In pediatric patients with sarcomas, hepatoblastomas, or other types of primary tumors, lung metastases are often found at diagnosis or during follow-up. The wide variety of primary tumors and clinical situations makes management and follow-up of these patients challenging. Chest CT is the best way to detect the dissemination of disease to the lungs. Many pulmonary nodules are nonspecific, and many might not be pathological. Others have characteristics that make them suspicious. Although there are some general features that indicate that a pulmonary nodule is likely to be a metastasis, sometimes the meaning of these features depends on the primary tumor. Furthermore, metastases can develop during the course of the disease, and the protocols for follow-up are different for different primary tumors.

We review the different protocols used at our hospital for the primary tumors that most often metastasize to the lungs, including the criteria for lung metastases and the follow-up for each primary tumor.

En pacientes pediátricos con sarcomas, hepatoblastomas u otros tipos de tumores primarios es frecuente encontrar metástasis pulmonares en el inicio o durante el seguimiento. El manejo y seguimiento es un reto dada la gran diversidad de tumores primarios y situaciones clínicas. La tomografía computarizada de tórax es la mejor forma de detectar la diseminación pulmonar. Muchos nódulos pulmonares son inespecíficos y pueden no tener significado patológico. Otros pueden tener características que los hagan sospechosos. Hay algunos criterios generales para considerar a un nódulo pulmonar probablemente metástasis, pero a veces depende del tumor primario. Además, las metástasis se pueden desarrollar a lo largo del curso de la enfermedad, siendo los protocolos de seguimiento distintos según el tumor primario. Revisamos los diferentes protocolos utilizados en nuestro hospital para los tumores primarios que más frecuentemente metastatizan en el pulmón, incluidos los criterios de metástasis pulmonar y el seguimiento para cada tumor primario.

The lungs are the organ most commonly involved in the majority of solid paediatric tumours. Osteosarcoma, Wilms’ tumour (nephroblastoma), tumours from the Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumours, rhabdomyosarcoma, and hepatoblastoma are the most common primary tumours that present with pulmonary metastases or develop throughout the course of the disease.1,2

We have two radiological tools available for the monitoring and detection of pulmonary nodules in paediatric oncology patients: chest x-ray and chest computerised tomography (CT). The chest x-ray is taken in the anteroposterior projection (AP, a single projection) in patients under 4–5 years of age, depending on the level of collaboration, and in the posteroanterior (PA) projection for radiation protection of the mammary gland in collaborating patients. With regard to the chest CT, there are numerous parameters than can modify the image and diagnostic test and whose description is beyond the scope of this study, but which can be summarised as: image acquisition parameters to adapt the scan according to the patient's age, weight and degree of collaboration (sedation, general anaesthesia, tube current, slice thickness, pitch, etc.) and post-processing parameters (detection in maximum intensity projection (MIP) and measurement in multiplanar reconstruction, among others), which can affect the accuracy and reproducibility of the radiological report. With respect to the technique, the chest CT for the detection of pulmonary nodules is usually performed without contrast except in rhabdomyosarcoma of the limbs and abdomen, in which case it is performed with contrast.3

The chest CT has been proven to have a higher sensitivity than the chest x-ray for the detection of pulmonary nodules. In CT scans, pulmonary metastases can usually be seen as well-defined, round nodules. But not all pulmonary modules are metastases. There is a wide range of benign processes that can manifest as a pulmonary nodule, for example, granulomas, infection, inflammation, intrapulmonary lymph nodes, vascular malformations, hamartomas and atelectasis.4 There are currently a lot of challenges associated with considering a pulmonary nodule as metastatic in a child with cancer:

- •

The high prevalence of pulmonary nodules in children without cancer.

- •

The difficulties in determining whether a single nodule is benign or malignant based on radiological images. Efforts have been made in the radiological literature to clarify which nodules should be considered benign: for example, calcified nodules in patients without osteosarcoma should be considered calcified granulomas, and triangular perifissural nodules should, in all cases, be considered benign pulmonary lymph nodes.5 But, apart from that, there are no reliable CT features that enable us to differentiate between a benign pulmonary nodule and pulmonary metastasis.5,6

- •

Differences in lung CT acquisition between different equipment include not just acquisition parameters (such as slice thickness and the pitch or the tube current), but also degrees of inspiration, sedation/general anaesthesia for young patients or acquisition during gentle respiration.

- •

Significant interobserver variability in the detection of small pulmonary nodules and in the individual interpretation of nodules.

Although the lung CT can be “sensitive” for the detection of pulmonary nodules, its specificity is low for the diagnosis of pulmonary metastasis, with proven biopsy false positive rates of 32-65% in children with cancer with suspected pulmonary metastases.5,6 Furthermore, the Fleischner guidelines, developed for the adult population, do not apply to children.6,7

The protocols of the follow-up guidelines can be a challenge for both oncologists and paediatric radiologists because of, on the one hand, the different criteria for pulmonary metastasis depending on the primary tumour and, on the other, the different indications for obtaining histological samples from these pulmonary nodules depending on the primary tumour, the oncological staging and the patient's clinical situation.

ReviewWe reviewed the most important clinical trial guidelines for the diagnosis and follow-up of the most common paediatric solid tumours that metastasise to the lung: osteosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumours, hepatoblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and Wilms’ tumour.

We divided our attention between two different aspects:

- •

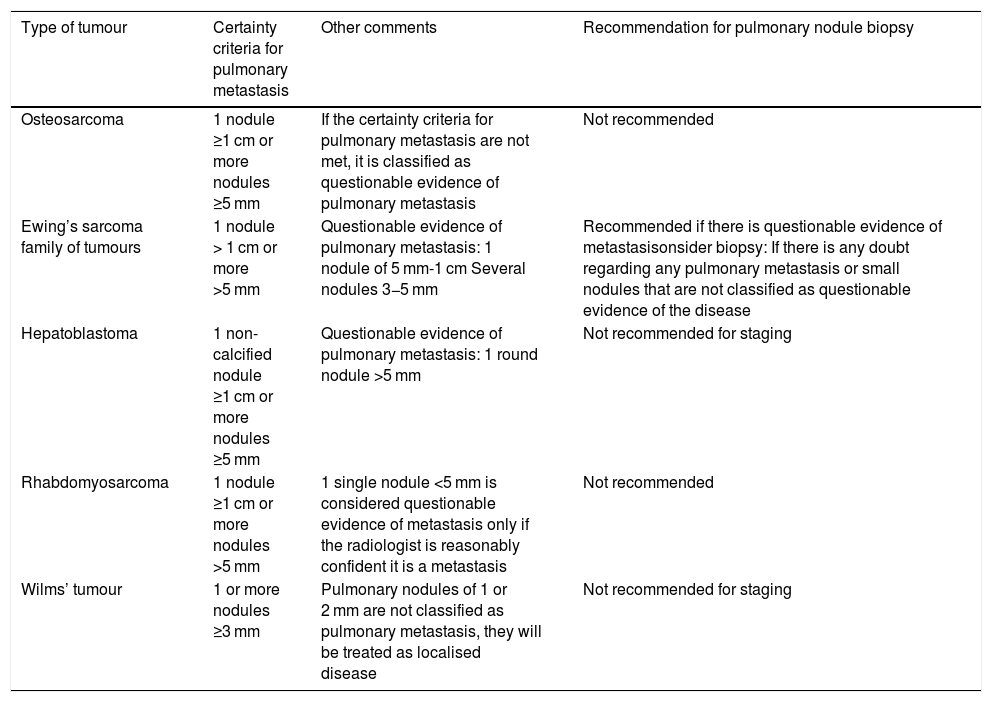

Criteria used to consider a pulmonary nodule as a metastasis according to the tumour (Table 1).

Table 1.Summary of pulmonary metastasis criteria by primary tumour.

Type of tumour Certainty criteria for pulmonary metastasis Other comments Recommendation for pulmonary nodule biopsy Osteosarcoma 1 nodule ≥1 cm or more nodules ≥5 mm If the certainty criteria for pulmonary metastasis are not met, it is classified as questionable evidence of pulmonary metastasis Not recommended Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumours 1 nodule > 1 cm or more >5 mm Questionable evidence of pulmonary metastasis: 1 nodule of 5 mm-1 cm Several nodules 3−5 mm Recommended if there is questionable evidence of metastasisonsider biopsy: If there is any doubt regarding any pulmonary metastasis or small nodules that are not classified as questionable evidence of the disease Hepatoblastoma 1 non-calcified nodule ≥1 cm or more nodules ≥5 mm Questionable evidence of pulmonary metastasis: 1 round nodule >5 mm Not recommended for staging Rhabdomyosarcoma 1 nodule ≥1 cm or more nodules >5 mm 1 single nodule <5 mm is considered questionable evidence of metastasis only if the radiologist is reasonably confident it is a metastasis Not recommended Wilms’ tumour 1 or more nodules ≥3 mm Pulmonary nodules of 1 or 2 mm are not classified as pulmonary metastasis, they will be treated as localised disease Not recommended for staging - •

The radiological management that should be provided for the initial diagnosis and follow-up during and after treatment.

As our centre is not officially included in clinical trials on osteosarcoma8 and the Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumours9, in these two neoplasms we use the SEHOP (Sociedad Española de Hematología y Oncología Pediátrica [Spanish Society of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology]) and SIOP (Sociedad Internacional de Oncología Pediátrica [International Society of Paediatric Oncology]) recommendations. For all other tumours, we reviewed the following protocols and clinical trials:

- •

Hepatoblastoma: PHITT. Version 1.0 b. 201710.

- •

Wilms’ tumour: SIOP-RTSG 2016. Version 1.211.

- •

Rhabdomyosarcoma: RMS 2005. Version 2.03.

These protocols were reviewed with the paediatric oncology department to adapt them to a tertiary hospital's clinical practice.

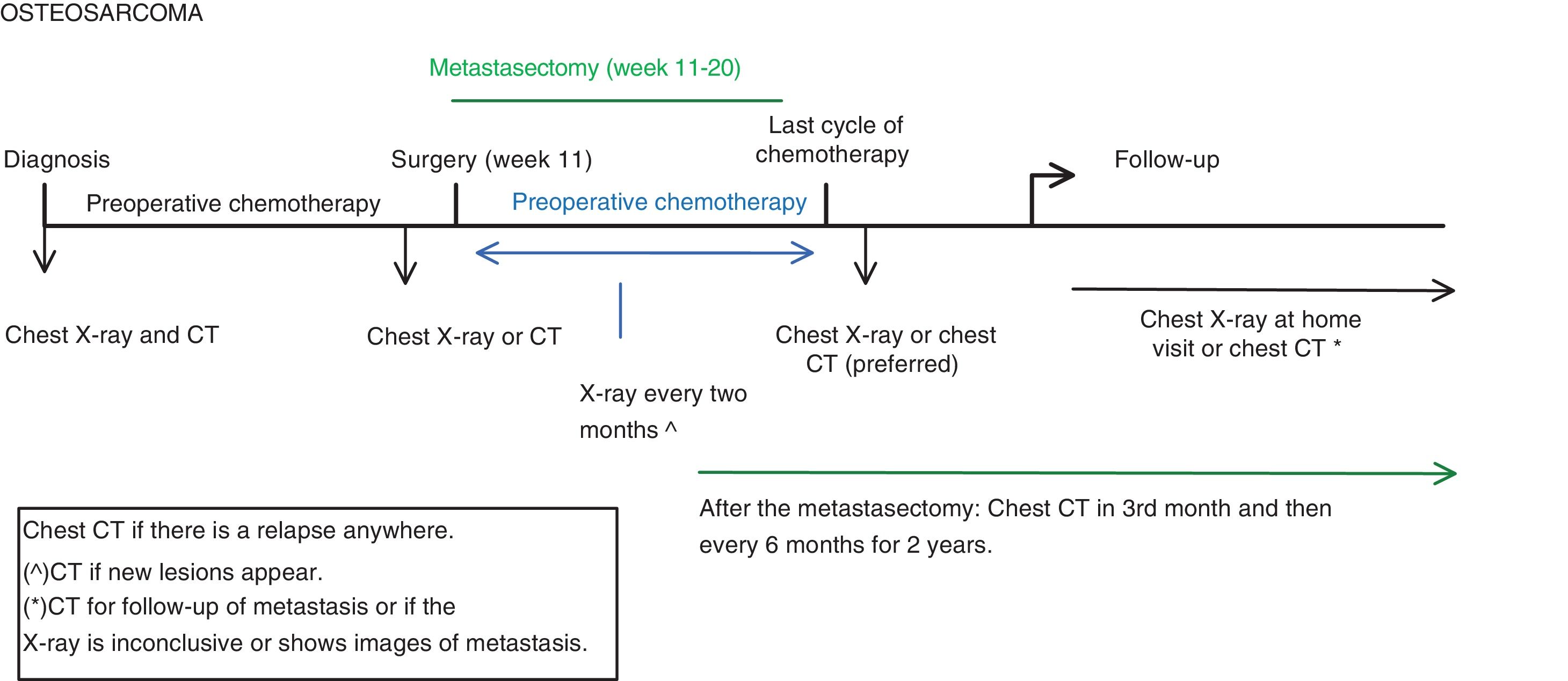

OsteosarcomaBelow, we show an adaptation of the EURAMOS-1 protocol, version 3.0 of 20118, together with clinical practice and SEHOP/SIOP guidelines.

The thoracic diagnostic tests performed are the chest CT and plain chest X-ray during the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up phases (Fig. 1)8:

- •

At diagnosis: chest X-ray and chest CT. The chest X-ray is taken so that it can be compared with future X-rays taken during follow-up.

- •

Before surgery: chest X-ray or CT. At our centre, a chest X-ray is performed unless there is known pulmonary metastasis or CT findings at diagnosis that require CT control.

- •

During post-surgical chemotherapy: chest X-ray every 2 months.

- •

After the last cycle of chemotherapy: a chest CT is preferred.

- •

During follow-up: X-ray or CT:

- -

The chest X-Ray is performed at each clinic visit, which is usually:

- •

1st and 2nd year: every 6 weeks-3 months.

- •

3rd and 4τη year: every 2–4 months.

- •

5rd-10th year: every 6 months.

- •

>10 years: every 6–12 months.

- -

The performance of the CT depends on the clinical situation; it is necessary if the X-ray is not conclusive or a new lesion appears. It is also performed in patients who have a lesion that we want to follow-up on with CT, generally alternating X-ray and CT at each check-up.

The certainty criteria for pulmonary metastasis in CT are (Table 1):

- •

1 nodule >1 cm.

- •

3 or more nodules >5 mm.

If these criteria are not met (1 nodule smaller than 1 cm or several nodules smaller than 5 mm), the nodules are characterised as possible metastatic disease.

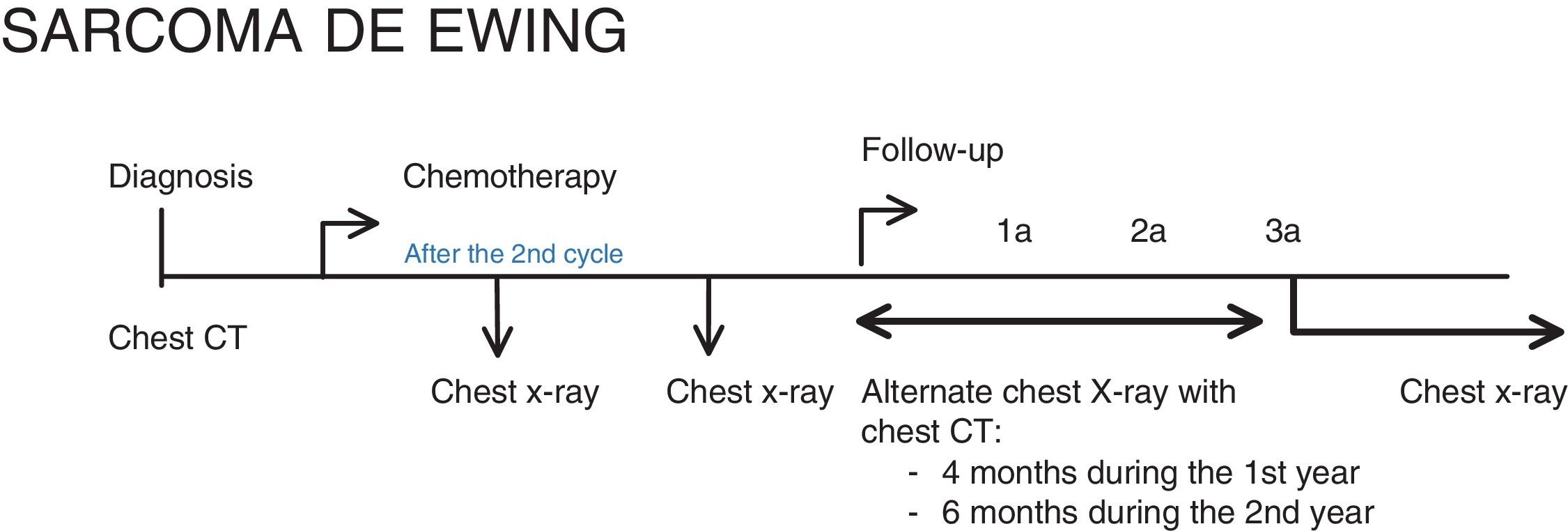

Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumoursBelow, we show an adaptation of the EURO EWING 2012 protocol9 according to clinical practice and SEHOP/SIOP guidelines. At our centre, only the standard treatment (branch A) is used. Therefore, we are also showing the follow-up after this therapeutic management, modified for a closer follow-up.

The chest imaging tests to be performed are (Fig. 2):

- •

At diagnosis: Chest CT.

- •

After the second cycle of chemotherapy: Chest CT.

- •

At the end of treatment: Chest CT.

- •

For the follow-up: at our centre we perform chest X-rays alternating with chest CT scans every 4 months during the first year, every 6 months in the second year and only X-rays from the third year of follow-up.

The criteria for considering a pulmonary nodule a metastasis are divided into (Table 1):

- •

Evidence of pulmonary metastases: one nodule bigger than 1 cm or more than one nodule larger than 5 mm.

- •

Questionable evidence of pulmonary metastasis: one nodule of 5−9 mm or more than one nodule of 3−5 mm. Biopsy is recommended in these cases.

- •

No clear evidence of pulmonary metastases: one nodule smaller than 5 mm or more than one nodule smaller than 3 mm. These nodules should be assessed on an individual basis.

In patients with a primary tumour located in the chest wall, pleural effusion with or without pleural nodules is considered a locoregional disease.9

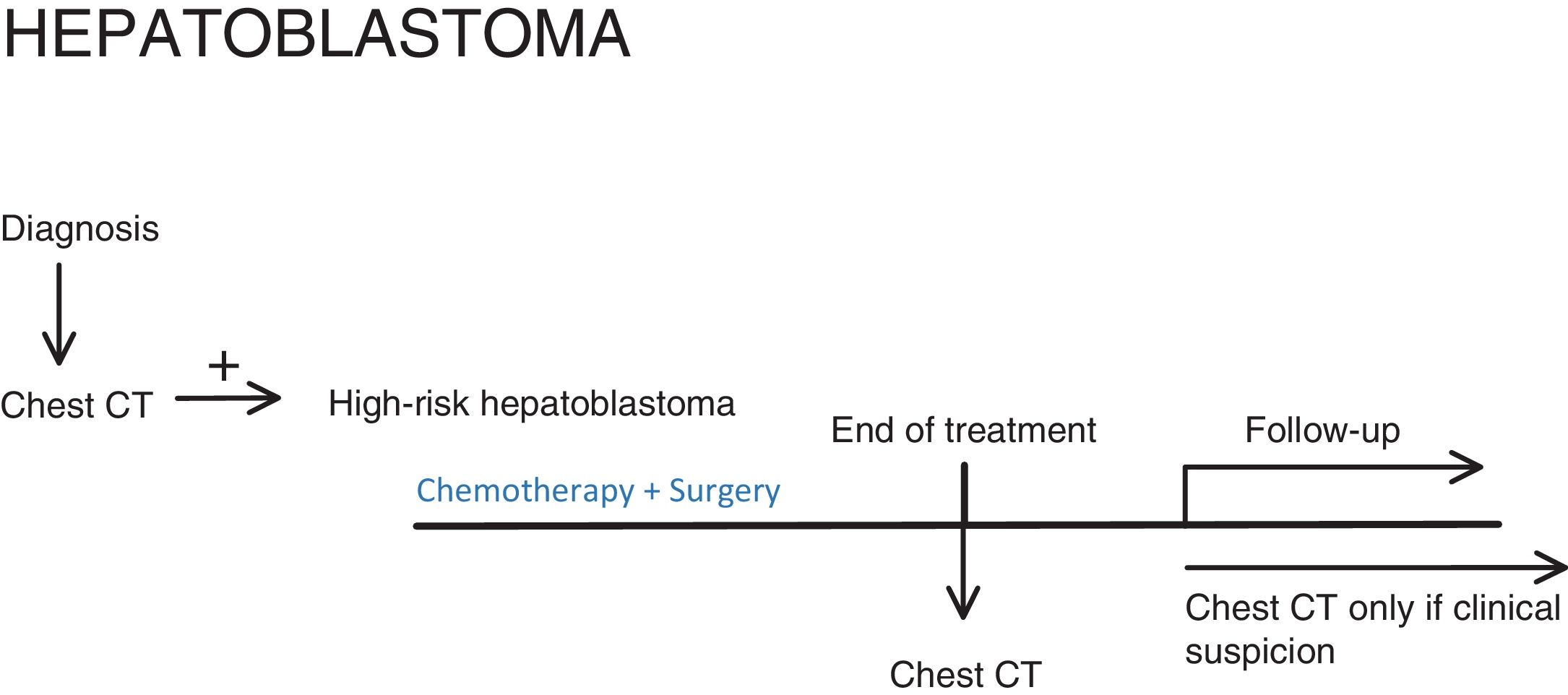

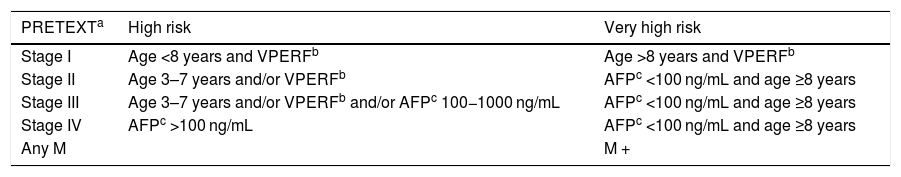

HepatoblastomaBelow, we show the 2017 PHITT protocol, version 1.0b10.

The chest imaging tests that should be performed are (Fig. 3):

- •

At diagnosis: Chest CT, to stratify the patient's risk.

- •

At the end of treatment: Chest CT in patients with high metastatic risk (Table 2).

Table 2.Criteria for high risk and very high risk of metastasis in patients with hepatoblastoma.

PRETEXTa High risk Very high risk Stage I Age <8 years and VPERFb Age >8 years and VPERFb Stage II Age 3–7 years and/or VPERFb AFPc <100 ng/mL and age ≥8 years Stage III Age 3–7 years and/or VPERFb and/or AFPc 100−1000 ng/mL AFPc <100 ng/mL and age ≥8 years Stage IV AFPc >100 ng/mL AFPc <100 ng/mL and age ≥8 years Any M M + - •

During follow-up: Chest CT only for M + (patients who already had metastasis at diagnosis or developed them during the course of the disease).

The defining characteristics of pulmonary metastasis have not been studied specifically but to be classified as pulmonary metastasis, it should be (Table 1):

- •

A non-calcified nodule ≥1 cm.

- •

Two or more nodules ≥5 mm.

- •

Any nodule confirmed by biopsy or metastasectomy.

Biopsy is not necessary for staging, given the low probability of other lesions imitating the metastasis in this clinical context.10

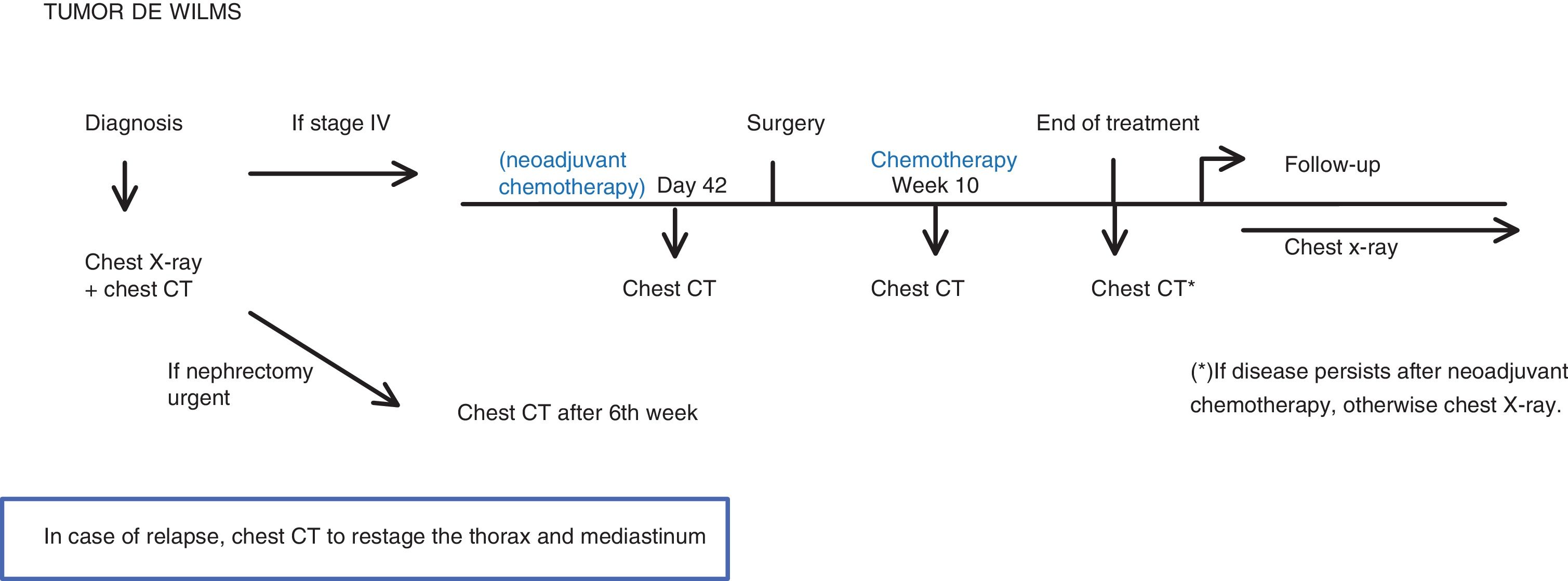

Wilms’ tumourBelow, we show the 2016 SIOP-RTSG protocol, version 1.211. At our centre, we use the European treatment protocol (neoadjuvant chemotherapy and subsequent surgery).

The chest CT should be performed (Fig. 4):

- •

At diagnosis.

- •

If metastasis is found (stage IV), perform CT:

- -

Prior to surgery

- -

In the 10th week of chemotherapy treatment.

- -

At the end of the chemotherapy treatment: only if there is residual disease. Otherwise a simple chest X-ray is sufficient.

- •

When there is suspicion of recurrence.

- •

If an emergency nephrectomy had to be performed with no evidence of metastasis: Chest CT 6 weeks after surgery.11

The imaging test during follow-up is the chest X-ray, following the European protocol.

The criterion for pulmonary metastasis is a non-calcified nodule, with well-defined borders, larger than 3 mm. Any pulmonary nodule, irrespective of size, should be reported11 (Table 1).

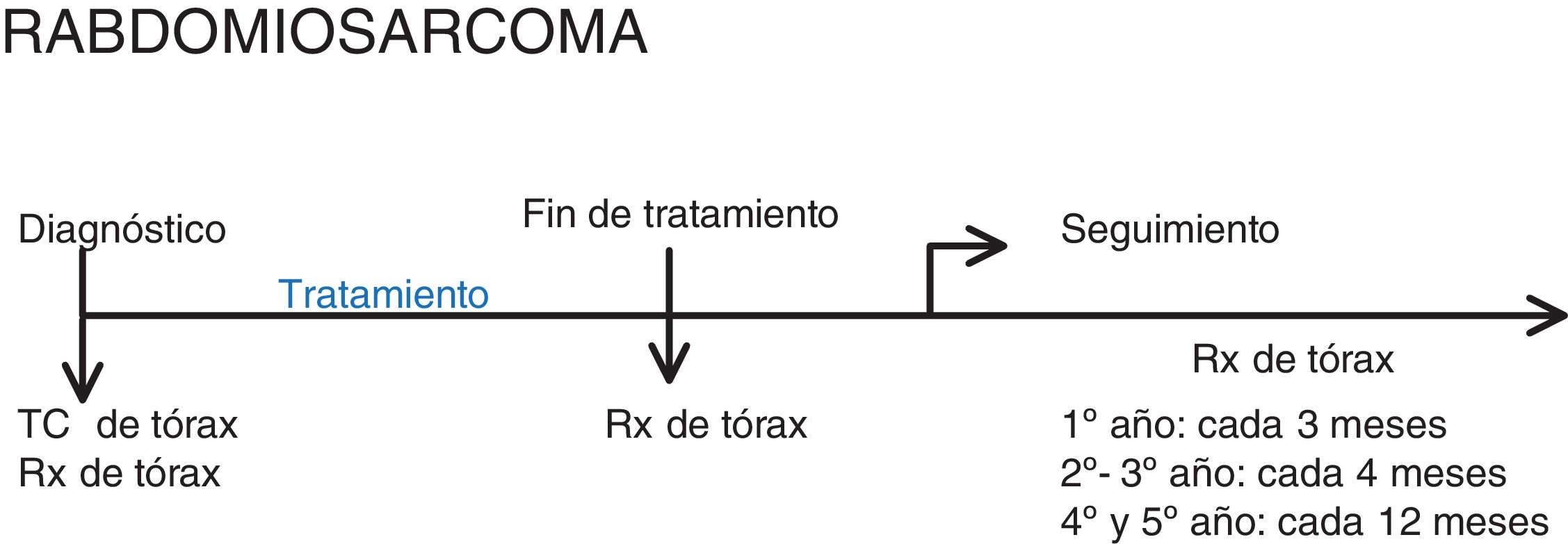

RhabdomyosarcomaBelow, we show the 2005 RMS protocol, version 2.0.3

Chest imaging should be performed (Fig. 5):

- •

At diagnosis: chest X-ray and chest CT. As in osteosarcoma, both are performed since follow-up is with chest X-ray, in order to be able to compare.

- •

After treatment: chest X-ray.

- •

Follow-up: chest X-ray.

When the tumour originates from the abdomen or limbs, the study must be performed with intravenous contrast, while if the tumour originates from other locations, this is only recommended.

Although there are no 100% specific criteria for pulmonary metastasis, the following are considered (Table 1)3:

- •

Clear evidence of metastasis: one nodule of 1 cm or more or several nodules larger than 5 mm.

- •

Questionable evidence of metastasis: nodules smaller than 5 mm only if the radiologist is reasonably confident that they are metastases. Biopsy is not recommended in these cases, as they would be considered micrometastases, which are probably already present in all the local rhabdomyosarcomas.

Pulmonary metastases in a paediatric oncological patient are a not uncommon form of tumour dissemination. The criteria and follow-up protocols for metastasis depend on the type of tumour. To clarify the steps to follow in the course of the most common paediatric tumours that metastasise to the lungs, we have developed some algorithms based on the different clinical situations and protocols used at our hospital.

AuthorshipPerson responsible for the integrity of the study:

Study conception: CGH.

Study design: CGH.

Data collection: MCCC, JAS.

Data analysis and interpretation: MCCC, JAS.

Statistical processing:

Literature search:

Drafting of the article: MRP.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: CGH, MRP, VPA.

Approval of the final version: CGH.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical responsibilitiesNone.

Please cite this article as: Cruz-Conde MC, Gallego Herrero C, Rasero Ponferrada M, Alonso Sánchez J, Pérez Alonso V. Manejo práctico de los nódulos pulmonares en las neoplasias pediátricas más frecuentes. Radiología. 2021;63:245–251.