We present two cases of arterial gas embolism as a complication of percutaneous core-needle biopsy.

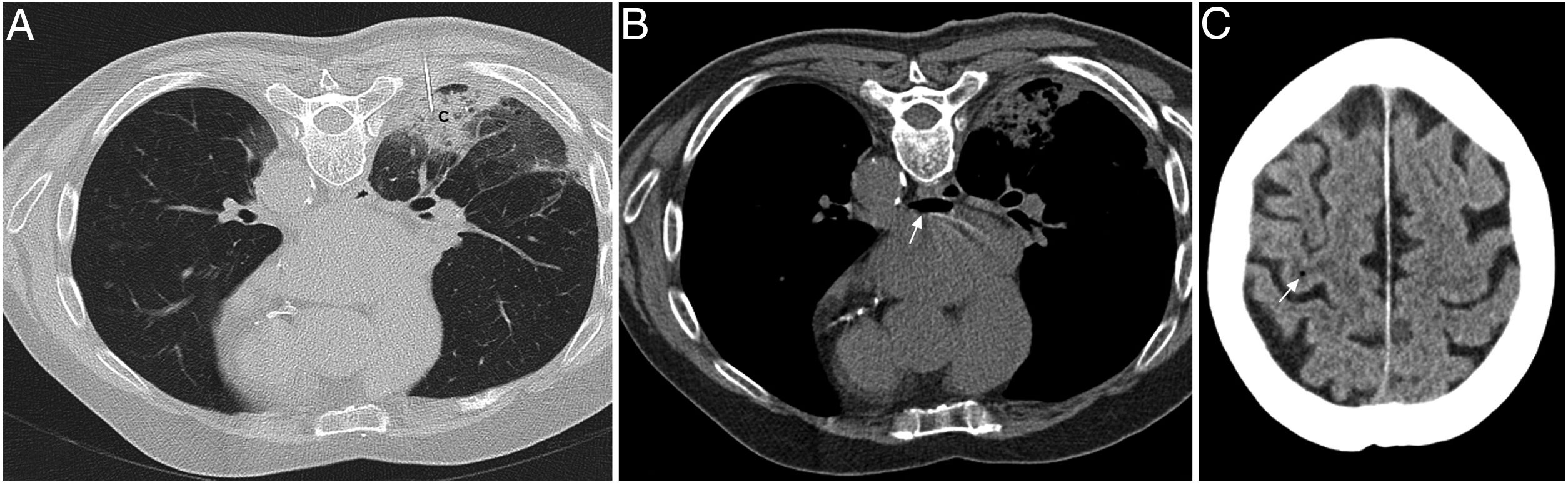

The first case was that of a 77-year-old man with pneumonia with poor progress who underwent biopsy of the consolidation in prone position, without complications. However, in the follow-up computed tomography (CT) scan, air was seen in the left atrium. One hour later he suddenly developed left hemiparesis, with brain CT showing an isolated gas bubble in the right convexity (Fig. 1). He made a full recovery. The histological diagnosis was organising pneumonia.

(A) Computed tomography (CT) in prone position during the biopsy, checking the position of the needle (coaxial 20 Gauge) inside the consolidation (C) in the right lower lobe. (B) Follow-up chest CT after biopsy in the same position, where gas is seen in the left atrium (arrow). (C) Brain CT performed one hour later, when the neurological deficit occurs, in which a small air bubble can be seen in the convexity (arrow).

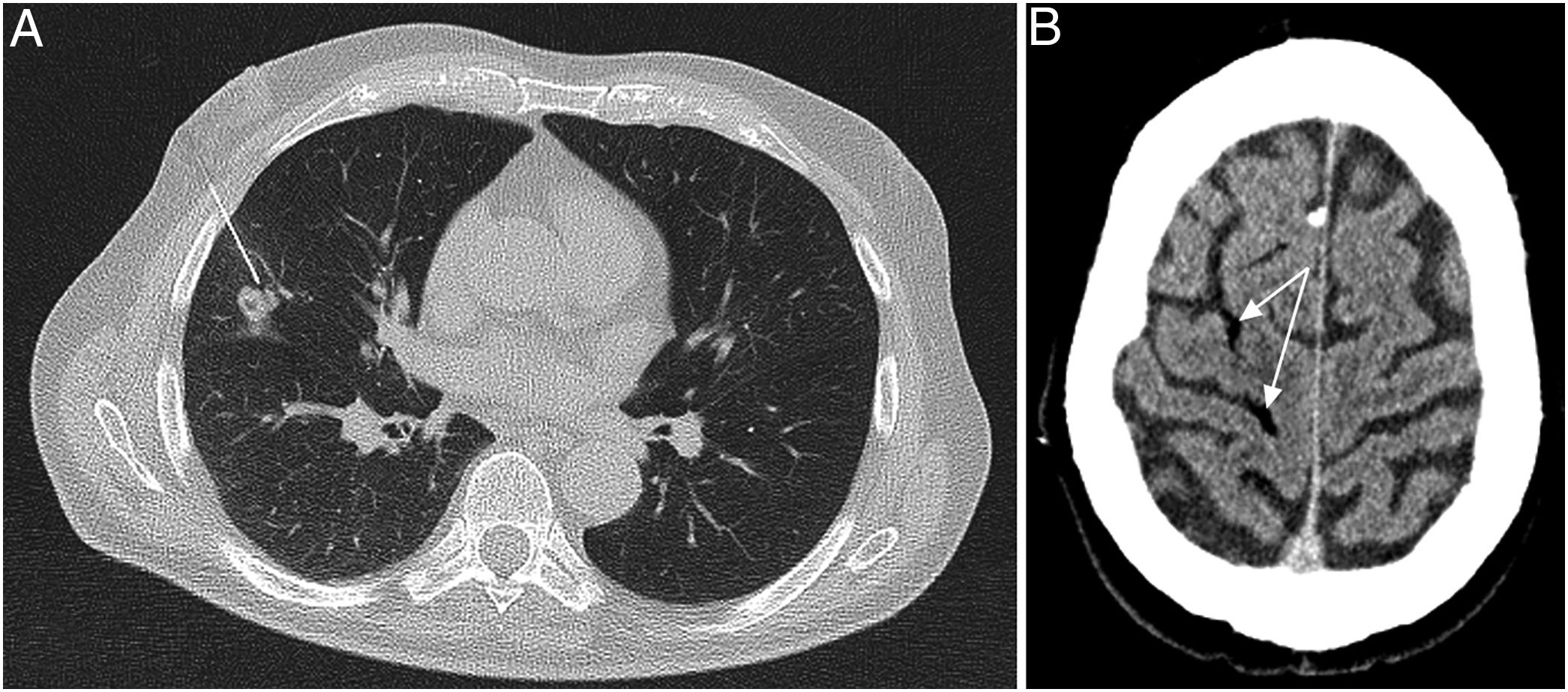

The second case was that of a 75-year-old man with a history of prostatic adenocarcinoma, with a rise in prostate-specific antigen in the previous year and lung nodules. A mid-lobe nodule biopsy was performed in supine position. After the procedure, the patient's level of consciousness decreased and he developed left hemiparesis, but he recovered spontaneously within 30minutes. Air was seen in cortical vessels in the brain CT (Fig. 2). The histological diagnosis was metastasis of prostatic adenocarcinoma.

Percutaneous lung biopsy is a common procedure in the assessment of pulmonary and mediastinal lesions. The most common complications include pneumothorax, haemorrhage and haemoptysis. Arterial gas embolism is a rare but potentially serious and fatal complication. The estimated incidence in the specialised literature is 0.02–0.4%, but it is probably higher, as there are asymptomatic cases which can remain undiagnosed.1

An arterial gas embolism is produced by entry of air into a pulmonary vein and the air then passing into the systemic circulation, either following direct communication between the atmospheric air and the vein through the needle, or from the needle creating a venous-bronchial fistula.

Any circumstance that increases the pressure gradient between the airway and the pulmonary vein can allow air into the vein, and this can occur because of an increase in the pressure in the airway (due to coughing or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) or a decrease in venous pressure (on inspiration).2

There is also a greater risk in biopsies performed in the prone position, when the lesions are located above the level of the left atrium, as this increases the pressure gradient between the airway and the pulmonary vein. To minimise this risk, whenever possible, the procedure should be performed with the patient in the lateral decubitus position on the side the lesion is located. The risk is also increased in biopsies of cavitated lesions or where the tissue is more friable, in lesions located more centrally or when making more passes is necessary.3

The most serious complication occurs when air reaches the cerebral and coronary arteries.

The clinical manifestations can be immediate or occur some minutes after the procedure and include neurological alterations (focal deficits, tremors or alterations in the level of consciousness), symptoms deriving from myocardial ischaemia (chest pain, hypotension, dyspnoea, arrhythmias or cardiorespiratory arrest) or even death.4 Some cases are however asymptomatic.

Our team recommends performing a follow-up CT after the procedure, not only of the biopsy area, but also of the heart and the great vessels, with the specific aim of looking for intra-arterial or intracardiac air. This measure would help diagnose the asymptomatic cases.

When a gas embolism is detected, the procedure should be stopped. The team should prepare to begin resuscitation manoeuvres, advise the cardiopulmonary resuscitation team, place the patient in the right lateral decubitus position (the air should remain in the left ventricular apex without entering the exit tract or the aorta), administer 100% oxygen and warn the hyperbaric chamber unit if possible.5

In conclusion, arterial gas embolism is a rare, unpredictable and unavoidable complication of percutaneous lung biopsy. However, as it is also potentially serious, we must have measures in place for early detection and be prepared to administer the appropriate initial treatment.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Reguero Llorente E, Alonso García E. Embolia gaseosa arterial tras biopsia pulmonar percutánea. Radiología. 2019;61:269–270.