To describe the epidemiology and CT findings for nontuberculous mycobacterial lung infections and outcomes depending on the treatment.

Material and methodsWe retrospectively studied 131 consecutive patients with positive cultures for nontuberculous mycobacteria between 2005 and 2016. We selected those who met the criteria for nontuberculous mycobacterial lung infection. We analysed the epidemiologic data; clinical, microbiological, and radiological findings; treatment; and outcome according to treatment.

ResultsWe included 34 patients (mean age, 55 y; 67.6% men); 50% were immunodepressed (58.8% of these were HIV+), 20.6% had COPD, 5.9% had known tumors, 5.9% had cystic fibrosis, and 29.4% had no comorbidities. We found that 20.6% had a history of tuberculosis and 20.6% were also infected with other microorganisms. Mycobacterium avium complex was the most frequently isolated germ (52.9%); 7 (20.6%) were also infected with other organisms. The most common CT findings were nodules (64.7%), tree-in-bud pattern (61.8%), centrilobular nodules (44.1 %), consolidations (41.2%), bronchiectasis (35.3%), and cavities (32.4%). We compared findings between men and women and between immunodepressed and immunocompetent patients. Treatment was antituberculosis drugs in 67.6% of patients (72% of whom showed improvement) and conventional antibiotics in 20.6% (all of whom showed radiologic improvement).

ConclusionThe diagnosis of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung infections is complex. The clinical and radiologic findings are nonspecific and a significant percentage of pateints can have other, concomitant infections.

Describir la epidemiología y hallazgos en tomografía computarizada (TC) de las infecciones pulmonares por micobacterias no tuberculosas (IPMNT) y su evolución según el tratamiento.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo de 131 pacientes consecutivos con cultivos positivos para micobacterias no tuberculosas (MNT) entre 2005 y 2016. Se seleccionaron los que cumplían con los criterios diagnósticos de IPMNT. Se analizaron los datos epidemiológicos, clínicos, microbiológicos, radiológicos, el tratamiento recibido y la evolución en función de este.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 34 pacientes con una edad media de 55 años, el 67,6% hombres. El 50% estaba inmunodeprimido (VIH positivos, el 58,8%); el 20,6% tenía EPOC; el 5,9%, neoplasias conocidas; el 5,9%, fibrosis quística; y el 29,4% no presentaba comorbilidades. El 20,6% presentaba antecedentes de tuberculosis y el 20,6% estaba infectado por otros microorganismos. Mycobacterium avium complex fue el germen más frecuentemente aislado (52,9%). Siete pacientes (20,6%) presentaron además infecciones por otros microorganismos. En la TC, los hallazgos más frecuentes fueron: nódulos (64,7%), patrón en árbol en brote (61,8%), nódulos centrolobulillares (44,1%), consolidaciones (41,2%), bronquiectasias (35,3%) y cavidades (32,4%). Se realizó un estudio comparativo de los hallazgos entre hombres y mujeres y entre pacientes inmunodeprimidos e inmunocompetentes. El 67,6% recibió antituberculostáticos (el 72% mostró mejoría) y el 20,6%, antibióticos convencionales (todos con mejoría radiológica).

ConclusiónEl diagnóstico de la IPMNT es complejo. Los hallazgos clínicos y radiológicos son inespecíficos y un porcentaje importante de pacientes puede presentar otras infecciones concomitantes.

Interest in nontuberculous mycobacterial lung infection (NTMLI) has increased in recent years mainly for three reasons: the association of NTMLI with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS); the increase in NTMLI in immunocompetent patients, mainly in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); and the increased sensitivity of diagnostic tests.1,2

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are microorganisms widely distributed in our environment which can be isolated from both water and soil.2–4 They are environmental opportunistic pathogens which frequently colonise the human respiratory system5 (particularly in patients with chronic lung disease),4,6 so isolation in a sputum sample or bronchoalveolar lavage should not always be considered pathological, as predisposing factors in the host are required for disease progression.2

This often makes diagnosis difficult, and for this reason the American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America (ATS/IDSA) have established clinical, radiological and microbiological criteria which have to be met for the correct diagnosis of the disease7 (Table 1).

ATS/IDSA criteria for the diagnosis of infection with nontuberculous mycobacteria.

| 1. Clinical: respiratory symptoms, provided other diagnoses have been excluded |

2. Microbiological (one is sufficient):

|

| 3. Radiological: nodular opacities or cavities on chest X-ray or chest CT scan with multifocal bronchiectasis and small nodules |

ATS/IDSA: American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America.

These criteria have to be rigorously followed to avoid unnecessary exposure to anti-NTM drugs, which are not without side effects and are expensive. The recommendations note that not all NTM infections require drug treatment, which further complicates patient management.

Two typical patterns of presentation of NTMLI have been described:

- •

The first is seen in older men who are smokers, have underlying lung disease such as COPD, or other structural lung diseases such as pneumoconiosis or a history of tuberculosis.2 The typical radiological pattern in this group of patients is cavities and fibrotic cicatricial changes in the upper lobes.3,4

- •

The second is seen in middle-aged women with no history of lung disease3,4 who, radiologically, show bronchiectasis and centrilobular nodules, particularly in the lingula and the middle lobe.4 This pattern is known as the nodular bronchiectatic form (Lady Windermere syndrome).8

We also need to be aware that immunocompromised patients, particularly AIDS patients, are more susceptible to NTMLI and, in many cases, have disseminated disease, with the only radiological finding often being the presence of necrotic-looking mediastinal lymphadenopathy.2–4,9

The aim of our study was to describe the epidemiological and radiological characteristics of patients with NTMLI in our setting and their outcomes according to the drug treatment received.

Material and methodsPatient selection. We conducted a retrospective study, reviewing the medical records of patients with at least one positive culture for NTM from January 2005 to July 2016. We studied total of 131 patients, from whom we selected those who met the ATS/IDSA diagnostic criteria and who had at least one chest computed tomography (CT) scan. We also included patients who did not meet the microbiological criteria for NTM diagnosis (only a positive sputum culture for NTM), but had symptoms and radiological findings characteristic of NTM and were therefore treated as infected.

Chest CT scans. CT scans were performed on two multidetector CT machines (Sensation 16 or Somatonplus, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). In all cases 5mm thick slices were made at 5mm intervals and in 24 cases (77% of patients included) 1mm slices were made with high resolution reconstruction algorithm at 10mm intervals. In immunosuppressed patients only, the scans were performed with iodinated contrast (80ml at a rate of 3ml/s) to better assess the presence of hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The radiological findings were evaluated by consensus by four radiologists, three of them with over 10 years of experience in thoracic radiology.

Isolation and identification of mycobacteria. Most of the samples received were from the respiratory tract (91%): 23 sputum; seven bronchoaspirate; and one bronchoalveolar lavage. The others consisted of one stool sample and two biopsies (lymphadenopathy and bone marrow).

First, an acid-fast (auramine) staining technique was performed on the direct sample, including Ziehl-Neelsen staining on respiratory samples. A culture was then performed; if it was a respiratory specimen, decontamination was performed to eliminate accompanying flora that could compete with mycobacteria and interfere with their growth. Decontamination was performed with the modified Kubica method (NaOH 2% + acetylcysteine). The culture was grown in VersaTREK liquid medium and incubated for 42 days. Finally, positive cultures were identified by Ziehl-Neelsen staining (to check positivity) and, once confirmed, molecular techniques (GenoType CM) were used, based on PCR amplification of a 16S DNA fragment and subsequent reverse hybridisation on nitrocellulose strips to generate a band profile characteristic of each mycobacterium.

Data collection. We analysed the following data for this study:

- •

Epidemiological: age, gender, smoking.

- •

Previous medical history: being positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), known cancer, COPD and immunosuppression status.

- •

Symptoms: dyspnoea, fever, cough, haemoptysis, constitutional syndrome (asthenia, anorexia, weight loss, etc.).

- •

Microbiological: NTM species isolated, history of previous tuberculosis and possible co-infection with another microorganism.

- •

Radiological: cavities, bronchiectasis, consolidations, tree-in-bud pattern, solid nodules, centrilobular nodules, ground glass, mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy, calcified lymphadenopathy, granulomas (we classified calcified nodules as granulomas) and pleural effusion.

The location of the findings in the different lung lobes (considering the lingula as an independent lobe) and the extent of lobe involvement were recorded with a grading according to the percentage of involvement of each lobe: 0 no involvement; 1 involvement of <25%; 2 involvement 25–49%; 3 involvement 50–74%; and 4 involvement ≥75%. Radiological outcome was also assessed as stability, improvement or worsening.

- •

Drug treatment received: anti-NTM, conventional antibiotics or no treatment.

Statistical analysis: statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software for Windows (v23; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The data are presented as mean±standard deviation for the quantitative variables and as frequencies and percentages for the qualitative variables. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. We considered as significant p-values of less than 0.05.

ResultsOf the 131 patients reviewed, we included in the study 34 patients who had at least one chest CT scan:

- •

31 patients who met the ATS/IDSA criteria.

- •

three patients who did not meet all ATS/IDSA criteria (only had a positive sputum culture for NTM), but had clinical and radiological findings compatible with NTM infection and were treated as infected.

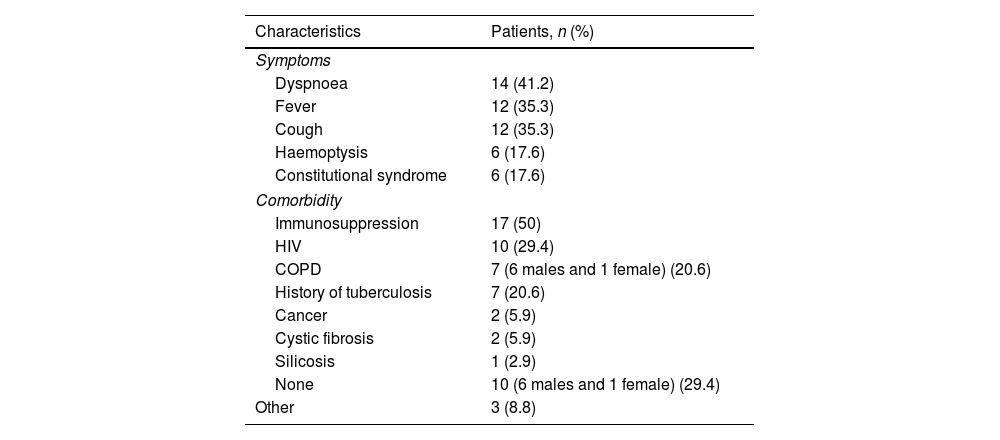

Of the 34 patients, 23 (67.6%) were male and 11 (32.4%) female. The mean age of the patients included in the study was 54.9±16.5 years. Twenty-two patients (64.7%) were smokers, 19 of whom were male and three female. The clinical characteristics and comorbidities of the patients included in the study are shown in Table 2. The most common symptoms were dyspnoea, fever and cough. Seventeen patients were immunosuppressed.

Clinical characteristics and comorbidities (n=34).

| Characteristics | Patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Symptoms | |

| Dyspnoea | 14 (41.2) |

| Fever | 12 (35.3) |

| Cough | 12 (35.3) |

| Haemoptysis | 6 (17.6) |

| Constitutional syndrome | 6 (17.6) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Immunosuppression | 17 (50) |

| HIV | 10 (29.4) |

| COPD | 7 (6 males and 1 female) (20.6) |

| History of tuberculosis | 7 (20.6) |

| Cancer | 2 (5.9) |

| Cystic fibrosis | 2 (5.9) |

| Silicosis | 1 (2.9) |

| None | 10 (6 males and 1 female) (29.4) |

| Other | 3 (8.8) |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

The right upper lobe was most frequently affected (73.5%).

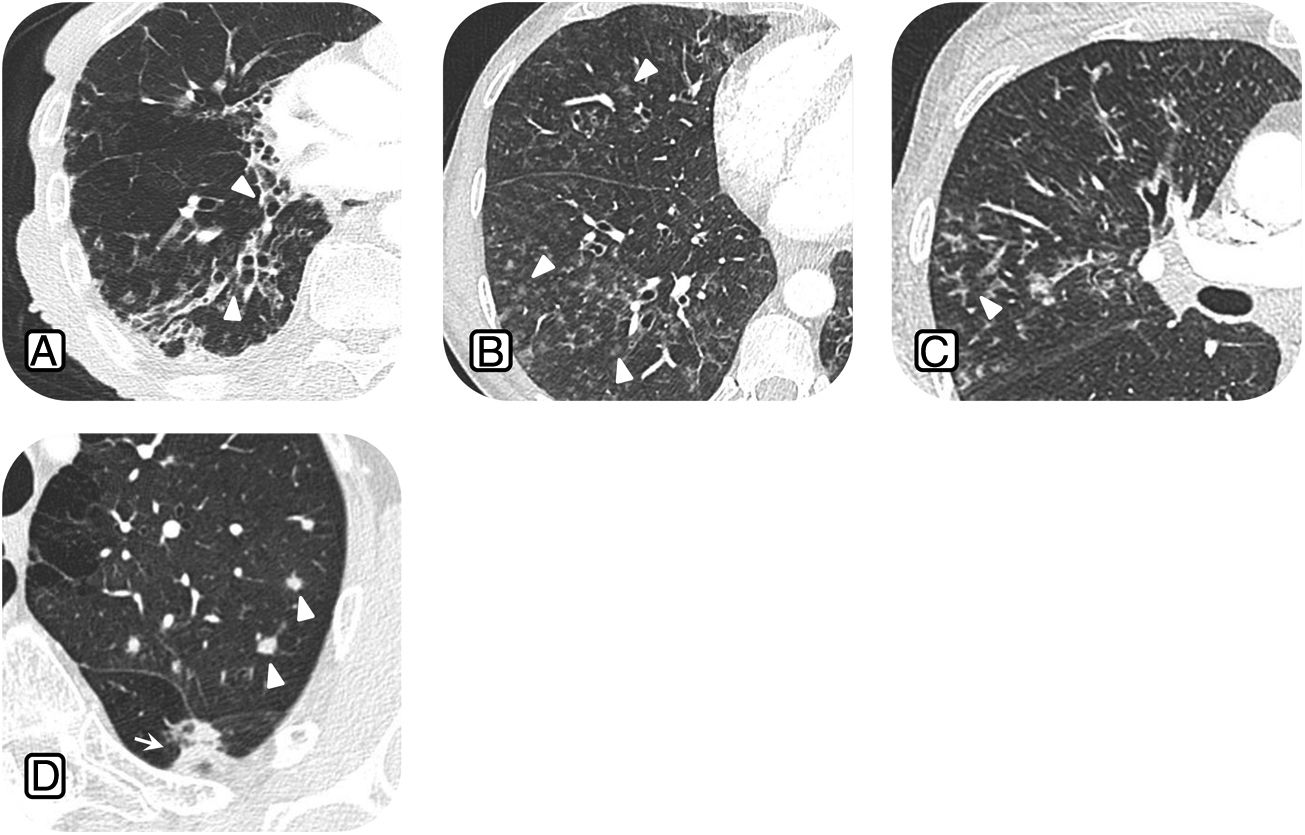

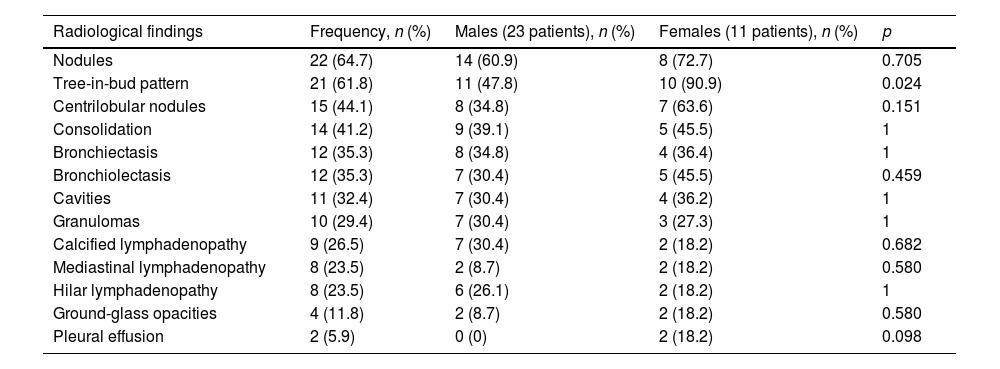

The radiological findings are shown in Table 3. The most common findings were solid nodules (64.7%), tree-in-bud pattern (61.8%), centrilobular nodules (44.1%) and consolidations (41.2%) (Fig. 1). An interesting finding was that the majority of patients who had mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy were immunocompromised HIV patients.

Overall radiological findings and comparison between males and females.

| Radiological findings | Frequency, n (%) | Males (23 patients), n (%) | Females (11 patients), n (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nodules | 22 (64.7) | 14 (60.9) | 8 (72.7) | 0.705 |

| Tree-in-bud pattern | 21 (61.8) | 11 (47.8) | 10 (90.9) | 0.024 |

| Centrilobular nodules | 15 (44.1) | 8 (34.8) | 7 (63.6) | 0.151 |

| Consolidation | 14 (41.2) | 9 (39.1) | 5 (45.5) | 1 |

| Bronchiectasis | 12 (35.3) | 8 (34.8) | 4 (36.4) | 1 |

| Bronchiolectasis | 12 (35.3) | 7 (30.4) | 5 (45.5) | 0.459 |

| Cavities | 11 (32.4) | 7 (30.4) | 4 (36.2) | 1 |

| Granulomas | 10 (29.4) | 7 (30.4) | 3 (27.3) | 1 |

| Calcified lymphadenopathy | 9 (26.5) | 7 (30.4) | 2 (18.2) | 0.682 |

| Mediastinal lymphadenopathy | 8 (23.5) | 2 (8.7) | 2 (18.2) | 0.580 |

| Hilar lymphadenopathy | 8 (23.5) | 6 (26.1) | 2 (18.2) | 1 |

| Ground-glass opacities | 4 (11.8) | 2 (8.7) | 2 (18.2) | 0.580 |

| Pleural effusion | 2 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (18.2) | 0.098 |

Common radiological findings in nontuberculous mycobacteria lung infection: A) 63-year-old patient with chronic cough and Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) lung infection. Computed tomography (CT) scan shows multiple areas of bronchiectasis (arrowheads). B) 58-year-old patient with fever, dyspnoea and Mycobacterium xenopi lung infection; CT scan shows centrilobular nodules in the middle lobe (ML) and right lower lobe (arrowheads). C) 52-year-old patient with cough and positive culture for MAC; CT scan shows tree-in-bud opacities (arrowheads) in the ML. d) 45-year-old woman with cough and Mycobacterium kansasii lung infection; CT scan shows multiple pulmonary nodules (arrowheads).

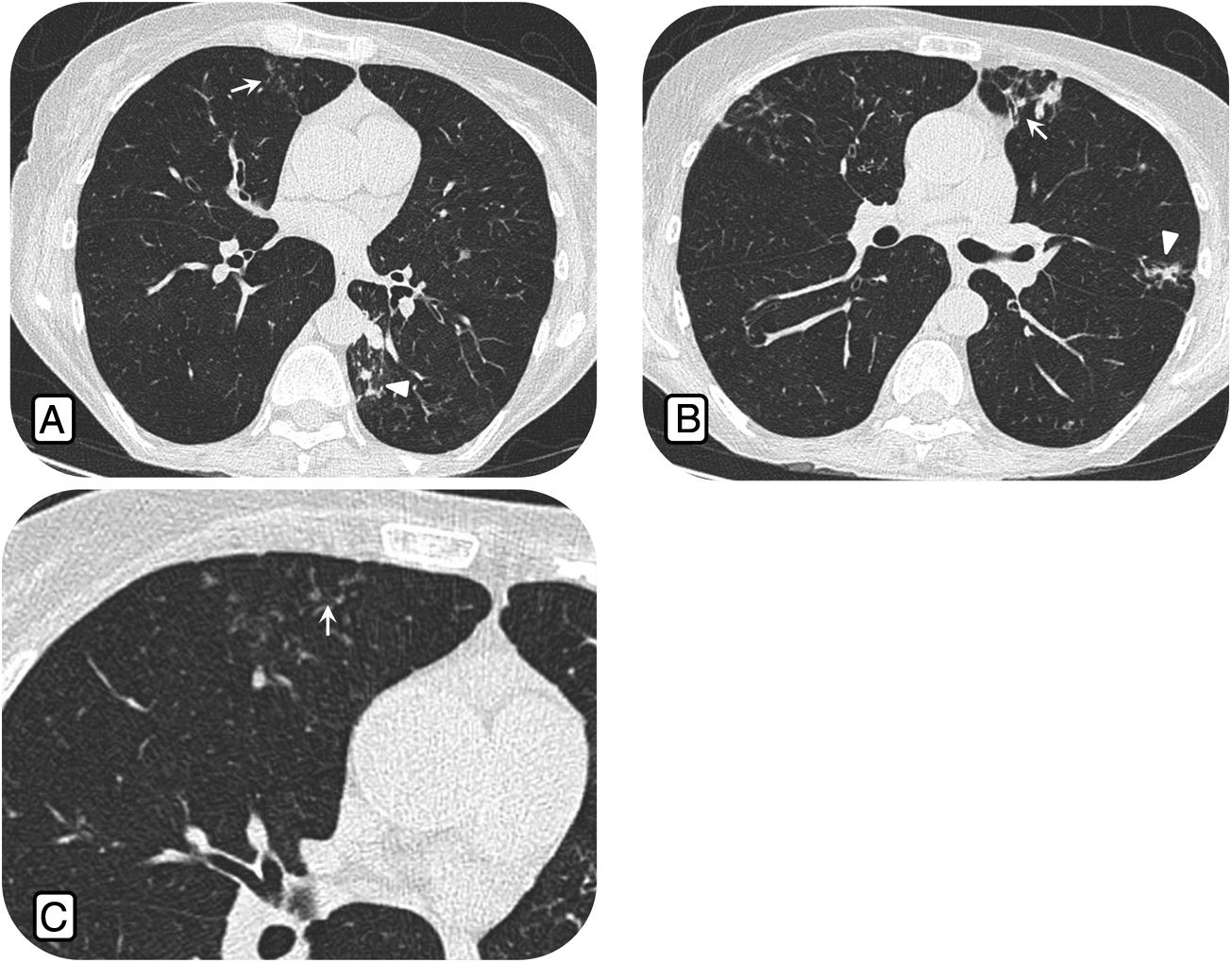

The comparative study between males and females only showed significant differences in the presence of a tree-in-bud pattern (p = 0.024), which was more common in females (Table 3). The nodular bronchiectatic form was only found in one patient (Fig. 2).

Bronchiectatic nodular form. Computed tomography study in a 67-year-old woman with chronic cough and Mycobacterium avium complex lung infection. A) Centrilobular nodules (arrow) in the middle lobe (ML) and multiple nodules in the left lower lobe (arrowheads). B) Bronchiectasis (arrow) and tree-in-bud nodules in the lingula (arrowhead). C) Centrilobular nodules (arrow) in ML.

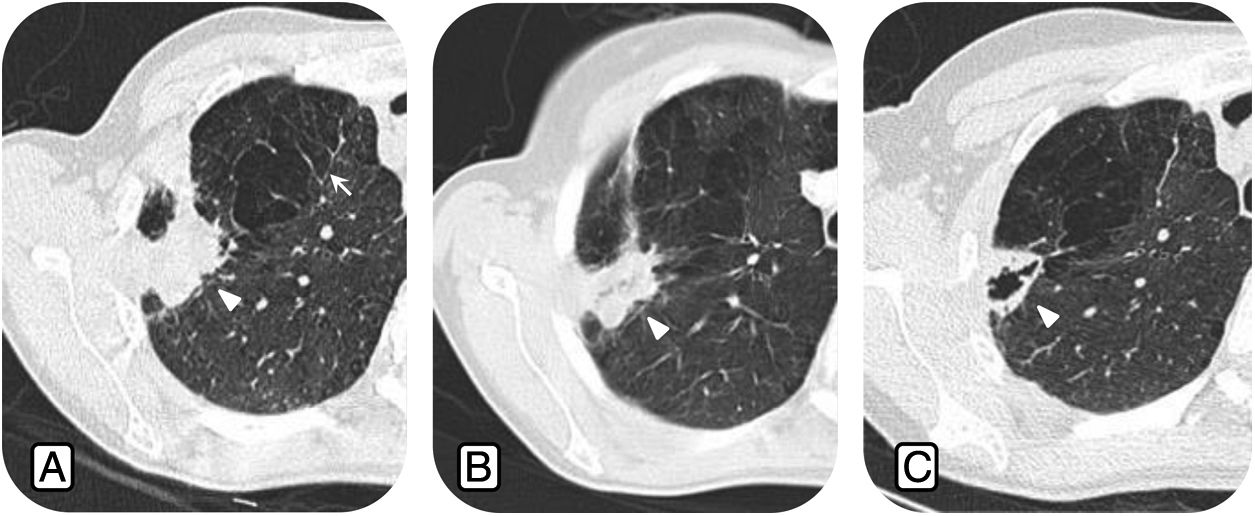

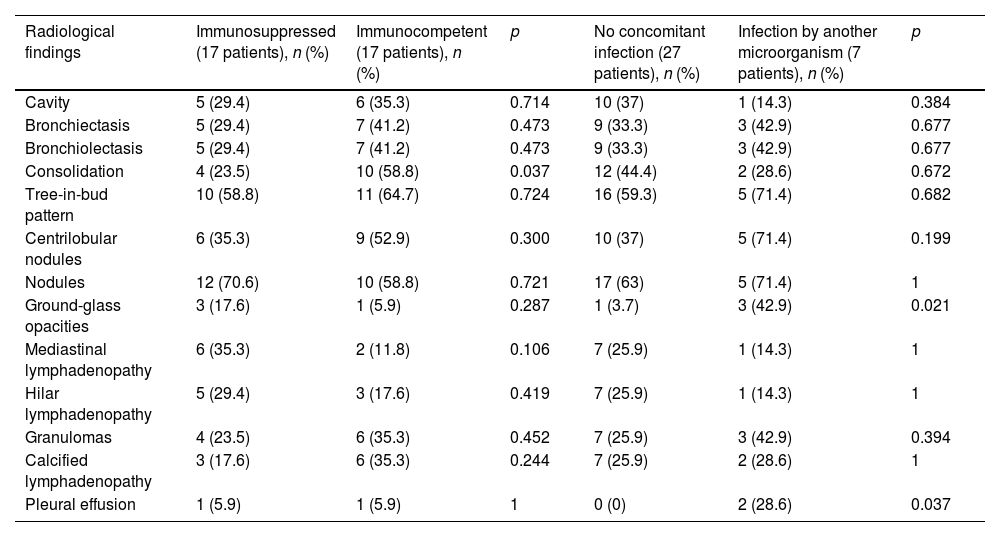

Of the immunocompromised patients, 10 were HIV positive (58.8%), three had COPD (17.6%), one had a known cancer (5.9%) and three (17.6%) had a history of other diseases (liver cirrhosis and cystic fibrosis). Compared to the immunocompetent patients, significant differences were only found in the degree of lung involvement, with greater than 75% involvement in the right upper lobe (RUL) only visible in immunocompromised patients, and in the presence of consolidations (p= 0.037), more common in immunocompetent patients (Table 4). Although not statistically significant, the presence of mediastinal lymphadenopathy was clearly more common in the immunocompromised group (Fig. 3).

Comparison of radiological findings between immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients and patients with and without superinfection by other microorganisms.

| Radiological findings | Immunosuppressed (17 patients), n (%) | Immunocompetent (17 patients), n (%) | p | No concomitant infection (27 patients), n (%) | Infection by another microorganism (7 patients), n (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cavity | 5 (29.4) | 6 (35.3) | 0.714 | 10 (37) | 1 (14.3) | 0.384 |

| Bronchiectasis | 5 (29.4) | 7 (41.2) | 0.473 | 9 (33.3) | 3 (42.9) | 0.677 |

| Bronchiolectasis | 5 (29.4) | 7 (41.2) | 0.473 | 9 (33.3) | 3 (42.9) | 0.677 |

| Consolidation | 4 (23.5) | 10 (58.8) | 0.037 | 12 (44.4) | 2 (28.6) | 0.672 |

| Tree-in-bud pattern | 10 (58.8) | 11 (64.7) | 0.724 | 16 (59.3) | 5 (71.4) | 0.682 |

| Centrilobular nodules | 6 (35.3) | 9 (52.9) | 0.300 | 10 (37) | 5 (71.4) | 0.199 |

| Nodules | 12 (70.6) | 10 (58.8) | 0.721 | 17 (63) | 5 (71.4) | 1 |

| Ground-glass opacities | 3 (17.6) | 1 (5.9) | 0.287 | 1 (3.7) | 3 (42.9) | 0.021 |

| Mediastinal lymphadenopathy | 6 (35.3) | 2 (11.8) | 0.106 | 7 (25.9) | 1 (14.3) | 1 |

| Hilar lymphadenopathy | 5 (29.4) | 3 (17.6) | 0.419 | 7 (25.9) | 1 (14.3) | 1 |

| Granulomas | 4 (23.5) | 6 (35.3) | 0.452 | 7 (25.9) | 3 (42.9) | 0.394 |

| Calcified lymphadenopathy | 3 (17.6) | 6 (35.3) | 0.244 | 7 (25.9) | 2 (28.6) | 1 |

| Pleural effusion | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.9) | 1 | 0 (0) | 2 (28.6) | 0.037 |

Nontuberculous mycobacteria lung infection in HIV-positive patients. 47-year-old man with AIDS and Mycobacterium avium complex infection. Computed tomography images show multiple subcarinal (arrowhead) and hilar (arrow) mediastinal lymphadenopathy with central hypodensity (asterisk) due to necrosis.

Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) was isolated in 18 patients (52.9%), Mycobacterium kansasii in six patients (17.6%), Mycobacterium xenopi in another six (17.6%), and in four patients (11.6%), other NTM were isolated. Seven patients (20.6%) were also infected by another microorganism, the most common (4 patients) being Haemophilus influenzae. Table 4 shows the different radiological findings according to the presence or absence of co-infection; statistically significant differences were only found for ground glass (p 0.021) and pleural effusion (p 0.037) which were virtually only found in cases of co-infection. Although no significant differences were found, the percentages of patients with a tree-in-bud pattern, centrilobular nodules and solid nodules were clearly higher in patients with co-infection.

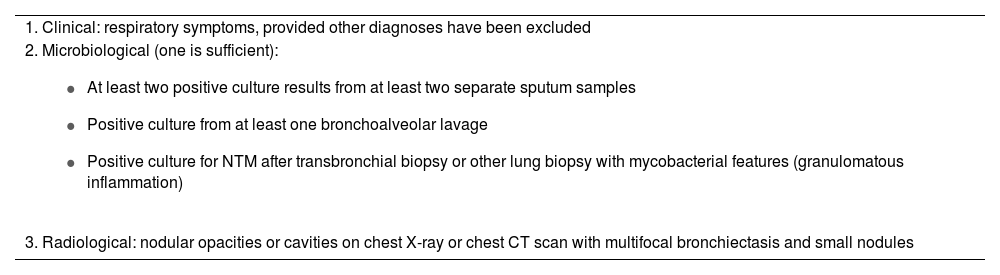

In terms of drug treatment, 23 patients (67.6%) were treated with antituberculosis drugs, seven (20.6%) received conventional antibiotics, two (5.9%) both treatments and two others (5.9%) were not treated. Most of the patients treated with antituberculosis drugs (18 out of 25; 72%) showed radiological improvement (Fig. 4), except for two patients (one showed worsening radiologically and the other's images showed stable disease). Five of the 18 patients treated with antituberculosis drugs were not followed up radiologically. Of the seven patients treated exclusively with conventional antibiotics (five of whom were also infected by another microorganism), all were found to have improved except one, who was lost to follow-up.

Radiological changes related to the infection after drug treatment. A) Axial CT images show consolidation in the right upper lobe (RUL) (arrowhead) and emphysema in the RUL (arrow). B) Same patient two months after starting anti-NTM treatment. We can see a decrease in the size of the consolidation (arrowhead). C) Nine months after anti-NTM treatment, there is a decrease in consolidation, the image now showing an area of central cavitation (arrowhead).

In our study, out of 131 patients with NTM-positive samples, only 34 were included, corroborating the great difficulty in making an accurate diagnosis of NTMLI, as in most cases a positive culture for NTM indicates colonisation and not infection. The microbiological criteria for the diagnosis of NTM have varied over the years and remain subject to debate. Some authors report that NTM colonisation can develop into an actual infection in the long term, so the ATS/IDSA guidelines recommend repeat testing until the diagnosis is confirmed or ruled out (evidence of another diagnosis to explain the symptoms).7

In our study, seven patients were infected by another microorganism, with H. influenzae being the most common. Previous studies indicate that patients with NTMLI are frequently chronically infected with other microorganisms.10,11 One study assessed changes in lung consolidation in patients with NTMLI when treated with antibiotics alone (not anti-NTM) and found that in 88% of cases the consolidation disappeared completely with the antibiotics,12 concluding that consolidation in patients with NTMLI was rarely due to invasion of the lung parenchyma by NTM, but rather to the presence of other microorganisms. Detection of consolidation during follow-up of these patients should not therefore be viewed as disease progression, and conservative treatment or empirical antibiotic therapy should be considered before starting anti-NTM therapy. In our series, most of the patients who were infected by another organism improved with conventional antibiotic therapy, suggesting that these patients probably did not have actual NTM infection, but rather their symptoms were due to the concomitant organism.

In line with articles in the literature, in our study, the most common type of NTM isolated was MAC. There has been little study of radiological differences between different NTM species, because the population sample is not usually large enough for a comparative study. However, other studies with a larger population sample report that bronchiectasis and nodules are significantly more common in patients with MAC infection than in other NTM,11,13,14 while cavities are more common in patients with M. kansasii infection.15 In our case, we found no significant differences between the different NTM species.

In our study, the majority of patients with NTMLI were middle-aged male smokers with dyspnoea. In terms of comorbidities, HIV infection (29.4%) was the most common, followed by a history of COPD (20.6%).

Diseases associated with structural lung damage are clear predisposing factors for NTMLI, with COPD being the most common. There are other disorders such as pneumoconiosis which have classically been associated with NTMLI, but nowadays their importance is relative as they are decreasing in prevalence worldwide.6 In our case, one of the patients had lung disease due to silicosis.

Although the evidence is limited, some studies suggest that smoking may be a cofactor in the development of NTMLI.6,16,17 In our study, 64.7% of the infected patients were smokers (82.6% of the males included).

Cystic fibrosis has also been linked to both NTM colonisation and NTMLI.7 This is even more relevant today as the life expectancy of these patients is increasing.6,18 NTM have been isolated in 4-32% of respiratory samples from patients with cystic fibrosis.6,19 In our series, two patients had cystic fibrosis and both were infected by another microorganism.

Lung damage due to concurrent or previous Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection has also been associated with NTMLI. NTM are frequently isolated from respiratory samples of patients with TB, but their clinical relevance is still unclear. In our case, 20.6% of patients with NTMLI had a history of tuberculosis.

Immunosuppressed patients have an increased risk of NTMLI. Immunosuppressive conditions associated with NTMLI include HIV infection, haematological or lymphoproliferative malignancies, stem cell and solid organ transplantation, and inflammatory disorders treated with biological drugs.2,6,9,20 Inhaled corticosteroids have also been suggested to increase the risk of NTMLI among patients with chronic respiratory diseases (asthma and COPD).6,9,21 It should be noted that NTM isolation in people with HIV is common and is most often not associated with disease. A study in South-East Asia showed that out of 1060 people infected with HIV, NTM was isolated in respiratory specimens in 21% and of these, only 19 (2%) had NTMLI.22

NTMLI in patients without predisposing risk factors is described in non-smoking, thin middle-aged women with bronchiectasis, this set of factors classically being included in the nodular bronchiectatic form.8 One study showed that 36% of these patients had mutations for the gene encoding the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulation (CFTR) protein,6,7,23,24 and recent data indicate that these patients have a higher prevalence of mutations in genes controlling ciliary function, connective tissue, immune function and CFTR compared to the control population, suggesting that a combination of these mutations in conjunction with environmental factors may be strongly associated with NTMLI in "healthy" individuals.1,6,24

Two radiological patterns have been described in NTMLI: cavitary disease (classic) and nodular bronchiectatic disease (non-classic).

The classic pattern is similar to pulmonary M. tuberculosis infection, more common in older men with COPD. Radiological findings include upper lobe cavities, nodules and fibrotic cicatricial changes,2,4,5 which are indistinguishable from those produced by tuberculous infection.25 NTMLI progresses even more slowly than TB and compared to TB, NTMLI is more indolent; it can remain stable both clinically and radiologically for years, although without adequate treatment it does tend to progress and can be fatal.3,26 In our case, the most common radiological findings in COPD patients were nodules, centrilobular nodules, granulomas, calcified lymphadenopathy and bronchiolectasis; cavities were observed in almost 30% of cases.

The non-classic pattern has been described in middle-aged women without predisposing risk factors.2 This is the nodular bronchiectatic form. Radiological findings include centrilobular nodules and tree-in-bud pattern associated with cylindrical bronchiectasis usually in the same lobe, with the middle lobe and lingula being the most frequently affected.2,4,5 Other occasional findings include consolidation and ground glass opacities. In our study, although females predominantly had a tree-in-bud pattern (p = 0.024) and centrilobular nodules (not statistically significant but found in 63.6% of cases compared to 34.8% in males), only one patient had the radiological pattern characteristic of the nodular bronchiectatic form. However, in our clinical practice we find patients with radiological findings suggestive of Lady Windermere syndrome who are never diagnosed with NTMLI (in our database, out of 11 patients with this pattern the diagnosis was only confirmed in one case). Patients with nodular bronchiectatic NTMLI have been reported to have a higher number of false negative sputum cultures and many of them require bronchoscopy or biopsy for diagnosis. Therefore, in situations where there is a high clinical and radiological suspicion of NTMLI and sputum cultures are negative, bronchoscopy is indicated.14 However, considering that bronchoscopies and biopsies are invasive and expensive, the patient's symptoms remain a determining factor in decision-making.13 This could explain why in our study only one of our patients with confirmed NTMLI had the characteristic pattern of the nodular bronchiectatic form; as these were patients with few respiratory symptoms and, as at times diagnosis and treatment can cause more adverse effects than benefits, such patients are often not investigated and a definitive diagnosis is never made.

Immunosuppressed patients with HIV infection are often found to have disseminated NTM disease. Infection usually occurs in patients with CD4 count <50,9 with the gastrointestinal tract being the source of infection and dissemination occurring as a result of bacteraemia.4,5,7,9 Radiologically, it is important to note that NTMLI usually coexists with other lung infections or cancers (Kaposi's sarcoma), so the radiological findings are difficult to establish.5 However, different studies have reported that the most common findings tend to be mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy.4 Other findings can include miliary nodules, reticular opacities, cavities and fibrotic cicatricial changes.4,5,27 In our study, none of the patients with HIV had disseminated disease. However, this group were more likely to have mediastinal (p=0.001) and hilar (p=0.019) lymphadenopathy; another statistically significant radiological finding in this group of patients was ground-glass opacities (p= 0.033). Meanwhile, bronchiectasiss (p=0.046), bronchiolectasis (p=0.046) and granulomas (p=0.015) were less common than in patients without HIV infection.

Diagnosis of a patient with NTMLI does not mean they have to be started on drug treatment immediately. The decision to treat or not to treat should be based on the patient's symptoms and the potential risks and benefits of a long course of multiple antibiotics.2,7,28 Generally, patients with fibrocavitary disease require immediate treatment because infection is associated with a higher mortality rate.1 However, in bronchiectasis, symptoms are milder and patients do not generally have comorbidity, so treatment is not always advisable due to the significant associated adverse effects.7,28

The optimal treatment regimen has yet to be established. However, therapy should include at least three antituberculosis drugs for one year followed by confirmation of negative cultures (the treatment should be continued until the patient has negative cultures after one year of therapy).7

Most of the patients treated with antituberculosis drugs (18 out of 25) improved. Patients treated with antibiotics alone also improved (one of them was lost to follow-up), so in these patients the radiological findings were probably associated with the concomitant microorganism.

Our study has several limitations; it is a retrospective study with a small sample of patients. As we virtually only included patients meeting ATS/IDS criteria, infected patients with insufficient microbiological cultures were probably omitted.

ConclusionsDiagnosis of NTMLI is complex. Radiological findings are non-specific and overlap with those of tuberculosis or other infections. Therefore, in the presence of clinical signs suggestive of insidious lung infection and imaging showing cavities or bronchiectasis associated with nodules or opacities in a tree-in-bud pattern, NTM should be included in the differential diagnoses.

A significant percentage of patients with apparent NTMLI may have superinfection with other microorganisms and these may often be responsible for the radiological and clinical findings.

AuthorshipResponsible for the integrity of the study: CCR and ECG.

Article conception: CCR and ECG.

Article design: CCR, ECG, MAM and XGC.

Data collection: CCR, ECG, ÓCL, MGD, MAM and AGL.

Data analysis and interpretation: CCR, ECG, MAM, XGC and MGD.

Statistical processing: JCOM and CCR.

Literature search: CCR and ECG.

Drafting of the article: CCR and ECG.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: MAM, XGC, ÓCL, MGD, CCR, ECG and AGL.

Approval of the final version: CCR, ECG, MAM, XGC, MGD, ÓCL and AGL.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The author acknowledges the assistance of Joan Carles Oliva Morera, from the Statistics Department of the Consorci Sanitari Parc Taulí [Parc Taulí Health Consortium], in the analysis of statistical data.