Intrathyroidal ectopic thymic tissue (IETT) is an indulgent, unusual entity and is part of the differential diagnosis of thyroid nodules in the pediatric population. Because of the low prevalence of IETT, the diagnosis may be difficult. Awareness of this diagnosis is definitive to avoid surgical interventions. The aim of this study was to review the literature on the echographic characteristics of IETT. We conducted a search of Ovid, PubMed and the virtual health library.

A total of 619 patients with a mean age of 6.2 years old were included. IETT was located in the lower portion of both of the thyroidal lobes in 556 children, the echographic shape was reported for 173 patients, with the fusiform shape as the most representative, the appearance of the IETTs was reported for 121 patients, the most common was the hypoechogenic pattern with multiple internal echogenic foci. The average lesion diameter was 5.53 mm, and Doppler findings reported a hipovascular pattern in 56% of the lesions.

In conclusion, IETT is an infrequent entity; nonetheless, it must be considered in the differential diagnosis of neck nodules in children and should be study and follow with echography to avoid unnecessary surgery.

El tejido tímico ectópico intratiroideo (TTEI) es una entidad benigna y poco frecuente que se incluye en el diagnóstico diferencial de los nódulos tiroideos en la población pediátrica. Dada la baja prevalencia del TTEI, su diagnóstico puede resultar complejo, si bien es esencial para evitar posibles intervenciones quirúrgicas innecesarias. Este estudio tenía por objeto revisar la documentación médica sobre las características ecográficas del TTEI. Para ello, llevamos a cabo una búsqueda en Ovid, PubMed y la Biblioteca Virtual en Salud.

Se incluyó a un total de 619 pacientes con una edad media de 6,2 años. En 556 niños y adolescentes, el TTEI se localizó en la parte inferior de ambos lóbulos tiroideos. Se notificó la forma ecográfica en 173 pacientes, siendo la forma fusiforme la más representativa. El aspecto del TTEI se notificó en 121 pacientes, observándose un patrón hipoecogénico con múltiples focos ecogénicos en su interior. El diámetro medio de la lesión fue de 5,53 mm, y la ecografía Doppler indicó un patrón hipovascular en el 56% de las lesiones.

En conclusión, si bien el TTEI es una entidad poco frecuente, debe tenerse en cuenta en el diagnóstico diferencial de los nódulos del cuello en la población pediátrica y debe estudiarse y seguirse mediante ecografía a fin de evitar una intervención quirúrgica innecesaria.

Thyroid nodules are not very prevalent in children (0.2%–2%), but the risk of malignancy is greater than in adults1; thyroid cancer accounts for 4% of pediatric and adolescent malignant tumors.2,3 Thyroid ultrasonography is widely used in the study of suspicious lesions in the thyroid glands because it is noninvasive and avoids the use of ionizing radiation.2,4 As its use continues to increase, more nodules are being found, such as simple colloid or hemorrhagic cysts, intrathyroidal parathyroid gland and follicular adenomas and intrathyroidal ectopic thymic tissue.4–6 Unlike in adults, in children all thyroid nodules with suspicious ultrasound characteristics should be studied with fine needle aspiration biopsy regardless of the size.1

Intrathyroidal ectopic thymic tissue (IETT) is an unusual cause of thyroid nodules in children, with an incidence of less than 1%.7 In most cases, it is diagnosed in a surgical specimen after an intervention due to the findings in Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) sometimes are not specific.8,9 This entity represents a challenge in the differential diagnosis of thyroid masses3 which are difficult to diagnose echographically if IETT is not taken into consideration. The aim of this article was to review the literature on the most common echographic characteristics of IETT.

MethodsLiterature searchThe PRISMA guidelines were followed during the data extraction, analysis and report.10 The search was done using the following databases: Ovid, PubMed, and the virtual library of health (VLH), which includes BIREME, LILACS and many other Latin American sources. No limits were imposed of time of publication in the search. The search was carried out in June 2021. Documents available in English and Spanish were considered. The search was done with the following MeSH terms (Medical Subject Headings) in Pubmed and Ovid: Thyroid Gland AND Thymus Gland AND Child AND Ultrasonography. Each MeSH term was translated into DeCS (Health Sciences Descriptors) to explore sources of information in Spanish and English through the VLH.

Selection of studies, data extraction and quality evaluationInclusion criteria for the systematic review were the following: (a) studies as cross-sectional studies, case series, analytic studies (case and control studies or cohort studies) or diagnostic test studies. (b) Studies where the presence of intrathyroidal thymic was evaluated by echography. Studies without information of echographic findings (size or shape or location) were excluded. Three authors independently screened all the titles and abstracts from the publications performed an eligibility assessment. The recovered articles were rejected if they did not meet the eligibility criteria. The data extracted from each article included the author’s name, year of publication, study design, IETT diagnosis, other diagnoses, age, sex, maximum lesion diameter, intrathyroidal localization by echography, lesion shape by echography, and Doppler findings of the lesion. The quality of the articles was evaluated by two authors independently from the selected studies by applying the Joanna Briggs Institute evidence level checklist (JBI).11

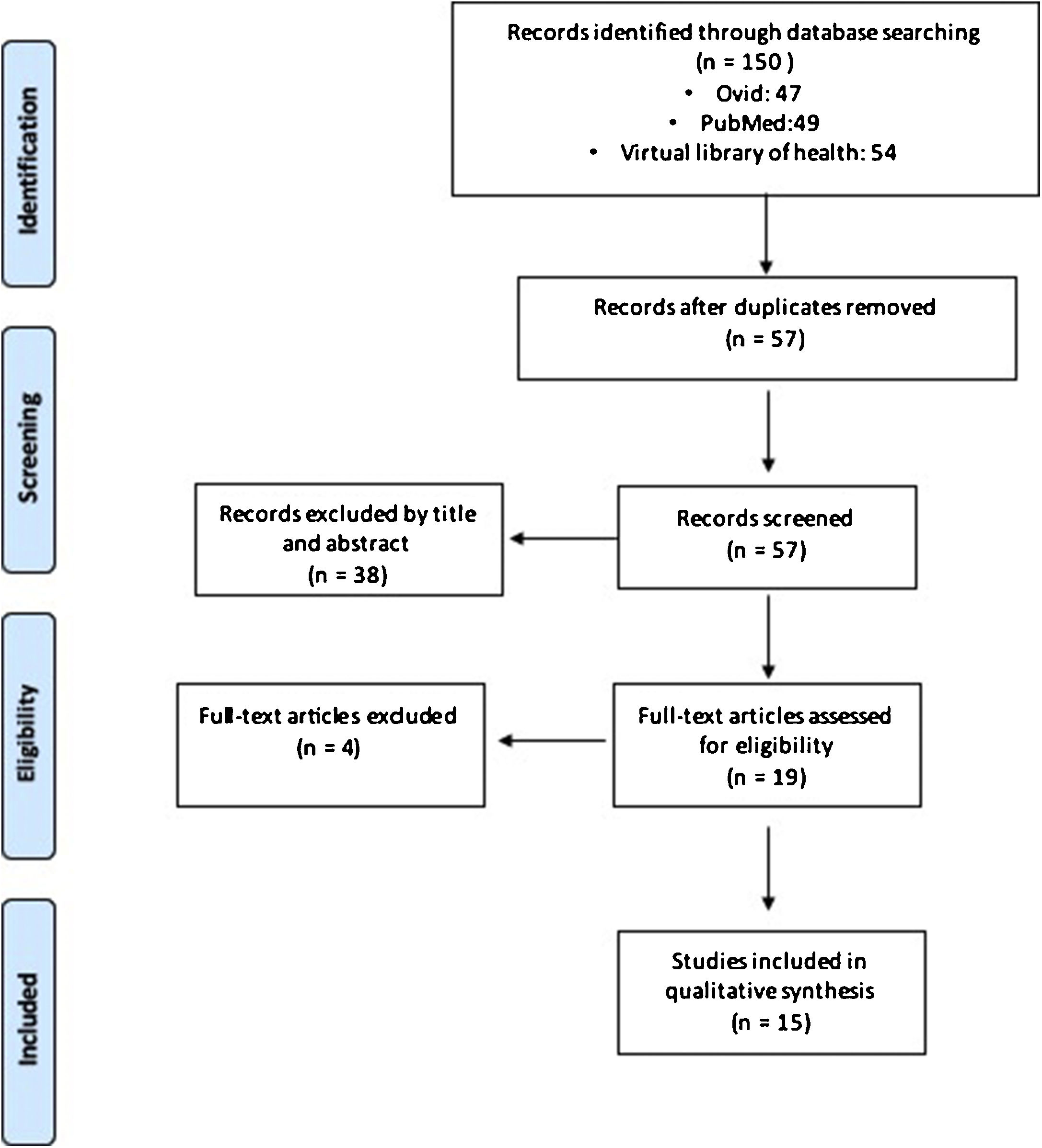

ResultsStudy selectionA total of 150 articles were identified: 47 in Ovid, 49 in PubMed, and 54 in the virtual library of health. Of these, 93 were duplicate studies. Titles and abstracts of 57 articles were reviewed to determine if they met the eligibility criteria. Finally, 15 studies evaluated the presence of intrathyroidal thymic by echography.2–6,12–21 14 articles were cross-sectional studies and only one article included case series.4 The flow diagram for the systematic selection of the literature and the inclusion of articles in the analysis is shown in Fig. 1. Quality of the evidence is shown in supplementary material 1.

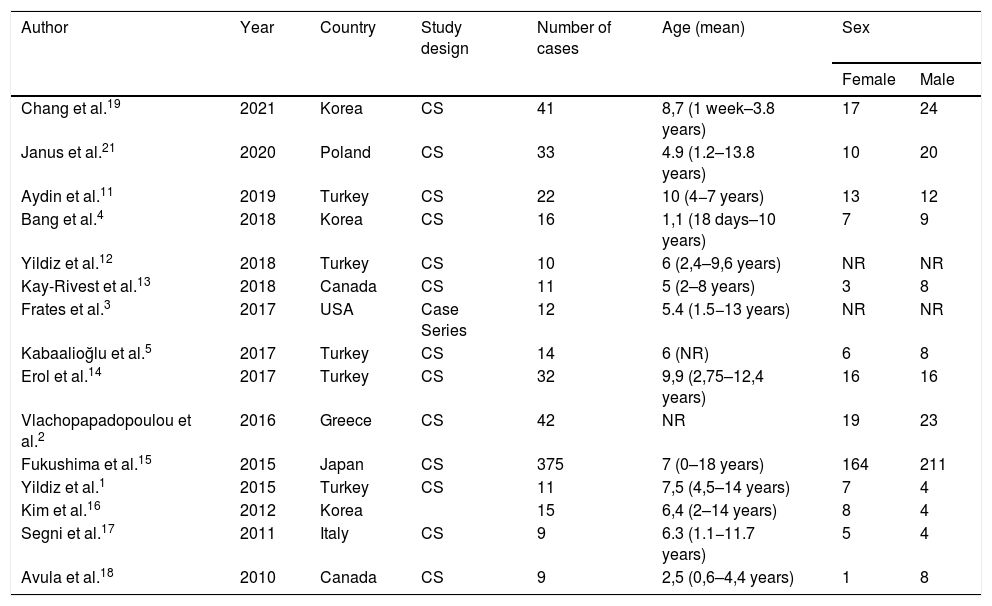

Patients and studies characteristicsThe demographic characteristics of the patients from the 15 articles are reported in Table 1. In total, 652 patients were included, the lesion were more common amongst male 351 vs 276 female, two studies with 25 patients don’t included the gender.3,12 The mean age was 6.19 years (range 0–18 years), one article don’t reported the mean age.2

Demographic information of articles included.

| Author | Year | Country | Study design | Number of cases | Age (mean) | Sex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | ||||||

| Chang et al.19 | 2021 | Korea | CS | 41 | 8,7 (1 week–3.8 years) | 17 | 24 |

| Janus et al.21 | 2020 | Poland | CS | 33 | 4.9 (1.2–13.8 years) | 10 | 20 |

| Aydin et al.11 | 2019 | Turkey | CS | 22 | 10 (4−7 years) | 13 | 12 |

| Bang et al.4 | 2018 | Korea | CS | 16 | 1,1 (18 days–10 years) | 7 | 9 |

| Yildiz et al.12 | 2018 | Turkey | CS | 10 | 6 (2,4–9,6 years) | NR | NR |

| Kay-Rivest et al.13 | 2018 | Canada | CS | 11 | 5 (2–8 years) | 3 | 8 |

| Frates et al.3 | 2017 | USA | Case Series | 12 | 5.4 (1.5−13 years) | NR | NR |

| Kabaalioğlu et al.5 | 2017 | Turkey | CS | 14 | 6 (NR) | 6 | 8 |

| Erol et al.14 | 2017 | Turkey | CS | 32 | 9,9 (2,75–12,4 years) | 16 | 16 |

| Vlachopapadopoulou et al.2 | 2016 | Greece | CS | 42 | NR | 19 | 23 |

| Fukushima et al.15 | 2015 | Japan | CS | 375 | 7 (0–18 years) | 164 | 211 |

| Yildiz et al.1 | 2015 | Turkey | CS | 11 | 7,5 (4,5–14 years) | 7 | 4 |

| Kim et al.16 | 2012 | Korea | 15 | 6,4 (2–14 years) | 8 | 4 | |

| Segni et al.17 | 2011 | Italy | CS | 9 | 6.3 (1.1−11.7 years) | 5 | 4 |

| Avula et al.18 | 2010 | Canada | CS | 9 | 2,5 (0,6–4,4 years) | 1 | 8 |

CS: Cross-sectional; NR: not reported.

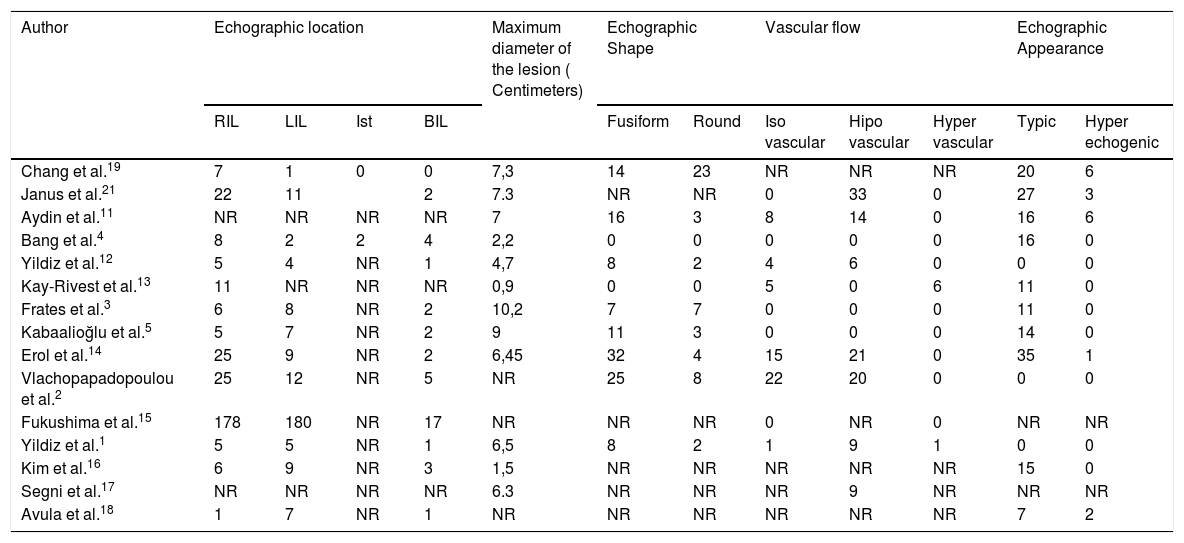

The intrathyroidal localization was described for 600 IETS. For 99,6% (n = 598) of the patients, IETT was located in the lower portion of the thyroid gland. Of those, ultrasonography showed 42,4% located in the left lobe (n = 254), 50,8% in the right lobe (n = 304) and 6.6% bilaterally (n = 40). The echographic shape of the lesion was reported for 173 patients. Fusiform was the most representative shape (69.9%, n = 121), followed by rounded (30%, n = 52). For 159 patients, Doppler ultrasonography findings were reported. Of those, 64% of IETTs presented with hipovascularization (n = 103), 34% demonstrated the same vascular activity as the adjacent thyroid tissue (n = 55), and the remaining 4,4% showed hypervascularization (n = 7). Nine studies, with a total of 190 patients, described the echographic appearance of IETTs. The typical appearance was defined as hypoechogenic with multiple untargeted internal echogenic foci that resembled the ectopic thymus tissue. This appearance was present in 90,5% (n = 172) of patients, while only 9.4% documented a hyperechogenic appearance (n = 18). The diameter of the lesions was 5,73 mm on average, with a range of 0,9 to 10,2 mm (Table 2).

Echographic characteristics.

| Author | Echographic location | Maximum diameter of the lesion ( Centimeters) | Echographic Shape | Vascular flow | Echographic Appearance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIL | LIL | Ist | BIL | Fusiform | Round | Iso vascular | Hipo vascular | Hyper vascular | Typic | Hyper echogenic | ||

| Chang et al.19 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7,3 | 14 | 23 | NR | NR | NR | 20 | 6 |

| Janus et al.21 | 22 | 11 | 2 | 7.3 | NR | NR | 0 | 33 | 0 | 27 | 3 | |

| Aydin et al.11 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 7 | 16 | 3 | 8 | 14 | 0 | 16 | 6 |

| Bang et al.4 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2,2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| Yildiz et al.12 | 5 | 4 | NR | 1 | 4,7 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kay-Rivest et al.13 | 11 | NR | NR | NR | 0,9 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 6 | 11 | 0 |

| Frates et al.3 | 6 | 8 | NR | 2 | 10,2 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 |

| Kabaalioğlu et al.5 | 5 | 7 | NR | 2 | 9 | 11 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 |

| Erol et al.14 | 25 | 9 | NR | 2 | 6,45 | 32 | 4 | 15 | 21 | 0 | 35 | 1 |

| Vlachopapadopoulou et al.2 | 25 | 12 | NR | 5 | NR | 25 | 8 | 22 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fukushima et al.15 | 178 | 180 | NR | 17 | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | 0 | NR | NR |

| Yildiz et al.1 | 5 | 5 | NR | 1 | 6,5 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Kim et al.16 | 6 | 9 | NR | 3 | 1,5 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 15 | 0 |

| Segni et al.17 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 6.3 | NR | NR | NR | 9 | NR | NR | NR |

| Avula et al.18 | 1 | 7 | NR | 1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 7 | 2 |

NR: Not Reported; RIL: right inferior lobe; LIL: left inferior lobe, Ist: Isthmus.

We present the first systematic review of echographic findings in IEET in children. IETT can be recognized as a single lesion or together with the presence of associated thyroid nodules, which may lead to a diagnosis of a suspicious mass in children.6 In total was included 652 patients of IETT, most of them were located in the lower part of the thyroid lobes (99.6%). This finding is particularly relevant and it’s important for the radiologist to be aware of it at the moment of the study. This is because of the embryological development of the pharyngeal apparatus: Embryologically, the thymus develops from the third pharyngeal pouch, and its development occurs near the thyroid gland, which develops from the fourth pouch.3 Towards the sixth week, the thymic primordium is located medially and forms the thymus between the seventh and eighth weeks; in turn, the thyroid gland develops and becomes localized in front of the cricoid cartilage, and the thymus elongates in a tubular fashion, losing its connection with the pharynx. Later, it migrates caudally to the superior mediastinum; during this displacement, remnant thymic tissue can appear anywhere along the path. The presence of this remnant tissue has been reported in the pharynx, trachea, esophagus and mediastinum.18 The IETT is derived from the abnormal migration of the tissue between the eighth and ninth embryonic weeks after it becomes trapped when crossing the thyroid gland.4

The mean age across the studies was 6,19 years with a range of 0–18 years. The typical age of presentation is before ten years old, and involution presents before puberty.4,5,21 This entity don’t present symptoms, and the ultrasonographic diagnosis is usually incidental as described in the literature.4,5 Janus et al. with a mean time of follow-up of 76,5 months, report the complete regression of the lesion in 12 of the 30 patients.21 Kay-Rivest et al. demonstrated an interval size stability after 36 months14 Erol at al. with a mean of 22,6 months, report no statistically difference between the measures.15 Segni et al. after a mean of 34 months only three lesions presented changes in its measurements.18 Kabaalioğlu et al. after 33 months follow-up reported, in 1 the lesion had disappeared, in 4 it had decreased in size, and in 1 it had grown in size.6 This findings reinforce the possibility of ultrasonographical follow-up, without compromising the safety of the patient, this because, as children grow older and their immune systems mature, the thymus is replaced by fatty tissue, and physiological involution occurs.4

On ultrasonography IETT has very distinctive appearance known as the typical pattern; it was observed in 90,6% of the exams.2,4,6,15,18,22 The presence of internal focal echogenicity in this pattern can imitate the presence of microcalcifications, which are often highly suspicious of papillary thyroid carcinoma, and must not be considered as an isolated finding, since in the case of thymic tissue, they correspond to the presence of Hassall corpuscles.12,20 This distinctive appearance added to the absence of lymphadenopathy, rules out malignancy and should alert the radiologist about the presence of IETT.9 The fusiform shape is a reliable parameter for distinguishing IETT lesions, this is consistent with our findings; 69,1% of patients showed this shape.13,15,18

In the Doppler echo exam, when compared with that of the adjacent thyroid parenchyma, the vascularization of the lesion can be hypo-, hyper- or isovascular.18 The IETT is hipovascular in most of the grouped data, showing poor flow with respect to the rest of the gland.18 Interestingly, the only author that described a different result was Segni, who did not find any vascularization.18 It is important to take this finding into further consideration when the initial suspicion includes a differential diagnosis of thyroiditis and malignant lymph node or thyroid neoplasia, where the vascular activity tends to be much more notable due to the activity of the gland.9

Four studies performed FNAC in worrisome nodules; all revealing abundant lymphoid stroma and cells of different sizes, where Hassall corpuscles were rarely observe.4,14,21,23 Yildiz et al. reported 3 FNAC: one as Hashimoto thyroiditis and two as lymphoma.23 The diagnose of IETT on a surgical specimen, is reported in one patient of the study of Janus et al. who went to a hemithyroidectomy by parents decision.21 Kay-Rivest report one patient who underwent to hemithyroidectomy due to the lesion occupied more than 50% of the thyroid lobule.14 And Yildiz report one hemithyroidectomy for a patient with congenital adrenal hyperplasia.2 This means the surgical treatment should be reserve for specific cases, to rule out malignancy when certain echographic characteristics raise suspicions of a malignant nodule.

We would like to acknowledge the limitations of our study First, the age of the population varies severely, this because even if the usual age of presentation is before ten years old, in some studies are included patients older than that. Second, due to the rarity of this entity we had a small number of cases, and because the benign course of the IETT many patients are lost to follow up, so. Finally, the definitive diagnose cannot be certain without a biopsy, which in this case can be ignored if ultrasound features suggest IETT.

ConclusionIn conclusion, we consider that after reviewing the available literature, despite the rarity of IETT, in the pediatric population, it must be considered in the differential diagnosis of thyroid nodules. The echographic findings that are most commonly observed are a fusiform shape, a hypoechoic appearance, a size under 10 mm for the longest axis and localization in the lower part of one or both thyroid lobes. These echographic findings, together with a highly cellular FNAC presenting with lymphocytes, should make the clinician reconsider the surgical treatment for the patient. With echographic controls, the clinical outcome of these patients is safe without having to perform surgical extirpation of the gland due to the presence of IETT.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for study integrity: JG, MM, RPM

- 2.

Study conception: JG,MM, RPM

- 3.

Study design: RPM

- 4.

Data acquisition: JG, RPM

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: JG, RPM

- 6.

Statistical processing: RPM

- 7.

Literature search: JG, RPM

- 8.

Drafting of the manuscript: JG, RPM

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually sig-nificant contributions: JG, RPM

- 10.

Approval of the final version: JG, RPM

None declared by the authors.

Please cite this article as: Gómez-Herrera J, Melo-Uribe MA, Parra-Medina R. Hallazgos ecográficos en el tejido tímico ectópico intratiroideo en niños y adolescentes. Una revisión sistemática. Radiología. 2021;63:512–518.