Psychometrics is a simple, intuitive approach used in educational research and in multiple-choice questionnaires. Since 2009, the competitive examination through which access to residency programs in Spain is determined (MIR) has included questions related to radiological images. The objective of this paper is to show the results of the psychometric analysis of these questions with the aim of comparing their degree of difficulty, discriminative capacity, and internal structure with respect to those of the other questions on the examination.

Material and methodsWe analyzed all questions on the examination since 2009, classifying them as clinical cases with and without radiological images, clinical cases with and without non-radiological images, multiple choice questions, and negative questions. We used classical test theory and item response theory to assess the difficulty and degree of discrimination of the questions.

ResultsOf 225 questions, between 11% and 15% of the questions included in the examinations were associated with images. The questions associated with radiological images were more difficult (corrected difficulty index, 0.51) and had worse discriminative capacity. The increased difficulty of radiological questions was associated with worse discriminative capacity, especially if the clinical information provided was inadequate or if the clinical information was contrary to the radiological concept or if there had never been any questions about the concept in previoous MIR examinations.

ConclusionsTo equalize the standards of the MIR examination, it is necessary to maintain an appropriate structure in devising radiology questions, with terms from the clinical context, appropriate use of distracters, and a lower level of difficulty, which could be achieved by using radiological images with typical radiological findings.

La psicometría es una técnica sencilla e intuitiva que se utiliza en el campo de la docencia y en el de los cuestionarios de respuesta múltiple. El examen MIR incluye desde el año 2009 preguntas asociadas a imagen radiológica. El objetivo de este trabajo es mostrar los resultados del análisis psicométrico de estas preguntas con objeto de comparar el grado de dificultad, la capacidad de discriminación y la estructura interna respecto al resto de preguntas.

Material y métodosSe seleccionaron todas las preguntas del examen desde el año 2009 y se clasificaron en casos clínicos sin y con imagen radiológica, casos clínicos con imagen no radiológica, preguntas test y preguntas negativas. Se utilizó la teoría clásica de test y la teoría de respuesta al ítem para valorar la dificultad y el grado de discriminación de las preguntas.

ResultadosSobre 225 preguntas, los exámenes incluyen entre un 11% y un 15% de preguntas asociadas a imágenes. Las preguntas asociadas a imagen radiológica son más difíciles (grado de dificultad corregida [IDc] 0,51), con una menor capacidad de discriminación. El aumento de la dificultad de la pregunta radiológica se relaciona con una menor discriminación, sobre todo si la información clínica no es adecuada, o es contraria al concepto radiológico, o el concepto nunca ha sido preguntado a lo largo de la historia del MIR.

ConclusionesPara poder igualar los estándares del examen MIR, es necesario mantener una adecuada estructura en la confección de las preguntas de radiología, en términos de entorno clínico, un adecuado uso de distractores y un menor nivel de dificultad, que se puede lograr mediante el uso de imágenes con hallazgos radiológicos típicos.

Psychometrics is a simple, intuitive tool that can be used in the field of teaching. Applications of psychometrics are wide-ranging. They are used in education research,1 in which they are associated with competencies in teaching and learning processes through electronic media2 and are included in the new technologies that have been incorporated into teacher training, having been cited since the 1990s.3 They are also used in current studies on new digital technologies as educational resources in a university context.4,5

Psychometric techniques have been used for multiple-choice exams to assess question quality, to analyse internal coherence, to identify their discriminatory capacity in relation to levels of knowledge and to ascertain their difficulty. In recent years, we have used these psychometric techniques and adjusted them based on electronic analysis of responses in order to implement student training during preparation for the medical residency exam in Spain. Our objective is to achieve the highest level of quality in exam preparation tests, detect training gaps and find concepts that we should emphasise in this post-university training.

The Médico Interno Residente (MIR) medical residency exam seeks to rank aspirants from highest to lowest exam scores and grade point averages to allow for an ordered selection of the placements offered each year for specialised healthcare training in Spain.6,7

MIR exam sessions have been held every year since 1978 by the Spanish Ministry of Health and the Spanish Ministry of Education on the same day and at the same time throughout Spain. The MIR exam consists of 225 multiple-choice questions, plus 10 reserve multiple-choice questions on any field of medicine. It must be completed within 5 h. Each correct answer adds three points to the exam taker's total score, and each incorrect answer subtracts one point from that score. The mark that the exam taker achieves on the exam (90% of the final mark) and the assessment of the exam taker's grade point average or academic record (10% of the final mark in the last session) are combined to rank all aspirants from highest to lowest total score. Those who achieve scores above the cut-off mark, the minimum mark required for access to a specialised healthcare training placement, will be in a position to choose the specialisation and the hospital where they will do their MIR training.7–12

The exam has included questions associated with one or more images since the 2009 MIR exam (hereinafter, we shall refer to the exam as the Ministry does, i.e. by the year in which the exam is announced, not the year in which the exam is taken). These images may be radiological (referring to any images from diagnostic imaging tests) or non-radiological (referring to any other images from medical records, histology imaging, diagrams, spirometry imaging, electrocardiograms, etc.).13

In this study, we show a sample of our work on psychometric analysis of questions associated with radiological images and contrast them with the rest of the questions on the MIR exam so as to compare their levels of difficulty and discriminatory capacities and confirm the usefulness of the MIR exam as an instrument for measuring the extent of the medical knowledge of those who take it.

Material and methodsWe selected questions from the 2009 MIR exam session through the 2017 MIR exam session. These totalled 2025 questions. We chose these sessions because they covered all the MIR exams with questions associated with images (in the early 1980s, electrocardiograms were occasionally featured on MIR exams, but this practice stopped, most likely due to the poor printing quality available at that time). We did not include questions associated with radiology concepts if they were not associated with a radiological image.

Multiple-choice questions were classified according to the following sub-types for analysis:13,14

- 1

Case reports without an image: multiple-choice questions that featured lengthy wording rather than an image and proposed a differential diagnosis of a disease, a treatment, and/or the diagnostic and therapeutic management of a patient according to data from his or her medical record, clinical examination and laboratory and complementary test results. If they included information on imaging tests, they did so as a description in the text of the question.

- 2

Case reports with a non-radiological image: case report-type questions with wording related to a non-radiological image or diagram.

- 3

Case reports with a radiological image: case report-type questions associated with an imaging test.

- 4

Negative questions: questions that asked the exam taker to identify the incorrect response among a number of possible responses.

- 5

Multiple-choice questions: all other questions that were briefly worded and considered to be neither case reports nor negative questions. Normally, these questions were direct and asked the exam taker to choose the correct response among the responses offered.

Psychometrics is the discipline that deals with all the methods, techniques and theories involved in measuring and quantifying the psychological variables of the human psyche. Psychometrics encompasses test theory and construction as well as other valid, reliable measurement procedures. It includes the preparation and application of statistical procedures that determine whether or not a test is valid for measuring a previously defined psychological variable.

Several psychometric models are adapted for assessing responses to multiple-choice questions. They all have in common the fact that they mathematically link latent (non-observable) characteristics of test questions and the subjects who answer them in order to develop accurate models of each subject in relation to each question, depending on their level of knowledge. To evaluate the MIR exam, we used two mathematical models: classical test theory and item response theory (IRT). These variables have been used and confirmed for this exam in previous studies.13–18

Classical test theory: this is a way of measuring the difficulty, discriminatory capacity and quality of questions according to the number of people answering them and their level of knowledge, expressed by the final grade that they achieve on the entire test to be assessed.19–22 The following tools are used as part of this model:

- 1

Calculation of difficulty index (DI): this represents the percentage of exam takers who answered the question correctly versus incorrectly. Thus, questions can be divided up as follows:

- a)

Easy: those answered correctly 66% or more of the sample.

- b)

Moderate: those answered correctly by 33%–66% of the sample.

- c)

Difficult: those answered correctly by less than 33% of the sample.

- a)

- 2

Corrected difficulty index (cDI): this represents the percentage of students who gave the right answer to a question, corrected for the likelihood of guessing the right answer. Thus, on a test with three incorrect answers and one correct answer (where each correct answer adds one point), there is a 25% chance of answering correctly by guessing. Since response error accounts for a value of −0.33 points, this value for a question can range from −0.33 to 1. It is a more precise way of studying the difficulty of a question with a penalty for answering incorrectly, such as those on the MIR exam. In this study, we classified questions according to the following scale:

- a)

Very difficult: those with values from −0.33 to 0.

- b)

Difficult: those with values from 0 to 0.33.

- c)

Optimal: those with values from 0.33 to 0.66.

- d)

Easy: those with values from 0.66 to 0.80.

- e)

Very easy: those with values from 0.80 to 1.

- 3

Calculation of the discrimination index: this is the correlation between exam takers' scores on the entire test and their scores on a given test question. As the MIR exam is a single test, exam takers with higher scores on the exam are believed to have higher levels of general medical knowledge, and exam takers with lower scores are believed to have lower levels of said knowledge. To calculate this value, for the purpose of this study, we used the point biserial correlation coefficient (rpb), which seeks to measure questions' discriminatory quality. The higher the rpb value, the stronger the relationship between achieving a high score on the test and having answered that particular question correctly. Using this correlation coefficient, we were able to classify questions' discriminatory capacity as follows:

- a)

Excellent: for values obtained from the rpb greater than or equal to 0.40.

- b)

Good: for values obtained greater than or equal to 0.30 and less than 0.40.

- c)

Fair: for values obtained greater than or equal to 0.20 and less than 0.30.

- d)

Poor: for values obtained greater than or equal to 0 and less than 0.20.

- e)

Terrible: for cases with a negative rpb.

Item response theory (IRT): this psychometric theory is used to predict how exam takers would answer questions according to their level of knowledge. To this end, several probability models have been proposed which estimate the likelihood that an individual is capable of answering a particular question correctly. This study used a model known as the two-parameter logistic (2-PL) model to determine the relationship between the likelihood of an exam taker answering a question correctly and their level of medical knowledge demonstrated in the MIR exam as a whole. According to the proposed model, the likelihood of correctly answering a question depends, on the one hand, on the parameters of each question (difficulty and discriminatory capacity) and, on the other hand, the subject's level of knowledge. Two values are to be considered in this model:23–28

- 1

IRT difficulty: this represents a question's difficulty score corrected for an exam taker's level of knowledge. Its value is normally −4 to +4. A higher value indicates that the question is more difficult, and a lower value indicates that the question is easier.

- 2

IRT discrimination (DC-R): this represents the discriminatory capacity of a question corrected for the level of knowledge of the exam takers. According to the scale proposed by the authors in a previous study,15 questions can be classified in a manner similar that used for rpb values:

- a)

Excellent: for values obtained from the discrimination coefficient greater than 1.

- b)

Good: for values obtained from the discrimination coefficient greater than 0.70 and less than or equal to 1.

- c)

Fair: for values obtained from the discrimination coefficient greater than 0.40 and less than or equal to 0.70.

- d)

Poor: for values obtained from the discrimination coefficient greater than or equal to 0 and less than 0.40.

- e)

Terrible: for negative values obtained from the discrimination coefficient.

- a)

Item response theory variables can be used to generate a curve for the probability of answering a given test question correctly depending on the knowledge of the exam taker. This shows not only the question's degree of discrimination, but also the level of knowledge at which maximum discrimination is achieved.

These psychometric variables have been used to assess all the question types that we have used to classify MIR exam questions. Questions associated with a radiological image were compared to all the other types of question on the exam in relation to the psychometric variables described.

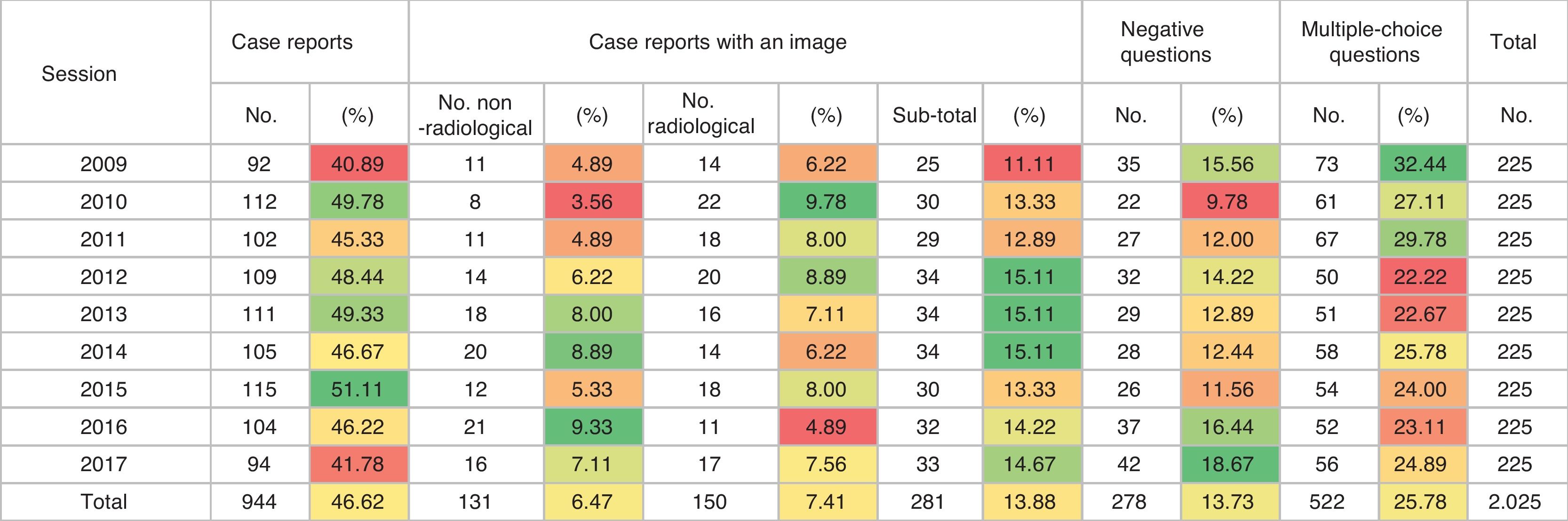

ResultsSince 2009, MIR exam questions have usually consisted of approximately 45% case reports, 15% negative questions, 25% multiple-choice questions and 15% questions associated with an image. Half of the questions associated with an image were radiological questions; all the others were questions associated with a non-radiological image (pathology images, clinical photographs, spirometry images, electrocardiograms, etc.). The number of questions with a radiological image ranged from 11 to 22. The exam with the largest number questions related to radiological images was the 2010 MIR exam (9.78% of all questions). The exam with the smallest number of questions related to radiological images was the 2016 MIR exam (4.89% of all questions) (Fig. 1).

Proportions of case reports, case reports with an image (radiological or non-radiological), negative questions and multiple-choice questions from the 2009 to 2017 MIR exam sessions. The colours indicate the distribution of the proportion of questions. Red indicates the years with the lowest volume, yellow indicates the years with an intermediate volume and green indicates the years with the highest volume.

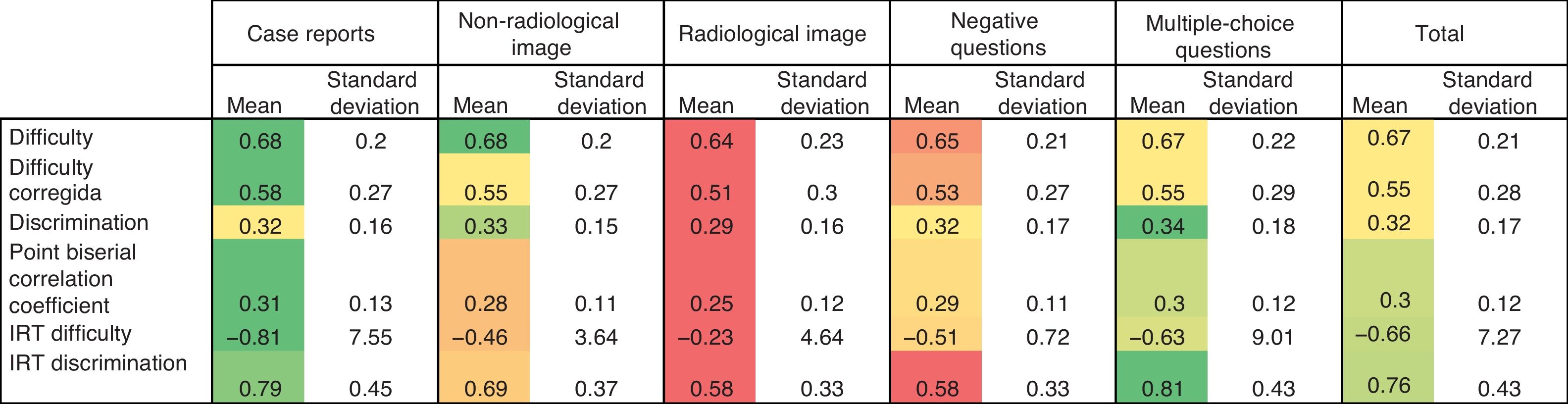

On average, questions on the MIR exam with a radiological image have a higher difficulty value, with an average probability of answering correctly of 64% (Fig. 2). Considering a difficulty value of 33%–66% to be optimal, the most difficult exam for this type of question was the 2014 MIR exam session, with an average rate of correct answers of 39.8%, and the easiest exams were the 2012 and 2017 MIR exam sessions, with rates of correct answers exceeding 71%. Regarding questions with a non-radiological image, the MIR exam session with the highest average difficulty was the 2015 MIR exam, and the one with the lowest average difficulty was the 2011 MIR exam. Questions with a radiological image were more difficult across all MIR exam sessions, save for the 2010, 2012 and 2015 sessions.

Mean value and standard deviation for the following variables: difficulty, difficulty index corrected for random chance, discrimination index, point biserial correlation coefficient, difficulty score according to item response theory (IRT) and discrimination index according to item response theory for the questions from the 2009 to 2017 MIR exam sessions. The colour scale shows the values for the variables. The values in red are the lowest, the values in yellow are intermediate and the values in green are the highest. Note that the questions associated with an image are the ones with the most difficulty and the least discriminatory capacity.

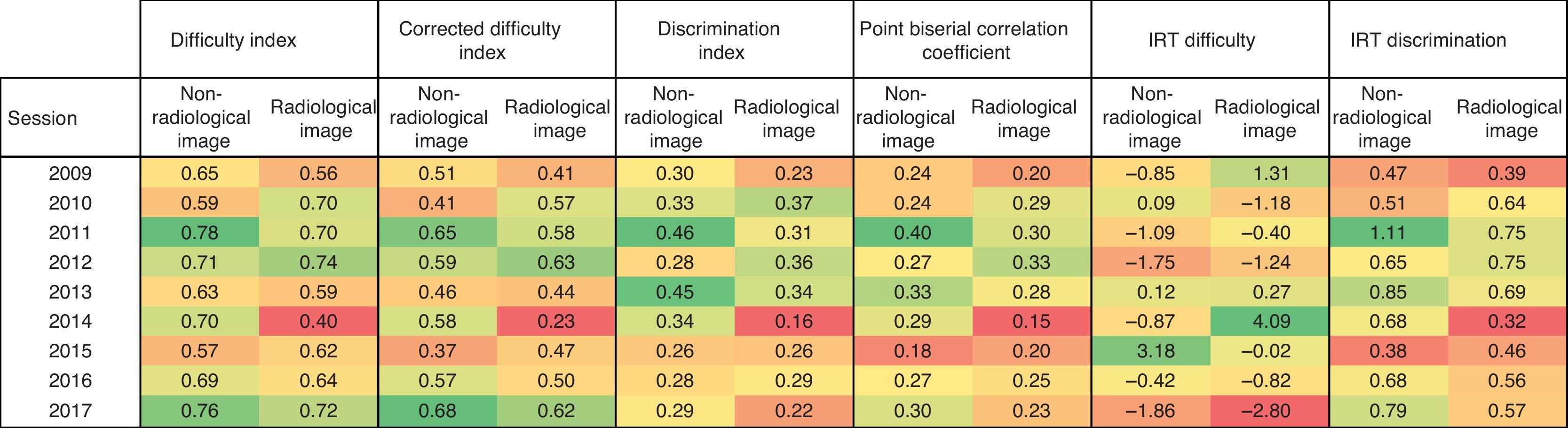

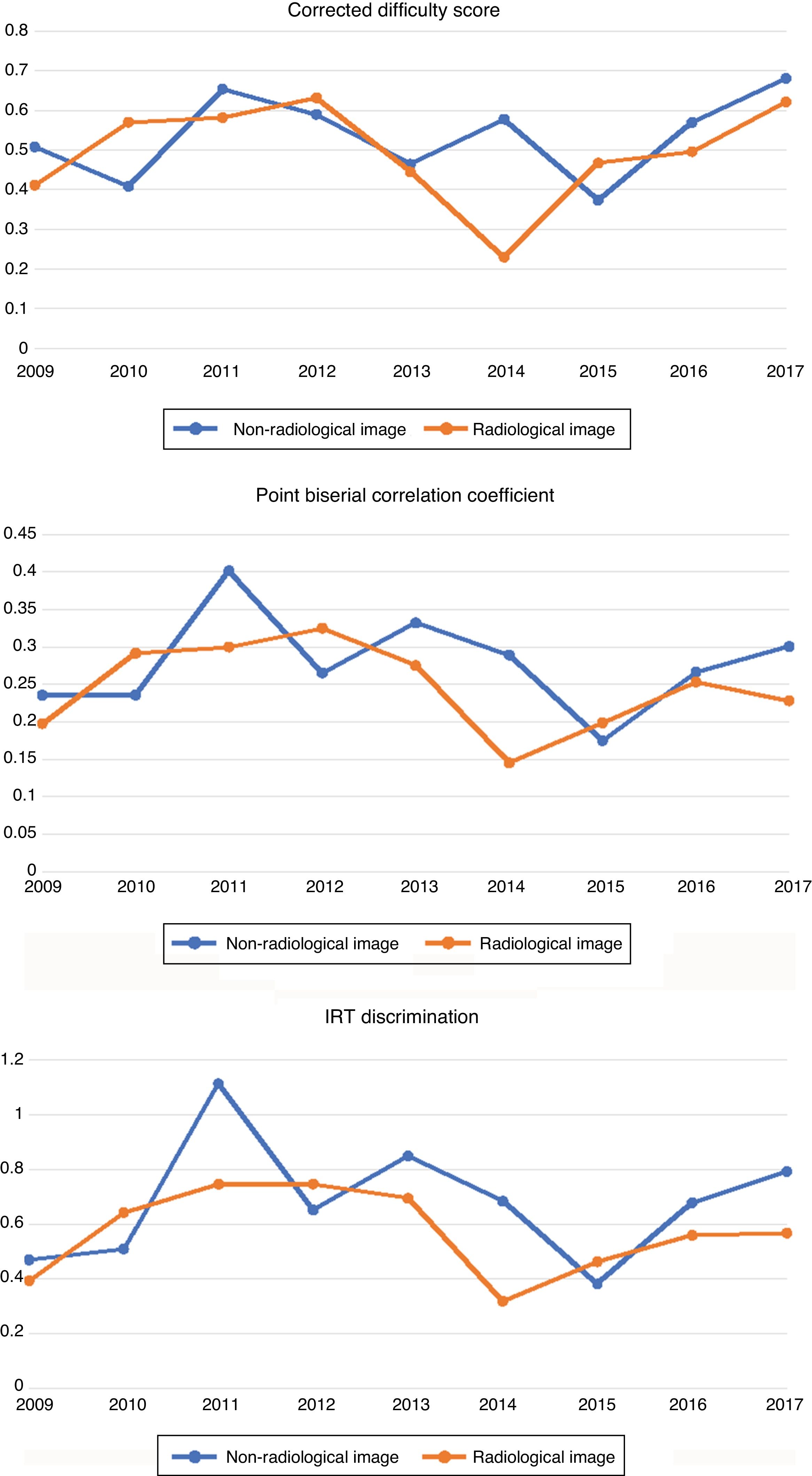

Regarding average difficulty score values corrected for random chance, questions with a radiological image were, on average, the most difficult ones on the MIR exam, with a mean value of 0.51 (Fig. 2). Considering a difficulty value of 0.33–0.66 to be optimal, the most difficult exam for this type of question was the 2014 MIR exam session, with an average value of 0.23, and the easiest exams were the 2012 and 2017 MIR exam sessions, with an average value exceeding 0.62. Regarding questions with a non-radiological image, the MIR exam session with the highest level of difficulty was the 2015 MIR exam session, and the one with the lowest level of difficulty was the 2011 MIR exam session. Questions with a radiological image were more difficult across all MIR exam sessions, save for the 2010, 2012 and 2015 MIR exam sessions. Figs. 3 and 4 compare the average corrected difficulty score for questions with a radiological image and questions with a non-radiological image across the time series analysed.

Changes over time in difficulty index, corrected difficulty index, discrimination index, point biserial correlation coefficient and difficulty and discrimination according to item response theory (IRT) for questions associated with an image, radiological or non-radiological, across MIR exam sessions. The colour scale indicates the years with the lowest values (in red) and the years with higher values.

Comparison of changes over time in the main psychometric parameters between questions associated with a radiological image and questions associated with a non-radiological image. Difficulty score corrected for random chance: the higher this is, the more difficult it is to answer the question correctly. Point biserial correlation coefficient: this represents a measure of the quality of the questions whereby questions are deemed good or excellent if they exceed 0.30. IRT discrimination (DC-R): this represents the discriminatory capacity of a question for the different levels of knowledge among the exam takers. A question is considered good if it exceeds 0.70 and excellent if it exceeds 1.

One measure of questions' discrimination was the rpb; questions with an rpb value exceeding 0.30 were classified as good or excellent. On the MIR exam, this correlation coefficient's average values for multiple-choice questions, negative questions and case reports were approximately 0.30 (good discrimination) (Fig. 2), whereas its average values for questions with a radiological image were 0.25 (fair discrimination). In the 2011 and 2012 MIR exam sessions, the average value for this correlation coefficient exceeded 0.30, corresponding to years with easier questions. Questions associated with a non-radiological image had average values for this discrimination index higher than those of questions associated with a radiological image, except in the 2010, 2012 and 2015 MIR sessions (Figs. 3 and 4).

Regarding the discriminatory capacity of the questions using the item response theory metric, we considered a question to be good if this metric had a value over 0.70 and excellent if this metric had a value over 1. The MIR exam had good discriminatory capacity, exceeding 0.70 on average. The questions with the highest average IRT discrimination value were multiple-choice questions and case reports. The questions with the worst average IRT discrimination were questions with a radiological image and negative questions, at 0.58 (Fig. 2). Across time, the years with the highest average IRT discrimination values for questions related to a radiological image were the 2011 and 2012 MIR exam sessions, exceeding 0.74. Questions associated with a non-radiological image had average IRT discrimination values higher than those of questions associated with a radiological image, except in the 2010, 2012 and 2015 MIR sessions (Figs. 3 and 4).

Statistical analysis of frequencies of multiple-choice options in questions associated with a radiological image pointed to a significant preference for the second and third responses among the options shown; the third response was correct for nearly 50% of questions.

DiscussionPsychometrics is an objective technique with an extensive basis in science that has systematically demonstrated its value for analysing evaluation methods applied to a group of individual test-takers.17,21,23 Multiple-choice exams such as the MIR exam can be analysed in a simplified manner using 'classic test theory'20 and 'item response theory' (IRT)'15 in order to determine the probability of answering a question correctly or incorrectly depending on an individual's knowledge.

On a multiple-choice exam, a student's knowledge is represented by their total score on the test. Therefore, the main limitation of these techniques on an exam like the MIR exam is the fact that it is a single measure, at a single moment, of an individual's knowledge, which can give rise to external validity errors.15,20 Ideally, the individual would be assessed multiple times over the course of several days to decrease these errors. To partly counteract this limitation, the Ministry provides for joint assessment of an individual's exam and grade point average. The weight of the latter has varied across MIR exam sessions.

Moreover, MIR exam preparation centres operate in such a way that a concept that is asked about in one session is subsequently incorporated into the study materials; therefore, if that concept were to be asked about again in a subsequent session, the psychometric values for the question would change significantly for the subsequent session. Ever since questions with radiological and non-radiological images made their début on the MIR exam, all preparation centres have included questions associated with an image in their databases, giving more or less importance to the subject at their discretion and featuring or not featuring instructors specialising in radiology.

Overall, the MIR exams from the period analysed (2009–2017) represented a well-structured multiple-choice test, with a difficulty index corrected for random chance (cDI) at an optimal level (0.55); its questions have a good mean discriminatory capacity as measured by the rpb (0.30) and it has a good discriminatory capacity as measured by the DC-R (0.76). Similar values have been obtained in previous studies through analysis of a single session15,20 or a number of sessions overall.14

When questions are divided into sub-groups based on wording, the questions with the greatest quality and discriminatory capacity are the ones based on case reports (those that deal with the medical record of a simulated patient, and those that ask about their diagnosis and/or treatment) as well as the direct multiple-choice questions that ask about a medical concept (both had a DC-R exceeding 0.75 and an rpb exceeding 0.30). Questions with negative wording, in which responses contained three true statements and one false one that had to be identified, had a lower average discriminatory capacity.

Since the 2009 session, 11%–15% of questions on MIR exams have been related to one or more images, whether radiological or non-radiological (histopathology images, electrocardiograms, spirometry images, clinical photographs, etc.). These two sub-groups of questions have in common that they require the exam taker to take more time to interpret and answer them, as they call for a combination of reading a question and analysing an associated image printed on paper. In theory, adding questions associated with an image to the exam is intended to more closely align the questions on the exam with routine clinical practice.

Psychometric study of questions related to a radiological image indicated that, on average, they are more difficult (cDI 0.51, maintaining an optimal level), but that they have, on average, a lower discriminatory capacity on the exam (rpb 0.25 and CD-R 0.60, both corresponding on their respective scales to a fair discriminatory capacity). On average, questions related to non-radiological images were slightly easier and they had a slightly higher discriminatory capacity than questions related to radiological images, but a lower discriminatory capacity than case reports and direct multiple-choice questions.

When we analysed changes in psychometric values for questions associated with a radiological image across the time series studied, we found that average discriminatory capacity increased in sessions in which the difficulty of the questions approximated the mean difficulty of the MIR exam (the 2010 and 2011 MIR exams) and that discriminatory capacity decreased in sessions with a significant increase in difficulty such as the 2014 MIR exam.

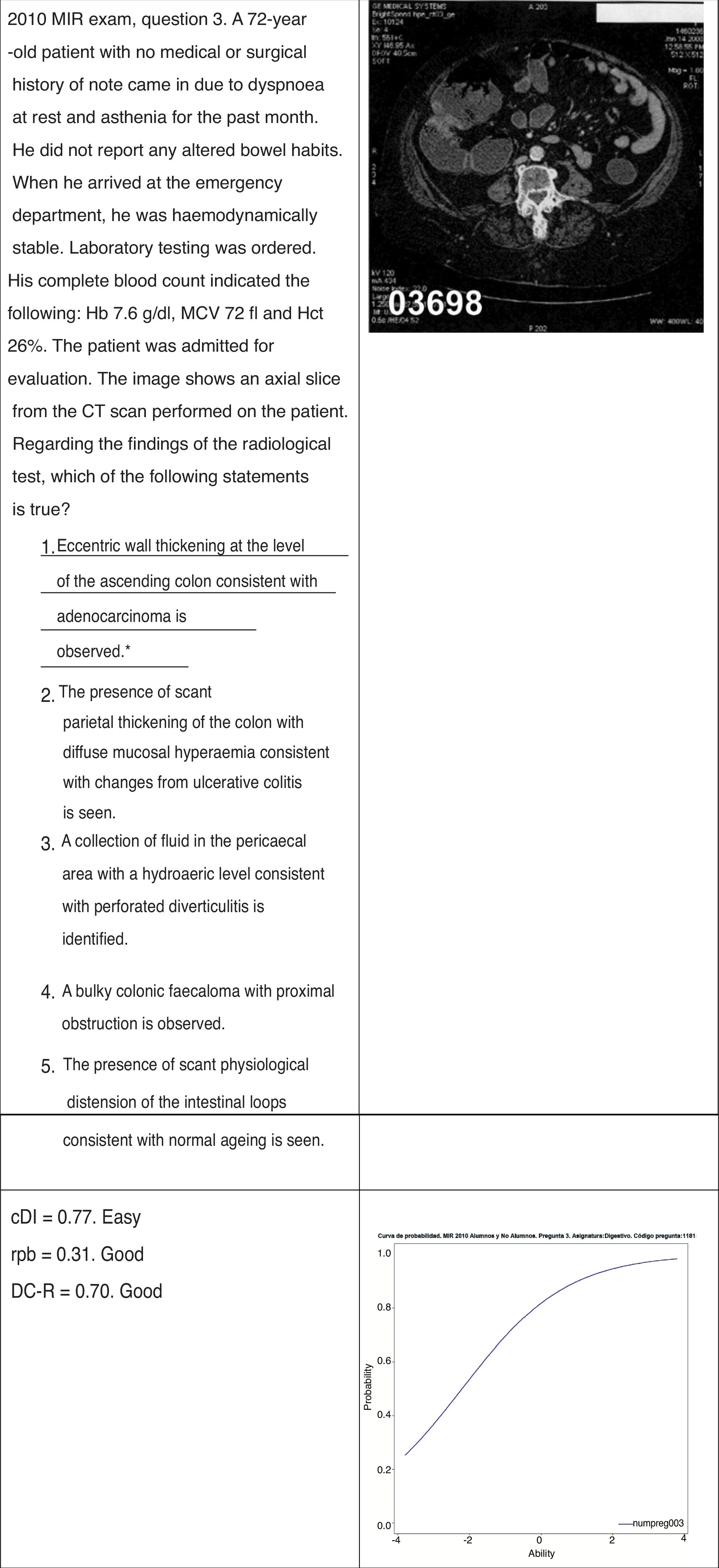

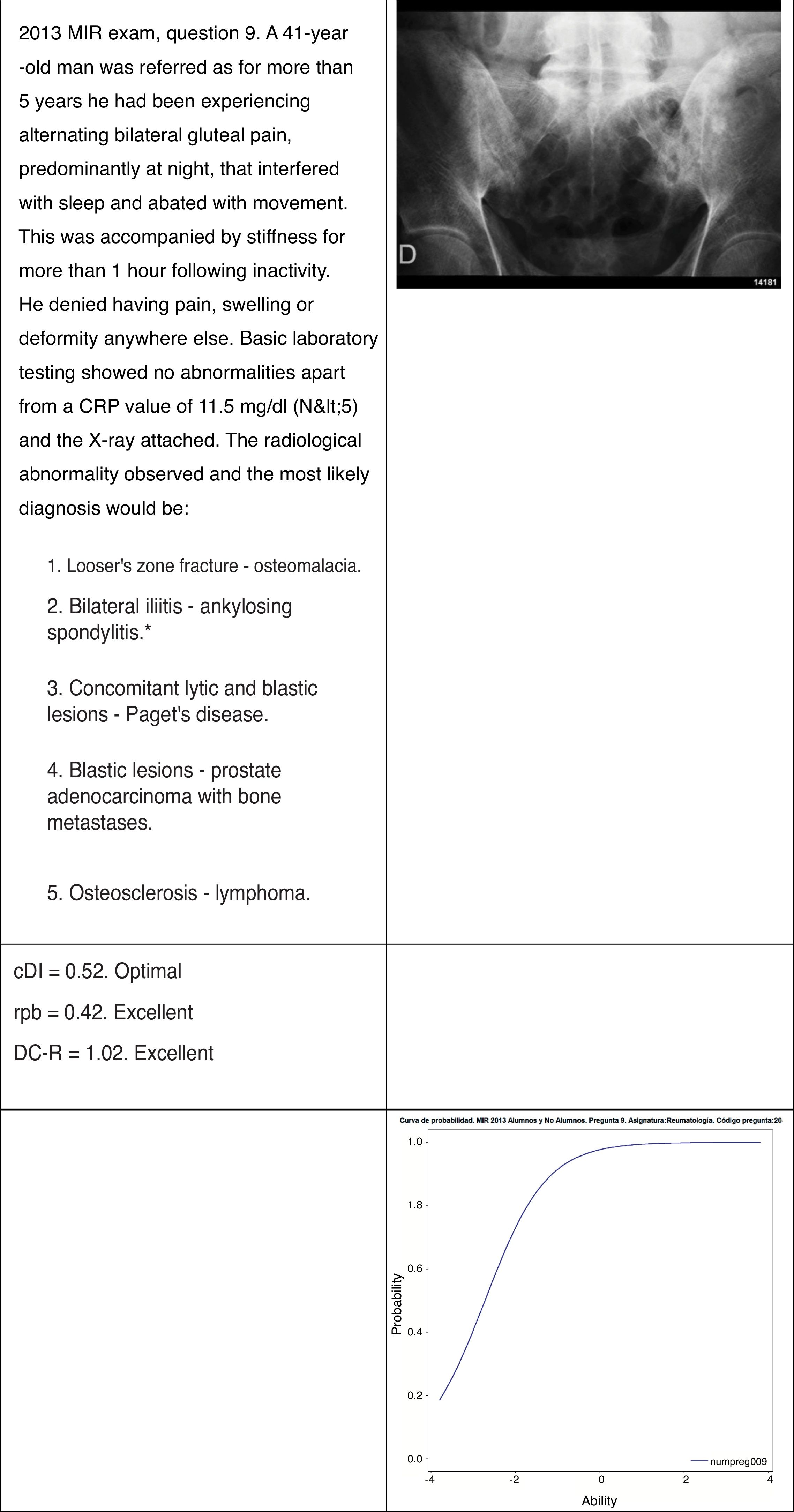

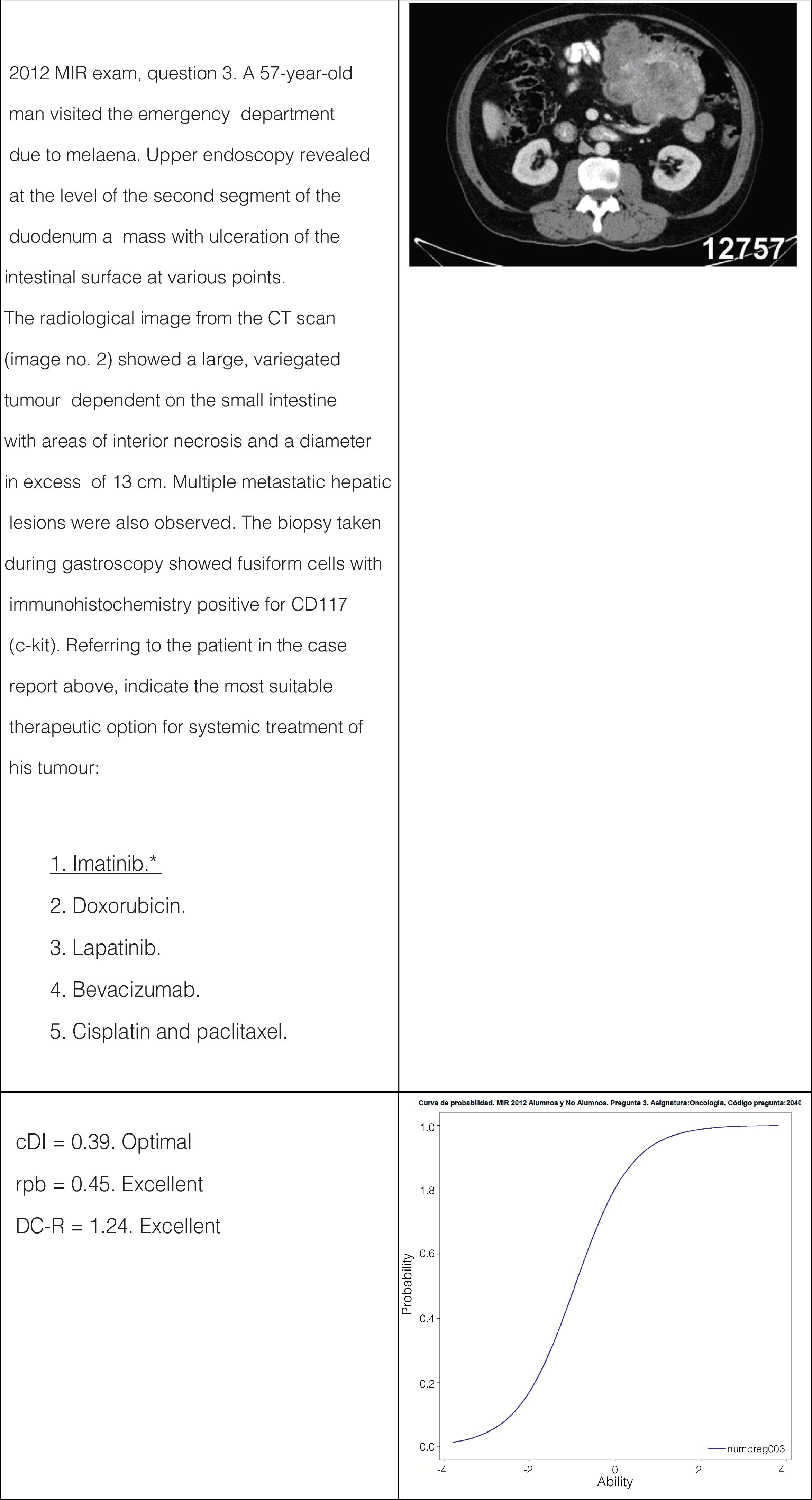

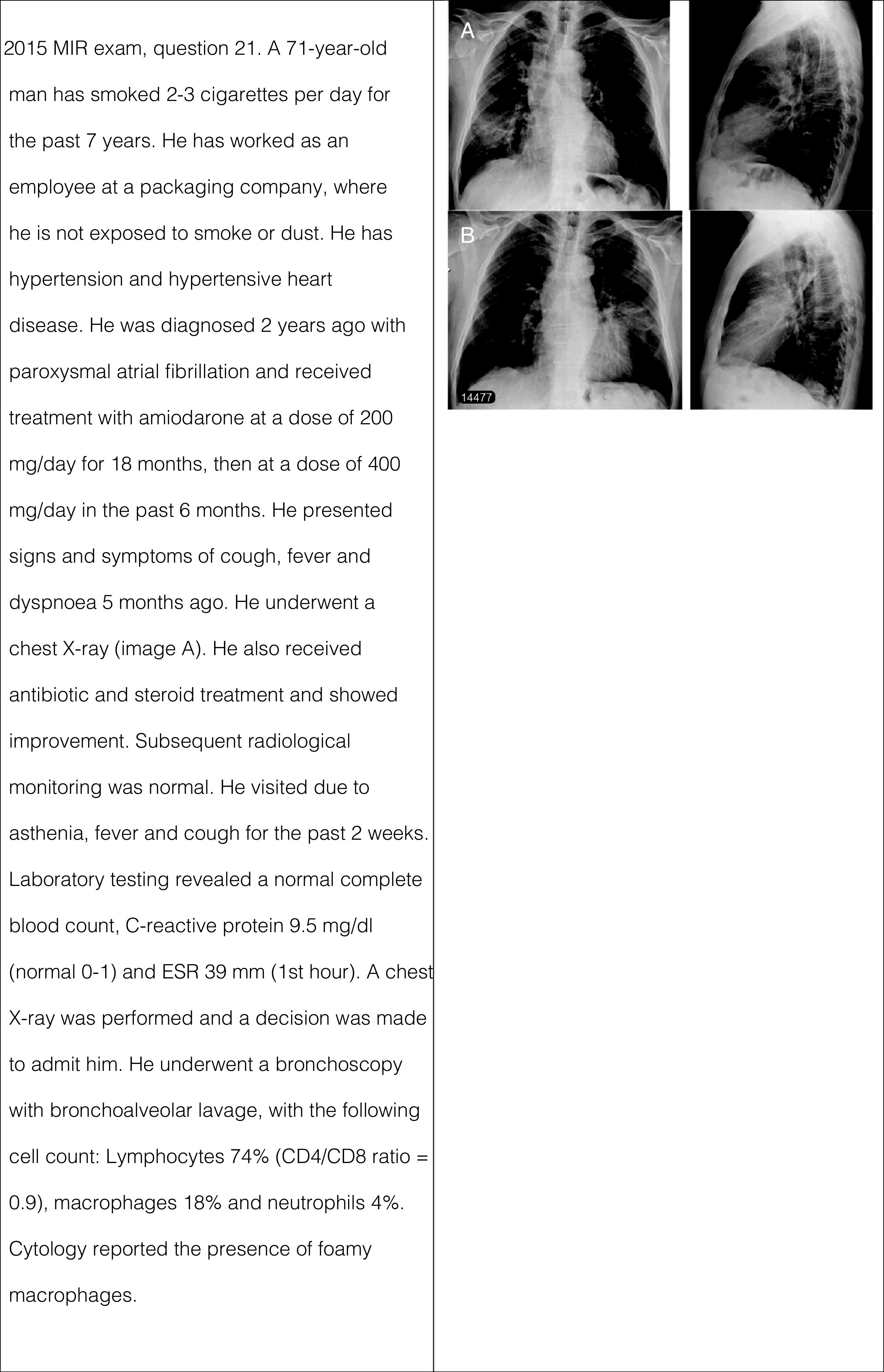

Individual analysis of questions showed that the following questions were more likely to be answered incorrectly by exam takers, and therefore more difficult: radiological questions in which the concept asked about represented the capacity to visualise a radiological finding without any associated clinical information; questions in which the radiological finding changed the response that could be inferred from the clinical information supplied; and questions in which the radiological finding was not a significant clinical concept (due to its rare or exceptional nature) or had never been asked about in the history of the MIR exam. These three factors caused a significant increase in the difficulty of the question, as well as a decrease in its discriminatory capacity, as they caused exam takers with a lower level of knowledge to have a higher probability of answering the question correctly than exam takers with a higher level of knowledge (Figs. 5–8).

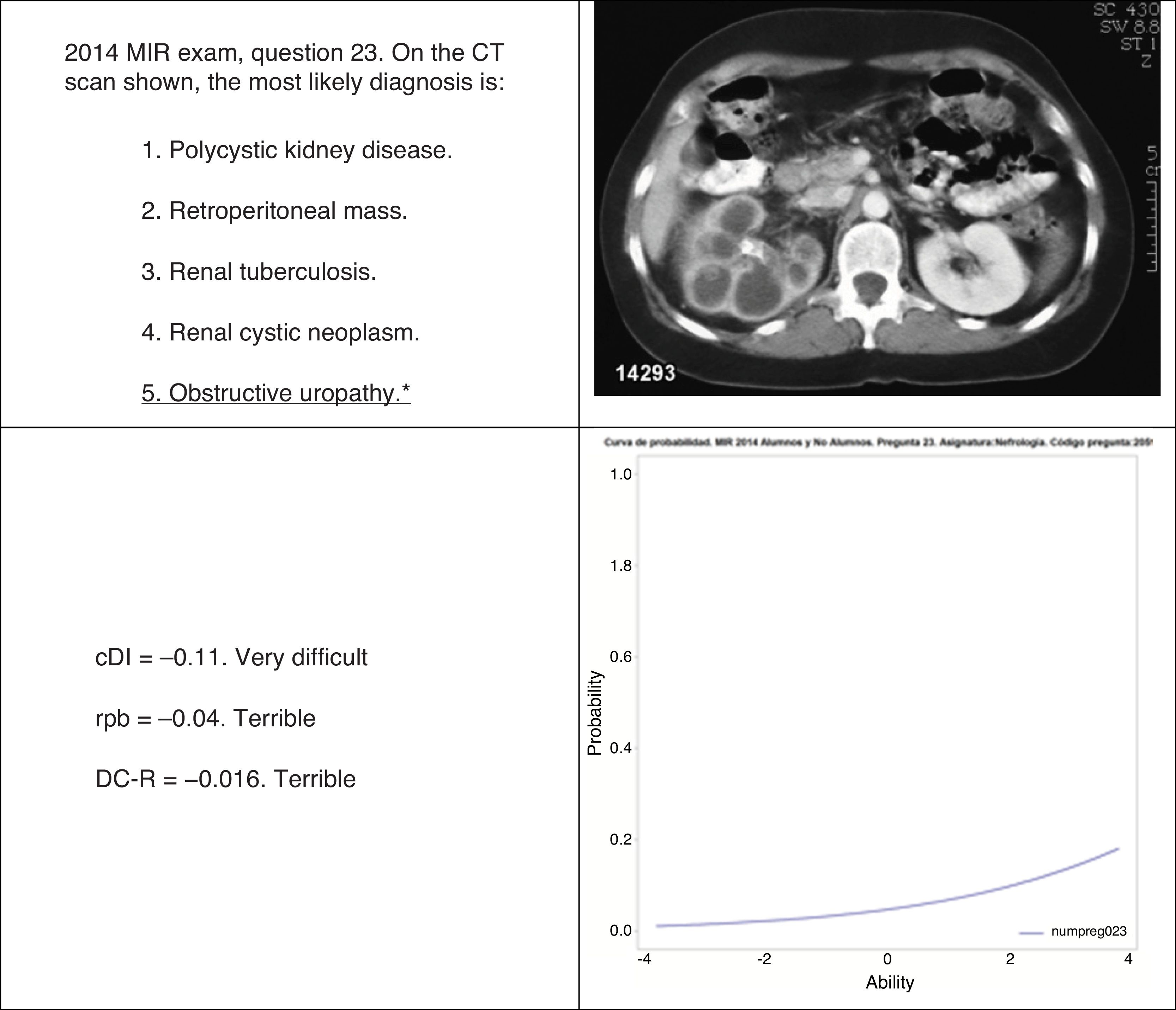

Example of a question with a high level of difficulty and a low level of discrimination. The question's discrimination qualifies as terrible. On the curve of probability of answering correctly, exam takers with the highest scores in the exam had a higher probability of answering the question correctly than students with low scores in the MIR exam, though the differences between the two groups were small. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis has a characteristic image with renal calculi plus abscesses and would probably have been a disease known to the exam takers as it has figured in previous exams. Furthermore, the exam takers would have been familiar with the image of obstructive renal lithiasis by computed tomography and ultrasound. Asking a question with no mention of clinical characteristics (renal colic) and with an image not typical of dilatation of the renal pelvis confused exam takers in both the strong group and the weak group. Attempting to increase the question's difficulty by decreasing the clinical information that it supplied and associating it with a non-characteristic image achieved the undesirable effect of decreasing the question's discriminatory capacity.

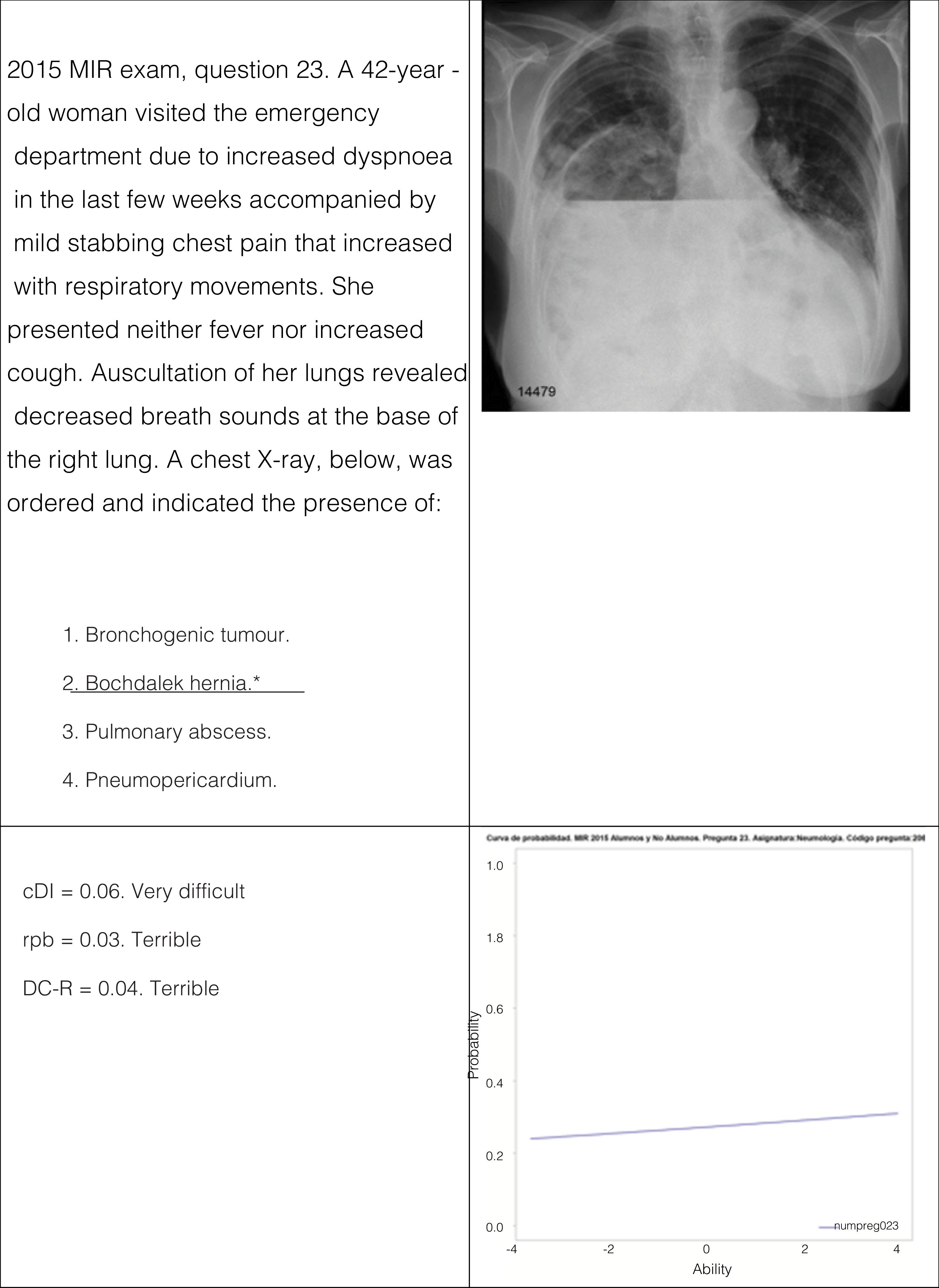

Example of a question in which a basic radiological concept was addressed (diaphragmatic hernia, Bochdalek hernia) but the associated image showed an atypical presentation (a large right-sided hernia with gastric herniation). Because efforts were made to increase the question's difficulty using an atypical form of the disease, the question had a low discriminatory capacity despite its suitable clinical context. The probability curve, virtually a flat line, indicates that the exam takers with the most knowledge had the same probability of getting it right as the exam takers with the least knowledge.

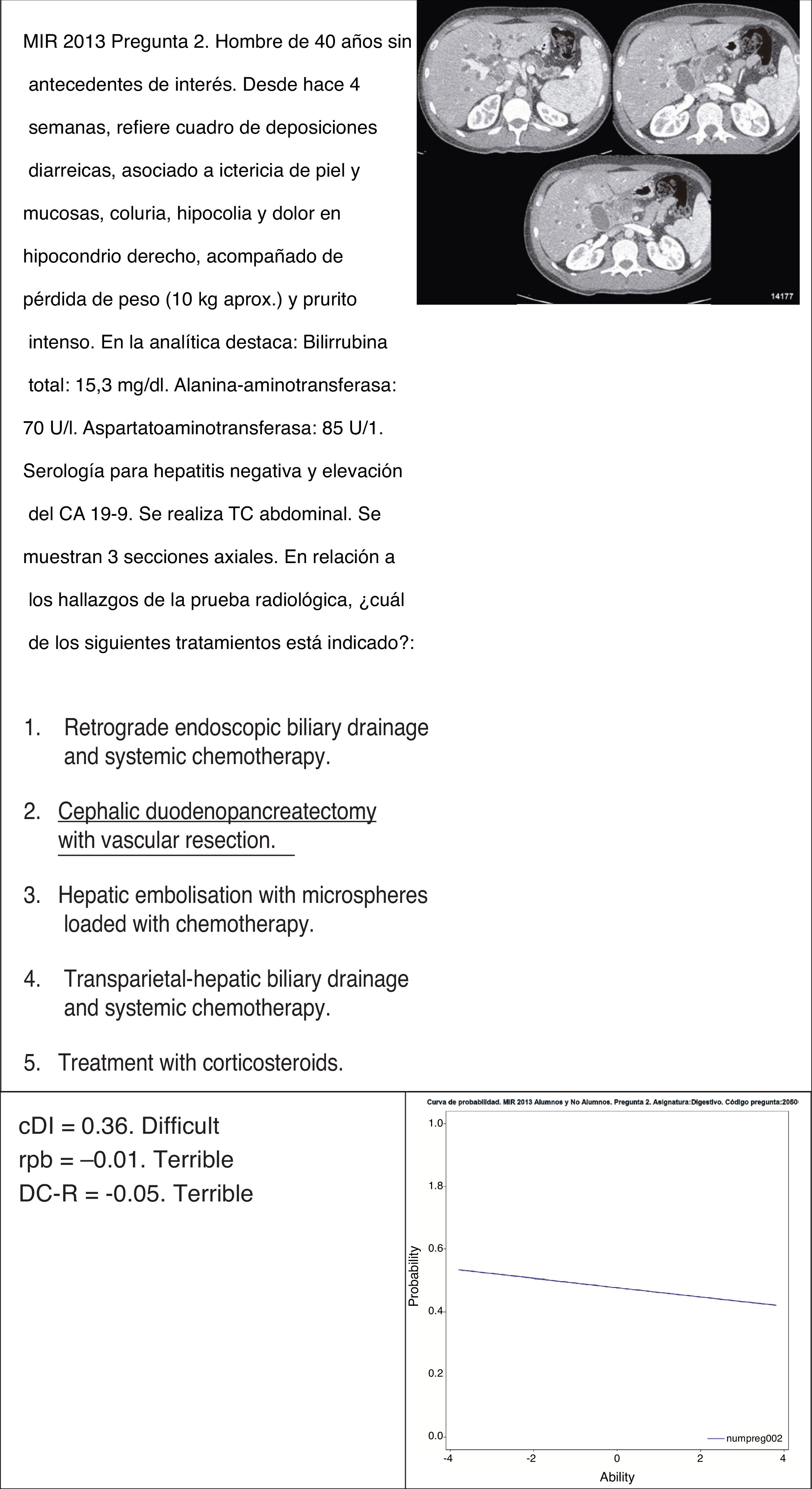

Example of a question with a negative discrimination. The MIR exam takers who scored worse overall had a higher likelihood of answering correctly than those who scored better overall. Efforts were made to render the question about the relevant radiological concept more difficult by asking about criteria for determining that a pancreatic neoplasm is unresectable. Because the question asked about a concept on which opinions are currently divided (the artery is not infiltrated, but the mesenteric venous axis is), the correct response was debatable and the question's discriminatory capacity was decreased.

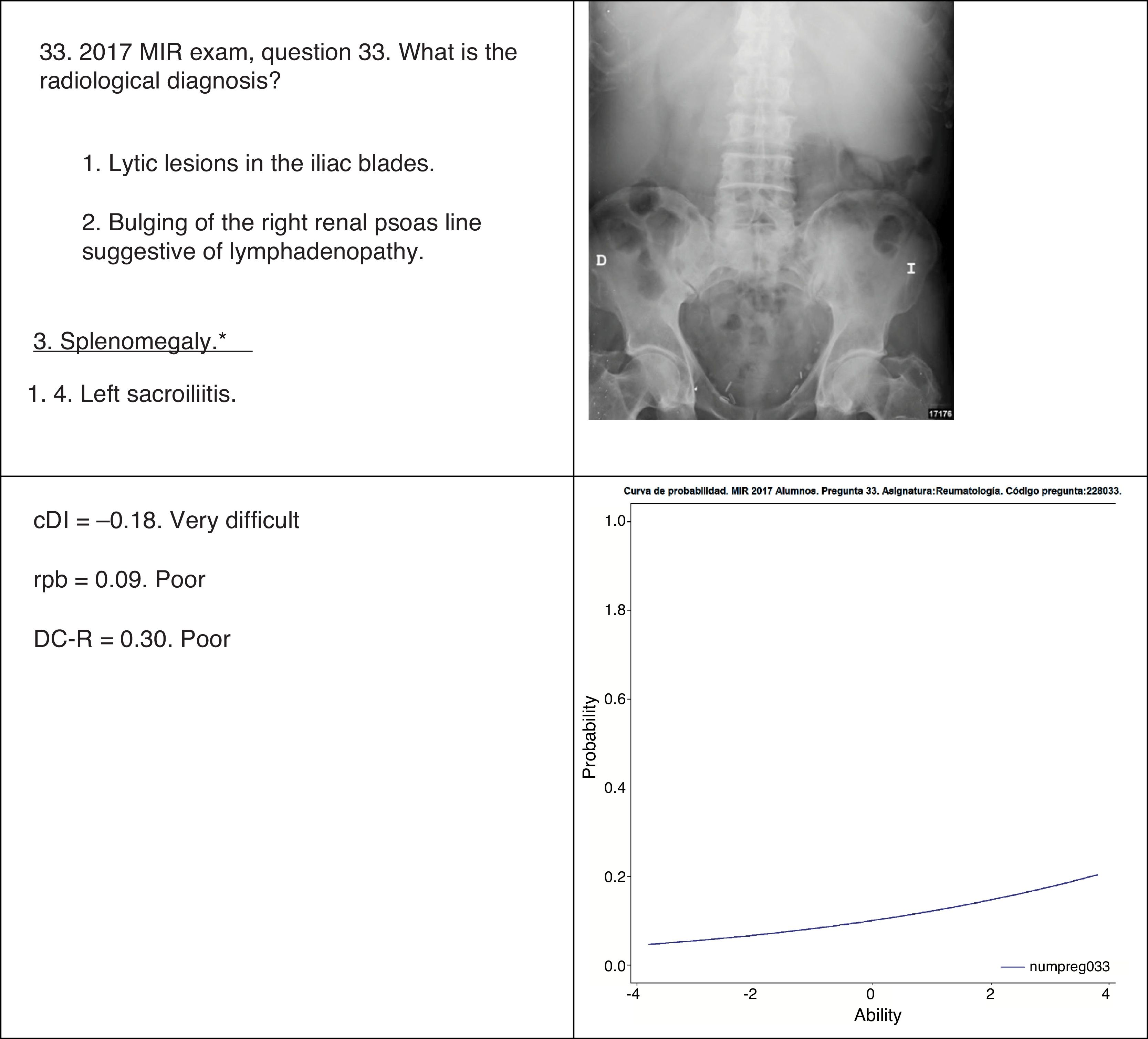

Example of a psychometrically invalid question with a level of difficulty that was so high that its discriminatory capacity was null. This question's main problem is that it uses a radiological image that misleads the exam taker as it features distractors such as a diagnosis of left sacroiliitis and shows an image in which the left sacroiliac joint is not visible. The question was made more difficult by the fact that it asked about a disease (splenomegaly) usually diagnosed by means of another imaging test (ultrasound) and the fact that it did not include any information from the patient's physical examination in its wording.

On the other hand, the questions associated with a higher discriminatory capacity were those that were incorporated into a case report of a simulated patient, those that were consistent with the clinical information supplied and those in which the radiological concept asked about was significant due to its clinical relevance. These questions tended to have an optimal to easy difficulty level (Figs. 9–12). These cases were not analysed in depth, but there are indications that computed tomography images had a higher level of difficulty than simple radiology images.

Example of a radiological question with a good discrimination index. The differential diagnosis that was asked about was colon disease; therefore, the distractors were appropriate with a suitable radiological explanation that justified the response. The clinical context was suitable and the radiological image properly showed the disease without any other images that might have led to errors in interpretation.

Example of a question with an excellent discriminatory capacity, which was maximal, approximately at the median level of knowledge of the sample. This question sought to ascertain whether the exam taker was capable of identifying the different types of cancer in the small intestine and the chemotherapy treatments suited to them. The potential for debating the radiological diagnosis was resolved by including a suitable clinical context and a suitable immunohistochemical presentation.

Example of a question with a good level of discriminatory capacity despite a high level of difficulty. The level of difficulty was high due to the need to assess four images and the fact that it asked about a relatively rare disease, organising pneumonia. The suitable clinical context of the question and the absence of distractors that might have subjected the correct option to significant debate (as the question asked about a differential diagnosis with sarcoidosis, pulmonary fibrosis and amiodarone lung) rendered the question appropriate from a psychometric perspective..

Therefore, from a psychometric point of view, it would be advisable to improve the discriminatory capacity of the questions associated with a radiological image on the MIR exam in order to bring them into closer alignment with the standards for this exam and average values thereof. This means they should fulfil the basic standards for multiple-choice questions mentioned in several studies related to radiology.29

In addition, a significant response-hiding bias was observed (the most common responses were the second and third, and the least common responses were the first and last). On questions with a radiological image from the last MIR exam, the third response was correct in almost 50% of cases. This was probably due to not randomising the response order, primarily for questions on radiological anatomy that referred to numbers included in the image.

The concepts asked about should be basic and represent knowledge of diagnostic imaging that could be possessed by a non-specialist physician, and they should be couched in a suitable clinical context. The distractors used in the question should contain sufficient information to prevent debate of the radiological concept. The image should be of a good quality and should not contain findings that may interfere with the distractors used. The questions associated with an image with the highest discriminatory capacity in the history of the MRI exam were those with a moderate to low difficulty level and suitable wording.

In the exams analysed, when the difficulty of the questions increased, their discriminatory capacity decreased, probably because, from a radiological point of view, an increase in difficulty was associated with rare radiological findings, atypical findings or findings that led to a more extensive or complex differential diagnosis. A difficult clinical diagnosis in a real patient is not the same as a difficult multiple-choice question on a test such as the MIR exam. If the objective that is sought is to increase the difficulty of the question, this may be achieved by asking about less common diseases or diseases with radiological findings that are more difficult to identify on imaging, provided that the fundamental structure of the question is maintained such that it includes a suitable clinical context and uses distractors that cannot be debated as they present findings similar to those in the image.

Providing more clinical information might allow the exam taker to answer radiological questions by inferring the response from the text and not from the image; this, of course, influences the difficulty of the question. The same should occur for questions with a non-radiological image; however, they show a more suitable level of difficulty and discriminatory capacity than radiological questions, even those with little clinical information such as questions relating to pathology or clinical imaging. Therefore, in our opinion, supported by psychometric data, asking about a rare radiological finding or a radiological finding in the absence of a suitable clinical context was the main cause of the low discriminatory capacity of the questions associated with a radiological image. Of course, we do not claim in this study that radiological imaging is unimportant or can be omitted or that therefore direct questions without clinical information cannot be asked. What we do claim based on the results of this study is that, where questions were asked without clinical information and featured misleading clinical information or purely radiological images, their discriminatory capacity decreased (in the setting of our sample of exam takers) and did not attain the standards of the rest of the questions on the MIR exam.

We did not receive any reports from exam takers (through our quality surveys), nor did we ourselves find, that the quality or size of printed radiological images was associated with greater difficulty in answering questions; therefore, we did not consider these things to be variables to take into account when assessing the internal validity of the exam.

ConclusionsPsychometric variables are a set of indicators for evaluating multiple-choice tests that should be studied systematically for any exam administered in an academic context or another context in which knowledge is evaluated. They help to identify questions that are not useful, introduce noise into test marking or suffer from poor technical execution. They also help to identify gaps in learning. In our opinion, psychometric evaluation of responses to MIR exam questions should be used as a criterion to support the efforts of the exam's marking board to nullify certain questions.14

Questions with radiological imaging were found to have lower-than-average values for the MIR exam in terms of discriminatory capacity and to be more difficult for exam takers to answer correctly. Questions from the MIR exam associated with a non-radiological image, when compared, also revealed a lower discriminatory capacity, albeit less pronounced.

In order to attain the standards of the MIR exam, it is necessary to maintain a suitable structure in the preparation of the questions on the exam in terms of clinical context, appropriate use of distractors and a lower level of difficulty, which may be achieved through the use of images with typical radiological findings.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for study integrity: EMQ.

- 2

Study conception: EMQ, FSL.

- 3

Study design: EMQ, FSL, SMCG, JBR, JCB.

- 4

Data collection: EMQ, FSL, MCR, JBR, JCB.

- 5

Data interpretation and analysis: EMQ, FSL, MCR, JBR, JCB.

- 6

Statistical processing: EMQ, EFL, MCR.

- 7

Literature search: EMQ.

- 8

Article drafting: EMQ.

- 9

Critical review of manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: EMQ, SMCG, JBR.

- 10

Approval of final version: EMQ, SMCG, MCR, JBR.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Murias Quintana E, Sánchez Lasheras F, Costilla García SM, Cadenas Rodríguez M, Calvo Blanco J, Romero, Baladrón Romero J. Análisis psicométrico de las preguntas asociadas a imágenes radiológicas en el examen para médico interno residente en España. Radiología. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rx.2019.04.005