Elastography is a novel imaging technique based on ultrasound that evaluates the deformability of tissues to help characterize lesions. It is widely used and has been validated in many tissues (e.g., liver, breast, thyroid). It is also used in the study of musculoskeletal disease. Although the use of elastography in musculoskeletal radiology is limited by the variability and heterogeneity of tissues, it is a very promising technique. In this article, we aim to review the usefulness, possible indications, limitations, and future perspectives of this technique in musculoskeletal radiology.

La elastografía es una novedosa técnica de imagen basada en los ultrasonidos que valora la deformabilidad de los tejidos para ayudar a caracterizar las lesiones. Su uso está muy extendido y ha sido validada en muchos tejidos (hígado, mama, tiroides, etc.). También se aplica en el estudio de la patología musculoesquelética, aunque con limitaciones debido a la variabilidad y heterogeneidad de los tejidos; no obstante, es una técnica muy prometedora. En este artículo trataremos de revisar su utilidad, posibles indicaciones, limitaciones y perspectivas de futuro.

The first studies on elastography, based on the physiological movement of tissues, were conducted in the 1970s by Hill1, and introduced the aptly-named concept of “remote palpation''. However, the biggest developments came in the 1980s2,3, and by the 1990s companies had started to develop different technical devices to implement the technique.

Elastography is based on the principle of tissue distortion when force is applied to it; the more rigid it is, the more it will deform. This determines the degree of tissue hardness and can be used to detect changes in the tissue, such as liver fibrosis. Tissues which deform less are considered hard or rigid and those which deform more easily are considered soft.

In the musculoskeletal system, it can be a complement to ultrasound for identifying loss of a tissue's normal elastic characteristics, in principle enabling the detection of disease before it is visible by imaging techniques (ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging).

Elasticity is determined by the elastic modulus of the tissue or Young's modulus (E), measured in kilopascals (kPa), which is the ratio between the force applied and the deformity obtained. The information is obtained before and after the force is applied, and depending on the technique, qualitative information (colour map) or quantitative information with numerical values (kPa) is obtained4,5.

According to how the force is applied, the first one to be introduced was strain elastography, in which the tissue is compared before and after a compressive force is applied; it is qualitative and is expressed on a colour scale. We can also cause distortion by applying an acoustic impulse emitted by a device in which both qualitative (colour map) and quantitative information are obtained. Of these, the most widely used is Shear Wave Elastography (SWE)6, in which the speed of the transverse waves generated by the initial pulse is measured in metres per second (m/s) and, according to the density (ρ), we obtain the elasticity (E = 3ρv2) in kilopascals (kPa)7,8.

Clinical applicationsAlthough elastography is well established and standardised in other areas, primarily in the liver, it is still in the initial phases in the musculoskeletal system. However, work is already underway and there are many publications on its application in the different tissues comprising this system6,9–13.

TendonElastography of the tendon is not simple, as on the one hand it depends on anatomical location (for example, depth, direction, size and relationship with other structures) and on the other, as the healthy tendon is a very "hard" tissue, it will sometimes exceed the measurable stiffness limit under normal conditions.

Elastographically, it is a rigid and homogeneous tissue. When the tendon is damaged, transformations take place which lead to biomechanical changes. These changes can be identified by elastography, which can be useful in the early detection of tendon abnormalities. In degenerative processes, there will be a loss of normal stiffness14, which can be recovered with reparative fibrosis13,15.

The most difficult problem in the tendon is essentially tendinopathy16, which straddles a range of aetiopathogenic factors (including mechanical and degenerative factors, overuse, etc.) that cause pain. Histologically, we see the breakdown of collagen with increased cellularity, the development of new vessels and fatty infiltration.

When these phenomena are very advanced and tendinous degeneration is evident it is called tendinosis. Ultimately, these changes can lead to tendon tears.

In the degenerated tendon, a loss of normal rigidity can be observed, which is recovered once it is repaired (Fig. 1). Elastography also permits post-surgical follow-up (Fig. 2) to check that the tendon has regained its stiffness.

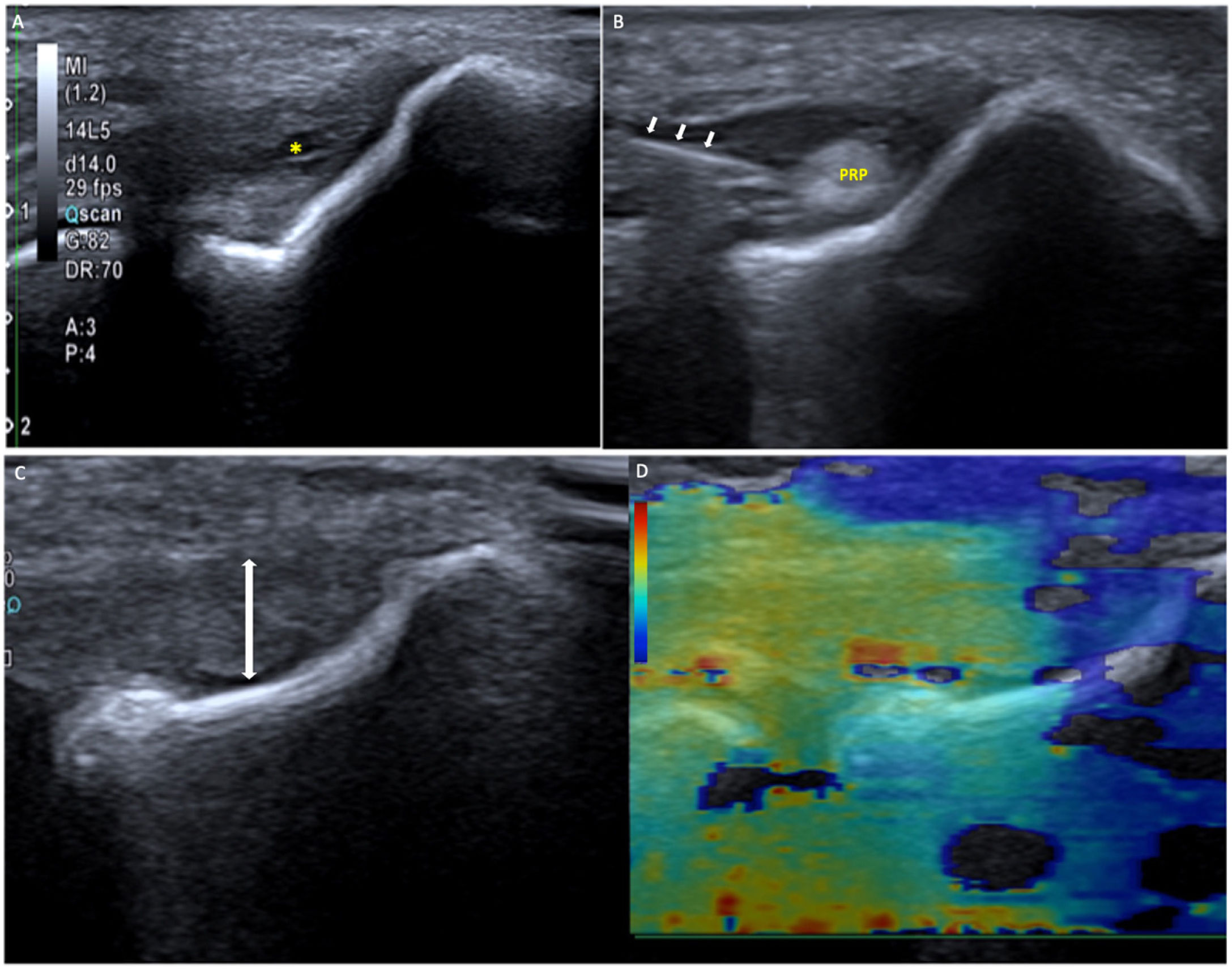

Epicondylitis treated with platelet-rich plasma (PRP). A) The ultrasound shows a hypoechoic and heterogeneous tendon, thinned due to tendinopathy, with a partial intrasubstance tear (*). B) We applied PRP in the tendinopathy (needle indicated with arrows) and filled the tear with PRP. Once the treatment was completed, after three PRP infiltrations about 10 days apart, a repeat ultrasound was performed (C): a homogeneous tendon can be seen, which has recovered its thickness (double arrow) and its stiffness. As shown in the shear wave elastography (SWE) (D), almost the entire tendon is orange-red (hard).

The reproducibility of the measurements has been demonstrated in several studies17,18. Tears will present a clear loss of stiffness. However, in this case, elastography is generally of little use because they are established lesions which are perfectly visible by imaging techniques19,20.

Although normal values have been described16,18–20, they are greatly influenced both by the tendon studied and by the device used, hence qualitative assessment of the colour map or quantitative when comparing with areas of healthy tendon or with the contralateral tendon can be more useful.

Transducer position is particularly important, since as it is an anisotropic tissue the study planes must be perfectly perpendicular or parallel. Performing it parallel to the fibres results in better quality17 and reproducibility19. Making the surface smooth and even with a good layer of gel1 helps to obtain a better image.

AchillesAnatomically, this is our largest tendon. It is easily studied as it is superficial and follows a linear path parallel to the skin. It has slight variations in elasticity, the central portion being less rigid. Its stiffness is influenced by obesity, sports activity14,17,20, age21 and the degree of muscle contraction22.

Under normal conditions, the Achilles tendon presents a fairly uniform stiffness which is lost in tendinopathy; this could be helpful as an early diagnosis to prevent more severe tendon injuries.

Elastography also allows us to assess the recovery of stiffness after surgery (Fig. 2)23.

Patellar tendonSince like the Achilles tendon it is located superficially and runs parallel to the surface, the patellar tendon is easy to assess with elastography, obtaining repeatable results with good intra- and interobserver correlation24.

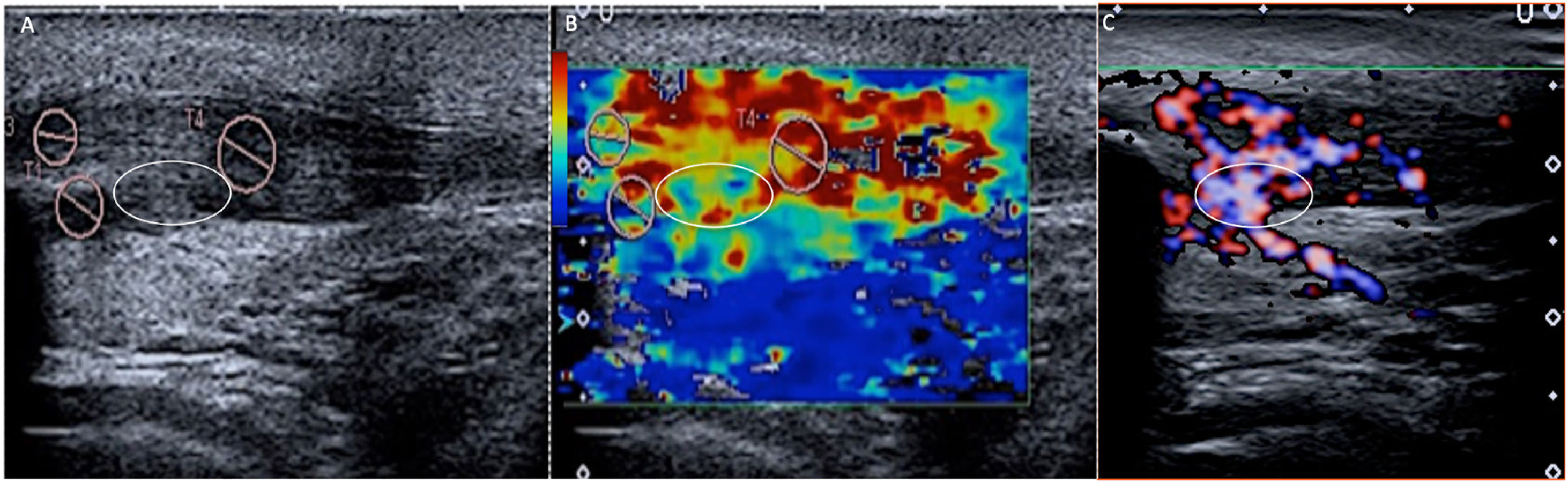

Although some studies report contradictory findings23, they are attributable to methodological differences, and it is accepted that tendinopathy and tears will be reflected in elastography as foci of loss of stiffness (Fig. 3).

Patellar tendinopathy. Image A shows the tendon hypoechoic and heterogeneous, in relation to tendinopathy. The SWE (B) shows a clear predominance of red (hard), indicating that it still maintains its stiffness. However, a focus (white oval) of blue-green (soft) tones can be seen, suggesting tendinosis, which was confirmed in the Doppler study (C), where a focus of intra-tendinous neo-vessels was identified.

Both medial and lateral epicondylitis are thought to be caused by repetitive microtraumas that cause microtears, which in terms of elastography translate into foci of loss of stiffness19,23,25,26 (Fig. 1).

Rotator cuffThe curved trajectory of the tendon and the fact that it is in contact with the bone makes assessment by elastography difficult. However, a good inter- and intra-observer correlation has been reported17,23,27. The loss of rigidity essentially allows intra-tendinous microtears to be detected.

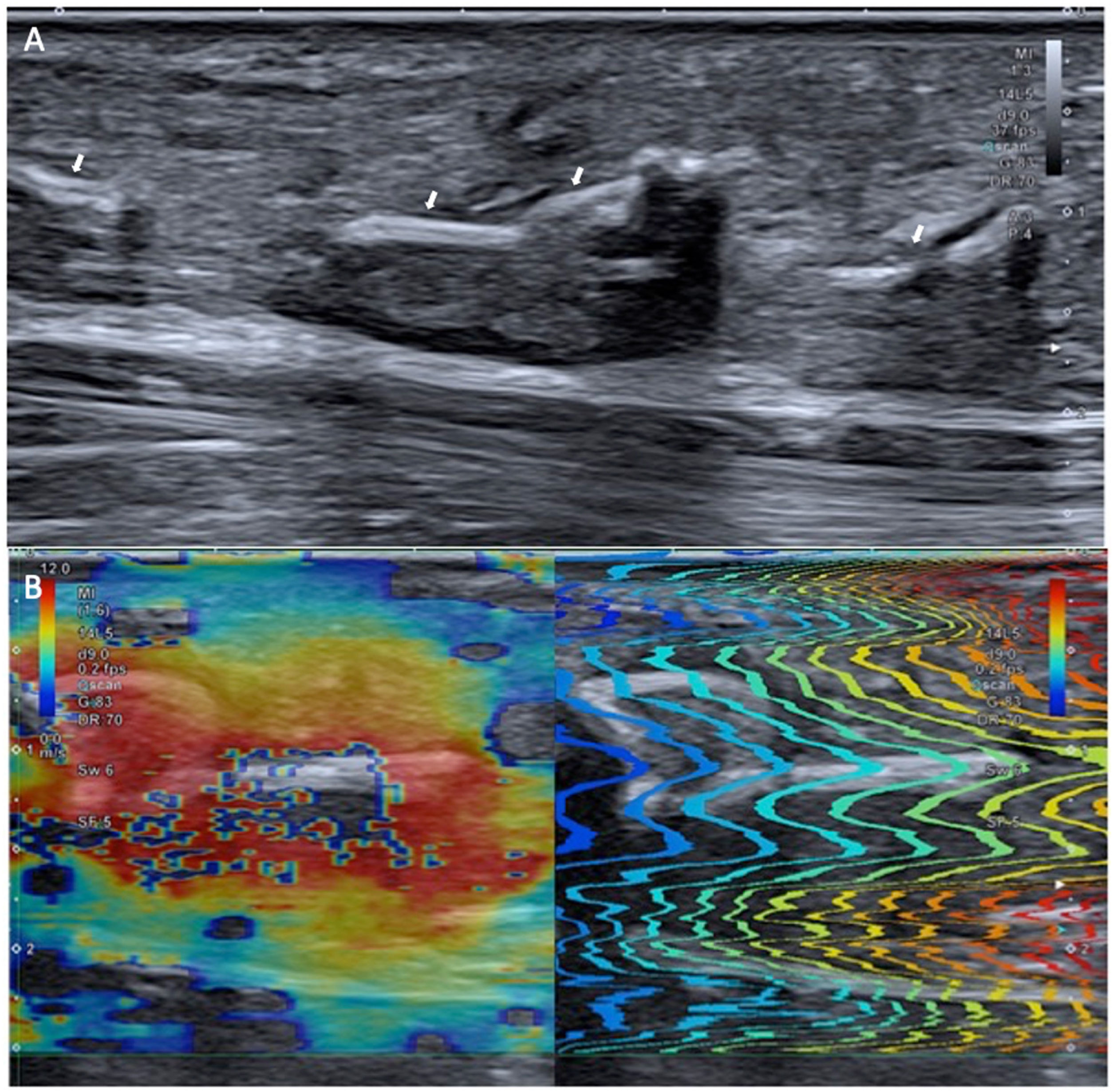

Other tendonsWhat we have described above is applicable to any tendon, taking the difficulties that the situation, trajectory or location may pose into account. At times, their deep location hampers a good ultrasound assessment and also limits the dynamic assessment (compression). In this case, elastography can be of great help by detecting the area of lack of stiffness corresponding to a partial tear focus (Fig. 4).

Distal biceps tendinopathy with intrasubstance tear. A) The tendon shows engrossment and marked hypoechogenicity consistent with tendinopathy; however, given its depth, it is difficult to determine whether or not there are tear foci. B) Elastography (strain) shows a red area in the insertion area (soft in strain) indicating intrasubstance tear.

The use of elastography in muscle disorders has grown inexorably, as it permits the real-time dynamic assessment of muscle stiffness during movement to detect abnormalities before they are visible with conventional imaging techniques. Its role in the assessment of muscle spasticity (stroke, spinal cord injury, myopathies, etc.), muscle tears and myofascial pain has already been described12.

Within the heterogeneity of the tissues which make up the musculoskeletal system, muscle is remarkably heterogeneous. Muscle fibres are surrounded by endomysium, arranged in fascicles, surrounded by perimysium, grouped in muscle bellies, surrounded by epimysium, and crossed in turn by nerves and vessels; the latter significantly affect muscle elasticity10.

Elasticity is influenced by the type of muscle, location, individual characteristics (for example, physical activity, obesity, gender, age, etc.) and, as with tendons, measurements vary depending on whether they are made in the short or the long axis.

Relaxed muscles present a soft-intermediate stiffness7 which increases as they contract. This correlates linearly with myoelectric activity, although a heterogeneous pattern is maintained, probably due to the asynchronous contraction of the different motor units28.

Different studies have described a decrease in stiffness in some myopathies, and an increase in others (Duchenne), as well as in spastic states secondary to stroke or cerebral palsy. This enables us to detect the most appropriate area in which to inject the botulinum toxin. This increased stiffness has also been described in “idiopathic” muscle pain or “cramp” (Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness [DOMS])10.

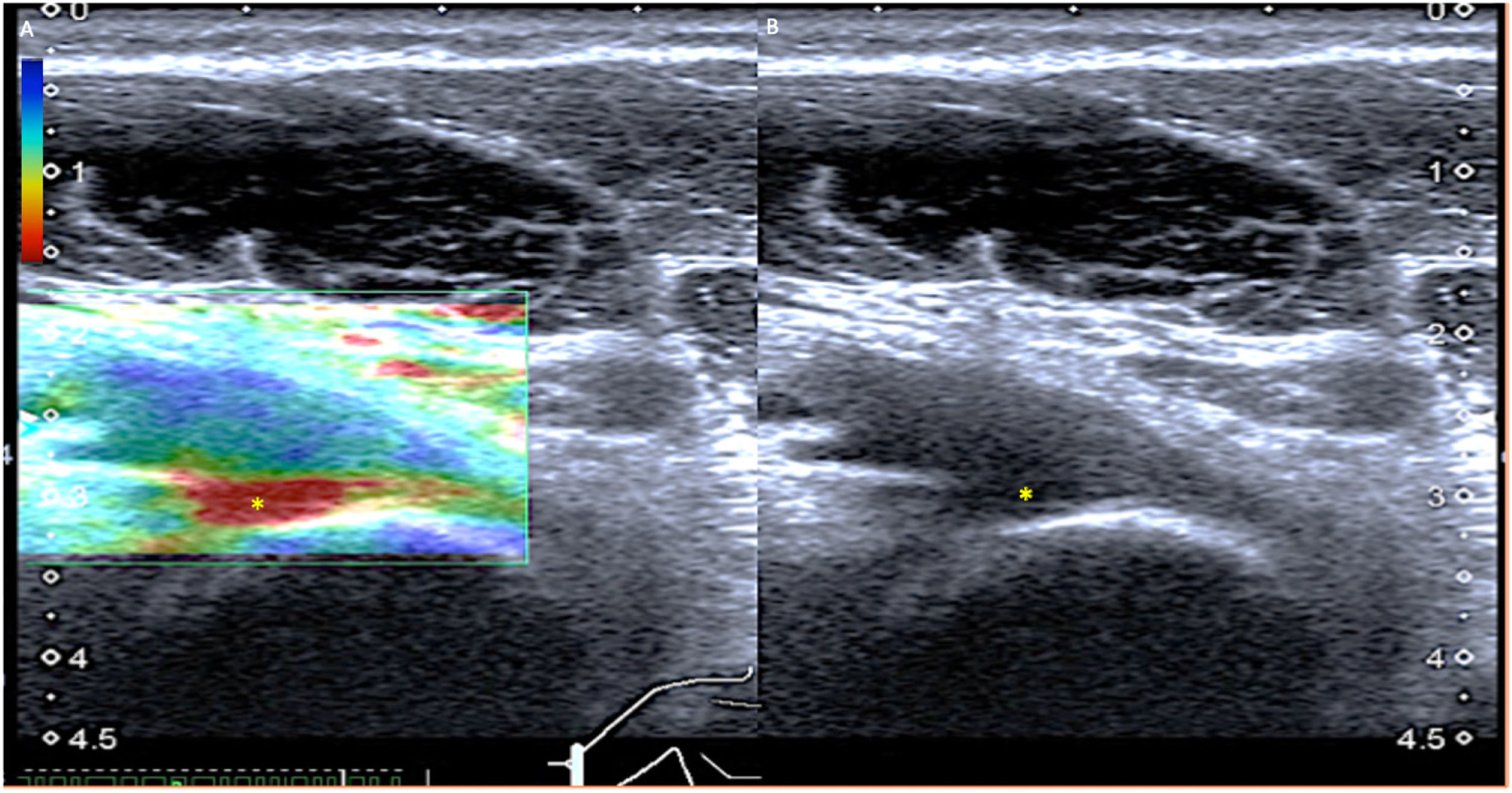

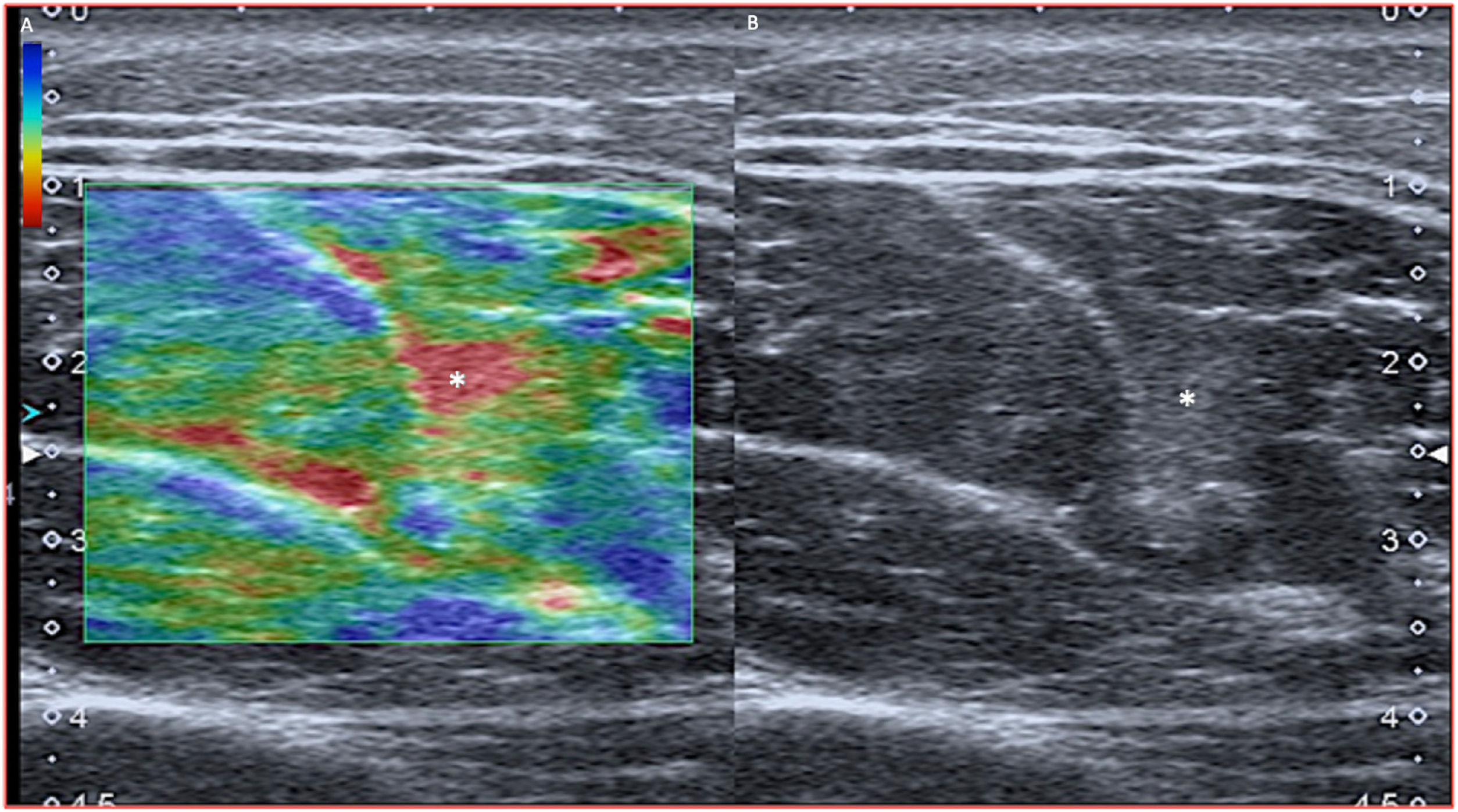

In our experience, muscle tears lead to a marked loss of stiffness, which is extremely useful when detecting incipient muscle lesions not clearly visible on ultrasound (Fig. 5). In addition, elastography also detects the progressive increase in stiffness that occurs in the healing of the lesion9, which is very useful when assessing both tissue repair and its possible complications (soft scar).

Ligaments and jointsAs the histology of the ligaments is quite similar to tendons, we can expect similar findings from the elastographic standpoint. Ligament tears will be detectable as soft areas within a normally stiff ligament.

Elastography has also been used in the study of rheumatic disease to assess the synovium1,19, although only a few studies have been carried out and it does not seem to contribute anything to the usual ultrasound scans.

Soft tissue massesElastography has also been suggested as a technique to determine whether a lesion is benign or malignant, based on its stiffness. In general, we would assume that a soft lesion is more likely to be benign than a hard one. However, this is not always the case, as it depends on other factors such as the bioelastic characteristics of the tissue and the location of the mass. Elastography therefore provides additional information in the assessment of the mass but should not be taken into account on its own29.

LimitationsAs a technique derived from ultrasound, elastography has the same limitations as ultrasound, such as operator dependency (for example, placement of the transducer, avoiding prior pressure, choosing the target area, etc.), in addition to its physical limitations (gas, calcium, obesity).

There are also limitations based on the tissue being studied, with the its heterogeneity and anatomical variability making it difficult to create reference values and establish protocols.

Future outlookThe most important challenge will be to overcome the limitations described, essentially reducing the dependence on the operator.

Indications and protocols need to be established.

Large-scale studies are called for to standardise these protocols and reference colour maps and measurement tables must be established.

We trust that this will improve with new technological advances; new types of elastography, 3D elastography, fusion with other techniques, etc.

Ten-point recommendations:

- 1

Obtain a good image in B mode8.

- 2

Apply the least possible pressure with the transducer (gel).

- 3

Position the transducer perpendicular to the skin surface.

- 4

Keep motion artifacts to a minimum.

- 5

Wait for the elastogram to stabilise.

- 6

Use the appropriate preset for the medium.

- 7

Place longitudinally to the structure (anisotropy).

- 8

Given the heterogeneity and the lack of reference values, it is preferable to be guided by colour maps.

- 9

When making measurements, it is preferable to measure speed (m/s), as elasticity (kPa) is obtained by multiplying it by density (ρ) and it is a heterogeneous tissue with variable density.

- 10

Use it whenever possible, correlating it with mode B and with the signs and symptoms, to improve our technique and progressively establish our own reference values.

We have to answer this question ourselves according to how we use it. One good example is the wheel, the discovery of which was a milestone in the advancement of Eurasian cultures, while in pre-Columbian America, although they were also aware of it, they only used it as a children's toy.

It is up to us to use the technique rigorously and seriously, establishing indications and protocols, applying it as a real tool, as a complement to ultrasound, instead of as a mere decoration for our ultrasound studies.

ConclusionsElastography is the greatest technical advance in ultrasound since the Doppler, and like the latter it is going to be another complementary tool.

The technique is still in the research phase, primarily in musculoskeletal imaging, and has yet to become a routine part of our day-to-day work in order for indications and protocols that determine its true role to be established.

It will be essential in the early diagnosis, prognosis, monitoring of treatment and follow-up of lesions.

It is, in short, a weapon loaded with future promise.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for study integrity: PGG

- 2

Conception of the study: PGG, SEM and ARMM

- 3

Study design: PGG

- 4

Data collection: PGG and SEM

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: PGG, SEM and ARMM

- 6

Statistical processing: No statistical processing was performed.

- 7

Literature search: PGG, SEM and ARMM

- 8

Drafting of the article: PGG

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: PGG, SEM and ARMM

- 10

Approval of the final version: PGG, SEM and ARMM

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.