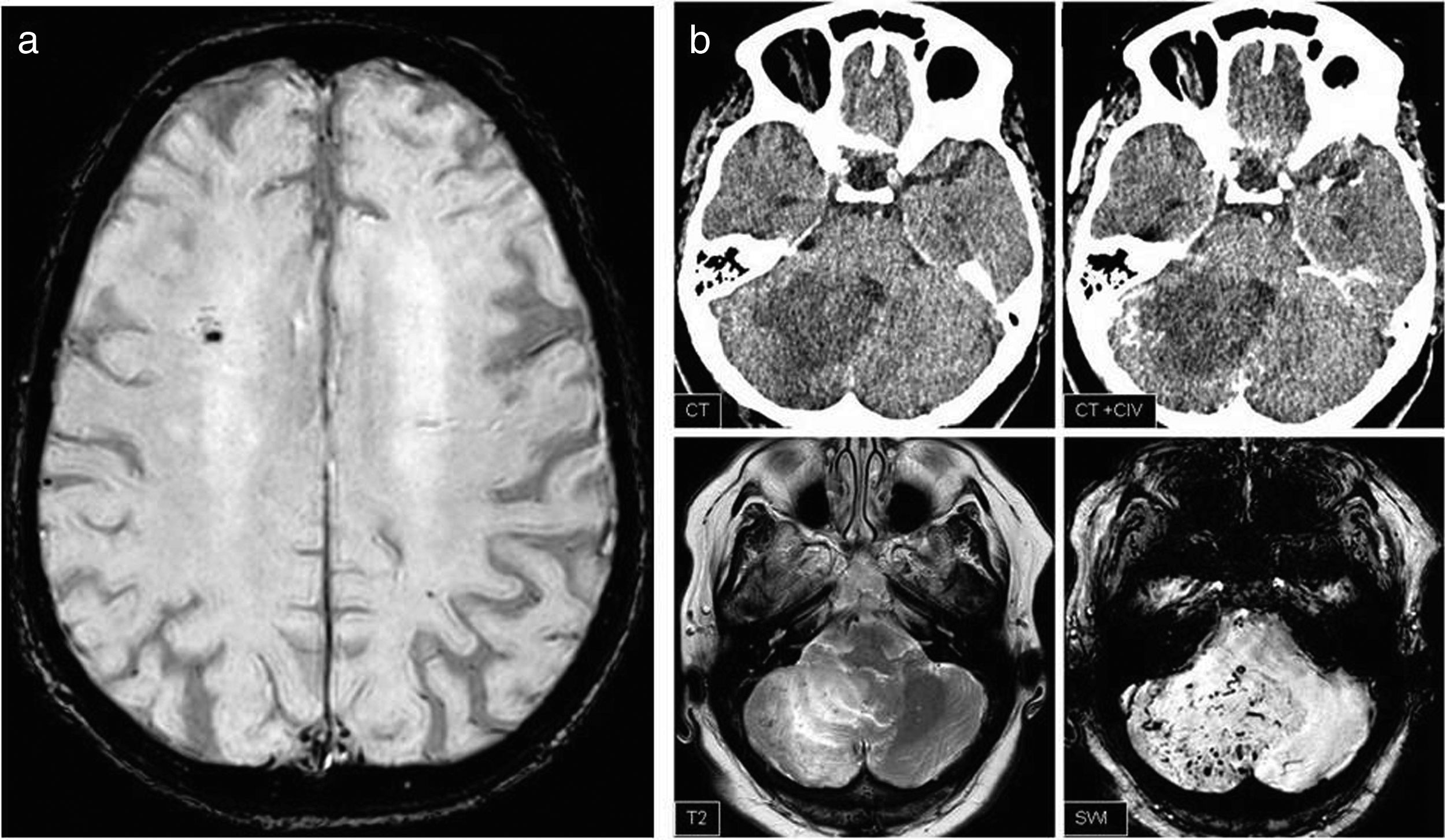

Finally, the SWI findings were classified as: (a) alterations identified in the SWI sequence that have no clinical relevance (such as demonstrating blood remains in a surgical bed) or that are identified in the rest of the sequences and that therefore their visualisation in SWI does not imply a change in the radiological report and (b) SWI findings that have pathological value, that are not identified in other sequences or, in the event that they are visualised, would not be conclusive, that they will lead to a change in the report (Fig. 3).

(a) General finding: isolated microbleed, which does not change the report or patient management. (b) Relevant finding: hypodense lesion in cerebellar hemisphere difficult to interpret in computed tomography despite intravenous contrast (IVC), which on MRI shows vessels swollen in SWIp and corresponds to an arteriovenous malformation.

The SPSS® (Chicago, Illinois) statistical programme, version 15, was used, employing parametric tests. The results of the demographic data are shown as mean±standard deviation. To compare both groups a Student's t-test was performed for independent samples, considering the differences to be statistically significant when p<0.05.

ResultsA total 141 patients – 74 men and 67 women – were recruited, with a mean age of 59.5 years. Group 1 had 62 patients and group 2 had 79 patients.

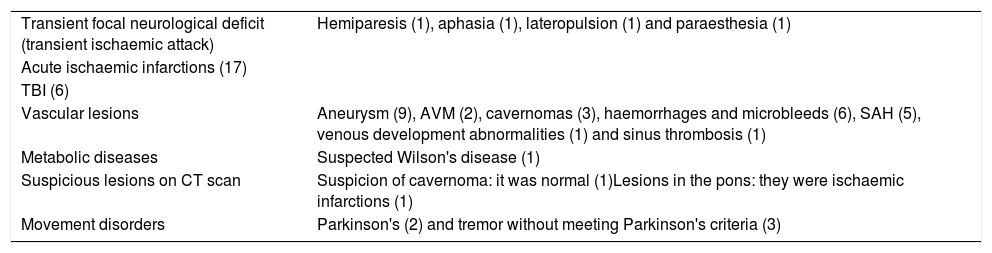

Approximately 47 different types of clinical information were documented, many of them grouped by common characteristics. Table 2 shows the clinical information that was considered for the programming of the SWI.

Clinical information considered indicative of programming SWI.

| Transient focal neurological deficit (transient ischaemic attack) | Hemiparesis (1), aphasia (1), lateropulsion (1) and paraesthesia (1) |

| Acute ischaemic infarctions (17) | |

| TBI (6) | |

| Vascular lesions | Aneurysm (9), AVM (2), cavernomas (3), haemorrhages and microbleeds (6), SAH (5), venous development abnormalities (1) and sinus thrombosis (1) |

| Metabolic diseases | Suspected Wilson's disease (1) |

| Suspicious lesions on CT scan | Suspicion of cavernoma: it was normal (1)Lesions in the pons: they were ischaemic infarctions (1) |

| Movement disorders | Parkinson's (2) and tremor without meeting Parkinson's criteria (3) |

SAH: subarachnoid haemorrhage; AVM: arteriovenous malformation.

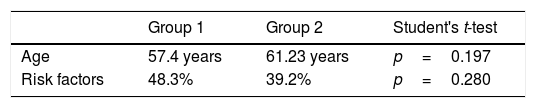

No statistically significant differences were found when comparing age and risk factors between the two groups (Table 3).

The SWI sequence was completely normal in 73 and showed no signal alteration: 28 (45%) in group 1 and 46 (58%) in group 2.

Those who presented findings in SWI (2) were diamagnetic substances: in one patient it was parenchymal calcifications (corroborated in a previous CT scan), sequelae of remote tuberculosis, and another in the brain sickle, which corresponded to an ossification of it. The rest were paramagnetic or ferromagnetic substances: one of them had iron deposits in the basal ganglia and the rest were blood degradation products.

Isolated hypointense point foci were identified in 23 SWI, 10 of which belonged to group 1 and 13 were part of group 2.

Haemorrhages associated with head injuries or surgery were identified in 14 patients and in 13 patients with vascular malformations, all of them from group 1. Table 1 summarises the SWI findings of all the patients included in the study.

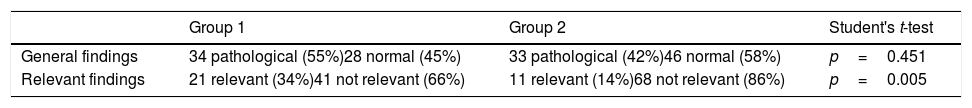

When comparing the SWI findings between the two groups, there were significant differences between them (Table 4):

- •

In group 1, in 34 patients (55%) there were findings in the SWI and in 21 patients (34%) the report was changed based on these findings: five cases by supra and infratentorial haemorrhagic foci predominantly in base ganglia that were compatible with chronic hypertensive encephalopathy, in five patients vascular alterations were identified (two corresponded to arteriovenous malformations, two to venous development abnormalities and in one case dilated drainage veins were identified, secondary to transverse sinus thrombosis), four cases of amyloid angiopathy (one of them also showed superficial siderosis), three patients with multiple cavernomatosis and, finally, three cases with intraparenchymatous haematomas (one case corresponded to a patient with a recent aneurysm clipping).

- •

In group 2, the SWI presented findings in 33 patients (42%); of these, only in 11 cases out of 79 (14%), these findings led to a change in the radiological report, which were as follows: in three patients an amyloid angiopathy was suggested (two had peripherally distributed microbleeds and one superficial siderosis), three presented anomalies of venous development, in three cases blood remains were revealed in infarctions not detected in the rest of the sequences, and, finally, in two cases chronic hypertensive encephalopathy was suggested due to microbleeds in the grey nuclei of the base.

Relationship between general and relevant findings between the two study groups.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Student's t-test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General findings | 34 pathological (55%)28 normal (45%) | 33 pathological (42%)46 normal (58%) | p=0.451 |

| Relevant findings | 21 relevant (34%)41 not relevant (66%) | 11 relevant (14%)68 not relevant (86%) | p=0.005 |

With this work, it has been studied if the fact of including SWI as a routine sequence in the basic protocol of brain MRI provides relevant data that lead to an important change in the diagnosis and, therefore, in the management of the patient. For this, an observational study has been carried out: the SWI findings have been compared in patients in whom, according to the clinical information provided by the requesting physician, the personal history and risk factors of each patient, the radiologist considers it necessary that it be acquired, and so it is protocolised, and has been compared with the SWI findings in a control group in which a priori it was not considered necessary to acquire it.

The physical basis of the SWI sequence allow for the detection of all those heterogeneities in the magnetic field.1–6

In the scientific literature, there are multiple studies that document its usefulness for the diagnosis of certain pathologies, mainly venous abnormalities, haemorrhages or even the detection of lesions with calcium or iron deposits, thanks to their property of being sensitive to substances that distort the magnetic field, but taking a step more than the classic T2* sequences, since when acquiring the phase it makes it possible to differentiate the paramagnetic substances from the diamagnetic ones.7–9

These characteristics have demonstrated the effectiveness of the SWI sequence compared to T2*3 and its cost-effectiveness when diagnosing microbleeds4,11; for example, in cases of high blood pressure, chronic traumatic brain injury (TBI)12 or to demonstrate blood remains in diffuse axonal injury.13 It has also proven its usefulness in cases of amyloid angiopathy,14 and, more recently, it is being used in studies of tumours and multiple sclerosis.15–17 So many benefits have been described that there are even authors who have recommended their acquisition in the routine protocol in the described pathologies.1

Since more and more applications of this sequence are being demonstrated, it can be considered to do it routinely to all patients, which would mean increasing the ET. However, given the significant demand for imaging tests in radiodiagnostic services, it is essential to optimise the protocols and machine times, doing studies aimed at responding to the clinical reason that motivated the request for the test.

The results of the work show that in the group in which its acquisition was protocolised, SWI did show relevant findings. On the other hand, when it was acquired routinely without previously selecting the patients, which is what happened in group 2, there were significant findings in SWI in 11 patients (14%): in three patients, an amyloid angiopathy due to subcortical microbleeds was suggested, none of which presented cognitive impairment and the clinical attitude was not changed; the three anomalies of venous development had no associated vascular malformations, so it can be considered practically a finding without relevance; in the three cases in which blood remains were demonstrated in chronic infarctions, the clinical management did not vary, and, finally, in two cases it was suggested to rule out a chronic hypertensive encephalopathy due to microbleeds in the grey nuclei of the base and the management was not changed either. Therefore, taking into account that adding this sequence routinely involves machine time, each centre or each work team should consider whether its introduction is convenient, because there are relevant findings that change the radiological report, although in this study they did not result in a change in the management of these patients.

This study has several limitations: the main one is the study design itself, since group 1 was formed based on the information submitted and the risk factors. In many cases, the information provided about the patient is scarce or incomplete, and also, sometimes, the risk factors are not properly collected. In addition, group 2, in which it was not protocolised, but it was the technician who, depending on the available machine time, acquired it or not, was not randomised, but, as mentioned, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups. Another limitation is the fact that it is considered pathological, since, for example, the identification of some isolated hypointense punctate image in SWI was considered non-specific, not giving clinical relevance in either of the two groups.

In conclusion, SWI is a sequence that provides very relevant information with multiple clinical applications. Including it in the basic protocol of routine study can provide data that change the radiological report, but since it entails an increase in the examination time, each centre or each work team must assess its routine acquisition.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for the integrity of the study: EUP, ESA, NSP, AVC and CJB.

- 2.

Study conception: EUP, ESA and NSP.

- 3.

Study design: EUP and ESA.

- 4.

Data collection: EUP, ESA, NSP, AVC and CJB.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: EUA and ESA.

- 6.

Statistical processing: EUP and ESA.

- 7.

Bibliographic search: EUP, ESA, NSP, AVC and CJB.

- 8.

Drafting of the article: EUP and ESA.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: EUP, ESA, NSP, AVC and CJB.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: EUP, ESA, NSP, AVC and CJB.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Utrera Pérez E, Santos Armentia E, Silva Priegue N, Villanueva Campos A, Jurado Basildo C. ¿Se debe incluir la secuencia de susceptibilidad magnética en el protocolo de resonancia magnética cerebral básico? Radiología. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rx.2019.12.006