To evaluate the most common reasons for requesting brain CT studies from the emergency department and to calculate the prevalence of urgent acute pathology on this population group.

Material and methodsWe reviewed brain CT studies requested from the emergency department during October and November 2018. We recorded the following variables: age, sex, reason for requesting the study, CT findings, use of contrast agents and reasons for using them, and, in patients who had undergone previous head CT studies, whether the findings had changed. SPSS was used for statistical analyses.

ResultsA total of 507 urgent brain CT studies were done (41.4% in men, 58.6% in women; mean age, 65.4±20 years).

The most common reason for requesting the study was head trauma (40.5%); only 15.6% of these studies showed acute posttraumatic intracranial lesions.

The second most common reason was focal neurologic symptoms (16%); only 16% of these studies showed recent ischemic infarcts or acute bleeding.

No pathological findings were reported in 43.2% of the studies.

The most common abnormal finding was ischemic lesions in small vessels (20%).

Space-occupying lesions (both benign and malignant) were found in 3.9% of all patients.

ConclusionsMost brain CT studies requested from the emergency department showed no findings that would modify the management of the patient. Overuse of urgent brain CT increases the radiology department’s workload and exposes patients to radiation unnecessarily.

Evaluar los motivos más frecuentes por los que se solicitan estudios de imagen craneales desde el Servicio de Urgencias y calcular la prevalencia de la patología aguda urgente en este grupo de población.

Material y métodosSe recogieron las tomografías computarizadas (TC) cerebrales solicitadas por el Servicio de Urgencias en los meses de octubre y noviembre de 2018. Se recogieron los siguientes datos: edad, sexo, motivo de solicitud del estudio, hallazgos encontrados en la prueba de imagen, administración de medios de contraste y motivo, y en caso de que el paciente tuviera estudios de imagen craneales previos, reseñar la existencia de cambios. Se utilizó el programa SPSS para hacer el análisis estadístico.

ResultadosSe realizaron 507 TC de cerebro urgentes, 41,4% en hombres y 58,6% en mujeres, con una edad media de 65,4±20 años. El motivo de solicitud más frecuente fue el traumatismo craneal (40,5%), y de ellos únicamente el 15,6% presentó patología intracraneal postraumática aguda. El segundo motivo fue por sintomatología neurológica focal (16%), de los cuales el 16% presentó infarto isquémico reciente o hemorragia aguda. En cuanto a los hallazgos, el 43,2% de los estudios fueron informados como normales. El hallazgo más frecuente fue lesiones isquémicas de pequeño vaso, en un 20%. En un 3,9% de todos los pacientes se encontraron lesiones ocupantes de espacio, incluidas lesiones tanto benignas como malignas.

ConclusionesLa mayoría de los estudios cerebrales solicitados desde urgencias no muestran patología que modifique el manejo del paciente. La sobreutilización de la TC cerebral urgente sobrecarga los servicios de radiología y someten a la población a radiación innecesaria.

Computed tomography (CT) has become an indispensable tool in regular medical practice, especially in emergency situations,1 in which a correct diagnosis must be made quickly.

Neurological emergencies are among the most common reasons for seeking care in emergency departments. In these cases, brain CT scans are useful for evaluating acute intracranial disease and determining its severity, with the aim of screening patients who require immediate surgical treatment and distinguishing them from those for whom medical management and observation are sufficient.2–5

This, coupled with the widespread availability of this technique in hospitals in our setting, has led to an exponential increase in requests for brain CT scans from emergency departments in recent decades.6 This, in turn, is giving rise to growing concern among the different radiology associations.1,7

It is important for urgent imaging tests to be clearly justified and indicated,8 since, otherwise, these patients are being subjected to not negligible doses of radiation, it being known that excessive use of such tests can have adverse effects on their health. These adverse effects are not to be overlooked,6,7,9 especially in the paediatric population.10

Furthermore, this problem affects not only the health of the population but also the health of the healthcare system, since unjustified imaging tests represent a substantial and unnecessary economic burden on the system.6,9

The main objective of this study was to calculate the prevalence of acute disease in brain CT scans requested from the emergency department in our setting. The most common reasons why brain imaging scans were requested from the emergency department at our hospital were evaluated.

Material and methodsThis was a single-centre, retrospective, observational, descriptive study in which all data were processed in an anonymised fashion. The study was approved by the Galicia Independent Ethics Committee, which determined that it was not necessary to obtain informed consent.

All brain CT scans requested from the emergency department for patients over 16 years of age between 1 October and 30 November 2018, inclusive, were compiled. Minors under 16 years of age were not included, as our hospital is not a referral hospital for this population type.

Each CT scan was interpreted urgently by the on-duty, consultant and/or resident radiologist, and then read by a neuroradiologist (with seven or 12 years of experience) the next day.

For each scan, patient demographic data (age and sex) and the reason for requesting the imaging test were collected. Where patients presented multiple symptoms simultaneously, the predominant or most significant symptom was taken into account. The findings reported in the diagnostic conclusion for the CT scan were also collected.

Brain CT scans were performed without administration of intravenous contrast (IVC). If on any occasion IVC had to be administered, the reason for deciding to administer it was recorded.

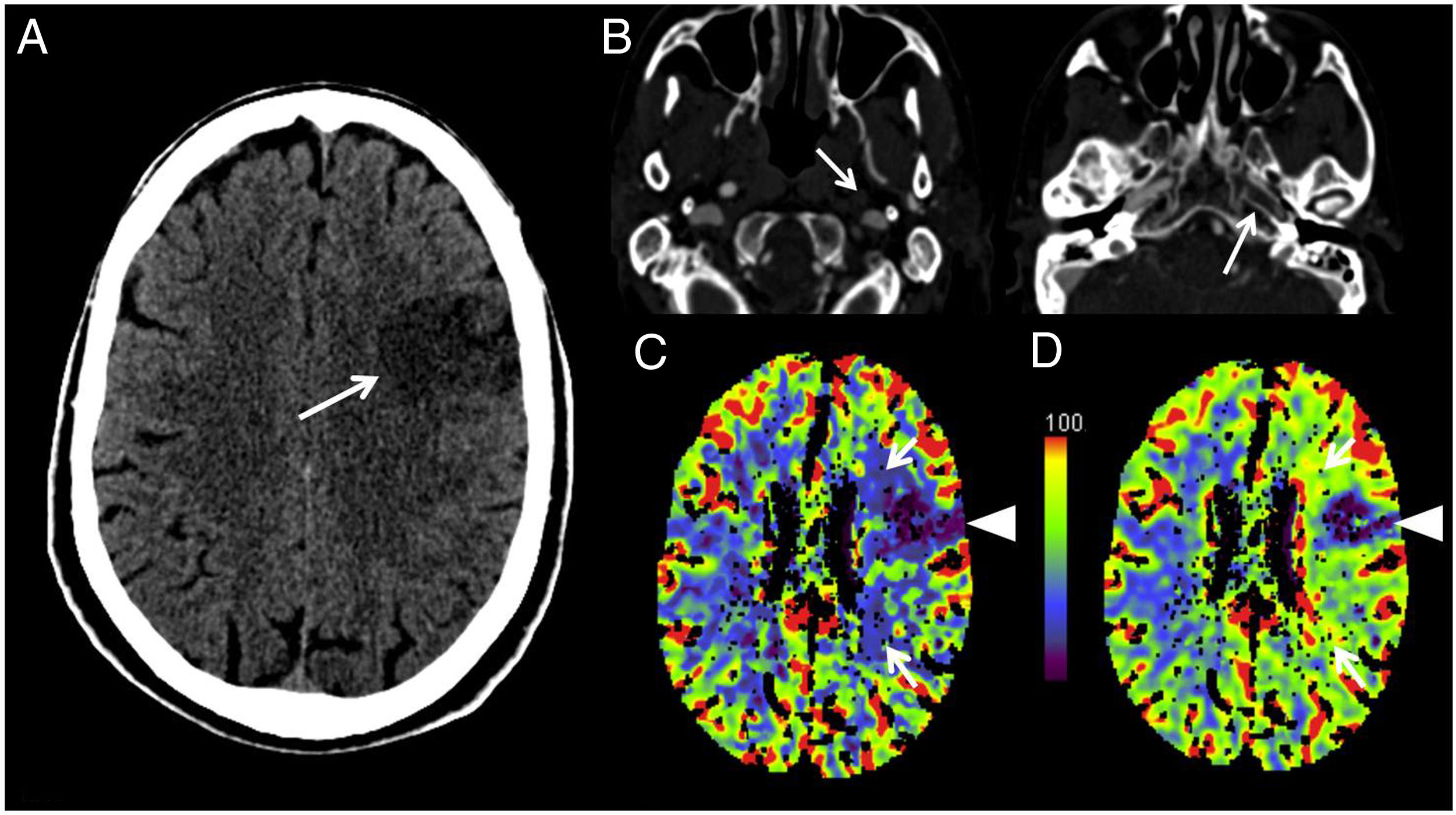

Our hospital has a “Stroke Code” protocol, in which an initial baseline CT scan is performed to rule out the presence of intracranial haemorrhage. Once this has been ruled out, the study is completed with CT angiography of the supra-aortic trunks (70ml of loperamide 300 at 4ml/s) and a perfusion study (60ml of loperamide 300 at 5ml/s), as shown in Fig. 1. Our hospital lacks interventional neuroradiology equipment, so if an acute ischaemic infarction eligible for endovascular treatment is confirmed, the patient is quickly transferred to another hospital in the same city that does have an interventional neuroradiology unit.

“Stroke Code” protocol. A) Computed tomography (CT) scan of the base of the skull, axial plane: left frontal hypodensity with loss of white/grey matter differentiation in relation to acute infarction (arrow). B) CT angiography of the supra-aortic trunks, axial plane: complete occlusion of the left internal carotid artery (arrows) in both its extracranial portion (left image) and its intracranial portion (right image). C) Perfusion CT, blood flow map, axial plane. D) Perfusion CT, blood volume map, axial plane: area with decreased blood flow and volume indicating an established infarction (arrow tips) and area of decreased flow with increased volume representing an area of penumbra with potential for revascularisation (white arrows).

It was also confirmed whether these patients had prior brain CT scans and, if so, whether significant changes had occurred between the emergency scan and the prior scan. Finally, information was collected on patient management — whether the patient had been admitted, transferred to another hospital or discharged home.

Once the data were collected, the scans were classified according to two criteria. First, considering that one of the study objectives was to calculate the prevalence of emergency acute disease in CT scans requested by the emergency department, the scans were grouped by the presence or absence of emergency acute disease. In this study, emergency disease was defined as disease that required immediate medical care,11,12 including: acute ischaemic disease (although the limitations of CT for ruling out emergency disease with a normal scan and for determining whether or not a small-vessel ischaemic lesion is acute must be considered); intracranial trauma (including fractures); non-traumatic haemorrhagic disease; space-occupying lesions (SOLs); and other types of disease associated with signs of herniation, acute hydrocephaly or intracranial infection.

It should be noted that, in many cases, the emergency scans revealed another type of disease that was not considered emergency disease according to the above definition, but was significant, since the diagnosis thereof changed the patient’s prognosis and management — for example, a brain tumour (primary or metastatic) or a demyelinating disease.

The second criterion for classifying scans was based on the reason for the request, with a view to determining the most prevalent findings in each group separately.

Statistical processing and analysis of the data were performed with the SPSS® (Chicago, Illinois) version 15 software program. This was used to calculate means, standard deviations and percentages.

ResultsA total of 507 CT brain scans requested by the emergency department in the selected two-month period were performed. Of these, 210 (41.4%) were in male patients and 297 (58.6%) were in female patients. The mean age was 65.4±20 years (range: 17–98 years).

The main reasons for requesting CT scans were traumatic brain injury followed by acute focal neurological deficit (Table 1). In some cases, patients presented multiple symptoms at the same time, but for classification purposes the predominant reason or symptom was taken into account.

Reasons for requesting emergency brain CT scans, grouped.

| Reason for request | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Trauma | 206 | 40.6 |

| Acute focal neurological deficit | 81 | 16 |

| Headache | 80 | 15.8 |

| Instability/dizziness | 53 | 10.5 |

| Altered level of consciousness | 49 | 9.7 |

| Seizures | 14 | 2.8 |

| Visual disturbance | 10 | 2 |

| Psychiatric symptoms | 7 | 1.4 |

| Cranial nerve palsy | 5 | 1 |

| Amnesia | 2 | 0.4 |

Out of all the patients included, 245 (48.3%) had previously undergone at least one brain CT scan at our hospital. Within this group, significant changes were seen in only 37 patients (7.3%); no changes were seen compared to the most recent scan in the remaining 208 cases (41%).

IVC was administered in 41 (8%) of the 507 emergency scans. In 23 cases (56.1%), this was due to a history of neoplasia that required ruling out metastatic disease; in 11 (26.8%), it was due to detection by the radiologist of a suspicious finding on the baseline CT scan without contrast; in four (9.8%), it was due to signs and symptoms or findings on CT that raised suspicion of the possibility of intracranial aneurysms; and in three (7.3%), it was for CT angiography of the supra-aortic trunks and a perfusion study within the “Stroke Code” protocol (Fig. 1).

Regarding patient management, 325 (64.1%) were discharged home from the emergency department, 175 (34.5%) were admitted to our hospital, and seven (1.4%) were transferred to another hospital to be treated with neurointerventional procedures not available at our hospital (one patient for treatment of cerebral aneurysms and the rest for endovascular treatment of stroke).

Findings of emergency brain CT scansWith respect to overall CT scan results, 219 (43.2%) of the scans were completely normal.

If the rest of the scans were divided into groups based on type of disease, the most common was ischaemic disease with 146 cases (28.8%); of these, 20 (3.9%) were acute or subacute infarctions. Acute trauma was the next most common, having been detected in 97 patients (19.1%), although of these just 32 (6.3%) had significant findings (when soft-tissue haematoma was excluded). All other disease groups, in order of frequency, were as follows: SOL, with 20 cases (3.9%); other disease, with nine cases (1.8%); infectious disease, with five cases (1%); postoperative changes, with five (1%) cases; non-traumatic haemorrhagic disease, with four cases (0.8%); and inflammatory disease, with two cases (0.4%).

According to the above-mentioned definition of emergency acute disease, of the total of 507 scans requested, emergency acute disease was found in just 61 studies (12%): trauma in 34 cases (6.7%), acute or subacute infarctions in 20 cases (3.9%), non-traumatic haemorrhages in four cases (0.8%), acute hydrocephaly in two cases (0.4%) and an SOL leading to herniation in one case (0.2%). Eight (1.6%) of the 507 cases showed significant disease (non-emergency disease that changed the patient's prognosis or management), consisting of three cases of metastases of new onset (0.6%), one case of progression of metastatic disease (0.2%), two cases of primary central nervous system tumours (0.4%), one case of an indeterminate SOL (0.2%) and one diagnosed case of demyelinating disease (0.2%). The remaining 219 scans (43.2%) corresponded to some other type of disease that did not meet the criteria for being included in either of the above two groups.

Analysis of the results by group based on the reason for requesting the test yielded the following findings:

TraumaTraumatic brain injury was the most common reason for requesting the test, with 206 patients (40.6%), of whom 94 (45.6%) were male and 112 (54.4%) were female, with a mean age of 66.6±21.6 years.

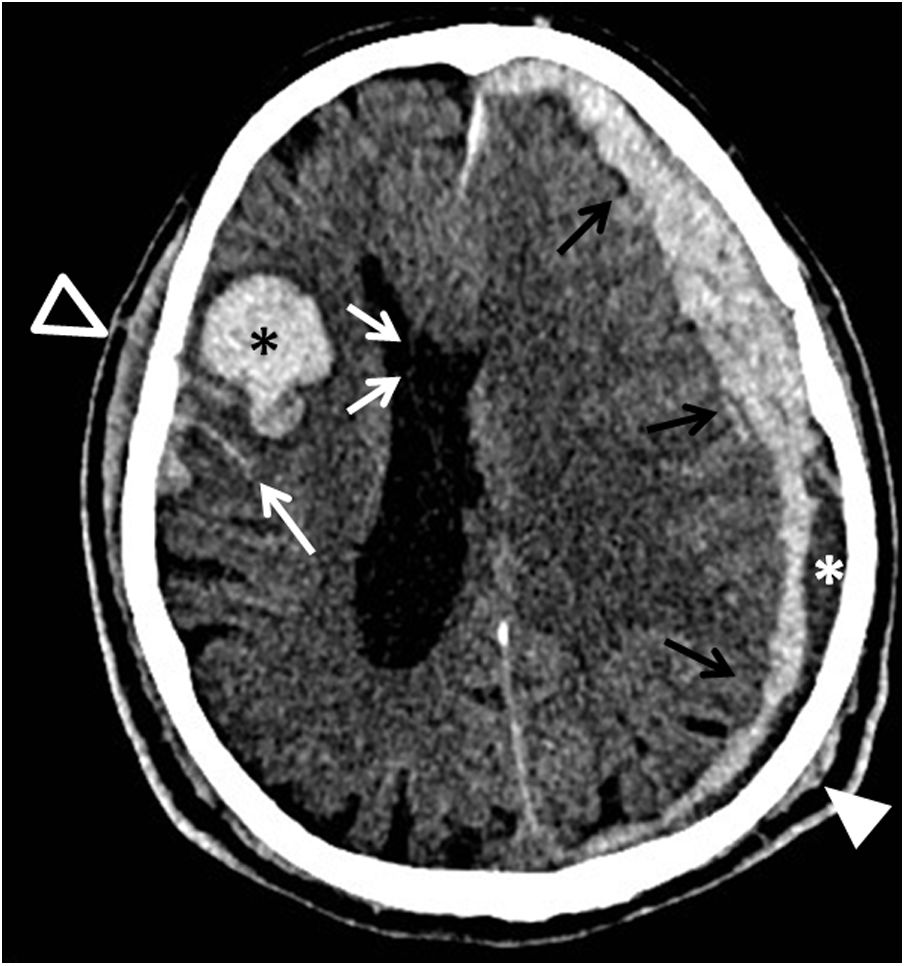

The results of the CT scans due to trauma are summarised in Table 2. Fig. 2 shows one of the cases with a combination of acute trauma included in Table 2.

Results of emergency brain CT scans requested due to traumatic brain injury.

| Trauma | Overall | No loss of consciousness | Loss of consciousness | For days/weeks | Associated with neurological symptom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 77 (37.4%) | 39 | 21 | 17 | 0 |

| Trauma | 92 (44.6%) | 62 | 21 | 8 | 1 |

| • Soft-tissue haematoma | 60 (29%) | 38 | 14 | 7 | 1 |

| • Fractures | 11 (5.3%) | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| • Subdural haematoma | 6 (2.9%) | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| • Parenchymal contusion | 4 (2%) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| • Subdural hygroma | 2 (1%) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| • SAH | 1 (0.5%) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| • Combination | 8 (3.9%) | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Ischaemic disease | 33 (16%) | 19 | 5 | 7 | 2 |

| • Acute infarctions | 1 (0.5%) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| • Chronic infarctions | 7 (3.4%) | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| • Small-vessel lesions | 25 (12.1%) | 13 | 4 | 6 | 2 |

| SOL | 3 (1.5%) | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Other | 1 (0.5%) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

SAH: subarachnoid haemorrhage; SOL: space-occupying lesion.

CT scan of the base of the skull, axial plane. A patient with traumatic brain injury who presented left parietal (white arrow tip) and right frontal (black arrow tip) soft-tissue haematomas, an acute subdural haematoma in the left convexity (black triple arrow), with areas of lower density inside, in relation to hyperacute bleeding (white asterisk), leading to midline deviation towards the right (white double arrow), right frontotemporal haemorrhagic contusion (black asterisk) and subarachnoid haemorrhage (white arrow).

SOLs consisted of one case of meningioma and one case of lymphoma, both already known, and one case of cholesteatoma. In the “other” group, all that was found was a case of stenosis of the cerebral aqueduct (also previously known).

Acute focal neurological deficitEighty-one patients (16%) had a brain CT scan requested due to an acute focal neurological deficit: 29 (35.8%) were male and 52 (64.2%) were female, with a mean age of 69.9±16.7 years.

The results of the CT scans due to acute focal neurological deficit are shown in Table 3. The number of normal studies, especially in the group of patients in whom signs and symptoms persisted (21; 25.9%), is striking. It is interesting to note that, in this particular group of patients, four (19%) were admitted to complete the study with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and an acute infarction not visualised on CT was identified in just one case (4.8%). Moreover, seven patients (33.3%) were admitted without undergoing a complementary imaging test. All other cases (10; 47.7%) were discharged.

Results of emergency brain CT scans requested due to acute neurological deficit.

| Focal neurological deficit | Overall | Persistent signs and symptoms | Resolved signs and symptoms (TIA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 25 (30.8%) | 21 | 4 |

| Ischaemic disease | 47 (58%) | 40 | 7 |

| • Acute infarctions | 12 (14.8%) | 12 | 0 |

| • Chronic infarctions | 11 (13.6%) | 7 | 4 |

| • Small-vessel lesions | 24 (29.6%) | 21 | 3 |

| Non-traumatic haemorrhage | |||

| • Parenchymal haematoma | 1 (1.3%) | 1 | 0 |

| SOL | 6 (7.4%) | 6 | 0 |

| Postoperative changes | 2 (2.5%) | 2 | 0 |

SOL: space-occupying lesion; TIA: transient ischaemic attack.

Fig. 1 shows an example of a case of acute infarction in which the “Stroke Code” protocol was followed.

In this group, SOLs corresponded to metastases in three (3.7%) of the cases (one of them [1.2%] was already known, though it was progressing, and the other two [2.5%] were newly diagnosed), known glioblastoma multiforme in one case (1.2%) and meningiomas in two cases (2.5%).

HeadacheHeadache was the third most common reason for requesting a CT scan, in 80 (15.8%) of the total number of patients; of these, 27 (33.8%) were male and 53 (66.2%) were female, with a mean age of 54.3±18.1 years.

The results of the CT scans due to headache are set out in Table 4. It can be seen that in the majority of cases, headache was a sole symptom, and in just 10 (12.5%) of the cases, headache was accompanied by other symptoms (six cases [7.5%] were accompanied by visual disturbances, one [1.25%] by visual disturbances and vomiting, one [1.25%] by vomiting and fever, and one [1.25%] by visual hallucinations).

Results of emergency brain CT scans requested due to headache.

| Headache | Overall | Sole symptom | Associated with other symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 51 (63.8%) | 45 | 6 |

| Ischaemic disease | 14 (17.4%) | 11 | 3 |

| • Chronic infarctions | 5 (6.2%) | 5 | 0 |

| • Small-vessel lesions | 9 (11.2%) | 6 | 3 |

| SOL | 4 (5%) | 4 | 0 |

| Infectious disease | 4 (5%) | 4 | 0 |

| Postoperative changes | 2 (2.5%) | 2 | 0 |

| Non-traumatic haemorrhage (SAH) | 1 (1.3%) | 1 | 0 |

| Other | 4 (5%) | 3 | 1 |

SAH: subarachnoid haemorrhage; SOL: space-occupying lesion.

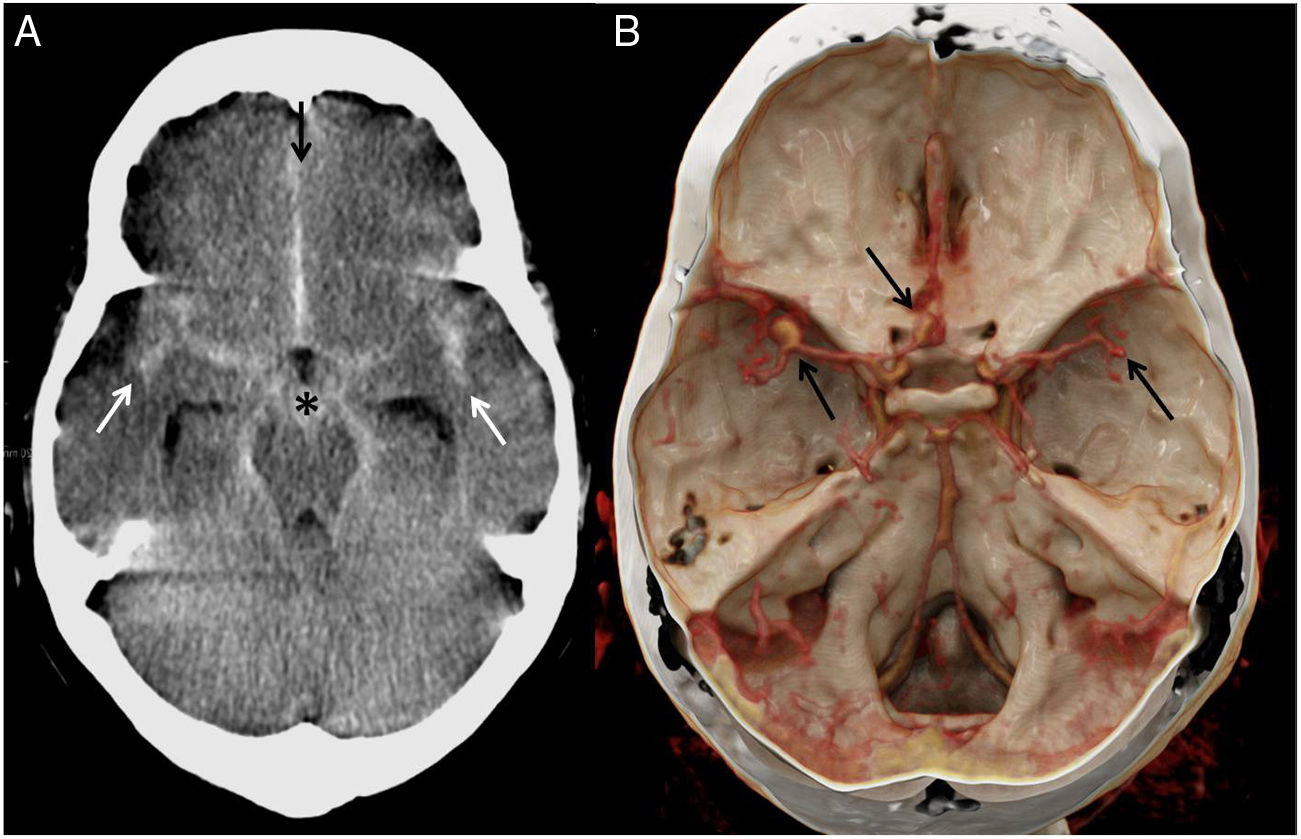

Fig. 3 shows the only case in the sample with a subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) secondary to rupture of intracranial aneurysms.

A) CT scan of the base of the skull, axial plane. Diffuse spontaneous hyperdensity inside the basal cisterns (black asterisk) with spread through the Sylvian fissure (white arrows) and the interhemispheric fissure (black arrow) towards the sulci of the convexity. B) 3D reconstruction of CT angiography of intracranial arteries: aneurysmal dilatations in both medial cerebral arteries and the confluence between the anterior cerebral artery and the right anterior communicating artery (black arrows).

SOLs corresponded to metastases (not known) in one case (1.25%), diffuse glioma (not known) in one case (1.25%), a pineal cyst (known) in one case (1.25%), and a cavernoma (known) in one case (1.25%). The four cases of infectious disease (5%) were inflammatory sinus diseases. The “other” group included the following: two cases (2.5%) of hydrocephaly (two instances of a single patient with known hydrocephaly and a malfunctioning ventriculoperitoneal shunt valve with worsening of the hydrocephaly), one patient (1.25%) with chronic subdural hygromas (also known) and one patient (1.25%) with emphysema of the muscle planes (with no known cause).

Instability, dizziness and/or vertigoSymptoms such as instability, dizziness and vertigo were grouped, with a total of 53 CT requests (10.5%): 17 (32.1%) in male patients and 36 (67.9%) in female patients, with a mean age of 66.5±16.6 years.

The results of the CT scans for this group of symptoms are summarised in Table 5. All the infarctions found in this group of patients (18; 33.9%), both acute and chronic, affected the posterior region. In addition, it must be added that one (1.9%) of the cases classified as normal by CT showed an acute infarction in the posterior region on MRI.

Results of emergency brain CT scans requested due to instability, dizziness or vertigo.

| Instability/dizziness/vertigo | Overall | Solitary | Associated with headache |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 30 (56.6%) | 20 | 10 |

| Ischaemic disease | 18 (33.9%) | 13 | 5 |

| • Acute infarctions | 2 (3.8%) | 2 | 0 |

| • Chronic infarctions | 2 (3.8%) | 2 | 0 |

| • Small-vessel lesions | 14 (26.3%) | 9 | 5 |

| Trauma | |||

| • Soft-tissue haematoma | 1 (1.9%) | 1 | 0 |

| SOL | 1 (1.9%) | 1 | 0 |

| Infectious disease | 1 (1.9%) | 1 | 0 |

| Inflammatory disease | 1 (1.9%) | 1 | 0 |

| Other | 1 (1.9%) | 1 | 0 |

SOL: space-occupying lesion.

It must also be remarked that no middle or inner ear disease was found in any of the cases.

The SOL found in this group corresponded to one cavernoma (1.9%). The infectious disease group featured one reported case (1.9%) of inflammatory sinus disease. The inflammatory disease group included one young patient (1.9%) with hypodense lesions suggestive of a multiple sclerosis-type demyelinating disease in the context. The "other" group included one patient (1.9%) diagnosed with moyamoya-like vasculopathy.

Altered level of consciousnessThis group included patients with syncope, decreased level of consciousness, agitation and disorientation. In this regard, it must be specified that no objective scale was routinely used; rather, CT scan requests in this subgroup were based on a subjective evaluation both by the physician attending to the emergency and by the family members who brought the patient to the emergency department. A total of 49 patients (9.7%) were included in this group; of these, 30 (61.2%) were male and 19 (38.85) were female, with a mean age of 73.9±15 years.

The results of the CT scans due to altered level of consciousness are shown in Table 6.

Results of emergency brain CT scans requested due to altered level of consciousness.

| Altered level of consciousness | Overall | Syncope | Agitation, disorientation | Decreased level of consciousness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 17 (34.7%) | 3 | 11 | 3 |

| Ischaemic disease | 25 (51%) | 8 | 14 | 3 |

| • Acute infarctions | 4 (8.2%) | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| • Chronic infarctions | 1 (2%) | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| • Small-vessel lesions | 20 (40.8%) | 6 | 11 | 3 |

| Non-traumatic haemorrhage | 2 (4.1%) | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| • Intraventricular haemorrhage | 1 (2%) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| • Combination | 1 (2%) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| SOL | 4 (8.2%) | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Other | 1 (2%) | 0 | 1 | 0 |

SOL: space-occupying lesion.

SOLs corresponded to one case (2%) of glioblastoma multiforme which was not known, one case (2%) of meningioma, one case (2%) of a dermoid cyst, and one case (2%) of an arachnoid cyst. The “other” group included one patient (2%) with a porencephalic cavity.

SeizuresFourteen (2.8%) of the requests were due to seizures; six (42.9%) were in male patients and eight (57.1%) were in female patients, with a mean age of 56.5±25.1 years.

Six (42.9%) of the scans were classified as normal. Trauma was found in two patients (14.3%): one case (7.15%) corresponded to a fracture and the other case (7.15%) corresponded to a parenchymal contusion.

In two other patients (14.3%), ischaemic disease was reported: one case (7.15%) of acute infarction and one case (7.15%) of chronic infarction.

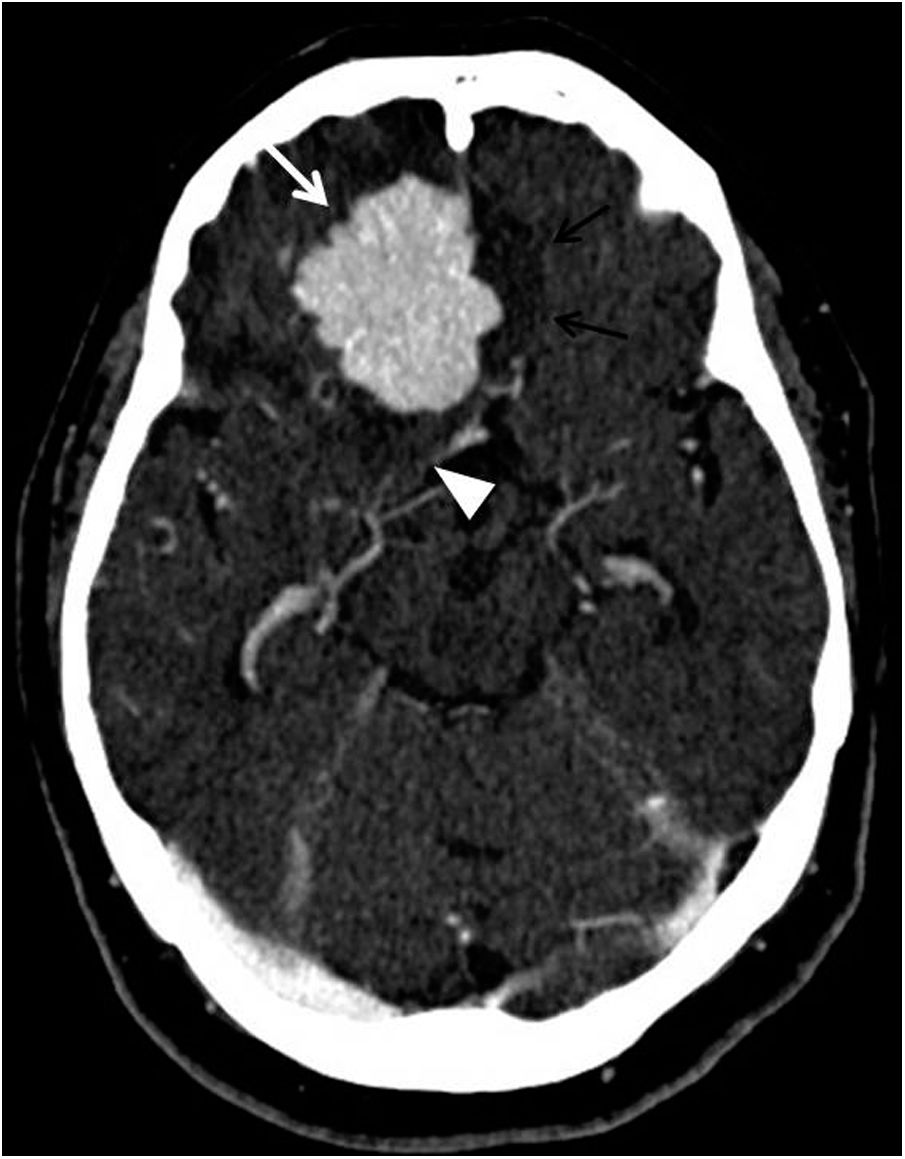

The SOL group included one case (7.15%) of a meningioma causing transtentorial herniation (Fig. 4). The inflammatory disease group included a patient with inflammatory arthritis of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) caused by crystals (7.15%). The “other” group included a known subependymal nodular heterotopia and an encephalocele (7.15% each).

CT scan of the skull with intravenous contrast, axial plane. A patient attending A&E for seizures was found to have a right frontobasal extra-axial space-occupying lesion, with well-defined lobulated margins and homogeneous contrast uptake, in relation to meningioma (white arrow), with vasogenic oedema in the neighbouring parenchyma (black double arrow) and deviation of the right uncus towards the suprasellar cistern (white arrow tip).

Visual disturbances, including decreased visual acuity and diplopia, accounted for 2% of the requests (10 patients). Of these, eight patients (80%) were women and two patients (20%) were men, with a mean age of 57.5±20.6 years.

Nine (90%) of the scans were considered normal and the remaining one (10%) showed small-vessel ischaemic lesions.

Psychiatric symptomsIn seven (1.4%) of the patients, the scan was performed due to psychiatric symptoms with the aim of ruling out brain damage. Five of the patients (71.4%) were female and two of them (28.6%) were male. The mean age was 65±17.1 years.

In four (57.1%) of these patients, the CT scans were normal; in one (14.3%) trauma (soft-tissue haematoma) was found and in another (14.3%) ischaemic disease (chronic infarction) was found.

In addition, in the last of the cases (14.3%) an SOL was discovered; this was not confirmed by histology, and as the patient had a history of cancer, the differential diagnosis was made between metastasis and glioblastoma multiforme.

Cranial nerve palsyFive of the requests (1%) were due to cranial nerve palsy; four (0.8%) were due to cranial nerve VII palsy, corresponding to peripheral paralysis, and one (0.2%) was due to cranial nerve VI palsy. Four (80%) of these patients were female and the other one (20%) was male. The mean age was 69.6±21.6 years.

Just one (20%) of the scans was normal. Postoperative changes were reported in one (20%) of the patients. All the others had ischaemic disease: two of them (40%) had small-vessel ischaemic lesions and one (20%) had chronic infarctions.

AmnesiaLastly, two patients came in with signs and symptoms of transient global amnesia (0.4%); both were men, with a mean age of 63.5±17.7 years.

Ischaemic disease was detected in both cases; one (50%) had chronic infarctions and the other (50%) had small-vessel lesions.

DiscussionA medical emergency is defined as an acute medical-surgical problem that endangers the patient’s life or any of the patient’s organs or functions, and therefore requires immediate medical attention.11,12

Brain CT scans represent an essential tool in the diagnosis of multiple neurological diseases, especially in acute situations in the emergency department, since they enable prompt evaluation of intracranial diseases and determination of the seriousness of the situation. These things, in turn, make it possible to screen patients who require emergency surgical treatment and distinguish them from those who can be managed with medical treatment or observation.2–5

The most common reasons for care in emergency departments include neurological emergencies, which account for 2.6–14% of all care according to studies recently conducted at Spanish hospitals.13,14 While neurological emergencies are many and varied, those most commonly reported in the scientific literature15–17 are traumatic brain injury, acute neurological deficit and headache. This was corroborated in this study, as those were also the reasons most commonly found in our sample (Table 1). In studies that only collect data on medical disease (and therefore not trauma), the next most common reason is epilepsy.14 However, in our sample, the next most common reasons were instability and altered level of consciousness, followed by seizures.

The most significant results of our study were that just 12% of brain CT scans requested by the emergency department corresponded to emergency acute intracranial disease and a large part (43.2%) of the remainder of the scans were completely normal. The premise that most brain CT scans requested by emergency departments in our setting do not show acute intracranial disease has already been set out in other previous studies similar to this one15,16 However, none of them have found such low rates of acute disease.

Although this study is merely descriptive and solely intended to reflect day-to-day realities at our hospital, not to assess the particular rationale for each of the tests performed, the percentage that we found of acute disease requiring urgent care was strikingly low. The limitations of assessing acute ischaemic disease by means of CT must be borne in mind: first, the study should be normal if the action times have been met, according to the Stroke Code; second, the difficulty of assessing the acuteness of small-vessel lesions; and, finally, the low sensitivity of CT for lesions in the posterior region.

These results could show an excessive use of brain CT in emergency departments, since, as was seen in our sample, a large part of the examinations were completely normal or showed findings with no significance for the patients, either overall or in any of the subgroups separately.

This could be due in part to the universally known reality of saturation of emergency departments,14 the growing trend towards defensive medicine due to increases in patient complaints, and, above all, the widespread availability of imaging tests at hospitals, which has brought about a recent rise in demand for emergency CT scans, especially of the head, resulting in saturation of radiology departments.

As mentioned previously, this study did not assess whether the CT scans performed during the study period were duly indicated or justified. This is a truly important question, both when tests are being requested by clinicians from the emergency department and when they are being accepted by the radiology department, and could be explored in subsequent studies.

Rationalisation of imaging tests in emergency departments is essential for preventing unnecessary patient overexposure to radiation, with not negligible doses, knowing that overuse thereof may eventually have adverse effects on patients' health which should not be overlooked.6,7,9 Furthermore, this affects not only the health of the population but also the health of the healthcare system, since unjustified imaging tests represent a substantial economic burden.6,9

For this reason, there are multiple guidelines for use in the emergency department on determining the need to perform an imaging test of the head. For traumatic brain injury, both the Canadian CT Head Rule (CCHR)18 and the New Orleans Criteria (NOC)19 are widely recognised and standardised guidelines for the evaluation of this type of patient in the emergency department. More recently, additional guidelines have appeared such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),9 the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study II (NEXUS II)20 and the Scandinavian Neurotrauma Committee (SNC) guidelines.21 It has been demonstrated that, with the adoption of these guidelines, it is possible to safely reduce the number of CT scans requested in patients with mild trauma,22 even in paediatric patients.23

Our hospital uses the Canadian CT Head Rule guidelines, but as shown in Table 2, many of the CT scans performed were completely normal despite using these guidelines. In addition, surprisingly, just 44.6% of scans showed acute trauma; considering that approximately 30% of these showed only soft-tissue haematomas, just 15.6% of the scans for this reason had genuinely significant trauma. The fact that trauma findings were so limited incited us to ponder whether the way in which the guidelines are being used is suitable or lacking. It might be interesting to conduct a comparative study of different scales in these patients.

Furthermore, the increasing tendency to repeat head CT in trauma patients was striking, despite the initial scan being normal, due to the risk of late complications, mainly subacute subdural haematomas. However, this risk has been shown to be insignificant,24 since 99.7% of repeat scans are negative following a normal initial CT scan.25 Therefore, scans should essentially be repeated in cases of altered level of consciousness or neurological deterioration compared to the patient’s previous state.26,27

Regarding all other non-traumatic neurological emergencies, there are no widely accepted guidelines for clinical action,28 so it would be necessary to develop action protocols for these types of situations that establish the indications for an emergency imaging test in the emergency department.

Some authors have identified a number of clinical criteria that predict the presence of abnormal findings on brain CT scans in non-trauma patients in the emergency department, which therefore can be used to screen patients who are candidates for CT scans. The following criteria have been proposed: age over 60 years, focal neurological deficit, altered mental state and headache accompanied by nausea and/or vomiting.29 Other authors, however, set the age at 70 years, propose nausea and/or vomiting accompanied, or not, by headache, and add the following criteria: history of malignancy and/or abnormal clotting profile.6 In this study, the authors did not support the routine use of CT scans in patients who presented only headache, vertigo, dizziness, drug use, blood pressure abnormalities or generalised symptoms, such as diffuse weakness in patients under 70 years of age.6 Another article proposed that the criterion of altered mental state be replaced with the Glasgow Coma Scale value (<14), this being an objective and more reproducible measure.28

In addition, it is important to take note of scoring systems from associations such as the Royal College of Radiologists, which recommend that only tests with repercussions for immediate patient management during medical shifts should be done.30

Finally, the “as low as reasonably achievable” (ALARA) principle must be followed.31 This involves not only avoiding examinations that are not justified or would not represent a change in the patient’s management, but also seeking to reduce the dose of radiation, despite the emergency nature of the situation, and having pre-established protocols in place in which the necessary parameters have been optimised.1

This study has several limitations. This was a retrospective study with results from a single centre and therefore from a particular geographic region. Consequently, the results are not broadly representative of the population. Another significant limitation was that our hospital is not a Stroke Code referral hospital. This might have accounted for the limited number of patients with parenchymal haematomas and acute infarctions in this study. Furthermore, it did not include a paediatric population, and so the prevalence of pathological findings in this population could not be examined.

In conclusion, most brain scans requested by emergency departments do not show disease that leads to changes in the patient's management. Emergency brain CT scans are an important tool, but their excessive use overloads radiology departments and exposes the population to unnecessary radiation.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for the integrity of the study: MNF and ESA.

- 2

Study concept: MNF, ESA and NSP.

- 3

Study design: MNF, ESA and NSP.

- 4

Data collection: MNF, ESA, NSP, CJB, CASV and SCE.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: MNF, ESA, NSP, CJB, CASV and SCE.

- 6

Statistical processing: MNF and ESA.

- 7

Literature search: MNF, ESA, NSP, CJB, CASV and SCE.

- 8

Drafting of the article: MNF and ESA.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: MNF, ESA, NSP, CJB, CASV and SCE.

- 10

Approval of the final version: MNF, ESA, NSP, CJB, CASV and SCE.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.