The treatment of cancer has improved drastically in recent decades. Better understanding of tumour biology has enabled the development of new treatments, called targeted therapy. These drugs target specific signalling pathways that are necessary for the development of cancer. Immunotherapy is even more novel. These new agents can be classified into different groups, mainly according to their mechanism of action: VEGF inhibitors or anti-angiogenic agents, EGFR inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors, CTLA-4 inhibitors, or PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, etc.

All these new treatments are accompanied by new adverse effects that radiologists need to know. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of targeted therapies and knowing their adverse effects are vital to imaging assessment and ensuring appropriate treatment.

El tratamiento del cáncer ha avanzado drásticamente en las últimas décadas. Un mayor conocimiento de la biología tumoral ha propiciado el desarrollo de nuevos fármacos anticancerígenos, llamados “terapias dirigidas”. Estos fármacos tienen como diana vías de señalización específicas necesarias para el desarrollo del cáncer. Más novedosa es aún la inmunoterapia. Estos nuevos agentes se pueden clasificar en diferentes grupos, principalmente según su mecanismo de acción: inhibidores de VEGF o antiangiogénicos, inhibidores de EGFR, inhibidores de mTOR, inhibidores de CTLA-4, inhibidores de PD-1/PD-L1, etc.

Todas estas nuevas terapias traen consigo nuevos efectos adversos que el radiólogo debe conocer. Entender el mecanismo molecular de las terapias dirigidas y reconocer sus efectos adversos es esencial para una correcta valoración radiológica y para proporcionar un tratamiento apropiado.

Much of a radiologist's work nowadays is taken up with oncological radiology. Cancer treatment has advanced dramatically in the last twenty to thirty years. Thanks to a greater understanding of tumour biology, new drugs have been developed for the treatment of cancer which come under the term “targeted therapies” (TT). Although the cytotoxic agents of conventional chemotherapy inhibit cell division and target rapidly proliferating cells, TT target specific signalling pathways necessary for the cancer's development. As the targets of these two groups of drugs are different, it is not surprising that the adverse effects (AE) also differ.1

Immunotherapy is an even more novel treatment, which helps the immune system to halt cancer. Immunomodulatory monoclonal antibodies (mAb) are the newest immunotherapy agents, known as “immune checkpoint inhibitors” (ICI). This therapy uses preformed mAb directed against molecular targets on the surface of T cells, to regulate T-cell activation. This new immunomodulatory approach to treating cancer is accompanied by new treatment-related AE, which come under the term “immune-related adverse events”.2

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has now approved over 90 drugs for targeting different types of cancer.3 They are classified into different groups, generally according to their mechanism of action. Each group is associated with specific AE, and although some can be understood by their mechanism of action, the cause of others remains unknown.

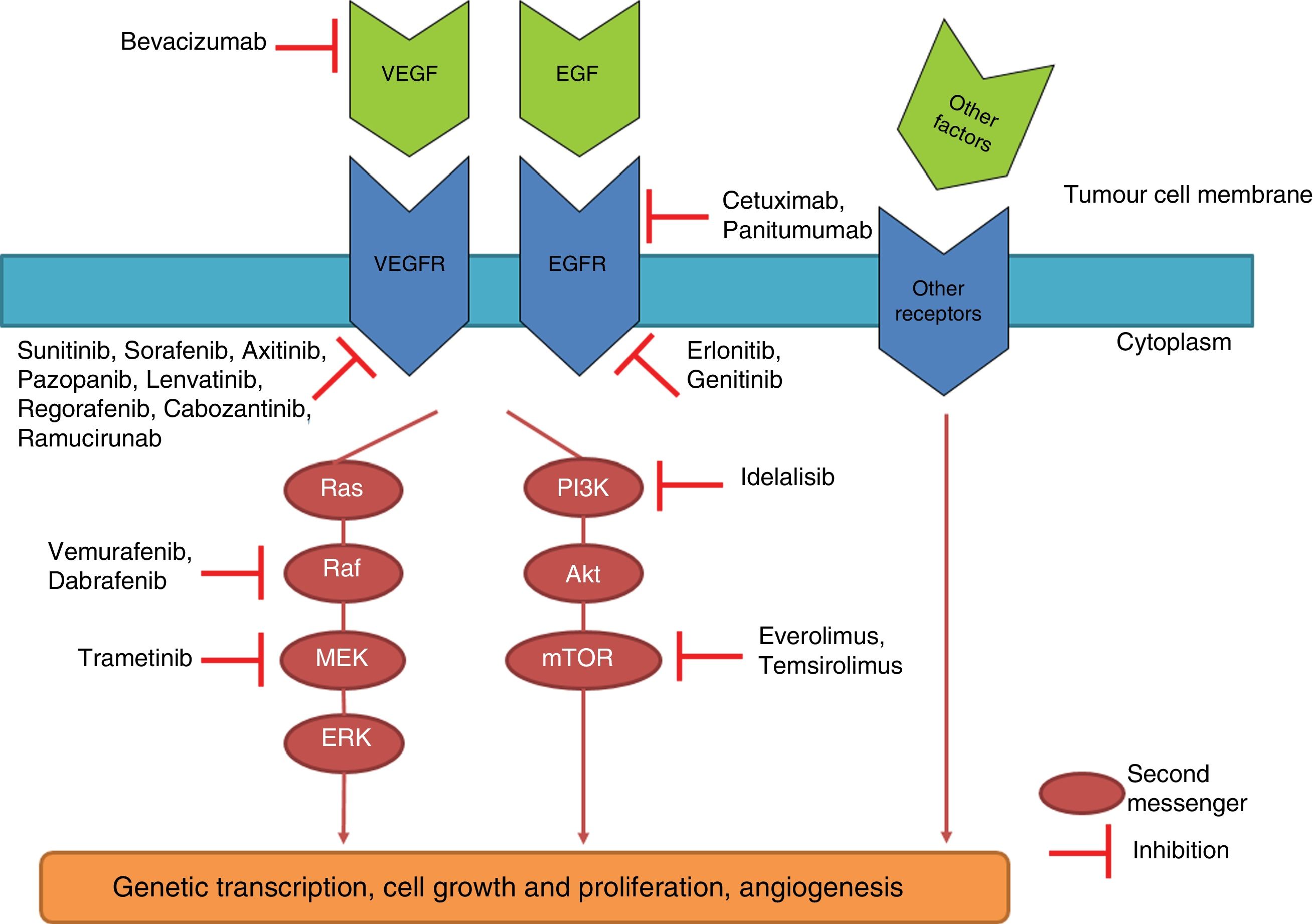

TT drugs are usually also classified into monoclonal antibodies (ending in – mab) and small molecule inhibitors (ending in – ib). The former target specific antigens or receptors on the cell surface. The latter, on the other hand, interact with intracellular targets. The latter group includes tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI). Tyrosine kinases (TK) are a group of enzymes belonging to the protein kinase group, 58 of which are of the receptor type and 32 non-receptors within the human genome.4 TK receptors are transmembrane molecules which are activated by a ligand (e.g. epidermal growth factor or EGF, vascular endothelial growth factor or VEGF, etc.) with the extracellular domain of the receptor. The interaction of the ligand with the receptor causes the activation or phosphorylation of its intracellular domain, which phosphorylates different intracellular molecules called “second messengers”, which instruct the cell to grow and divide. When, due to a mutation or over-expression, the activity of TK becomes excessive, cancer can develop and be accompanied by distinctive characteristics, depending on the type of cancer, such as uncontrolled growth, invasion and neovascularisation. TKI prevent phosphorylation of second messengers, interrupting intracellular signalling5 (Fig. 1).

Diagram of different intracellular molecular pathways and the mechanism of action of some targeted drugs. Binding of different antigens or growth factors to receptors on the cell membranes activates different intracellular pathways which, depending on the type of cancer, can end up causing uncontrolled cell growth, invasion and neovascularisation. The medications shown here inhibit these signalling cascades at different points.

TT-related toxicity can manifest through numerous symptoms and can be graded according to common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE v.5.0)6: grade 1 (mild), grade 2 (moderate), grade 3 (serious), grade 4 (life-threatening) and grade 5 (death). In some cases, withdrawing the drug is sufficient to prevent greater toxicity or associated complications. In mild cases, the chosen approach may be to “wait and see”.

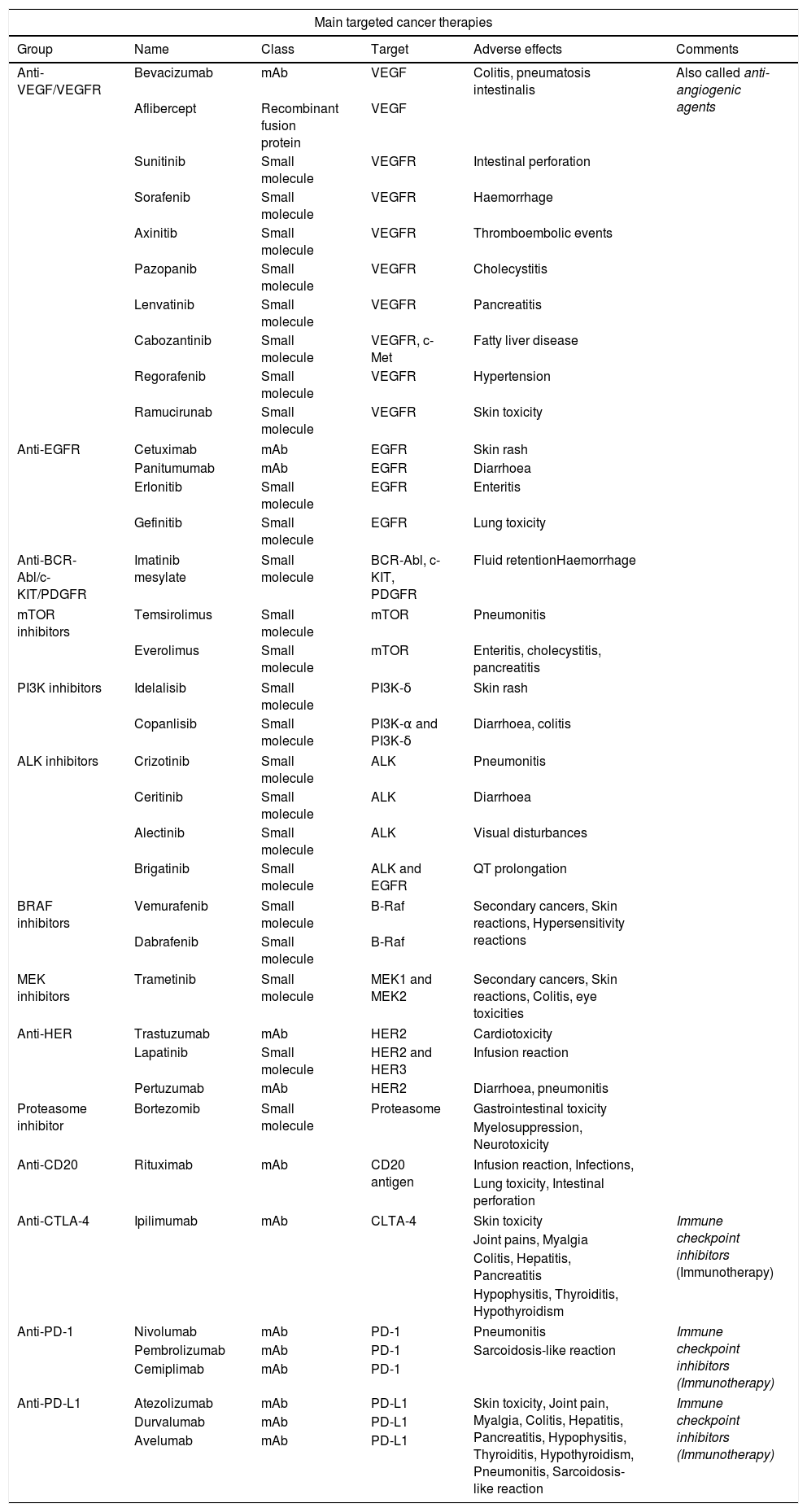

In this paper, we analyse the different groups of TT and their AE, with the emphasis on those most represented in radiology. A summary is provided in Table 1.

Summary of the main targeted cancer therapies.

| Main targeted cancer therapies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Name | Class | Target | Adverse effects | Comments |

| Anti-VEGF/VEGFR | Bevacizumab | mAb | VEGF | Colitis, pneumatosis intestinalis | Also called anti-angiogenic agents |

| Aflibercept | Recombinant fusion protein | VEGF | |||

| Sunitinib | Small molecule | VEGFR | Intestinal perforation | ||

| Sorafenib | Small molecule | VEGFR | Haemorrhage | ||

| Axinitib | Small molecule | VEGFR | Thromboembolic events | ||

| Pazopanib | Small molecule | VEGFR | Cholecystitis | ||

| Lenvatinib | Small molecule | VEGFR | Pancreatitis | ||

| Cabozantinib | Small molecule | VEGFR, c-Met | Fatty liver disease | ||

| Regorafenib | Small molecule | VEGFR | Hypertension | ||

| Ramucirunab | Small molecule | VEGFR | Skin toxicity | ||

| Anti-EGFR | Cetuximab | mAb | EGFR | Skin rash | |

| Panitumumab | mAb | EGFR | Diarrhoea | ||

| Erlonitib | Small molecule | EGFR | Enteritis | ||

| Gefinitib | Small molecule | EGFR | Lung toxicity | ||

| Anti-BCR-Abl/c-KIT/PDGFR | Imatinib mesylate | Small molecule | BCR-Abl, c-KIT, PDGFR | Fluid retentionHaemorrhage | |

| mTOR inhibitors | Temsirolimus | Small molecule | mTOR | Pneumonitis | |

| Everolimus | Small molecule | mTOR | Enteritis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis | ||

| PI3K inhibitors | Idelalisib | Small molecule | PI3K-δ | Skin rash | |

| Copanlisib | Small molecule | PI3K-α and PI3K-δ | Diarrhoea, colitis | ||

| ALK inhibitors | Crizotinib | Small molecule | ALK | Pneumonitis | |

| Ceritinib | Small molecule | ALK | Diarrhoea | ||

| Alectinib | Small molecule | ALK | Visual disturbances | ||

| Brigatinib | Small molecule | ALK and EGFR | QT prolongation | ||

| BRAF inhibitors | Vemurafenib | Small molecule | B-Raf | Secondary cancers, Skin reactions, Hypersensitivity reactions | |

| Dabrafenib | Small molecule | B-Raf | |||

| MEK inhibitors | Trametinib | Small molecule | MEK1 and MEK2 | Secondary cancers, Skin reactions, Colitis, eye toxicities | |

| Anti-HER | Trastuzumab | mAb | HER2 | Cardiotoxicity | |

| Lapatinib | Small molecule | HER2 and HER3 | Infusion reaction | ||

| Pertuzumab | mAb | HER2 | Diarrhoea, pneumonitis | ||

| Proteasome inhibitor | Bortezomib | Small molecule | Proteasome | Gastrointestinal toxicity | |

| Myelosuppression, Neurotoxicity | |||||

| Anti-CD20 | Rituximab | mAb | CD20 antigen | Infusion reaction, Infections, | |

| Lung toxicity, Intestinal perforation | |||||

| Anti-CTLA-4 | Ipilimumab | mAb | CLTA-4 | Skin toxicity | Immune checkpoint inhibitors (Immunotherapy) |

| Joint pains, Myalgia | |||||

| Colitis, Hepatitis, Pancreatitis | |||||

| Hypophysitis, Thyroiditis, Hypothyroidism | |||||

| Anti-PD-1 | Nivolumab | mAb | PD-1 | Pneumonitis | Immune checkpoint inhibitors (Immunotherapy) |

| Pembrolizumab | mAb | PD-1 | Sarcoidosis-like reaction | ||

| Cemiplimab | mAb | PD-1 | |||

| Anti-PD-L1 | Atezolizumab | mAb | PD-L1 | Skin toxicity, Joint pain, Myalgia, Colitis, Hepatitis, Pancreatitis, Hypophysitis, Thyroiditis, Hypothyroidism, Pneumonitis, Sarcoidosis-like reaction | Immune checkpoint inhibitors (Immunotherapy) |

| Durvalumab | mAb | PD-L1 | |||

| Avelumab | mAb | PD-L1 | |||

mAb: monoclonal antibody; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGFR: vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; EGFR: endothelial growth factor receptor; mTORi: mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitor; PDGFR: platelet-derived growth factor receptor; PI3K: phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase; ALK: anaplastic lymphoma kinase; B-Raf: protein encoded by the BRAF gene (named after the RAF oncogene: rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma); MEK: mitogen-activated protein kinase or MAP2K or MAPKK; HER: human epidermal growth factor receptor; CTLA-4: cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; PD-1: programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1: programmed cell death protein-1 ligand.

VEGF is a pro-angiogenic factor which binds to multiple endothelial receptors, mainly VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2, and triggers a cascade of intracellular interactions that stimulate endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis. VEGF plays a fundamental role in a number of different physiological processes, such as wound healing and maintaining the integrity of the mucosa. Inhibition of VEGF can therefore lead to an unintended systemic decrease in angiogenesis and blood flow, causing ischaemia or poor wound healing.3 For that reason, drugs in this group are also known as “anti-angiogenic” agents.

The FDA-approved anti-VEGF agents are the following: bevacizumab (mAb), ziv-aflibercept (a recombinant fusion protein which acts as a receptor that binds to VEGF-A and VEGF-B), and sunitinib, sorafenib, axitinib, pazopanib, lenvatinib, regorafenib, cabozantinib and ramucirumab (TKI).

Adverse effects:

- •

Skin toxicity: although the most common AE, radiologists do not play a significant role in the diagnosis.

- •

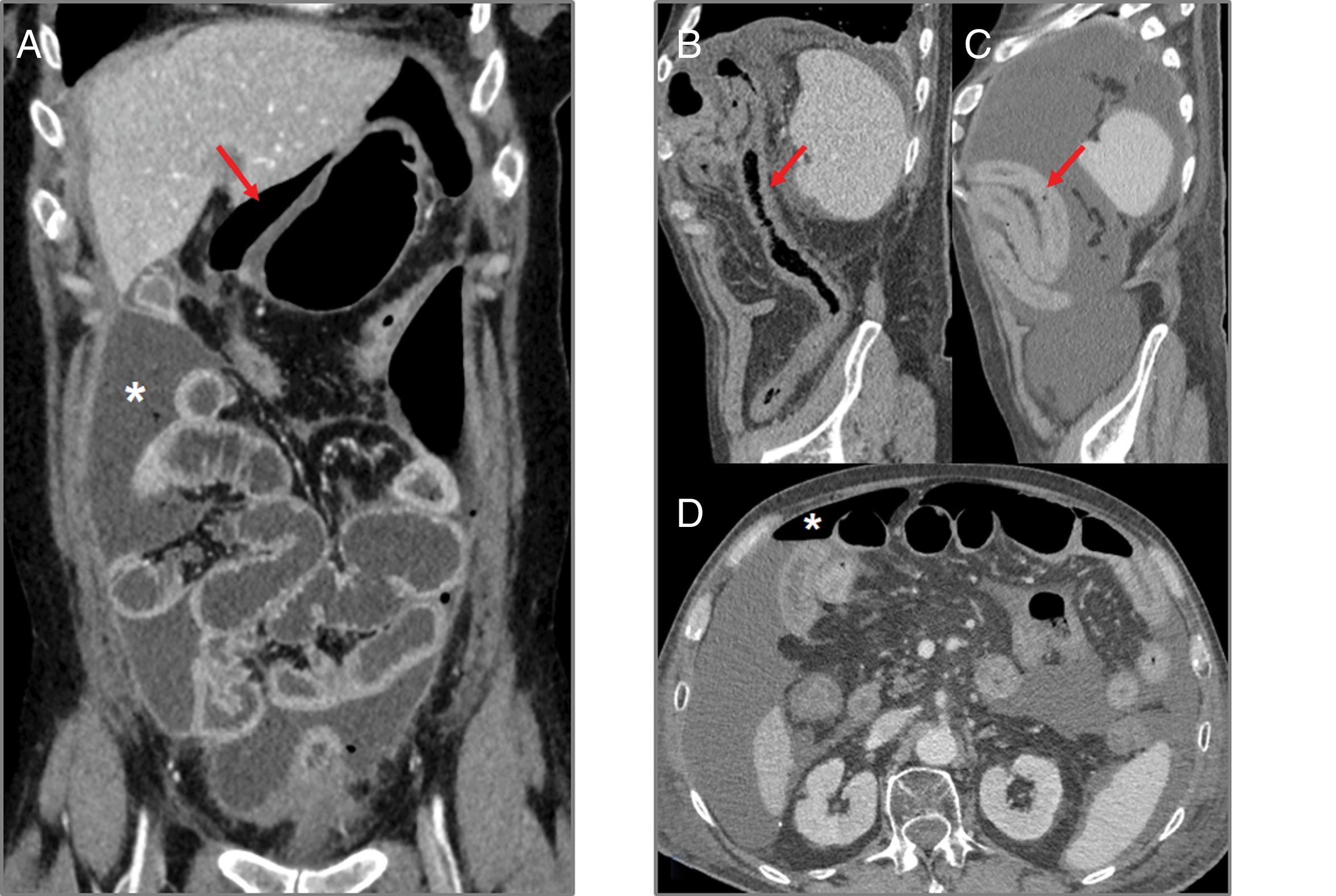

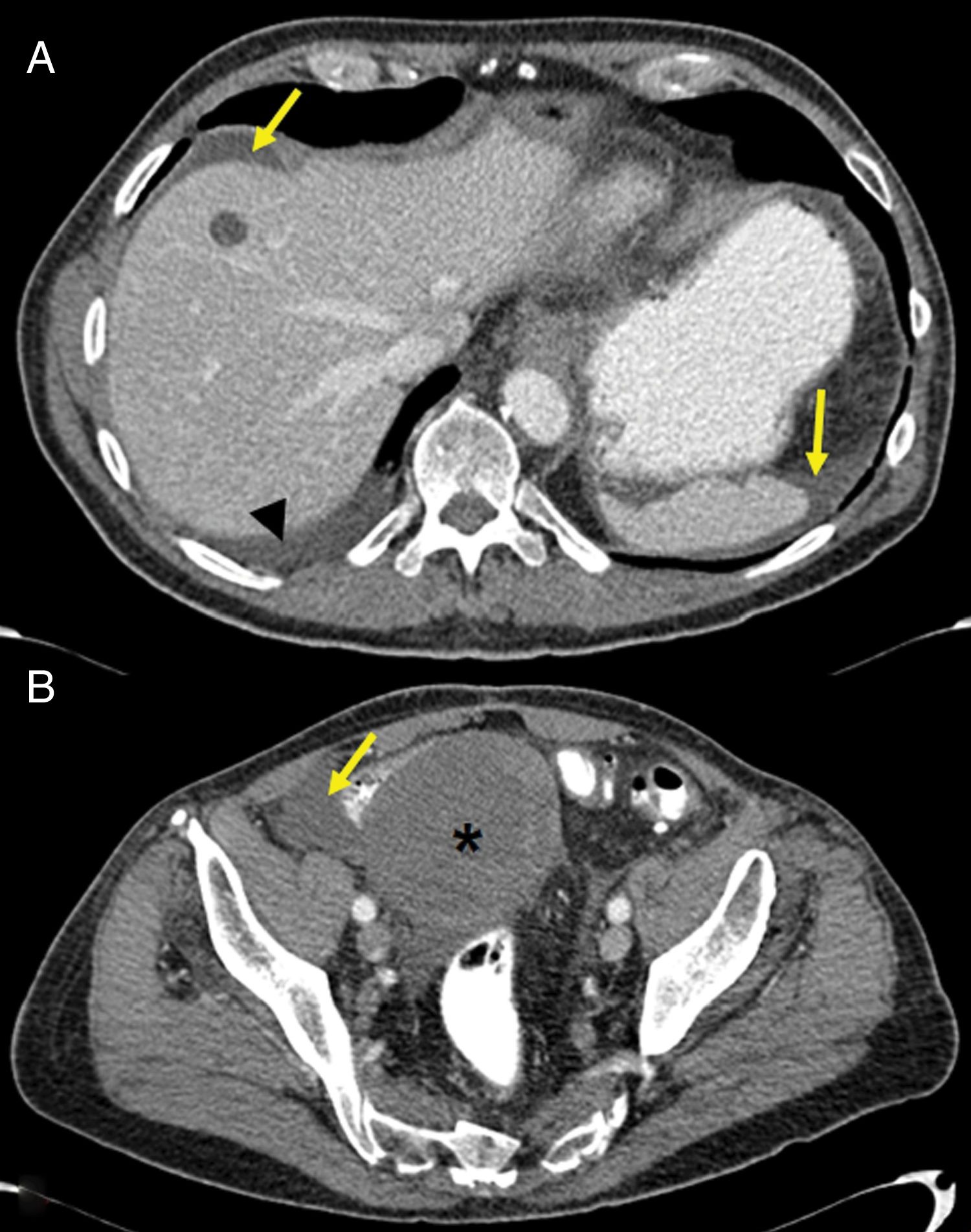

Intestinal perforation (Fig. 2): bevacizumab, sorafenib and sunitinib are known to be associated with intestinal perforation, apparently caused by their interactions with the microvasculature, causing ischaemia and thrombosis of the vessels.7,8 The risk of perforation is also greater in colon cancer and renal cell carcinoma.7,9 In computed tomography (CT), intestinal perforation may be seen as pneumoperitoneum, but also as intra-abdominal free fluid, discontinuity in the intestinal wall, thickening of the intestinal wall and abscess formation.7,9 Intestinal perforation primarily occurs during the first six months of treatment.8

Figure 2.Intestinal perforation associated with VEGF-targeted therapy. Case 1 (A): 46-year-old woman with ovarian cancer being treated with bevacizumab. Computed tomography (CT) shows pneumoperitoneum (arrow) and free fluid (star) in the context of an intestinal obstruction. This obstruction was not very serious; the intestinal wall was probably weakened due to bevacizumab. Case 2 (B–D): 71-year-old male on second-line treatment with a paclitaxel-ramucirumab regimen for metastatic recurrence of gastric adenocarcinoma. (B) CT obtained during admission due to pyrexia and abdominal pain after the 2nd cycle: new-onset ascites and thickening of the transverse, descending and sigmoid colon in relation to colitis (arrow). Corticosteroid treatment and a watch-and-wait approach adopted as the patient showed clinical improvement. (C and D) CT of abdomen and pelvis performed one week later due to clinical worsening: persistence of the colitis (arrow) observed, as well as new-onset pneumoperitoneum (star) due to intestinal perforation.

- •

Intestinal pneumatosis: the decrease in the capillaries in the intestinal wall and the reduction of endothelial healing leads to microperforations and the entry of air into the wall.10 CT findings include air in the intestinal wall with possible pneumoperitoneum and mesenteric or portal gas.9 Pneumatosis may be seen in asymptomatic patients, but the clinician should always be notified.

- •

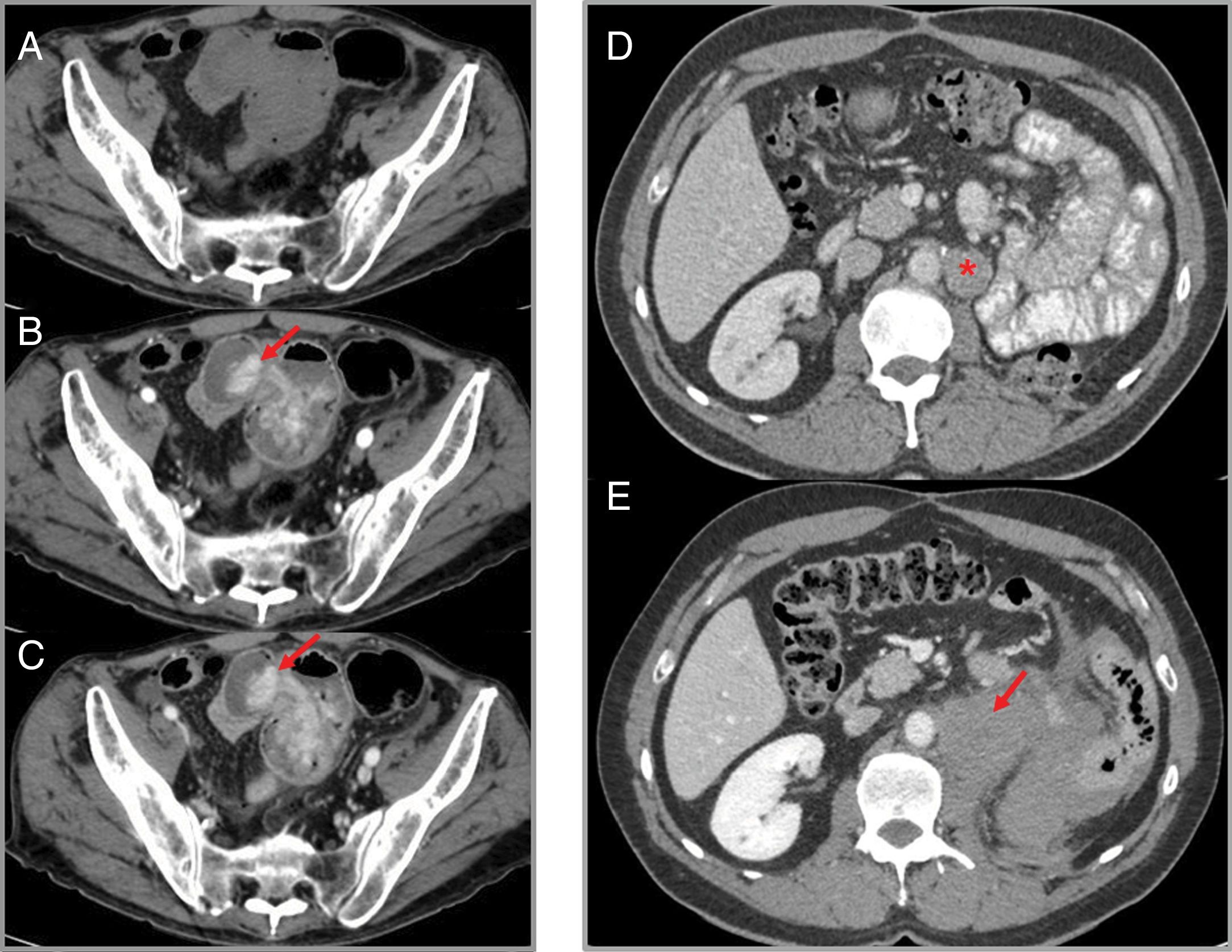

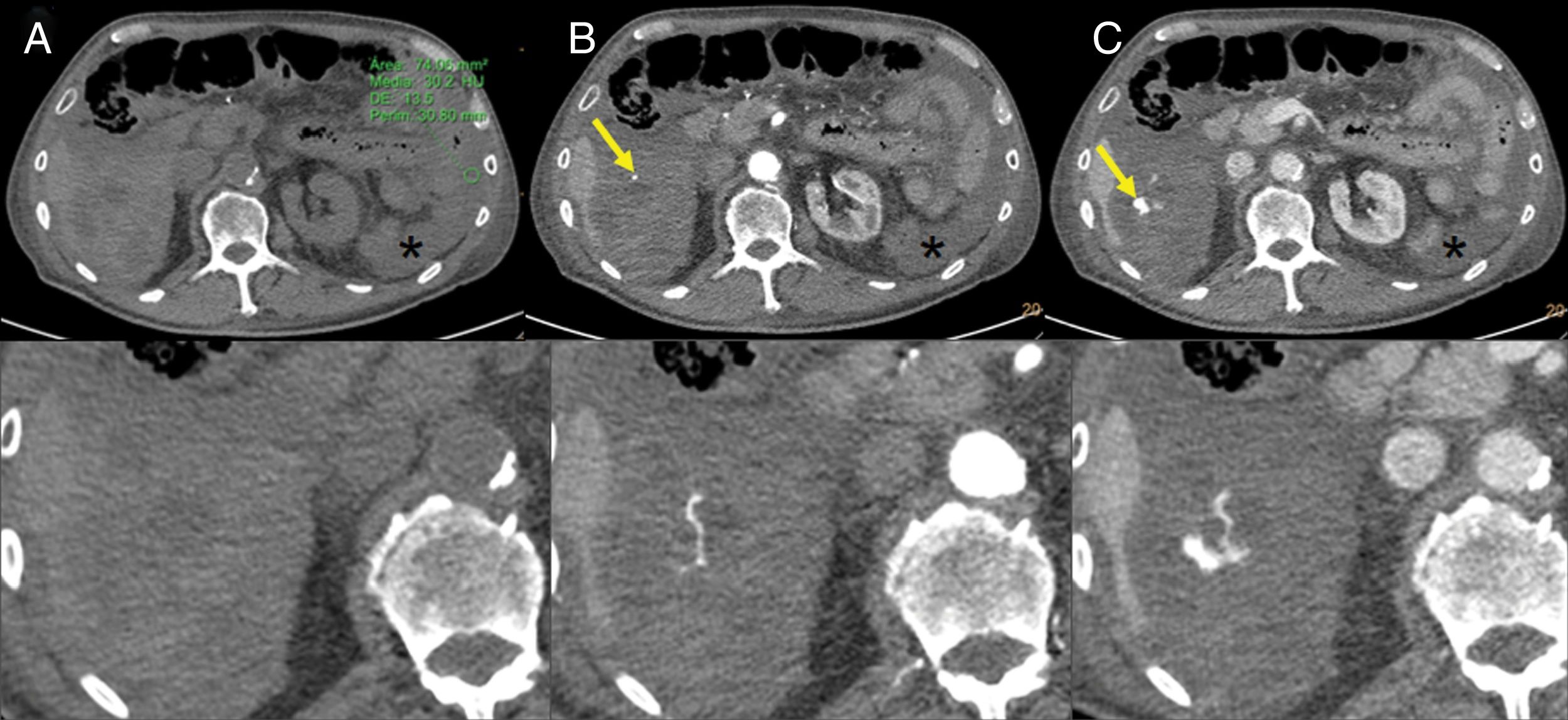

Haemorrhage: this has been described in up to 30% of patients with cancers treated with anti-VEGF drugs, with severe bleeding in 5% of cases.11 While epistaxis is the most common haemorrhagic manifestation, radiologically relevant forms are gastrointestinal bleeding (Fig. 3), intratumoral haemorrhage (Fig. 3) and haemoptysis. A meta-analysis of 23 studies analysing the risk of bleeding in patients treated with sunitinib and sorafenib shows that the risk is doubled in these patients.12

Figure 3.Haemorrhage associated with VEGF-targeted therapy. Case 1 (A–C): intestinal bleeding in a patient with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sorafenib. Computed tomography (CT) shows a hyperdense area in an ileal loop in the arterial phase (B) which increases in the venous phase (C), suggestive of active bleeding (arrows). (A) Phase without intravenous contrast. Case 2 (D and E): patient with advanced renal cell carcinoma on treatment with sunitinib in whom retroperitoneal haemorrhage is detected. (D) Left para-aortic lymph node metastasis (star) can be identified. (E) A later CT scan shows retroperitoneal bleeding (arrow) originating from the metastatic lymphadenopathy.

- •

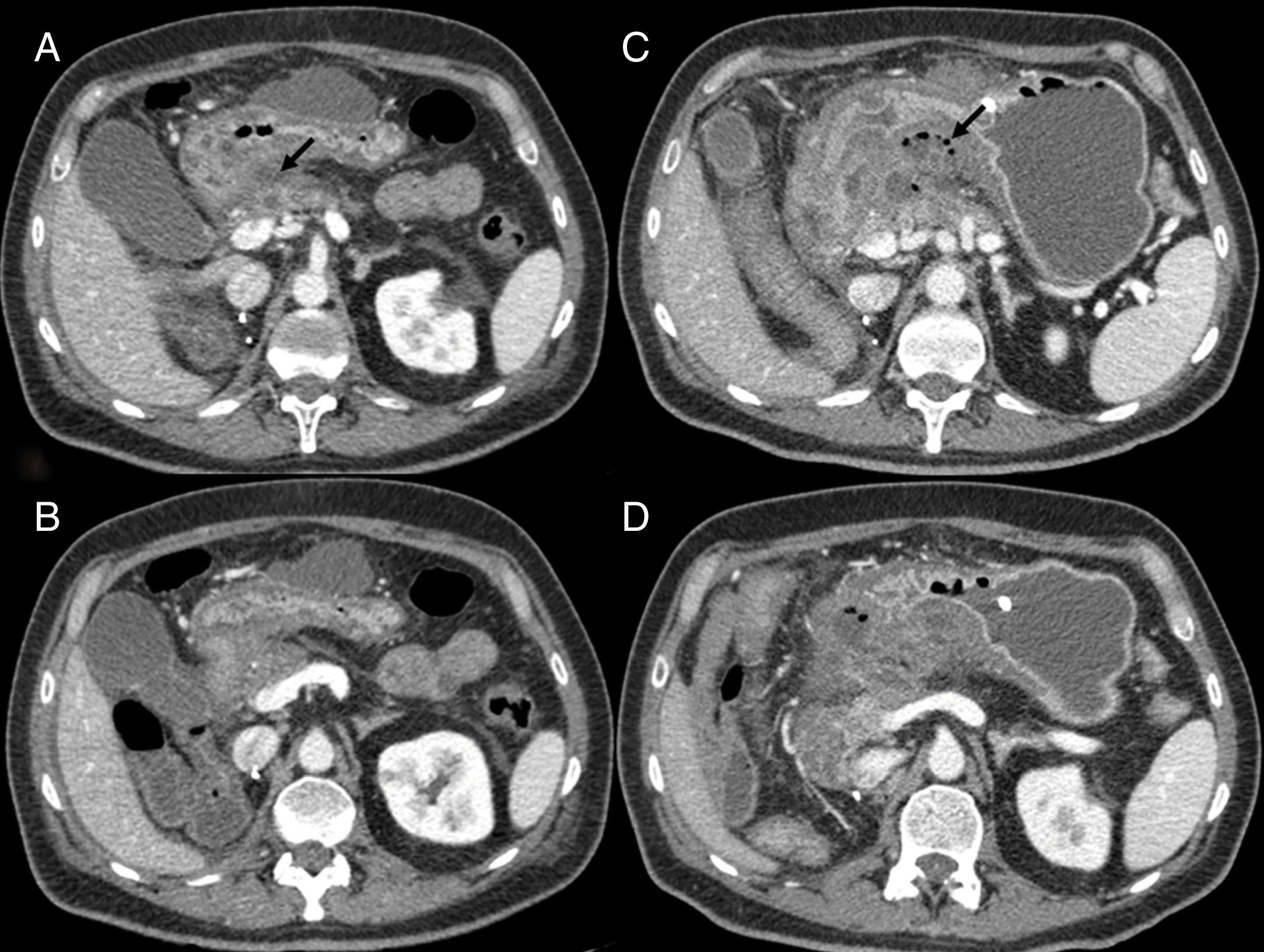

Pancreatitis (Fig. 4): pancreatitis induced by anti-angiogenic agents is rare. It tends to be mild and focal, with no fat necrosis or associated fluid collections.13 Clinical pancreatitis with no imaging findings is also possible.14

Figure 4.Pancreatitis in a 50-year-old man with stage IV renal cell carcinoma, treated with sunitinib. (A and B) Computed tomography (CT) shows densification of fat and peripancreatic fluid, as well as a small collection (arrow). No association between the pancreatitis and the drug is suspected and the patient continues on the same treatment. (C and D) CT scan of the same patient one month later, with multiple collections with air bubbles inside (arrow). On this occasion, sunitinib-induced necrotic pancreatitis is diagnosed and second-line treatment with axitinib is started.

- •

Other abdominal complications associated with this drug group are fatty liver disease, cholecystitis, enteritis and diarrhoea.

- •

Arterial thromboembolic events: the risk of cardiac and cerebrovascular thromboembolic events, and the formation of arterial thrombi, is increased in patients given anti-VEGF treatment.14,15 Although the mechanism is not fully understood, the role of VEGF in maintaining the integrity of the vascular endothelium is thought to be related in some way.14,15 In a meta-analysis which included different clinical trials with sunitinib and sorafenib to establish the risk of thromboembolic events, a three-fold increased risk of developing an arterial thromboembolic event was identified in these patients compared to the control group. They found that the risk did not depend on the type of anti-VEGF used or the type of cancer.16 In imaging studies, arterial thromboembolism will be seen as a filling defect in the affected vessel.

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a member of the ErbB family of TK receptors, is a cell surface molecule whose activation triggers an intracellular signalling cascade which affects invasion, apoptosis and angiogenesis. This factor is expressed in almost all normal cells of the human body, particularly in those of epithelial origin such as the skin, liver and gastrointestinal tract.17 As a consequence, the most typical AE in EGFR inhibitors are skin rash and diarrhoea.17 Other possible AE are enteritis and lung toxicity.14 These AE occur mainly as a result of the interruption of the EGFR's physiological effects of wall maintenance and repair of tissues of epithelial origin.

At present, the EGFR inhibitors with the greatest clinical application are the mAb cetuximab and panitunumab and the TKI erlotinib and gefitinib.3,17

BCR-Abl/c-KIT/PDGFR inhibitorsThis group includes the drug imatinib mesylate, a selective inhibitor of the BCR-ABL, c-KIT and PDG TK receptors.3 This binds competitively to the TK domain in ABL, c-KIT and PDGFR and inhibits the protein and its end functions, such as cell proliferation. It is mainly used in the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST).

Adverse effects:

- •

Skin rash and gastrointestinal toxicity (diarrhoea and vomiting) are the main AE.

- •

Fluid retention: mild periorbital or peripheral oedema is common, but radiologically, pleural and pericardial effusion, pulmonary oedema, mesenteric vascular congestion, ascites (Fig. 5) and thickening of the skin can be found.18,19 Therefore, in patients treated with imatinib, if ascites appears on CT, the drug-related AE should be considered as more likely than tumour progression.

- •

Intratumoral and peritumoral haemorrhage: this can occur in up to 5% of cancers treated with imatinib, especially in bulky GIST.18 Radiological findings include fluid-fluid levels in the tumour and intra- or retroperitoneal free fluid, which is due to haemoperitoneum (Fig. 6). These findings should not be misinterpreted as tumour progression, despite an increase in the size or density of the tumour on the CT scan. The Choi response criteria were developed specifically to evaluate tumour response in patients with GIST treated with imatinib.18,20

Figure 6.Intratumoral haemorrhage in a patient with a gastrointestinal stromal tumour treated with imatinib. Abdominal CT angiography showing extravasation of intravenous contrast in the arterial phase (B) which increases in the venous phase (C), probably secondary to active intralesional arterial haemorrhage in the perihepatic implant (arrows). Haemoperitoneum (stars) can also be seen. (A) Phase without contrast (shows a region of interest in the left flank with an average density of 30 UH).

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a member of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase protein kinase family. It participates in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling pathway, regulating different cell processes such as cell growth, cell proliferation, cell survival, protein synthesis and transcription. Abnormal activation of first PI3K and subsequently mTOR causes angiogenesis and cell proliferation. Everolimus and temsirolimus are two mTOR inhibitors (mTORi). Everolimus is approved for the treatment of breast, pancreatic, gastric, lung and renal cancers and for subependymal giant cell astrocytoma. Temsirolimus is approved in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma.3

- •

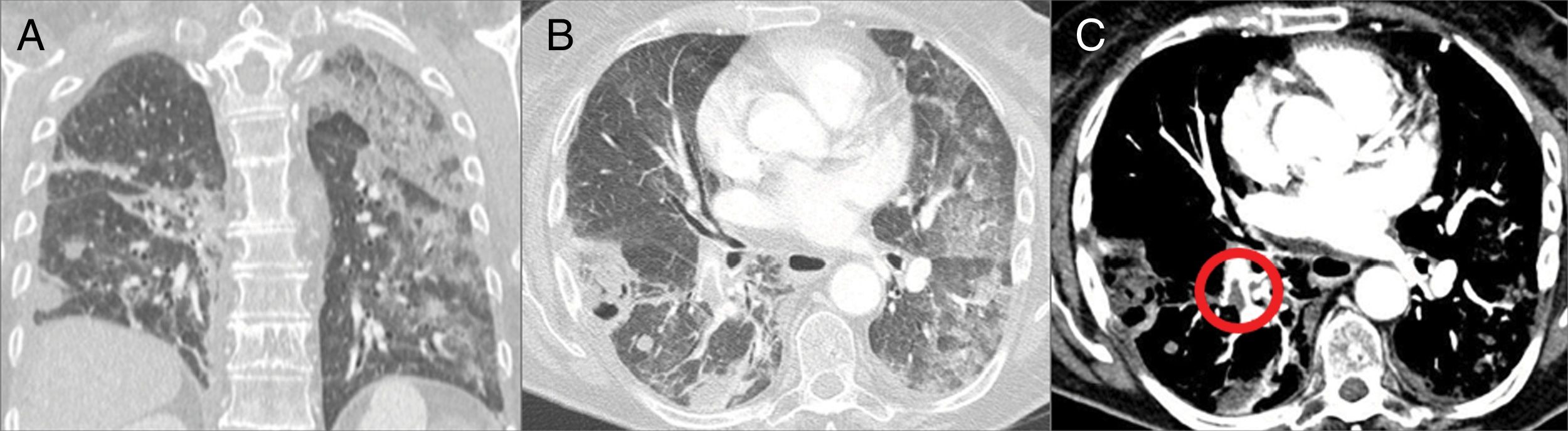

Pneumonitis: lung toxicity, and more specifically pneumonitis, is one of the most serious mTORi-related complications and the most relevant in this group from a radiologist's point of view. Lung toxicity appears to be more common when mTORi are used to treat cancer than in transplant regimens. This would seem to be due to the dose administered and the fact that cancer patients receive more frequent radiological monitoring.21 Pneumonitis tends to occur from two to six months after starting treatment.21 In the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma, it is more common with everolimus than with temsirolimus.22

- •

Radiologically, the most common findings on CT are ground-glass opacity and focal consolidation21 (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.79-year-old woman with stage IV renal cell carcinoma, on third-line treatment with everolimus. (A and B) Computed tomography shows large areas of ground glass opacity in both lung fields with a small area of consolidation in relation to everolimus-induced pneumonitis. (C) In the mediastinal window a pulmonary thromboembolism can be seen in the right lower lobar artery (circle).

- •

Around a quarter of patients are asymptomatic,22 and the most common symptoms are pyrexia, dyspnoea, cough, night sweats and fatigue. Pulmonary function tests are recommended before starting treatment in patients with baseline respiratory symptoms and if normal, treatment may be started.21 Lung toxicity associated with mTORi therapy should be a diagnosis of exclusion. Monitoring of respiratory symptoms in these patients is essential, and in the case of suspected pneumonitis, pulmonary function tests and radiological assessment are necessary.21

- •

Although the mechanism of action is not fully understood, the possibilities include direct damage to alveolar structures, the formation of immunological haptens and direct immune response to the drugs.21

- •

Other possible AE are dermatological, haematological (anaemia, thrombocytopenia), metabolic disorders (hyperlipidaemia, hypercholesterolaemia), hypertension, proteinuria, etc.21 Imaging techniques are not so important in these cases as in pneumonitis.

This group also includes drugs that act on the PI3k/AKT/mTOR signalling pathway. Idelalisib and copanlisib are PI3Ki approved by the FDA for the treatment of blood cancers.3

Idelalisib is a phosphoinositol 3-kinase δ (PI3K-δ) inhibitor, which prevents signalling of the receptor antigen in B and T lymphocytes. Copanlisib primarily inhibits PI3K-α and PI3K-δ. These agents have been associated with pneumonitis, colitis, liver toxicity, hypertension and skin reactions.23

ALK inhibitorsOne of the ALK inhibitors is crizotinib, a small molecule that selectively inhibits the TK receptor ALK and its oncogenic variants. It also inhibits the TK activity of the hepatocyte growth factor receptor (HGFR). Crizotinib is associated with hepatotoxicity, visual disturbances and severe cases of pneumonitis.3 It is also important for the radiologist to be aware of the association between crizotinib and the development of renal cysts, which should not be confused with metastases or other renal neoplastic processes.24

BRAF inhibitorsVemurafenib and dabrafenib are BRAF inhibitors (BRAFi) that selectively bind to mutated BRAF V600E proteins, but paradoxically also activate the MAPK signalling pathway, which is suspected of accelerating the development of secondary malignancies by activating RAS mutations. BRAFi have been associated with the development of secondary cancers, with this being the most serious adverse effect.25

These drugs tend to be mainly used in metastatic melanoma. The MEK inhibitor trametinib, in combination with BRAFi, has been reported to improve progression-free and overall survival in patients with metastatic melanoma.26

Anti-HERThe mAb trastuzumab selectively binds to the extracellular domain of EGFR-2 and HER-2. Its best known AE is cardiotoxicity, which is reversible and not associated with structural damage, unlike the cardiac toxicity of anthracyclines. Other complications include pneumonitis, infusion reactions and neutropenia.3

Other anti-HER agents are the TKI lapatinib and the mAb pertuzumab. They are associated with diarrhoea, alopecia and neutropenia.3

Proteasome inhibitorBortezomib is mainly used in the treatment of multiple myeloma and is associated with gastrointestinal disorders, asthenia, thrombocytopenia and peripheral neuropathy.27

Anti-CD20The mAb rituximab targets the CD20 antigen. It is used in the treatment of CD20+ B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. The most common complication is infusion reaction.28 As the number of B lymphocytes decreases, there is an increased risk of infections. Cases of asthenia, lung toxicity and intestinal perforation have also been described.3,29

Immune checkpoint inhibitorsICI are mAb that activate the adaptive immune response by modulating the function of T lymphocytes. These mAb are directed against molecular targets on the surface of the T cells to regulate their activation. In other words, they block different immune checkpoints to increase T lymphocyte-mediated tumour-cell destruction.30

Since 2011, seven ICI have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of different types of cancer. The first to be approved was ipilimumab, whose target is cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4 or cytotoxic lymphocyte-associated antigen 4). Nivolumab, pembrolizumab and cemiplimab target programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1). Atezolizumab, avelumab and durvalumab target programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1).3

The CTLA-4 antigen on the surface of the cytotoxic T lymphocyte acts as a negative regulator of its activation. Ipilimumab blocks the inhibitory signal of CTLA-4, and thus stimulates the proliferation and activation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes.30 The PD-1 protein belongs to the family of immune checkpoint proteins whose function is to modulate the T lymphocyte response and avoid an excessive autoimmune response. It also inhibits the action of T lymphocytes against tumour cells when it binds to the PD-L1 on the surface of the tumour cells; inhibiting the binding between PD-1 and PD-L1 thus facilitates the anti-tumour cell action of the T lymphocytes.30

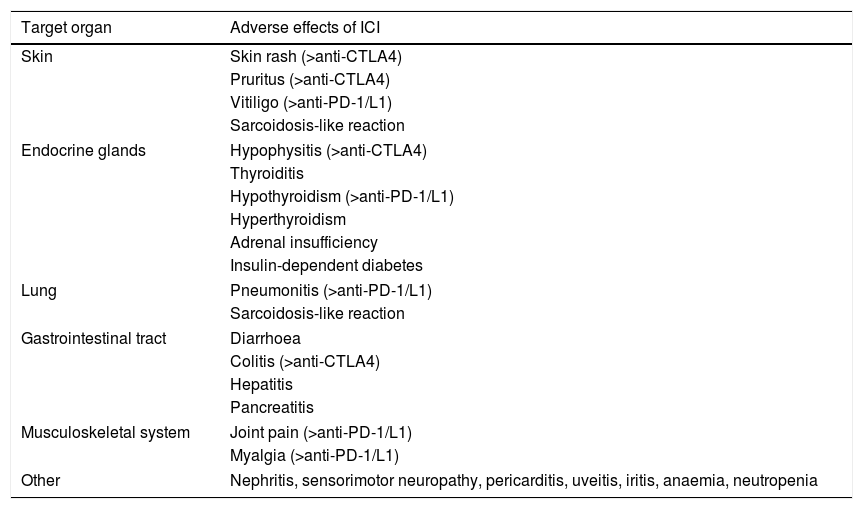

Immune-mediated toxicity occurs as a result of the induction of autoimmunity or a pro-inflammatory state (Table 2). It can occur early, even after the first treatment, or months later.31

Summary of the main adverse effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI). For some of the adverse effects, the type of ICI most likely to cause them is also shown.

| Target organ | Adverse effects of ICI |

|---|---|

| Skin | Skin rash (>anti-CTLA4) |

| Pruritus (>anti-CTLA4) | |

| Vitiligo (>anti-PD-1/L1) | |

| Sarcoidosis-like reaction | |

| Endocrine glands | Hypophysitis (>anti-CTLA4) |

| Thyroiditis | |

| Hypothyroidism (>anti-PD-1/L1) | |

| Hyperthyroidism | |

| Adrenal insufficiency | |

| Insulin-dependent diabetes | |

| Lung | Pneumonitis (>anti-PD-1/L1) |

| Sarcoidosis-like reaction | |

| Gastrointestinal tract | Diarrhoea |

| Colitis (>anti-CTLA4) | |

| Hepatitis | |

| Pancreatitis | |

| Musculoskeletal system | Joint pain (>anti-PD-1/L1) |

| Myalgia (>anti-PD-1/L1) | |

| Other | Nephritis, sensorimotor neuropathy, pericarditis, uveitis, iritis, anaemia, neutropenia |

Although the immune-mediated toxicity caused by the anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 drugs is similar, their incidence varies. A meta-analysis of 73 clinical trials on these AE found that toxicity was generally higher with anti-CTLA-4, lower with anti-PD-1 and slightly lower still with anti-PD-L1.32 The rate of AE seems to be higher with anti-CTLA-4 because it modulates the overall activity of “naive” and memory T cells in lymphatic tissues, while anti-PD-1/PD-L1 modulate local activity of T cells in peripheral tissues.33 The incidence of immune-mediated toxicity has also been found to be greater in combination therapy (anti-CTLA-4+anti-PD-1).32

Skin rash,pruritus, hypophysitis and colitis are therefore more common with the CTLA-4 inhibitor. Meanwhile, pneumonitis, hypothyroidism, myalgia, joint pain and vitiligo are more common with the PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.34

The AE do not only vary between CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, but also between different types of cancer. It is important to bear in mind that different types of cancer may produce different AE when treated with the same ICI.35 In addition, the complications associated with ipilimumab are dose-dependent, while those associated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 are dose-independent.35,36

Adverse effects:

- •

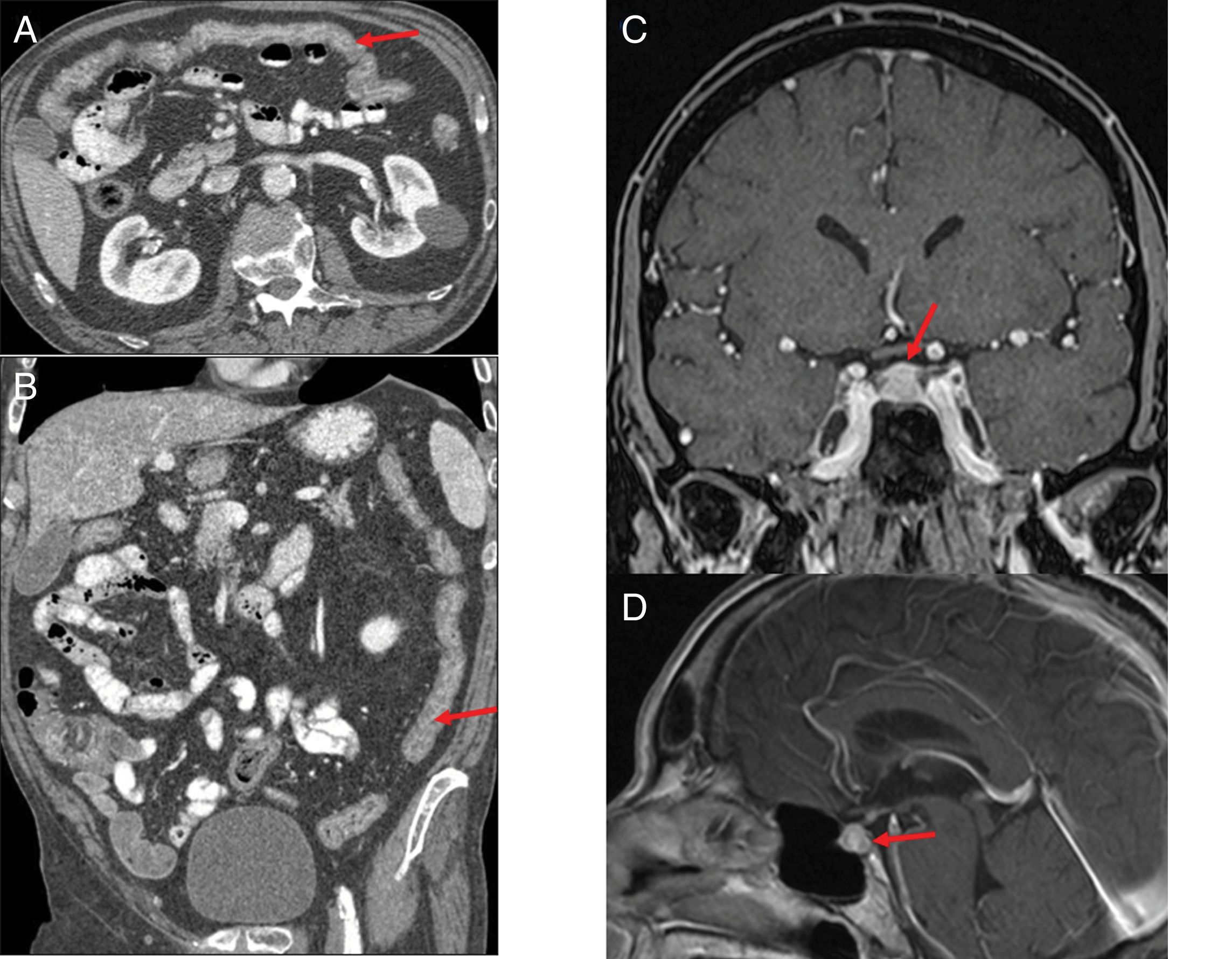

Diarrhoea and colitis: after dermatological toxicity, gastrointestinal AE are the most common, especially diarrhoea and colitis, and typically occur five weeks after starting treatment.31 Diarrhoea has a prevalence of 36–38% with ipilimumab and 8–20% with nivolumab and pembrolizumab.31 The prevalence of colitis is 8–10% with ipilimumab and 7–9% with nivolumab and pembrolizumab.31 Three patterns of colitis associated with immunotherapy are described: diffuse colitis, segmental colitis associated with diverticulitis and rectosigmoid colitis without diverticular disease.36 The typical findings in the case of the diffuse pattern are bowel wall thickening in the entire colon, hyper-enhancement of the mucosa and engorgement of mesenteric vessels (Fig. 8A and B). The second pattern typically shows bowel wall thickening, pericolic fat stranding, engorgement of mesenteric vessels, hyper-enhancement of the mucosa and diverticula. The third pattern is usually seen as wall thickening with engorgement of mesenteric vessels and pericolic fat stranding.36 Serious and life-threatening episodes occur as a result of bloody diarrhoea and intestinal perforation.

Figure 8.(A and B) Patient with stage IV squamous cell carcinoma of the lung, on third-line treatment with nivolumab, presenting with diarrhoea and a febrile episode. Computed tomography (CT) shows a slight diffuse wall thickening with increased enhancement of the mucosa of the colon (arrows), which extends from the transverse colon to the rectum, suggestive of colitis. (C and D) Patient with stage IV renal carcinoma due to pulmonary involvement, being treated in a clinical trial with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab therapy. The patient had a history of very intense headache for several days, without pyrexia and with normal brain CT. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) volumetric interpolated breath-hold examination (VIBE) (C) and T1 sequences with contrast (D) show the pituitary gland to be enlarged in relation to the age of the patient (craniocaudal diameter 9mm), with a convex-shaped superior margin and homogeneous enhancement which, in the clinical context of the patient is suggestive of immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced hypophysitis.

- •

Hepatitis: in imaging studies, hepatitis can manifest as hepatomegaly, periportal oedema or periportal lymphadenopathy.36 These findings are non-specific, so a diagnosis of exclusion should be made after having ruled out other possible causes.

- •

Pancreatitis: ICI-related pancreatitis is rare, with an incidence of less than 1%.36 It tends to be associated with elevated amylase and lipase levels and can be clinically asymptomatic.31 CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) show pancreatic parenchyma with decreased attenuation and increased size, with stranding of adjacent fat.36

- •

Hypophysitis: hypophysitis has primarily been associated with treatment with ipilimumab. It tends to occur nine weeks after starting treatment and has an incidence of 2–4%.31 Initial symptoms are headache and fatigue, followed by hypothyroidism, hypogonadism and hypocortisolism.30

- •

Araujo et al.37 reviewed the cases of 57 patients with ipilimumab-related hypophysitis and identified abnormal imaging findings in 77%. Typical imaging findings are a symmetrical increase in the size of the pituitary gland, which acquires a convex shape, with thickening of the stalk or infundibulum, and homogeneous enhancement after the administration of contrast (Fig. 8C and D). After corticosteroid treatment, follow-up images may show a decrease in pituitary size, a change in shape from convex to concave, and even in extreme cases an empty sella turcica. The majority of patients have no recovery of pituitary function.37,38

- •

Other endocrine AE: thyroiditis, hypothyroidism and adrenal insufficiency.36,38

- •

Pneumonitis: this is a serious AE because of its potential to be life-threatening. Cases can range from asymptomatic to causing respiratory failure and requiring admission to hospital.31

- •

ICI-associated pneumonitis is more common with anti-PD-1 and combined treatment with anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4.35 The incidence is reported to be higher the higher the dose of anti-PD-1 administered,34 and the incidence also seems to be higher in non-small cell lung cancer and patients with previous thoracic radiotherapy.36

- •

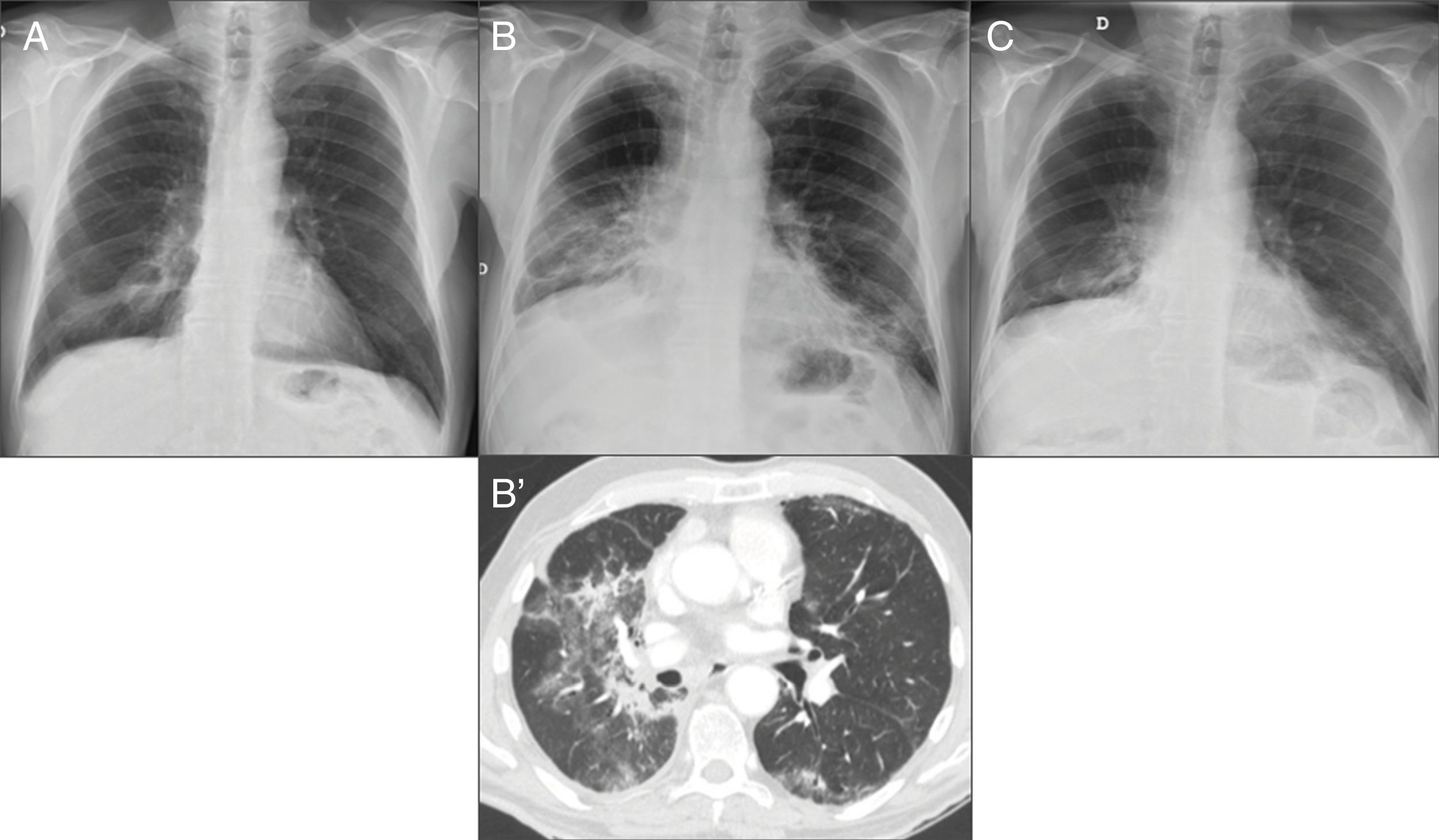

Four main patterns of CT findings have been described in immunotherapy-associated pneumonitis, following the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society classification of interstitial pneumonia: cryptogenic organising pneumonia (COP), non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), hypersensitivity pneumonitis and acute interstitial pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).39 The lower lobes are usually the most affected. Ground glass opacity is seen in virtually all cases, and a reticular pattern and consolidation in many40 (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.66-year-old man treated with nivolumab. (A) Chest X-ray pre-treatment with immunotherapy shows radiotherapy-related changes in the right lower lobe (RLL). (B) After 10 months of treatment, chest X-ray shows increases in density in both lower lung fields not seen on the previous X-ray. Computed tomography (B′) identifies ground glass areas associated with lung consolidation in the middle lobe, RLL and left lower lobe, compatible with nivolumab-induced pneumonitis. Corticosteroid treatment was given. (C) Chest X-ray performed one month later, in which radiological improvement can be seen.

- •

Sarcoidosis-like reaction: this type of reaction can involve lymphadenopathy, in which case mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy may be seen, or involve the lungs, where nodules with a mainly perilymphatic distribution pattern can be identified39 (Fig. 10). It is very important to take sarcoidosis-like reaction into account when conducting a follow-up study on a cancer patient which includes chest CT, as this AE should not be confused with metastatic progression.

Figure 10.A 54-year-old male with advanced renal cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab and ipilimumab combined therapy, whose images show a sarcoidosis-like pattern. (A) Chest computed tomography (CT) with mediastinal window shows mediastinal lymphadenopathy (an enlarged subcarinal node indicated with arrow). (B and C) The CT scan shows nodular images of a perilymphatic distribution pattern (arrows in the sagittal reconstruction) and pleural-based peripheral consolidation (arrows in the axial reconstruction). (D) Axial CT scan in the same patient after 2 weeks of corticosteroid treatment which shows radiological improvement.

In addition to the above AE, we should bear in mind that any pre-existing autoimmune disorder can get worse with immunotherapy (or become apparent if it was subclinical), and the radiologist is often the first to see it.

It is also important that when we have a patient on treatment with ICI, we locate their baseline imaging tests, i.e. the study from before they started treatment (usually a CT scan), and also consider it as baseline for AE; this will then allow us to detect radiological manifestations of immune-mediated toxicity early, sometimes before they manifest clinically, by interpreting changes in subsequent images.

The general management of immune-mediated toxicity, depending on the severity of the toxicity, includes: delaying the next planned immunotherapy dose; administration of corticosteroids; administration of immunosuppressive therapy with infliximab for toxicity resistant to corticosteroid therapy; and discontinuation of the treatment responsible.31,38

ConclusionUnderstanding the molecular mechanism of TT and recognising their AE is essential for effective treatment and to prevent possible misdiagnoses. Close communication between the radiologist and the oncologist is essential.

Key points- •

Greater understanding of tumour biology has led to new anticancer drugs, known as “targeted therapies” (TT), which target specific signalling pathways necessary for the cancer's development. These therapies come accompanied by new adverse effects (AE), which radiologists need to be aware of.

- •

TT can be classified into groups according to their mechanism of action, and each group has its own specific set of AE.

- •

The AE radiologists may come across most often are colitis, pneumatosis, intestinal perforation, haemorrhages, pancreatitis, pneumonitis, etc.

- •

ICI are the newest drugs to be added to TT and immunotherapy in particular. Their most relevant AE from a radiology point of view are colitis, hepatitis, pancreatitis, hypophysitis, thyroiditis, pneumonitis and sarcoidosis-like syndrome.

1. Responsible for the integrity of the study: PLS, NAA and GUG.

2. Study conception: PLS, NAA and GUG.

3. Study design: PLS, NAA and GUG.

4. Data acquisition: PLS, NAA and GUG.

5. Data analysis and interpretation: PLS, NAA and GUG.

6. Statistical processing: N/A.

7. Literature search: PLS, NAA and GUG.

8. Drafting of the article: PLS, NAA and GUG.

9. Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: PLS, NAA and GUG.

10. Approval of the final version: PLS, NAA and GUG.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: López Sala P, Alberdi Aldasoro N, Unzué García-Falces G. Efectos adversos de las terapias dirigidas contra el cáncer: lo que el radiólogo debe saber. Radiología. 2020;62:229–242.