Suplement “Update and good practice in the contrast media uses”

More infoContrast media (CM) were first used soon after the discovery of X-rays in 1895. Ever since, continuous technological development and pharmaceutical research has led to tremendous progress in radiology, more available techniques and contrast media, and expanded knowledge around their indications.

A greater prevalence of chronic diseases, population ageing, and the rise in diagnosis and survival times among cancer patients have resulted in a growing demand for diagnostic imaging and an increased consumption of CM.

This article presents the main lines of research in CM development which seek to minimise toxicity and maximise efficacy, opening up new diagnostic and therapeutic possibilities through new molecules or nanomedicine. The sector, which is continuously evolving, faces challenges such as shortages and the need for more equitable and sustainable practices.

La historia de los medios de contraste (MC) comienza poco después del descubrimiento de los rayos X en 1895. Desde esos pasos iniciales, un proceso de desarrollo tecnológico continuo y de investigación fármaco-química, están conduciendo a una enorme evolución de la radiología, ampliando las técnicas disponibles, los medios de contraste y sus indicaciones.

La mayor prevalencia de enfermedades crónicas, el envejecimiento poblacional y el aumento de diagnóstico y supervivencia en los pacientes oncológicos han supuesto una demanda creciente de pruebas radiológicas y simultáneamente, un continuo incremento del consumo de MC.

En este trabajo presentamos las principales líneas de investigación en MC que buscan minimizar la toxicidad y maximizar la eficacia, abriendo nuevas posibilidades diagnósticas y terapéuticas a través de nuevas moléculas o la nanomedicina. Al mismo tiempo el sector enfrenta desafíos como el desabastecimiento y la necesidad de prácticas más igualitarias y sostenibles reflejando un campo en constante evolución.

Contrast media (CM) were first used soon after the discovery of X-rays in 1895. The poor differentiation of soft tissues in the first radiological images led in 1896 to scientists such as Hascheck and Lindenthal obtaining the first radiological images after injecting radiopaque substances into cadavers.1 However, the heavy metal salts used in these early experiments were highly toxic, preventing their use in living humans. In the early 1920s, Osborne et al.2 observed radiopaque behaviour in urine from subjects with syphilis treated with iodinated compounds. From then on, there was extensive development of iodinated contrasts in subjects, with the first angiogram with sodium iodide being performed in 1924.3

Since these initial steps over 100 years ago, there has been continuous technological development, combined with pharmacological-chemical research, which has led to an enormous evolution in diagnostic imaging, with the spread of available techniques, contrast media and their indications.

The increasing prevalence of chronic diseases, an ageing population, increased diagnosis and survival of cancer subjects and those with complex comorbidities has led to a growth in diagnostic imaging tests4,5 and, simultaneously, a significant increase in the use of CM.

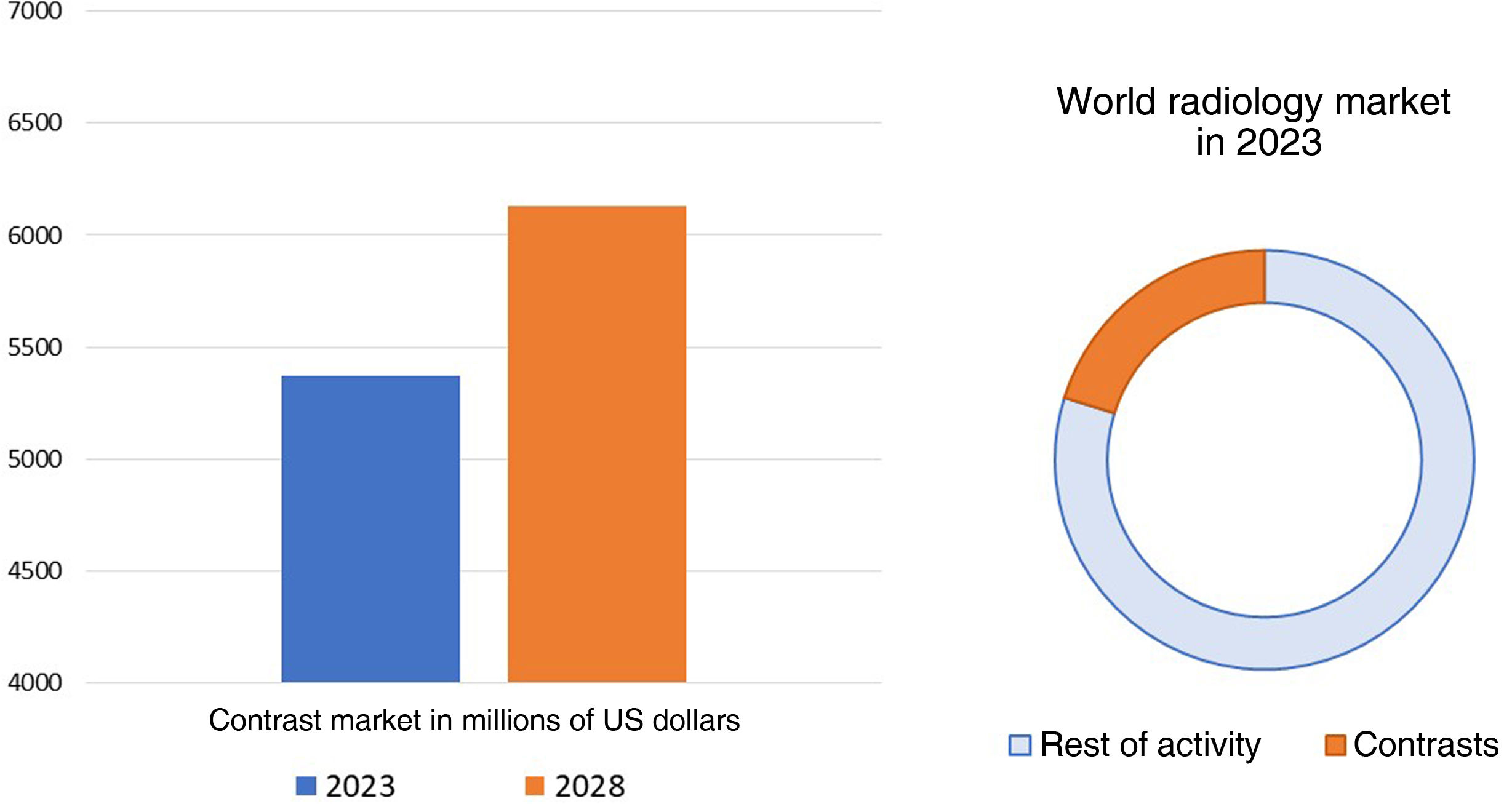

The medical imaging industry (which includes technological equipment, software and consumables) was valued at 26.6 billion dollars in 2021 and is expected to reach 43.04 billion dollars in 2029, which would represent a compound annual growth rate of 6.20% in the period 2022−2029. CM form a very important part of this worldwide radiological market. The world CM market was valued at 5.37 billion dollars in 2023 and is expected to exhibit a compound annual growth rate of 2.71% from 2023 to 20306 (Fig. 1).

Evolution of the contrast media market. The CM market currently accounts for 25% of the entire radiology industry. It is expected to grow from 5.37 billion dollars in 2023 to 6.13 billion in 2028. Adapted from: Mordor Intelligence Research & Advisory.6

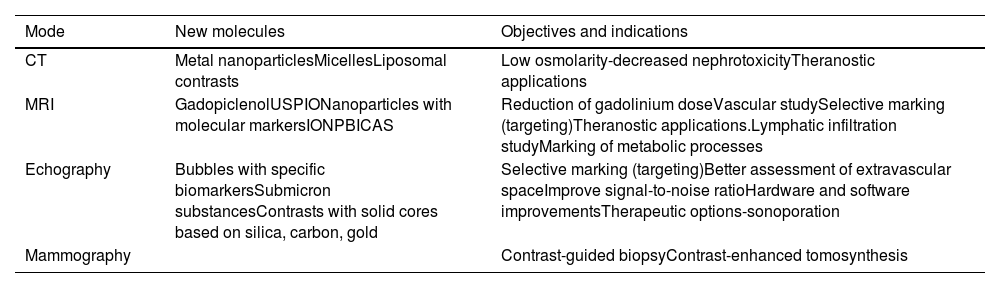

In this article, we have aimed to show the main challenges and lines of investigation in CM (Table 1) which, alongside technological development and bioinformatics, will form the bases of growth in our speciality and define the radiology of the future.

Development pathways for new contrast media in the form of new molecules or new indications.

| Mode | New molecules | Objectives and indications |

|---|---|---|

| CT | Metal nanoparticlesMicellesLiposomal contrasts | Low osmolarity-decreased nephrotoxicityTheranostic applications |

| MRI | GadopiclenolUSPIONanoparticles with molecular markersIONPBICAS | Reduction of gadolinium doseVascular studySelective marking (targeting)Theranostic applications.Lymphatic infiltration studyMarking of metabolic processes |

| Echography | Bubbles with specific biomarkersSubmicron substancesContrasts with solid cores based on silica, carbon, gold | Selective marking (targeting)Better assessment of extravascular spaceImprove signal-to-noise ratioHardware and software improvementsTherapeutic options-sonoporation |

| Mammography | Contrast-guided biopsyContrast-enhanced tomosynthesis |

CT: computed tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; USPIO: ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide particles; IONP: iron oxide nanoparticles; BICA: biogenic contrast agents.

Computed tomography (CT) is certainly one of the imaging methods to have evolved the most in the field of radiology, not only in terms of the improvement in image quality and resolution, but also in its accessibility. In addition to helical technology, the increase in the number of detector rows and iterative reconstruction, since 2006 equipment has been available with spectral technology, which consists of acquiring images with two different energy spectra. The behaviour of iodine in spectral studies causes it to be visualised with greater attenuation in low-energy maps, meaning the use of CM can be optimised in these devices, performing research studies with lower contrast concentrations and volume.7–9

The iodinated CM used in CT have also evolved since they were first introduced in 1923.10 Due to their known undesirable effects, such as nephrotoxicity and adverse reactions, these contrasts have evolved into the current generation of low osmolality contrast media.12 The current CM have a limitation due to the rapid passage of the intravascular medium towards highly vascularised organs and tissues, and their half-life is short, making large doses of contrast necessary for correct opacification of the target organ.

The contrast medium of the future will obviously need to be non-toxic and non-immunogenic. It must be as radiopaque as possible, have an adequate half-life and be safe, economical and ecologically sustainable.11,12 Side effects of CM in CT are more common when the osmolarity exceeds 800 mOsm/kg; the search for low osmolarity is therefore one of the major avenues for CM development in CT. Work is being done on creating CM with high contrast efficiency in a smaller volume and searching for other molecules with much higher X-ray attenuation characteristics than iodine.

Nanomedicine, through the introduction of nanoparticles, has opened new possibilities of incorporating metallic elements as CM in CT. These particles can be in the form of an alloy or a single component. Among them, gold nanoparticles (GNP) and silver nanoparticles (SNP) have been the most studied so far. Compared to iodine-based contrast agents, GNP exhibit 2.7 times greater attenuation than iodine, with high stability and low immunogenicity, in addition to having the potential to be combined with therapeutic agents.12–15

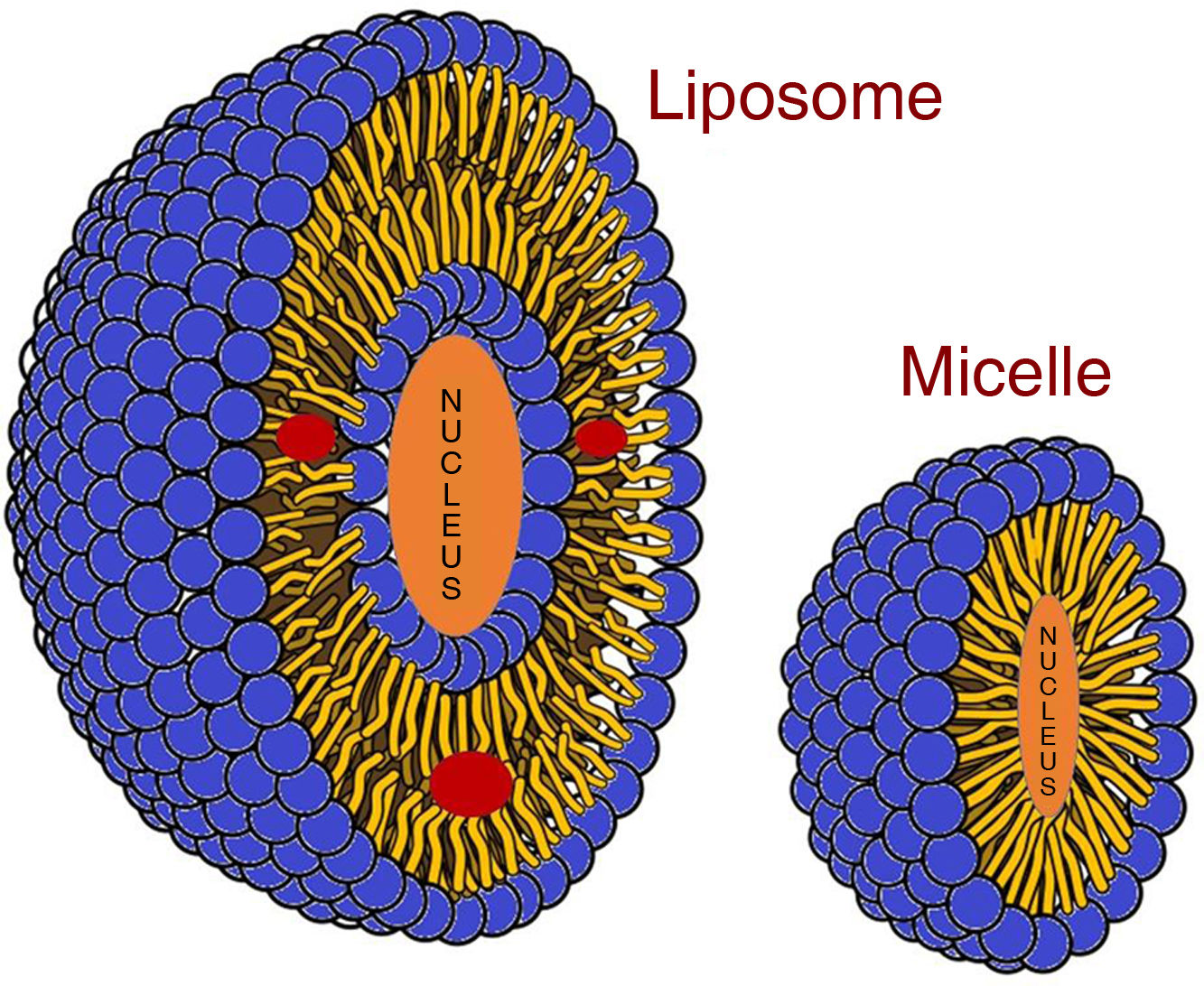

Other examples of nanoparticles under investigation are micelles and liposomal contrast media (Fig. 2). Micelles are supramolecular assemblies composed of a hydrophobic core covered by a hydrophilic layer and can be "loaded" with a radiopaque contrast medium or other nanoparticles, such as GNP. Liposomal contrast media differ from micelles because they are made up of a lipid bilayer and a lipophilic core, and can be "loaded" not only with radiopaque contrast media, but also with other hydrophilic components or a combination of both. Due to their small size, both can reach tumour tissue by taking advantage of their neovascularisation.15 Nanoparticles therefore open up a future in which contrasts would not only have diagnostic value, but also therapeutic value; this is known as theranostics, the combination of specific diagnosis and targeted and personalised therapy.13

Graphical representation of the mechanism of contrast incorporation into micelles and liposomes. Micelles are spherical structures with a single layer of phospholipids. The hydrophobic regions are located inside the micelle, while the hydrophilic regions are exposed to the outside. Micelles can encapsulate hydrophobic substances in their core, making them useful for transporting water-insoluble drugs or contrast agents which would otherwise be difficult to deliver. Liposomes are vesicles formed by a lipid bilayer that encapsulates a volume of aqueous solution in its core. Unlike micelles, liposomes can contain and transport both hydrophilic substances in their core and hydrophobic substances in their bilayer (red circles in the image). Adaptation of an original drawing by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal.

One of the first therapeutic targeting pathways was the union of chemotherapy drugs with antibodies or specific protein markers which act as cell recognition molecules. Antibody-drug conjugates bind to specific antigens overexpressed in different cancer subtypes and therefore actively target treatment to these cells. Nanoparticles promise to improve the efficacy and monitoring of targeted therapy; they offer protection to chemotherapy agents and improve their pharmacokinetics and, combined with CM, allow monitoring to ensure that the treatment reaches the tumour tissue.

The future in CT is promising, not only thanks to the new CM and their therapeutic potential, but also thanks to the development of multi-energy technology, with photon counting CT being its most recent variant, allowing for better tissue characterisation through a lower use of both ionising radiation and CM.16 This, together with the analysis of data extracted from images using radiomics and the advancement of artificial intelligence, means that CT will become a personalised diagnostic method so that each subject is given a different CM according to their biometry, their risk factors, their underlying disease and, in all likelihood, their genetic make up.15,16

Magnetic resonance imagingCM in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are substances capable of modifying T1 and T2 relaxation times, thus increasing tissue contrast. Currently, the majority of CM in MRI are Gadolinium (Gd)-based molecules, having completely displaced iron- or manganese-based compounds.17,18

Within the evolution of Gd-based contrasts, the main line of work is the optimisation of their dose to avoid undesirable renal effects and the risks associated with their accumulation in the central nervous system.18 One recently approved is Gadopiclenol, a macrocyclic CM with high relaxivity, making it possible to reduce the conventional dose of Gd by half (0.05 mmol/kg) and thus reduce the risks, especially in people who require repeated examinations.19,20

In the field of kinetics, there is the promise of a field of new applications with the use of CM based on ultra-small superparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) particles, particularly in vascular studies. The first compound investigated in this group was ferumoxytol.21 Unlike gadolinium-based contrast agents, ferumoxytol remains in the intravascular space with a long half-life of 14–21 hours and with minimal parenchymal enhancement. This contrast dynamic enables a high level of vascular enhancement with small vessel visualisation and extended acquisition times, opening up a promising future, particularly in a magnetic resonance angiogram, presurgical vascular study in cancer subjects, and assessment of atheromatous plaques.

The great challenge with CM in MRI is the selective fixation to certain target molecules which allow the contrast to be directed to certain tissues, organs or even pathogens, specifically marking them.17

The first application was in the liver with hepatobiliary contrasts; the most widely used today is gadoxetic acid.22 This ionic, paramagnetic, hydrophilic contrast has particular pharmacokinetics, as after the extracellular distribution phase it is taken up by functioning hepatocytes and up to 50% is excreted via the biliary tract, in the case of disodium gadoxetate (Primovist®). This property means it can be used to characterise hepatic metastases, increasing sensitivity and specificity compared to other contrast media; it increases sensitivity in the detection of liver metastases and enables non-invasive study of the biliary tract.22,23

Superparamagnetic iron oxidenanoparticles (IONPS) began to be used in MRI in the early 2000s, seeking selective marking of lymph nodes. IONPS penetrate the interstitium and are taken up by lymph nodes and the spleen, being retained by normal macrophages. Due to their supermagnetism, they generate a magnetic susceptibility artefact, causing a decrease in signal intensity in T2. Among other things, this serves to detect metastatic lymph nodes with a sensitivity greater than other methods, as the lack of concentration of this product in the nodes indicates the replacement of healthy tissue with pathological tissue, before changes in shape or size occur.24 However, undesirable effects such as skin discolouration, retinal deposits and a high rate of false positives in lymphadenopathy led to its disuse. They are currently only available for clinical use in the Netherlands until more evidence is available on their efficacy and safety. Nanoparticles, thanks to their binding capacities to different surface ligands of the cell membrane, enable "active" labelling.25 An example of this is human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2); this marker is present in multiple neoplasms (for example, ovarian, breast, gastric), as well as in some normal cells and turns out to be a poor prognostic factor. The binding of the HER2-IONPS ligand makes it possible to confirm tumours that express this receptor in gastric cancer.27

The study of biogenic imaging contrast agents (BICAS) is currently opening up a new field of opportunities: BICAS26 are developed from biological materials or those that imitate biological structures, such as proteins, peptides, antibodies or even viral particles, enabling functional images to be obtained of gene expression, protein activation, cell replication or other metabolic aspects.

There are BICAS which work according to the classic scheme of CM in MRI, altering the T1 relaxation time (mainly metalloproteins with paramagnetic ions) and T2 relaxation time (ferritin and magnetosomes), but BICAS make other contrast options possible, such as chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST). CEST works by selectively saturating the protons of a specific molecule with a radiofrequency pulse. When the magnetisation of the target molecules is transferred to water molecules in adjacent tissues, they alter their signal, which can be measured creating images that reflect the distribution and concentration of the initial target molecules. Molecules that can be detected in MRI using CEST include amides, amines, glutamate, glycosaminoglycans, glucose, glycogen and creatine.

Another example of BICAS can be found in compounds with overexpression of aquaporins (AQP), which improve the movement of water molecules, increasing the contrast in diffusion sequences, opening the door to the use of CM in non-routine sequences.

EchographyContrast-enhanced echography has progressed considerably over the last twenty or thirty years, with important advances in the synthesis of new compounds, in imaging techniques and in the development of new applications.28 At present, microbubbles are the only clinically approved echography contrast agent.29 They are formed by small bubbles in a gaseous state with high molecular weight and low solubility, stabilised with a thin layer of lipids, proteins or polymers, usually phospholipids or albumin. Their relatively large size determines their exclusively intravascular distribution, but they are small enough to pass through the pulmonary circulation without being destroyed.30

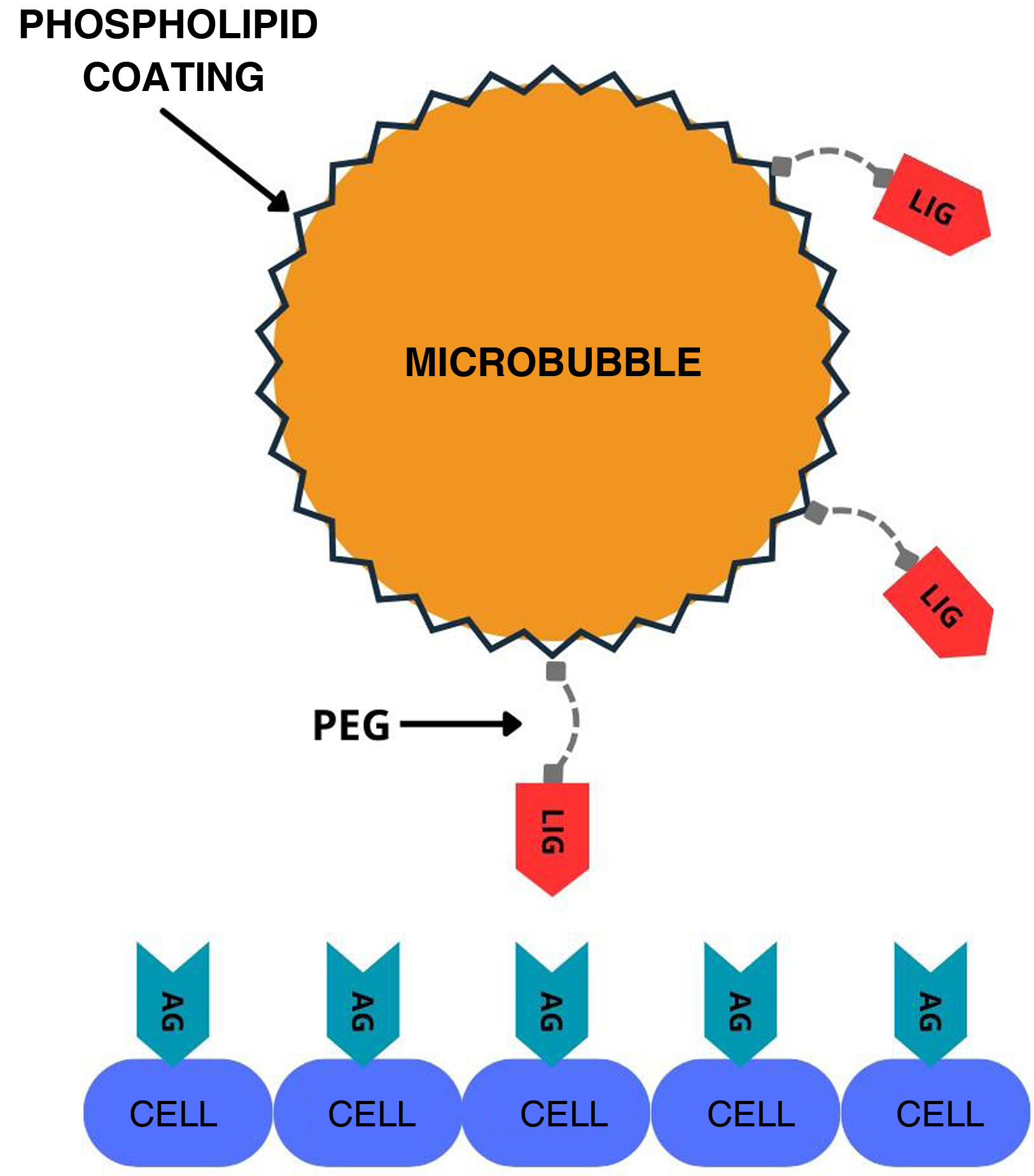

One of the lines of research in the synthesis of new substances, several years in the making, explores the development of molecularly directed contrasts through the incorporation of a peptide or antibody into the stabilising layer of the microbubble31 (Fig. 3). This modification enables it to bind to specific biomarkers expressed in endothelial cells during inflammation, angiogenesis or thrombosis.32,33 Images are obtained several minutes after contrast administration, when most of the free contrast has been eliminated, allowing specific detection of particles which have bound to the biomarker in a proportion similar to the level of expression of the target receptor.34 Despite their potential, performance is poor, even with doses 10 times higher than those of conventional contrasts, as only around 1–2 % of the administered microbubbles bind to the corresponding receptor.35,36 Markers such as VEGFR enable the identification of abnormal vessels linked to certain ovarian, breast or prostate tumours, facilitating early detection of the disease and follow-up after treatment.37,38 Other particles, such as PSGL1 glycoproteins, are capable of binding to P- and E-selectins which are expressed in some inflammatory processes.39

Graphical representation of the mechanism of action of molecularly labeled microbubbles. A ligand (LIG), usually an antibody or surface peptide that recognises antigens (AG) expressed by cells, is incorporated into the microbubble. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) helps project the ligand from the microbubble surface to increase its affinity for the antigen. Adapted from reference 37.

The so-called submicron-sized substances, nanometres in size, have greater vascular permeability than microbubbles. This feature enables their diffusion into the extravascular space, especially in diseased tissues.34,40 Within this group, phase change droplets synthesised from perfluorocarbons in liquid state vaporise into bubbles detectable by the echography scanner when an external echography or heat source is applied.41–43 Gas vesicles, recently developed and discovered in the gas vacuoles of cyanobacteria, can be genetically modified to change their constituent proteins and detect certain proteases or correlate the contrast signal with gene expression.44,45 Other micron-sized substances under investigation include nanobubbles, polymeric nanoparticles and echogenic liposomes.40,46

New contrasts with solid cores based on silica, carbon, gold or magnetic substances are also being developed, which have greater stability, better signal-to-noise ratio and greater resistance to echography compared to gaseous core contrasts.28,47

In addition to the advances in the development of new particles, significant progress is being made in hardware and software systems which enable the application of contrasts from new approaches. Superharmonic imaging, which uses third-order or higher harmonics, takes advantage of the efficiency of low-frequency excitation of microbubbles and the detection of their broadband harmonics at high frequencies.48 They offer higher resolution and better tissue contrast, but only penetrate a few centimetres deep and require ultra-high bandwidth transducers.30,49 High-resolution contrast-enhanced echography, also called ultrasound localisation microscopy, is based on obtaining ultrafast images which provide quantitative data on flow patterns in the microvasculature.50 Although still in its early stages, it is showing promising results in the evaluation of liver and breast cancer.51,52

The use of contrast agents for non-invasive estimation of vascular pressure is another area of development. Although this function has been described and studied for various decades, with conflicting results, it has recently gained prominence with the publication of promising data using subharmonics (subharmonic aided pressure estimation - SHAPE).53,54 Research in this line has significant potential in specific clinical contexts, such as the determination of the hepatic venous pressure gradient in subjects with cirrhosis.55

New applications of microbubbles in the therapeutic field are also being explored. Under certain acoustic conditions, microbubbles can cause a wide variety of effects on tissues, such as reversible increases in vascular and cell membrane permeability, a process known as sonoporation.56 Among other things, this phenomenon makes it possible to improve the local administration of drugs or the transient opening of the blood-brain barrier.57 It has shown promise in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases, some tumours, such as glioblastoma, and even in the field of radiotherapy as a radiosensitising agent.58,59

MammographyThe use of MRI as a dynamic contrast-enhanced (Gd) test for breast studies became widespread in the 1990s due to its ability to demonstrate the hypervascular nature of most breast cancers and their early enhancement after the administration of contrast. It has a sensitivity close to 100% for invasive cancers, in contrast to false positives and additional examinations generated by normal enhancement of the glandular parenchyma. The main limitation of MRI is its availability, in addition to the limitations of the technique itself (for example, cost, long scanning times, metal devices, claustrophobia), so the great improvement in this field came in 2011 with the approval by the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) of contrast-enhanced mammograms (CEM) for clinical use.60

With a performance comparable to MRI (slightly lower sensitivity but greater specificity), the indications practically overlap with those of MRI, with superior performance in subjects with dense breasts due to its greater specificity.

On the one hand, CEM is based on the increased vascular permeability in tumour neoangiogenesis, which allows for the early diffusion of contrast into the tissue. On the other, it involves the different attenuation of X-rays when passing through different densities, in this case normal tissue and tissue enhanced with iodinated contrast.61

After the injection of iodinated contrast (hypo-osmolar and water-soluble at a concentration of 300−350 mg/mL), at 1.5 ml/kg (with a maximum of 150 ml) and a flow of 2−3 ml/s, there is a pause of two minutes and then the usual projections are performed on both breasts. Two acquisitions are made on each projection, one with energy above the K threshold of Iodine (high energy), and another below (low energy), with less than one second between them. To read the study, we use low-energy images at the station, where the tissue and enhancement after contrast are observed, and recombined images, where only the enhanced tissue is shown (subtraction). High energy images are not suitable for diagnostic purposes and are not sent to the workstation.

The introduction of CEM into routine activity has changed the approach to the study of the breast in such a way that, with an initial examination, where a suspected malignant lesion is found, it provides us with local staging and interventional procedures can be planned according to whether it is a single, multiple or bilateral lesion.62 This has impacted radiology units in several ways. On the one hand, there is the need for iodinated contrast media and all the necessary material to use it, infusion pumps, storage places, as well as updating the equipment. On the other, there is the need for staff trained in the use of contrasts and action protocols for possible adverse or allergic reactions, all of which until recently were not part of the routine operation of breast radiology units.

Additionally, examination times have been slightly lengthened, both due to the technique itself and to the reception, preparation and subsequent support of subjects, with the need to adapt the schedules for both echography and biopsies, and for mammograms. At the same time, however, it has reduced the need for MRI and calling subjects back to complete the examination.

On the CEM horizon, the future appears to point more towards new clinical indications rather than new CM.61–63 FDA approval of CEM-guided biopsy equipment is eagerly awaited. This would facilitate the identification of lesions which are only detected with enhancement and cannot be recovered by echography, and which, until now, could only be approached by MRI biopsy, a long, expensive procedure that is not an option in many centres.

There are expectations for the development of contrast techniques combined with tomosynthesis, which has already widely demonstrated its utility in detecting lesions.

The broad field of CEM is being studied. Its potential applications in patients being monitored due to intermediate risk, in patients in whom MRI is contraindicated, in dense breasts where conventional mammograms is sometimes insufficient, in the assessment of responses to neoadjuvant treatment or as support to resolve doubts in complex breasts, all of which make this technique indispensable in breast radiology units.64 The growth of CEM has been exponential in recent years, despite the lack of extensive use in the majority of units in public and private hospitals. The main limitations are the availability of suitable equipment and software, reluctance in relation to patient safety, both concerning the use of contrast and the radiation dose, which could increase by up to 80% compared to conventional mammograms, and the lack of generalised acceptance by insurance companies of this technique as a valid alternative to MRI, despite the fact that in economic terms it is more efficient.

Other considerationsSupply problemsLockdowns and border closures related to the COVID-19 pandemic led to shortages of CM (especially iodine) in 2022 which were aggravated by armed conflicts that increased fuel prices and had repercussions on global trade.

In May 2022, the American College of Radiology (ACR) issued a statement with recommendations on how to address the shortage65 based on two main strategies: reducing the number of contrast-enhanced scans and/or reduction in contrast dose.

During the shortage, suppliers and hospital management, especially in the USA, had to implement strategies to remain operational without compromising subject care.66 These cost-saving strategies have provided an opportunity to re-assess protocols and indications and have reflected the potential for reducing costs and adverse effects associated with optimising the use of CM.

Sustainability and pollutionIn recent years, the concept of green radiology has gained a great deal of prominence.67 A large number of recent studies have demonstrated the environmental impact of the activity in radiology departments. The energy consumption and chemicals (CM in particular) involved in obtaining radiological images are harmful to the environment and need to be managed appropriately and safely, minimising their polluting effect.

The use of CM based on iodine and gadolinium causes contamination of drinking water systems from the urinary elimination of the contrast, which ends up affecting water deposits for consumption and irrigation.68–70 Recent investigations such as the GREENWATER study71 propose that, due to the rapid elimination of CM, subjects should remain an extra hour in the Radiology department after the CM injection so that the first urine after the examination can be collected in the hospital for subsequent recycling.

At the same time, it is estimated that 15% of the CM volumes contained in single-use syringes are not used and end up as hospital waste. This waste of material (contrast, but also plastic containers and saline solution) could be greatly reduced by using multi-use injectors, as reflected in another a recent study.72

In general, CM optimisation strategies, such as correctly defining prescribing indications, adjusting the volume of contrast used, recycling unused doses, replacing single pre-filled doses with multi-injection pumps, and implementing systems for storing and recycling subject urine, provide major advantages in terms of costs, environmental impact and subject safety.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAll authors have contributed to the conception and design of this work, the critical review of the contents and the final approval of the submitted manuscript.

FundingThis study received no specific grants from public agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit organisations.