Optic nerve enhancement is a sign seen in different disease states; however, perineural enhancement is less common. This article presents the case of a patient with bilateral amaurosis in whom the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis was suggested by perineural enhancement on orbital magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and confirmed by biopsy of the temporal artery.

The clinical presentation of giant cell arteritis is occasionally nonspecific; patients can have visual symptoms, even blindness if the branches of the ophthalmic artery are affected; in these cases, orbital MRI can be very useful for early diagnosis. Although the MRI findings are uncommon, distinct patterns of enhancement have been reported, the most characteristic of which is perineural enhancement. The pattern of optic nerve involvement is relatively unknown, but important because it orients the diagnosis of a disease that can lead to permanent blindness.

La captación del nervio óptico es un signo visualizado en diferentes patologías; sin embargo, el realce perineural es menos frecuente. Se presenta el caso de una paciente con clínica de amaurosis bilateral en la que se sugirió el diagnóstico de arteritis de células gigantes por la captación perineural detectada en una resonancia magnética (RM) orbitaria, que se confirmó por biopsia de la arteria temporal.

La clínica es, en ocasiones, inespecífica y puede presentarse con síntomas visuales, incluso ceguera si afecta a ramas de la arteria oftálmica; en estos casos, la RM orbitaria puede ser de gran utilidad para un diagnóstico precoz. Si bien los hallazgos por RM son poco frecuentes, se han descrito distintos patrones de captación de contraste, entre los que el realce perineural es el más característico. Este patrón de afectación del nervio óptico es poco conocido pero relevante, pues orienta al diagnóstico de una patología que puede conducir a la ceguera permanente.

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is the most common primary vasculitis and can present with very non-specific symptoms. One of the most devastating and uncommon manifestations is blindness due to ischaemic optic neuropathy. Prompt diagnosis and treatment are decisive. Imaging tests are not required when the clinical symptoms are characteristic, but can be used when the diagnosis is unclear. In our case, there was bilateral perineural enhancement affecting the sheath of the optic nerves and adjacent intraconal fatty tissue. Other less characteristic enhancements described in the scientific literature will also be described, highlighting the importance of orbital magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), specifically of the post-contrast T1 sequence with fat saturation.

Case presentation62-year old woman with history of mild alcoholism and type 2 diabetes mellitus, who consulted for amaurosis, initially of the right eye and subsequently of the left, together with retro-ocular pain. She also reported bilateral shoulder pain in the last 6 months, diagnosed with fibromyalgia. She did not experience headache.

The physical examination revealed bilateral amaurosis with a visual acuity of 0 and non-reactive pupils. The fundus examination of the eye showed bilateral papilledema. The blood test showed hyperglycaemia and a mild increase in the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (39 mm/h). Lumbar punctured was performed, which showed no alterations.

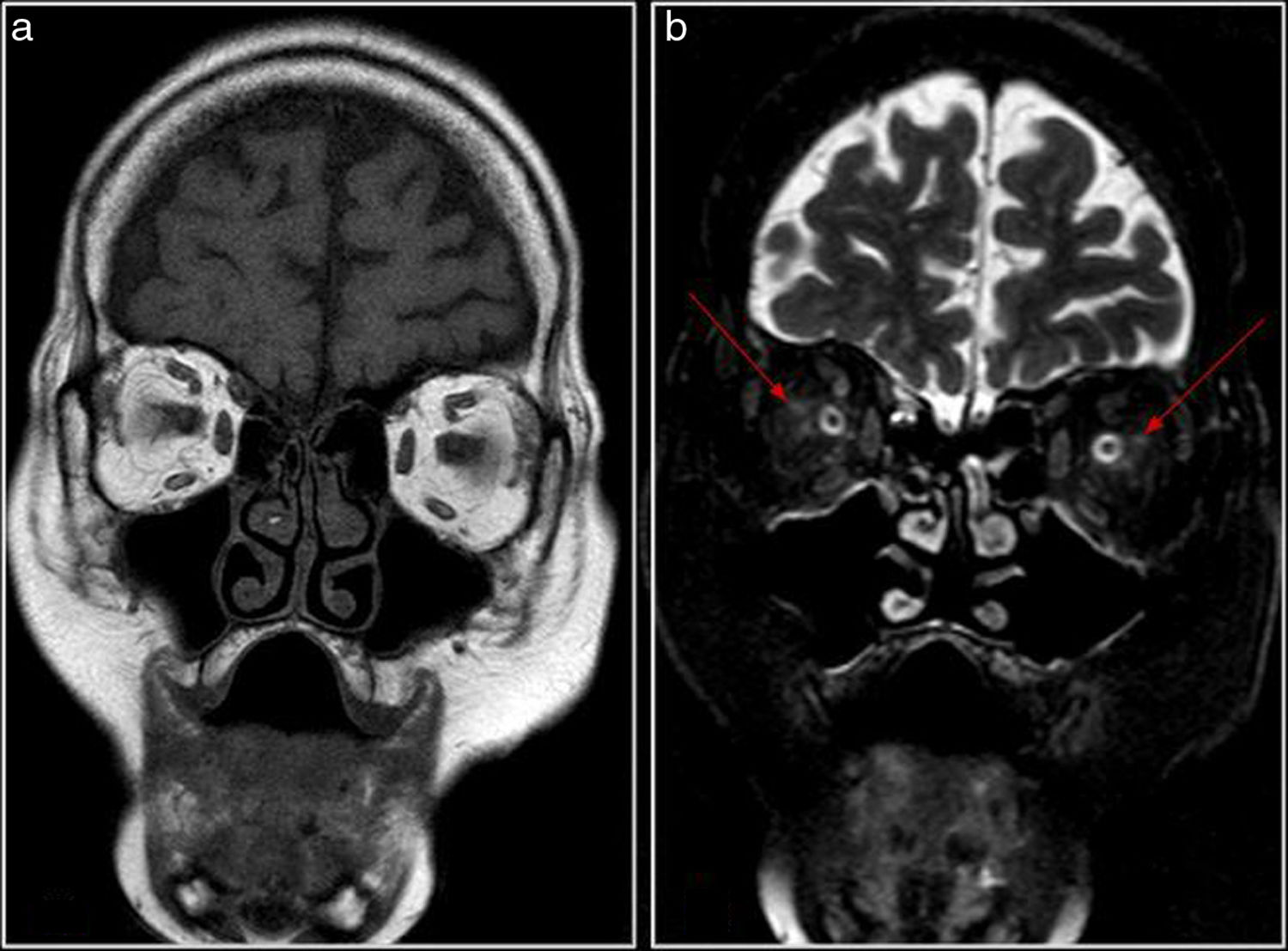

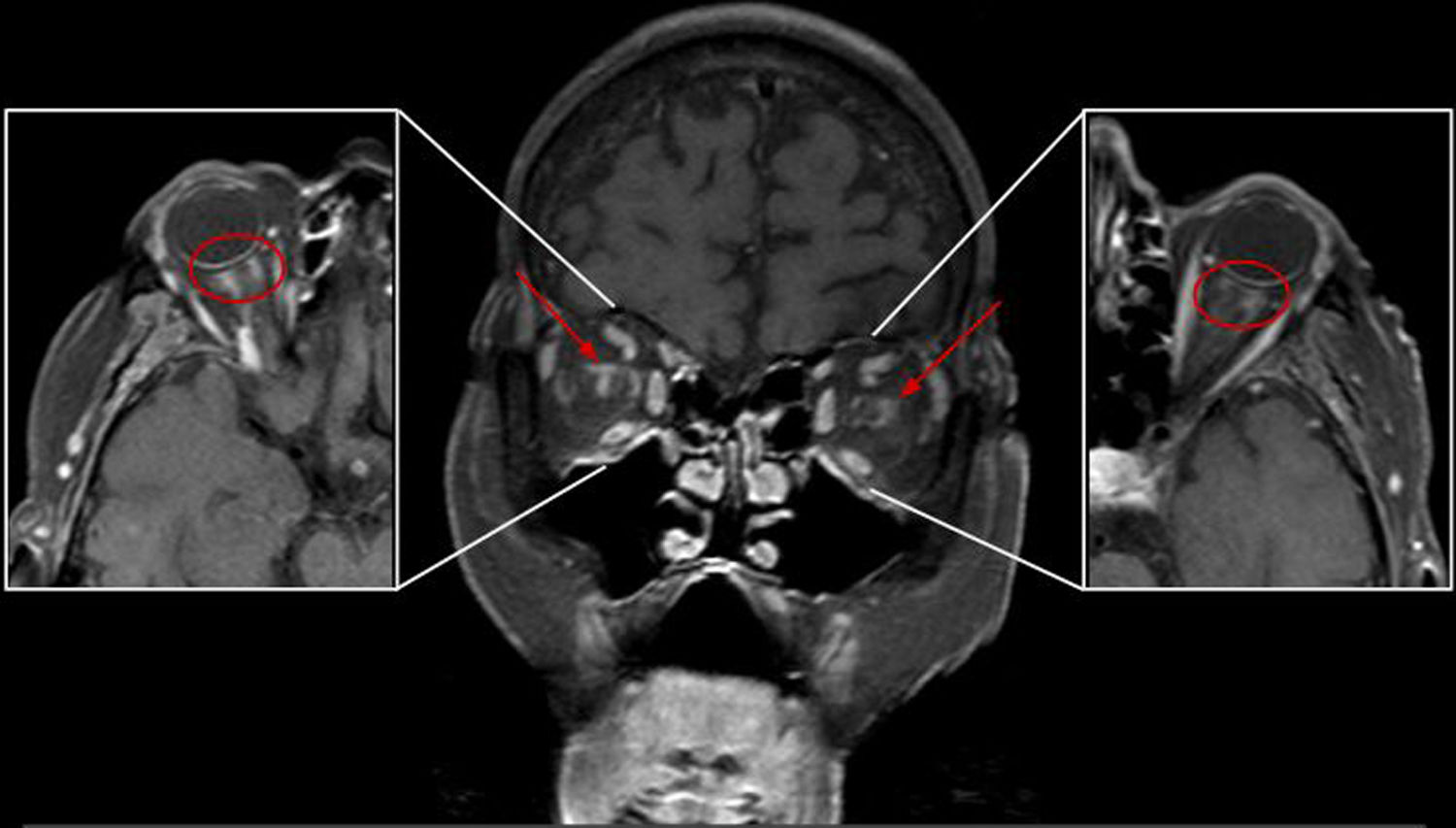

A head and orbital MRI (Philips Intera 1.5 T) showed mild hypoxycoischaemic leukoencephalopathy. After administering gadolinium, the T1 sequences with fat saturation showed poorly delimited perineural orbital enhancement in the sheath of both optic nerves and adjacent retrobulbar fatty tissue (Figs. 1 and 2). This finding has been described in GCA with visual involvement, so in the patient's context, with no evidence of other inflammatory or neoplastic diseases, this diagnosis was suggested.

In view of the suspected bilateral anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (AION) due to GCA, treatment was started with boluses of methylprednisone and acetylsalicylic acid, pending the result of the temporal artery biopsy (gold standard). The histological study confirmed the diagnosis of GCA.

DiscussionGCA is systemic granulomatous vasculitis affecting medium-large arteries. The most commonly affected branches are the outer carotid artery and the temporal artery. Visual symptoms due to ischaemic optic neuropathy are one of the most feared complications of GCA and can be the first sign of the disease. Ischaemic optic neuropathy is a disease secondary to the interruption of the blood flow in the ophthalmic artery and its branches, leading to different degrees of blindness. It can be caused by different conditions, and approximately 10% of patients present arteritic origin due to GCA.

Neuroimaging is not generally necessary in GCA, but in patients with atypical presentation and visual symptoms, it has been shown that MRI can play an important role in its diagnosis.

MRI in GCA, as well as ruling out demyelinating causes, lesions that compress the optic nerve and infectious diseases that can worsen with corticosteroid treatment, such as fungal sinusitis, can reveal orbital lesions indicative of AION, the most common ocular symptom in GCA, affecting the region near the junction of the optic nerve with the eyeball, often bilaterally:

- •

The most frequently described finding (less than 10 cases in the literature) is perineural enhancement affecting the sheath of the optic nerve and perineural fat (Figs. 1 and 2), suggesting inflammatory changes: optic perineuritis.1–4 Its extension to the chiasma has occasionally been described (posterior ischaemic optic neuropathy.5,6 In a patient who underwent perineural biopsy, fibroadipose tissue was confirmed, with multiple arteries with mural inflammation from lymphocytes and giant cells.7

- •

Optic nerve enhancement, generally tenuous, has been described less frequently, associated with hypersignal in STIR (short tau inversion recovery). This finding has also been occasionally described in non-arteritic ischaemic optic neuropathy.8

- •

Non-specific orbital uptake (muscular, diffuse) has been described in some articles.5

- •

Spot-shaped uptake on the head of the optic nerve (the central bright spot sign) was described in an ischaemic optic neuropathy series, with arteritic neuropathy in nearly all the patients, and non-arteritic in only a few.9 This finding has probably not been described more often due to the characteristics of the 3 T MRI study, with a high resolution 3DT1 sequence.

Moreover, mural thickening and uptake of the temporal arteries, and even the ophthalmic arteries, can be detected in GCA.

The differential diagnosis of perineural uptake would be with inflammatory disease (non-specific inflammatory optic perineuritis, sarcoidosis, Wegener’s granulomatosis), infectious disease (syphilis, herpes zoster, tuberculosis), tumour (metastasis, lymphoma/leukaemia, meningioma) or autoimmune disease (optic neuritis associated with anti-MOG Ab10).

GCA findings in MRI are uncommon, non-specific and variable, which can delay diagnosis and treatment. This condition can, less frequently, cause visual symptoms from other vascular causes (central retinal artery occlusion, cilioretinal artery occlusion, occipital lobe infarction).7 However, high resolution orbital MRI, including STIR, T2 and T1 sequences, fat saturation and intravenous gadolinium, can show perineural uptake in a characteristic AION location which, in an appropriate clinical context, supports an early diagnosis of GCA.

ConclusionsGCA is systemic vasculitis that can cause permanent blindness if early diagnosis and treatment is not established. Although imaging tests are generally unnecessary in typical cases, orbital MRI can help target the diagnosis in patients presenting optic neuropathy of unknown cause.

FundingThis review received no specific grants from public agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit organisations.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Serrano Alcalá E, Grivé Isern E, Díez Borras L, Salaya Díaz JT. Resonancia magnética orbitaria para desenmascarar arteritis de células gigantes. Radiología. 2020;62:160–163.