Follow-up of patients with gliomas remains a challenge in the field of the neuro-oncology. The RANO group published its first follow-up criteria for high-grade gliomas in 2010, originally focused on clinical trials, but can served as a guide in the clinical practice. Subsequently, variations were published, including follow-up criteria for low-grade tumours, immunotherapy, and modifications to the original criteria.

In 2023, they published a more comprehensive guide, RANO 2.0, which included all glioma types and different treatments. For the first time, they considered the latest WHO classification and objective data in addition to expert opinion. RANO 2.0 establishes which type of MRI should be used for the baseline MRI, describes the different responses of contrast-enhanced and non-contrast-enhanced tumour components, and determines in what circumstances a confirmatory MRI is required.

In light of these changes, it is worth reviewing these new criteria to enable a better understanding of the revisions and their applicability in routine radiological practice.

El seguimiento de los pacientes con gliomas sigue siendo un reto en el campo de la neuro-oncología. El grupo Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology Working Group (RANO) publicó sus primeros criterios de seguimiento para gliomas de alto grado en 2010, originalmente centrados en ensayos clínicos, pero que pueden servir de guía en la práctica clínica. Posteriormente, se publicaron variaciones incluyendo criterios de seguimiento para tumores de bajo grado, inmunoterapia y modificaciones de los criterios originales.

En 2023, se publicaron los RANO-2.0 en un intento de ser una guía más global, incluyendo todos los tipos de gliomas y los diferentes tratamientos. Por primera vez, utilizan datos objetivos además de la opinión de expertos y contemplan la última clasificación de la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). Los RANO-2.0 determinan la resonancia magnética (RM) óptima para RM basal, la respuesta de los componentes tumorales captantes y no captantes, y la necesidad de RM confirmatoria.

Ante este cambio, es oportuno revisar estos nuevos criterios, permitiendo una mejor comprensión de las modificaciones y su aplicabilidad a la práctica radiológica rutinaria.

In Spain, the incidence of central nervous system (CNS) tumours is around 10.2 cases per 100,000 population per year,1 with gliomas accounting for 14.2% of CNS tumours overall. The majority (50.1%) of malignant CNS tumours are glioblastomas (GB) and around 30% are represented by the other types of glial lesions.2 The standard treatment for more than two decades proposed by Stupp (STUPP),3 consisting of surgery followed by radiotherapy/chemotherapy (maximum safe resection possible followed by radiotherapy [RT] and temozolomide in concomitant and adjuvant treatment), has improved survival, but mortality rates remain high. Five-year survival after diagnosis is only 35.7%,2 despite the testing of new systemic therapies such as antiangiogenic drugs,4 immunotherapy,5 oncolytic viruses,6 therapies targeting gliomas with a mutation in the gene for the enzyme isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)7 and local treatments with electromagnetic fields (TTFields).8

Radiology plays a key role in the clinical management of patients with these tumours, both in diagnosis, treatment planning and post-treatment follow-up. However, radiological follow-up is complex and poses a challenge in radiology.9 Gliomas are difficult to measure because of their irregularity, infiltrative appearance with imprecise borders and heterogeneity. There are several components to the heterogeneity, such as contrast-enhancing and non-contrast-enhancing regions, haemorrhagic areas, calcifications, necrotic or cystic areas and vasogenic oedema.10,11 Treatments then induce changes in the blood-brain barrier and cause inflammation and gliosis, which can result in new regions of contrast enhancement or signal alteration in T2-weighted and FLAIR resonance sequences (T2/FLAIR), making it difficult to differentiate between treatment-related changes and underlying residual tumour.12,13

Treatment response criteria, which include radiological assessment,14,15 play an essential role in the evaluation of these patients, making it more reliable and reproducible, and providing a common language that facilitates the transmission of radiological information between the different specialists.16 These criteria are used in clinical trials and efforts have been made to use them as a guide to tumour response in clinical practice.17 However, they cannot be fully extrapolated, as they were designed to assess the efficacy of treatments with the fewest biases, which may not always be aligned with the best management decision for the individual patient.

Since the publication of the first Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO)Working Group criteria,18 successive updates have been made in an attempt to improve the limitations of the previous criteria.19–21 The new RANO criteria (RANO-2.0) were recently published.14 The aim is that these should be more comprehensive guidelines, including all types of gliomas and the different treatments. For the first time, they are based on data analysis, not just expert opinion,22 and they also take into account the changes in tumour classification proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2021.23

We have reviewed here the changes over time in the radiological response criteria in gliomas, and the new RANO-2.0 criteria, and discuss their applicability in routine radiology practice.

Changes over time in the radiological criteria for tumour responsePre-RANO eraThe first criteria were proposed by Levin et al., in the late 1970s, based on qualitative radiological evaluation, neurological assessment and considering the use of corticosteroids.24 In 1990, Macdonald et al. published criteria that marked the transition from subjective interpretation to objective, radiologically based criteria.25 These criteria advocated the two-dimensional (m2D) measurement of contrast-enhancing (CE) tumours previously recommended by the WHO criteria,26 and standardised the definition of radiological response, establishing four categories adopting oncology terminology: complete response (CR); partial response (PR); disease progression (DP); and stable disease (SD). Although with limitations, these criteria were used for over 20 years and are the fundamental framework for response assessment and radiological interpretation.18

Later, the 2000s saw publication of the tumour response criteria in solid tumours (RECIST),27 the subsequent update of which is known as RECIST 1.1.28 Although these guidelines cannot always be applied in gliomas, they provided the concepts and measurement limits of measurable lesions (ML) and target lesions (TL), and specified the non-measurement of the tumour cystic component.

In 2005, publication of the results of STUPP therapy demonstrated improvement in median survival from 12.1 to 14.6 months.3 Along with this improvement in prognosis, it was reported that, after RT, a third of patients on this treatment regimen showed an increase in the size of the contrast-enhanced region in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the irradiated area, followed by a subsequent improvement or stabilisation.29,30 This was called pseudoprogression (PsP), a phenomenon more common in those with methylation in the enzyme O6 methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT)31 and more prevalent in the first three months after RT.32 Similarly, at the end of the 2000s, linked to the beginning of the use of antiangiogenic drugs for recurrent gliomas,33,34 bevacizumab in particular,35 the concept of pseudoresponse (PsR) emerged. This phenomenon corresponds to a rapid decrease in contrast enhancement caused by the effect of these drugs on the blood-brain barrier rather than a true tumour response,32 with an associated increase in the size of non-contrast-enhancing (nCE) tumour in T2/FLAIR in up to 40% of cases.36

The description of both phenomena postdated the classification by Macdonald et al. and so generated new difficulties in the assessment of tumour response, requiring the development of new criteria.

RANO eraThe multidisciplinary and international RANO group published its first criteria in 201018 and, subsequently, successive updates19–21 (Table 1), providing guidelines to address the new challenges in the follow-up of patients with gliomas. These criteria are based on the Macdonald criteria and incorporate concepts from the RECIST, WHO and even Levin criteria.

Comparison of different RANO tumour response criteria.

| Criteria | RANO-2010 | iRANO | mRANO | RANO 2.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contrast-enhancing tumour | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Non-contrast-enhancing tumour | Yes (subjective) | No | No | Yes (objective) |

| Measurement | 2D | 2D | 2D = 3D | 2D > 3D |

| Number of target lesions | Up to 5 | Up to 5 | Up to 5 | Up to 3a or 4b |

| Baseline MRI | Postoperative | Postoperative | Post-radiotherapyc | Post-radiotherapyc |

| Confirmatory MRI | Optional | <6 months | Always | <3 monthsd |

iRANO: RANO criteria for immunotherapy; mRANO: modified RANO criteria; RANO: Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology Working Group; RANO-2010: initial RANO criteria; RANO 2.0: new RANO criteria; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

2D: two-dimensional measurement, 3D: volumetric measurement.

They highlight the deficiencies of the Macdonald criteria,18 being more specific and reproducible, recognising that contrast enhancement is not specific to tumour tissue and accepting the existence of nCE tumour.30,32,37

These criteria:

- -

Maintain the m2D, incorporating the concept of ML and the possibility of up to five TL in the evaluation of CE tumours, and describe how to measure cystic or pericavitary lesions.

- -

They establish the need for a baseline MRI (bMRI), using the postoperative MRI (post-op MRI) for this purpose, which should be performed within the first 24−72 h (preferably 24−48 h). Post-op MRI is also useful for assessing possible areas of ischaemia in the surgical bed which might be detected in subsequent follow-ups. Beyond 72 h, it should not be performed due to the risk of reactive or inflammatory enhancement which may overlap with residual CE tumour.37

- -

Introduce the concept of PsP, as it cannot be differentiated from real growth in CE tumours, even with the use of advanced MRI sequences.9 In fact, they can eventually be differentiated, as PsP improves over time.30,31 It is therefore established that, in the first three months after RT, DP can only be definitively diagnosed if the enhancement is outside the irradiation field or if there is pathology confirmation, although even the histological criterion has its limitations.18

- -

Incorporate the subjective assessment of nCE tumours, helping to address the phenomenon of PsR. They clarify that these changes should not be the result of comorbid events (for example, effects of RT, demyelination, ischaemic injury, infection, seizures, postoperative changes or other treatment effects).

- -

As tumour responses must be maintained over time, and time course is important in identifying PsP and PsR phenomena, they include the possibility of performing a confirmatory MRI (conMRI) at least four weeks later.

The RANO group also recognised the need for an assessment for low-grade gliomas (RANO-LGG), publishing specific criteria in 2011.19 These include the measurement of nCE tumours in T2/FLAIR and the possibility of a minor response (MR) is included, as the responses are usually relatively modest.

iRANO criteriaThe introduction of immunotherapy in the treatment of gliomas created the need in 2015 to establish specific criteria (iRANO).20 These treatments produce later responses, and due to their mechanism of action, they can cause increases in oedema and contrast enhancement.5,38 The criteria maintain the use of post-op MRI as bMRI and propose that if DP is suspected on MRI within the first six months after starting immunotherapy, but the patient is clinically stable, treatment should be continued with close monitoring and a conMRI performed within a maximum of three months. If the new MRI shows DP, the onset of DP will be considered as the date of the MRI when it was initially suspected.

Modified RANO criteriaThese modified criteria (mRANO) were published in 201721 after years using the original criteria, after doubts were raised about the benefit of the subjective assessment of nCE tumours36 or the m2D.39 The development of immunotherapy and the emergence of new treatments such as oncolytic viruses, which have been shown to induce a temporary worsening of contrast enhancement,5,6,40 also posed new difficulties.

The modified criteria state that the bMRI should be the post-radiotherapy (post-RT) MRI, they exclude the assessment of nCE tumours and determine that performing the conMRI is mandatory. For the first time, the possibility of volumetric measurement (m3D) is included, with a conversion table from m2D to m3D. A key difference from previous criteria is that a new ML does not directly imply DP, but must be added to the overall CE tumour burden to determine tumour response.

The mRANO also propose the standardisation of the MRI protocol through the international Brain Tumor Imaging Protocol (BTIP),41 necessary for clinical trials, but also adaptable to clinical practice (Table 2).

Brain MRI protocol for follow-up of gliomas (1.5 T or 3 T scanners).

| Sequence | Plane | Slice thickness | FOV | Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 3Da,b | Sagittal | 1 | 250 | 256 × 256 |

| FLAIRa,b | Axial | 3 | 240 | 304 × 200 |

| FLAIR | Coronal | 3 | 240 | 304 × 204 |

| DIFFUSIONa | Axial | 3 | 240 | 192 × 192 |

| SWI 3D | Axial | 2.3 | 240 | 256 × 168 |

| IV contrast (pre-bolusc) | ||||

| T2a | Axial | 3 | 240 | 384 × 302 |

| IV Contrast | ||||

| DSC PERFUSION (50 measurements) | Axial | 3 | 240 | 110 × 83 |

| T1 3Da,b | Sagittal | 1 | 250 | 256 × 256 |

| T1 2D | Axial | 3 | 240 | 320 × 198 |

DSC: dynamic magnetic susceptibility perfusion; FOV: field of view; IV: intravenous; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; SWI: susceptibility-weighted imaging.

Not necessary when using low Flip-Angles (30−35°) with repetition time (TR) 1000–1550 and echo time (TE) 25–35 (3 T) or 40–50 (1.5 T).57 The sequences marked in blue are additional sequences proposed as a routine protocol for follow-up care. In 3 T scanners, FLAIR-2D can be replaced by FLAIR-3D.

All these criteria have coexisted in recent years and are used in various clinical trials and, to a greater or lesser extent, in clinical practice.

Limitations of previous radiological criteria and response of the RANO groupDespite updates to the RANO criteria and their adaptation to new therapies for the treatment of gliomas, some limitations remain:

- -

They are based on a consensus of expert recommendations, but do not include clinical validation data to support decisions during follow-up.

- -

There are doubts about which of the different RANO criteria is best for assessing treatment response. For example, it is not clear whether post-RT MRI is better than post-op MRI as bMRI, whether nCE tumour assessment should be included or not,40 or whether m3D is superior to m2D.39,42 Additionally, the emergence of new treatments raises the question of whether, as with iRANO, each should have their own specific criteria.

- -

The introduction of IDH molecular status in the new WHO classification of diffuse gliomas in adults,23 also presents new challenges. IDH-mutated (IDHm) gliomas and some GB, such as the molecular GB (radiological pattern is low-grade but have mutations that meet the criteria for GB and behave as aggressively as classic GB), may not be contrast-enhancing or they may produce poorly defined faint enhancement.43,44 It can be difficult to decide which criteria to use in these cases and there is clearly a need to reassess non-enhancing tumours.

- -

Difficulties in identifying PsP and PsR persist, despite attempts by the RANO criteria to address this deficit by using conMRI to validate the response in cases of uncertainty. Although advanced MRI imaging techniques (perfusion, diffusion, spectroscopy or amide proton transfer [APT] weighted sequences) have shown potential utility in these situations,45 they have not been considered in the BTIP.

Attempting to address these limitations, Youssef et al. published a study comparing the RANO-2010, mRANO and iRANO criteria in 526 patients with newly diagnosed GB and 580 with recurrent GB.46 They found a good interobserver correlation for each criterion. However, in terms of progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), they found that RANO-2010 and mRANO have a similar correlation, while iRANO does not provide a significant benefit. They also concluded that post-RT MRI is better than bMRI and that conMRI is only useful within the first 12 weeks after RT. Moreover, they found that assessment of nCE tumours in GB does not improve the correlation with PFS and OS, even in the case of treatment with bevacizumab.

Although this study only evaluated patients with GB, the authors suggest that nCE tumour assessment could be useful in the absence of CE tumour in IDHm, but indicate that further studies are needed.

New RANO-2.0 criteriaThe new RANO-2.0 criteria were published following the evaluation by Youssef et al. of the previous criteria46 and taking into account the new WHO tumour classification.23 These new criteria are summarised below (Table 3), with highlighting of some of the more important points (Table 4).

Summary of tumour responses considered in RANO 2.0.

| Response criteria | Glioblastomas | IDH-mutant gliomas and other gliomas | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete response (must meet all criteria) | A. Measurable disease | Disappeared | Disappeared |

| B. Non-measurable disease | Disappeared | Disappeared | |

| C. New lesions | No | No | |

| D. Persistence over time | ≥4 weeks | ≥4 weeks | |

| E. Comparison MRI | Baseline MRI | Baseline MRI | |

| Partial response (must meet all criteria) | A. Measurable disease | ||

| 1. Target lesions | Reduction 2D: ≥50%, 3D: ≥65% | ||

| a. Contrast-enhancing tumour | Reduction | Reduction | |

| b. Non-contrast-enhancing tumour | Not applicable | Reduction | |

| 2. Non-target lesions | |||

| a. Contrast-enhancing tumour | Stable or reduction | Stable or reduction | |

| b. Non-contrast-enhancing tumour | Not applicable | Stable or reduction | |

| B. Non-measurable disease | |||

| a. Contrast-enhancing tumour | Stable or reduction | Stable or reduction | |

| b. Non-contrast-enhancing tumour | Not applicable | Stable or reduction | |

| C. New lesions | No | No | |

| D. Persistence over time | ≥4 weeks | ≥4 weeks | |

| E. Comparison MRI | Baseline MRI | Baseline MRI | |

| Minor response (must meet all criteria) | A. Measurable disease | Only applies to non- CE tumour Reduction 2D: 25%−50%, 3D: 40%−65% | |

| 1. Target lesions | |||

| a. Contrast-enhancing tumour | Stable | ||

| b. Non-contrast-enhancing tumour | Reduction | ||

| 2. Non-target lesions | |||

| a. Contrast-enhancing tumour | Stable | ||

| b. Non-contrast-enhancing tumour | Stable or reduction | ||

| B. Non-measurable disease | Not applicable | ||

| a. Contrast-enhancing tumour | Stable | ||

| b. Non-contrast-enhancing tumour | Stable or reduction | ||

| C. New lesions | No | ||

| D. Persistence over time | ≥4 weeks | ||

| E. Comparison MRI | Baseline MRI | ||

| Stable disease (must meet all criteria) | A. Measurable disease | ||

| 1. Target lesions | Not CR, PR, MR or DP | ||

| a. Contrast-enhancing tumour | Stable | Stable | |

| b. Non-contrast-enhancing tumour | Not applicable | Stable | |

| 2. Non-target lesions | |||

| a. Contrast-enhancing tumour | Stable or reduction | Stable or reduction | |

| b. Non-contrast-enhancing tumour | Not applicable | Stable or reduction | |

| B. Non-measurable disease | |||

| a. Contrast-enhancing tumour | Stable or reduction | Stable or reduction | |

| b. Non-contrast-enhancing tumour | Not applicable | Stable or reduction | |

| C. New lesions | No | No | |

| D. Persistence over time | ≥4 weeks | ≥4 weeks | |

| E. Comparison MRI | Baseline MRI | Baseline MRI | |

| Disease progression (must meet at least one of the criteria) | A. Measurable disease | ||

| 1. Target lesions | Increase 2D: ≥25%, 3D: ≥40%. Sustained in 2 consecutive MRI > 4 weeks | ||

| a. Contrast-enhancing tumour | Increase | Increase | |

| Confirmatory MRI | |||

| <12 weeks post-RT | Yes | Yes | |

| >12 weeks post-RT | Not necessary | Optional | |

| b. Non-contrast-enhancing tumour | Not applicable | Increase | |

| 2. Non-target lesions | |||

| a. Contrast-enhancing tumour | Increase | Increase | |

| b. Non-contrast-enhancing tumour | Not applicable | Increase | |

| B. Non-measurable disease | Increase in size, reaching at least 10 × 10 × 10 mm (2D or 3D) | ||

| a. Contrast-enhancing tumour | Yes | Yes | |

| b. Non-contrast-enhancing tumour | Not applicable | Yes | |

| C. New measurable lesions | Yes | Yes | |

| D. Leptomeningeal disease | Yes | Yes | |

| E. Persistence over time | ≥4 weeks | ≥4 weeks | |

| F. Comparison MRI | MRI with best response | MRI with best response | |

CE: contrast-enhancing; CR: complete response; DP: disease progression; IDH: isocitrate dehydrogenase gene; MR: minor response; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PR: partial response; RANO: Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology Working Group; RT: radiotherapy.

Key points in the assessment of tumour response using the RANO 2.0 criteria.

| The RANO2.0 criteria are applicable to all types of gliomas and can serve as a guide in clinical practice. |

| It is essential to know the histological type of the tumour, the treatments applied, and the timing of follow-up. |

| The baseline MRI for subsequent radiological follow-up will be the post-radiotherapy MRI (if not treated with radiotherapy, the baseline MRI will be the post-operative MRI or the MRI prior to the start of treatment). |

| In radiological follow-up of gliomas, it is not enough to use the immediately previous images for comparison: we have to use the baseline MRI or the MRI with the best tumour response (in cases of SD, PR or CR, we have to compare with the baseline MRI; in suspected DP, we have to compare with the MRI with the best tumour response). |

| GB: assessing contrast-enhancing tumour is sufficient to define the tumour response. |

| Other gliomas: assess both contrast-enhancing and non-enhancing tumour (disease T2/FLAIR). |

| Confirmatory MRI are only necessary in the first 12 weeks after RT; after this period, they are not required for glioblastomas and are optional for other glial tumours. |

| The appearance of a new lesion does not always mean progression: to be so, it has to be measurable (if confirmatory MRI is required, it should be included in the overall list of target lesions, and if not required, it can be established that there is progression). |

| The RANO 2.0 criteria are not exclusive of clinical and radiological criteria, so when there is any doubt about progression, early monitoring can always be performed regardless of the treatment phase or tumour type. |

CR: complete response; DP: disease progression; GB: glioblastoma; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PR: partial response; RANO: Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology Working Group; RT: radiotherapy; SD: stable disease.

The BTIP protocol recommendation remains in place without any update. It includes baseline and post-contrast T1-3D sequences, axial FLAIR-2D, axial diffusion and axial T2-2D, both for 1.5 T and 3 T scanners (Table 2).

Baseline magnetic resonance imagingThe bMRI is determined to be the post-RT MRI (approximately four weeks after completing RT) in newly diagnosed GB. If the patient is not given RT, the bMRI should be the pre-chemotherapy (pre-CT) MRI, performed as close to the start of treatment as possible (no more than 14 days), and not the immediate post-chemotherapy (post-CT) MRI. In recurrent gliomas, DP should be confirmed by evaluating studies from the last three months for GB and grade 4 IDHm gliomas, and from the last 12 months for grade 2 and 3 IDHm or other glial tumours. After confirmation of DP, the pre-CT MRI should be used as the bMRI.

Categorisation and response thresholdsThere are no changes in the categorisation of tumour responses. CR means the complete disappearance of measurable and non-measurable lesions. PR is a 50% reduction in m2D (65% m3D) compared to bMRI. DP is determined with a 25% increase in m2D (40% m3D) compared to the bMRI or the best response after the start of therapy if a reduction was demonstrated compared to the bMRI. It should be noted that these percentage changes are not necessarily in reference to the immediately previous scan when it was not the best response. Anything that does not meet the criteria for the rest of the tumour responses can be considered SD. Additionally, for IDHm and other non-GB gliomas, the MR category persists, consisting of a reduction in nCE tumour of 25%−50% in m2D (40%−65% m3D) with the CE tumour remaining stable. We have to bear in mind that the best radiological outcome for patients who do not meet the criteria for ML, such as gliomas with complete surgical resection, is SD.

Measurement- -

The main measurement is performed in m2D, being the sum of the products of the measurements of the different TL ([A × B = AB] + [C × D = CD]) the comparative value with respect to radiological control, and the m3D is left as optional, the comparative being the tumour volume.

- -

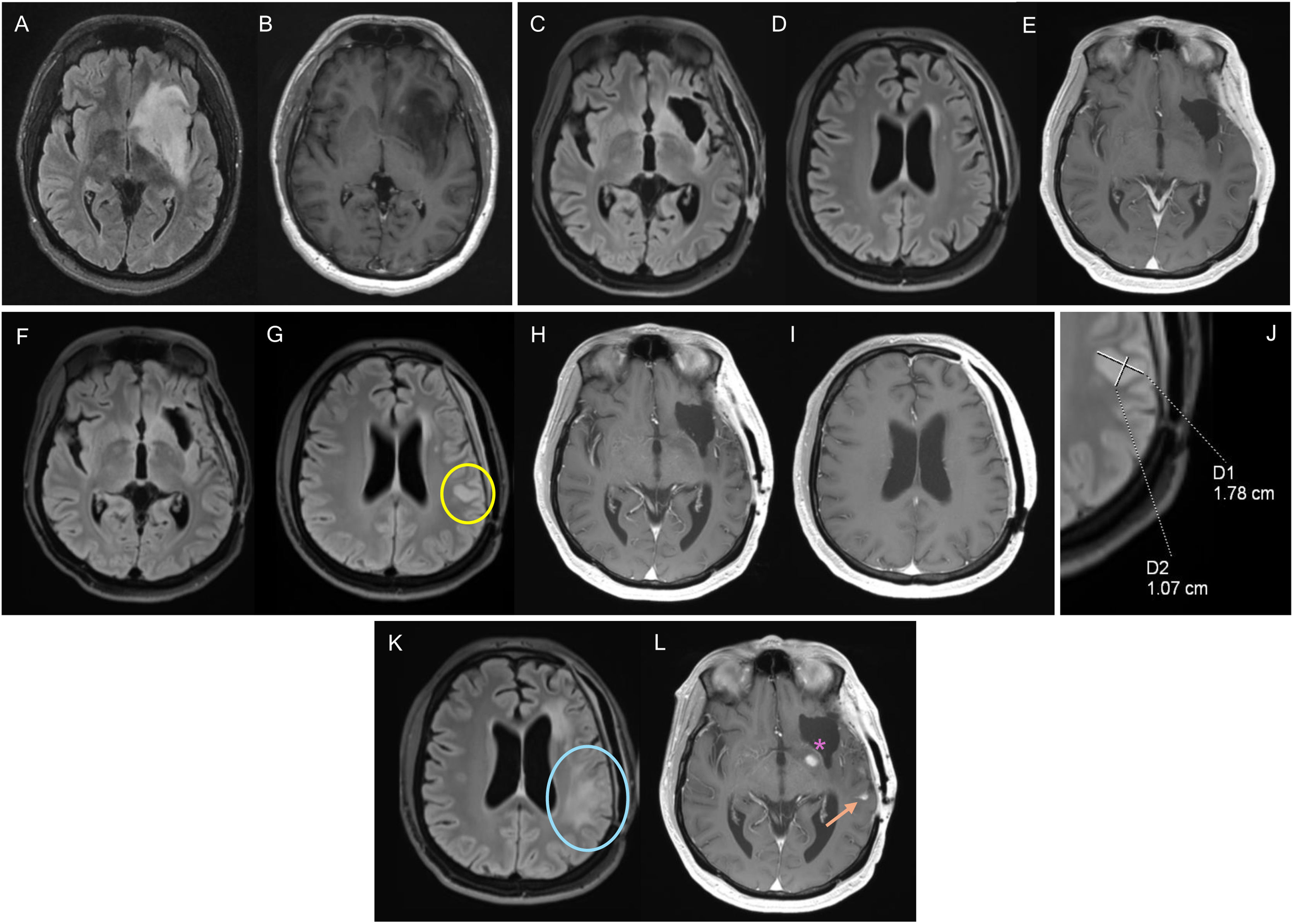

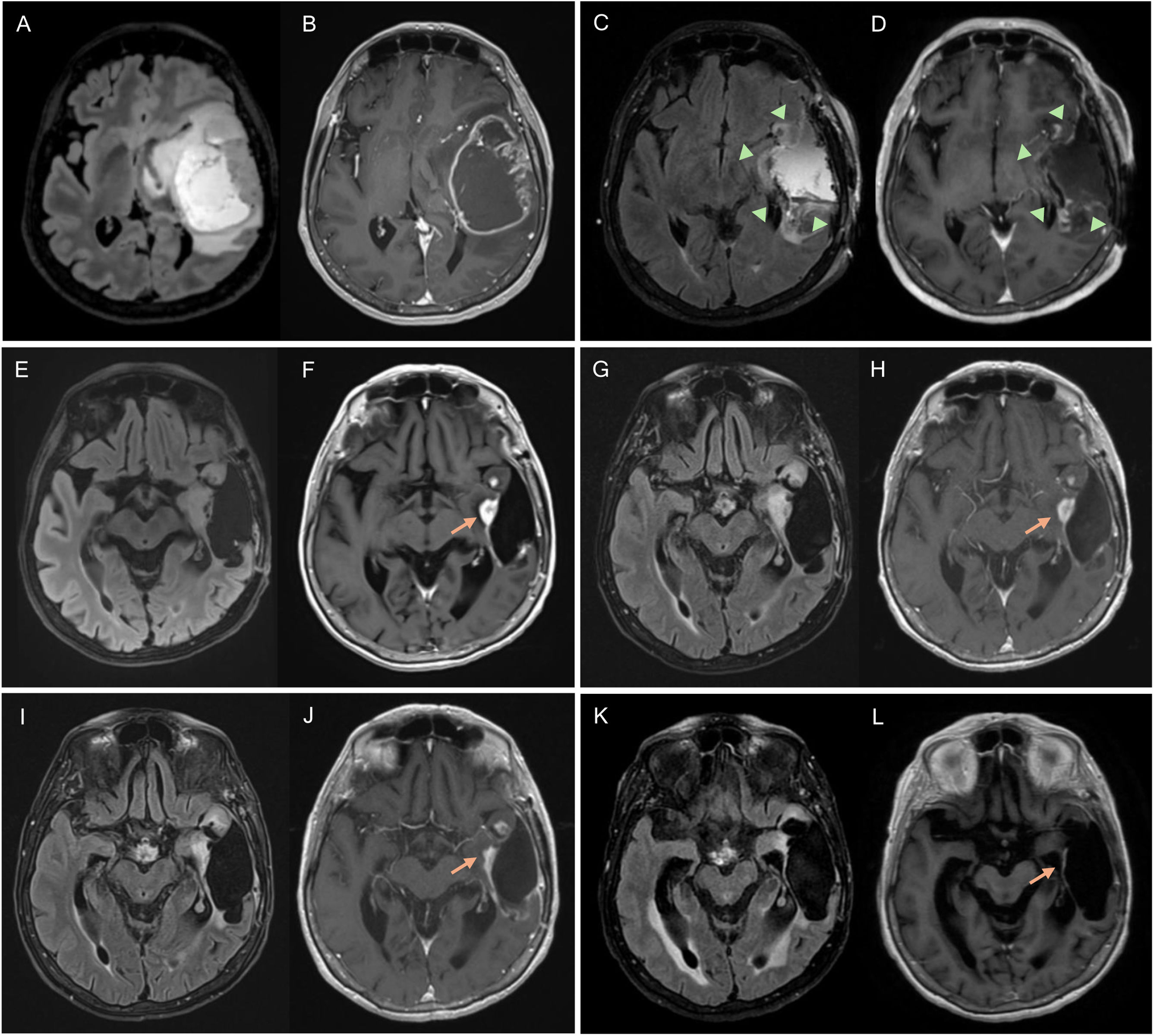

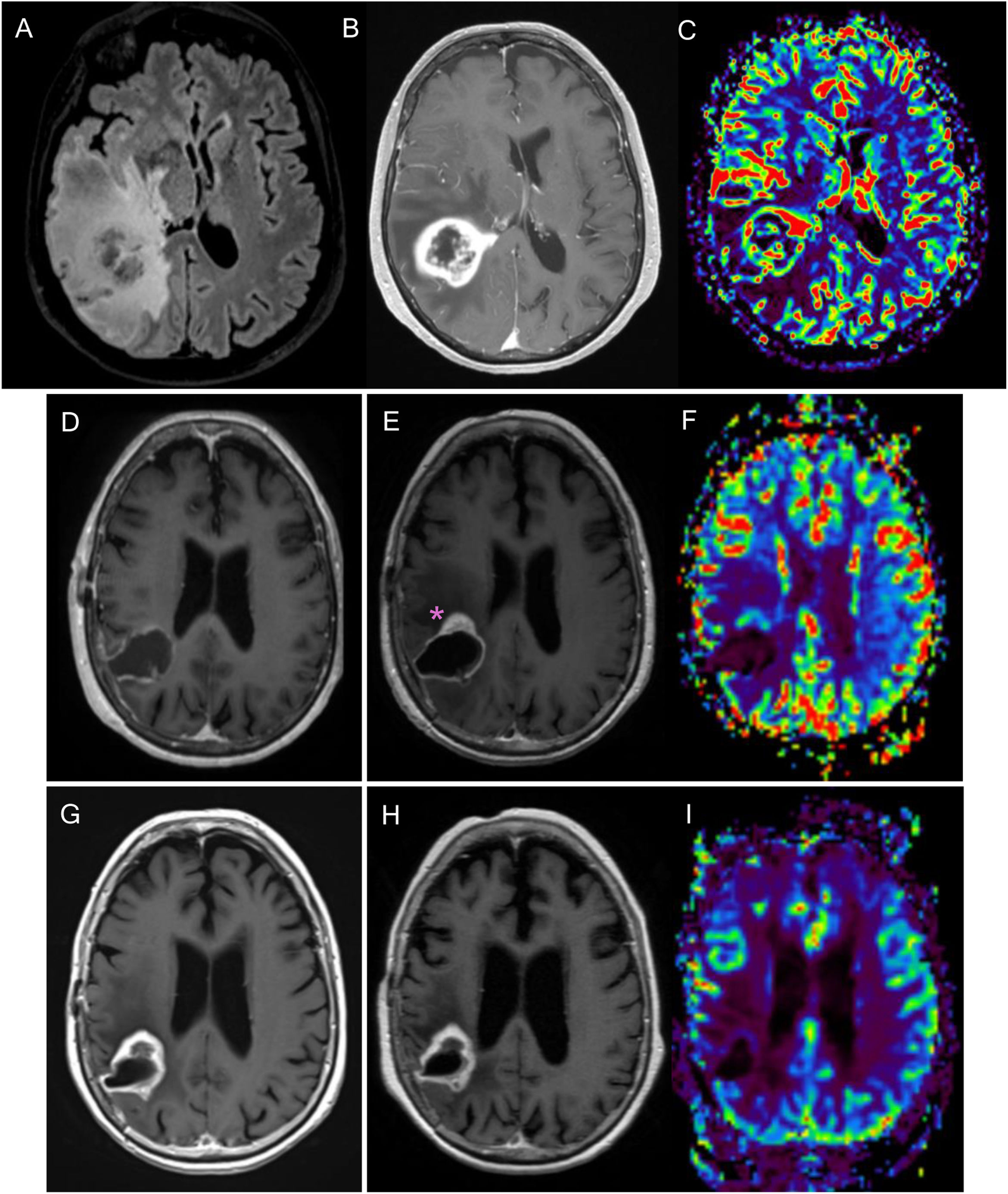

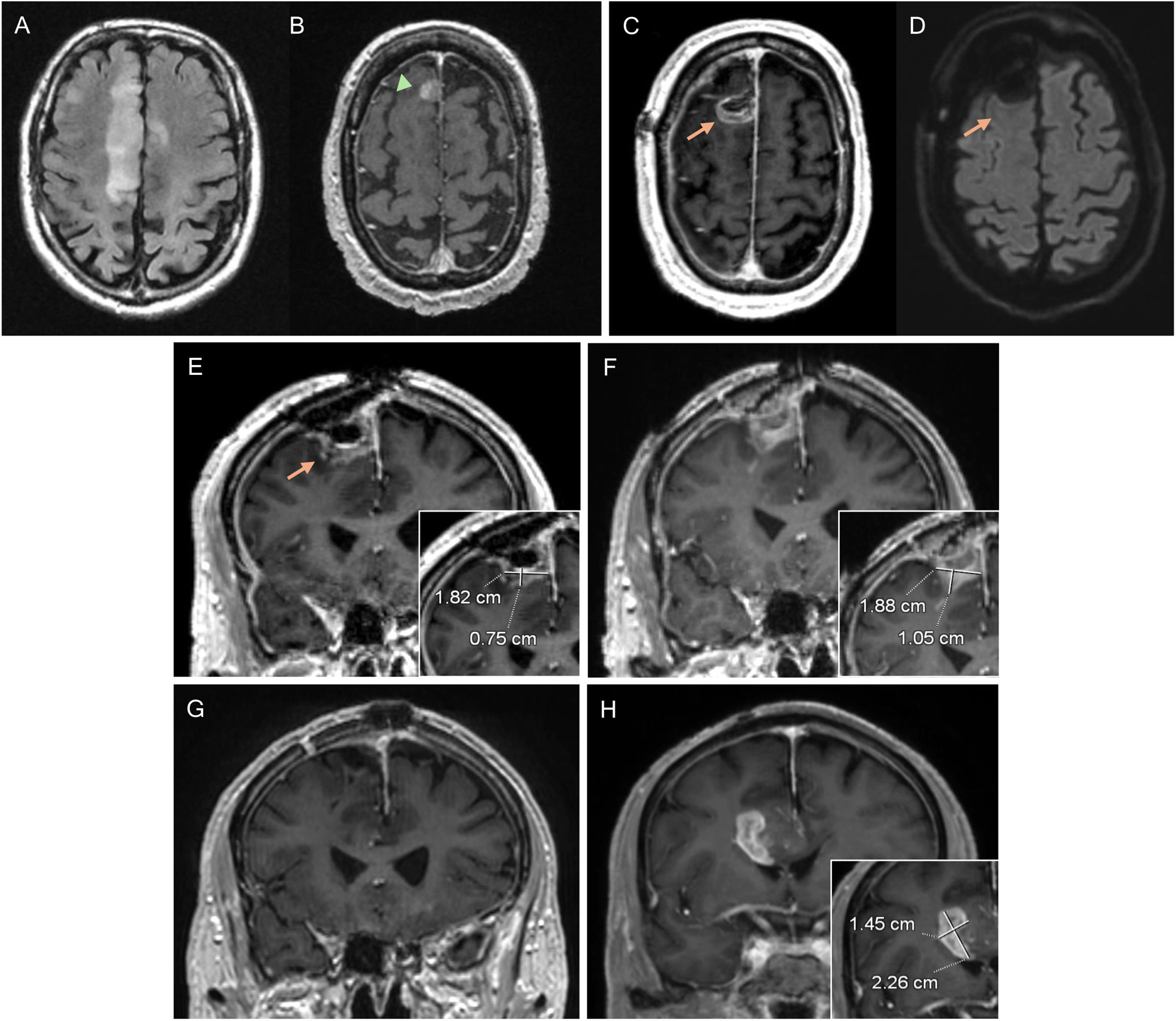

Lesions with well-defined margins which are at least 10 × 10 mm in m2D in any plane of space and visible in two or more sections, or at least 10 × 10 × 10 mm in m3D (Fig. 1) are considered to be ML. Lesions smaller than these measurements or with poorly defined margins are considered non-measurable disease, taking into account that postoperative cavities and the necrotic or cystic tumour component should not be included in the measurement. In the case of predominantly cystic lesions, only parietal thickening greater than 10 × 10 mm are considered measurable (Figs. 2 and 3) and the cystic component is not included in the measurement.

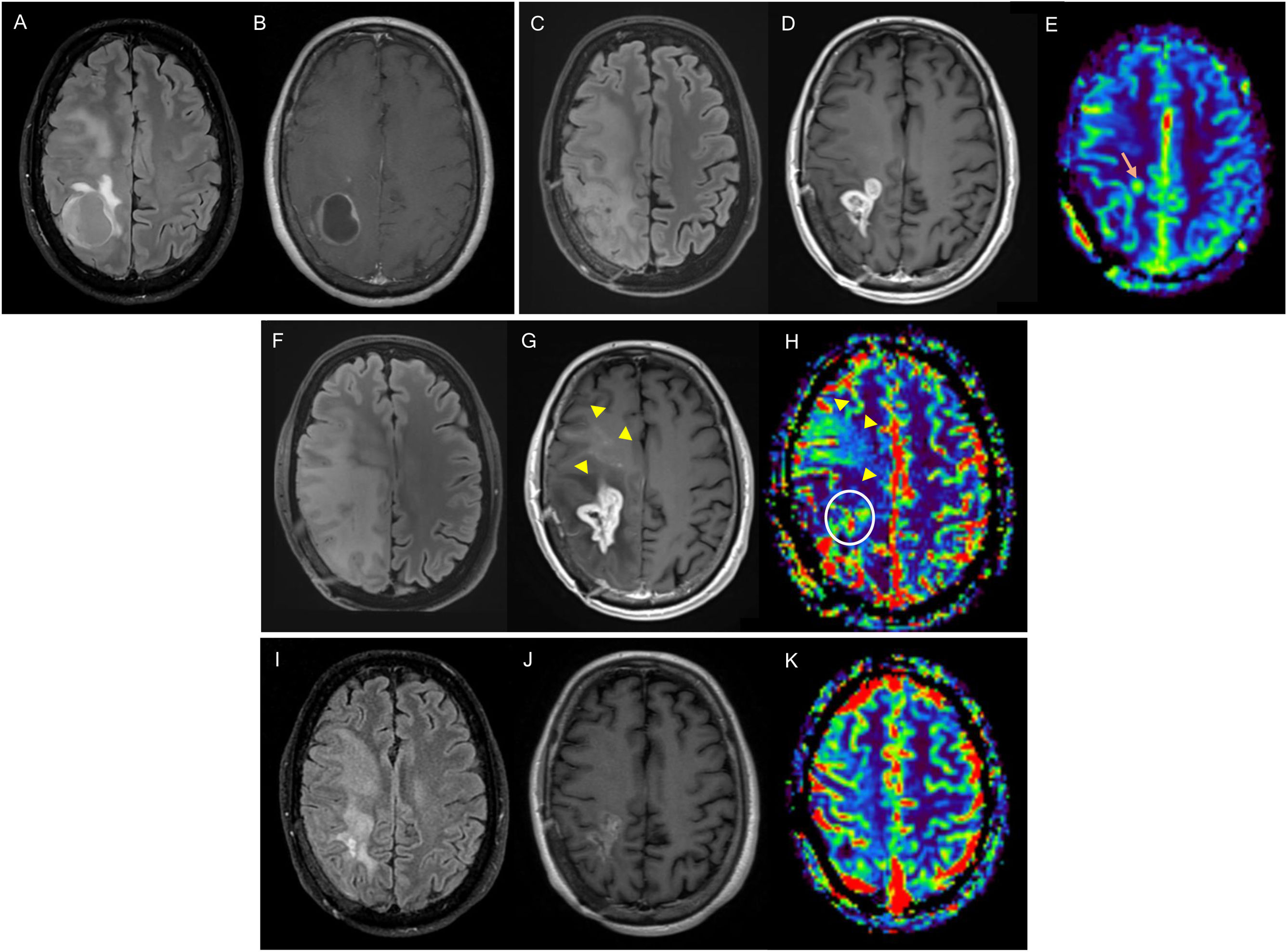

Figure 1.32-year-old man diagnosed with grade 4 IDH-mutant astrocytoma in the left frontal-insular region. Diagnostic MRI with FLAIR (A) and post-contrast T1-weighted (B) sequences. Baseline MRI corresponding to post-radiotherapy MRI, with altered pericavity signal in FLAIR (C), without parietal involvement (D), or contrast enhancement (E). After 20 months of follow-up, a repeat MRI (F–J) showed a new measurable non-enhancing lesion (yellow circle) in the parietal region, corresponding to disease progression. It was decided to perform yet another MRI (K,L), with disease progression confirmed after the increase in the non-enhancing lesion (blue circle) and the appearance of leptomeningeal dissemination (arrow). There is also a pericavity enhancement component (asterisk), but it is not measurable.

IDH: isocitrate dehydrogenase gene; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Figure 2.Glioblastoma in a 67-year-old woman in the left temporal-insular region. Follow-up assessment comparing FLAIR and T1-weighted post-contrast sequences from the diagnostic MRI (A, B), 48-h postoperative MRI (C, D) and post-radiotherapy MRI corresponding to the baseline MRI (E, F) to 1στ (G, H), 2νδ (I, J) and 3ρδ (K, L) follow-up MRI scans. Postoperative MRI 48 h later shows complete resection of the tumour-enhancing component (arrowheads). There is a measurable contrast-enhancing lesion in the baseline MRI (arrow) which, in the first repeat scan shows no changes (stable disease), in the second shows a reduction in size (partial response) and by the third, has disappeared (complete response). In subsequent follow-up checks, this last MRI will be the comparison MRI as it is the MRI with the best response.

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Figure 3.76-year-old woman diagnosed with right parietal glioblastoma demonstrated on MRI with FLAIR sequences, post-contrast T1 and CBV mapping in DSC perfusion (A–C). Complete resection of the contrast-enhancing component in the 24-h postoperative MRI (D). In the post-radiotherapy MRI (E,F), corresponding to the baseline MRI, there is a parietal nodular area of contrast enhancement (asterisk) without significant increase in volume in the CBV mapping of the DSC perfusion study (F). In the subsequent scans, six weeks (G) and 12 weeks post-concomitant RT and CT (H, I), a reduction in the size of the area of enhancement can be seen, without an increase in volume (I), findings related to pseudoprogression.

CBV: cerebral blood volume; DSC: dynamic magnetic susceptibility testing; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

- -

The measurement is performed on CE tumour (Fig. 2) and the measurement is re-incorporated in T2/FLAIR images of nCE tumour (Fig. 1). In GB it is recommended to measure only the CE tumour (Fig. 2) and in IDHm and other non-GB gliomas without CE tumour, to measure the nCE tumour (Fig. 1). In cases of GB without CE tumour (molecular GB), nCE tumour assessment is possible, until the appearance of measurable CE tumour. In the case of IDHm and other non-GB gliomas with a mixture of CE and nCE tumour, measurement of both components is possible.

- -

For the assessment of GB on treatment with antiangiogenic agents, in which PsR may exist, nCE tumour measurement is not recommended due to the difficulty in differentiating it from treatment-related changes.

In the case of tumours with multiple ML, up to three TL need to be identified, which should be CE or nCE tumour. If the clinical trial allows assessment of both CE and nCE tumour, up to four TL can be identified, with a maximum of two CE ML and two nCE ML. Other ML will be considered non-target and should be recorded, but not included in the calculation of tumour size. If in subsequent scans there are non-target lesions which increase in size, or non-measurable lesions which become ML (increase of at least 5 × 5 mm and total measurements of at least 10 × 10 mm in m2D or the corresponding in m3D), these lesions should be considered progression and included, without exceeding the limit of maximum TL. Additionally, if the initial TL have not changed in size in these scans, but other lesions that meet the target lesion criteria do, these other lesions should be redefined as TL.

New lesionsTo confirm a change in response category due to the appearance of new lesions, they would have to be ML and automatically mean DP (Figs. 1 and 4). Only if they occur in the period when conMRI is required (less than 12 weeks after the end of RT), new contrast-enhancing or non-enhancing lesions do not automatically mean DP, and we should expect to detect growth of such lesions in the conMRI and that the increase in size corresponds to DP thresholds (Fig. 5).

82-year-old man diagnosed with glioblastoma in the right superior frontal gyrus. Diagnostic MRI with FLAIR (A) and post-contrast T1 (B) sequences, showing a small anterior paramedian frontal focal enhancement (arrowhead). In the postoperative MRI (C–E) pericavity enhancement can be seen without alteration in diffusion (D), corresponding to residual tumour (arrows). A pre-radiotherapy MRI was performed, showing an increase in the size of the contrast-enhancement component, now measurable (F). In the post-radiotherapy MRI corresponding to the baseline MRI, the contrast-enhancement component (G) has disappeared. In the 1st follow-up MRI three months post-concomitant RT and CT (H), a new measurable lesion is evident, conclusive of disease progression.

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Diagnostic MRI with FLAIR (A) and post-contrast T1-weighted (B) sequences of glioblastoma in the right frontal-parietal region in a 39-year-old male. The post-radiotherapy MRI corresponding to the baseline MRI (C–E) shows a frontal-parietal area with altered FLAIR signal (C) and a contrast-enhancing component (D), with a slight focal increase in the volume in the CBV mapping (arrow) in the DSC perfusion study (E). In the 1st follow-up MRI three months post-concomitant RT and CT (F–H), disease progression is evident, with the finding of an increase of >25% in the contrast-enhancing component (G), which correlates with areas of increased perfusion volume (circle). Additionally, there is a non-measurable uptake component which also shows an increase in volume (arrowheads). Further follow-up MRI (I–K) after the start of bevacizumab shows antiangiogenic agent-related changes in the form of a reduction in the area of signal abnormalities in FLAIR sequences with improvement of the mass effect (I), reduction in the size of the area of contrast enhancement (J) and a tendency towards a return to normal of the volume map (K).

CBV: cerebral blood volume; DSC: dynamic susceptibility contrast magnetic resonance perfusion; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

The appearance of new, non-measurable lesions does not require a change in response category, but they should be monitored in subsequent scans.

The appearance of leptomeningeal dissemination visible on MRI, although not measurable, also suggests DP (Fig. 1).

Confirmatory magnetic resonance imaging: when should it be performed?- -

GB: If DP is suspected on MRI within 12 weeks after RT, conMRI should be performed, as the incidence of PsP is high in this period.32 This conMRI should be performed within four to eight weeks after the suspect MRI, where the changes should be referred to as preliminary progression (PreP). If DP is confirmed on conMRI, the PreP MRI will be the MRI diagnostic of DP (Fig. 5). However, if DP occurs outside the irradiation field, or there is confirmation by pathology, conMRI is not required. Beyond 12 weeks, conMRI would not be necessary (Fig. 4).

- -

IDHm and other non-GB gliomas: conMRI is also necessary in the first 12 weeks after RT if new areas of contrast enhancement or areas within the irradiated area suspicious for DP appear. Additionally, as the risk of PsP can extend beyond the first three months, conMRI is left as optional after this period.

- -

As PsP is directly related to contrast enhancement, when nCE progression is suspected in non-GB lesions, a conMRI would not be necessary (Fig. 1).

The new RANO-2.0 criteria represent an improvement over the radiological response criteria, but we have to bear in mind that they are intended for use in clinical trials. In the clinical setting, they should be considered as a guide to assist in the follow-up of patients with gliomas, but they should not be applied strictly. The goal of trials is to assess the efficacy of drugs while minimising bias, but preventing the continuation or discontinuation of treatment does not always result in better benefits for the patient. This is why the assessment of tumour response using RANO-2.0 always needs to be integrated with clinical and radiological criteria, the time course of the disease, and the views of the different specialists in multidisciplinary committees. We have listed below some points to consider when monitoring tumours radiologically in clinical settings.

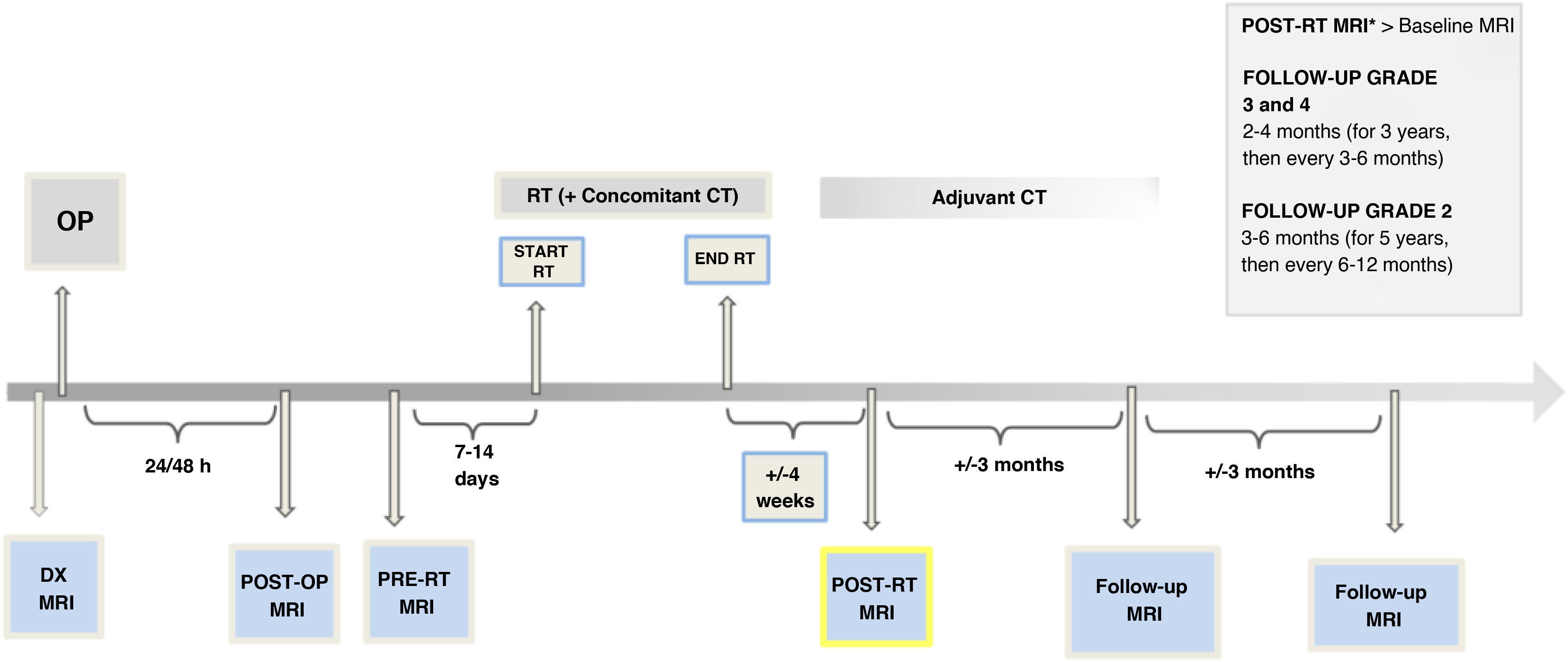

Timeline for performing magnetic resonance imaging in radiological follow-upThe RANO-2.0 criteria do not directly suggest a time frame for MRI follow-up. Although there is no absolute consensus, there are recommendations in clinical guidelines regarding the intervals between follow-up MRI scans:

- -

In grade 2 gliomas, perform checks every three to six months for the first five years and subsequently every six to 12 months.47,48

- -

In grade 3 and 4 gliomas, perform the first follow-up at two to eight weeks after RT, then scan every two to four months (for three years) and then every three to six months.47,48

All of this provided there are no clinical or radiological considerations which require more frequent monitoring (generally monthly) or that monitoring be extended.

In addition, a post-op MRI should be performed within 24−48 h after surgery, in order to assess residual tumour and possible complications.48

One thing to be considered is performing an MRI one to two weeks before starting RT (pre-RT MRI). This is necessary in most clinical trials and also recommended in international guidelines for its prognostic role and help in delimiting the irradiation area.49 Several studies have shown GB tumour growth between surgery and starting RT in around 40% of cases50,51 (Fig. 4), being more likely in patients with partial resections. A pre-RT MRI could therefore also reduce PsP diagnoses, particularly in cases with a delay in the start of treatment.

One of the limitations of this approach to postoperative follow-up is the availability of MRI in the clinical setting, but this pre-RT MRI can be performed with a simplified protocol that includes only 3D FLAIR and T1-3D sequences without and with contrast (Table 2).

A timetable for radiological follow-up is shown in Fig. 6.

Magnetic resonance imaging protocolThe BTIP protocol recommended by RANO-2.048 is a minimal protocol which has not been updated since 2015 and in which additional sequences could be included.

Structural sequences such as T2* or susceptibility studies should be considered in tumour assessment. These sequences are widely used in the clinical setting. They make it possible to identify intratumoral susceptibility signals, which correlate with the areas of neovascularisation in the case of tumour recurrence,52 and to assess RT-induced microangiopathic lesions.40

In terms of advanced MRI sequences, apart from diffusion, as in the previous versions of the RANO criteria, RANO-2.0 continues not to include them or to consider them for determining radiological response.14 They are widely used in the clinical setting, particularly diffusion and perfusion, and to a lesser extent, spectroscopy,53,54 helping to differentiate between tumour growth and post-treatment changes.9,30

There are numerous studies in the literature on the use of the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map to differentiate between DP and post-treatment changes,12,55 and even to predict treatment response. In second lines of treatment, survival is improved in relapsed tumours with low ADC with surgery, while those with high ADC have a better prognosis with the use of bevacizumab.56

Dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC) magnetic resonance perfusion has proved to be useful in differentiating between post-treatment changes and tumour recurrence, with relative volume being the most consistent parameter13 (Figs. 3 and 5). A consensus of technical and post-processing parameters for DSC perfusion was recently published57 which could be included within the BTIP.

A protocol adapted to the BTIP is proposed, including sequences for use in clinical practice (Table 2).

Other aspects to consider in clinical application- -

Histological confirmation of DP. Although RAN0-2.0 states that DP can be determined by histological analysis, it also recognises the limited reliability in differentiating DP from post-treatment changes, with lack of agreement between pathologists,58 quite apart from the difficulty of repeating surgery and availability of histological samples. At certain stages of disease progression, tumour cells and post-treatment changes may coexist, making a pathology-based diagnosis difficult. Furthermore, the detection of tumour cells does not mean the treatment is not being or may not continue to be effective. This underlines the difficulty in post-treatment assessment of patients with tumours, as even the technique considered the gold standard has its weak points.

- -

DP on bMRI. In RANO-2.0, bMRI is the initial test for monitoring the disease's progress, but they do not specify what course of action to take if there is suspected DP on this scan. If the bMRI corresponds to an MRI prior to the start of treatment (pre-Trt MRI) with suspected DP, as there is no risk of PsP, the DP is assumed to be real. If it is a post-RT MRI, if the changes are outside the irradiation area they also suggest actual DP. However, if the changes are within the irradiation area, the conMRI should be performed (Fig. 5). The dilemma of PsP therefore has to be kept in mind both in the bMRI and subsequent MRI scans in the first 12 weeks after RT. Finally, if the post-RT MRI does not show any suspicion of DP, the next check-up would be in three months, by which time the PsP dilemma has disappeared for GB (Fig. 4). It should be noted that in IDHm, PsP may exist beyond 12 weeks after RT,59 so an MRI after this period will depend on clinical and radiological criteria.

- -

Molecular GB. Follow-up of molecular GB is challenging due to the low-grade radiological pattern, despite having molecular features of GB. Initially, they may not have CE tumour and monitoring could therefore be based on nCE tumour. In subsequent follow-ups, the appearance of a CE ML would correspond to DP according to RANO-2.0. This is an endpoint in clinical trials, but not in clinical practice, so follow-up should be maintained. As it is a radiological pattern and not a molecular change, follow-up after this DP should be based on CE (Fig. 4), and not on nCE, since it has been shown that the assessment of nCE in GB provides no benefit.46 If the initial DP is secondary to the growth of nCE without evidence of CE, follow-up should be based on nCE until CE appears.

- -

PsR in GB. For the assessment of tumour response to treatment with antiangiogenic agents and suspected PsR, RANO-2.0 does not recommend the measurement of nCE. Additionally, since a high percentage of these patients end up developing CE,36 it is recommended that further MRI scans continue to be performed until the new CE is identified. However, in clinical practice, a delay in the diagnosis of DP may delay a possible change in therapy or intervention, and in the case of an increase in nCE, when it is clearly conclusive that it corresponds to a tumour in T2/FLAIR sequences and not post-treatment changes, it could be automatically interpreted as DP, without having to wait for the appearance of new CE in subsequent scans.

- -

Subependymal spread. Compared to leptomeningeal metastasis, which is a criterion for DP, RANO-2.0 does not mention the need to assess subependymal disease. There are studies that indicate that the two are equivalent in terms of prognosis,60 and this should also therefore be taken into account during the reading of follow-up MRI scans in the clinical setting.

- -

Follow-up uncertainties. Although RANO-2.0 establishes specific measurement and response limits, sometimes these limits are not so clear (lesions at the size limit or percentage changes at response categorisation limits, which may or may not determine DP). In these cases, the patient may continue treatment and be reassessed at a new MRI interval, with the multidisciplinary committee agreeing on closer clinical monitoring.

- -

Difficulties in the clinical setting. In clinical trials, all clinical and radiological information is well collected, but this is not always the case in clinical practice. This is important because for correct assessment of response monitoring, we need to know which MRI is the one showing the best response in cases of suspected DP, not necessarily the most recent, as well as what treatment stage the patient is in. Efforts have been made to create structured reports with more precise information, an interesting example being the Brain Tumor Reporting and Data System (BT-RADS),15 but there is still a long way to go in structuring the clinical, surgical and radiological information relevant for radiological follow-up.

The recent publication of the RANO-2.0 criteria provides a starting point for their implementation in clinical trials. Further analyses are required to determine their validity in this setting, as well as to determine whether their application in clinical practical is feasible. The utility of monitoring CE and nCE tumours in IDHm, or the utility of nCE tumours in molecular GB, and even whether this distinction in the response assessment in other non-GB and non-IDHm gliomas is necessary, remains to be seen. The inclusion and standardisation of advanced MRI techniques in BTIP is still pending and so it is hoped that future updates will take this into account. Other imaging tests such as positron emission tomography (PET)61 may also be considered, or the implementation of radiomic and artificial intelligence analyses,62,63 which have really come to the fore recently.

ConclusionsThe RANO-2.0 criteria are at last based on clinical validation data, making them more robust and reliable, encompassing all types of gliomas and the different treatments available. Although these criteria are designed to be applied in clinical trials, knowledge and understanding of them are crucial, as they can be of great help in clinical practice in the radiological assessment of patients with gliomas.

CRediT authorship contribution statement- 1

Responsible for the integrity of the study: C. Pineda Ibarra, S. González Ortiz.

- 2

Study conception: C. Pineda Ibarra, S. González Ortiz.

- 3

Article design: C. Pineda Ibarra, S. González Ortiz.

- 4

Data collection: C. Pineda Ibarra, S. González Ortiz.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: C. Pineda Ibarra, S. González Ortiz.

- 6

Statistical treatment: C. Pineda Ibarra, S. González Ortiz.

- 7

Literature search: C. Pineda Ibarra, S. González Ortiz.

- 8

Drafting of the article: C. Pineda Ibarra, S. González Ortiz.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: L. Oleaga Zufiria, I. Valduvieco Ruiz, E. Pineda Losada, T. Pujol Farré.

- 10

Approval of the final version: C. Pineda Ibarra, S. González Ortiz, L. Oleaga Zufiria, I. Valduvieco Ruiz, E. Pineda Losada, T. Pujol Farré.

This project received no specific grants from public-sector agencies, commercial-sector agencies or non-profit organisations.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

To all members and patients of the Hospital Clinic Neuro-Oncology Committee.