80% of renal carcinomas (RC) are diagnosed incidentally by imaging. 2–4% of "sporadic" multifocality and 5–8% of hereditary syndromes are accepted, probably with underestimation. Multifocality, young age, familiar history, syndromic data, and certain histologies lead to suspicion of hereditary syndrome. Each tumor must be studied individually, with a multidisciplinary evaluation of the patient. Nephron-sparing therapeutic strategies and a radioprotective diagnostic approach are recommended.

Relevant data for the radiologist in major RC hereditary syndromes are presented: von-Hippel-Lindau, Chromosome-3 translocation, BRCA-associated protein-1 mutation, RC associated with succinate dehydrogenase deficiency, PTEN, hereditary papillary RC, Papillary thyroid cancer- Papillary RC, Hereditary leiomyomatosis and RC, Birt-Hogg-Dubé, Tuberous sclerosis complex, Lynch, Xp11.2 translocation/TFE3 fusion, Sickle cell trait, DICER1 mutation, Hereditary hyperparathyroidism and jaw tumor, as well as the main syndromes of Wilms tumor predisposition.

The concept of "non-hereditary" familial RC and other malignant and benign entities that can present as multiple renal lesions are discussed.

El 80% de los carcinomas renales (CR) se diagnostican incidentalmente por imagen. Se aceptan 2–4% de multifocalidad “esporádica” y 5–8% de síndromes hereditarios, probablemente con infraestimación. Multifocalidad, edad joven, historia familiar, datos sindrómicos y ciertas histologías hacen sospechar síndrome hereditario. Debe estudiarse individualmente cada tumor y multidisciplinarmente el paciente, con estrategias terapéuticas conservadoras de nefronas y abordaje diagnóstico radioprotector.

Se revisan los datos relevantes para el radiólogo en los síndromes de von Hippel-Lindau, Translocación de cromosoma-3, Mutación de proteína-1 asociada a BRCA, CR asociado a déficit en Succinato-deshidrogenasa, PTEN, CR papilar hereditario, Cáncer papilar tiroideo-CR papilar, Leiomiomatosis hereditaria y CR, Birt-Hogg-Dubé, Complejo esclerosis tuberosa, Lynch, Translocación Xp11.2/Fusión TFE3, Rasgo de células falciformes, Mutación DICER1, Hiperparatoridismo y tumor mandibular hereditario, así como los principales síndromes de predisposición a tumor de Wilms.

Se discuten el CR familiar “no hereditario” y otras entidades malignas y benignas que pueden presentarse como lesiones renales múltiples.

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the sixth most common neoplasm (3% of all cancer cases in adults). Its incidence is on the rise, with more than 80% of diagnoses now resulting from incidental findings during imaging studies. Clear cell RCC (ccRCC) constitutes two thirds of all RCCs, followed in order of frequency by papillary RCC (pRCC) and chromophobe RCC (cRCC).

It should be noted that the aim of this paper is not to provide a general description of the radiological characteristics of renal tumours. Renal tumours are common incidental findings on B-mode ultrasound. Although angiomyolipomas (AMLs) are typically hyperechogenic, and necrosis is commonly found in conjunction with cRCCs, specific findings for cRCCs are not described. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound that uses contrast agents containing microbubbles has proved highly useful in the characterisation of cystic lesions and in the real-time definition of solid tumours (particularly useful for demonstrating vascularisation in pCCRs); however, its potential has not been sufficiently shown for tumour characterisation. Instead, multiphasic CT is more commonly used for this purpose. In general, cRCCs tend to enhance more intensely, earlier, and more heterogeneously, while pRCCs enhance more discreetly. Scarring might be seen in cases of oncocytomas and cRCCs, occasionally confused with the foci of necrosis seen in cRCCs. A gross presence of fat is characteristic of AMLs, but this can also be seen in cRCCs and other subtypes. The quantification of iodine following spectral acquisition offers promising data for characterisation. Multiparametric MRI provides important differential information (Appendix B. Fig. S1 of the supplementary material). However, various overlaps mean that it is rarely possible to make an individual diagnosis with confidence. Various radiomics models, such as CT texture analysis or CT- or MRI-based artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms have proved useful in the characterisation of tumour type and grade, and they may even have potential treatment implications when combined with with embryonic research on genomic correlation (radiogenomics). The following are some promising tools from nuclear medicine: 99mTc-sestamibi SPECT/CT for the diagnosis of oncocytomas or hybrid oncocytic/cRRC tumours, 124I- or 89Zr-girentuximab PET/CT for the diagnosis of cRCC, and 11C-acetate PET/CT in combination with 18F-FDG PET/CT for differentiation between AMLs and cRCCs.1,2

Multifocality is reported in between two and four percent of cases in radiological series, while it is detected in up to 25% of cases in histological series.3–5 Malignancy is bilateral in 90% of cases.4–6

It is widely accepted that between five and eight percent of RCCs are hereditary; however, some studies estimate that a hereditary component is present in up to 58% of cases.5,7–9 With only a few exceptions, the radiological behaviour of tumours associated with a hereditary syndrome is indistinguishable from that of sporadic tumours.

Important: Upon detection of multiple renal tumours, each individual tumour must be evaluated and a percutaneous biopsy should be considered. A multidisciplinary approach should be applied, which should include urologists, nephrologists and oncologists as a minimum, and often geneticists too.

This paper describes renal tumours and other renal mimickers with potential for multifocal and/or bilateral involvement. We discuss the main hereditary renal tumour syndromes and the role of the radiologist in the management of these patients.

Sporadic multifocal renal tumoursWhenever multifocal renal tumours are present, hereditary syndromes should be considered.

The tumours are either all benign or all malignant in 49–95% of cases, with the concordance histologically confirmed in 57–93%5 (Fig. 1), and this level is lower in more recent series. Multifocal sporadic tumours are most common in pRCC (10.9%), followed by cRCC (2%) and cRCC (1.9%).3,4,10

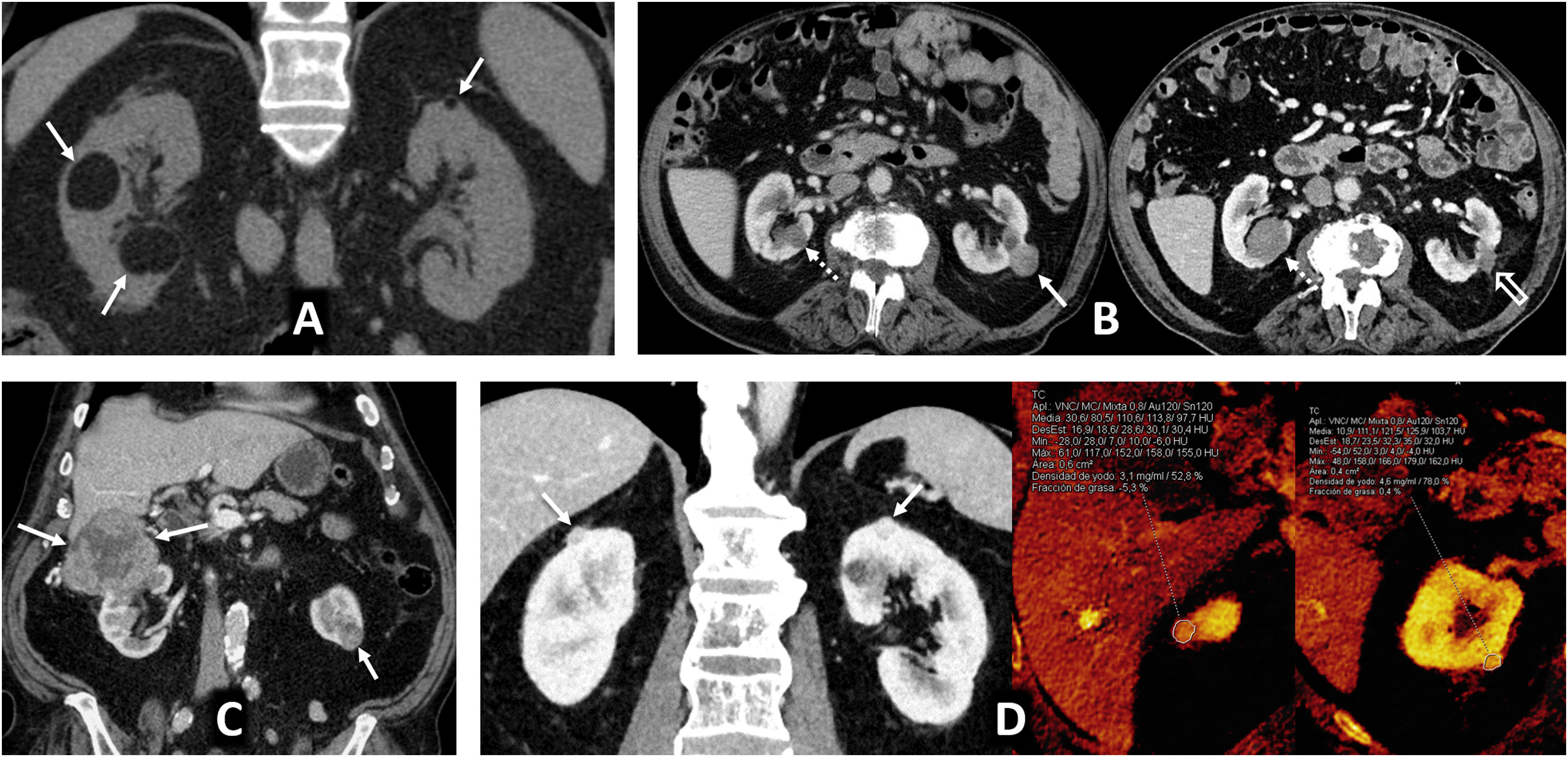

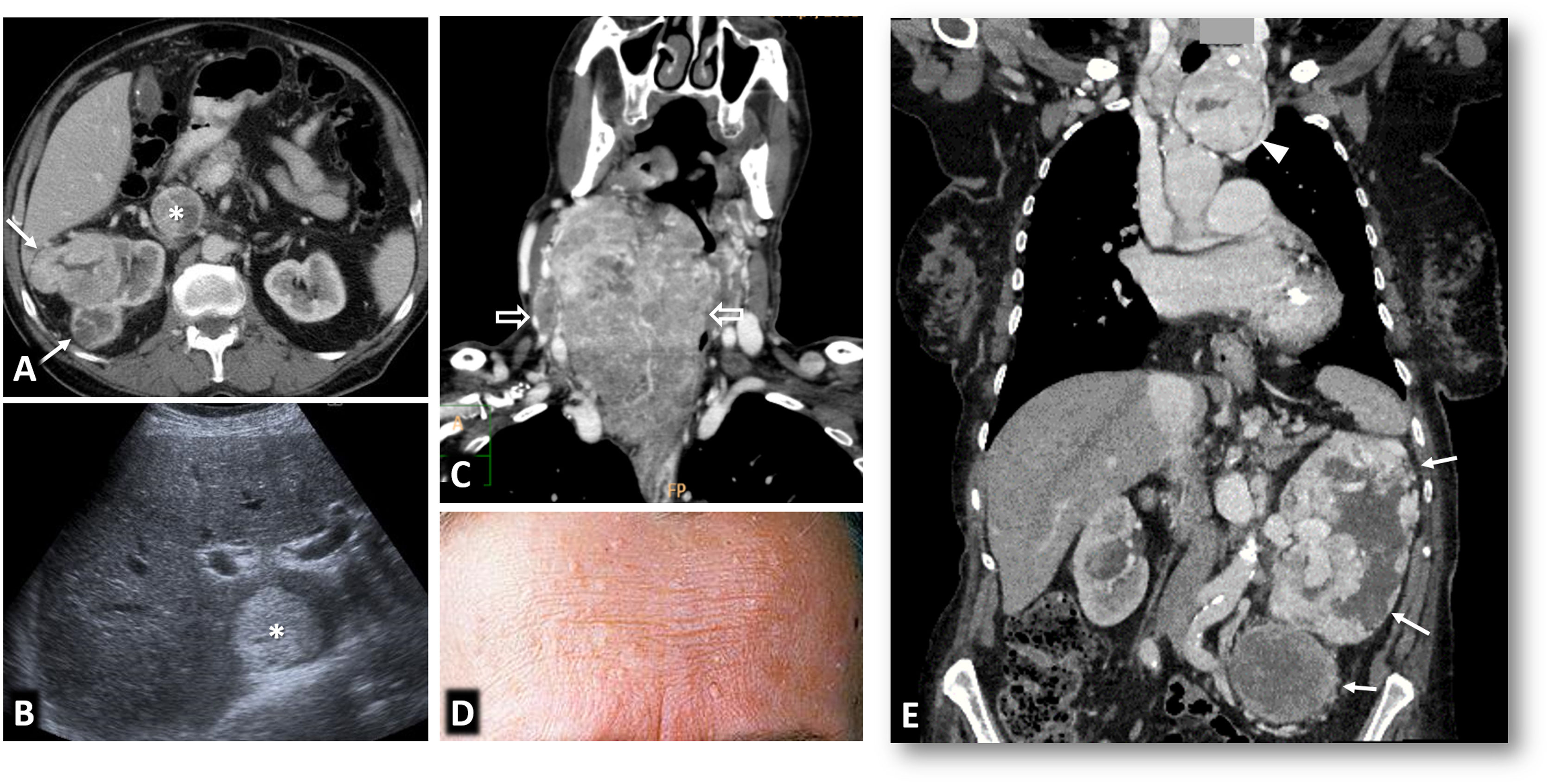

Multiple sporadic bilateral renal tumours that are histologically concordant. (A) Bilateral lipomas or angiomyolipomas with an almost exclusively fatty component (arrows) were found incidentally on non-contrast CT in a 65-year-old man with no other clinical or radiological features suggestive of tuberous sclerosis. (B) Bilateral papillary renal cell carcinoma (pRCC). A 78-year-old male, under follow-up for a mildly hyperattenuating left renal tumour found incidentally in a non-contrast study with low enhancement (study not shown). In the follow-up examination (left; axial composite image) moderate growth is observed (arrow), with another contralateral lesion (dashed arrow) going unnoticed. A partial left nephrectomy was performed. Image from another follow-up examination two years later (right) shows the area that underwent the partial nephrectomy (hollow arrow) and the contralateral lesion which has grown (dashed arrow). An ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy was performed. The histological result in both cases was pRCC, which was then classified as type 1. The patient opted for active surveillance, and slight growth of the right lesion was observed in the only follow-up examination, performed one year later (not shown). (B) Bilateral clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). A 67-year-old male with haematuria. CT scan in the nephrographic phase shows an upper right renal lesion (arrows) with intense enhancement peaking in the corticomedullary phase (not shown) and central areas of necrosis, corresponding to a ccRCC pT3 pN1 after nephrectomy, and a smaller lower left lesion (arrow) with intense and slightly heterogeneous enhancement. This lesion was removed and histologically confirmed as pT1a. No germline mutation for Von Hippel-Lindau was detected and there were no other tumours in the right nephrectomy specimen. (D) Bilateral oncocytic neoplasms in a 75-year-old male. Incidental finding of two small upper lesions with moderate enhancement on average coronal image of spectral acquisition in nephrographic phase (arrows), with iodine density of 3.1 mg/mL on the iodine map of the same study in the right lesion, 4.6 in another ipsilateral lesion, and 3.2 in the left lesion (not shown). A core needle biopsy was performed on the right lesion, which resulted in an oncocytic diagnosis. The same histology was assumed for the rest of the lesions which behaved similarly. The result from the single-gene test for Birt-Hogg-Dubbé was negative. The patient opted for active surveillance.

Multiple forms of coexistence of histologically different tumours have been described 11 (Fig. 2).

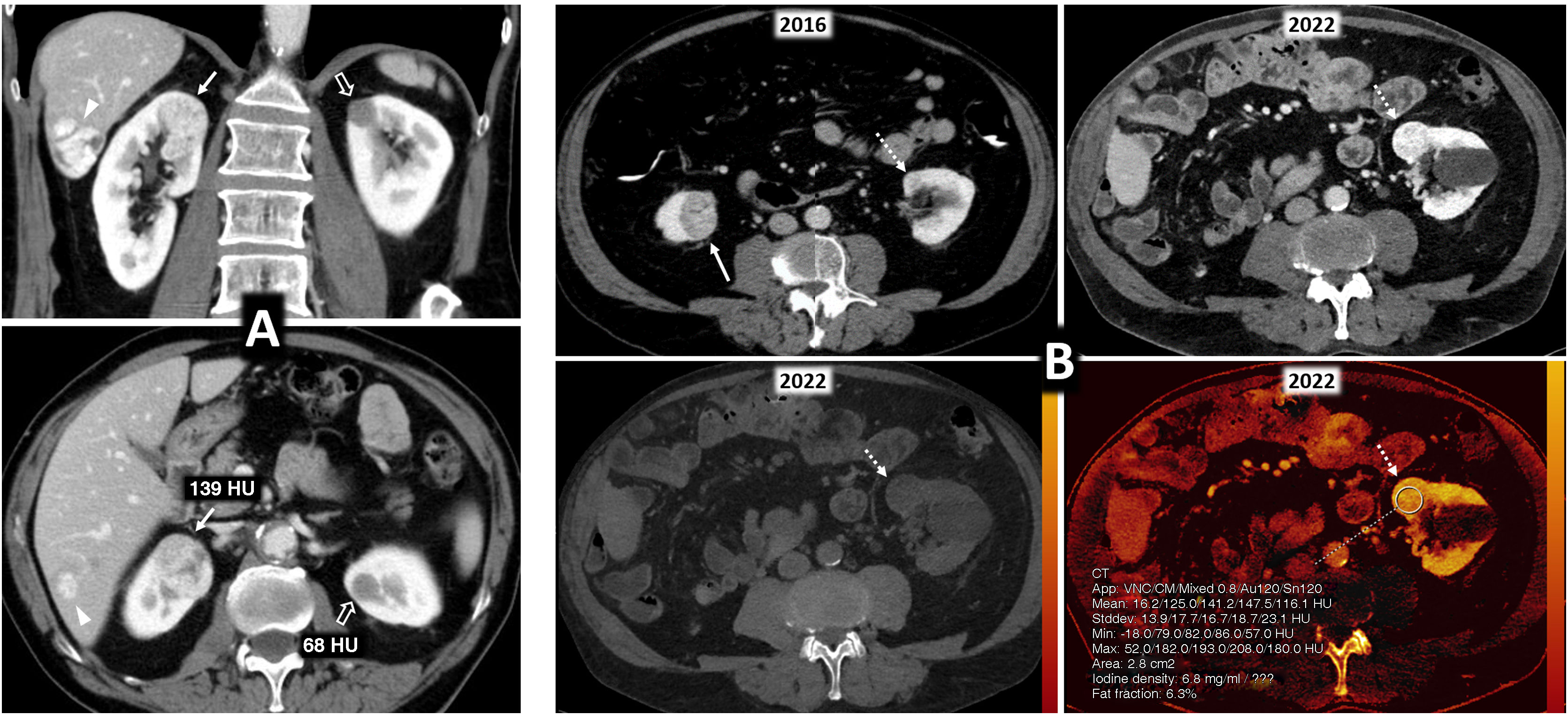

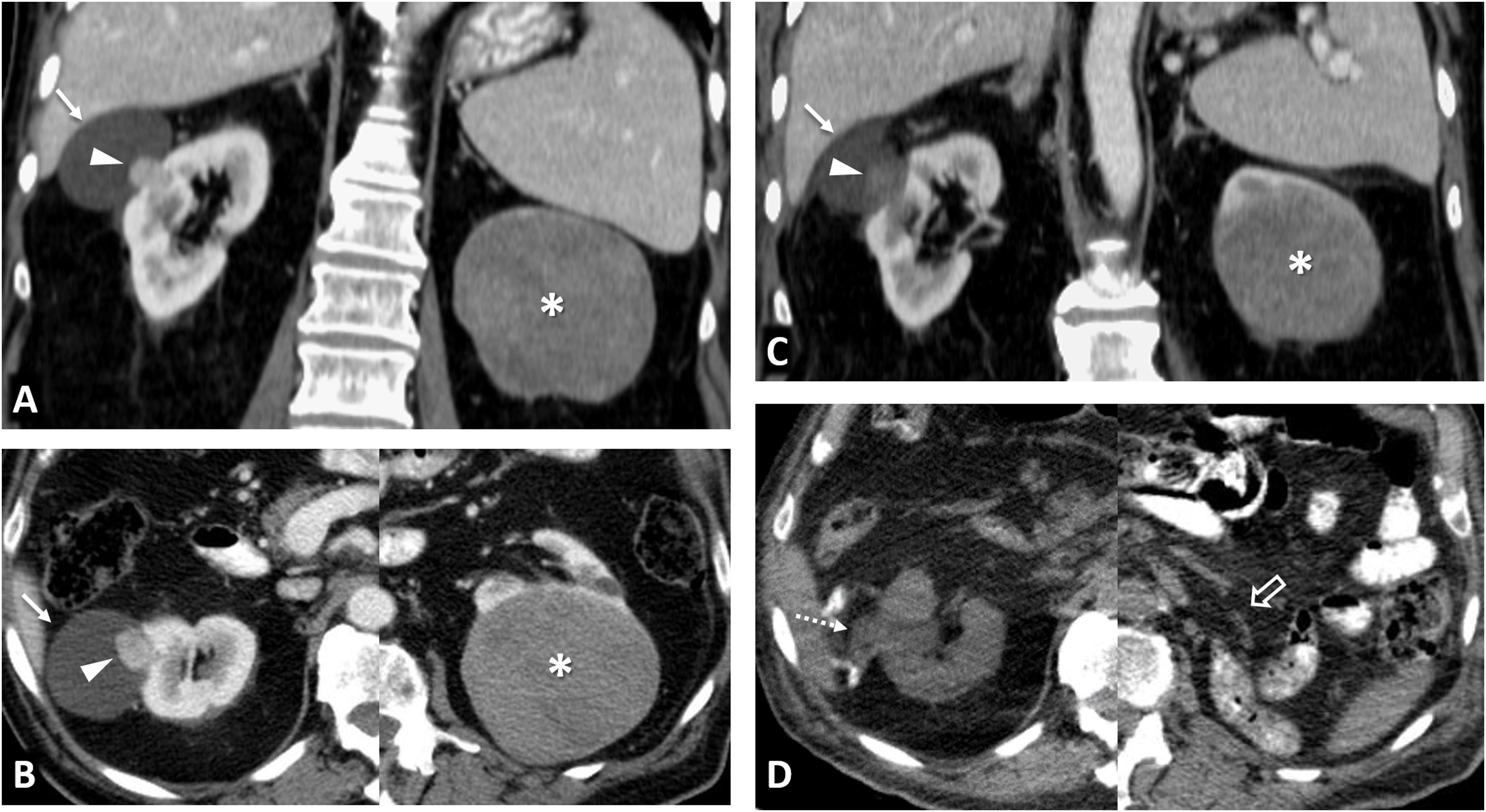

Multiple sporadic bilateral renal tumours with discordant histology. (A) Contralateral clear cell (ccRCC) and papillary carcinomas (pRCC). ccRCC on right (arrows). Lesion with significant enhancement and eccentric necrotic areas on coronal and axial CT images in corticomedullary phase. pRCC on left (hollow arrows). Lesion homogeneously hypoenhancing. Arrowheads: hepatic haemangioma. (A) Contralateral ccRCC and chromophobe carcinomas. Upper left: Baseline CT (axial image in nephrographic phase). Incidental finding of well-demarcated right lower renal nodular lesion with moderate enhancement, less than that of the adjacent renal parenchyma (arrow). A contralateral cortical lesion with more intense enhancement, very similar to that of the renal parenchyma (dashed arrow) was overlooked. A right nephrectomy was performed revealing a pT1a cRCC. A review three years later revealed this lesion, with moderate growth (not shown). Six years after the first study, spectral CT was acquired (upper right: average image; lower left: virtual non-contrast image; lower right: iodine map), which again demonstrated moderate growth during the interval and iodine density of 6.8 mg/mL. Core needle biopsy revealed a pT1a ccRCC following partial nephrectomy.

Several studies have shown that multifocality alone does not worsen prognosis; however, it may be impacted by certain treatment decisions.4–6,9,10,12,13

Hereditary renal cell carcinomaSomatic mutations are very common in sporadic RCC. A hereditary syndrome is defined by the presence of a germline mutation in a recognised suppressor gene that activates different oncogenic pathways. It is probably more common than recognised.1,13,14

Important: the inheritance pattern is almost always autosomal dominant. Both penetrance and the frequency of de novo mutations differ between the different syndromes.

There is no specific clinical-epidemiological network in Spain as there is, for example, in France.14 While costs have been lowered, there are still certain costs and risks associated with genetic testing (whether on a single gene or a poligenic panel) such as the finding of variants of uncertain significance.14,15 Few guidelines exist regarding the selection of patients for genetic testing and counselling. Broadly speaking, testing should be considered in patients aged under 46 years with multiple and/or bilateral RCC, a familial history, associated syndromic clinical data, and certain histologies that will be discussed below.7,8,13–15

Important: As a general rule, non-ionising imaging should be performed initially, nonetheless, the follow-up frequency varies according to the syndrome.16–21 Nephron-sparing surgery or percutaneous ablation of tumours larger than 3 cm can also be considered.5,7,9,12–21

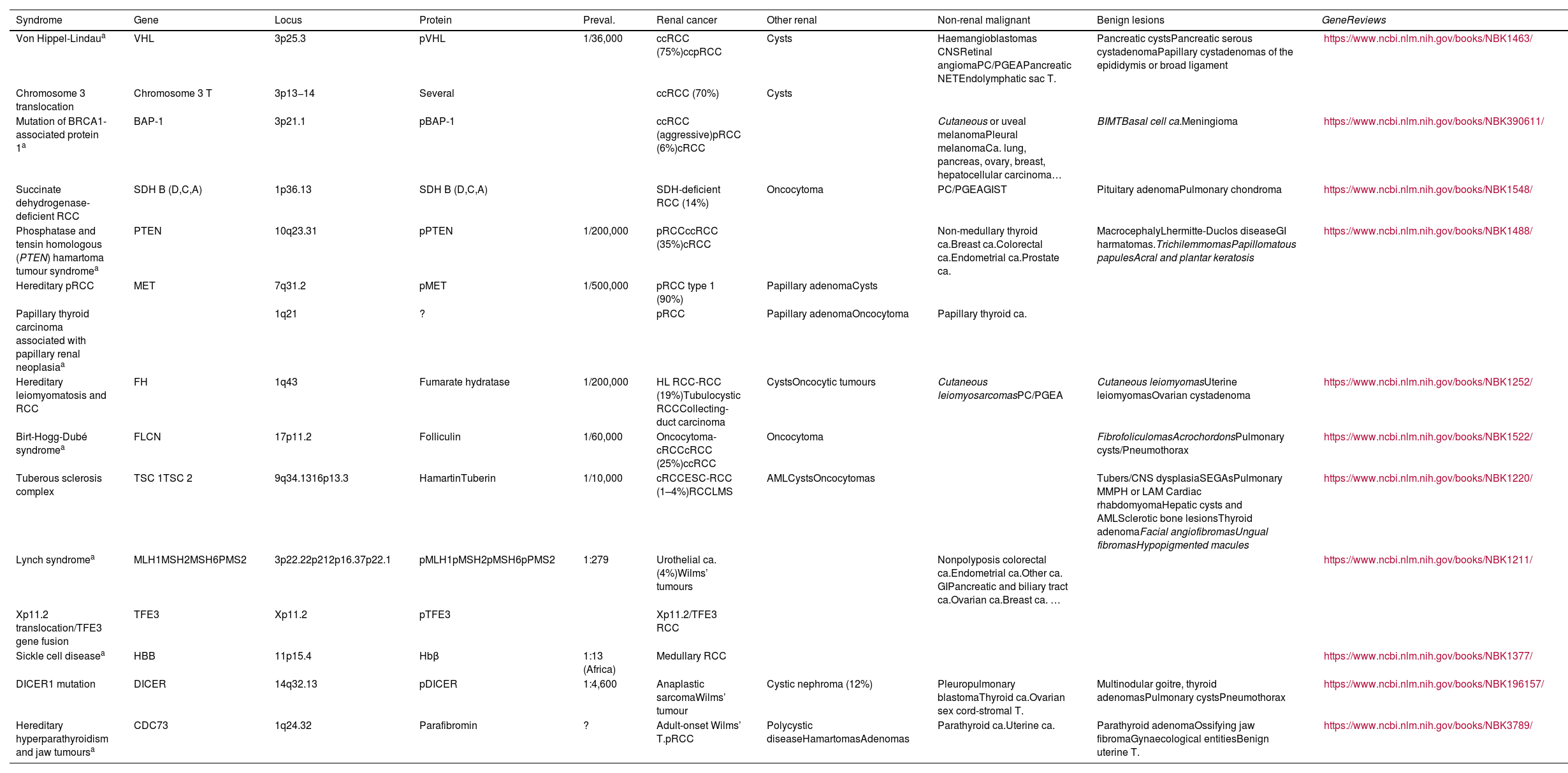

Table 1 lists RCC-related hereditary syndromes and describes their characteristics with links to further information, including diagnostic criteria. The tumour syndrome associated with MITF (including microphthalmia, melanomas and other tumours), mentioned in other articles, is not considered here because recent evidence disproves its direct relationship with RCC.22

Principal hereditary syndromes associated with renal tumours, except syndromes associated specifically with Wilms’ tumours. All are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, except Lynch syndrome (autosomal recessive) and Xp11.2 translocation/TFE3 gene fusion syndrome (Linked to X).

| Syndrome | Gene | Locus | Protein | Preval. | Renal cancer | Other renal | Non-renal malignant | Benign lesions | GeneReviews |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Von Hippel-Lindaua | VHL | 3p25.3 | pVHL | 1/36,000 | ccRCC (75%)ccpRCC | Cysts | Haemangioblastomas CNSRetinal angiomaPC/PGEAPancreatic NETEndolymphatic sac T. | Pancreatic cystsPancreatic serous cystadenomaPapillary cystadenomas of the epididymis or broad ligament | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1463/ |

| Chromosome 3 translocation | Chromosome 3 T | 3p13−14 | Several | ccRCC (70%) | Cysts | ||||

| Mutation of BRCA1-associated protein 1a | BAP-1 | 3p21.1 | pBAP-1 | ccRCC (aggressive)pRCC (6%)cRCC | Cutaneous or uveal melanomaPleural melanomaCa. lung, pancreas, ovary, breast, hepatocellular carcinoma… | BIMTBasal cell ca.Meningioma | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK390611/ | ||

| Succinate dehydrogenase-deficient RCC | SDH B (D,C,A) | 1p36.13 | SDH B (D,C,A) | SDH-deficient RCC (14%) | Oncocytoma | PC/PGEAGIST | Pituitary adenomaPulmonary chondroma | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1548/ | |

| Phosphatase and tensin homologous (PTEN) hamartoma tumour syndromea | PTEN | 10q23.31 | pPTEN | 1/200,000 | pRCCccRCC (35%)cRCC | Non-medullary thyroid ca.Breast ca.Colorectal ca.Endometrial ca.Prostate ca. | MacrocephalyLhermitte-Duclos diseaseGI harmatomas.TrichilemmomasPapillomatous papulesAcral and plantar keratosis | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1488/ | |

| Hereditary pRCC | MET | 7q31.2 | pMET | 1/500,000 | pRCC type 1 (90%) | Papillary adenomaCysts | |||

| Papillary thyroid carcinoma associated with papillary renal neoplasiaa | 1q21 | ? | pRCC | Papillary adenomaOncocytoma | Papillary thyroid ca. | ||||

| Hereditary leiomyomatosis and RCC | FH | 1q43 | Fumarate hydratase | 1/200,000 | HL RCC-RCC (19%)Tubulocystic RCCCollecting-duct carcinoma | CystsOncocytic tumours | Cutaneous leiomyosarcomasPC/PGEA | Cutaneous leiomyomasUterine leiomyomasOvarian cystadenoma | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1252/ |

| Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndromea | FLCN | 17p11.2 | Folliculin | 1/60,000 | Oncocytoma-cRCCcRCC (25%)ccRCC | Oncocytoma | FibrofoliculomasAcrochordonsPulmonary cysts/Pneumothorax | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1522/ | |

| Tuberous sclerosis complex | TSC 1TSC 2 | 9q34.1316p13.3 | HamartinTuberin | 1/10,000 | cRCCESC-RCC (1–4%)RCCLMS | AMLCystsOncocytomas | Tubers/CNS dysplasiaSEGAsPulmonary MMPH or LAM Cardiac rhabdomyomaHepatic cysts and AMLSclerotic bone lesionsThyroid adenomaFacial angiofibromasUngual fibromasHypopigmented macules | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1220/ | |

| Lynch syndromea | MLH1MSH2MSH6PMS2 | 3p22.22p212p16.37p22.1 | pMLH1pMSH2pMSH6pPMS2 | 1:279 | Urothelial ca. (4%)Wilms’ tumours | Nonpolyposis colorectal ca.Endometrial ca.Other ca. GIPancreatic and biliary tract ca.Ovarian ca.Breast ca. … | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1211/ | ||

| Xp11.2 translocation/TFE3 gene fusion | TFE3 | Xp11.2 | pTFE3 | Xp11.2/TFE3 RCC | |||||

| Sickle cell diseasea | HBB | 11p15.4 | Hbβ | 1:13 (Africa) | Medullary RCC | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1377/ | |||

| DICER1 mutation | DICER | 14q32.13 | pDICER | 1:4,600 | Anaplastic sarcomaWilms’ tumour | Cystic nephroma (12%) | Pleuropulmonary blastomaThyroid ca.Ovarian sex cord-stromal T. | Multinodular goitre, thyroid adenomasPulmonary cystsPneumothorax | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK196157/ |

| Hereditary hyperparathyroidism and jaw tumoursa | CDC73 | 1q24.32 | Parafibromin | ? | Adult-onset Wilms’ T.pRCC | Polycystic diseaseHamartomasAdenomas | Parathyroid ca.Uterine ca. | Parathyroid adenomaOssifying jaw fibromaGynaecological entitiesBenign uterine T. | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK3789/ |

AML: angiomyolipoma; Ca: carcinoma; cRRC: chromophobe renal cell carcinoma; ccpRCC: clear cell papillary renal cell carcinoma; ccRCC: clear cell renal cell carcinoma; CNS: central nervous system; ESC-RCC: eosinophilic solid and cystic renal cell carcinoma; GI: gastrointestinal; GIST:gastrointestinal stromal tumour; HL RCC-RCC: hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma-associated renal cell carcinoma; LAM: lymphangioleiomyomatosis; MMPH: multifocal micronodular pneumonocyte hyperplasia; NET: neuroendocrine tumour; RCC: renal cell carcinoma; RCCLMS: renal cell carcinoma with leiomyomatous stroma; PC/PGEA: pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma extraadrenal; pRCC: papillary renal cell carcinoma; SEGA: subependymal giant cell astrocytomas; T: tumour.

Dermatological entities are shown in italics.

GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

In the Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, the loss of the VHL protein generates a situation of pseudohypoxia in which the normal degradation of the alpha subunits of the transcription factors HIF1 and 2 is prevented, activating various oncogenetic factors, mainly by angiogenesis.23 This is the rationale for using anti-angiogenic treatments with sunitinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in cases of sporadic ccRCC, a high percentage of which express somatic mutations in VHL. With a relatively high prevalence and complete penetrance at the age of 60, multiple preneoplastic cystic renal lesions appear (average age of 39) and these are considered ccRCCs when there are three or more cell layers or when a solid nodule appears. De novo mutations account for 20% of these cases. Suspicion is raised when a patient has multiple tumours that are suggestive of ccRCC, particularly if they appear to be cystic and/or the patient is young.

As long as a strict annual MRI or ultrasound imaging schedule is followed from the age of 16, and nephron-sparing surgery is performed on solid tumours exceeding 3 cm in size, (Fig. 3) extrarenal lesions, particularly neurological lesions become the main cause of morbidity and mortality.24 (Fig. 1 of Corral de la Calle et al.)

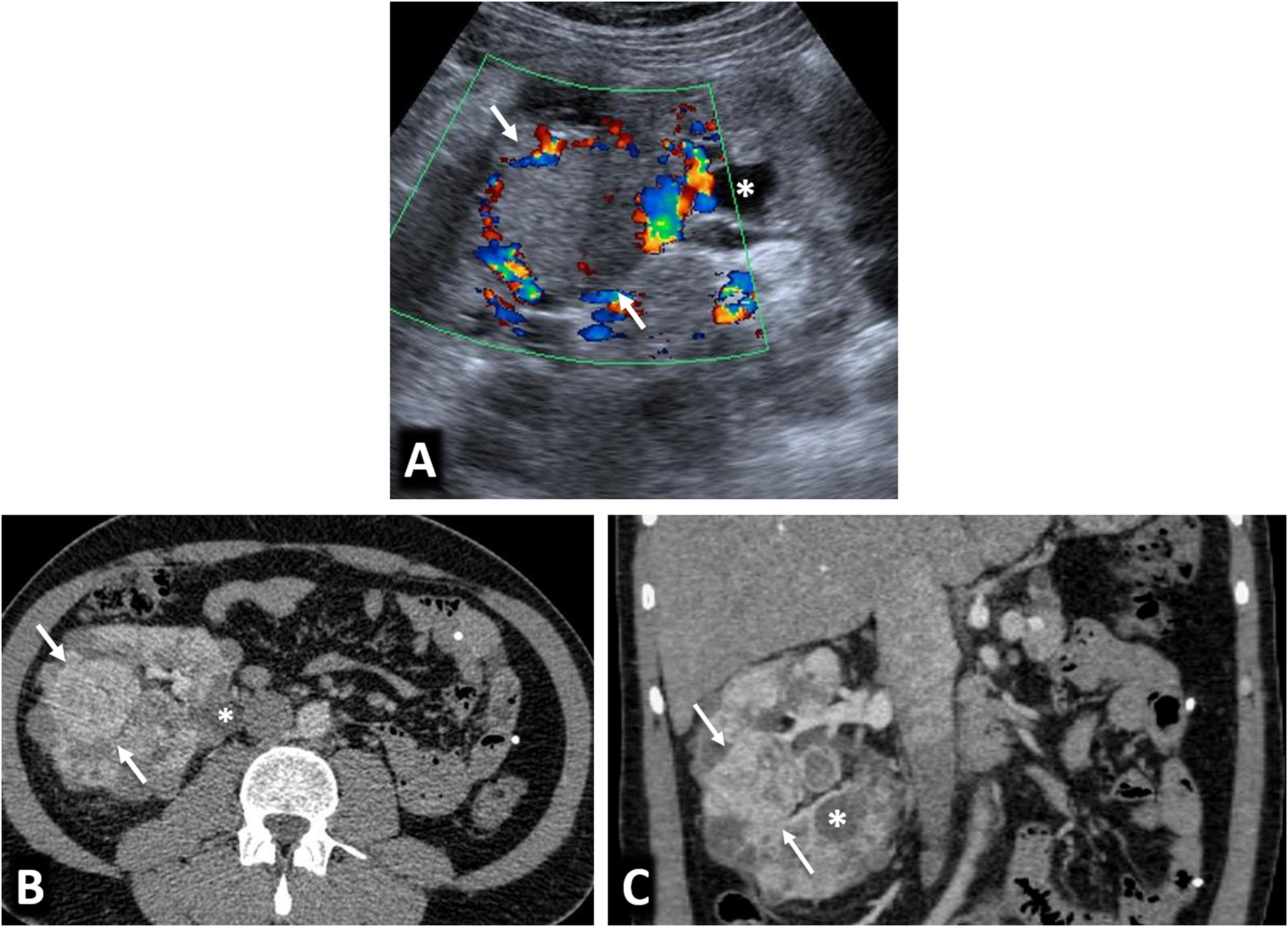

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. A 40-year-old male under follow-up for Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome with a genetic diagnosis and a previous left nephrectomy. In the follow-up with ultrasound and colour Doppler (A), a solid nodular lesion measuring 41 mm (arrows) is detected, confirmed by CT in the nephrographic phase (B and C) and susceptible to selective resection. Renal cysts are also visible (*).

Chromosome 3 translocation is a rare but genetically well-defined entity, and variable points of translocation have been described. Renal cysts and typical ccRCCs appear, with no other signs of VHL. The follow-up and treatment protocols are similar to those used for VHL.14,16

Mutation of BRCA1-associated protein 1This somatic mutation with an oncogenic effect on chromatin is also on the short arm of chromosome 3, and is present in 10–15% of ccRCCs. The syndrome was first defined as the association of pleural mesothelioma with cutaneous or uveal melanoma; other tumours, including ccRCCs, were gradually added in 2013.25

These tumours are more aggressive (often with sarcomatoid features), infiltrating and more prone to venous invasion and distant metastases. They have a worse prognosis and are more radiosensitive (Fig. 4).

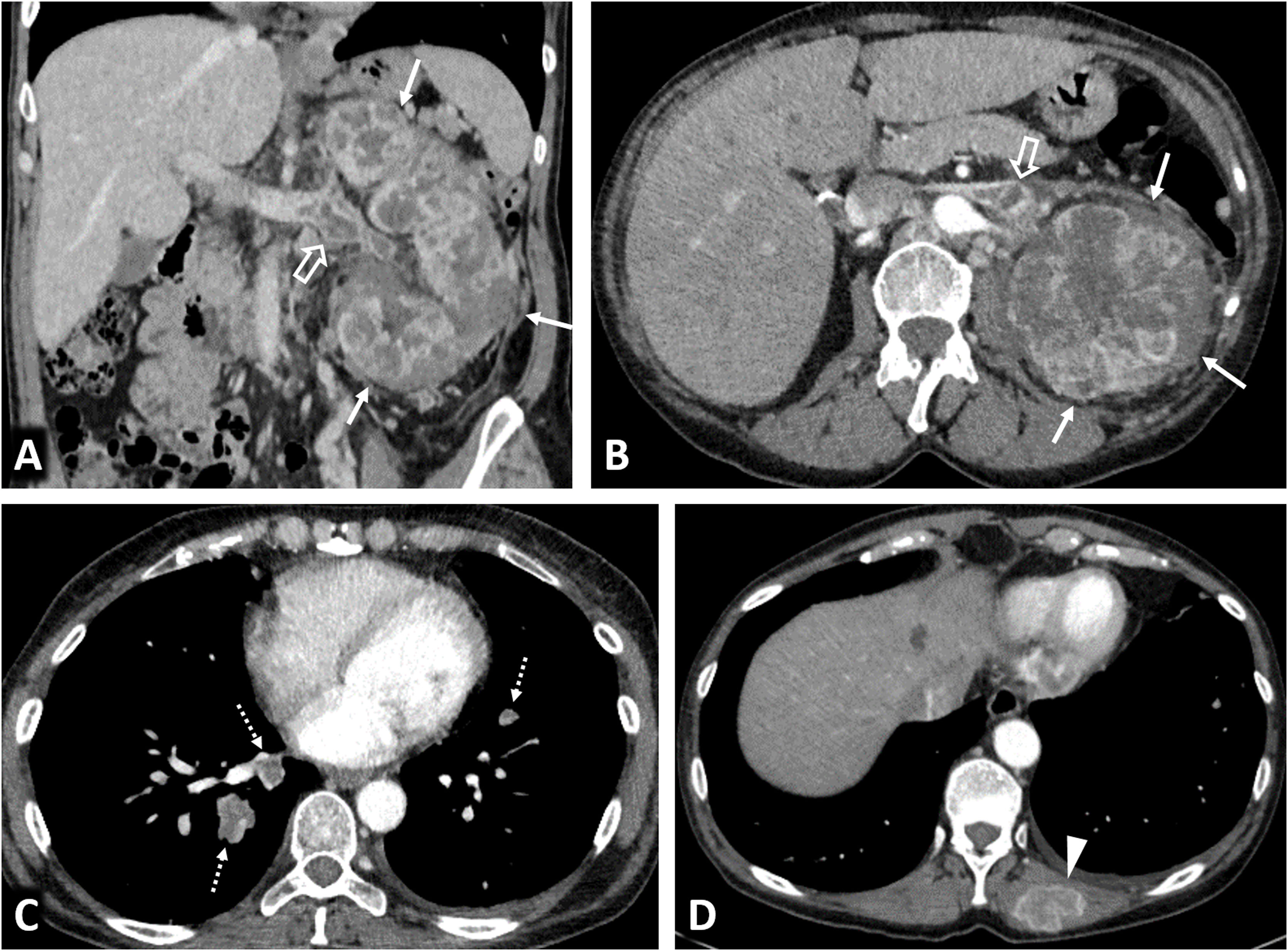

Clear cell renal cell carcinomas (ccRCC) with BAP1 somatic mutation. (A) Coronal CT in nephrographic phase. (B, C and D) Axial CT in corticomedullary phase. A 51-year-old woman with constitutional symptoms and a palpable left lumbar mass. CT shows a left renal tumour with highly infiltrative growth and heterogeneous enhancement (arrows), accompanied by a tumour thrombus in the left renal vein (hollow arrows), as well as pulmonary metastases (dashed arrows) and muscle metastases (arrowhead). Histological examination of the surgical specimen showed a histological grade 4 ccRCC with sarcomatoid features and BAP-1 somatic mutation.

Suggested follow-up involves alternating ultrasound and MRI annually from the age of 30 to detect any RCCs, with conservative treatment being considered as soon as a tumour is detected, due to their poor prognosis.

Succinate dehydrogenase deficient renal cell carcinomaWhile hereditary paraganglioma syndrome can be caused by pathological germline variants in several genes, it is the four subunits of SDH (Krebs cycle enzyme), especially B, that can be associated with RCCs.

Paraganglioma-pheochromocytomas typically appear and are often multiple and bilateral, followed in frequency by GISTs (19%) and RCCs (14%) which appear early and are often multifocal and more aggressive.26 While structurally they resemble ccRCCs, they are listed as a separate entity in the WHO-2016 classification, with a key diagnostic feature being negative immunohistochemistry staining for SDHB in the cell cytoplasm.14

Diagnosis, treatment and follow-up strategies are also more aggressive than for VHL; non-ionising imaging, such as whole-body MRI, is recommended every two years, from around the age of six to eight.

Phosphatase and tensin homologous (PTEN) hamartoma tumour syndromeThe PTEN protein is a tumour suppressor through its dephosphorylating action with a particular effect on the AKT-mTOR pathway. Its germline mutation can lead to several tumour syndromes including Cowden and Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba.

It is associated with dermatological lesions which, in certain combinations, are considered pathognomonic. Major criteria include non-medullary thyroid cancer, breast cancer, endometrial carcinoma and macrocephaly) and minor criteria include RCCs (featuring in more than a third of cases) of different subtypes but predominantly pRCC (Fig. 5). A diagnosis is given when either three minor criteria or two minor and one major criterion are fulfilled.27 Online risk calculators are available (https://www.lerner.ccf.org/genomic-medicine/ccscore/).

PTEN syndrome-associated clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). (A–D) PTEN syndrome. (A) Axial CT scan of the abdomen in the nephrographic phase. (B) Transverse section of ultrasound in B-mode of right hypochondrium. (C) Coronal cervical CT. (D) Photograph of the forehead. An 81-year-old male with haematuria. Physical examination revealed macrocephaly, a mass located at the base of the right side of the cervical region and evident papillomatous facial lesions (D). Imaging studies show several focal right renal lesions with intense enhancement and areas of necrosis (arrows). The largest of these is accompanied by a tumour thrombus, grade 4 in the Mayo clinic classification, which is echogenic and uptakes contrast (*). In addition, a large enhancing mass is visible near the right thyroid lobe (hollow arrows in C). A core needle biopsy was performed on the principal renal mass, which was diagnosed as ccRCC, and on the thyroid mass, which was diagnosed as follicular thyroid cancer, the most frequent histological subtype in this syndrome. The patient died before genetic testing was carried out, but they met the criteria for PTEN syndrome. (E) PTEN syndrome simulator. Coronal CT in nephrographic phase. A 79-year-old female. Lobulated renal mass with intense enhancement and central necrosis (arrows) together with a similar mass near the left thyroid lobe. While PTEN syndrome was suspected, the histological diagnosis was ccRCC with thyroid metastasis. The patient did not meet any other clinical criteria for PTEN.

A MET-activating mutation leads to the overexpression of this transmembrane receptor with tyrosine kinase activity and a regulatory role in proliferation, survival and angiogenesis. Treatment with foretinib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor) has been described as effective. There is MET gain associated with trisomy 7 in 80% of sporadic type 1 pRCCs.

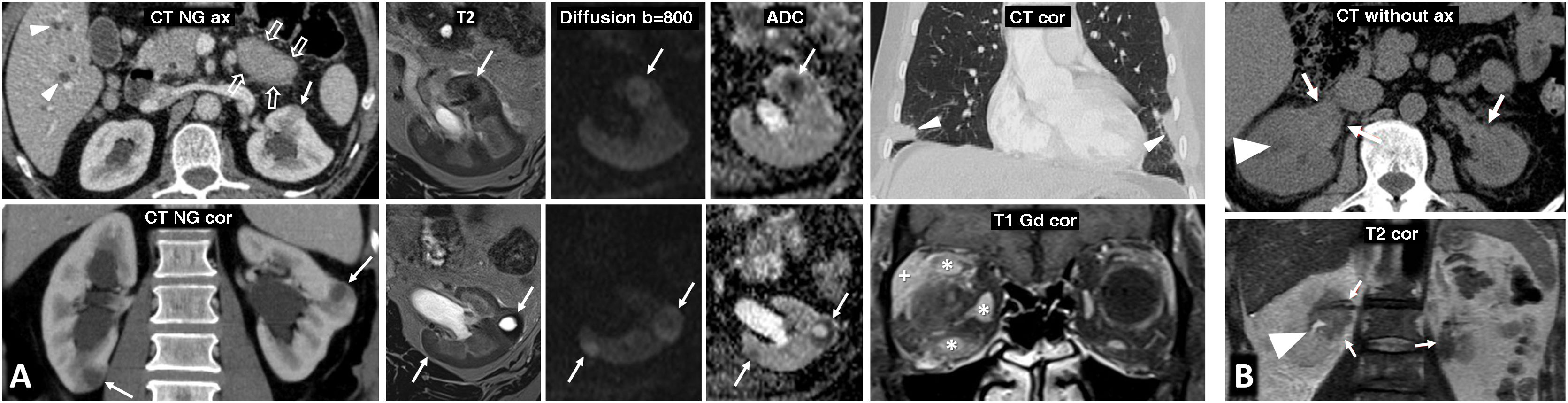

In this rare syndrome, multiple low-grade pRCCs appear in 90% of cases by the age of 80 (median: 43), together with innumerable papillary adenomas that are generally microscopic14 (Fig. 6).

Hereditary papillary renal cell carcinoma (pRCC) in a 74-year-old male. Incidental finding. (A) (coronal) and (B) (axial; composite image). CT in nephrographic phase. Exophytic right renal cystic mass (arrows) with a solid nodule hypoattenuating with respect to the renal parenchyma (arrowheads). There is also an exophytic cortical mass, which is also hypoattenuating, near the contralateral kidney (*). A core needle biopsy of the solid component of the right solid nodule was performed, revealing a pRCC, and so percutaneous radiofrequency thermoablation was performed in the same procedure. (C) Coronal CT in the nephrographic phase one day after ablation. Loss of tension in the right cystic component (arrow) and small residual attenuating image (arrowhead), without enhancement compared to the non-contrast study (not shown). The contralateral lesion (*) showed absolute enhancement of 32 HU and was also suspected to be a pRCC. The urology department decided to perform a left nephrectomy, which confirmed this suspicion. In addition, numerous millimetric papillary adenomas were identified in the left kidney. (D) Axial CT (composite image) without contrast (due to renal failure) five years after nephrectomy. Image showing no recurrence in the right kidney (dashed arrow) and left nephrectomy (hollow arrow).

It shares the same monitoring and treatment strategy as used for VHL.

Papillary thyroid carcinoma associated with papillary renal neoplasiaThis very rare and not widely accepted entity was described in 2000 concerning a family in the United States with papillary thyroid and renal carcinomas, as well as renal adenomas and oncocytomas.28 It was interpreted as familial papillary thyroid cancer, but no description was provided of the gene involved. There are also isolated publications of coincidental cases with no genetic testing and no clear familial association (Fig. 7).

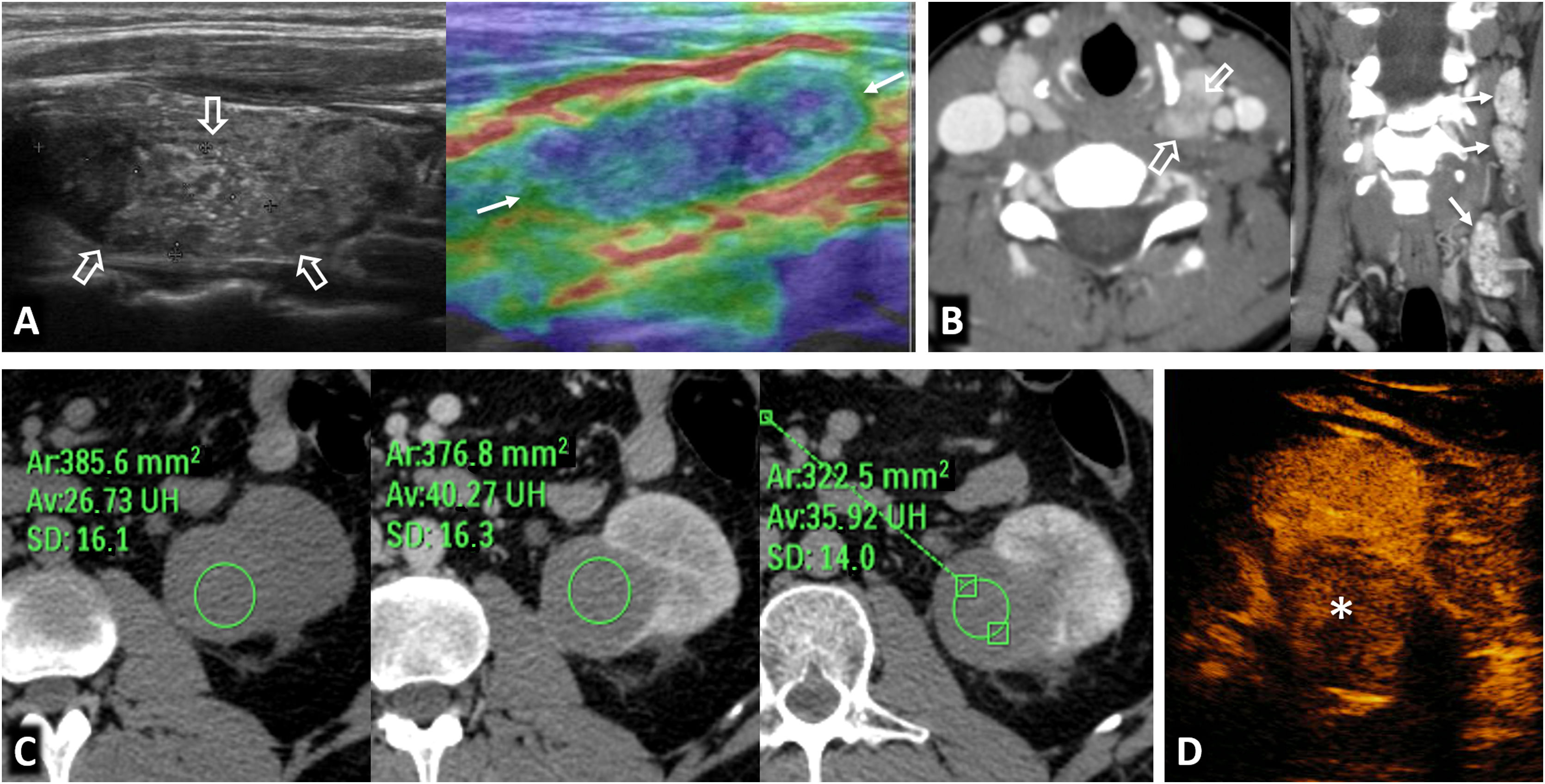

Papillary thyroid carcinoma and papillary renal neoplasia in a 32-year-old female. Palpable enlarged lymph nodes in the neck. (A) B-mode ultrasound of the left thyroid lobe and qualitative strain elastography of the cervical lymph node. (B) Cervical CT (axial and coronal) with intravenous contrast. Hypoattenuating nodular lesion measuring 21 mm with microcalcifications in the left thyroid lobe (hollow arrows) and laterocervical lymphadenopathies, also with microcalcifications and tissue stiffness on qualitative elastography. The histological result after surgical resection was papillary carcinoma with lymph node metastases. (C) CT at the level of the left kidney, without contrast, in the corticomedullary phase and in the nephrographic phase. (D) Non-contrast ultrasound. Axial image captured 55 seconds after contrast administration. Exophytic cortical solid nodular lesion in the left kidney that was slightly hyperattenuating in the baseline study, and discreet enhancement that even raised the possibility of pseudoenhancement on CT (ROI), better seen on contrast-enhanced ultrasound (*), where intralesional ‘bubbles’ could be observed in real time. A partial nephrectomy was performed, which resulted in a diagnosis of papillary renal cell carcinoma. There was no familial aggregation, and no genetic testing was carried out.

This FH germline mutation encodes fumarate hydratase, a Krebs cycle enzyme.

It was reported in 2011 concerning two Finnish families and involves frequent and abundant early cutaneous and uterine leiomyomas, RCC (19%) and exceptionally pheochromocytomas-paragangliomas.

A single, large and aggressive RCC (always histological grade 3) tends to appear around the age of 40–46, with an average survival time of 14–18 months (Fig. 8). It was classified as pRCC type 2 due to its morphology, but it is recognised as a separate entity in the WHO 2016 classification, with its key immunohistochemical feature being the loss of FH expression.14,29

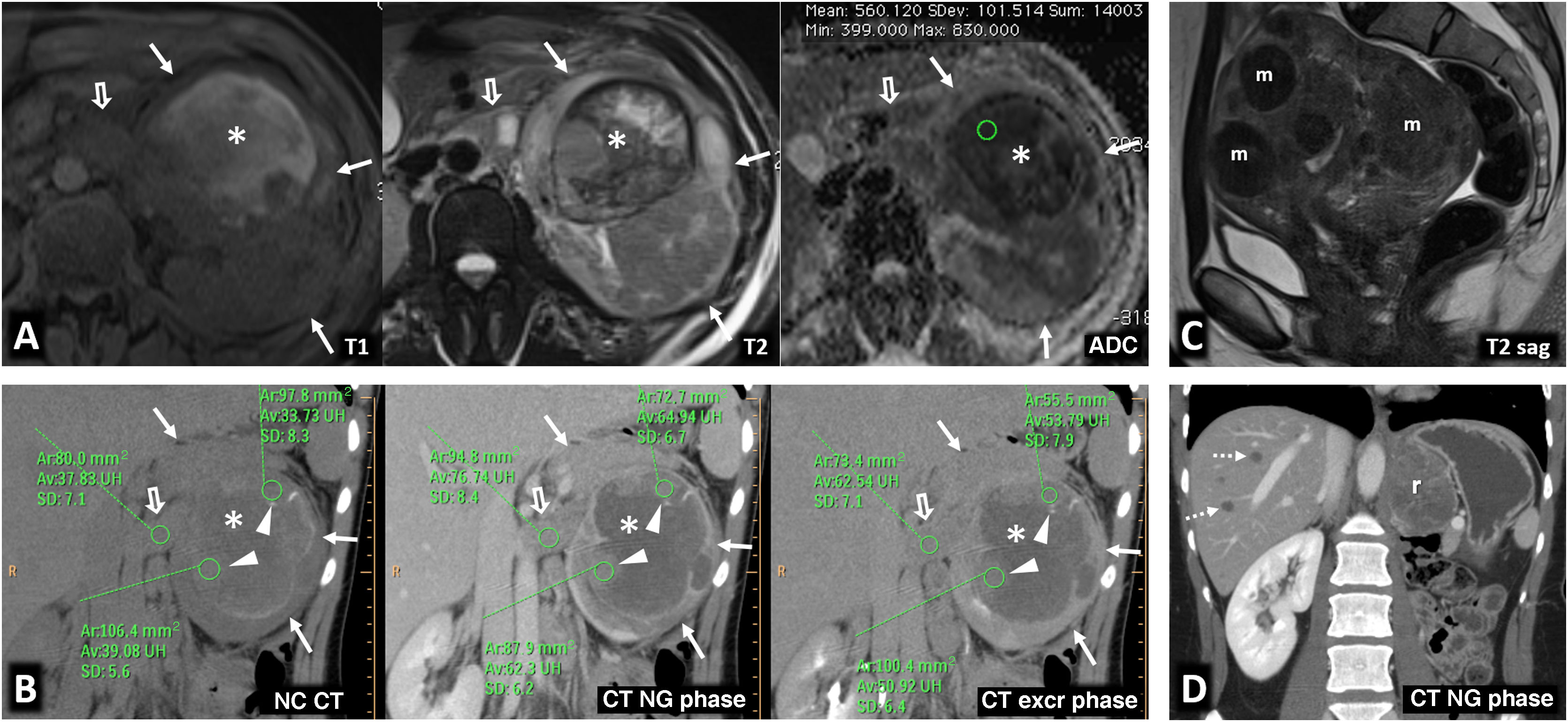

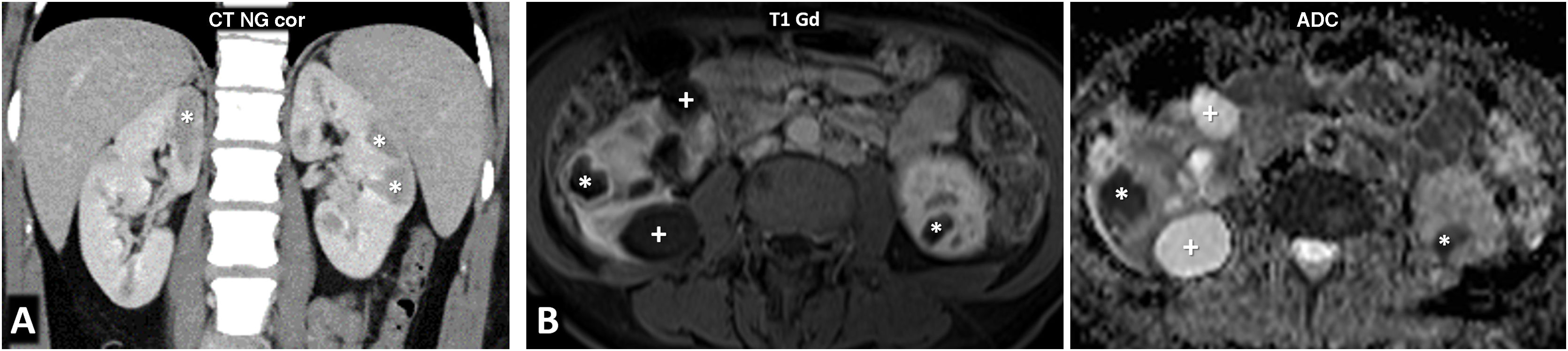

Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma. A 26-year-old female with constitutional symptoms, pain and a palpable mass in the left lumbar region. (A) MRI. Axial images with T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and parametric map of apparent diffusion coefficient. (B) Coronal non-contrast CT, nephrographic phase and excretory phase. Infiltrating mass measuring 135 mm in the left kidney (arrows). There are extensive cystic-necrotic and haemorrhagic areas (*), the latter with high T1 signal and water diffusion restriction, as well as papillary projections with subtle enhancement on CT, with an increase of between 23 and 31 HU in the nephrographic phase (arrowheads). It is accompanied by a tumour thrombus in the left renal vein, with similar characteristics. (C) Sagittal T2-weighted pelvic MRI performed three years earlier. Uterus with multiple hypointense fibroids (m). (D) Coronal CT image in the nephrographic phase one year after nephrectomy. Recurrence in the form of a heterogeneous mass in the surgical site (r) and liver metastases (dashed arrows). The nephrectomy specimen was initially diagnosed as papillary renal cell carcinoma type 2. Later, loss of FH staining was observed in a controlled immunohistochemical study, allowing for the diagnosis of this specific entity.

Management should be more stringent than for VHL.

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndromeFolliculin interacts with the mTOR pathway and mitochondrial metabolism, and a deficiency affects energy homeostasis and cell growth.

The prevalence of this genodermatosis is probably underestimated and involves the development of fibrofolliculomas and acrochordons. Major criteria include more than five folliculomas with at least one being histologically confirmed or a heterozygous pathogenic variant in the FLCN gene. Minor criteria include lung cysts (which may lead to pneumothorax) or RCC with histology in the oncocytoma-chromophobe range, especially multiple or with early onset (Fig. 9). One major or two minor criteria are required for diagnosis.30

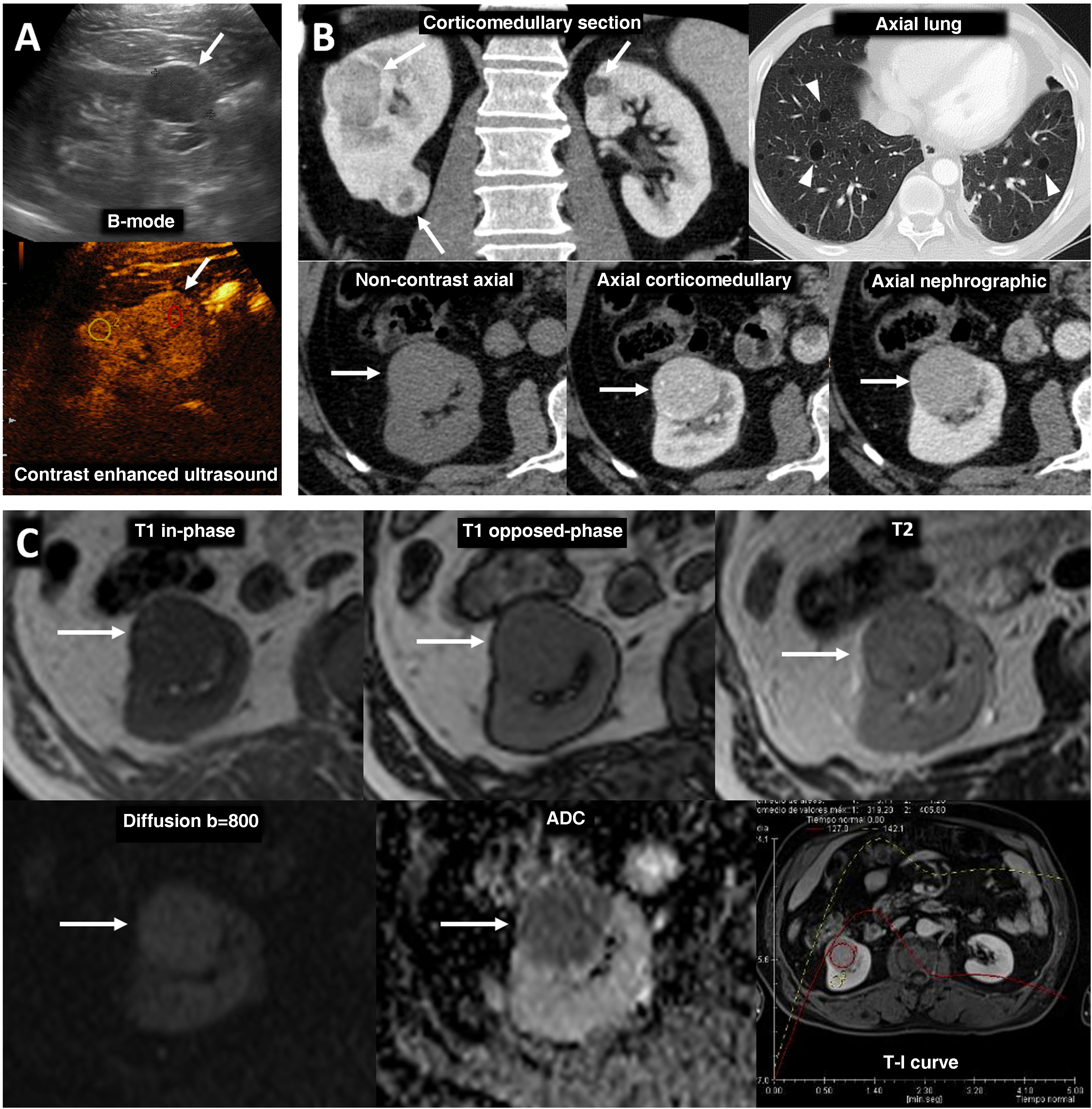

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. A 68-year-old male. Incidental finding in an ultrasound examination. (A) Ultrasound centred on a lesion. In B-mode (arrow) it is discreetly hypoechogenic, with contrast enhancement (red ROI), purely intravascular, almost as intense as that of the renal parenchyma (yellow ROI), both in the static image and in the time-intensity curve (not shown). Core needle biopsy was performed on this lesion and on another lesion (not shown), with histological diagnoses of a chromophobe cell renal carcinoma and an oncocytic lesion. (B) CT Multiple focal bilateral renal lesions of various sizes and well demarcated (at least six were identified) with moderate enhancement, somewhat weaker than that of the renal parenchyma and more intense in the corticomedullary phase (arrows). One had some small focal calcification (not shown). Thin-walled cysts are also visible at the lung bases (arrowheads). (C) MRI centred on the larger lesion (arrows). It shows signal intensity in T1 (similar for in-phase and opposed-phase sequences) and T2, as well as moderate water diffusion restriction, with an average ADC value of 0.91 × 10−3 mm2/s and clearly less intense enhancement than that of the renal parenchyma in the time-intensity curve (ROI and red and yellow curves, respectively). The genetic study confirmed a germline mutation of the FLCN gene in heterozygosis.

Hamartin or tuberin deficiency leads to a deregulation of the inhibition function of the 1-mTOR complex, thus justifying the efficacy of sirolimus or everolimus for some manifestations.

Tuberous sclerosis is a phacomatosis (with neurocutaneous involvement), characteristically involving benign renal lesions, predominantly AMLs, although malignant tumours may be seen in a small percentage of cases, including cRCCs, eosinophilic solid cystic RCCs or RCCs with leiomyomatous stroma.

Most cases are de novo and penetrance is variable.

Morbidity is most commonly caused by neurological involvement or by cardiac rhabdomyomas in the neonatal or foetal period; however, these tend to involute.

Diagnosis requires two major criteria or one major and two minor criteria. Major criteria include multiple AMLs and pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis; however, this combination alone does not meet diagnosis criteria. Minor criteria include sclerosing bone lesions31 (Fig. 10).

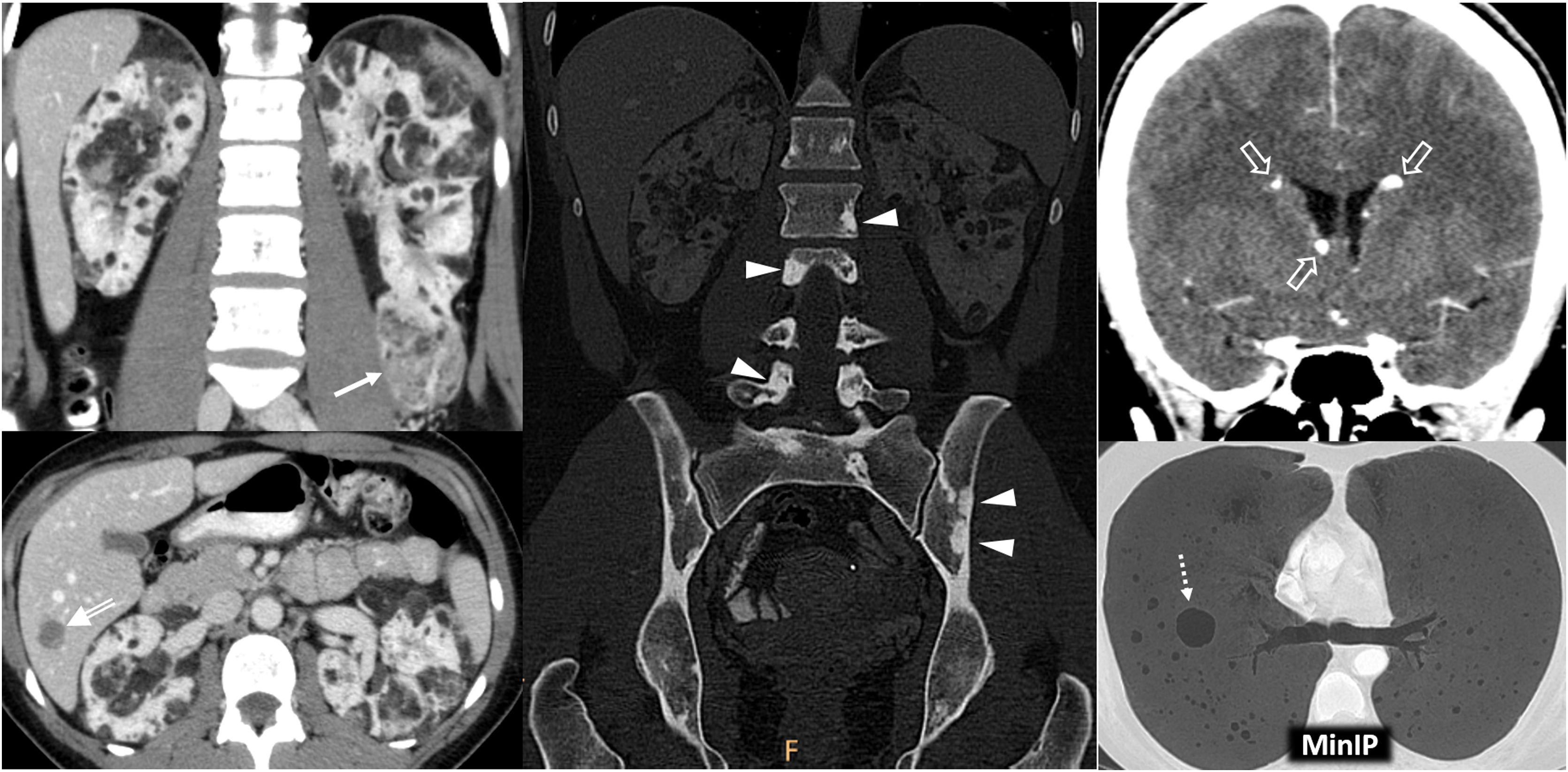

Tuberous Sclerosis Complex in a 45-year-old female. CT. Innumerable bilateral renal angiomyolipomas with gross fat. Its exophytic growth is noteworthy due to the risk of bleeding associated with its size and the abundance of aberrant vessels, one of which is in the lower pole of the left kidney (arrow). Hepatic angiomyolipomas are also visible (double arrow), along with sclerotic lesions in the axial skeleton (arrowheads), small subependymal calcified lesions (hollow arrows) and multiple thin-walled cystic lesions in both lungs (dashed arrow) in the context of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

This syndrome is caused by mutation in four genes involved in DNA mismatch repair, and is highly prevalent.

The third most common neoplasm is urothelial carcinoma, after colorectal and endometrial carcinomas.32 (Fig. 11).

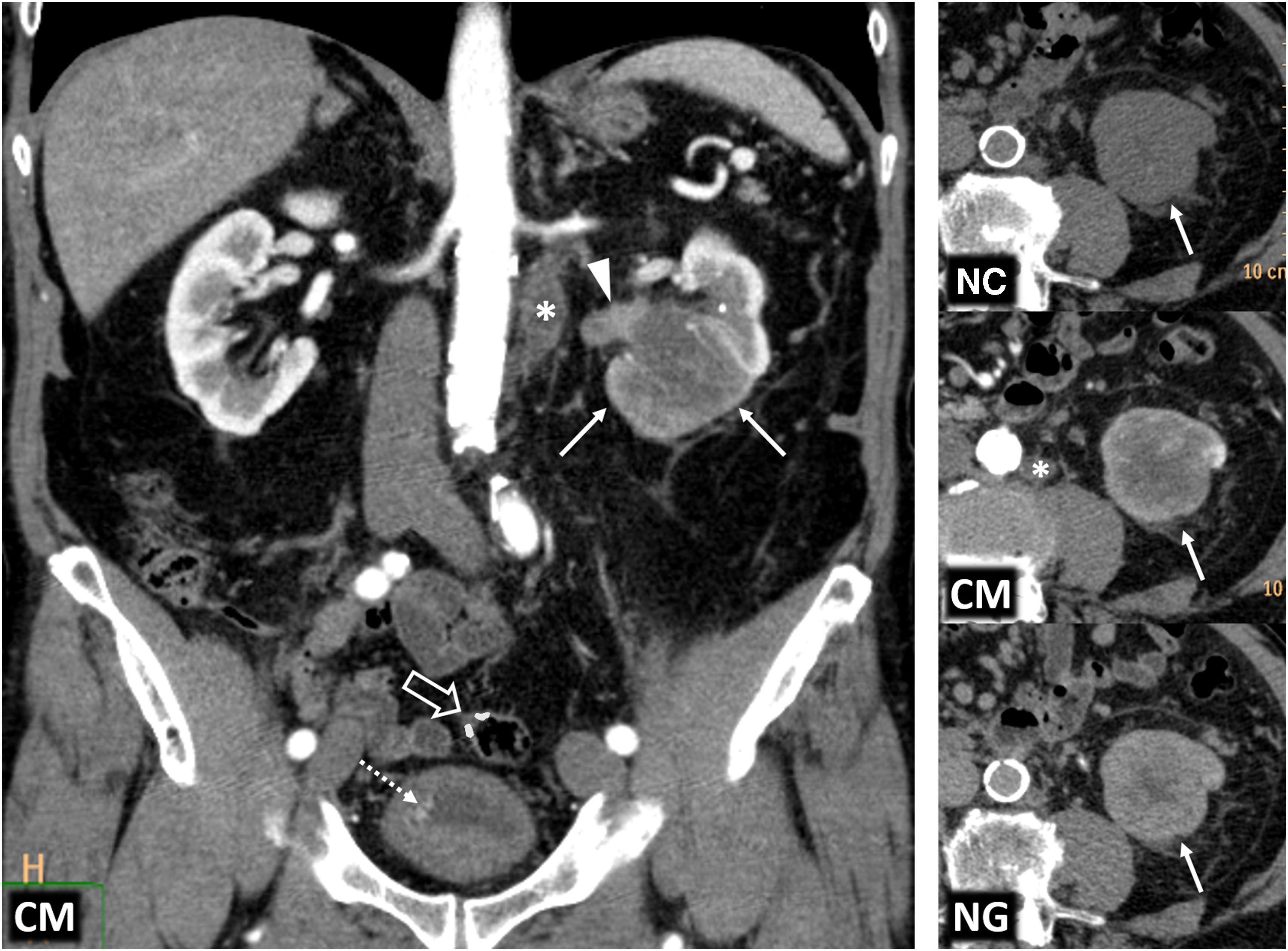

Lynch syndrome in a 73-year-old male who previously underwent surgery for sigmoid colon adenocarcinoma. Haematuria. CT. Mass affecting renal pelvis (arrowhead) and infiltrating renal parenchyma (arrows) with scant enhancement. It corresponded to a urothelial carcinoma accompanied by enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes (*) and a synchronous bladder lesion (dashed arrow). See part of the mechanical colorectal anastomosis (hollow arrow).

An annual urine cytology is recommended from the age of 30, with imaging studies required at least for the MSH2 variant (4% chance of urothelial carcinoma).

Xp11.2 translocation/TFE3 gene fusionXp11.2 translocation/TFE3 gene fusion is associated with a specific subtype of RCC listed in the WHO-2004 classification. It is morphologically similar to ccRCCs in young patients, some of whom have undergone prior chemotherapy, and it has a poorer prognosis. Some imaging descriptions suggest that enhancement is somewhere between that typical of ccRCC and pRCC, while calcifications and pseudocapsules are also visible.33

Sickle cell diseaseSickle cell disease may be associated with medullary RCC, which is almost exclusively found in haemoglobinopathies.34 This central tumour has poor enhancement, and it is typically seen in young African males (average age: 24.3 years), with a mean survival of 13 months.

DICER1 mutationDICER1 mutation is associated with various pleuropulmonary lesions (notably blastomas) as well as thyroid, ovarian and other lesions in children and young people, including cystic nephromas (12%).35

Hereditary hyperparathyroidism and jaw tumoursHereditary hyperparathyroidism and jaw tumours are found within the spectrum of CDC73-associated diseases. Hyperparathyroidism due to parathyroid adenoma is typically seen in adolescents (carcinoma in 10–15%). Other lesions include ossifying fibromas of the jaw (30–40%) and renal lesions (20%), which are generally benign. More rarely, findings include adult-onset Wilms' tumours (WT) or pRCCs.36

Wilms' tumour predisposition syndromesThere is an underlying germline pathogenic variant or epigenetic alteration during early embryogenesis in 10–15% of WT patients. Suspicious features include multifocality, familial history of WT, onset before the age of two years, multiple nephrogenic rests (especially if intralobar) or syndromic clinical symptoms.37 Certain histological findings may indicate specific genetic causes. Some centres recommend genetic testing of all individuals with WT. In individuals at >1% risk of WT, quarterly ultrasound is recommended from birth or time of diagnosis.38

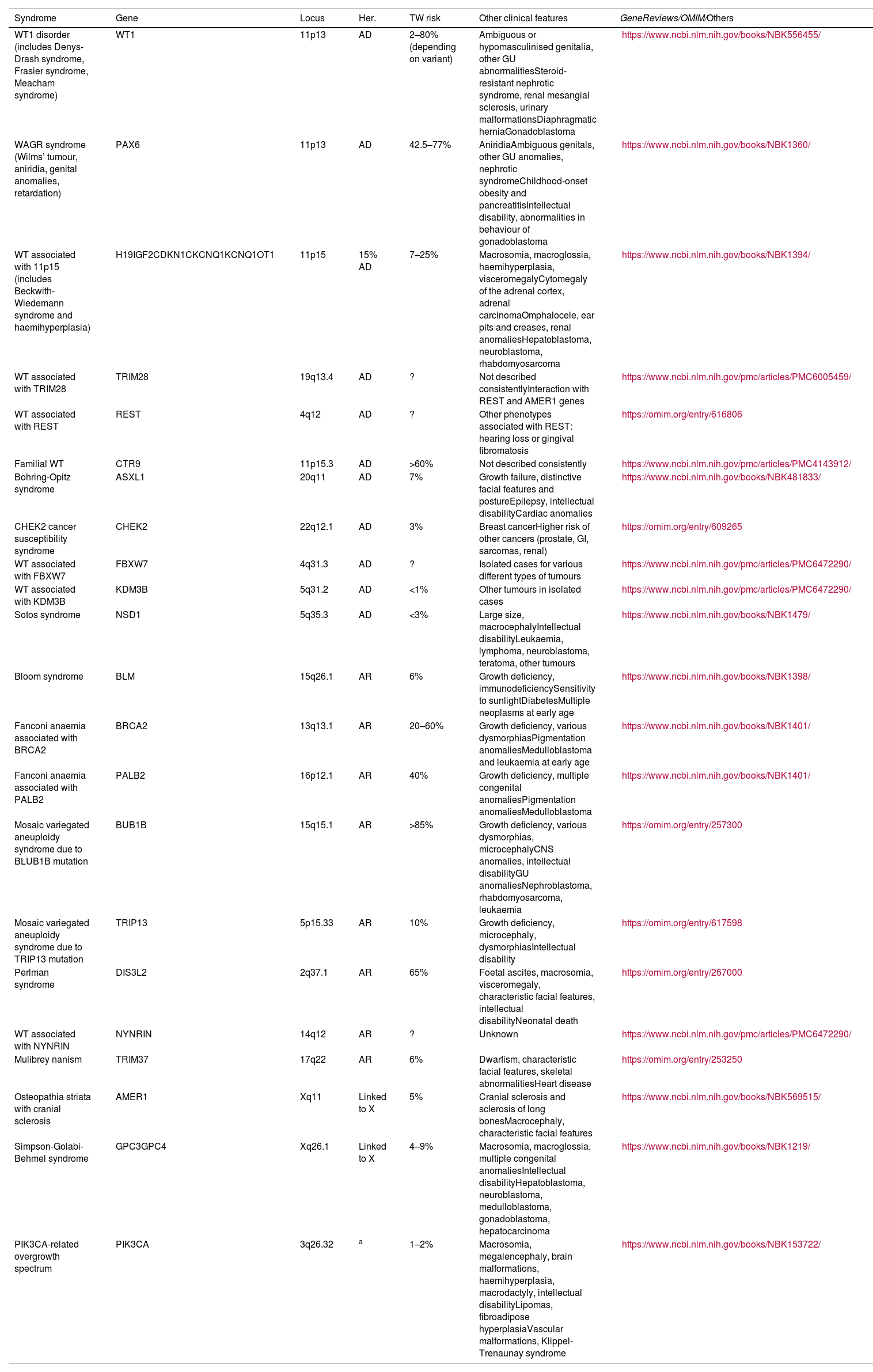

A number of syndromes associated with WT are shown in Table 2. The following are worth noting due to their rarity:

- -

WT1 Disorder. Disorder of sex development with genitourinary anomalies, gonadal dysgenesis, early-onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (average age: 1.5 years), and gonadoblastomas (5%). Slightly early onset of TWs which are also sometimes multifocal (accounting for 1–5% of WTs). Includes various syndromes.39

- -

WAGR syndrome. Caused by an abnormality in the gene adjacent to WT1, which can result in isolated aniridia or this syndrome, the latter of which adds other risks including genitourinary anomalies, intellectual disability and a very high risk of WT (42.5–77%).40

- -

WT associated with 11p15. Of note is the Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, a growth disorder resulting from alterations in different genes in two nearby domains. This syndrome typically includes embryonal tumours (WT in 7–25%, hepatoblastomas, neuroblastomas and rhabdomyosarcomas), adrenocortical cytomegaly (pathognomonic), haemihypertrophy, macrosomia, visceromegaly, macroglossia, omphalocele, ear pits and creases and renal anomalies (medullary dysplasia, nephrocalcinosis, medullary sponge kidney and nephromegaly), among other possible major and minor anomalies.41

- -

WT associated with TRIM28. A specific subtype of WT with monomorphic epithelial histology and negative immunohistochemical staining for TRIM28. Its prognosis is excellent.37

- -

WT associated with REST. Triphasic, blastemal and/or epithelioid WT at an average age of 3.25 years, with no other syndromic data consistently reported.37

Principal hereditary syndromes associated with Wilms’ tumours.

| Syndrome | Gene | Locus | Her. | TW risk | Other clinical features | GeneReviews/OMIM/Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT1 disorder (includes Denys-Drash syndrome, Frasier syndrome, Meacham syndrome) | WT1 | 11p13 | AD | 2–80% (depending on variant) | Ambiguous or hypomasculinised genitalia, other GU abnormalitiesSteroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome, renal mesangial sclerosis, urinary malformationsDiaphragmatic herniaGonadoblastoma | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556455/ |

| WAGR syndrome (Wilms’ tumour, aniridia, genital anomalies, retardation) | PAX6 | 11p13 | AD | 42.5–77% | AniridiaAmbiguous genitals, other GU anomalies, nephrotic syndromeChildhood-onset obesity and pancreatitisIntellectual disability, abnormalities in behaviour of gonadoblastoma | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1360/ |

| WT associated with 11p15 (includes Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and haemihyperplasia) | H19IGF2CDKN1CKCNQ1KCNQ1OT1 | 11p15 | 15% AD | 7–25% | Macrosomia, macroglossia, haemihyperplasia, visceromegalyCytomegaly of the adrenal cortex, adrenal carcinomaOmphalocele, ear pits and creases, renal anomaliesHepatoblastoma, neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1394/ |

| WT associated with TRIM28 | TRIM28 | 19q13.4 | AD | ? | Not described consistentlyInteraction with REST and AMER1 genes | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6005459/ |

| WT associated with REST | REST | 4q12 | AD | ? | Other phenotypes associated with REST: hearing loss or gingival fibromatosis | https://omim.org/entry/616806 |

| Familial WT | CTR9 | 11p15.3 | AD | >60% | Not described consistently | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4143912/ |

| Bohring-Opitz syndrome | ASXL1 | 20q11 | AD | 7% | Growth failure, distinctive facial features and postureEpilepsy, intellectual disabilityCardiac anomalies | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481833/ |

| CHEK2 cancer susceptibility syndrome | CHEK2 | 22q12.1 | AD | 3% | Breast cancerHigher risk of other cancers (prostate, GI, sarcomas, renal) | https://omim.org/entry/609265 |

| WT associated with FBXW7 | FBXW7 | 4q31.3 | AD | ? | Isolated cases for various different types of tumours | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6472290/ |

| WT associated with KDM3B | KDM3B | 5q31.2 | AD | <1% | Other tumours in isolated cases | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6472290/ |

| Sotos syndrome | NSD1 | 5q35.3 | AD | <3% | Large size, macrocephalyIntellectual disabilityLeukaemia, lymphoma, neuroblastoma, teratoma, other tumours | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1479/ |

| Bloom syndrome | BLM | 15q26.1 | AR | 6% | Growth deficiency, immunodeficiencySensitivity to sunlightDiabetesMultiple neoplasms at early age | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1398/ |

| Fanconi anaemia associated with BRCA2 | BRCA2 | 13q13.1 | AR | 20–60% | Growth deficiency, various dysmorphiasPigmentation anomaliesMedulloblastoma and leukaemia at early age | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1401/ |

| Fanconi anaemia associated with PALB2 | PALB2 | 16p12.1 | AR | 40% | Growth deficiency, multiple congenital anomaliesPigmentation anomaliesMedulloblastoma | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1401/ |

| Mosaic variegated aneuploidy syndrome due to BLUB1B mutation | BUB1B | 15q15.1 | AR | >85% | Growth deficiency, various dysmorphias, microcephalyCNS anomalies, intellectual disabilityGU anomaliesNephroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, leukaemia | https://omim.org/entry/257300 |

| Mosaic variegated aneuploidy syndrome due to TRIP13 mutation | TRIP13 | 5p15.33 | AR | 10% | Growth deficiency, microcephaly, dysmorphiasIntellectual disability | https://omim.org/entry/617598 |

| Perlman syndrome | DIS3L2 | 2q37.1 | AR | 65% | Foetal ascites, macrosomia, visceromegaly, characteristic facial features, intellectual disabilityNeonatal death | https://omim.org/entry/267000 |

| WT associated with NYNRIN | NYNRIN | 14q12 | AR | ? | Unknown | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6472290/ |

| Mulibrey nanism | TRIM37 | 17q22 | AR | 6% | Dwarfism, characteristic facial features, skeletal abnormalitiesHeart disease | https://omim.org/entry/253250 |

| Osteopathia striata with cranial sclerosis | AMER1 | Xq11 | Linked to X | 5% | Cranial sclerosis and sclerosis of long bonesMacrocephaly, characteristic facial features | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK569515/ |

| Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome | GPC3GPC4 | Xq26.1 | Linked to X | 4–9% | Macrosomia, macroglossia, multiple congenital anomaliesIntellectual disabilityHepatoblastoma, neuroblastoma, medulloblastoma, gonadoblastoma, hepatocarcinoma | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1219/ |

| PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum | PIK3CA | 3q26.32 | a | 1–2% | Macrosomia, megalencephaly, brain malformations, haemihyperplasia, macrodactyly, intellectual disabilityLipomas, fibroadipose hyperplasiaVascular malformations, Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK153722/ |

AD: autosomal dominant; AR: autosomal recessive; Lkd to X: linked to X; WT: Wilms' tumour.

Adapted from: Turner et al.37

GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

OMIM® - Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man®. Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

RCCs are considered non-hereditary when two or more family members have coexisting RCCs (especially if multiple and/or in young people) with no underlying syndrome. Hypotheses to justify its existence include shared environmental factors, polygenic or autosomal recessive inheritance or inherited syndromes yet to be described.

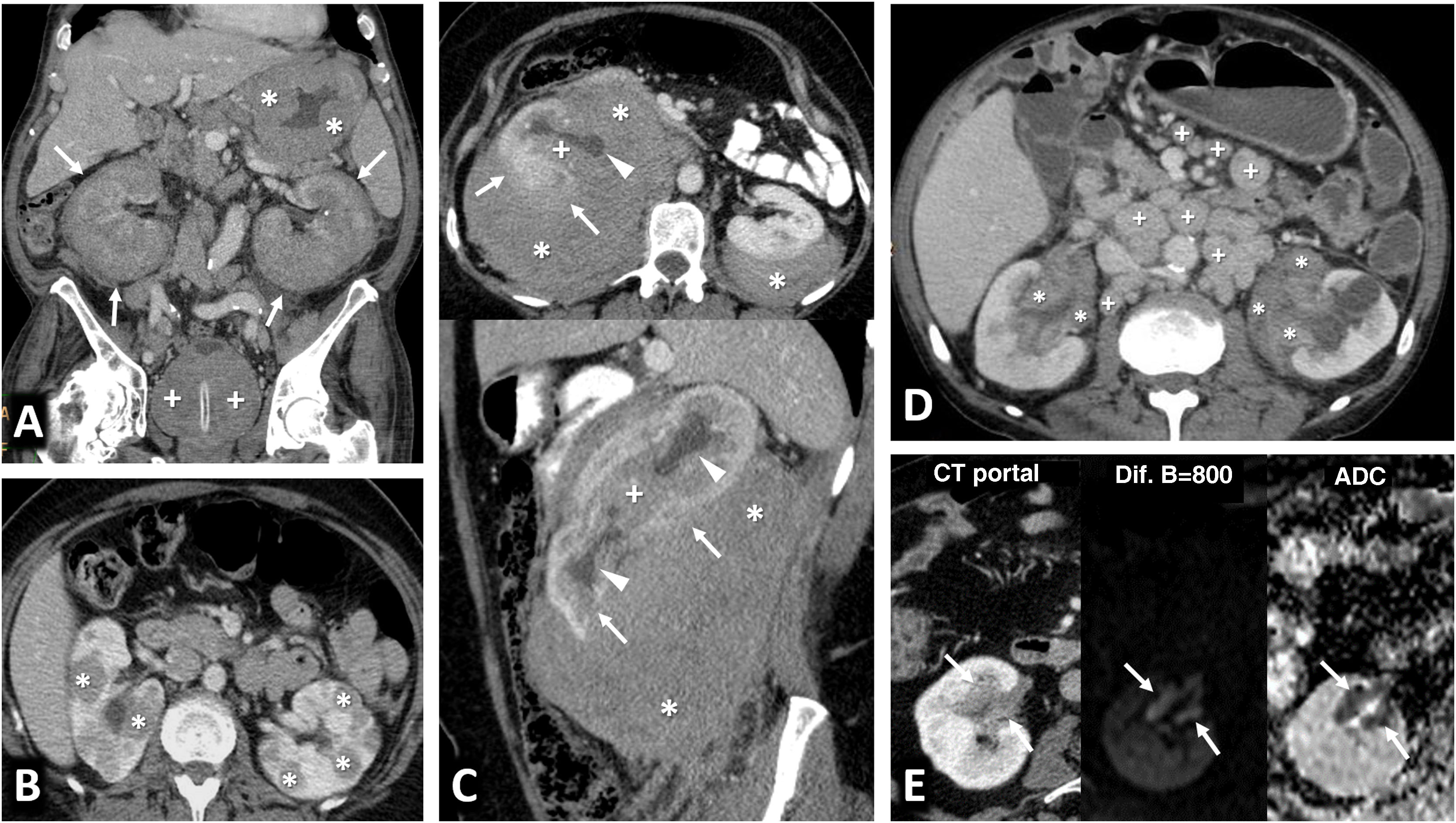

Renal metastasesThe kidney is the eighth most common organ in which metastases occur, with the lung being the most common primary organ. This is seen on imaging in 0.9% of cases (7–20% in autopsies), slightly above the frequency of incidental RCC (0.6%), usually in the context of advanced oncological disease. Although dependent on the primary tumour, growth is generally faster, behaviour tends to be more infiltrative and endophytic, and enhancement is poorer and later than for RCCs42 (Fig. 12).

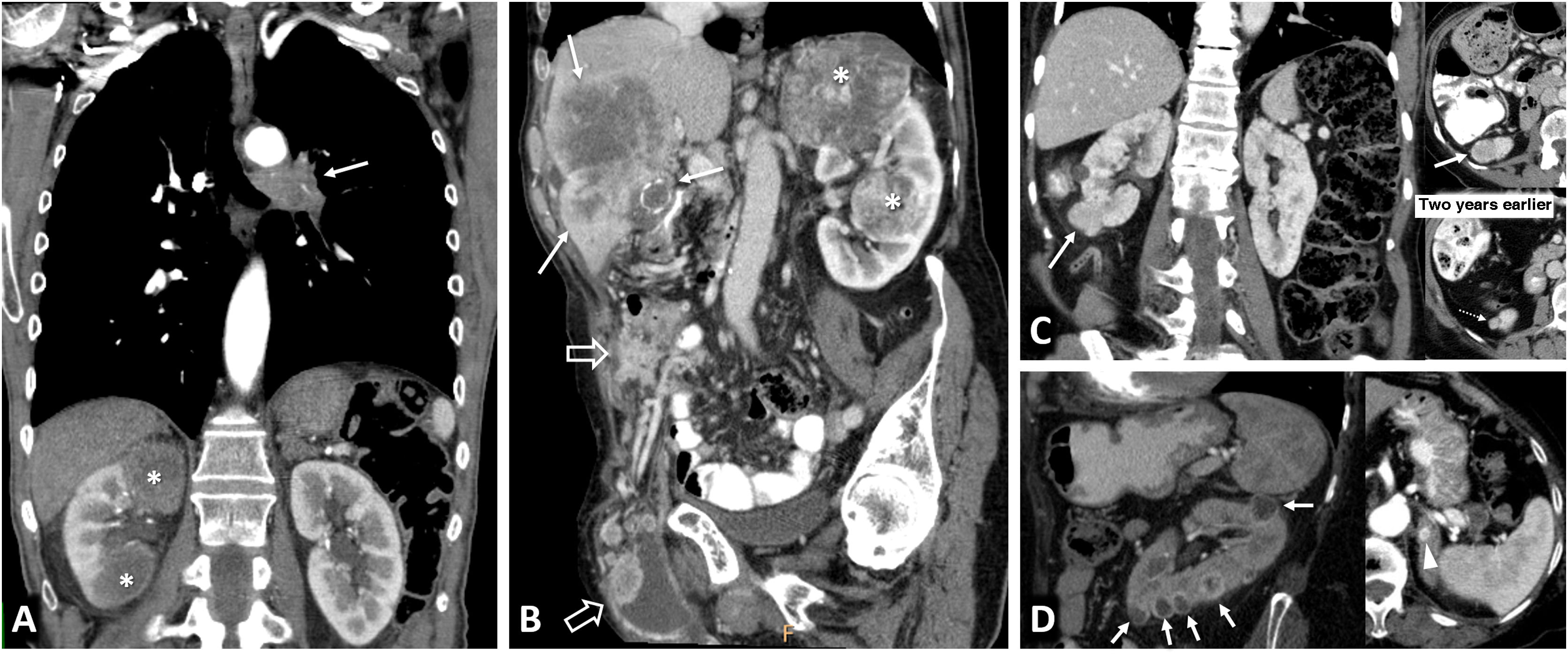

Renal metastases and mimics. (A) Renal metastases of squamous-cell carcinoma of the lung (arrow), exhibiting multiple renal masses with poor enhancement and infiltrative behaviour (*). (B) Renal metastases of adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder with extensive infiltration of the adjacent liver parenchyma (arrows) and extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis, also within an inguinal hernia (hollow arrows). The renal lesions (*) behave similarly to the primary neoplasm, with moderately intense and heterogeneous enhancement, and abundant tumour necrosis. In this case, the lesions have a more expansive behaviour. (C) Clear cell renal cell carcinoma mimicking breast carcinoma metastasis in a 64-year-old woman undergoing oncological follow-up due to her medical history. Exophytic, expansive renal cortical lesion with enhancement almost as intense as that of the parenchyma (arrows). A retrospective review of previous studies showed that it was present in a study performed two years earlier (dashed arrow), with slower growth than expected for metastasis. The diagnosis was confirmed following percutaneous biopsy and tumour removal. (D) Contralateral renal metastases of clear cell carcinoma (ccRCC) or Von Hippel-Lindau? An 82-year-old female underwent a right nephrectomy for ccRCC. CT images show numerous markedly enhancing contralateral renal nodules with cystic appearance and thick walls, which is the usual appearance of lesions in Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. However, hypervascular metastases coexisted in both the left adrenal region (arrowhead) and lung (not shown). The patient died without a confirmatory genetic diagnosis.

Lymphomas, usually of the B-cell non-Hodgkin variety, have renal involvement that has been radiologically confirmed in 1–8% of cases (30–60% in autopsies). They are usually bilateral and involve lymph node and/or other organ disease. In the literature, diffuse infiltration is the most common histological pattern, and imaging reports most frequently describe multifocal lesions.43 In our experience, perirenal infiltration is the most common pattern, often extending into the renal sinus. The lesions are infiltrative, homogeneous and hypoenhancing with marked diffusion restriction (Fig. 13). Similar findings are seen in certain types of leukaemia.

Renal lymphoma. (A) Diffuse infiltration of both kidneys (arrows), in addition to infiltration also demonstrated by a lymphoma of the prostate (+), with the stem of a bladder catheter in its urethral section, and a lymphoma of the gastric wall (*). (B) Multiple and bilateral nodules with discrete enhancement (*). (C) Perirenal solid masses (*) with discrete enhancement, which infiltrate the superficial renal parenchyma (arrows) and penetrate the renal sinus (+), causing discrete hydronephrosis (arrowheads), albeit sparing the vessels (not shown). (D) Peripelvic and renal sinus infiltration (*), in this case accompanied by abundant retroperitoneal and mesenteric lymphadenopathies (+). (E) Infiltration of the renal sinus, with significant water diffusion restriction, high signal in the diffusion sequence with B = 800 s/m2 and low signal in the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map (arrows).

Benign multifocal renal lesions that may mimic tumours can be seen in Figs. 14 and 15.

Multiple benign lesions that may mimic tumours. Acute multifocal bilateral pyelonephritis. CT coronal. Multiple foci with poor enhancement in the form of triangles with a peripheral base in a young febrile woman. (B) Multiple renal abscesses (*) on MRI, with peripheral linear enhancement and restriction of water diffusion within. Very low signal on the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map, in contrast to that of simple cysts (+), with no enhancement of the walls or restricted diffusion.

Multiple benign lesions that may mimic tumours. IgG4-related disease. (A) Lymph node involvement. Small, occasionally triangular, renal cortical nodular lesions are hypoenhancing on CT, with low T2 signal and restricted water diffusion (arrows). One contains a small cyst. Other features related to the involvement of this entity include: autoimmune pancreatitis with tumefaction, absence of superficial crypts and subtle halo around the pancreatic tail (hollow arrows), IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis, with secondary dilatation of the intrahepatic biliary tract (arrowheads), peripheral opacities in both lung bases (arrowheads) and orbital involvement, with enhancing infiltration on MRI of the lacrimal gland (+), the extraocular musculature (*) and to a lesser extent of the orbital fat itself. All lesions responded to steroid therapy. (B) Perirenal involvement. Bilateral peripelvic infiltrative lesion mildly hyperattenuating on non-contrast CT and hypointense on T2 (arrows), with left renal hypotrophy and right calyceal dilatation (arrowheads).

This entity appears as triangular hypovascular focal lesions with a peripheral base and a striated nephrogram44 in a febrile patient.

Multiple renal abscessesEvolving from pyelonephritis, these cystic lesions have enhancing walls and restricted diffusion inside.

Multiple renal infarctionsThese lesions are similar to pyelonephritis but exist in a different clinical context and exhibit late hyperenhancement.

IgG4-related diseaseIgG4-realted disease affects the kidneys in 35% of cases. There are five reported patterns. The most common involves round or triangular hypoenhancing cortical lesions which are hypointense on T2 with restricted diffusion, underlying interstitial nephritis and occasionally membranous glomerulonephritis. It may also appear as a perirenal soft-tissue halo that mimics a lymphoma. There are often co-existing lesions in other organs and elevated serum IgG4.45

ConclusionsMultiple renal tumours and pseudotumour lesions are not that rare. Each lesion should be considered individually and assessed within its broader context in a multidisciplinary manner.

A renal tumour in a neoplastic patient may be primary or secondary. Certain features may support the diagnosis.

In the case of multiple tumours, in young people or individuals with certain syndromic associations, the possibility of hereditary RCC should be considered.

Diagnostic and therapeutic management should be conservative in terms of radiation exposure and nephron protection, and it should be adapted to each circumstance.

Author contributionsResearch coordinators, concept and design: MACC.

Data collection: MACC, JEI, GCFP, AF and MRC. Data analysis and interpretation: MACC, JEI, GCFP, AF and MRC. Literature search: MACC, JEI and GCFP.

Drafting of article: MACC, JEI.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: MACC, JEI, GCFP, AF and MRC.

Approval of the final version: MACC, JEI, GCFP, AF and MRC.

FundingWe have not received any funding from any person or organisation for the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interestNone.