Massive pulmonary embolism (PE) is a disease with high mortality, therefore early diagnosis and treatment is essential to save lives. In the absence of contraindications, patients with massive PE (high risk) should be treated immediately with full-dose intravenous systemic thrombolysis. The subset of patients for whom systemic thrombolysis is not successful and who continue to present with haemodynamic compromise or those with contraindications may be candidates for various catheter-directed or surgical therapies. The decision algorithm in intermediate-high/submassive risk patients is complex and must be employed by a multidisciplinary team and success may depend on the experience of the medical specialists involved.

El tromboembolismo pulmonar (TEP) masivo es una enfermedad con una alta mortalidad, por tanto el diagnóstico y tratamiento oportuno es esencial para salvar vidas. En ausencia de contraindicaciones, los pacientes con TEP masivo (alto riesgo) deben ser tratados inmediatamente con trombolisis sistémica intravenosa en dosis completa. El subconjunto de pacientes en los que fracasa la trombolisis sistémica con compromiso hemodinámico continuo o aquellos con contraindicaciones pueden ser candidatos para diversas terapias dirigidas por catéter o quirúrgicas. El algoritmo de decisión en los pacientes de riesgo intermedio-alto / submasivo es complejo y debe contar con la ayuda de un enfoque basado en un equipo multidisciplinar y dependerá de la experiencia del equipo local.

Venous thromboembolic disease (VTE) is the third most common cardiovascular disease, with an average annual incidence of 100–200 cases per 100,000 population. VTE includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), with PE being the most severe form. Pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) is the leading cause of preventable death in hospitalised patients.1

The epidemiology is difficult to establish as it can be asymptomatic and an incidental finding, while in other cases it may manifest as sudden death (Fig. 1). The high incidence2,3 is accompanied by a high mortality rate, with a significant impact on medical care and healthcare expenditure.4

The mortality rate in the first three months is 15–18% and almost half of these deaths are directly attributed to PTE. Massive PE, characterised by "haemodynamic instability", has an incidence of 4.5% and the mortality rate exceeds 58%, with most deaths occurring within the first hour.5

Therapeutic management in the high- and intermediate-risk patient (right ventricular [RV] dysfunction and positive myocardial damage markers) is not clearly defined.6 Fibrinolytic therapy has shown haemodynamic repercussions and significant bleeding, with an improvement in the PTE-related mortality rate, prompting the search for new therapeutic alternatives with fewer side effects. Since 2014, thrombectomy by percutaneous catheter-directed aspiration of the pulmonary arteries has been established as an alternative to surgical embolectomy, with the aim of improving RV afterload, clinical symptoms and the survival of patients with PTE, applying different therapeutic approaches.7,8 This measure is of great relevance, especially in the subject with contraindications to systemic fibrinolysis or as a rescue for failed fibrinolysis.

After the acute episode of PE, resolution of pulmonary thrombi is often incomplete, with lung perfusion studies demonstrating abnormalities in up to 30% of patients one year after the acute episode.9–11 The incidence of chronic pulmonary hypertension following PE is currently estimated to be approximately 1.5%, with the majority of cases occurring within 24 months of the recorded episode.12,13

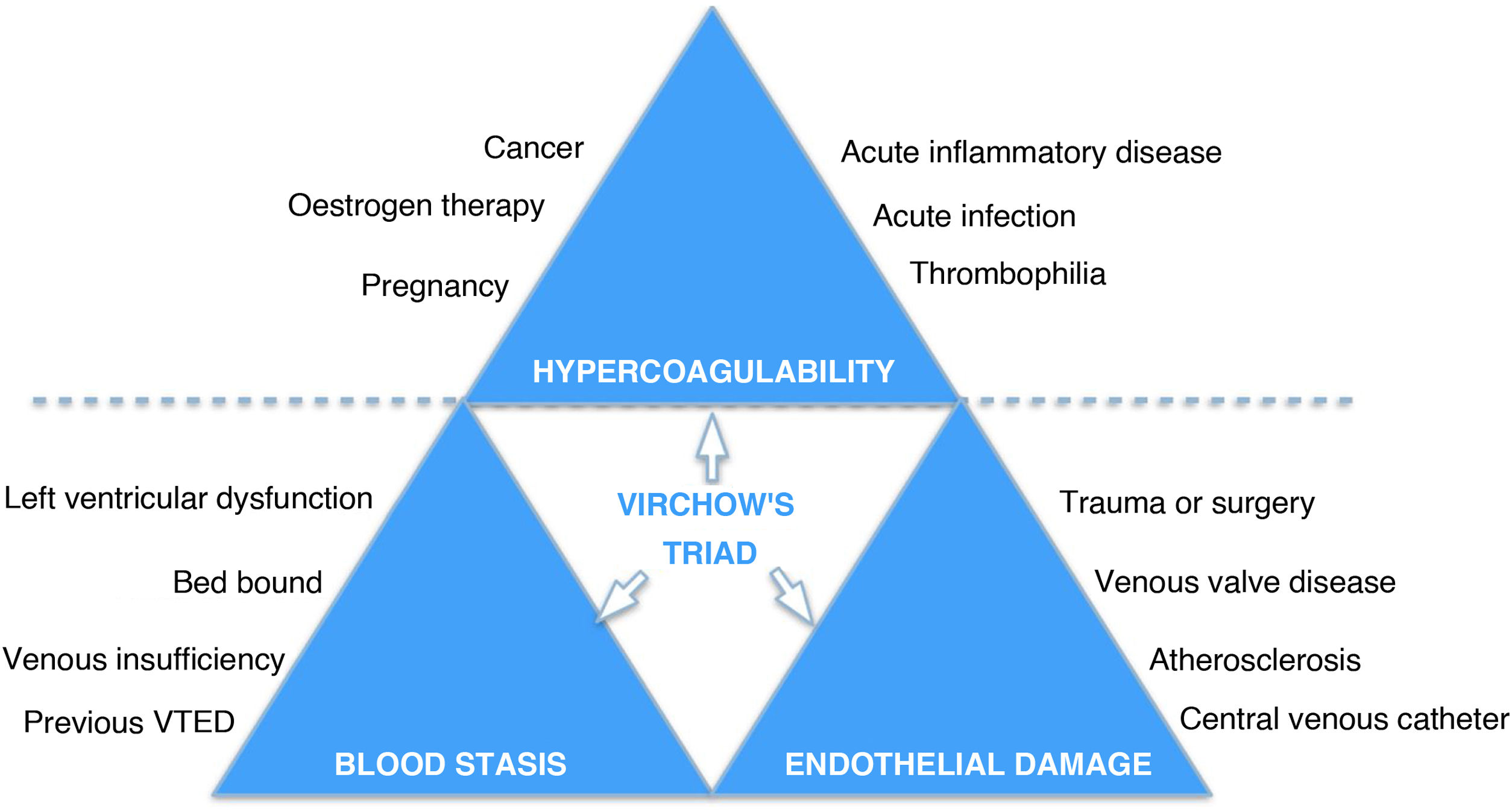

Pathophysiology of pulmonary thromboembolismThe pathophysiology of acute PTE is complex, including vascular obstruction, acute inflammation and vasospasm; and in chronic pulmonary embolism there are also changes in pulmonary vasculature. In the acute phase, pulmonary arterial obstruction causes RV overload and increased RV pressure, leading to RV dysfunction and failure, with impaired gaseous exchange and systemic hypoxia. Anatomical obstruction and hypoxia are two separate problems, and they trigger an inflammatory cascade, arterial damage and vasoconstruction due to the release of potent vasoconstrictor substances such as thromboxane A2 and serotonin. These factors have a greater vascular effect with age, obesity, immobility, surgical procedures, thrombophilic states, smoking, being female, cancer and contraceptive use14 (Fig. 2).

Management of PTE is based on the severity of haemodynamic status with cardiac and respiratory consequences. There is a wide spectrum of symptoms associated with acute PTE, ranging from patients being asymptomatic to sudden death. Those who survive cardiorespiratory arrest or cardiogenic shock with hypotension account for approximately 3% of all cases and are considered to have high-risk acute PTE (massive PTE). The definition of massive PTE is clinical and relates to sustained arterial hypotension and/or haemodynamic instability, but in no case to thrombotic burden. These patients require immediate reperfusion to reduce morbidity and mortality risk. In contrast, almost 40% have low-risk PTE defined by limited symptoms, absence of haemodynamic instability or respiratory compromise, lack of comorbidities and absence of RV overload. The morbidity and mortality rates associated with low-risk acute PTE are minimal and therefore management is conservative with the administration of anticoagulants.15

However, most patients with acute PTE fall somewhere between these two extremes, in the intermediate risk category (termed "submassive" by the American Heart Association [AHA]). This group of subjects do not have systemic hypotension, but show at least one sign of right ventricular dysfunction.

Clinical practice guidelines distinguish between two subgroups within this category: 1) patients with acute PTE without haemodynamic instability who show evidence of RV overload on imaging and biomarker elevation, classified as intermediate-high risk (Fig. 2); 2) patients showing a single sign of RV dysfunction (biomarker or imaging test), or no sign, but associated with a pulmonary embolism severity index (PESI) of 3 or simplified PESI (sPESI) >0, classified as low-intermediate risk patients.6

Most risk stratification algorithms use multiple parameters to assess RV overload. Levels of biomarkers, such as troponin, B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal proBNP (NT-proBNP) provide evidence of myocardial injury. Echocardiography is used to assess global RV dilation and local systolic dysfunction, tricuspid valve regurgitation and paradoxical motion of the interventricular septum and for measurement of pulmonary artery blood pressure. Computed tomography angiography (CT angio) allows assessment of pulmonary arterial branch involvement (Miller's index calculation) and estimation of the RV/left ventricle (LV) ratio. CT angiography is essential in all cases to plan the intervention.16

Three scientific societies (AHA, American College of Chest Physicians and European Society of Cardiology) included risk assessment related to acute PTE in their guidelines, based primarily on haemodynamic instability and RV dysfunction17–19 (Table 1).

PESI for the calculation of risk stratification in PTE.

| Variables | Original PESI | Simplified PESI |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Age in years | (>80) + 1 |

| Being male | 10 | |

| Altered mental state | 60 | |

| History of cancer | 30 | 1 |

| History of heart failure | 10 | 1a |

| COPD | 10 | |

| TEMP <36° | 20 | |

| Heart rate ≥ 110 BPM | 20 | 1 |

| Systolic pressure < 100 mmHg | 30 | |

| Respiratory rate ≥ 30 RESP/min | 20 | |

| Oxyhaemoglobin saturation < 90% | 20 | 1 |

| Risk classification | Very low (≤65) | |

| Low (66−85) | Low (0) | |

| Intermediate (86−105) | ||

| High (106−125) | High (≥1) | |

| Very high (>125) |

PESI: pulmonary embolism severity index; PTE: pulmonary thromboembolism.

All-cause mortality from intermediate-risk acute PTE is approximately 1.9–2.9% at seven days, 4.9–6.6% at 30 days and 14.5% at 90 days.20,21 The randomised PEITHO study involving more than 1000 patients with acute intermediate-high risk PTE reported a mortality rate of approximately 1.5% at seven days and 2.8% at 30 days.22 These estimated mortality rates have a significant impact on the decision algorithm because invasive methods can be associated with risks to the patient. In general, the positive predictive value of right ventricular overload alone is insufficient to predict haemodynamic deterioration and justify invasive management of all intermediate risks.3

However, some patients with intermediate risk PTE may require urgent measures to restore haemodynamic stability, as about 10% of those who are normotensive and have RV overload decompensate suddenly.23 Unfortunately, we still do not have predictive factors to help identify these patients and further research is needed.23 The use of risk stratification markers, such as right ventricular dysfunction according to transthoracic echocardiography/chest CT-angiography, tachycardia, hypoxia and specific biomarker cut-off values, could be useful for predicting adverse effects in both males and females.6,20,22

The gold standard treatment for acute massive PTE has traditionally been systemic thrombolysis, but this is associated with a significant increase in the risk of major and intracranial haemorrhage,9 making endovascular treatment preferable in certain scenarios.

Massive acute PTE (high risk) is defined as acute PTE in the setting of sustained hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg for at least 15 min or requiring inotropic support), no pulse or persistent profound bradycardia (heart rate <40 bpm with signs or symptoms of shock).24 Clinical symptoms that may suggest hypotension include syncope, dizziness, diaphoresis and anxiety. The patient may also be hypoxic and have dyspnoea, chest pain or nausea; nausea may suggest liver congestion secondary to right heart failure. Subjects typically present with shock and cardiac arrest and are in Intensive Care Units or en route to these with vasopressors and/or respiratory support.

Although ventilatory support is often required, intubation should be postponed if possible, as it may raise pulmonary artery pressure, decrease cardiac preload and exacerbate overload.18,25

Systemic thrombolysis is a particularly attractive option for these patients, as it offers a fast and effective solution to resolve the acute clot. Regardless of the patient's risk stratification, unless there is a contraindication to anticoagulation, therapeutic doses of unfractionated heparin should be administered immediately until further intervention can be performed. The AHA does not routinely recommend co-administration of heparin with thrombolytics.18 However, no randomised trials comparing concurrent anticoagulation and thrombolysis with maintaining anticoagulation during thrombolysis have been conducted.

Endovascular treatment in acute pulmonary thromboembolismThe existence of a multidisciplinary group in the management of PTE facilitates coordinated therapeutic decisions affecting patient survival, a strategy now known in many centres as "PTE code". Due to the variety of clinical scenarios in which there is no clear evidence on the best treatment, consensus decisions involving expert specialists in areas such as cardiology, respiratory medicine, critical care, anaesthetics and radiology-interventional radiology are essential; in addition to the increasingly sophisticated therapies for these patients with requirements for specialised and trained staff, ideally available 24/7.26,27

TechniqueThe procedure should be performed in a digital subtraction angiography suite, with the occasional application of contrast-enhanced cone-beam CT, creating a high-resolution three-dimensional image of the pulmonary vascular system, which can provide immediate guidance for therapeutic intervention.

Vascular access is by puncture of the common femoral vein or right internal jugular vein using the standard Seldinger technique with placement of appropriate introducer sheath (5–10 French), although some devices require up to 24 French.28

Direct transcatheter pulmonary pressure measurement is performed prior to initiating thrombus lysis/aspiration to provide a baseline record to guide the procedure. Increased pulmonary pressure could trigger complications in these patients, such as arrhythmias secondary to acute RV overload.

Non-selective angiography by iodinated contrast injection is performed in the main pulmonary artery, with flow less than 8 cc/s and a volume of 12–15 cc, in an anteroposterior view, in order to assess the anatomy and demonstrate filling defects for targeted treatments. If necessary, selective right and left angiographic studies in oblique views will be performed to determine the true extent of acute PTE and pulmonary perfusion.

Catheter-directed thrombolysisWith the patient systemically heparinised, as an initial step the thrombus can be lysed by placing a catheter (pig tailtype) over a hydrophilic guide into the thrombus and then manually rotating the catheter to unblock major arteries and increase the surface area of the thrombus for endogenous or exogenous thrombolysis to take place (Table 2). Using a selective catheter and a hydrophilic guidewire, the pulmonary artery with the highest thrombus burden is redirected first. The dose used is much lower than in peripheral administration and therefore its systemic fibrinolytic effect is very low. A routinely used diagnostic angiography catheter or a specific multi-lumen catheter can be used to increase the concentration of the lytic agent. For thrombolysis, bilateral femoral access is required with placement of catheters with multiple holes (5 or 10 cm infusion length) in the right and left arteries, with the catheters being threaded into the thrombus. A bolus of 5 mg alteplase (rTPA-Actilyse®, Biberach/Riss Germany) is administered into the thrombus, followed by an infusion of 0.5–1 mg rTPA per hour into each catheter and a slow infusion of heparin into the sheath side valve to maintain patency of the sheath, with significantly superior improvement in RV function compared to patients treated with anticoagulation alone.29 If choosing fibrinolysis via ultrasound-assisted catheters (infusion lengths of 6 or 12 cm) using a multi-perforated catheter system (EkoSonic Endovascular System [EKOS] Corp., Boston Scientific Marlborough, MA, USA), shorter periods of thrombolysis and smaller doses of rTPA may be sufficient. The infusion usually lasts 12−24 h, so the average total dose is 20−28 mg. Efficient systemic administration of heparin is continued throughout the endovascular fibrinolysis procedure. The use of other thrombolytic agents such as urokinase is also described in the literature. The patient is transferred to an Intensive Care Unit for follow-up and strict monitoring. Several comprehensive cost-benefit studies have been conducted, such as the RESCUE study,30 and results showed that major bleeding complications are lower with catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT) than with systemic thrombolysis.31,32

Devices most commonly used in the treatment of acute PTE.

| Devices | |

|---|---|

| Endovascular thrombolysis | |

| CDT | Uni-fuse® (Angiodynamics, Latham, NY, USA). |

| Cragg-MacNamara (Ev3 Endovascular) | |

| Ultrasound-accelerated thrombolysis | EkoSonic® (EKOS, Boston Scientific, USA). |

| Mechanical thrombectomy | |

| Thrombus fragmentation | Pig tail catheter |

| Balloon angioplasty | |

| Direct thrombus aspiration | Manual suction with long introducer sheath and removable haemostatic valve |

| Angio Vac® Aspiration System (Angiodynamics, Latham, NY, USA). | |

| 22 French catheter with cardiopulmonary bypass | |

| Rotational thrombectomy | Aspirex thrombectomy (Abbott, Chicago, USA). |

| Rotational thrombectomy with motorised guidance | Cleaner® Rotational Thrombectomy System (Argon Medical devices, Texas, (USA) with or without fibrinolysis |

| Other thrombectomy techniques | Flow Triever System (Inari Medical, USA) with 3 nitinol discs. Suction catheters up to 24 French |

| Indigo® (Penumbra, Alameda, USA). | |

CDT: catheter-directed thrombolysis; PTE: pulmonary thromboembolism.

The randomised ULTIMA trial and the prospective SEATTLE II trial demonstrated that ultrasound-assisted thrombolysis resulted in a more rapid decrease in the RV/LV ratio in patients with intermediate-risk acute PTE compared to anticoagulation therapy alone, with no evidence of significant bleeding and not demonstrating superiority of ultrasound-enhanced thrombolysis over standard catheter-directed thrombolysis.33,34

Mechanical catheter thrombectomyA variety of mechanical devices have been described in the literature, including large bore, pharmacomechanical and computer-assisted aspiration catheters (Fig. 3).

- none-

Manual aspiration can be performed by placing catheters or large bore introducer sheaths in the pulmonary arteries (Table 2). A major limitation is the small diameter of the catheter compared to the size and volume of clots in patients with central PTE. Specialised catheters have been developed, such as the Pronto thrombectomy catheter (Vascular Solutions Inc., Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA), for manual aspiration.

- none-

The Penumbra Indigo® device (Penumbra, Alameda, (USA) is a thrombectomy aspiration catheter connected to a high-pressure suction pump. It is available in sizes 8–16 Fr. During suction, rapid blood loss can occur and must be monitored in the collection chamber, as the current system does not allow for recycling of aspirated blood (Table 2). As the catheter can become clogged during the procedure, it is often used with a retractor guidewire (SEP®, Penumbra, Alameda, CA, USA) to try to keep it unblocked and perform mechanical thrombolysis, with significant improvement in RV overload according to various reports, including the EXTRACT-PE study.26,35–39

- none-

The Angio Vac (Angiodynamics, Latham, NY, USA) is a large-bore suction device which can evacuate large amounts of clots while recirculating filtered blood. Requires placement of a large bore introducer sheath (26 and 16 Fr) and general/perfusion anaesthesia, while the patient is placed on extracorporeal venovenous bypass. Another limitation is that the suction catheter is rigid and can be difficult to navigate safely in the lung region (Table 2). Major complications have been reported, including perforation of the free wall of the RV and distal clot embolisation.40

- none-

The FlowTriever device (Inari Medical Inc., CA, USA) has three components (nitinol discs, external suction catheter and proximal suction/retraction handle). The inner guide consists of three softly braided nitinol discs which are unsheathed in the thrombosed target vessel. The discs are designed to self-expand and break up the clot without damaging the vessel walls. Once the thrombus is captured, retraction is performed via the aspirator handle, which combines suction and mechanical retraction forces to clear the clot-containing nitinol discs through the guide catheter. The device comes in three selectable sizes, depending on the size of the target vessel. The current one for the treatment of PTE28 is inserted through a 22 Fr introducer sheath; therefore, it requires a considerable incision at the venotomy site and placement of this large diameter sheath into the pulmonary artery. For those who wish to avoid the larger diameter introducer sheath and do not need the suction component, the nitinol discs can be inserted through the 12 Fr introducer sheath. As with all mechanical or suction devices, they can be used with or without local thrombolytic injection (Table 2). A recent prospective multicentre trial demonstrated the efficacy and safety of the FlowTriever system with a major complication rate of 3.8% and the need for adjunctive thrombolytics in only 2% of patients.28

- none-

The Aspirex System (Straub Medical, Wangs, Switzerland) is available in Europe in sizes from 6 to 10 Fr. This device uses a rotating Archimedes screw (up to 40,000 rotations per minute) inside a flexible catheter, which can be inserted using angiographic guidance. During activation, negative pressure is created within the catheter lumen to aspirate and macerate the thrombus through an L-shaped aspiration port.33 The system uses the patient’s own blood to transport the thrombus through the catheter and cool the rotating screw. However, the suction mechanism sometimes creates a vacuum in the vessel, resulting in poor flow. If this occurs, infusion of additional fluids (i.e. saline) through the catheter may help facilitate device function. Pressure infusion requires an introducer sheath at least 1 Fr larger than the size of the selected Aspirex catheter, taking into account that the suggested aspiration volumes are 45 ml/min (6 Fr), 75 ml/min (8 Fr) and 180 ml/min (10 Fr). In addition, the pitch of the Archimedes screw, the number of rotations per minute and the size of the suction port can be adjusted to minimise vessel collapse and injury (Table 2). During aspiration, blood loss in the collection chamber must be closely monitored.41

High and intermediate/high risk PTE is a disease with high mortality rates and timely treatment is therefore essential to save lives. In the absence of contraindications, patients with massive PTE should be treated immediately with full-dose intravenous systemic thrombolysis. The subset of patients for whom systemic thrombolysis is not successful and who continue to show haemodynamic compromise or those with contraindications for fibrinolysis are candidates for catheter-directed endovascular treatment and even surgical embolectomy, although this surgical approach carries higher risks. The decision algorithm for intermediate/high risk (submassive) PTE is complex and a multidisciplinary team approach will help to decide the optimal timing of endovascular treatment.

FundingThis study did not receive any type of funding.