To evaluate the long-term outcomes of renal tumor ablation, analyzing efficacy, long-term survival, and factors associated with complications and therapeutic success.

Material and methodsWe retrospectively reviewed 305 ablations (generally done with expandable electrodes) of 273 renal tumors between May 2005 and April 2019. We analyzed survival, primary and secondary efficacy, and complications according to various patient factors and tumor characteristics.

ResultsMean blood creatinine was 1.14 mg/dL before treatment and 1.30 mg/dL after treatment (p < 0.0001). Complications were observed in 13.25% of the ablations, including major complications in in 4.97%. Complications were associated with age (p = 0.013) and tumor diameter (p < 0.0001). Primary efficacy was 96.28%. Incomplete ablation was more common in lesions measuring > 4 cm in diameter (p = 0.002). Secondary efficacy was 95.28%. The only factor associated with the risk of recurrence was the size of the tumor (p = 0.02). Overall survival was 95.26% at 1 year, 77.01% at 5 years, and 51.78% at 10 years, with no differences between patients with malignant and benign lesions. Mortality was higher in patients with creatinine >1 (p = 0.05) or ASA > 2 (p = 0.0001).

ConclusionsPercutaneous ablation is extremely efficacious for renal tumors; it improves the prognosis of renal carcinoma to the point where it does not differ from that of benign lesions. Complications are rare. Like survival, complications are associated with age and overall health status.

Valorar resultados a largo plazo de la ablación de tumores renales analizando eficacia, supervivencia a largo plazo y factores asociados con complicaciones y éxito terapéutico.

Material y métodosRevisión retrospectiva de 305 ablaciones, en general usando radiofrecuencia con electrodos desplegables, sobre 273 lesiones de tumores renales entre mayo de 2005 y abril de 2019. Se analizó supervivencia, eficacia primaria y secundaria y complicaciones relacionándolas con diversos factores del paciente y características de los tumores tratados.

ResultadosLa creatinina en sangre media previa al tratamiento fue de 1,14 mg/dL y al año de 1,30 mg/dL (p < 0,0001). Hubo complicaciones en el 13,25% de las ablaciones (mayores, 4,97%) que se relacionaron con edad (p = 0,013) y diámetro tumoral (p < 0,0001). La eficacia primaria fue del 96,28%. Las lesiones de más de 4 cm fueron más propensas a presentar ablaciones incompletas (p = 0,002). La eficacia secundaria: fue del 95,28%. El riesgo de recurrencia se relacionó solo con el tamaño del tumor (p = 0,02). La supervivencia global fue del 95,26% al año, 77,01% a los 5 años y 51,78% a los 10 años. No se observaron diferencias en función de la naturaleza maligna o benigna de la lesión tratada. La mortalidad aumentaba en pacientes con creatinina superior a 1 (p = 0,05) o ASA > 2 (p = 0,0001).

ConclusionesLa ablación percutánea de tumores renales es una técnica de altísima eficacia, que permite igualar el pronóstico de un carcinoma renal, tras el tratamiento, al de una lesión benigna. Las complicaciones son muy infrecuentes y se relacionan, al igual que la supervivencia, con edad y estado de salud del paciente.

The therapeutic management of renal tumours has increasingly included percutaneous ablation since it was first applied in 1997.1,2 While radiology guidelines were quick to adopt this method as an alternative to nephrectomy,3 it has only recently been included in the urological clinical guidelines, and even then only in response to certain indications.4

Percutaneous ablation has repeatedly demonstrated its effectiveness in treating renal carcinomas.3,5–12 However, its place in the treatment algorithm and the indications for ablation instead of the two main alternatives—partial nephrectomy and active surveillance—have yet to be defined.6,9–11,13–23 Persisting concerns surrounding the risk of post-treatment recurrence and its impact on long-term survival have slowed its adoption.24

There are also technical matters to consider, such as factors associated with the risk of complications or recurrence, which have given rise to several scoring systems.25–29 The merits of the various guidance or ablation techniques, as well as the various energy sources currently available are also under discussion.6,7,12,30

To contribute to the evidence base for this technique we present the long-term outcomes of a series of renal tumours treated with ablation, mainly using radiofrequency with expandable electrodes, with a focus on its effectiveness, long-term survival and the factors associated with complications and therapeutic success.

Material and methodsPatientsA retrospective review was conducted of the clinical data for all patients who underwent renal tumour ablation procedures in the Hospital Universitario Basurto between May 2005 and April 2019. There is at least two years of post-treatment clinical data relating to the procedure and follow-up for all patients and all data relating to the procedure and post-procedure follow-up were recorded. This case series includes cases published in a previous study.31

Candidates for renal ablation treatment were selected by the urology department from patients attending consultations after the detection of a renal tumour indicative of renal cell carcinoma. The first-line treatment at the centre for renal cortical tumour is (radical or partial) nephrectomy. No biopsy is performed prior to treatment unless the tumour is suspected to be extrarenal in origin or benign. The urology department indicated ablation treatment instead of nephrectomy in cases of a solitary kidney, bilateral renal neoplasms, Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, surgical risk due to comorbidity, advanced age, patient choice or refusal to undergo surgery. The relevance of the indication and the technical feasibility of the method were then discussed by the urology department and the diagnostic radiology department’s interventional ultrasound team.

Requirements for treatmentThe following requirements had to be met to perform the treatment:

▪Tumour visible on ultrasound or computed tomography (CT)

▪No evidence of metastatic spread

▪No evidence of tumour extension into the renal vein at the time of treatment

Non-essential requirement:

▪Diameter no greater than 5 cm (the maximum ablation diameter is taken from the radiofrequency ablation system)

Prior to the procedure, all patients underwent CT or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, both with and without intravenous contrast, to visualise the lesion. Before treatment, all patients underwent a planning ultrasound, in which the tumour diameter was measured, as this informed the choice of material. Also, all patients underwent routine laboratory tests, which included coagulation tests, complete blood count and renal function tests, and were assessed by the anaesthesia team. All patients were asked to sign an informed consent to undertake the procedure.

As no surgical sample would be obtained after the procedure, a biopsy of the lesion was taken from all patients to document the nature of the tumour. This was performed immediately prior to the ablation, except in cases where a biopsy had already been taken. In all cases, the biopsy was obtained using a freehand ultrasound-guided technique, with an 18 G automatic needle (BioPince; Argon). The specimens obtained were processed histologically, including the use of immunohistochemical techniques.32

AblationIn all but five cases radiofrequency ablation was performed. The system used consisted of a 200 W radiofrequency generator (RF 3000; Boston Scientific) connected to a LeVeen multitine electrode. When retracted, this electrode is shaped like a needle. When deployed, the tines advance into an umbrella shape array upon insertion into the tumour to be treated. The distal electrode array has multiple diameter settings that determine ablation volume. Three to five cm diameter electrodes were used. The system also includes dispersive electrodes (grounding pads) that are placed on the patient’s thighs to close the electrical circuit.

Microwave ablation was performed in five cases. This technique was chosen for tumours which measured more than 4 cm in their shortest diameter (T1b), as, from prior experience, radiofrequency ablation has failed for tumours with diameters over this size. Two antennas were used: Emprint (Medtronic) and 3 HS (Amica). Both systems use cooled shaft antennas and ablation volume depends on the time and power selected.

The oncological criterion of ensuring an ablation diameter 1–2 cm greater than the maximum tumour diameter was used to choose the electrode or technique applied to each case.

In all but two cases, the procedures were performed using ultrasound-guided imaging with HD3500, HD5000, IU11 and IU22 systems (Philips Medical Systems). In two cases the lesion was not visible on ultrasound, and CT-guided imaging was used (Somatom 4 Plus Volume Zoom or Somatom Sensation Open, Siemens Healthcare).

All patients were administered with local anaesthetic at the electrode insertion site (10 mL of 1% lidocaine). In all cases, the electrode—or antenna—was inserted using guided imaging until it reached the centre of the tumour. At this point, in radiofrequency procedures, the array was deployed.

The position of the needle or array was then checked to ensure it was suitably positioned to treat the lesion with a surrounding safety margin. In all cases care was taken to access the tumour safely and on the first try, avoiding repeated entries into the tumour with the electrode. In the case of the LeVeen, once the array is deployed, the electrode is firmly anchored to the lesion. This allows for some movement of the patient should a change of position be necessary.

In tumours whose proximity to a digestive structure could lead to adjacent structure heat damage as a result of the application of radiofrequency to a nearby lesion, a 5% isotonic glucose solution was injected into the perirenal space between the tumour and the digestive structure, until the two were separated by at least 2 cm. The volume of glucose solution injected varied between 50–200 cc, depending on the characteristics of each patient. In tumours located near the ureter (medial region and lower pole of the kidney), a ureteral catheter positioned up to the renal pelvis was used to irrigate the area with cold saline solution during the procedure.

Energy was applied to the electrode or the antenna from the generator following manufacturer-issued protocols. This produced a localised temperature increase around the electrode which was responsible for the heat injury to the treatment area.

The procedure was monitored periodically with ultrasound, which showed the progressive appearance of bubbles around the tines, the result of tissue water vaporisation. These bubbles progressively occupied the whole ablation area by the end of the procedure.

Radiofrequency ablation was considered complete when there was a sudden significant increase in impedance of the treated tissue (known as roll-off). This indicated necrosis and desiccation and was accompanied by a consequent increase in electrical impedance. Roll-off was always achieved twice. When roll-off was not reached after 20 min of ablation, the tines were retracted to reduce the array diameter by 1.5 cm, and the procedure continued. When roll-off was achieved at this smaller diameter, the electrode was advanced again, and the procedure restarted. It was often necessary to retract the electrodes in this way for tumours over 4 cm in diameter. For tumours with a maximum diameter of between 4 and 5 cm in diameter, 2–3 overlapping ablation procedures were performed, in an attempt to treat the entirety of the tumour.

In the case of microwave ablation, the procedure was terminated upon completion of the manufacturer’s recommended protocol.

All procedures were performed with the patient under conscious sedation using a combination of intravenous (IV) propofol and fentanyl. During the procedure, patients were under the direct supervision of an anaesthetist who continually monitored their vital signs, including heart rate, oxygen saturation and blood pressure. All procedures were carried out by three radiologists with years of experience in interventional techniques.

Post-procedural care and follow-upAfter the procedure, the patient remained in hospital for 24 h. Immediately after the procedure, the patient was sent to a day unit with analgesics prescribed by the anaesthetist. Once there, the patient’s vital signs and punction site were checked every hour for five hours following the procedure. The next day, the patient was checked again with an ultrasound at the interventional ultrasound unit to check for possible acute complications, after which, if no complications were found, they were discharged. A contrast-enhanced ultrasound was also performed to provide an initial assessment of the potential outcome of the ablation.

One month after the ablation, all patients underwent a follow-up CT (Somatom 4 Plus Volume Zoom, Siemens) to check for any possible early complications or incomplete ablation of the tumour. Follow-up after that consisted of a three-monthly reassessment of all patients for two years, during which time examinations alternated between MR imaging (Magnetom Symphony, Siemens) and CT, both using IV contrast. At the end of two years, the patient was transferred to the urology department for monitoring, following the same monitoring protocol as for patients who have undergone a partial nephrectomy.

The CT series performed included non-contrast, corticomedullary phase and excretory phase, with reconstructions in axial, sagittal and coronal planes in the treated region. Ablation was considered adequate when there was an absence of contrast enhancement in the treated lesion, defined as an increase of less than 10 HU in comparison with the non-contrast series. In the case of MRI, T1 and T2 sequences, fat suppression, and a dynamic study following the administration of gadolinium were obtained. Ablation was considered adequate when there was an absence of contrast enhancement in the treated lesions, defined as less than a 15% increase in signal intensity in comparison with the non-enhanced sequence. The presence of any residual tumour in the first follow-up session (at one month) was considered incomplete ablation. Tumour detection in later checks was considered recurrence. Patients with incomplete ablation or tumour recurrence were considered candidates for further ablation treatment.

Data analysisDemographic data, characteristics of treated tumours and their pathological diagnosis, the electrode used and the location of the tumour in the kidney were collected for all patients. Radiological findings observed during post-procedural follow-up were also recorded, as were the technical peculiarities of each procedure and complications observed. Tumours were considered exophytic where more than half the tumour protruded from the outer surface of the kidney.

Treatment success was determined according to Society of Interventional Radiology (JVIR) standards33:

- □

Technical success: when the tumour was completely treated (including where a staged approach was taken). It is determined in the first follow-up imaging study.

- □

Primary efficacy: percentage of cases achieving a complete response to treatment.

- □

Secondary efficacy: percentage of cases achieving a complete response to treatment following identification of local tumour progression.

- □

Overall survival: length of patient survival, regardless of cause of death.

- □

Cancer-specific survival: length of patient survival when cause of death is related to the renal tumour.

- □

Time-to-tumour progression: time interval between the ablation procedure and disease progression.

Student’s t-test was used to compare the means of the quantitative variables in relation to efficacy, tumour recurrence and complications of the technique. Student’s paired t-test was used to compare creatinine levels prior to and one year following the ablation. Contingency tables were developed and χ2 test was used to contrast the qualitative variables. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to express disease-free survival rate in a graph. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the relationship between the different factors and the occurrence of complications, incomplete ablation or recurrence. All p values obtained were based on bilateral analysis. For all the tests, any p value less than 0.05 was considered significant. The Stata 17 statistics program was used for all analyses.

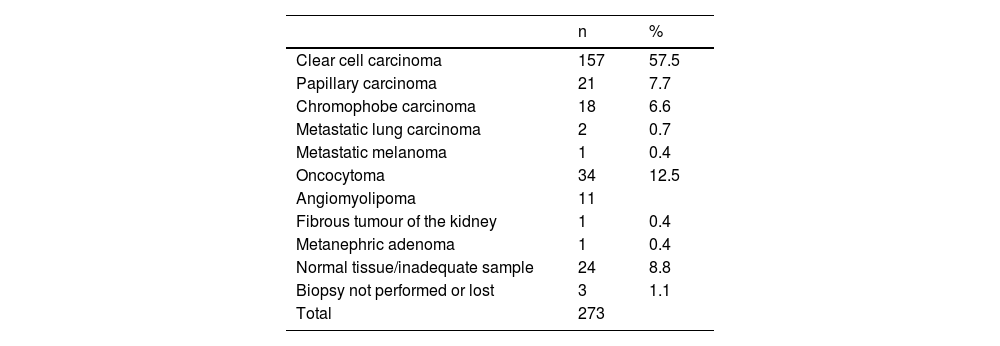

ResultsIn total 305 ablations were performed on 273 lesions in 238 patients (162 men and 76 women). At the time of ablation, the patients were aged between 37 and 95 years (mean 71.29). The lesion biopsy results are set out in Table 1.

Results of lesion biopsies.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Clear cell carcinoma | 157 | 57.5 |

| Papillary carcinoma | 21 | 7.7 |

| Chromophobe carcinoma | 18 | 6.6 |

| Metastatic lung carcinoma | 2 | 0.7 |

| Metastatic melanoma | 1 | 0.4 |

| Oncocytoma | 34 | 12.5 |

| Angiomyolipoma | 11 | |

| Fibrous tumour of the kidney | 1 | 0.4 |

| Metanephric adenoma | 1 | 0.4 |

| Normal tissue/inadequate sample | 24 | 8.8 |

| Biopsy not performed or lost | 3 | 1.1 |

| Total | 273 |

Three of the ablations were performed on residual tumour after a patient had undergone a nephrectomy and will therefore not be included in the following analyses.

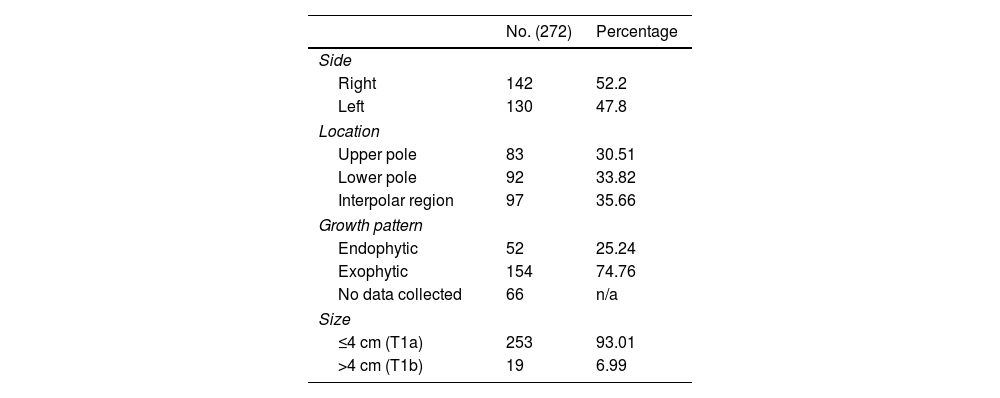

The morphological characteristics of the lesions are set out in Table 2. A total of 47.8% of the lesions were located in the left kidney, and 52.2% in the right; 30.51% were located in the upper pole, 33.82% in the lower pole and 35.66% crossed the polar line. Seventy-five percent were exophytic lesions and 25% were not. The size of the nodules in each treatment varied between 0.7 and 5.25 cm (mean 2.57), with 253 measuring 4 cm or less (T1a) and 19 measuring over 4 cm (T1b).

For each lesion treated, the American Society of Anaesthesiology (ASA) Physical Status Classification of the patient's present physical condition was assessed. Two patients were classified as ASA grade 1; 179 as ASA grade 2; 122 as ASA grade 3 and 2 as ASA grade 4. Blood creatinine prior to treatment ranged from 0.36 to 6.03 mg/dL (mean 1.14, SD 0.62). A year after treatment it ranged from 0.4–8.2 mg/dL (mean 1.30, SD 0.88). The difference was statistically significant (p < 0.0001).

Hydrodissection was used in 30 procedures. A catheter for ureteral irrigation was used in five procedures.

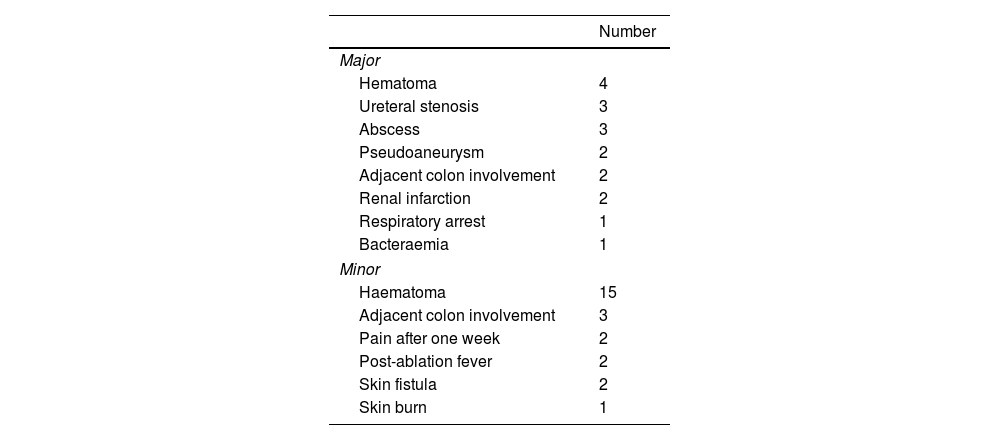

ComplicationsComplications occurred in 40 of the ablations (13.25%). In 15 (4.97%) of these major complications occurred and in 25 (8.28%) minor complications occurred (Table 3). One of the patients died as a consequence of a perinephric infection following treatment.

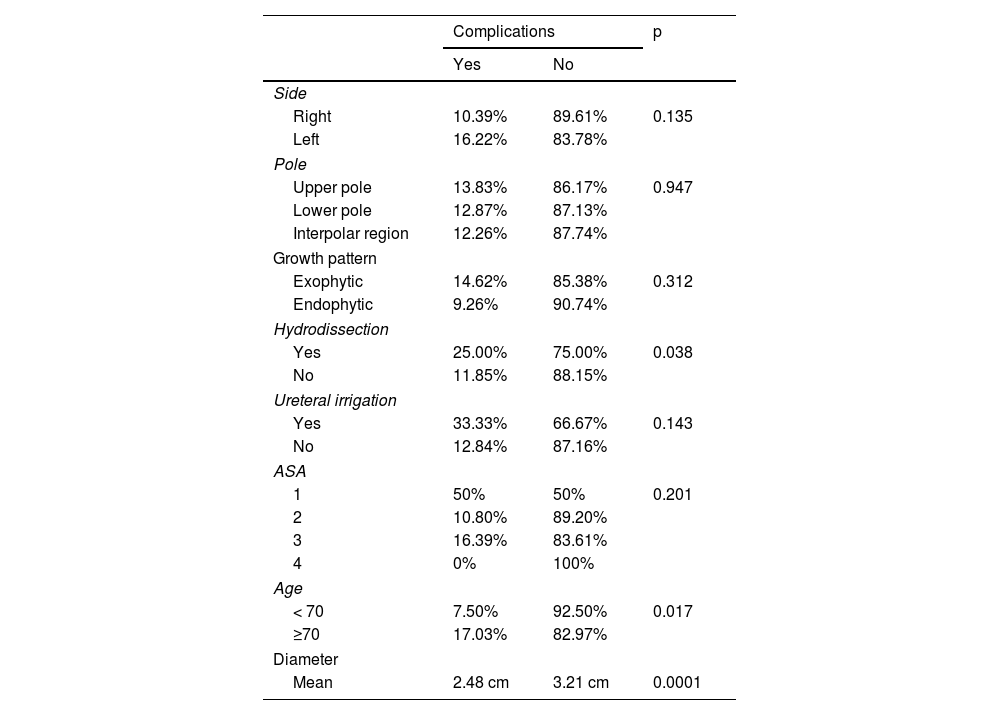

The mean age of patients who suffered complications (75.13) was greater than the mean of those who did not (70.82), and this difference was significant (p = 0.013). We also observed a highly significant difference (p < 0.0001) in the diameter of the lesions between the cases with complications (mean of 2.48 cm) and those that did not experience complications (mean 3.21 cm). No significant difference was observed in creatinine levels prior to ablation between patients who experienced complications and those who did not (p = 0.552).

The relationship between other qualitative variables and the occurrence of complications are set out in Table 4. The use of hydrodissection during the procedure and being over 70 years of age were the only factors associated with complications. Logistic regression, however, demonstrated that age was the only variable directly associated with complications, while hydrodissection was associated with age.

Association of multiple variables with the occurrence of complications.

| Complications | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Side | |||

| Right | 10.39% | 89.61% | 0.135 |

| Left | 16.22% | 83.78% | |

| Pole | |||

| Upper pole | 13.83% | 86.17% | 0.947 |

| Lower pole | 12.87% | 87.13% | |

| Interpolar region | 12.26% | 87.74% | |

| Growth pattern | |||

| Exophytic | 14.62% | 85.38% | 0.312 |

| Endophytic | 9.26% | 90.74% | |

| Hydrodissection | |||

| Yes | 25.00% | 75.00% | 0.038 |

| No | 11.85% | 88.15% | |

| Ureteral irrigation | |||

| Yes | 33.33% | 66.67% | 0.143 |

| No | 12.84% | 87.16% | |

| ASA | |||

| 1 | 50% | 50% | 0.201 |

| 2 | 10.80% | 89.20% | |

| 3 | 16.39% | 83.61% | |

| 4 | 0% | 100% | |

| Age | |||

| < 70 | 7.50% | 92.50% | 0.017 |

| ≥70 | 17.03% | 82.97% | |

| Diameter | |||

| Mean | 2.48 cm | 3.21 cm | 0.0001 |

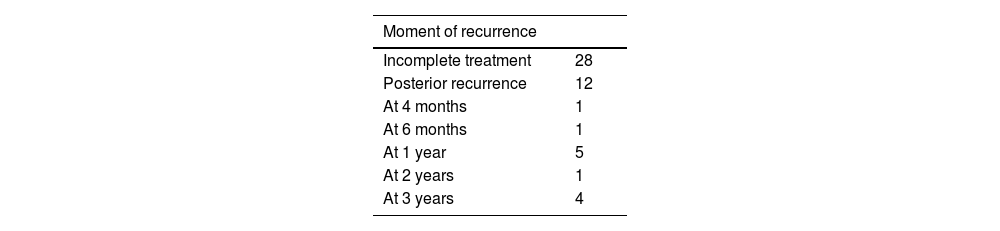

In three cases no follow-up CT was performed at one month (due to nephrectomy in one case and death in two), so they are excluded from the analysis. In 23 lesions, complete ablation was not initially achieved. The treatment was repeated once in 16 of these (Fig. 1), two of which were never successful. Ablation was repeated twice (after initial failure) in two cases, one of which was not successful. This makes a total of 28 incomplete ablations and 10 treatment failures (Table 5). Initial technical success was, therefore 90.63% (271 out of 299) and primary efficacy was 96.28% (259 out of 269).

Incomplete ablation and successful retreatment. (A) Computed tomography (CT) of 3 cm diameter renal carcinoma in left kidney. (B) In the contrast-enhanced ultrasound performed 24 h after the ablation an area of residual uptake is identified (arrows). (C) In the CT performed one month after the ablation an area of residual tumour is confirmed. (D) After further ablation, no uptake in the tumour is observed.

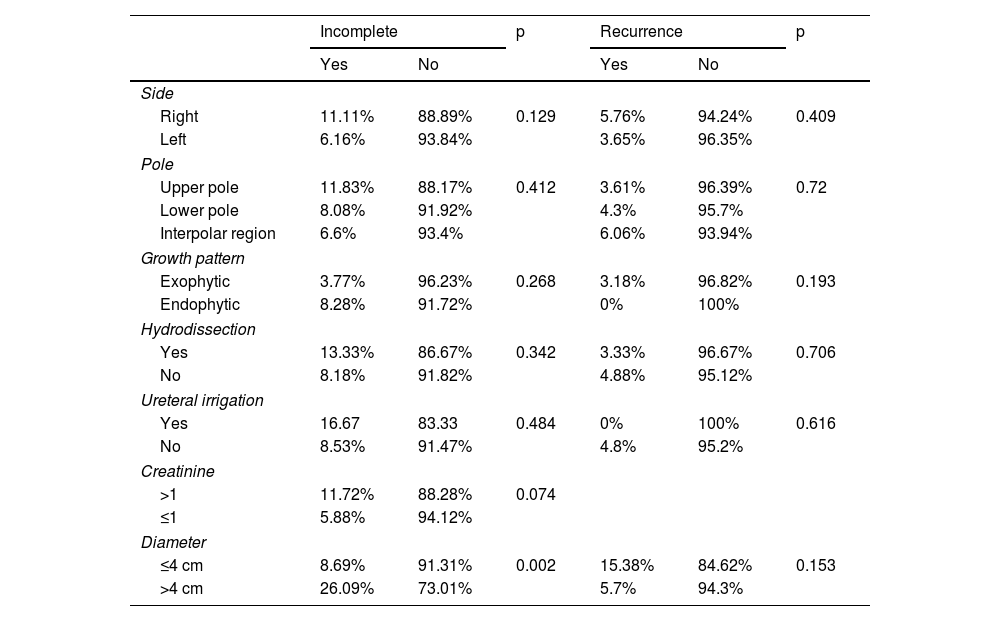

No significant differences were observed between initial complete and incomplete ablations as regards the side of the kidney or renal pole in which the treated lesion was located, endo/exophytic growth pattern, the use or not of hydrodissection or a catheter for ureteral irrigation, or creatinine levels above or below 1 mg/dL. However, lesions greater than 4 cm in diameter were significantly more likely to result in incomplete ablations (p = 0.002) and the mean diameter of the lesions for which complete ablation was not achieved (3.15 cm) was significantly greater (p = 0.003) than those treated successfully (2.52 cm) (Table 6).

Association of multiple variables with incomplete ablation or late recurrence.

| Incomplete | p | Recurrence | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |||

| Side | ||||||

| Right | 11.11% | 88.89% | 0.129 | 5.76% | 94.24% | 0.409 |

| Left | 6.16% | 93.84% | 3.65% | 96.35% | ||

| Pole | ||||||

| Upper pole | 11.83% | 88.17% | 0.412 | 3.61% | 96.39% | 0.72 |

| Lower pole | 8.08% | 91.92% | 4.3% | 95.7% | ||

| Interpolar region | 6.6% | 93.4% | 6.06% | 93.94% | ||

| Growth pattern | ||||||

| Exophytic | 3.77% | 96.23% | 0.268 | 3.18% | 96.82% | 0.193 |

| Endophytic | 8.28% | 91.72% | 0% | 100% | ||

| Hydrodissection | ||||||

| Yes | 13.33% | 86.67% | 0.342 | 3.33% | 96.67% | 0.706 |

| No | 8.18% | 91.82% | 4.88% | 95.12% | ||

| Ureteral irrigation | ||||||

| Yes | 16.67 | 83.33 | 0.484 | 0% | 100% | 0.616 |

| No | 8.53% | 91.47% | 4.8% | 95.2% | ||

| Creatinine | ||||||

| >1 | 11.72% | 88.28% | 0.074 | |||

| ≤1 | 5.88% | 94.12% | ||||

| Diameter | ||||||

| ≤4 cm | 8.69% | 91.31% | 0.002 | 15.38% | 84.62% | 0.153 |

| >4 cm | 26.09% | 73.01% | 5.7% | 94.3% | ||

Post-treatment recurrence occurred in 11 lesions (4.02%), one of which recurred twice. They recurred at four months, six months, one year (four cases), two years and three years (four cases). Eight of these were retreated successfully, although one recurred after one year, which was treated again, this time successfully. All together, in the end, the tumour was not eradicated in 13 lesions, which gives a secondary efficacy of 95.28% (259 out of 269) (Table 5).

No significant differences were observed between the presence or absence of late recurrence regards the side of the kidney or renal pole in which the treated lesion was located, endo/exophytic growth pattern, use or not of hydrodissection or of a ureteral catheter for irrigation, tumour measuring less or more than 4 cm or creatinine levels above or below 1 mg/dL (Table 6). However, the mean diameter of the lesions that recurred (3.16 cm) was significantly greater (p = 0.02) than that of the lesions that did not (2.5 cm).

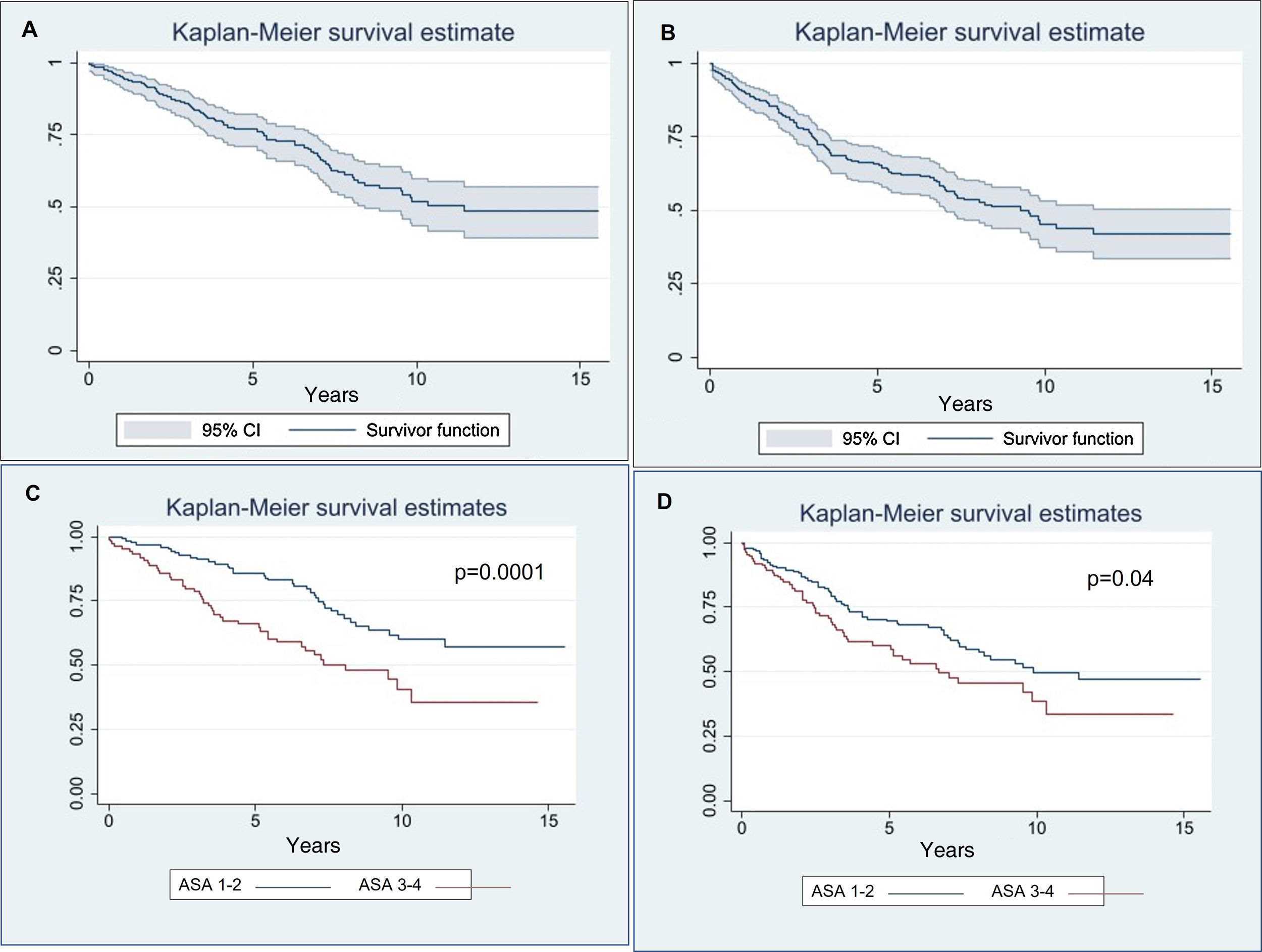

Disease-free survivalThe disease-free survival rate (Fig. 2) was 90.49% at one year (confidence interval (CI): 0.863–0.935), 65.65% at five years (CI: 0.593–0.713) and 45.37% at ten years (CI: 0.374–0.53).

No significant differences were observed according to age (p = 0.066), endophytic or exophytic growth pattern (p = 0.68) or the malignant or benign nature of the treated lesion (p = 0.27). However, the risk of mortality/recurrence increased in patients with creatinine levels > 1 (p = 0.0001) prior to treatment or ASA > 2 (p = 0.04) (Fig. 2).

Overall survivalOnly four patients died of metastatic spread of renal carcinoma, but all four patients had undergone nephrectomies to treat carcinoma prior to the ablation. The overall survival rate (Fig. 2) was 95.26% at one year (CI: 0.916–0.974), 77.01% at five years (CI: 0.708–0.821) and 51.78% at ten years (CI: 0.431–0.598).

No significant differences were observed according to age (p = 0.13), endo/exophytic growth pattern (p = 0.22) or malignant/benign nature of the treated lesion (p = 0.32). However, the risk of mortality increased in patients with creatinine values > 1 (p = 0.05) or ASA grade > 2 (p = 0.0001) (Fig. 2).

DiscussionThermal ablation has found a place among therapeutic alternatives for renal cancer,2 although it is yet to be accepted as a fully effective alternative in urological clinical guidelines.4 This study provides further evidence as to the high efficacy and safety of the technique, and that it obtains similar outcomes to that of partial nephrectomy, having demonstrated over 95% efficacy in patients the majority of whom were considered unsuitable for surgical intervention.

In our case series, survival rate at one year was very high (95%). This fell considerably by ten years post-treatment, but renal carcinoma was the cause of death in only four cases, all of whom had undergone surgery for previous renal carcinomas. The age of the patients, with a mean of 71, means this is to be expected. It should be noted that survival in patients with malignant lesions did not differ from that of patients with benign lesions, which indicates that ablation evened out survival rates between patients with carcinoma and those without.

Many series that compare ablation with other treatments have reported survival outcomes similar to or slightly below that of partial nephrectomy, and clearly better than active surveillance.3,6,8–11,14,16–24,31 The problem with comparative studies is that case series are never the same, as patients treated with ablation tend to be old or have significant comorbidities. In fact, the only factors that influenced survival rates were creatinine levels and pre-treatment comorbidity as classified by the ASA grading system. Factors associated with the morphology or size of the treated lesion had no impact.

Various nephrometry scoring systems (RENAL, PADUA, ABLATE, etc.)25–29 based on the morphological characteristics of the lesion have been proposed, to predict the risk of complications or treatment failure prior to an ablation. In our series, none of the variables used to make up these scoring systems were significantly associated with complications, except size, which was significantly associated counterintuitively to that proposed by the systems (bigger, less probability of complications). Only hydrodissection (usually performed when the tumour is located in proximity to digestive structures) showed any association, but logistic regression demonstrated that it was actually associated with age, possibly because constipation and colon diameter tend to increase with age. The age of the patient was the only factor clearly associated with the risk of complications.

Only size was shown to be associated with the risk of incomplete ablation, as well as with tumour recurrence. It is relevant to note that in our previous publication which looked at the first cases in this series,31 we observed a link between the endo/exophytic growth pattern of the lesion and incomplete ablation that we no longer observe. This suggests that experience can resolve problems caused by tumour morphology.

Our findings corroborate those of other studies that also found that nephrometry scoring systems were not helpful in terms of predicting adverse outcomes.7,29

One of the often-mentioned advantages of ablation in comparison with nephrectomy—including partial nephrectomy—is that it has nearly no impact on renal function.3,6,9–11,19,21,22 In our case series, however, we have identified a significant, though moderate, increase in blood creatinine, which indicates that ablation also causes some damage to renal function.

This study has various limitations: it is retrospective, there is no comparison group, and it includes a small number of procedures performed with microwaves and some patients with benign lesions or with no pathological diagnosis. However, this provides an overview of the practical application of the technique in a more real clinical context.

ConclusionsPercutaneous ablation of renal tumours is a highly effective technique, which improves the prognosis of renal carcinomas after treatment to match that of benign lesions. Complications are very rare and both complications and survival rate are associated with age and the general health of the patient prior to treatment. Risk of recurrence and incomplete treatment is very low and is associated only with the size of the tumour.

Authors contributions- 1.

Research coordinator: J.LC.

- 2.

Development of study concept: J.LC.

- 3.

Study design: J.L.C

- 4.

Data collection: J.L.C., R.Z., I.K.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: J.L.C., R.Z., I.K.

- 6.

Statistical analysis: J.L.C.

- 7.

Literature search: J.L.C., R.Z., I.K.

- 8.

Writing of article: J.L.C.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: J.L.C., R.Z., I.K.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: J.L.C., R.Z., I.K.

This research has not received funding support from public sector agencies, the business sector or any non-profit organisations.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

To Estibaliz Unibaso Rodríguez and Iratxe Urreta Barallobre, without whose unquantifiable support this article would never have been completed.