Incorporating coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA) in the hospital workup for suspected acute coronary syndrome requires appropriate skills for interpreting this imaging test. Radiologists’ skills can affect the interobserver agreement in evaluating these studies.

ObjectiveTo determine the interobserver agreement according to radiologists’ experience in the interpretation of coronary CTA studies done in patients who present at the emergency department with acute chest pain and low-to-intermediate probability of acute coronary syndrome.

Materials and methodsWe studied the interobserver agreement in the urgent evaluation of coronary CTA studies in which CAD-RADS was used to register the findings. We created pairs of observers among a total of 8 assessors (4 attending radiologists and 4 radiology residents). We used the kappa coefficient to estimate the overall concordance and the concordance between subgroups according to their experience.

ResultsThe agreement was substantial between experienced radiologists and residents (k=0.627; 95%CI: 0.436–0.826) as well as between all the pairs of observers (k=0.661; 95%CI: 0.506–0.823) for all the CAD-RADS together. The degree of agreement within the group of experienced radiologists was greater than that within the group of residents in all the analyses. The agreement was excellent for the overall CAD-RADS (k=0.950; 95% CI: 0.896–1) and for CAD-RADS ≥ 4 (k=1); the agreement was lower for CAD-RADS ≥ 3 (k=0.754; 95% CI: 0.246–1.255). The agreement for the residents for these categories was k=0.623, k=0.596, and k=0.473, respectively.

ConclusionThe agreement among attending radiologists regarding the assessment of urgent coronary CTA studies is excellent. The agreement is lower when residents are paired with attending radiologists. These findings should be taken into consideration when implementing coronary CTA in emergency departments and in the organisation of radiological staff for interpreting and reporting this imaging test.

La incorporación de la angiografía coronaria por tomografía computarizada (ACTC) a la atención sanitaria en las urgencias hospitalarias hace necesario una adecuada capacitación para la interpretación de esta prueba de imagen. Esta capacitación puede afectar al grado de concordancia interobservador de los radiólogos que evalúan dichos estudios.

ObjetivoEvaluar la concordancia interobservador en función de la experiencia en la interpretación de ACTC realizadas a pacientes que acuden a urgencias por dolor torácico agudo (DTA) con probabilidad baja-intermedia de síndrome coronario agudo (SCA).

Materiales y métodoEstudio de concordancia interobservador en la evaluación de ACTC realizadas en contexto urgente utilizando CAD-RADS como registro de resultados. Se crearon parejas de observadores entre un total de 8 evaluadores (4 staff y 4 en formación). Se estimó el grado de concordancia global y entre subgrupos de acuerdo con su experiencia mediante el coeficiente kappa.

ResultadosLa concordancia fue sustancial entre radiólogos experimentados y en formación (k=0,627; IC95%: 0,436−0,826), así como para todas las parejas de evaluadores (k=0,661; IC95%: 0,506−0,823) para todas las categorías CAD-RADS en conjunto. El grado de acuerdo del grupo de radiólogos experimentados fue superior al de los radiólogos en formación en todos los análisis realizados. La concordancia fue excelente para CAD-RADS global (k=0,950; IC95%: 0,896−1) y para CAD-RADS ≥ 4 (k=1), observando un menor acuerdo para CAD-RADS ≥ 3 (k=0,754; IC95%: 0,246−1,255). Los valores del personal en formación para estas categorías fueron k=0,623, k=0,596 y k=0,473, respectivamente.

ConclusiónLa concordancia entre radiólogos staff en la evaluación de ACTC realizadas a pacientes en el contexto de urgencias es excelente. El grado de acuerdo es menor cuando el personal inexperto forma parte de las parejas analizadas. Debemos tener en consideración estos datos en la implantación de esta prueba de imagen en la urgencia hospitalaria y en la organización del personal de radiología para su interpretación e informe.

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is currently one of the most important causes of mortality and morbidity on a worldwide level1 and is responsible for a third of deaths in subjects over the age of 35 years.2 Acute chest pain (ACP) is one of the most frequent reasons for consultation in the hospital emergency setting,3 accounting for up to 3.5% of all emergencies treated in our hospital; 11% of these are cases of acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA) is a radiology test capable of assessing the presence of coronary disease with high diagnostic accuracy, and it has the advantage over a coronary angiogram (the technique considered the gold standard) of being a less gruelling test with fewer risks, as well as being less expensive.4 Currently, the most accepted and standardised form for recording the results is CAD-RADS (Coronary Artery Disease Reporting and Data System),5 a system which seeks effective communication between the between the radiologist and the clinician, while also providing recommendations for action in each category.

The diagnostic accuracy of CTA has been extensively evaluated6–9 and multiple factors are known which could have a bearing on the final result of the radiology report (the technical parameters of the machine and of the study, image quality, post-processing tools, etc.). Moreover, the experience of the radiologists assessing the image test can also have a significant bearing on its diagnostic accuracy. Agreement on the interpretation of the CTA is between moderate and excellent for expert evaluators.10–13 However, the agreement between experienced radiologists and trainee radiologists (resident physicians) is unknown; nor do we know this degree of agreement in patients coming to the emergency department with acute chest pain and a low to intermediate probability of ACS. The aim of this study was to evaluate the inter-observer agreement between emergency department staff radiologists and trainee radiologists in the interpretation of CTAs performed in this setting.

Materials and methodsFor the drafting of this article, the Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS) have been taken as a reference.14

This concordance study forms part of larger study derived from a predictive model of significant stenosis in patients with ACP with suspected ischaemic origin attending hospital emergency departments. The patients in this study were recruited prospectively at the Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal [Ramón y Cajal University Hospital] (Madrid) and the Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe [La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital] (Valencia) between 20 July 2017 and 13 November 2019. The study was approved by the ethics committees at the sites where it was conducted, and all patients signed the corresponding informed consent form. The inclusion criteria were age over 30 years, presence of chest pain with suspicion of ischaemic origin, negative high-sensitivity troponin (hs-cTnI) (using each site's own cut-off point for normality on the basis of the availability of hs-cTnI) and non-diagnostic electrocardiogram of ACS. The exclusion criteria were the presence of haemodynamic instability or of severe arrhythmia, causes of ACP other than myocardial ischaemia (by means of an exhaustive physical examination, complementary laboratory and radiological tests in accordance with each site's protocols) and the presence of known coronary disease.

Adhering to the protocol established at each site, a CTA was performed on patients who presented with intermediate-low probability of ACS. These CTAs were reported by the habitual emergency department staff or by the staff on call. A sample of these tests was then selected for the proposed inter-observer agreement sub-study. A random selection was made so that the sample had at least one third of pathological studies (defined as CAD-RADS ≥3) and two thirds non-pathological studies.

A total of eight radiologists participated in the study (four emergency care staff radiologists and four trainees). Each of the CTAs introduced into the study was incorporated consecutively, in a previously designed pairing table. This table paired the same number of occasions to each observer as the rest of the evaluators at their site. Thus, a balanced design of image distribution between the group of radiologists was made with a total of 96 CTA studies read on two occasions, reaching a total of 192 readings. Each radiologist evaluated a total of 24 studies in a pair-blinded, independent manner, without access to any clinical information on the patient. Subsequently, the agreement between the pairs was evaluated as detailed in the statistical analysis section.

The emergency care staff radiologists had more than one year's experience in the reading of CTAs, with a minimum of 175–250 studies viewed. The trainee radiologists were 2νδ− to 4th-year residents in the specialty of radiodiagnosis, with training in their rotations in thoracic radiology and emergency care radiology, having viewed approximately 50–75 studies.

With regard to the technical protocol of the CTAs evaluated, the computed tomography (CT) models used were Canon Aquilion One (320 detectors, volumetric, slice thickness 0.5mm, rotation time 0.35s) and Philips (256 detectors, helical, slice thickness 0.8mm, rotation time 0.27s). To perform the CTAs, a 14−16cm volumetric study was obtained, including from the tracheal carina to cardiac apex. The ROI (region of interest) was positioned on the descending aorta, with a threshold of 200 HU. With respect to the dose of contrast, 70 cc of intravenous contrast (IVC) was used with 370 or 400mg/mL of iodine at a flow of 5ml/s, with subsequent bolus of 40 cc of saline through an 18, 20 or 22 gauge cannula. If necessary, beta-blocker premedication was used prior to and/or immediately before being performed (5mg ampoules of metoprolol i.v.). The vasodilator used was solinitrina (glyceryl trinitrate) in the form of a tablet or sublingual spray (objective dose of 0.4mg). After the acquisition of the study, images were sent to the PACS System in DICOM format. For the proper evaluation of the study, they were processed on VES® (Vitrea Enterprise Suite) software or in Synapse 3D®.

From each study evaluated, the observers reported: percentage of stenosis in the different coronary segments, type of plaque, evaluation capacity for each one of said segments, final CAD-RADS category, vessel of greatest stenosis, modifiers (stent, graft, vulnerable plaque, non-diagnostic test), dominance, coronary origin (normal vs. anomalous), coronary artery trajectory (normal vs. anomalous), and other non-coronary findings. For each one of the studies, the diagnostic quality was also reported using the following categories: optimal quality, free of artefacts. Good quality: with discrete artefacts that do not limit the assessment of stenosis. Acceptable quality: with moderate artefacts that slightly limit the assessment of stenosis. Poor/sub-optimal quality: with important artefacts, non-diagnostic study.

In the agreement evaluation, we decided to create two subcategories which are, in our opinion, of paramount importance in patient management. Firstly, it was decided to create a CAD-RADS ≥3 subcategory, given that, on the basis of this level, the CAD-RADS considers ACS possible or probable, with a recommendation of changes in the patient's treatment and the strong consideration of admission to hospital (with the possibility of further complementary tests). Secondly, we considered it useful to create the subcategory CAD-RADS ≥4, given that, as of this level, the CAD-RADS considers ACS probable or highly probable, with a clear recommendation for the points mentioned above, along with strong consideration of coronary angiography (invasive test), even on an emergent basis. Thus we evaluated two different points of patient management; on one hand, the agreement of the observers on the recommendation that the patient not leave the hospital, by means of CAD-RADS category ≥3; and on the other hand, we evaluated the agreement on the strong recommendation of considering an angiogram (invasive test) by means of CAD-RADS category ≥4.

Statistical analysisFor the analysis of agreement, the kappa coefficient was estimated with a 95% confidence interval. An agreement analysis was performed between both groups of observers (experienced and trainee radiologists). The degree of internal agreement within each group of radiologists was also studied. For the interpretation of the kappa coefficients calculated, we used the classification proposed by Landis & Koch.15 Values k <0.20 were considered poor agreement; values between 0.21 and 0.40 were considered slight agreement, values between 0.41 and 0.60 were considered moderate agreement, k values between 0.61 and 0.80 were considered substantial agreement, and k values between 0.81 and 1.00 were considered excellent agreement. For these analyses, the kappa2 command from the Stata statistical software version 16 was used.

ResultsA total of 96 patients were selected, from whom four studies had to be excluded as no valid reading was obtained by any of the observers. The images were catalogued as excellent-optimal quality in 36% of cases, and as sub-optimal or poor quality in 17% of cases. The remaining images presented good or acceptable image quality.

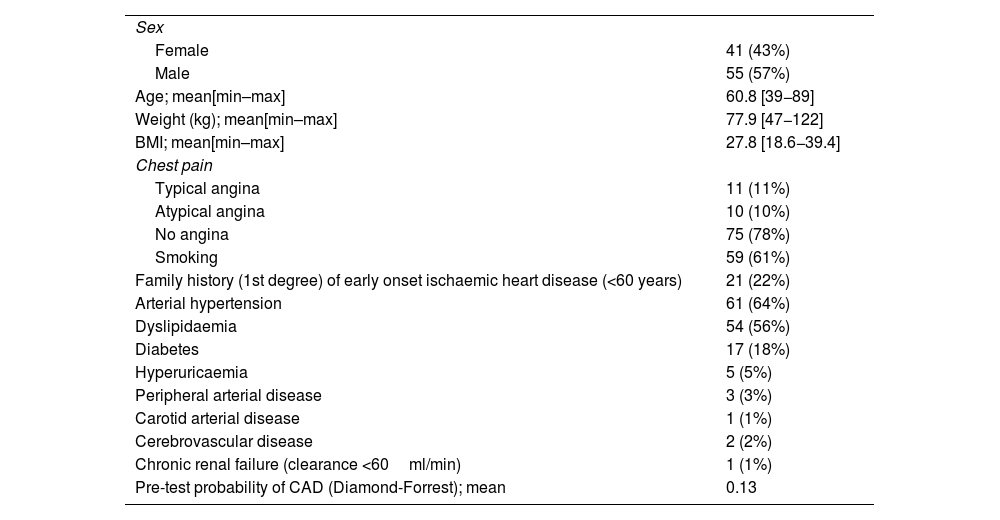

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of the study patients. There was a greater percentage of males (57%), with the mean age being 60.8 Years. 75% of patients presented with non-angina chest pain. The most frequent risk factors were smoking (61%), arterial hypertension (64%), and dyslipidaemia (56%). The pre-test probability of coronary artery disease according to the Diamond-Forrest model showed a mean of 13% with a maximum of 44%.

Clinical characteristics of the study patients.

| Sex | |

| Female | 41 (43%) |

| Male | 55 (57%) |

| Age; mean[min–max] | 60.8 [39−89] |

| Weight (kg); mean[min–max] | 77.9 [47−122] |

| BMI; mean[min–max] | 27.8 [18.6−39.4] |

| Chest pain | |

| Typical angina | 11 (11%) |

| Atypical angina | 10 (10%) |

| No angina | 75 (78%) |

| Smoking | 59 (61%) |

| Family history (1st degree) of early onset ischaemic heart disease (<60 years) | 21 (22%) |

| Arterial hypertension | 61 (64%) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 54 (56%) |

| Diabetes | 17 (18%) |

| Hyperuricaemia | 5 (5%) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 3 (3%) |

| Carotid arterial disease | 1 (1%) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2 (2%) |

| Chronic renal failure (clearance <60ml/min) | 1 (1%) |

| Pre-test probability of CAD (Diamond-Forrest); mean | 0.13 |

The heart rate of the patients prior to performing the study was 64.2 [50–85] beats per minute (bpm). The heart rate of the patients during the performance of the study (after medication) was 59.4 [50–72] bpm. 93% of the CTAs were performed on patients in sinus rhythm. The acquisition type was prospective in 76% of cases, the rest being retrospective. The most frequent type of study was helical (53%), these being somewhat more frequent in volumetric studies.

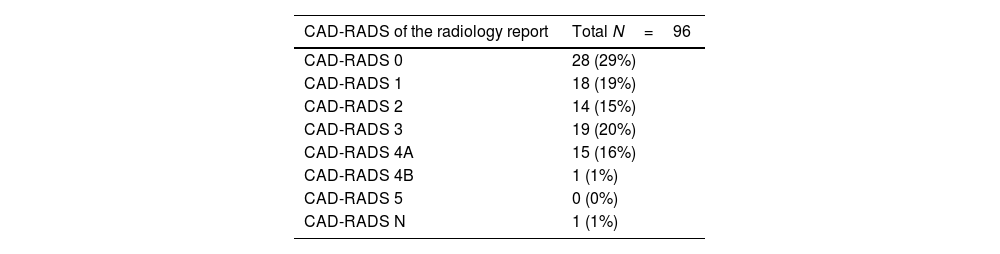

The radiological characteristics of patients in the sample based on the report on the CTA performed in the emergency department by the staff personnel or on-call personnel can be found in Table 2. The most frequent CAD-RADS categories were CAD-RADS 0 (29%) and CAD-RADS 3 (20%).

Radiological findings reported by habitual emergency care staff.

| CAD-RADS of the radiology report | Total N=96 |

|---|---|

| CAD-RADS 0 | 28 (29%) |

| CAD-RADS 1 | 18 (19%) |

| CAD-RADS 2 | 14 (15%) |

| CAD-RADS 3 | 19 (20%) |

| CAD-RADS 4A | 15 (16%) |

| CAD-RADS 4B | 1 (1%) |

| CAD-RADS 5 | 0 (0%) |

| CAD-RADS N | 1 (1%) |

| Percentage of stenosis | 0% | 1−24% | 25−49% | 50−69% | 70−99% | 100% | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary artery segment | |||||||

| RCp | 71 (74%) | 6 (6%) | 6 (6%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (9%) |

| RCm | 51 (53%) | 11 (11%) | 8 (8%) | 10 (10%) | 9 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (5%) |

| RCd | 76 (79%) | 6 (6%) | 2 (2%) | 4 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (6%) |

| AM | 76 (79%) | 3 (3%) | 3 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (15%) |

| LMCA | 84 (88%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (3%) |

| LADp | 66 (69%) | 9 (9%) | 5 (5%) | 10 (10%) | 4 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) |

| LADm | 71 (74%) | 9 (9%) | 4 (4%) | 4 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (6%) |

| LADd | 66 (69%) | 8 (8%) | 5 (5%) | 9 (9%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (6%) |

| 1st Diagonal Branch | 72 (75%) | 4 (4%) | 4 (4%) | 10 (10%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (5%) |

| Other LAD branches | 75 (78%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 6 (6%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (10%) |

| Cxp | 79 (82%) | 3 (3%) | 4 (4%) | 3 (3%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (5%) |

| Cxd | 75 (78%) | 4 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 4 (4%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (10%) |

RC: right coronary artery; AM: acute marginal artery; LMCA; left main coronary artery; LAD: left anterior descending artery; Cx: circumflex; p: proximal segment; m: medial segment; d: distal segment.

2.1 Number of patients per CAD-RADS category.

2.2 Number of patients per stenosis percentage in the different coronary segments.

The highest number of stenoses greater than or equal to 50% were found in the medial segment of the right coronary artery (n=19), followed by the proximal segment of the left anterior descending artery (n=14). Those segments in which no stenosis was found on the greatest number of occasions were the left main coronary artery (n=84) and the proximal segment of the circumflex artery (n=79). 92% of patients presented right dominance, and over 96% presented normal coronary origin and trajectory. In two cases, signs of pulmonary thromboembolism were detected as a non-coronary finding.

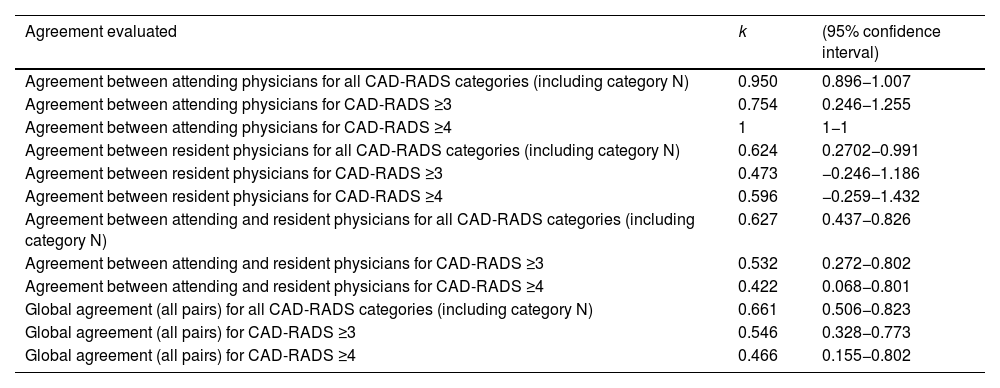

In the agreement sub-study, for some reason, four of the studies were only evaluated by one observer, owing to which they were excluded. Results of the inter-observer agreement for all CAD-RADS categories as a whole (including category N), as well as for CAD-RADS ≥3 and for CAD-RADS ≥4, are shown in Table 3.

inter-observer agreement according to level of experience.

| Agreement evaluated | k | (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|

| Agreement between attending physicians for all CAD-RADS categories (including category N) | 0.950 | 0.896−1.007 |

| Agreement between attending physicians for CAD-RADS ≥3 | 0.754 | 0.246−1.255 |

| Agreement between attending physicians for CAD-RADS ≥4 | 1 | 1−1 |

| Agreement between resident physicians for all CAD-RADS categories (including category N) | 0.624 | 0.2702−0.991 |

| Agreement between resident physicians for CAD-RADS ≥3 | 0.473 | −0.246−1.186 |

| Agreement between resident physicians for CAD-RADS ≥4 | 0.596 | −0.259−1.432 |

| Agreement between attending and resident physicians for all CAD-RADS categories (including category N) | 0.627 | 0.437−0.826 |

| Agreement between attending and resident physicians for CAD-RADS ≥3 | 0.532 | 0.272−0.802 |

| Agreement between attending and resident physicians for CAD-RADS ≥4 | 0.422 | 0.068−0.801 |

| Global agreement (all pairs) for all CAD-RADS categories (including category N) | 0.661 | 0.506−0.823 |

| Global agreement (all pairs) for CAD-RADS ≥3 | 0.546 | 0.328−0.773 |

| Global agreement (all pairs) for CAD-RADS ≥4 | 0.466 | 0.155−0.802 |

For the interpretation of the kappa coefficients calculated, we used the classification proposed by Landis & Koch.15k values <0.20: poor agreement; k=0.21−0.40: slight agreement; k=0.41−0.60: moderate agreement; k=0.61−0.80: substantial agreement; k > 0.81: excellent agreement.

Agreement between experienced and trainee radiologists was substantial for all CADS-RADS categories as a whole (k=0.627; 95%CI: 0.436−0.826). Global agreement taking into account all the pairs was also substantial for all CADS-RADS categories as a whole (k=0.661; 95%CI: 0.506−0.823). The degree of agreement in the experienced radiologists group was higher than in that of the trainee radiologists in all analyses performed. This was excellent for global CAD-RADS (k=0.950; 95%CI: 0.896–1) and for CAD-RADS ≥4 (k = 1) with lower agreement for CAD-RADS ≥3 (k = 0.754). The values for these categories of the trainee personnel were k=0.623, k=0.596 and k=0.473, respectively.

DiscussionThe results show an excellent degree of agreement among emergency care staff radiologists in this image test. This finding is in line with the data from the scientific literature for agreement among expert observers.10–13 Moreover, this study demonstrates that agreement among these staff radiologists is excellent in the evaluation of the CTA of patients with ACP and intermediate-low probability of ACS (emergency setting). A drop in the degree of agreement was observed in the rest of the agreement analyses (trainee-trainee and staff-trainee pairs, and all pairs in general) with respect to the agreement of staff radiologists. As has been explained in previous articles, agreement among resident physicians after one year of training in coronary CT continues to be moderate (k=0.48; 95%CI: 0.42−0.54)14, thus the lower levels of agreement obtained when inexperienced staff participate in the analysed pairs was to be expected.

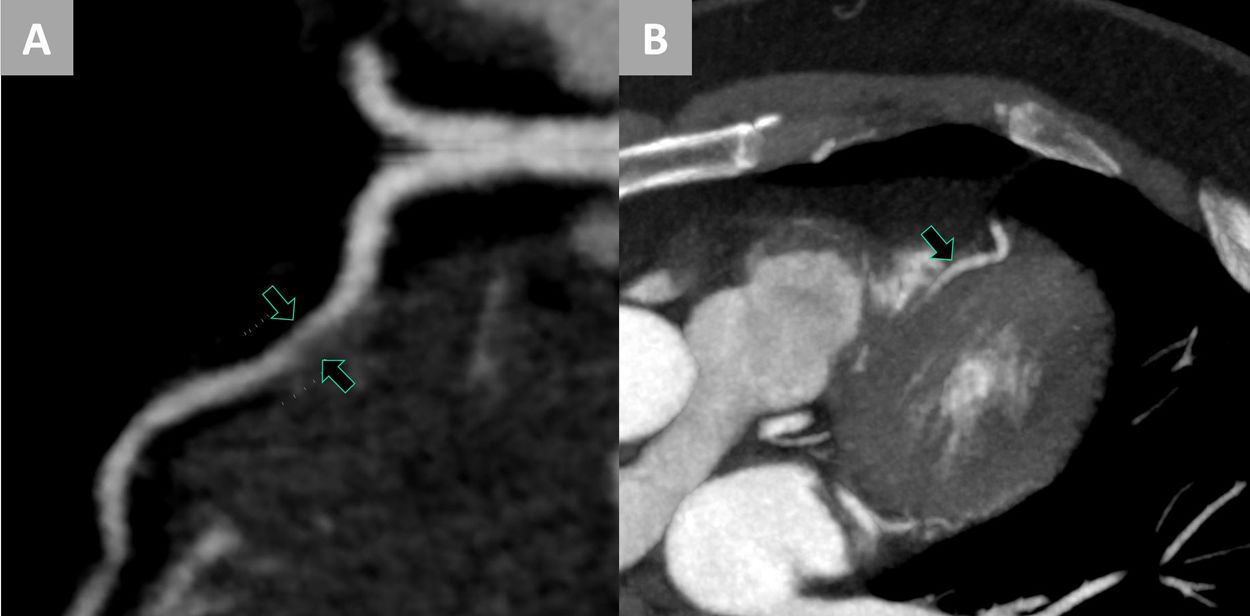

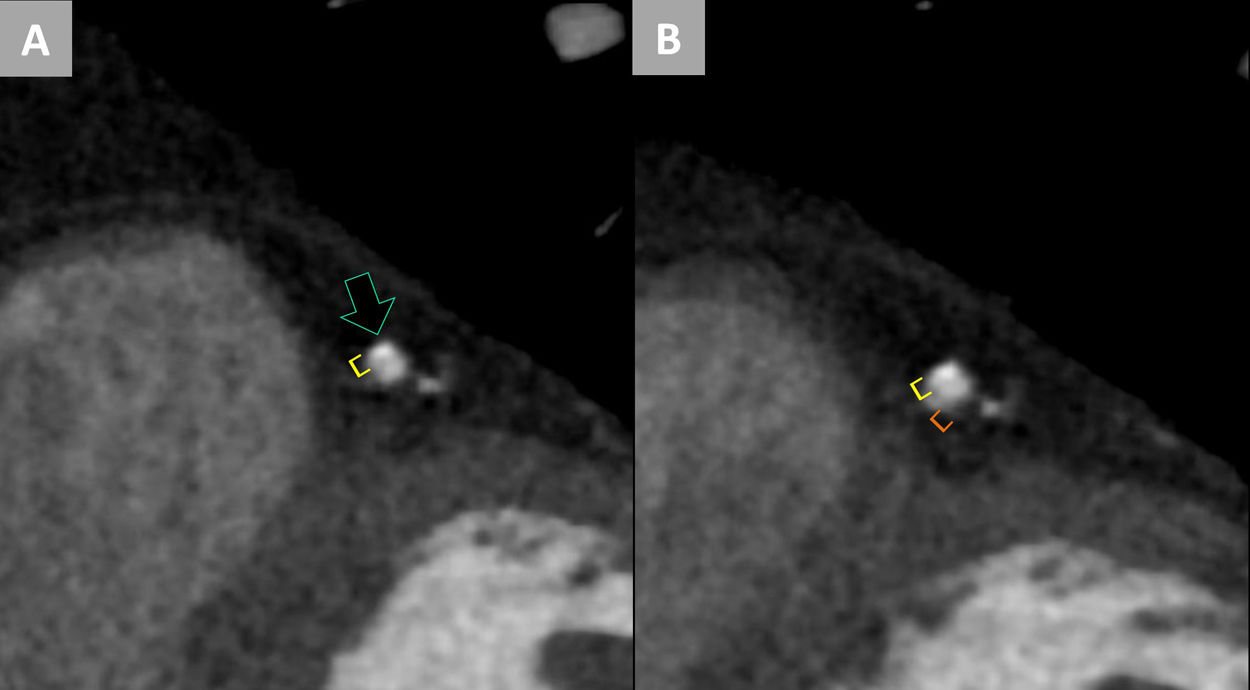

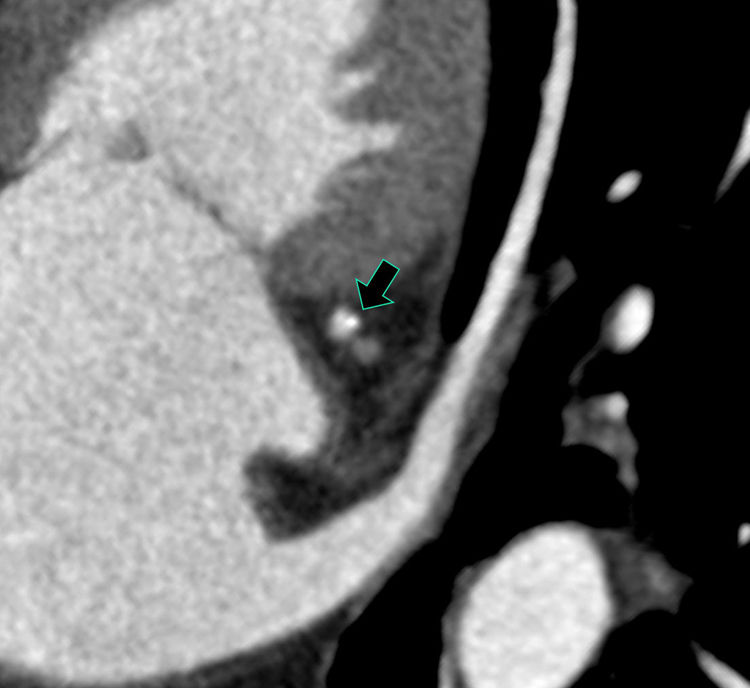

Among staff radiologists, three discrepant studies were observed, all of them owing to a difference in CAD-RADS between adjacent categories. Among non-expert staff, a total of nine discrepant studies were found, there being several studies with a wide variation across the CAD-RADS spectrum (more than 1 category). This may be related with the scant experience of these observers in assigning the percentage of stenosis. The number of discrepancies between experienced staff and trainees totalled 32 (56% of these pairings). In those studies where the result differed by more than one category within the CAD-RADS spectrum, the results would seem to suggest that an important part of the discrepancies of this type are due to the non-visualisation of an existing plaque or to the interpretation thereof as an artefact more than as a genuine difficulty in assigning the percentage of stenosis to a visualised plaque. This had already been proposed in previous studies.12Figs. 1–3 show a number of examples of the discrepancies found.

Discrepancy between emergency care staff personnel and non-expert personnel. A) Computed tomography image using curved multiplanar reconstruction. We can see an apparently non-calcified plaque (arrows), located in the medial segment of the left anterior descending artery, with important stenosis in its lumen. This finding was evaluated by the non-expert observer as stenosis 60% and resulted in a final report of CAD-RADS 3. B) Image of multiplanar reconstruction using a different phase in the cardiac cycle. At the previously described location, this non-calcified plaque is not identified (arrow), it probably being an artefact due to heartbeat motion and partial volume in image A. The emergency care staff observer who evaluated this study reported a CAD-RADS 0.

Discrepancy between non-expert personnel. A) Computed tomography image performing a multiplanar reconstruction transversal to the axis of the vessel. We can see a partially calcified plaque in the anterior aspect of the medial left anterior descending artery (arrow). This plaque was interpreted by an initial non-expert observer as stenosis <25% (yellow brackets) with the final result of the study being CAD-RADS 1. B) In another multiplanar reconstruction cross-section similar to the previous one, we can observe that the previously described plaque appears to be accompanied by another non-calcified component in the posterior aspect of the vessel (orange brackets). This component seems not to have been identified by the first observer. The second non-expert evaluator did consider this component and concluded the study as stenosis 50-60% (CAD-RADS 3). These wide variations in the degree of stenosis appear in a number of the discrepancies between non-expert personnel, most probably owing to their scant practice in the identification of plaques and in assigning the percentages of stenosis.

Discrepancy between emergency care staff personnel. Computed tomography image performing a multiplanar reconstruction transversal to the axis of the vessel. We can identify a plaque with focus of calcification in the right circumflex (arrow). While one of the emergency care staff radiologists evaluated this plaque as stenosis 20% (CAD-RADS 1), their partner evaluated this finding as stenosis 30% (CAD-RADS 2). Most of the cases of discrepancy obtained among experienced personnel were of this type. Small variations in the percentage of stenosis assigned changed the CAD-RADS category to the immediately adjacent one.

The right coronary artery and the left anterior descending artery were responsible for the greatest number of discrepancies; nonetheless, this finding seems to correspond to there having been a greater number of stenoses in these vessels rather than actual greater difficulty in evaluating these arteries. Further studies would be necessary to investigate whether there are coronary artery segments in which agreement is lower.

One of the most important limitations was that the number of readings when evaluating some of the specific instances of agreement were insufficient; hence, the confidence intervals obtained do not allow adequate conclusions to be drawn. The CAD-RADS ≥3 agreement category in the staff radiologists group is one with this limitation, it also being a highly important category from the point of view of clinical management (possibility of admission, changes in treatment, and subsequent coronary angiogram).5 Accordingly, further studies would be necessary to investigate this important subcategory of agreement.

Another of the limitations was that the observers evaluated the studies in the emergency setting several days after the test had been performed. Thus, the findings reported could have been influenced by the feeling of security of not actually intervening in the management of the patient.

The inclusion of experienced staff and trainees from different sites and with heterogeneous experience and backgrounds could lead to the same study performed on other observers giving rise to different results. A more regulated study in which experienced observers, on one hand, and beginners, on the other, had more homogeneous experience and training between them may have been more suitable. Nonetheless, we consider that the selection of the observers in this study represents the reality of clinical practice more faithfully, this also being a strength thereof.

The existing literature on CTA in patients in the emergency setting does not focus on evaluating whether the agreement between radiologists is the same in these patients as in those performed on a scheduled basis (which may differ in their characteristics). One of the strengths of this study is the analysis and demonstration that the agreement between emergency care staff radiologists evaluating studies performed on patients in this setting is excellent. A comparison of the degree of agreement between observers with different levels of experience is another of its strengths.

Lastly, we should point out that this study does not address the issue of how much training time is needed to acquire a suitable level of experience for evaluating the CTA, or what effect a possible prior training programme could have on improving the interpretation of the image test.

CTAs performed in the emergency setting are interpreted by heterogeneous personnel (emergency care staff radiologists, on-call radiologists, and trainee personnel). The results of this study show that the experience of emergency care staff radiologists is suitable for the CTA report, while this is not the case for the non-expert personnel. The practical application of these results is that an effective training programme is necessary so that all those radiologists who may need to report on this image test can do so with suitable guarantees. Guidelines such as those of the SCCT (Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography), specifying the necessary requirements for acquiring different degrees of training, may be a suitable starting point for training programmes.16 Lastly, we also consider it necessary to assess the need to establish an accreditation system for CTA reporting.

ConclusionsCTAs performed in the hospital emergency setting are habitually interpreted by heterogeneous personnel with different levels of training and experience. Taking this into account, we considered it necessary to provide information on the interpretability of this imaging test for evaluators with a moderate level of experience. This study has evaluated the agreement shown by emergency care staff radiologists in the interpretation of these CTAs, obtaining excellent results, similar to those described in prior studies for expert radiologists. The results show a drop in agreement when trainee personnel participate in the pairs of observers. Both the adequate agreement of emergency care staff personnel and the poorer results of non-expert personnel are data that we must take into consideration in the implementation of this imaging test in hospital emergency departments, and in the organisation of the radiology personnel for the interpretation and reporting thereof.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for the integrity of the study: AVB, PEL, JZ, LGC.

- 2

Study conception: AVB, IPH, PEL.

- 3

Study design: AVB, IPH, PEL, JZ.

- 4

Data collection: AVB, PEL, IPH, BP, JMBM, JCM, RPO, AO.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: LGC, AVB, AGG, JZ.

- 6

Statistical processing: AGG, JZ.

- 7

Literature search: LGC.

- 8

Drafting of the manuscript: LGC.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: LGC, AVB, AGG, JZ.

- 10

Approval of the final version: LGC, AVB, AGG, JZ.

This study was financed by the Carlos III Health Institute and ERDF "A way of making Europe" funding, through the multicentre project with references PI16/01653 and PI16/01597.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

B. Alba-Péreza, J.M. Blanc-Molinaa, J. Castellá-Malondab, R. Piquera-Olmedab and A. Oprisanb

aRadiodiagnostic Department, Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal [Ramón y Cajal University Hospital], Madrid, Spain

bHospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe [La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital], Valencia, Spain