The appearance of new-onset liver lesions is frequent during imaging follow-up of oncological patients. Most of these lesions will be metastases. But in the presence of atypical radiological findings, there are other diagnoses to consider. Hepatic abscesses, focal nodular hyperplasia-like in patients treated with platinum salts, or hepatocarcinoma in cirrhotic patients are examples of lesions that may appear in the imaging follow-up and should not be confused with metastases. It is essential to establish the nature of the lesion as this will determine the therapeutic management and might avoid unnecessary invasive procedures. The evaluation of previous radiological studies and the global vision of the patient will be primordial. While liver MRI is mainly the indicated imaging technique for these cases, sometimes a biopsy will be unavoidable. In this article, we will discuss through clinical cases some new-onset liver lesions in oncological patients that generated diagnostic doubts and will explain how to orient the diagnosis.

Durante los controles radiológicos del paciente oncológico, es frecuente la aparición de lesiones hepáticas. Aunque la mayoría suelen ser metástasis, ante hallazgos radiológicos atípicos existen otros diagnósticos a tener en cuenta. Los abscesos hepáticos, la hiperplasia nodular focal-like en los pacientes tratados con sales de platino o el hepatocarcinoma en pacientes cirróticos son ejemplos de lesiones que pueden aparecer en el seguimiento estos pacientes y que no deben ser confundidas con metástasis. Es indispensable establecer la naturaleza de la lesión ya que de ello dependerá el manejo terapéutico y evitará procedimientos invasivos innecesarios. Los estudios radiológicos previos junto a la visión global del enfermo serán primordiales y, aunque la RM hepática será en general la prueba indicada, en ocasiones la biopsia será inevitable. En este artículo trataremos mediante casos clínicos algunas lesiones hepáticas de nueva aparición en el paciente oncológico que pueden generar dudas diagnósticas y cómo orientar el diagnóstico.

Radiological follow-up in oncology patients increases the early detection of new-onset liver lesions, allowing for prompt treatment modification, thereby improving survival rates.1 While metastasis is the primary suspicion, radiologists need to be familiar with alternative diagnoses for cases with atypical findings. Establishing the nature of the lesion is crucial, as this affects therapeutic management and can prevent unnecessary invasive procedures. Key to diagnosis is a comprehensive evaluation of the patient, which includes their clinical history, primary tumour type, previous treatments and a thorough review of prior imaging studies.

Although most of these lesions are detected during computed tomography (CT) follow-up, CT alone is rarely sufficient for a definitive diagnosis when findings are atypical for metastasis. In such cases, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the liver is generally recommended. If MRI does not provide a conclusive diagnosis, a biopsy of the lesion is necessary.

We will use clinical case studies to explore various new-onset liver lesions or pseudolesions identified during oncological follow-up that may pose diagnostic challenges.

Malignant lesionsMetastasisMetastasis is the most common type of malignant liver tumour,2 making it the primary diagnostic suspicion in oncology patients.

On imaging, metastases are typically hypovascular with peripheral ring enhancement. However, some may be hypervascular (for example, thyroid, neuroendocrine, and clear cell renal carcinomas),2 and others may appear cystic due to necrosis or mucin content. MRI is the most sensitive modality for their detection,3 with metastases appearing hypointense on T1-weighted sequences, mildly hyperintense on T2-weighted, and typically demonstrating diffusion restriction.2

When a new-onset liver lesion with unequivocal radiological features of metastasis is identified, the following factors should be considered:

Does the primary tumour typically metastasise to the liver? What was the initial stage of the tumour in the surgical specimen? For primary tumours that rarely metastasise to the liver or those diagnosed at very early surgical stages with a low likelihood of distant spread, the appearance of liver metastases should raise suspicion of another undiagnosed primary tumour (Fig. 1).

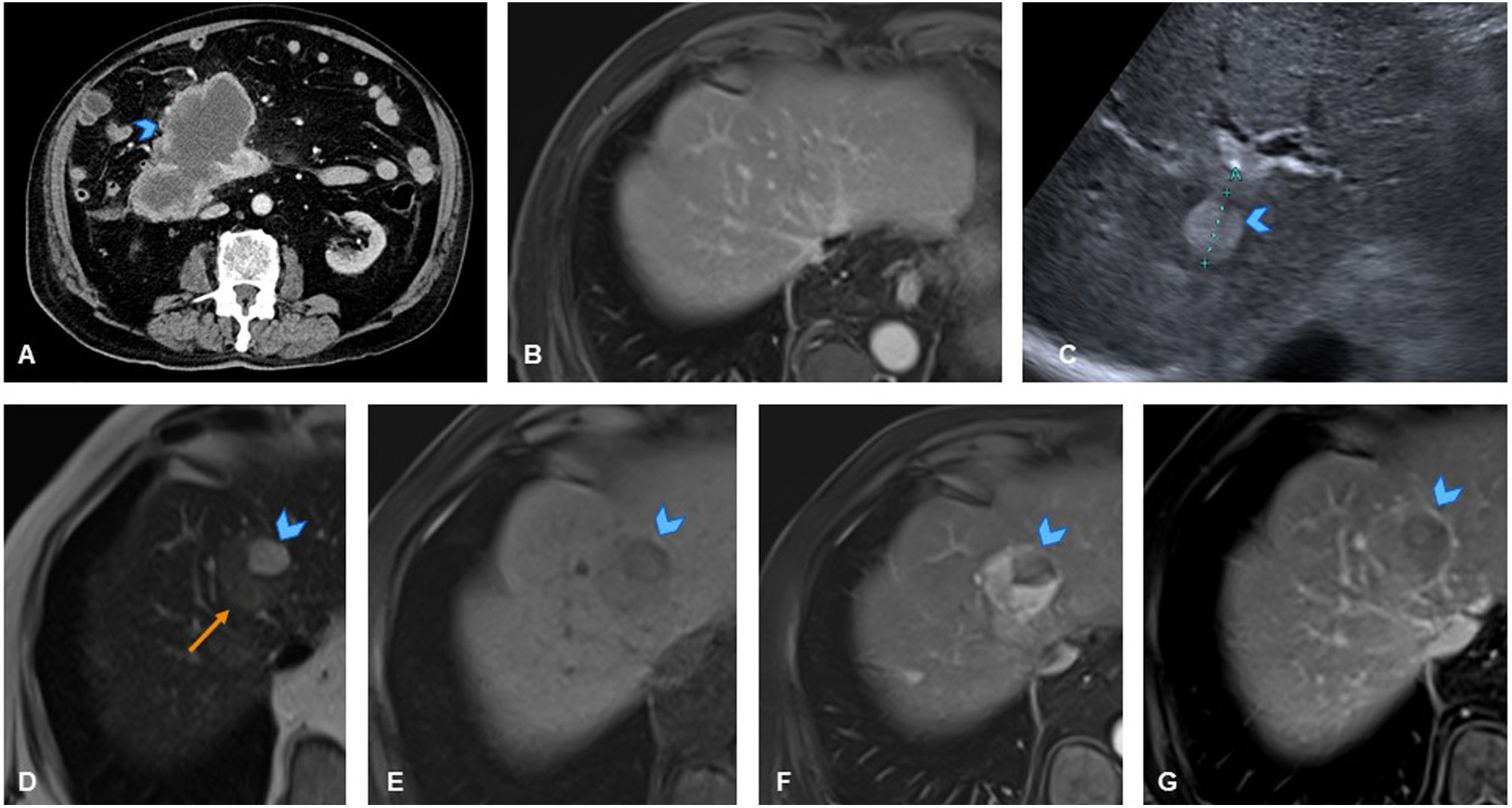

A 73-year-old man with history of well-differentiated appendiceal neuroendocrine tumour (T1N0M0) diagnosed after appendiceal phlegmon. (A) Axial CT slice showing ill-defined mass with internal calcification (arrowhead), consistent with appendiceal phlegmon. Follow-up CT revealed signs of metastatic involvement. (B) Follow-up axial CT slice in portal phase revealing space-occupying lesion in hepatic dome (arrowhead). (C) Axial CT slice with bone window revealing lytic lesion in left iliac wing, consistent with bone metastasis (arrowhead). (D) Axial CT slice at lower thoracic level showing solid lesion consistent with pleural implant (arrowhead). Chest CT scan (E) performed to rule out neoplasm, revealing right apical primary tumour (arrowhead) with mediastinal lymphadenopathy (orange arrow). Biopsy of the bone lesion confirmed metastasis from poorly differentiated non-small cell lung carcinoma.

Note: In cases of apparent liver metastasis where the primary tumour has a low probability of metastasising to the liver, the possibility of another unknown primary tumour should be considered.

Primary tumoursOncology patients, like the general population, may develop primary malignant liver tumours, most commonly a hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) or intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.4

HCCs are the most common primary liver tumours, with liver cirrhosis being the most significant risk factor.4 If an oncology patient has diagnosed or imaging-suggested chronic liver disease, HCC should be considered in the differential diagnosis if a new-onset liver lesion is detected. Additionally, patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection can develop HCCs even in the absence of cirrhosis.4,5

Typical HCCs demonstrate arterial phase enhancement with washout in the portal/venous and/or delayed phases. They may also have a hyperenhancing peripheral capsule and contain fat, necrosis, and/or haemorrhage.6 The presence of fat is useful in differentiating HCCs from metastases, as metastases rarely contain fat (exceptions include metastases from liposarcoma, malignant germ cell tumours and renal cell carcinoma).7 Furthermore, portal vein thrombosis8 and elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein9 are more characteristic of HCCs. In general, if cirrhosis is present and the lesion exhibits a typical enhancement pattern, it is easily distinguishable from hypovascular metastases (Fig. 2). However, if a patient has a primary tumour that produces hypervascular metastases or in cases of atypical HCCs, differentiation from metastasis through imaging will be difficult. In these cases, the presence of fat, alpha-fetoprotein elevation, or portal vein thrombosis can aid diagnosis but biopsy is generally required.

An 85-year-old man with history of liver cirrhosis and gastrointestinal stromal tumour of the duodenum. (A) Axial CT slice showing primary duodenal tumour, treated surgically. Following surgery, patient was disease-free. Follow-up ultrasound in 2017 identified suspicious liver nodule. (B) Axial slice from liver MRI in staging scan showing no focal liver lesions. (C) Follow-up ultrasound in 2021 revealing 15mm hyperechoic nodule in segment VII (arrowhead). MRI confirmed multiple liver lesions, with one prominent lesion in segment IVa. (D) Slice from T2-weighted sequence of liver MRI showing mildly hyperintense appearance of the solid component of the lesion (orange arrow) with markedly hyperintense cystic-necrotic changes on T2 (arrowhead). (E) Slice from T1-weighted sequence of liver MRI showing hypointense appearance of the same lesion (arrowhead). (F, G) Slices from dynamic MRI study of the liver showing intense enhancement of lesion in arterial phase, except for cystic-necrotic portion (F, arrowhead), with washout in delayed phase and thin persistent peripheral rim of enhancement, indicating a capsule (G, arrowhead). Findings associated with significant increase in serum alpha-fetoprotein levels. Despite history of gastrointestinal stromal tumour of the duodenum, typical radiological findings suggested multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma as primary diagnosis, confirmed by liver biopsy.

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas are typically nodular lesions with a variable degree of peripheral contrast uptake which, unlike metastases, exhibit gradual centripetal enhancement in the later phases, with its progression influenced by the extent of central fibrosis.10 In many cases, this enhancement pattern may not be present. Additionally, it is important to consider that routine CT follow-ups in oncology patients do not generally include a delayed equilibrium phase, making differentiation from metastases very challenging. Imaging can show capsular retraction due to fibrosis and dilation of the intrahepatic bile ducts distal to the lesion. While these findings are useful, they are not exclusive to cholangiocarcinomas2,10 (Fig. 3).

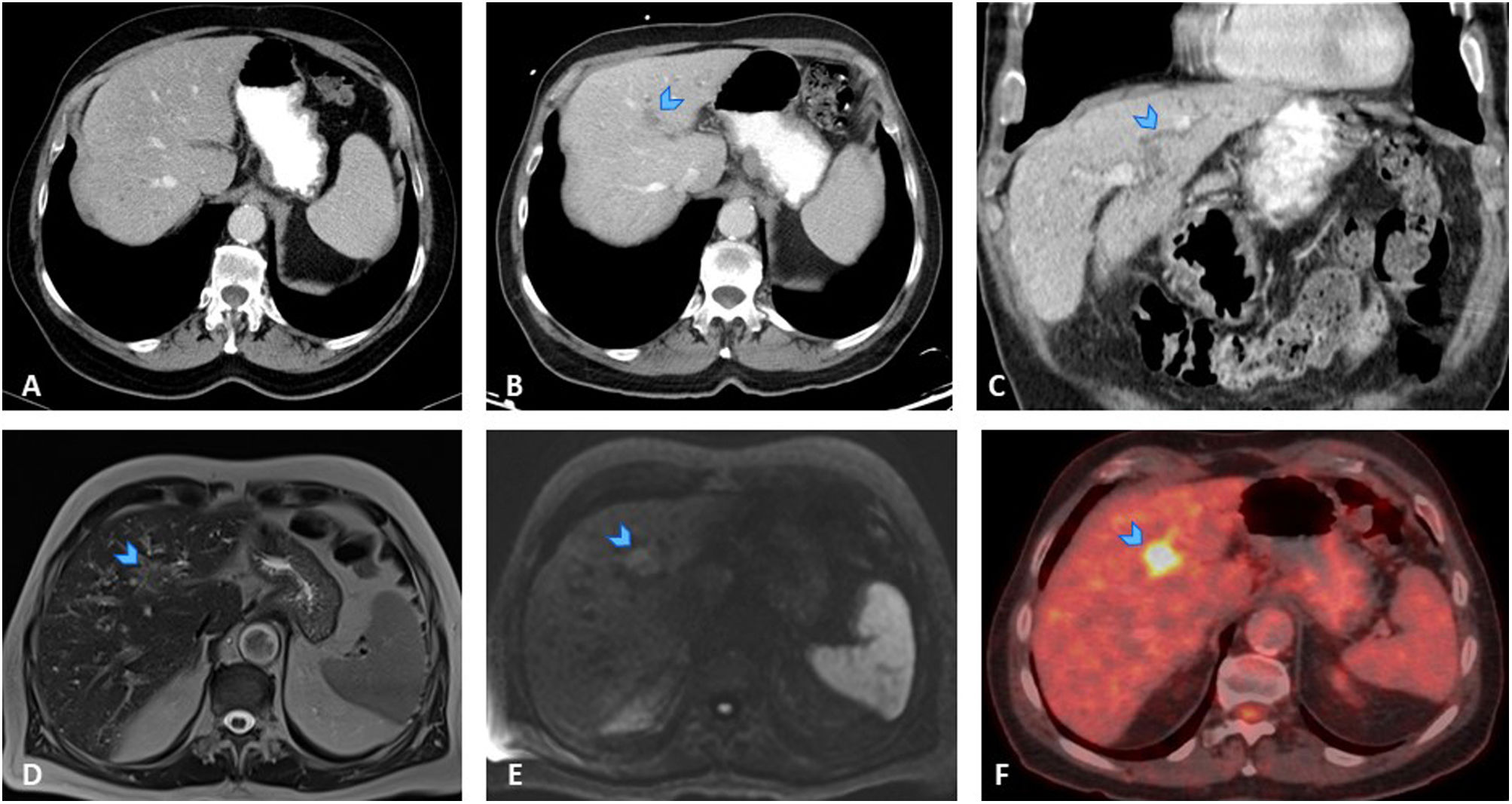

A 76-year-old man with history of colon cancer in 2013, treated with surgery and chemotherapy, and disease-free since. (A) Axial CT slice of the abdomen in follow-up scan showing small liver cysts with no signs of distant spread. (B, C) Follow-up CT slices showing faint, ill-defined hypodense focal area in segment II (B, arrowhead), along with mild dilation of some intrahepatic bile ducts distal to lesion (C, arrowhead). (D) Slice from T2-weighted sequence of MRI staging scan showing ill-defined lesion as mildly hyperintense on T2 (arrowhead). (E) Slice from diffusion-weighted sequence of MRI staging scan revealing lesion as mildly hyperintense on high b-value sequences (arrowhead). Findings suspicious for malignancy. Given the 10-year interval since the primary tumour and biliary dilation, the differential diagnosis included liver metastasis (less likely) and primary cholangiocarcinoma. F) Axial PET-CT slice showing marked hypermetabolism in suspicious lesion (arrowhead). As this was a solitary lesion with aggressive features, a left hepatectomy was performed without prior biopsy of the lesion. The histological result of the surgical specimen was a neoplasm with intrabiliary growth consistent with cholangiocarcinoma.

Chemotherapy frequently induces hepatic side effects that may manifest radiologically as focal liver lesions.11,12

Nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH) and focal nodular hyperplasia-like (FNH-like) lesions consist of benign regenerative nodules caused by alterations in hepatic blood flow, leading to sinusoidal obstruction syndrome and subsequent hepatocyte hyperplasia.13,14

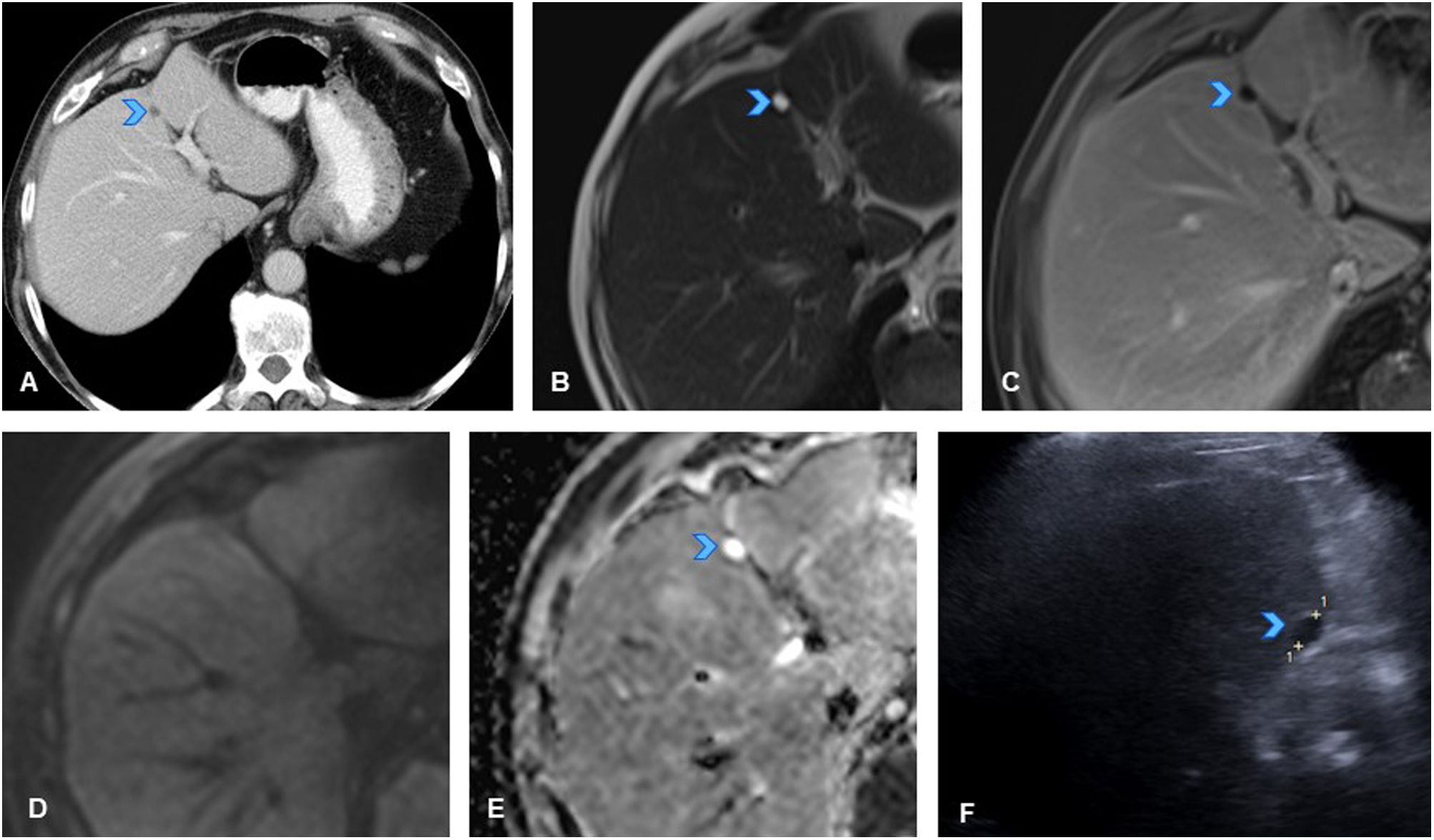

On CT/MRI, these lesions appear as hypervascular nodules, with or without a central scar. Thus, when a hypervascular liver lesion arises in patients whose primary tumours typically produce hypovascular metastases, it is essential to consider if the patient has undergone platinum-based chemotherapy (commonly used for colon cancer, in which metastases are usually hypovascular). If such treatment has been administered, NRH/FNH-like lesions should be the primary diagnostic consideration.15 The definitive diagnosis is obtained with hepatocyte-specific contrast enhanced MRI of the liver. With this modality, NRH/FNH-like lesions demonstrate contrast uptake in the hepatocellular phase as they consist of viable hyperplastic hepatocytes and while they have an altered biliary drainage system, they retain their biliary excretion capacity13,15,16 (Fig. 4). In contrast, metastases remain hypovascular due to the absence of viable hepatocytes.

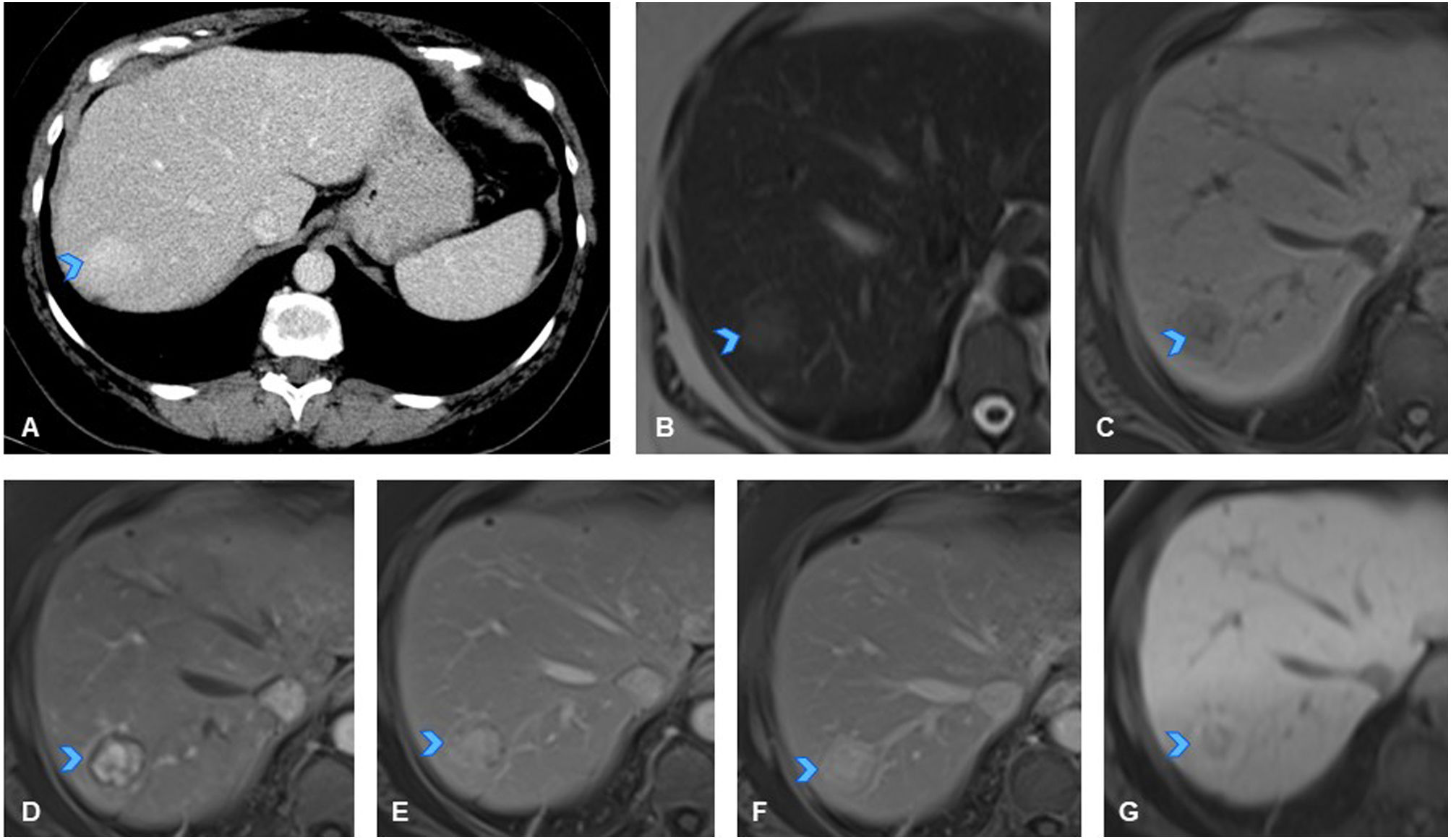

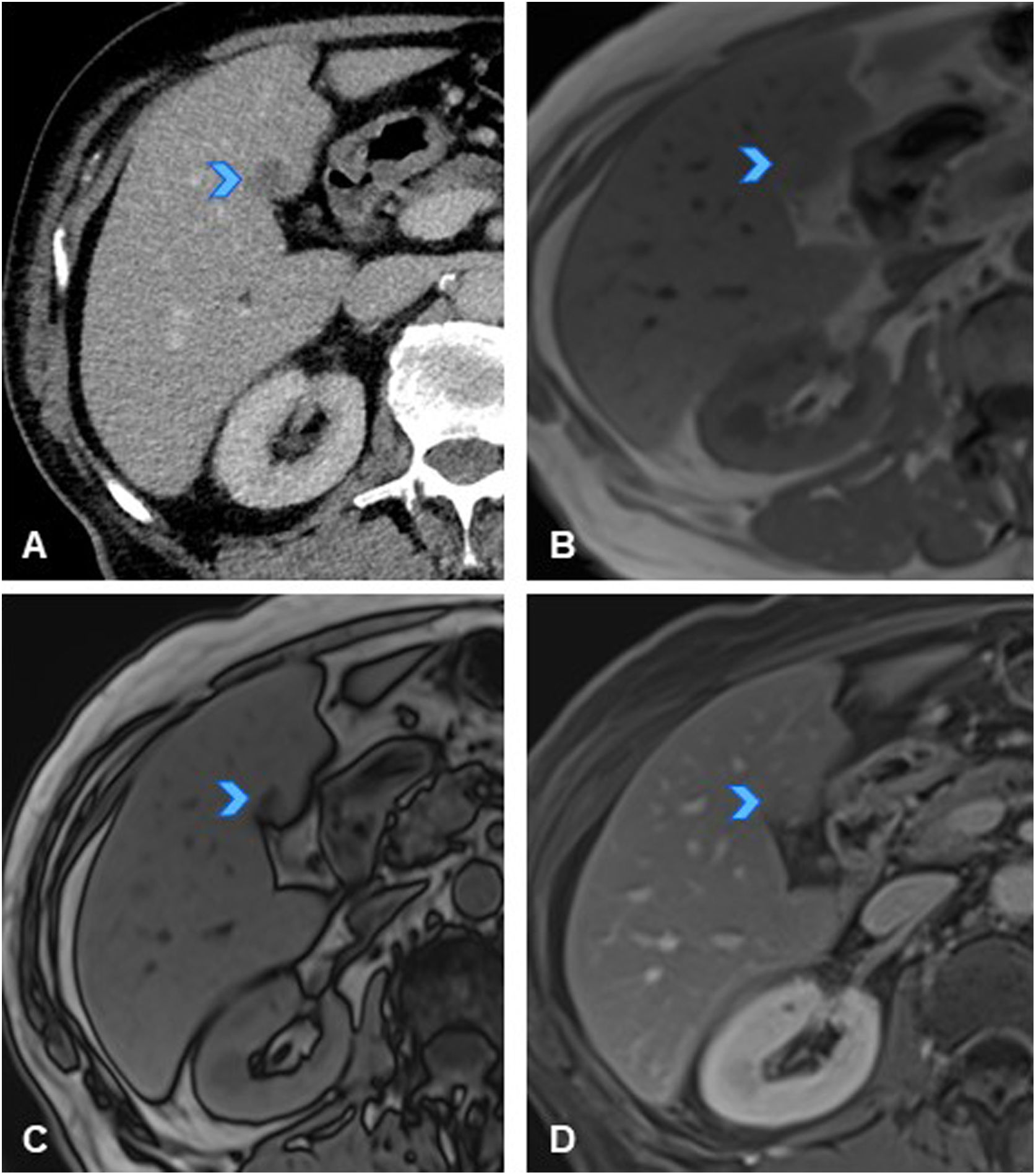

A 50-year-old woman with history of sigmoid colon cancer (T3N1M0), treated with folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX), resulted in patient being disease-free. (A) Axial CT slice of the abdomen in follow-up scan six years after treatment, showing new-onset hyperdense liver lesion in segment VII (arrowhead). (B) Axial slice of T2-weighted sequence of liver MRI showing a mildly hyperintense nodular lesion on T2 (arrowhead). (C) Axial slice of T1-weighted sequence of liver MRI showing lesion as slightly hypointense with even more hypointense central area (arrowhead). (D, E, F) Axial slices from dynamic MRI study of the liver showing hypervascular lesion in arterial phase (D, arrowhead) with mild persistent hyperenhancement in later phases (E, F, arrowheads). Given these findings are not typical of liver metastases from colon cancer (which are usually hypovascular), and considering history of oxaliplatin treatment, study was completed with MRI using hepatocyte-specific paramagnetic contrast with mixed (biliary and renal) excretion before recommending liver biopsy. (G) Dynamic study slice with hepatocyte-specific contrast in hepatocellular phase showing peripheral contrast uptake (arrowhead), confirming hepatocellular nature of lesion, with a centrally hypoenhancing area (scar). In this clinical context, the lesion was consistent with nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH)/focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH)-like lesion, making biopsy unnecessary.

Note: A hypervascular lesion in an oncology patient treated with platinum-based chemotherapy is suggestive of an NRH/FNH-like lesion. A hepatocyte-specific contrast enhanced MRI of the liver will confirm the diagnosis, thus avoiding biopsy.

Hepatocellular adenomasHepatocellular adenomas are benign lesions that typically occur in women of childbearing age who take oral contraceptives or in patients undergoing steroid treatment.17,18

There are four types of adenomas, of which the inflammatory subtype is the most common, accounting for 30–50% of cases. Histologically, these lesions consist of hepatocytes with abundant lipid and glycogen content, leading to inflammatory ductal changes.18 They may develop complications such as haemorrhage or malignant transformation into hepatocellular carcinoma.17–19 Imaging findings that help differentiate adenomas from metastases include the presence of fat (Fig. 5), and contrast enhancement patterns. Adenomas are usually hypervascular in the arterial phase and either iso- or hypovascular in the portal or delayed phase.18 Additionally, in the hepatocellular phase, they generally remain hypovascular, which helps distinguish them from NRH/FNH-like lesions. The definitive diagnosis is histological.16,18

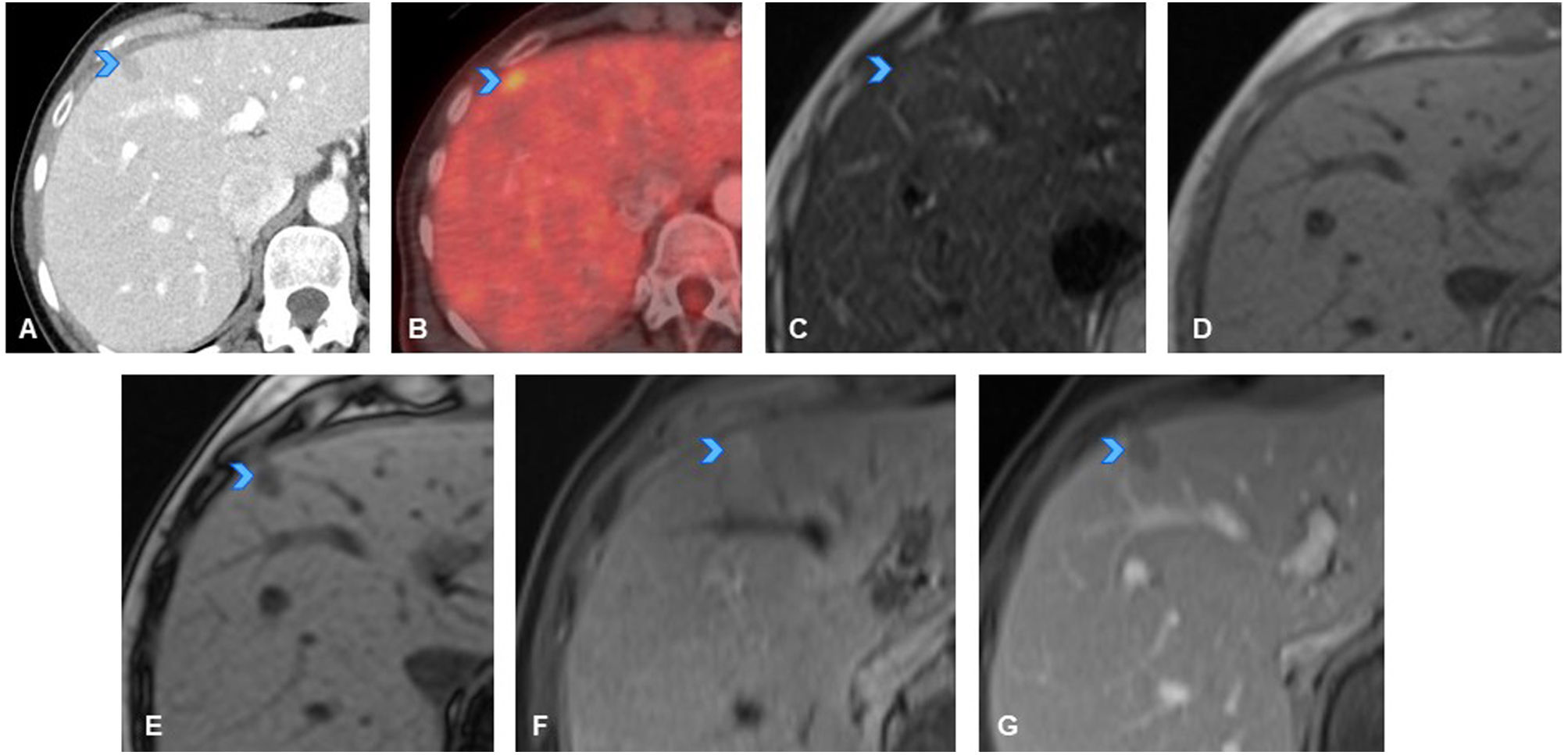

A 38-year-old woman diagnosed with breast cancer in 2010, treated with lumpectomy, lymphadenectomy, radiotherapy, and tamoxifen. She developed breast cancer again in 2018 (pT1cpNx), surgically treated. (A) Axial slice from follow-up CT scan showing new-onset hypodense liver lesion in segment VII-IV, suspicious for metastasis (arrowhead). (B) Axial PET-CT slice showing hypermetabolism in the liver lesion (arrowhead), confirming metastatic disease. Patient began chemotherapy and was later evaluated by multidisciplinary team for potential metastasectomy. Therefore, liver MRI was performed before surgery. (C–G) Axial slices from liver MRI showing mildly hyperintense lesion on T2 (C, arrowhead), isointense on in-phase T1 (D), and signal loss on opposed-phase T1 (E, arrowhead), indicating fat content, which strongly suggests a diagnosis other than liver metastasis. Dynamic study shows mild hyperenhancement in the arterial phase (F, arrowhead) with washout in the portal phase (G, arrowhead), findings that in a patient with no chronic liver disease, are highly suggestive of liver adenoma. Upon further questioning, the patient reported oral contraceptive use. Adenoma diagnosis confirmed by percutaneous biopsy.

Note: The presence of fat in metastases is very rare and should prompt consideration of alternative diagnoses.

Cysts and haemangiomasThese lesions are often diagnosed during the initial oncological staging, so do not typically cause diagnostic uncertainty in subsequent CT follow-ups. However, it is important to consider that cysts can change over time—they may grow, shrink, appear, or disappear.20 Haemangiomas may go unnoticed in some studies due to differences in phase acquisition, so in some follow-up studies, they may be mistaken for new-onset lesions. In such cases, a careful review of previous imaging studies is essential to determine whether the lesion was present in prior scans. If so, and the lesion has not grown, it is most likely benign. If there is uncertainty, MRI is usually sufficient to establish a definitive diagnosis without requiring a biopsy. Both cysts and haemangiomas appear markedly hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging, unlike metastases (except for mucinous tumours or those with extensive necrosis).2 Furthermore, they typically do not show diffusion restriction. In terms of contrast enhancement, cysts do not enhance (Fig. 6) while haemangiomas—which typically exhibit progressive centripetal nodular enhancement—sometimes show a rapid filling pattern, particularly in small lesions. They appear hyperenhanced in the arterial phase and isoenhanced in the other phases, which can make differentiation from hypervascular metastases very challenging. In such cases, T2-weighted sequences and diffusion imaging should be used to aid differentiation.13,16

A 78-year-old man with history of rectal cancer (T3N0M0). (A) Axial slice from follow-up CT scan showing new-onset hypodense focal liver lesion in segment IV (arrowhead). (B) Axial slice from T2-weighted sequence of liver MRI showing markedly hyperintense appearance of lesion (arrowhead), hypointense on T1 (not shown). (C) Axial slice from dynamic MRI study showing persistent hypovascularity of lesion (arrowhead). (D, E) Axial slices from diffusion-weighted sequences and ADC maps respectively, revealing no diffusion restriction, appearing isointense on high b-value sequences (D) and hyperintense on ADC maps (E, arrowhead). Given that there are exceptional cases of cystic-appearing metastases, early ultrasound follow-up was recommended to monitor progression. (F) Axial slice of abdominal ultrasound performed two months later confirmed its cystic nature and lesion stability (arrowhead).

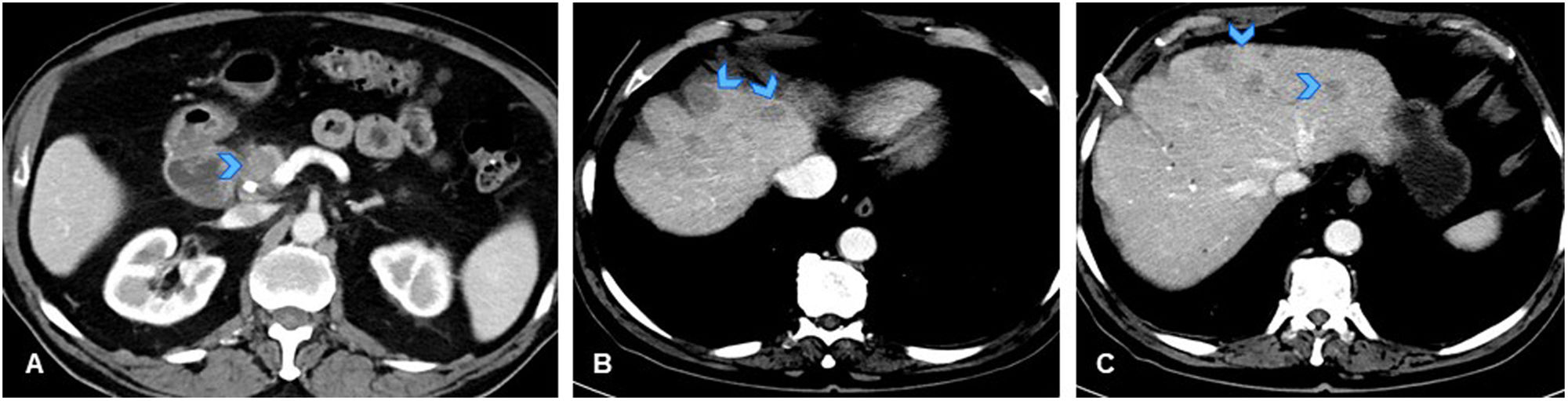

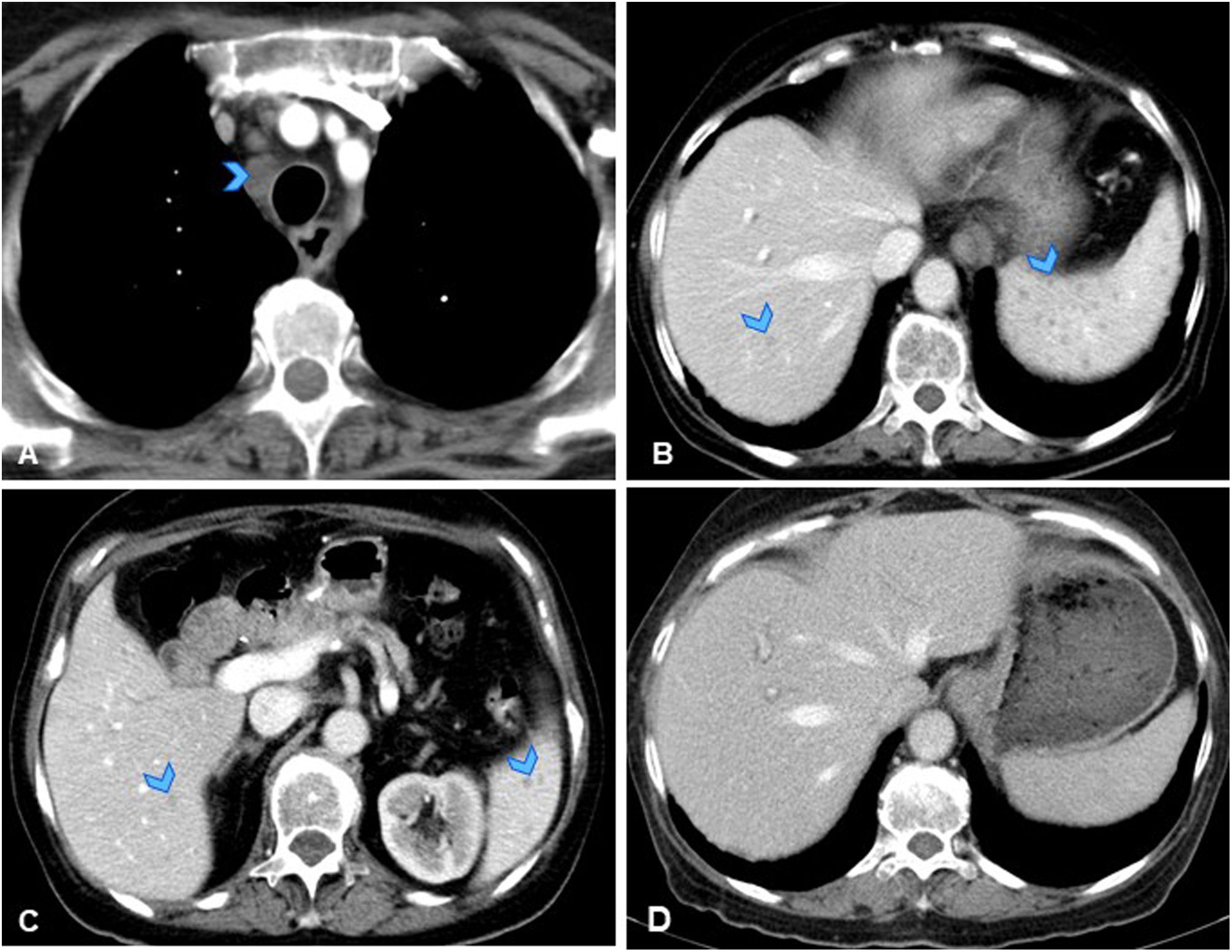

Granulomatous hepatitis is a chronic inflammatory liver condition characterised by granuloma formation. The most common causes are granulomatous diseases, such as sarcoidosis or tuberculosis, although the exact aetiology may be unknown.21 These granulomas can aggregate, forming radiologically visible pseudotumoral lesions that may exhibit miliary, nodular, or multinodular patterns.22 These lesions are typically hypovascular, making them indistinguishable from metastases. Additionally, MRI does not provide any specific characteristics to differentiate them.21,23

As a result, distinguishing granulomatous hepatitis from metastases can be nearly impossible on imaging, potentially leading to significant diagnostic errors that affect patient management and prognosis (Fig. 7). In these cases, we should take note of clinical signs of infection and atypical radiological findings, such as splenomegaly or necrotic lymphadenopathy (Fig. 8). In cases of clinical suspicion, screening for inflammatory or infectious diseases may be recommended, along with early follow-up imaging after initiating appropriate treatment to assess lesion progression. If no alternative diagnosis is established and the suspicion of metastases remains low, a percutaneous biopsy is indicated.23,24

(A) Axial slice from CT of the abdomen for 79-year-old male patient with diagnosis of tumour in the pancreatic head (arrowhead), with no distant metastases, initially considered resectable. (B, C) Axial slices from follow-up CT scan performed before surgery, showing appearance of multiple hypodense liver lesions indicative of metastases (arrowheads). Findings mean patient is no longer considered a surgical candidate. As no tumour sample had yet been obtained, a percutaneous biopsy was performed on one of the liver lesions, followed by referral to oncology. Ultrasound-guided biopsy of liver lesion revealed pathological findings of acute hepatitis with granulomatous inflammation foci and no malignant cells. Biopsy of the pancreatic lesion confirmed adenocarcinoma. Since no liver metastases were identified, surgical treatment was performed on the pancreatic tumour, with resection of several liver nodules that were found to be necrotising granulomas, with no evidence of microorganisms or malignant cells. Negative PCR for mycobacteria. Pathology report concluded that the granulomas could correspond to a foreign body reaction related to prior surgical manipulation.

A 73-year-old immunocompromised woman (on corticosteroids and chemotherapy) with history of pancreatic adenocarcinoma (T1N1M0), later disease-free. (A, B, C) Axial slices from follow-up CT showing new-onset hypodense mediastinal lymphadenopathy (A, arrowhead), numerous punctiform hypodense splenic lesions, and very faint hypodense focal liver lesions (B, C, arrowheads). These findings not present on urgent CT scan performed one month earlier due to abdominal pain and diarrhoea. Given recent onset, atypical behaviour of the lesions and immunocompromised status of patient, an opportunistic infection was considered the primary diagnostic possibility, although metastatic spread could not be ruled out. Upon further questioning, the patient reported two months of low-grade evening fever and occasional chills. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Fine-needle aspiration of mediastinal lymph node was performed, showing necrosis, and positive PCR for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, confirming diagnosis of miliary tuberculosis with hepatosplenic and lymphatic involvement. (D) Axial CT slice from follow-up scan performed four months after specific tuberculosis treatment, showing resolution of lesions.

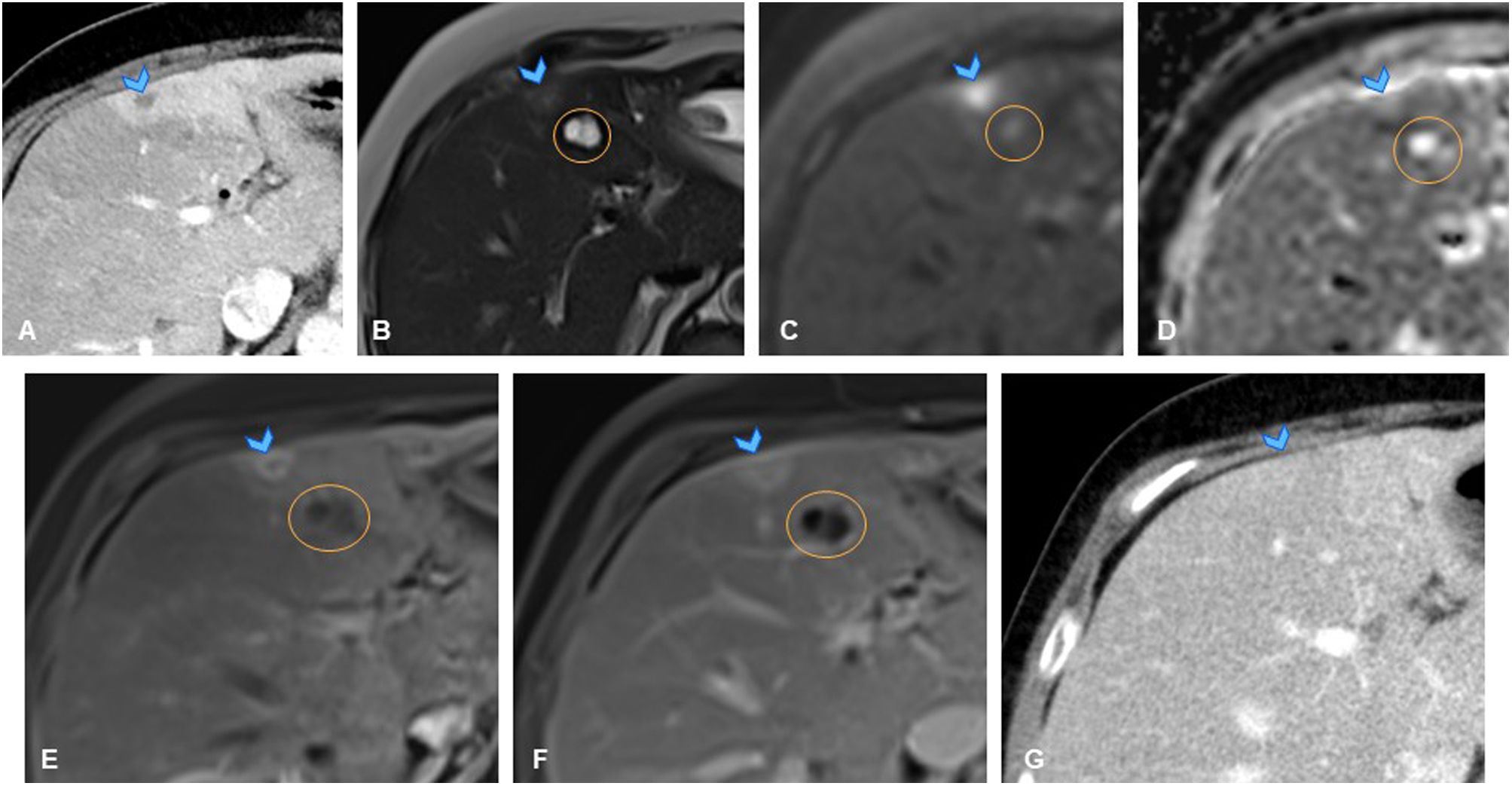

Liver abscesses are collections of pus resulting from bacterial, fungal, or parasitic infections.25 They appear as hypovascular nodular lesions with peripheral enhancement. The presence of gas, air-fluid levels or internal septations is suggestive of a liver abscess.25 A less common but characteristic finding is the ‘double target’ sign, which consists of a central hypodense area with an inner hyperdense peripheral ring in the arterial phase that persists in the delayed phases (corresponding to the pyogenic membrane), and an outer hypodense peripheral ring in the arterial phase that becomes hyperdense in the delayed phases (associated with perilesional inflammatory changes).23,24 On MRI, liver abscesses exhibit low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and variable hyperintensity on T2-weighted images. They may also present with perilesional oedema, which helps distinguish them from metastases.24

However, imaging findings are not specific, and the appearance of liver abscesses and liver metastases frequently overlap, making differentiation challenging. Once again, correlation with clinical findings and lesion evolution over time is essential. The appearance of multiple lesions over a short period (days or a few weeks) in a patient with symptoms of infection is more indicative of an infectious rather than metastatic process (Fig. 9).

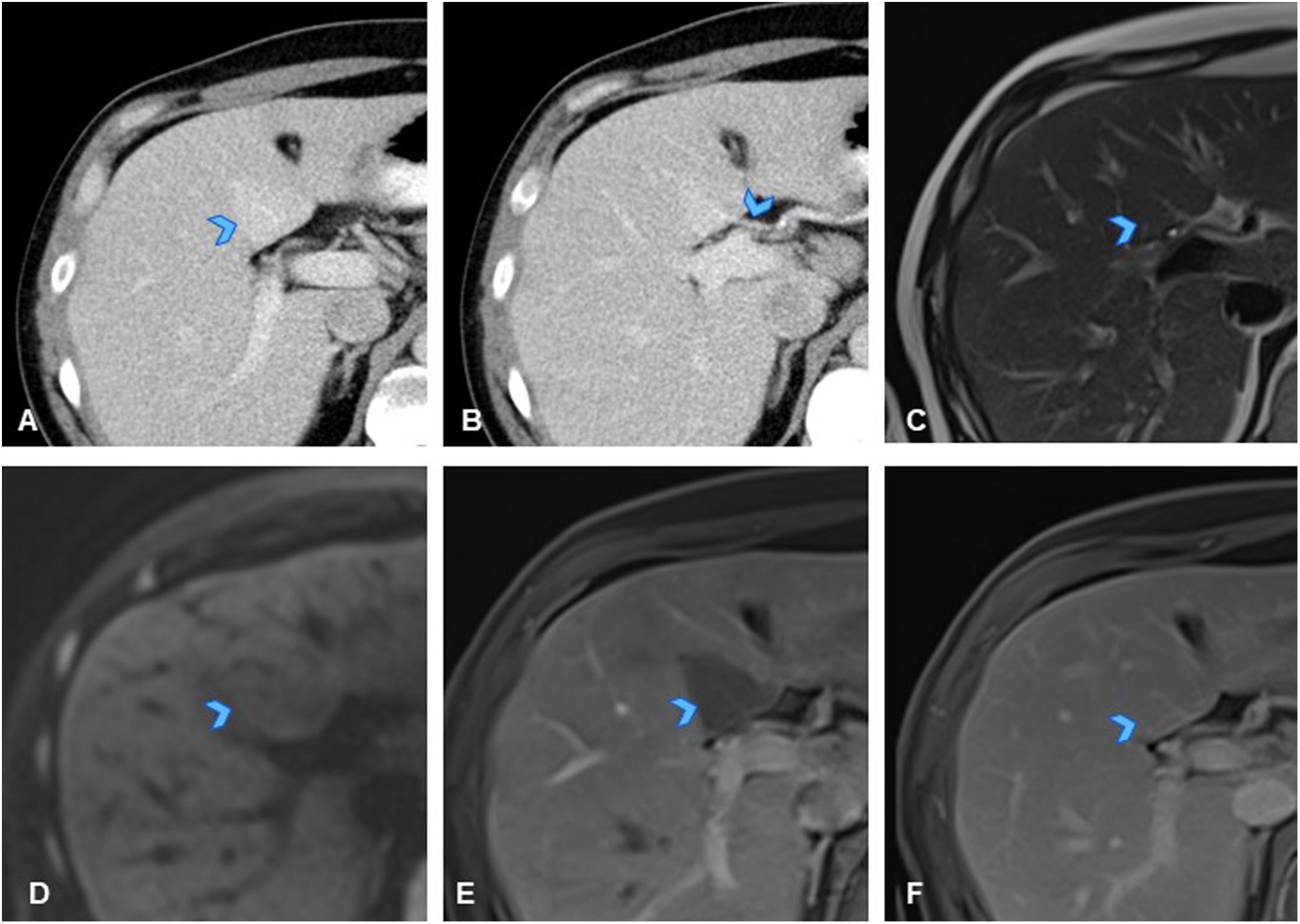

A 68-year-old woman with history of duodenal cancer (T2N0M0) treated surgically with cephalic duodenopancreatectomy, leaving her disease-free, attended the emergency department with fever and liver function abnormalities. (A) Axial slice of CT of the abdomen, identifying two new-onset hypodense liver lesions: one in segment VII (not shown) and another in segment IVa-b (arrowhead), with marked hypervascularisation in peripheral parenchyma. While these findings do not rule out metastases in the current clinical context, they could correspond to liver abscesses. (B) Axial slice from T2-weighted sequence of liver MRI showing the segment IVa-b lesion as mildly hyperintense, with even more hyperintense centre (arrowhead), adjacent to cyst (orange circle in B–F). Lesion appeared hypointense on T1 (not shown). (C, D) Axial slices from diffusion-weighted sequences of liver MRI showing no diffusion restriction in lesion (arrowheads). (E, F) Axial slices from dynamic liver MRI study, demonstrating ring-shaped arterial enhancement of lesion (E, arrowhead), which progressively increases in later phases (F, arrowhead). In the clinical context, and given absence of diffusion restriction, an abscess was considered the primary diagnosis, and antibiotic treatment was initiated. (G) Axial slice from early follow-up CT of the abdomen one month later, showing resolution of the lesions (arrowhead), confirming diagnosis of abscesses.

Note: Inflammatory and infectious liver lesions are often indistinguishable from metastases on imaging. Their rapid onset, the presence of perilesional oedema, and clinical signs of infection should raise suspicion of an infectious or inflammatory process.

PseudolesionsFocal steatosisFocal steatosis is the accumulation of fat vacuoles within hepatocytes and can appear in different ways on imaging, whether diffuse, focal, or multifocal.26 When it first appears, it may resemble a true lesion.26 For diagnostic purposes, it is useful to note that involvement most commonly affects the posterior aspect of segment IV, the falciform ligament, the periportal region, and the gallbladder fossa.27

On ultrasound, focal steatoses appear as focal hyperechoic areas, while on CT, hypodense images have linear margins in both non-contrast and contrast-enhanced studies. They do not exert a mass effect on adjacent structures or distort regional vessels.26 MRI provides the definitive diagnosis by revealing fat, which appears as a signal drop (hypointensity) on T1-weighted opposed-phase sequences. In dynamic MRI studies, focal steatosis presents in a similar or slightly hypoenhanced way compared to the liver parenchyma26 (Fig. 10).

A 67-year-old man with history of lung adenocarcinoma (T3N0M0) undergoing immunotherapy, previously treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgery. (A) Axial slice from follow-up CT showing new-onset hypodense subcapsular liver lesion in segment IVb (arrowhead). Study completed with liver MRI, showing minimally hyperintense nodular lesion on T2 with no diffusion restriction (not shown). (B, C) Axial slice from T1-weighted sequence of liver MRI showing lesion as isointense on in-phase imaging (B, arrowhead) with signal loss on opposed-phase imaging (C, arrowhead), confirming presence of fat and ruling out metastasis. (D) Axial slice from dynamic liver MRI showing no contrast uptake in the lesion, which appears mildly hypointense in delayed phase (D, arrowhead), consistent with focal steatosis.

The opposite is seen in areas of fat preservation, which are typically observed in patients with diffuse steatosis, where focal areas of fat preservation may appear with the same distribution as the previously described focal steatosis areas.28

Perfusion disordersThe liver has a dual blood supply, receiving 70% from the portal vein and 30% from the hepatic artery, with compensatory mechanisms between them. Occasionally, a third venous supply may exist, either from aberrant veins or segments of normal veins entering the liver parenchyma independently of the portal system.29,30

Perfusion disorders result from an imbalance between arterial and venous supply due to anatomical variations, shunts, trauma, or other factors.30 On CT and MRI, these disorders typically appear as nodular or triangular areas with no mass effect, showing altered contrast uptake, usually hyperenhancement. A characteristic feature of these lesions is that they are only visible in one phase of the dynamic MRI study, most commonly the arterial phase, although this is not always the case. They become homogeneous in later phases and do not appear on morphological sequences or diffusion-weighted imaging29 (Fig. 11).

A 40-year-old man with history of caecal cancer (T3N0M0) treated with surgery and chemotherapy, resulting in being disease-free. (A) Axial slice from follow-up CT showing faint hyperdense nodular liver lesion in segment IV (arrowhead). (B) Axial CT slice demonstrating that lesion does not exert mass effect, and within it, there is a vascular structure with extrahepatic origin (aberrant right gastric vein) (arrowhead), raising significant suspicion of pseudolesion due to perfusion disorder related to an anomalous vessel. (C) Axial slice from T2-weighted sequence of liver MRI, where the lesion is identified as isointense on T2 (arrowhead), and iso/mildly hypointense on T1 (not shown). (D) Axial slice from diffusion sequence of MRI, in which lesion is not seen to restrict diffusion (arrowhead). (E, F) Axial slices from dynamic liver MRI showing less enhancement in early portal phase than liver parenchyma because blood supply occurs through aberrant extrahepatic vessel and not through the portal circulation (E, arrowhead), and homogeneous, isointense enhancement compared to liver parenchyma in later phases (F, arrowhead), confirming diagnosis of pseudolesion due to a perfusion disorder. Lesions characterised by only appearing on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI and not in morphological or diffusion sequences.

Note: Focal liver images with no mass effect that respect vascular structures may be pseudolesions.

ConclusionsThe detection of a new-onset focal liver lesion in an oncology patient presents a diagnostic challenge. While metastases should be the primary diagnostic consideration, atypical radiological behaviour or the presence of infectious symptoms should prompt consideration of alternative diagnoses. Radiological findings, combined with a comprehensive patient assessment, are essential for accurate diagnosis and can help avoid unnecessary changes to oncological management.

CRediT authorship contribution statement- 1

Research coordinators: HPA, CCR.

- 2

Development of study concept: HPA, CCR.

- 3

Gathering of case studies: CCR.

- 4

Literature search: HPA, CCR.

- 5

Drafting of article: HPA, CCR.

- 6

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: HPA, CCR, FBB, AFU, FNT, MJPdR.