Suplement “Update and good practice in the contrast media uses”

More infoThe use of hepatobiliary-specific contrast agents in liver MRI is a crucial diagnostic tool for evaluating liver disease, enabling the detection and characterisation of focal lesions and vascular alterations, as well as the assessment and grading of chronic hepatopathy. Paramagnetic hepatobiliary-specific contrast agents are gadolinium-based, partially taken up by hepatocytes, and excreted via both renal and biliary pathways. There are two linear ionic molecules that are currently commercially available: gadobenic acid (Gd-BOPTA) and gadoxetic acid (Gd-EOB-DTPA). Their main clinical indications include distinguishing and characterising focal liver lesions on healthy liver tissue, diagnosing and staging hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatopathy, and increasing reliability in the detection of hepatic metastases in oncology patients, especially prior to surgery. They are also useful in the evaluation of the biliary tract and in assessing complications of hepatic surgery such as bile leaks.

La resonancia magnética hepática con medios de contraste hepatoespecíficos es una herramienta diagnóstica crucial para evaluar las enfermedades hepáticas. Permite la detección y la caracterización de lesiones focales y alteraciones vasculares hepáticas, así como laevaluación y gradación de la hepatopatía crónica. Los contrastes hepatoespecíficos paramagnéticos están basados en el gadolinio, se incorporan parcialmente a los hepatocitos, y se excretan tanto por la vía renal como por la biliar. Actualmente se dispone comercialmente de dos moléculas lineales iónicas: el ácido gadobénico (Gd-BOPTA) y el ácido gadoxético (Gd-EOB-DTPA). Sus principales indicaciones clínicas incluyen diferenciar y caracterizar lesiones focales hepáticas sobre hígado sano, diagnosticar y estadificar el carcinoma hepatocelular en pacientes con hepatopatía crónica, e incrementar la fiabilidad en la detección de metástasis hepáticas en pacientes oncológicos, especialmente antes de la cirugía. También son útiles en la evaluación anatómica de la vía biliar y las complicaciones de la cirugía hepática como la fuga biliar.

Liver Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) with intravenous contrast is an indispensable diagnostic tool for the evaluation of liver diseases, and allows for improved detection and characterisation of focal lesions and hepatic vascular abnormalities in patients with incidental lesions, chronic hepatopathy, vascular disorders or cancer.

Contrast media are administered intravenously and can generally be classified by their mechanism of action (paramagnetic or superparamagnetic) or by their distribution in the body after administration. The contrast media currently used are paramagnetic and gadolinium based. In the study of the liver, both extracellular and hepatobiliary contrasts can be used.1

Extracellular contrast media are the most commonly used in MRI studies. After intravenous administration, they are initially distributed in the vascular compartment and progressively diffuse into the extravascular and extracellular interstitial space, without being incorporated into the interior of the cells. From this space they return to the vessels for renal excretion. In the liver, these contrasts may have a prolonged distribution phase in areas with increased vascular space, such as in haemangiomas, or with increased extracellular space with affinity for the contrast, such as in fibrosis. There are several extracellular contrast media on the market, with differences based on their molecular structure, their physical/chemical characteristics and their pharmacokinetic properties.2 The contrast agents in use have a macrocyclic structure and are extremely safe, even in patients with impaired renal function.3 They are typically administered as a rapid intravenous bolus, at a dose of 0.1 mmol/kg (equivalent to 0.2 ml/kg at the usual concentration of 0.5 mmol/ml), followed by a push bolus of normal saline solution at the same rate.2,4

Hepatobiliary contrast agents were historically developed as gadolinium- and manganese-based paramagnetic contrast agents or as iron-based superparamagnetic contrast agents. Nowadays, only gadolinium-based paramagnetic contrast agents are used.1 Hepatobiliary paramagnetic contrast agents using gadolinium partially incorporate in the hepatocyte. It is excreted both through the kidneys and the bile ducts. The partial incorporation of contrast into the hepatocyte and its excretion through the bile canaliculus is what enables a highly reliable evaluation of the hepatic parenchyma and characterisation of its anatomy, focal lesions and alterations in the vascular and biliary tree.5 This review will discuss the properties and characteristics of hepatobiliary gadolinium contrast agents in MRI, their clinical indications, and the criteria for radiological interpretation of the main findings.

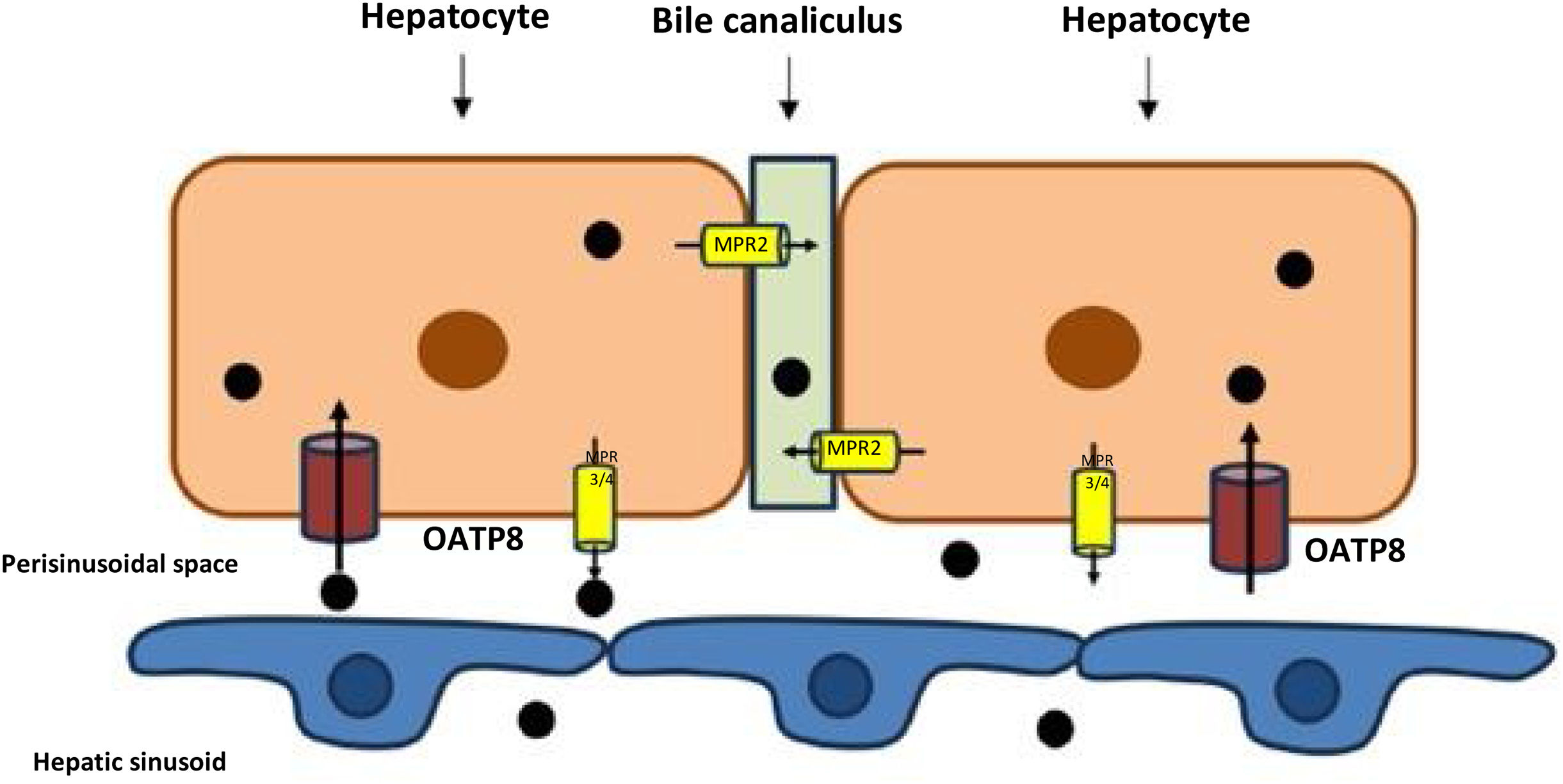

Types of hepatobiliary contrast agents used in liver studies with magnetic resonance imagingHepatobiliary contrast media are incorporated into hepatocytes through an active transport mechanism by membrane proteins. Once inside the hepatocyte, they can return to the sinusoidal vascular space or be excreted into the bile canaliculus. This movement marks the different visualisation phases in the vessels, the liver parenchyma and the biliary tree. The uptake by hepatocytes occurs through the organic anion transporting polypeptide (OATP1) group of transporters, particularly the OATP1B1/B3 (also called OATP8) located in the sinusoidal membrane of the hepatocyte. From inside the hepatocyte (Fig. 1), part of this intracellular contrast is excreted into the bile through the multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2) transporter located in the canalicular membrane.6,7 Another part of the contrast returns to the vascular space through the sinusoidal multidrug resistance-associated protein transporter 3/4 (MRP3/MRP4). Clearance towards the sinusoid depends on the portal flow.8 Liver lesions whose cellularity has lost the expression of these transporters and lesions whose origin is not hepatocellular will not incorporate this contrast into their cells.

Diagram of the transport and accumulation of hepatobiliary contrast inside the hepatocyte. There is active uptake from the sinusoidal membrane through the OATP8 transporter (=OATP1 B1/B3) and excretion into the bile canaliculus through the MPR2 channel. Part of the intracellular contrast may return to the vascular space via the sinusoidal transporter MRP3/MRP4.

There are currently two hepatobiliary contrast agents available for clinical use in Europe. Both contrasts are administered intravenously, are gadolinium-based, and undergo partial hepatic uptake and excretion, which allows images to be obtained in the phase in which the contrast is predominantly inside the hepatocyte, called the hepatobiliary phase (HBP). These contrasts are gadobenic acid (Multihance®, Braco, Italy) and gadoxetic acid (Primovist/Eovist®, Bayer-Schering Pharma, Germany). In this paper, the names Gd-BOPTA and Gd-EOB-DTPA are used for these contrasts, given their greater familiarity in radiological language.

Structurally, both Gd-BOPTA and Gd-EOB-DTPA are ionic linear molecules with the ability to bind to plasma proteins. In the case of Gd-BOPTA, the formulation has a concentration of 0.5 mmol/ml, with a usual dose of 0.1 ml/kg body weight. The approved dose of Gd-EOB-DTPA is 0.1 ml/kg body weight, although its concentration is lower, at 0.25 mmol/ml.

The hepatic excretion of Gd-BOPTA is approximately 4% of the administered dose. For HBP imaging, images should be acquired at 90−120 min. to maximise uptake by the liver parenchyma. This contrast enables a dynamic study with the early and late arterial, portal and equilibrium phases between the vascular and interstitial compartments, all of which are separated from the HBP, which comes much later. The biliary excretion of Gd-EOB-DTPA is approximately 50%, which makes it possible to obtain images in the HBP starting 20 min. after intravenous administration. Gd-EOB-DTPA also enables a complete dynamic study with the early arterial phase, late arterial phase and portal phase. The transition phase represents a mixture of contrast in the interstitium and in the hepatocyte, so it differs from the traditional equilibrium phase presented by the other contrasts. A summary of the main physical/chemical characteristics of both compounds, Gd-BOPTA and Gd-EOB-DTPA, is shown in Table 1. In this paper, protocols for the acquisition of dynamic sequences after contrast administration are defined with a contrast injection speed of 2 ml/s and a weight-adjusted volume (0.1 ml/kg), as instructed in the package leaflet.

Main physical/chemical characteristics of the two hepatobiliary contrast agents marketed in Europe: Gd-BOPTA and Gd-EOB-DTPA.

| Gd-BOPTA | Gd-EOB-DTPA | |

|---|---|---|

| Trade name | Multihance® | Primovist/Eovist® |

| Excess liganda | 0% | 0.5% |

| Osmolality (mOsm/kg H2O, 37 °C) | 1970 | 688 |

| Viscosity (mPa s, 37 °C) | 5.3 | 1.2 |

| Thermodynamic stability constant (Log Ktherm) | 22.6 | 23.5 |

| Conditional stability constant (Log Kcond) | 18.4 | 18.7 |

| T1/2 | <5 s | <5 s |

| Relaxation (r1/r2, 1.5 T)b | 6.0−6.6/7.8−9.6 | 6.5−7.3/7.8−9.6 |

| Relaxation (r1/r2, 3.0 T)b | 5.2−5.8/10.0−12.0 | 5.9−6.5/10.0−12.0 |

| Elimination | 96% kidney | 50% kidney |

| 4% liver | 50% liver |

Following administration of the contrast medium, MRI images are acquired at a time interval determined by the main compartment, where there is a higher concentration of the injected compound. Given the differences in the dynamic behaviour of hepatobiliary contrasts, the naming of some of the phases after administration depends on the contrast used.

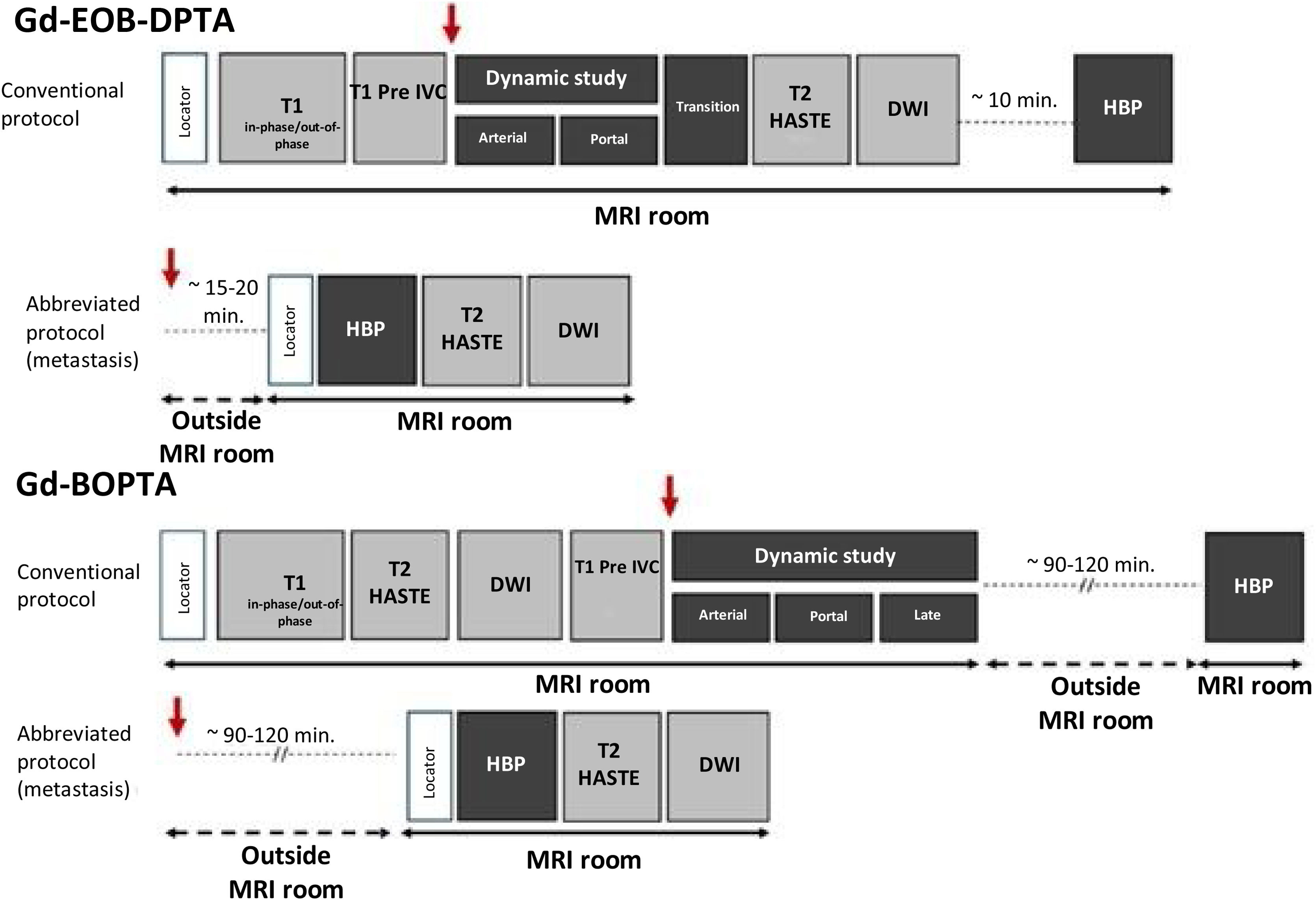

Most of the parameters used in the acquisition protocols for liver MRI with hepatobiliary contrast agents are similar to those used for extracellular contrast agents, except for the images obtained in HBP, the delay of which will, as mentioned, depend on the specific type of contrast agent used. Sometimes it may only be necessary to acquire HBP in what we know as abbreviated protocols for the presurgical detection of liver metastases, especially in patients with colorectal cancer.10 A summary of the usual protocols used with hepatobiliary contrasts is shown in Fig. 2. The main sequence for the pre-contrast, dynamic and HBP study is based on a 3D gradient echo with very short TR/TE times, a flip angle between 13 and 30°, and usually with fat suppression to maximise the intensity of the contrast signal.

Standard liver MRI protocols for hepatobiliary contrasts. A conventional protocol and an abbreviated protocol that can be used in the detection of liver metastases are shown, in both cases injecting the contrast outside the MRI equipment and waiting 15–20 min. with Gd-EOB-DPTA and 90–120 min. with Gd-BOPTA. In all cases, the red arrow indicates intravenous injection of contrast. DWI: diffusion-weighted image; HBP: hepatobiliary phase.

At this stage, the hepatic artery and its branches show complete enhancement while the contrast has not yet reached the suprahepatic veins. ACR-LI-RADS11 definition distinguishes two arterial phases: 1) the early arterial phase, in which the portal vein is not opacified; and 2) the late arterial phase, in which opacification is already present in the portal vein, but not in the suprahepatic veins.

The time we must wait between the start of the injection of contrast into an upper limb peripheral vein and the acquisition of the images is a very important parameter. In general, it is preferred to acquire the early arterial phase once the contrast is detected in the abdominal aorta in studies with bolus tracking. The region of interest (ROI) to identify the arrival of the contrast bolus should be located at the centre of the vessel, usually in the abdominal aorta near the start of the coeliac trunk. For the highest quality arterial study in dynamic acquisition, a 25-ml saline push bolus is used immediately after completing the contrast injection and at the same speed.

Usually two arterial phases are acquired, one early and one late. The early arterial phase is acquired approximately 5 s. after detecting the arrival of contrast to the aorta (this is the time required to cancel the bolus tracing sequence and start the acquisition). If this sequence is not available, the early arterial phase could be obtained about 15 s. after injection, although the quality of the arterial phase will not be guaranteed. In the case of the late arterial phase, this is acquired at approximately 20 s. in studies with bolus detection, or approximately 30−35 s. after peripheral venous administration.

The late arterial phase is critical to having the best detection and characterisation of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC),12 so obtaining diagnostic-quality images during this phase is critical. For this reason, liver imaging protocols are currently performed with multiple acquisitions during the arterial phase, which minimises study variability. These multiple arterial acquisitions minimise the problems associated with self-limiting transient dyspnoea that can occur during arterial phase acquisition after Gd-EOB-DTPA administration, which causes motion artifacts, limiting the quality of the acquisition. A recent meta-analysis13 found a 13% incidence of severe transient artifacts in single arterial acquisition, compared to 3% in multiphase acquisitions, with a statistically significant difference. A significant difference was also found in the incidence of these transient artifacts between studies performed with Western populations (Europe and the USA, 16%) and Eastern populations (Asia-Pacific, 9%).13 Age over 65 years, a body mass index ≥25 kg/m2, having chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the existence of moderate or severe pleural effusion are independent risk factors for the appearance of these artifacts in arterial acquisition after the administration of Gd-EOB-DPTA.14

Portal phase or portal venous phaseThe image series acquired in the portal phase is obtained approximately 60 s. after the administration of intravenous contrast in the upper limb or approximately 50 s. after the trigger threshold in studies with bolus tracking. During this phase, there is maximum enhancement of the liver parenchyma, and both the portal vein and the suprahepatic veins are completely opacified. These images allow assessment of the presence of tumour washout in patients with HCC, regardless of the contrast medium. It is also the phase of the dynamic study with the highest diagnostic yield in the detection of liver metastases.

Late or equilibrium phaseThis series is obtained approximately 3 min. after administration of extracellular contrast and Gd-BOPTA. In this phase the portal vein and suprahepatic veins are opacified, but less so than in the portal venous phase. Enhancement of the liver parenchyma is also observed, but in a lower intensity than during the portal phase. In studies performed with extracellular media or with Gd-BOPTA, the presence of washout can be determined during this phase according to LI-RADS criteria in patients with chronic liver disease.

This phase does not exist if Gd-EOB-DPTA is used as a contrast.

Transition phaseThis phase is obtained in studies with Gd-EOB-DPTA, as this contrast is incorporated early into the hepatocytes and there is no pure extracellular phase beyond the portal phase. This phase is not considered in studies performed with Gd-BOPTA. In general, it is obtained between 2 and 5 min. after administration of the contrast, where there is a transition with contrast extending to both extracellular and intracellular compartments. In this phase, the vessels and liver parenchyma have similar signal intensity. For the characterisation of focal lesions in patients with chronic liver disease, the presence of hypointensity during this transition phase is not considered washout in most international guidelines, with the exception of the KLCA-NCC guideline from South Korea.15,16

Hepatobiliary phaseThe delay in obtaining HBP depends on the contrast medium used. With Gd-EOB-DPTA, a quality HBP can be obtained as early as 15−20 min. after intravenous administration. In some centres, DWI and T2-WI sequences are performed after the dynamic study to optimise the protocol and reduce the study acquisition time.17

Studies using Gd-BOPTA require a longer waiting time to obtain the HBP, between 90−120 min. In these cases, the patient usually waits outside the MRI room for its acquisition. This adds time to the study, although the acquisition of the second part is rapid and hardly upsets the timing of appointments when controlled.

The HBP is considered to be of adequate quality when the liver parenchyma clearly shows hyperintensity compared to the blood vessels. The presence of contrast excreted into the biliary tract does not equate to maximum enhancement of the liver parenchyma, and by itself does not imply a quality HBP.11,12,18

In patients with liver disease, due to the loss of functionality of hepatocyte membrane transporters, it is common to observe decreased parenchymal enhancement in this HBP, as well as a slower realisation of maximum liver enhancement. Furthermore, a heterogeneous enhancement pattern may be observed in this situation if there is significant liver fibrosis or sinusoidal perfusion disturbance. A pattern of reduced uptake with periportal distribution has also been described in other chronic liver diseases, especially in primary biliary cirrhosis and idiopathic portal hypertension.18

Some studies have used this enhancement of the liver parenchyma to make a qualitative and quantitative determination of liver function, which may be useful in long-term follow-up and monitoring after treatment.19 For example, relative liver enhancement is directly related to the likelihood of one-year survival in liver transplant patients.20

Clinical indicationsMost focal liver lesions do not have normal and functioning hepatocytes and will not show uptake of hepatobiliary contrast media, so most lesions appear hypointense in HBP.

Some lesions show contrast media uptake through OATP8 transporters, which is a valuable feature for the characterisation of focal lesions. Table 2 shows a summary of the behaviour of the main lesions usually evaluated using hepatobiliary contrast media in different clinical contexts.

Classification of the main types of focal liver lesions based on the clinical context and their usual behaviour in the hepatobiliary phase.

| Clinical context | Type of lesion | Typical behaviour during HBP | Additional comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-cirrhotic patients | Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) | Iso/hyperintense in 97% | Benign lesion that rarely requires surgical treatment. |

| Some lesions may display a hyperintense peripheral ring | |||

| Hepatocellular adenoma (HCA) | Hypointensity: | Benign hepatocellular neoplasia with different molecular subtypes. Different risk of bleeding and malignant transformation depending on the subtype. | |

| 100% of HNF-1α-inactivated HCA | |||

| Iso/hyperintensity: 59% of β-catenin-mutated; | |||

| 14% of inflammatory HCA; 11% of unclassified HCA | |||

| Patients with cirrhosis | Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | Hypointensity: usual behaviour, majority of HCC | Normal enhancement behaviour in the arterial phase and washout during the portal or equilibrium phase (Gd-BOPTA). Transition phase (2−5 min) obtained with GD-EOB-DPTA not valid for washout detection, except in South Korean guidelines. |

| Iso/hyperintensity: 8.8−14.4% of HCC | |||

| Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | Typically hypointense, although the centre may show hyperintensity due to contrast accumulation. | EOB-cloud phenomenon less common than on healthy liver. | |

| Regeneration nodules | Typically isointense to the rest of the parenchyma | ||

| Dysplastic nodules | Up to 30% hypointense; the rest iso/hyperintense | ||

| Cirrhotic doughnut nodules | Doughnut-shaped with peripheral hyperintense ring enhancement | They do not show enhancement in the arterial phase. | |

| Cancer patients | Liver metastases | Hypointensity: | HBP also useful for detection of metastasis of neuroendocrine tumours. |

| Common behaviour in most liver metastases | |||

| Iso/hyperintensity: | |||

| Retention of contrast material in the central area | |||

| FNH-type lesion | Typically hyperintense or isointense. | Patients treated with oxaliplatin-containing chemotherapy regimens. | |

| Occasionally hypointense with a hyperintense ring | |||

| Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | Hyperintense central zone with hypointense peripheral ring (EOB-cloud phenomenon) | ||

| Vascular abnormalities | FNH-type lesion (Budd-Chiari) | Typically hyperintense or isointense. | Usually hyperintense in T1 and hypointense in T2 compared to the rest of the parenchyma. |

| FNH-type lesion (Fontan) | Typically hyperintense or isointense. | Occasionally they may show washout during the portal phase. |

HBP: hepatobiliary phase.

The main indications in this section are related to the characterisation of hepatocellular tumours.

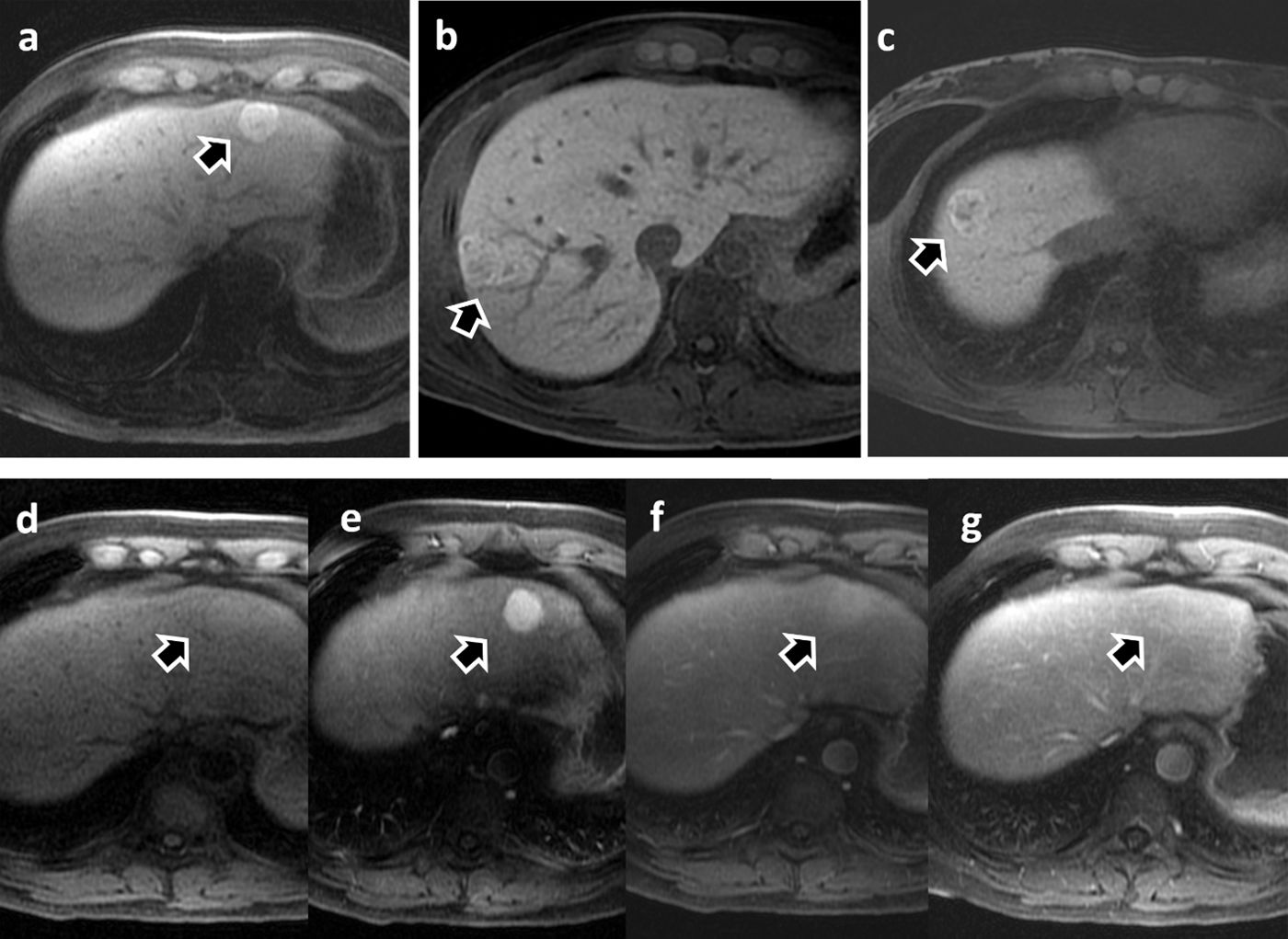

Focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular adenomaDifferentiation between focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) and hepatocellular adenoma (HCA) is one of the main indications in routine clinical practice for performing MRI studies and obtaining images in HBP. Both entities present similar characteristics in conventional imaging studies and it can be difficult to differentiate between them (Figs. 3 and 4). Establishing the distinction is important, as FNH is a benign disorder that rarely requires treatment, while HCA is a benign tumour which carries a risk of bleeding and malignant transformation, which may require surgical treatment. Furthermore, HCA are not homogeneous and there are different pathological subtypes with different behaviour and prognosis. The most recent version of the molecular and gene expression classification of HCA, published in 2017, classifies them into eight subtypes.21 However, most groups and publications consider four main subtypes: HFN1α-inactivated adenoma (HFN1α; hepatocyte nuclear factor 1α); inflammatory adenoma; β-catenin mutated adenoma; and unclassified adenoma.

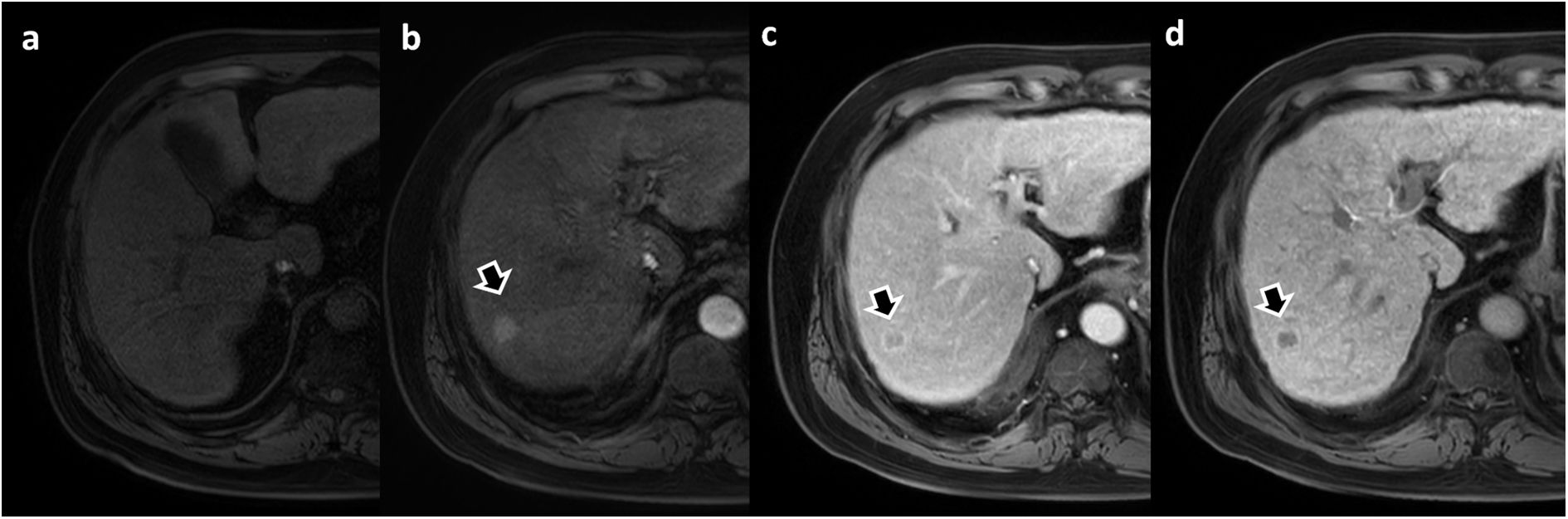

Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH). Arrows in images a-c show three contrast-enhancing lesions from three different patients characterised as FNH during the hepatobiliary phase with Gd-BOPTA. Images d–g show the dynamic study of the patient in image a. The lesion appears slightly hyperintense on non-contrast T1 (d), marked enhancement during the arterial phase (e) and progressive homogenisation with the liver parenchyma in the portal (f) and late (g) phases.

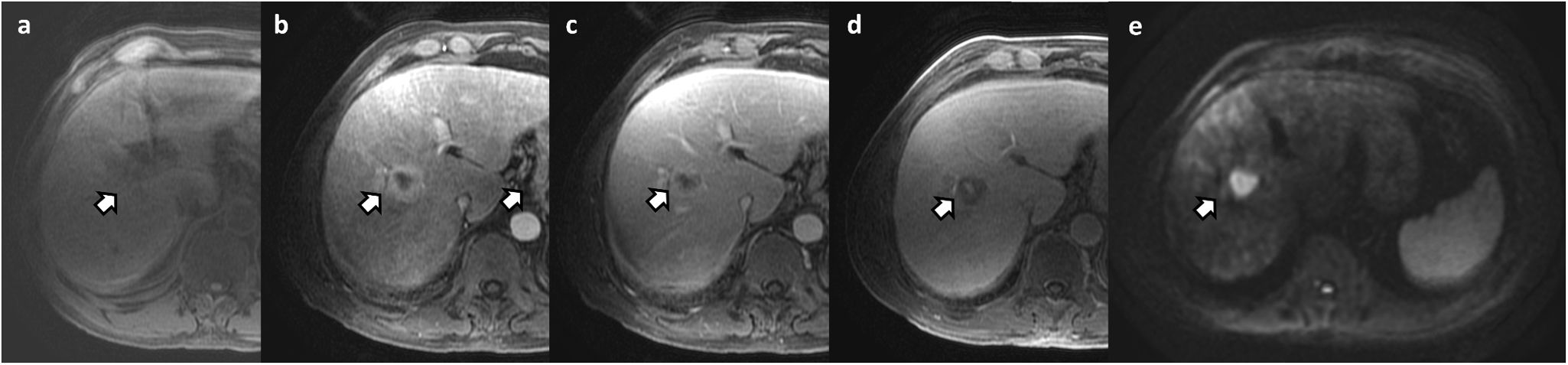

Inflammatory subtype hepatocellular adenoma (biopsy-confirmed) in a 35-year-old patient on oral contraceptives. The lesion appears hyperintense on T2-WI (a) compared to the liver parenchyma, a typical finding with the inflammatory subtype. In the in-phase and out-of-phase sequences (b and c), a drop in signal can be seen in part of the lesion due to the presence of intracellular fat (also see a drop in signal in the liver parenchyma due to c). In the dynamic study (d, T1-WI without IVC; e, arterial phase; f, portal phase; and g, hepatobiliary phase) note the marked hypointensity during the hepatobiliary phase (g).

HFN1α-inactivated adenoma has a low risk of complications when less than 5 cm in size. Its association with the use of oral contraceptives and obesity is lower than in the case of inflammatory adenoma, which is strongly associated. Both subtypes have a higher incidence in females and are the most common subtypes.

Beta-catenin-mutated adenomas are a group of adenomas with mutations in the CTNNB1 (catenin β-1) gene in exon 3 or in exon 7/8. The mutation in exon 3 leads to a high risk of malignancy (up to 40%) and mutation in exon 7/8 means a high risk of bleeding with a lower risk of malignancy. The exon 3 mutation is associated with the use of anabolic steroids and males.21,22.

A classic systematic review concluded that the signal intensity of the tumour in the HBP had a high diagnostic performance for differentiating FNH from HCA, with a sensitivity of 91–100% and a specificity of 87–100% for the diagnosis of FNH.23 FNH is the most common disorder presenting with iso- or hyperintensity uptake by the lesion during HBP. However, this feature is not exclusive to FNH and can also be observed in certain HCA subtypes and even in some well-differentiated HCC. For example, up to 83% of mutated β-catenin adenomas show iso- or hyperintensity during HBP.24

A more recent systematic review25 included 410 cases of HCA and found that 14% exhibited iso- or hyperintensity during HBP. When this behaviour was analysed based on pathological subtypes, the percentage varied from 0% of HNF1α-inactivated adenomas to 59% of mutated β-catenin. In inflammatory and unclassified adenomas, the proportion was 14% and 11% respectively. In this same review, the specificity of iso- or hyperintensity of the lesion in the HBP to differentiate FNH from HCA was 89% if all HCA subtypes were included. However, this specificity dropped to 65% if only mutated β-catenin and unclassified subtypes were included. The authors concluded that the high diagnostic yield of iso- or hyperintensity in HBP was due to the low prevalence of these subtypes, especially of mutated β-catenin. This may be a significant problem in clinical practice since, as previously mentioned, the β-catenin subtype mutated in exon 3 is the subtype with the highest risk of malignancy among adenomas.

Therefore, although signal intensity in HBP has traditionally been used as a simple way of differentiating HCA from FNH, most of these studies did not consider adenoma subtypes and these two disorders cannot be differentiated solely by signal intensity in HBP. For precise characterisation, this must be combined with other characteristics, such as the presence of intracellular lipids in the HNF1α-inactivated adenoma, or the marked hyperintensity in T2-weighted images and the atoll sign in the inflammatory adenoma.22

Focal nodular hyperplasia-like lesionsChemotherapy treatments, especially those based on oxaliplatin used in patients with pancreatic or colorectal cancer, can induce the formation of regenerative lesions similar to focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH-like) in the liver. The development of FNH-like lesions and their detection in follow-up studies of patients with gastrointestinal cancer can lead to errors, as they can be confused with metastasis, with the risk of inappropriate treatment changes and even unnecessary invasive procedures. FNH-like lesions have a typical behaviour on MRI, with the presence of enhancement during the arterial phase and hyper- or iso-intensity during the HBP.26 The presence of a hyperintense ring at the periphery of the regenerative lesion in HBP is also characteristic of up to 50% of oxaliplatin-induced lesions.27

In patients with liver disease after Fontan surgery, a flow diversion technique between the inferior vena cava and the pulmonary artery for patients with congenital heart defects, it is common for benign hypervascular regenerative lesions to develop with an appearance similar to FNH. In this context, in addition to the appearance described above, some of these FNH-like lesions may show features typical of HCC, such as washout during the portal phase, which sometimes makes diagnosis difficult.28,29

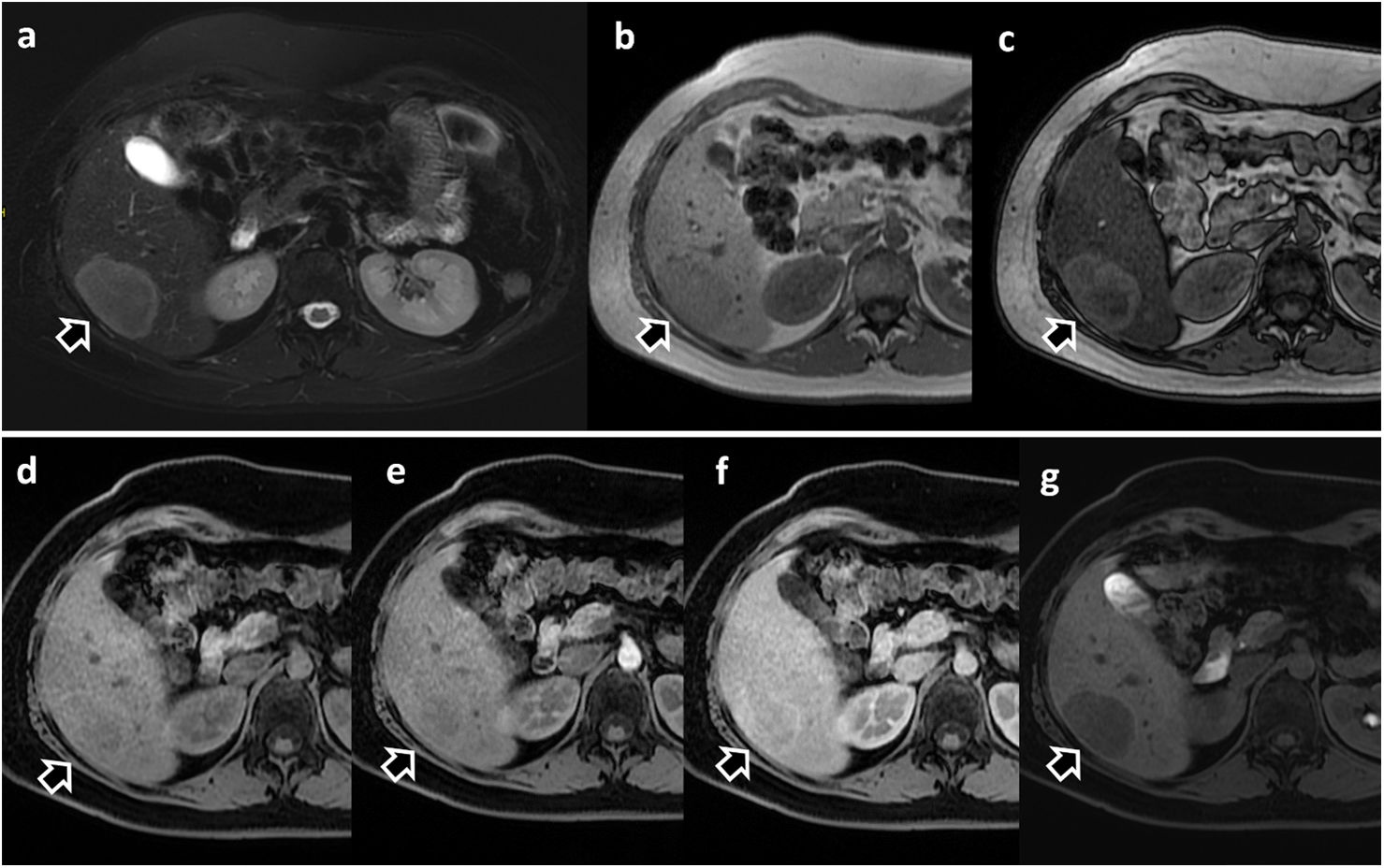

Over 30% of patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome develop FNH-like lesions.30 Unlike FNH, these lesions may appear hyperintense on T1-weighted images and hypointense on T2-weighted images, when compared with the rest of the liver parenchyma. It is typically common to find arterial enhancement and contrast retention in the lesion during HBP (Fig. 5).26,30

Focal nodular hyperplasia-like (FNH-like) lesions in two different patients. (a) 45-year-old woman with Budd-Chiari syndrome and multiple FNH-like lesions, with Gd-BOPTA. Note the presence of the lesion marked with an arrow, hypointense compared to the rest of the parenchyma in T2-WI sequence (a) and hyperintense in T1 (b). The lesion shows arterial enhancement (c); arterial phase with subtraction) and hyperintensity during HBP (d). (e–g) 23-year-old man with Fontan procedure and liver MRI with Gd-EOB-DPTA. Multiple focal hepatic lesions with FNH-like features may be seen. They show hyperintensity in T1 without IV contrast (e) with enhancement during the arterial phase (f), isointensity during the portal phase (g) and marked hyperintensity during the hepatobiliary phase (h).

The vast majority of hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC) develop in patients with liver cirrhosis. The non-invasive diagnosis of this primary liver cancer is accepted in patients with chronic liver disease when specific characteristics are demonstrated in the dynamic behaviour of the lesion after the administration of the contrast medium. According to the European EASL guidelines,31 a non-invasive diagnosis of HCC can be established when all these criteria are met: nodules larger than 1 cm that show hyperenhancement in the arterial phase; and washout during the portal or equilibrium phase. The LI-RADS v201811 criteria allow for the definitive diagnosis of HCC and also include other imaging features such as the presence of pseudocapsules during the portal phase and nodule growth in serial studies (Fig. 6).

Patient with HBV cirrhosis. Dynamic liver MRI with Gd-EOB-DPTA. Focal liver lesion with definitive criteria for hepatocellular carcinoma: presence of enhancement in the arterial phase (b), with washout and pseudocapsule formation during the portal phase (c) and hypointensity during the hepatobiliary phase (d).

Unlike the previous EASL and LI-RADS criteria, in which the presence of hypointensity in the HBP is not considered a major criterion and it differs in the tumour washout, some of the main Asian diagnostic guidelines, such as the KLCA-NCC from South Korea16 or the JSH-HCC from Japan,32 consider hypointensity in the HBP as washout, provided it can be ruled out that the session is behaving like a haemangioma, due to its high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, or an intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, due to its target appearance on the diffusion-weighted image. This discrepancy between the European/US and Asian guidelines is based on the fact that the diagnostic criteria seek "high specificity" or "high sensitivity" respectively, depending on the incidence of the disease in each region33 and on the therapeutic approach, liver transplantation or local treatments.15,34

The hypointensity of HCC lesions is due to the loss of membrane transporters with cell dedifferentiation. Decreased expression of OATP1B3 is one of the alterations that occur in hepatocarcinogenesis, which is why most HCC appear hypointense in HBP.35 The LI-RADS criteria consider hypointensity during this phase as an auxiliary criterion suggestive of malignancy, and isointensity or hyperintensity of the lesion during this phase as a criterion that suggests it may be benign. However, we must remember that 9%–14% of HCC can show hyperintensity in the HBP due to over-expression of the OATP8 transporter, with these being well-differentiated HCC with a better prognosis.36,37

In recent years, the widespread use of hepatobiliary contrast media has generated a growing interest in hypointense nodules in HBP which do not show enhancement in the arterial phase.38 It is generally recognised that these lesions may represent early stages of HCC, as during the process of hepatocarcinogenesis, the decreased expression of the OATP8 transporter37 occurs before the development of the characteristic changes in tumour vascularisation. Adequately identifying and characterising these nodules and their progression to hypervascularised nodules through closer follow-up enables early treatment of HCC.

In a retrospective multicentre study with patients at high risk of developing HCC, nodules ≤ 30 mm which were hypointense on HBP and without enhancement in the arterial phase corresponded in 44% of cases to advanced HCC, in 20% to early HCC, in 28% to high-grade dysplastic nodules, and only in 8% to low-grade dysplastic nodules or regenerative nodules.39 In an attempt to more accurately determine the likelihood of malignancy, predictive factors for hypervascular transformation of these nodules have been described: size > 10 mm; the presence of hyperintensity on T2-weighted images; restriction on diffusion-weighted images; and the existence of a previous HCC.13

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomaIn patients with cirrhosis, image screening for HCC also enables the detection of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma lesions in early stages. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma usually presents as a lesion with peripheral or ring enhancement in images obtained in the arterial phase and with centripetal enhancement in the portal or late phases, although sometimes it is difficult to differentiate between the two conditions in patients with cirrhosis (Fig. 7). In HBP, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma has been described to behave as a tumour with a poorly defined central area of greater signal intensity at its edges, called an "EOB-cloud", and surrounded by a hypointense margin.40 However, this behaviour is not common in cholangiocarcinomas on cirrhotic liver.

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in a patient with liver cirrhosis. Liver MRI with Gd-BOPTA (a), without contrast; (b) arterial phase; (c) portal phase; (d) hepatobiliary phase; (e) diffusion with b = 800) showed a lesion with arterial ring enhancement (b) that persisted during the portal phase (c). In the hepatobiliary phase (d), note the hypointensity of most of the lesion with a hyperintense central zone, probably due to contrast retention in the extracellular matrix. Restricted diffusion can also be seen (e). The lesion was biopsied and the diagnosis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma was confirmed.

The International Working Party Classification of Hepatocellular Lesions divides lesions in this context into regenerative and dysplastic/neoplastic.41 Regenerative lesions include monoacinar regenerative nodules, 1−3 mm in size and consisting of a single portal space, and multiacinar or large regenerative nodules, consisting of more than one portal space. When these lesions are found in liver cirrhosis, they are called monoacinar or multiacinar cirrhotic nodules, respectively.42 Regenerative nodules associated with liver cirrhosis usually show a signal intensity similar to that of the liver parenchyma in the images obtained in HBP, although occasionally they may appear hyperintense. Within the regenerative lesions, in up to 6% of patients with cirrhosis, so-called HBP-doughnut nodules can be observed. These nodules do not enhance during the arterial phase and correspond to the multiacinar cirrhotic nodules described in histology.42 Dysplastic nodules are often iso- or hyperintense in HBP due to preserved expression of OATP1B3 transporters. However, up to a third of these high-grade dysplastic nodules may be hypointense in HBP.35 We see that hypointensity of a nodule in the HBP in the presence of chronic liver disease is a warning sign and criterion for early follow-up.

Detection of liver metastasesMetastases are the most common type of malignant liver tumour.43 The use of MRI with hepatobiliary contrast media and the acquisition of images in HBP has improved the diagnostic performance in metastasis detection, with a diagnostic yield superior to CT and MRI with extracellular contrast media (Fig. 8).

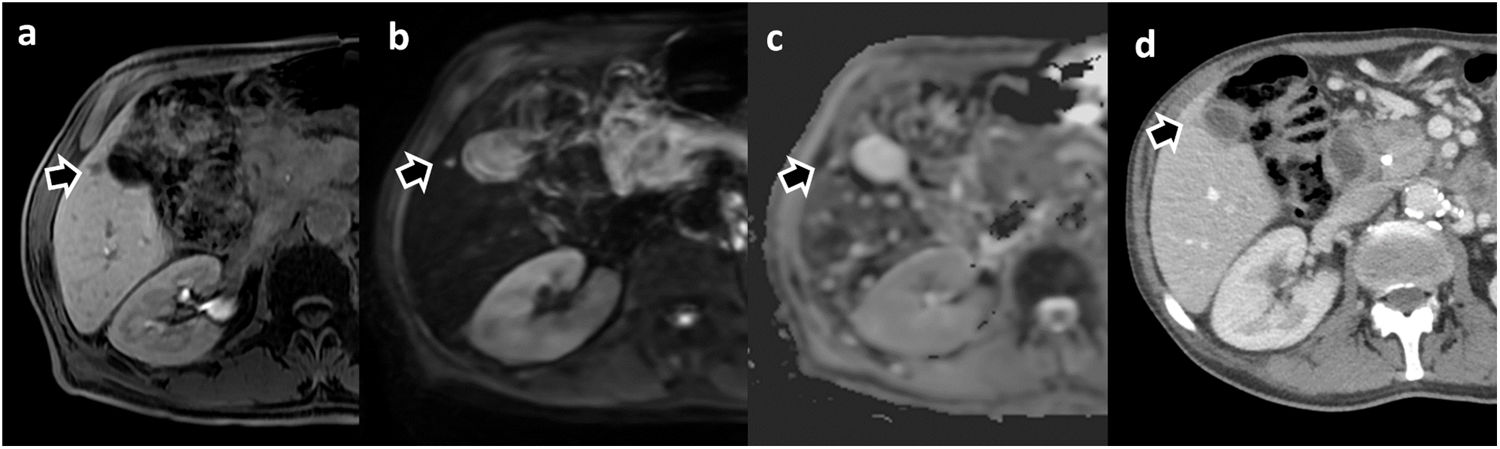

Small liver metastasis in a patient with pancreatic adenocarcinoma detected on liver MRI with Gd-BOPTA. (a) Hepatobiliary phase, (b) Diffusion-weighted sequence (b = 800) and (c) Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map. In a prior CT study performed for local staging (d), the lesion was not detected and is difficult to identify. The metastatic lesion was confirmed by biopsy.

The combination of diffusion-weighted and HBP imaging is the best strategy for maximising the detection of metastases. In a meta-analysis that included 39 studies, the combination of diffusion sequencing and HBP obtained the highest sensitivity, with 96% for metastasis detection. The combination improved sensitivity compared to the isolated use of either (87% and 91% respectively).44 This study showed similar results even for metastases smaller than 1 cm in size. Other studies have compared the use of conventional MRI protocols with full dynamic study versus abbreviated protocols (including T2-weighted, diffusion-weighted and HBP images) for the detection of metastases in colorectal cancer, and obtained similar metastasis detection rates with both protocols.45

In the investigation of liver metastases from neuroendocrine tumours, the combination of HBP and the diffusion sequence also had the highest detection rate compared to the rest of the sequence combinations and showed sensitivity and specificity of 86% and 94% respectively.46 In the same study, this combination was statistically significant in showing the highest interobserver agreement. Another study showed that the HBP sequence had the highest contrast/noise ratio for the detection of liver metastases from neuroendocrine tumours.47 These studies suggest using hepatobiliary contrasts in the assessment of patients with suspected metastasis from neuroendocrine tumours (Fig. 9).

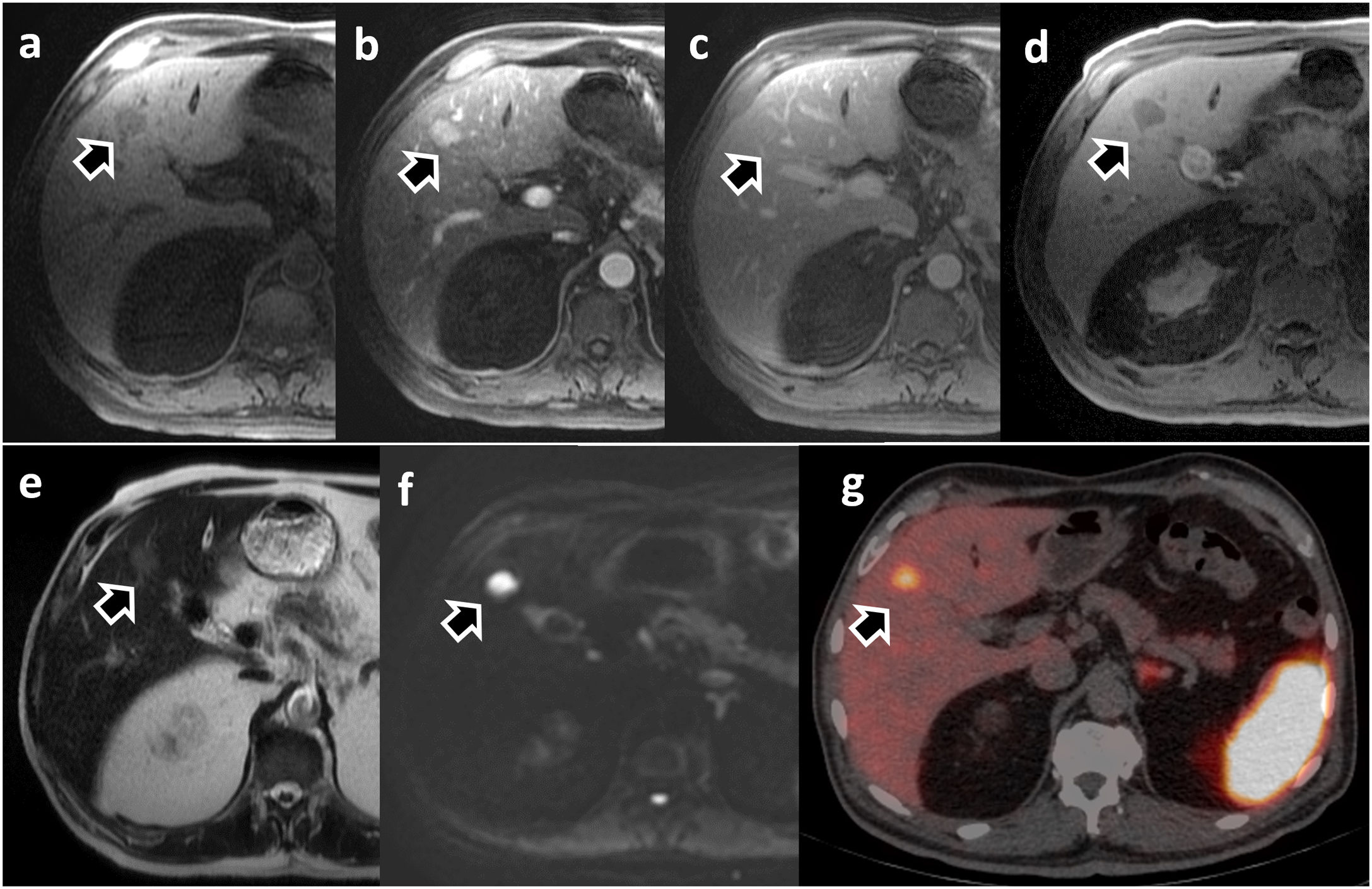

Patient with liver metastasis from ileal neuroendocrine tumour. Dynamic liver MRI with Gd-BOPTA (a–f): a) non-contrast phase; (b) arterial phase; (c) portal phase; (d) hepatobiliary phase; (e) T2-WI; (f) diffusion with b = 800); and PET/CT with Ga-68-DOTATATE (g). The lesion is hypervascular during the arterial phase (b), barely visualised during the portal phase (c), and is markedly hypointense in HBP (d), as well as hyperintense in the diffusion sequence (f). The PET/CT confirmed the presence of somatostatin receptors in the lesion (g).

Most liver metastases are hypointense in HBP due to the absence of hepatocytes and membrane transporters. However, some lesions, mainly adenocarcinoma metastases, show a relatively hyperintense central zone during HBP, which has the same cloud enhancement behaviour as that observed in cholangiocarcinoma. This uptake is probably due to the accumulation of contrast in the extracellular matrix with fibrosis or its diffusion in the area of central necrosis.36

Assessment of the biliary tract and liver functionObtaining images during biliary excretion of hepatobiliary contrast enables a detailed study of the biliary tree, both for preoperative assessment in procedures considered complex and to demonstrate the presence of bile leaks, even from small branches.

In the assessment of living liver donors for liver transplantation, the addition of 3D T1-weighted cholangiogram sequences after hepatobiliary contrast administration improved visualisation of second-order bile ducts and increased diagnostic confidence in the assessment of biliary anatomy compared with T2-weighted MR-cholangiogram sequences.48

Bile leak is one of the main complications of liver surgery, and occurs with an incidence of 4–10%. It causes an increase in morbidity with prolonged hospital stay and an increased mortality rate.49 In a study evaluating hepatobiliary contrast-enhanced MR cholangiography in patients with bile leaks lasting more than one week, 100% accuracy was achieved in detection and localisation.49 This avoided the need for invasive direct cholangiography and identified peripheral leaks amenable to conservative treatment.

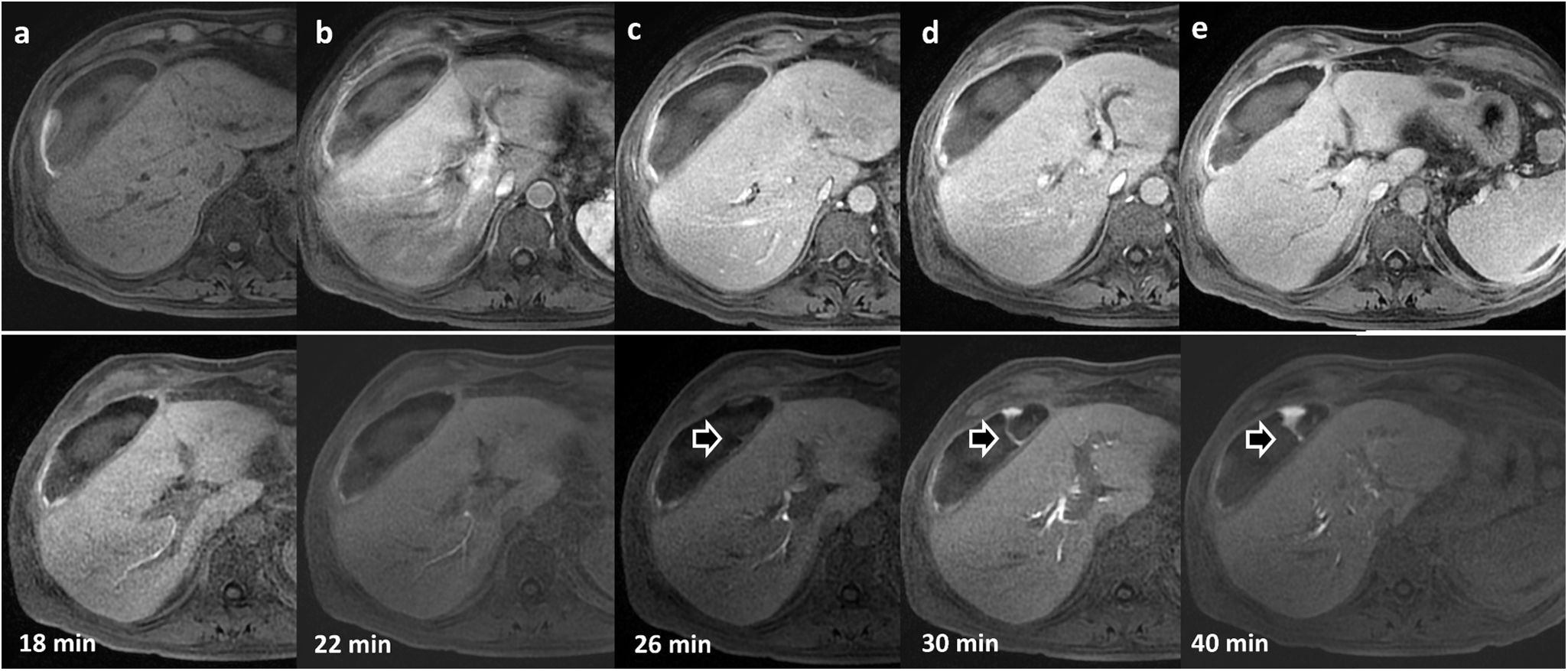

In our experience, in patients strongly suspected of having bile leak who also have perihepatic collections, it is advisable to perform an MR cholangiogram, acquiring the images later than the usual HBP, as sometimes the excretion is slowed and the leaks may go undetected in the early stages of biliary excretion (Fig. 10).

62-year-old patient with collection detected on ultrasound after cholecystectomy. Dynamic liver study with Gd-EOB-DPTA. Top row: (a) without contrast; (b) arterial phase; (c) portal phase; (d) late phase; (e) transition phase. Bottom row: sequential uptakes during the hepatobiliary phase and additional uptakes that allow the identification of extravasation of the contrast material (arrows) towards the collection in the images at minutes 26, 30 and 40.

The degree of liver enhancement is directly related to the mass of functioning hepatocytes and their efficiency in incorporating the contrast medium. Areas of the liver with reduced function or damaged hepatocytes will show less enhancement. This differential behaviour makes it possible to assess liver function. HBP MRI has become integrated into clinical practice and offers an excellent non-invasive method for assessing liver function. Several studies have shown that the combination of radiomics and clinical variables with deep learning models can effectively stratify hepatic functional reserve in patients with liver disease.50,51

ConclusionsHepatobiliary contrast media enable better detection and characterisation of focal liver lesions in most clinical situations, both in cancer patients, patients with chronic liver disease and patients with lesions likely to be of hepatocellular origin. In addition, they facilitate the assessment of bile duct lesions and of the functional capacity of the liver parenchyma, which significantly increases confidence and safety in the diagnosis.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for the integrity of the study: APG, JML and LMB.

- 2.

Study conception: not applicable.

- 3.

Study design: not applicable.

- 4.

Data collection: not applicable.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: not applicable

- 6.

Statistical processing: not applicable

- 7.

Literature search: APG, JML and LMB.

- 8.

Drafting of the article: APG, JML and LMB.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: APG, JML and LMB.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: APG, JML and LMB.