To investigate whether increasing temporal resolution with higher parallel imaging (PI) reduction factors (RF) in both breath-hold and free breathing approaches, using a non-contrast T1-weighted 3D gradient echo (GRE) sequence and a 32-channel phased array coil, permits diagnostic image quality, with potential application in patients unable to cooperate with breath-hold requirements.

Materials and methodsThe 9 healthy subjects (5 females and 4 males; age range was 20–49, mean 36 yrs) were recruited. A 3D GRE MR imaging of the abdomen was performed on 1.5T MR system using a 32-element phased-array torso coil with PI RFs of 2, 4 and 6, breath hold and free breathing. Two reviewers retrospectively qualitatively evaluated all sequences for image quality, extent of artifacts, including motion, truncation, aliasing, pixel graininess and signal heterogeneity. The results were compared using Wilcoxon signed rank and a Bonferroni adjustment was applied for multiple comparisons.

ResultsImage quality and extent of artifacts were better with breath hold than with free breathing acquisitions. The rate of artifacts increased with higher RF. The best quality was acquired with breath hold sequence using RF=2. RF=4 had lower but diagnostic rates (p=0.004). The severity of artifacts, mainly pixel graininess (p=0.004), rendered sequences with RF=6 non-diagnostic. All sequences were non-diagnostic in free breathing acquisitions.

ConclusionBreath hold sequences with RF=2 had excellent quality and RF=4 had good quality and may be potentially used in partially cooperative patients. None of the sequences was considered diagnostic in free breathing acquisitions.

Analizar si el aumento de la resolución temporal utilizando mayores factores de reducción (FR) de imagen en paralelo (IP), tanto en apnea como con respiración libre, utilizando una secuencia 3D con eco de gradiente (EG) potenciada en T1, sin contraste y una bobina de múltiples elementos (phased array) de 32 canales, proporciona una calidad de imagen diagnóstica, con posibilidad de ser aplicada en pacientes que no puedan cooperar para mantener la apnea.

Material y métodosSe incluyeron en el estudio 9 sujetos sanos (5 mujeres y 4 varones; rango de edad: 20-49; media: 36 años). Se les realizó un estudio de RM abdominal con secuencias 3D EG en un equipo de 1,5T con bobina de múltiples elementos (phased-array) de 32 canales con FR de imagen en paralelo de 2, 4 y 6, en apnea y con respiración libre. Dos revisores evaluaron retrospectiva y cualitativamente la calidad de imagen de las secuencias, la magnitud de los artefactos, incluyendo los artefactos de movimiento por reducción de señales, de solapamiento (aliasing), de granulado de los píxeles y la heterogeneidad de la señal. Los resultados se compararon mediante la prueba de Wilcoxon de los rangos con signo y la corrección de Bonferroni para comparaciones múltiples.

ResultadosLa adquisición en apnea proporcionó mejor calidad de imagen y menos artefactos que la adquisición con respiración libre. La tasa de artefactos fue mayor para FR más altos. La mejor calidad se obtuvo con secuencias en apnea con un FR=2. Un FR=4 presentó tasas menores pero diagnósticas (p=0,004). La severidad de los artefactos, en especial el granulado de los píxeles (p=0,004), hizo que las secuencias con un FR=6 no fueran diagnósticas. Ninguna de las secuencias obtenidas con respiración libre fue diagnóstica.

ConclusiónLas secuencias obtenidas en apnea con un FR=2 presentaron una calidad de imagen excelente, y aquellas con un FR=4 presentaron una calidad buena y potencialmente se pueden aplicar en pacientes poco colaboradores. Ninguna de las secuencias obtenidas con respiración libre se consideró diagnóstica.

Despite recent technical developments like parallel imaging (PI), the shortest available acquisition times are generally still too long for high diagnostic quality dynamic abdominal magnetic resonance (MR) imaging in non cooperative patients such as agitated, sedated or unconscious patients,1–4 or in partially cooperative patients who can only suspend their breath for a few seconds.

Three-dimensional (3D) gradient echo (GRE) imaging with uniform fat saturation is the primary pulse sequence used for multiphase post gadolinium imaging of the upper abdomen, which is the mainstay for high quality diagnostic studies and is arguably the single most important dataset in a typical abdominal MR exam.4 The inability of non-cooperative patients to hold their breath impairs the image quality substantially on T1-weighted GRE sequences.5–8 It is the authors’ experience that with 1.5T systems and with a 8-channel phased array coil, the use of reduction factor (RF) greater than 2 in T1-weighted 3D GRE dynamic imaging is associated with significant degradation of image quality, which is consistent with previous reports.2,9 The recent development of multi channel receive coils would also provide a solution to the limitations of breath holding requirements. New 32 element phased array coils, produce higher signal to noise ratio (SNR), and may allow higher PI RFs,10–14 permitting extremely short acquisition times, potentially with diagnostic quality T1-weighted dynamic imaging in non-cooperative and partially cooperative patients.3,12 Previous reports using commercially available systems have not tested temporal resolution for parallel imaging higher than RF=2 for abdominal T1-weighted 3D-GRE dynamic imaging, including in non-cooperative patients.2,9

The purpose of the present study is to investigate whether increasing temporal resolution with higher RFs, in both breath-hold and free breathing approaches, using a non-contrast T1-weighted 3D GRE sequence and a 32-channel phased array coil, permits diagnostic image quality, with potential application in patients unable to cooperate with breath-hold requirements. Such information can be used to determine the optimal 3D GRE sequence and RF combination for a given level of patient cooperation.

Materials and methodsSubject selectionA total of 9 healthy subjects (5 female, 4 male) were recruited for this prospective study. The age range was 20–49yrs (mean 36yrs).

This HIPPA compliant study was approved by our institutional IRB, and signed informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Magnetic resonance imaging techniqueAll MR examinations were performed on a 1.5-T (Avanto, Siemens Medical Systems, Malvern, PA) MR system using a 32-element phased-array torso coil with k-space based PI (GRAPPA−generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions) reconstruction, RFs of 2, 4 and 6, breath hold and free breathing. The used coil is a 32-channel phased-array coil with an anterior and a posterior part. Each part is 30cm×40cm and contains 16 coil elements. The 32 elements of the coil are arranged as 4 H-F×4 R-L×2 A-P.

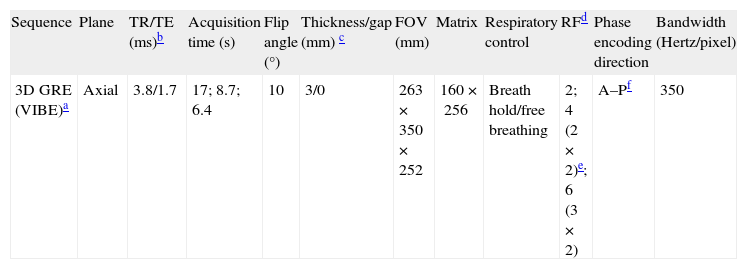

All subjects underwent a transverse T1-weighted fat-suppressed three-dimensional GRE (VIBE- volume interpolated breath hold examination) MR imaging of the abdomen. Information on the used parameters can be found in Table 1.

Detailed parameters of 3D gradient-echo (GRE) sequences.

| Sequence | Plane | TR/TE (ms)b | Acquisition time (s) | Flip angle (°) | Thickness/gap (mm) c | FOV (mm) | Matrix | Respiratory control | RFd | Phase encoding direction | Bandwidth (Hertz/pixel) |

| 3D GRE (VIBE)a | Axial | 3.8/1.7 | 17; 8.7; 6.4 | 10 | 3/0 | 263×350×252 | 160×256 | Breath hold/free breathing | 2; 4 (2×2)e; 6 (3×2) | A–Pf | 350 |

The used echo time of 1.7ms with the bandwidth of 350Hz/px requires a very slight/weak asymmetry. However, the asymmetry was the same for all accelerations. Although it does impact the image quality, it is a fixed variable in this study. Subjects were instructed to breath normally during free breathing acquisition. No respiratory trigger or navigation techniques were used. The acquisition times were 17s for RF=2, 8.7s for RF=4 and 6.4s with RF=6.

Magnetic resonance imaging interpretationQualitative analyses3D GRE sequences of all patients were independently, retrospectively and blindly evaluated on a workstation by 2 different reviewers with 2 and 18 years post-fellowship training experience to determine image quality and extent of artifacts. The reviewers were blinded to the parameters of the sequences that they reviewed. A training set was performed with one patient. This data was included in the study.

Image quality was analyzed using a five-point scale (1, very low quality; 2, low quality; 3, fair quality; 4, good quality; 5, excellent quality), which evaluates overall image quality with higher scores representing better overall image quality. Sequences in which the image quality was between 3 and 5 were considered to be diagnostic quality.

The reviewers qualitatively analyzed each image for motion, truncation, aliasing and pixel graininess artifacts and for signal heterogeneity. Extent of artifacts was analyzed using a six-point scale (1, profound; 2, severe; 3, moderate; 4, mild; 5, minimal; 6, imperceptible) with higher scores representing fewer artifacts. Sequences in which the extent of artifacts was between 4 and 6 were considered to be diagnostic quality.

Motion artifact was defined as blurring or ghosting of the image in the phase encoding direction.15 The time difference in the acquisition of adjacent points in the phase encoding direction is much longer, when compared with the frequency encoding direction and is equal to the repetition time used for the sequence. The positional difference because of motion introduces phase differences between the views in k-space that appear as ghost or blurring artifacts on the image.15

Truncation or Gibbs artifacts were defined as bright or dark lines that appear parallel with and adjacent to the borders of an area of abrupt signal intensity change on MR images.15 Insufficient collection of samples in either the phase encoding direction or the readout direction leads to Gibbs rings as a result of the Fourier transform.15

Aliasing artifact was described as a wraparound image. Aliasing can occur whenever any part of the body extends outside the field of view and a signal produced by this structure reaches the receiver coil. Parallel reconstruction techniques can reduce the fold-over component resulting from the reduced sampling of k-space lines, but if the calculated missing lines are not sufficient, some aliasing persists. When this occurs, uncorrected aliasing artifacts may arise from structures separated by the aliasing distance in the phase-encoding direction, often placing wraparound artifact at or near the center of the image.15,16

Pixel graininess was determined as the presence and extent of granularity and reflects the overall magnitude and inhomogeneity of background noise.15

Signal heterogeneity was considered present when lack of uniformity of signal intensity was present within a slice, occurring most often in the phase-encoding direction.

The authors did not perform quantitative analyses, including the use of phantom studies, for the purpose of this preliminary study is accomplished with a qualitative analysis.

Statistical analysisWilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the three breath hold and free breathing sequences for the parameters of qualitative analyses, with α=0.05. The Bonferroni adjustment was applied for multiple comparisons. These analyses were performed using the web calculators of VassarStats (http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/VassarStats.html) and SISA (http://www.quantitativeskills.com/sisa/). Inter observer reproducibility for the qualitative data was assessed using Kappa statistics, performed with ComKappa (http://www2.gsu.edu/∼psyrab/BakemanPrograms.html).

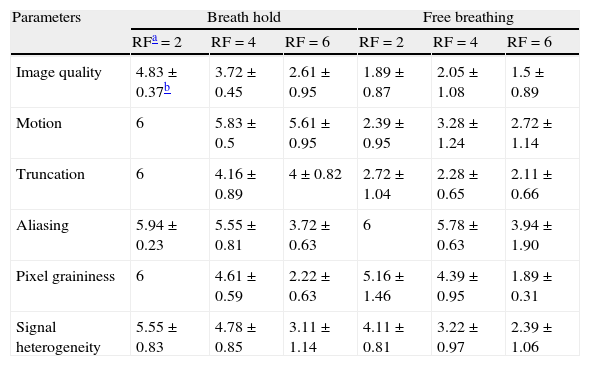

ResultsThe results of independent qualitative analyses for each sequence are displayed in Table 2. All results are reported as mean±standard deviation.

Results of the qualitative analyses.

| Parameters | Breath hold | Free breathing | ||||

| RFa=2 | RF=4 | RF=6 | RF=2 | RF=4 | RF=6 | |

| Image quality | 4.83±0.37b | 3.72±0.45 | 2.61±0.95 | 1.89±0.87 | 2.05±1.08 | 1.5±0.89 |

| Motion | 6 | 5.83±0.5 | 5.61±0.95 | 2.39±0.95 | 3.28±1.24 | 2.72±1.14 |

| Truncation | 6 | 4.16±0.89 | 4±0.82 | 2.72±1.04 | 2.28±0.65 | 2.11±0.66 |

| Aliasing | 5.94±0.23 | 5.55±0.81 | 3.72±0.63 | 6 | 5.78±0.63 | 3.94±1.90 |

| Pixel graininess | 6 | 4.61±0.59 | 2.22±0.63 | 5.16±1.46 | 4.39±0.95 | 1.89±0.31 |

| Signal heterogeneity | 5.55±0.83 | 4.78±0.85 | 3.11±1.14 | 4.11±0.81 | 3.22±0.97 | 2.39±1.06 |

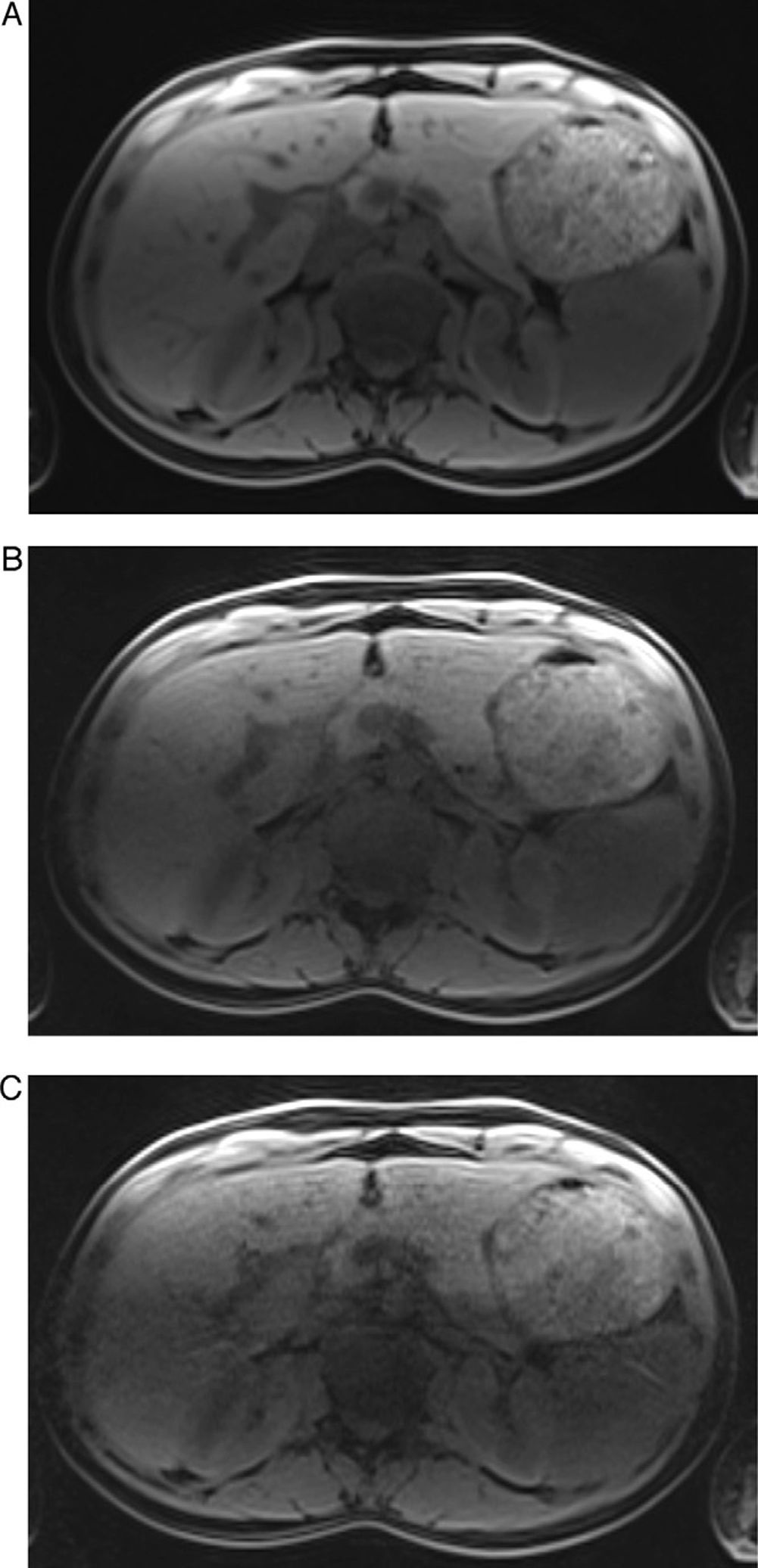

RF=2 and RF=4 breath hold acquisitions had an average diagnostic image quality, although with significantly better ratings using RF=2 (p=0.004), mainly because of higher ratings of pixel graininess (p=0.006) artifacts. RF=6 had an overall non-diagnostic image quality (Fig. 1), significantly differing from RF=4 (p=0.01) and RF=2 (p=0.004). Pixel graininess was the main cause for this non-diagnostic image quality of RF=6, comparing with RF=4 (p=0.004) and RF=2 (p=0.004). RF=6 also had a lower but almost diagnostic rate of aliasing artifacts (3.7±0.6).

Breath hold T1 weighted 3D GRE images with RF=2 (A), RF=4 (B) and RF=6 (C) of the same subject. Notice the worsening image quality with increasing RF. The image quality of (A) was considered excellent with almost no artifacts. Notice the clear definition of the liver, pancreas and spleen edges and of the portal vein branches contours. In (B) and (C) there is progressive worsening of artifacts, mainly pixel graininess and central aliasing in the center of the image. Although there is only slight blurring of the liver structures in RF=4 (B), artifacts present in image (C) cause substantial blurring and lower definition of the liver, rendering (C) non-diagnostic.

Concerning signal heterogeneity, RF=6 also had lower and significantly different ratings comparing with RF=2, both in breath hold (p=0.004) and free breathing (p=0.01) acquisitions.

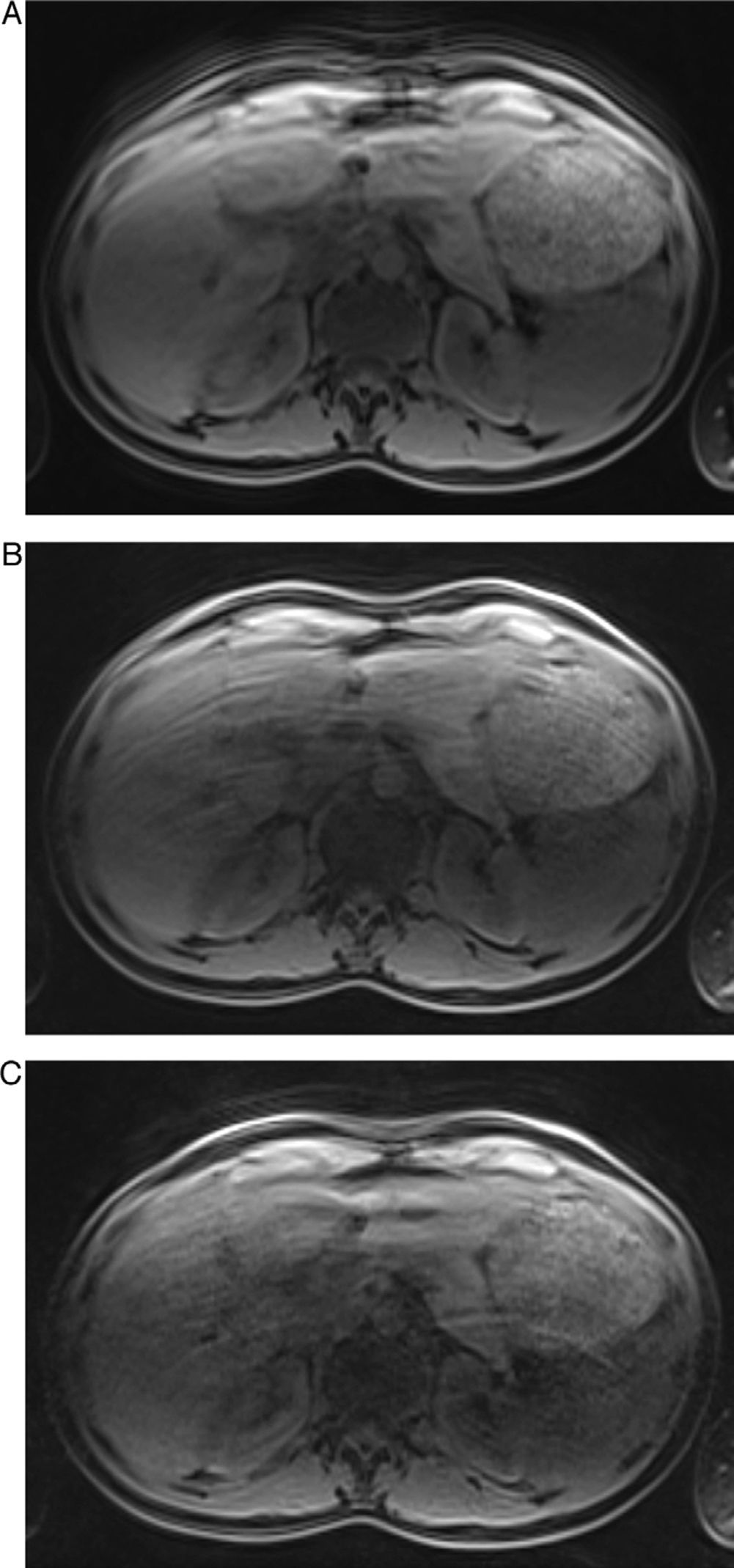

All free breathing acquisitions were rated non-diagnostic (Table 2). The main cause for the non-diagnostic rating of RF=2 and RF=4 free breathing acquisitions were motion artifacts (Fig. 2).

Free breathing T1 weighted 3D GRE images with RF=2 (A), RF=4 (B) and RF=6 (C) of the same subject. All images were considered non-diagnostic. Notice the presence of motion artifacts with all RFs. In (C) pixel graininess and aliasing artifacts are also clearly evident in the center of the image contributing furthermore for image degradation.

The agreements between the two reviewers for the independent qualitative data analyses were good to excellent with Kappa>0.8.

DiscussionThe results of our study revealed that breath hold RF=2 and RF=4 sequences had a significantly better overall image quality compared to their corresponding free breathing acquisitions. Therefore RF=4 probably should be used in partially cooperative patients, because of its short acquisition time (around 9s). In other words, if a patient can hold his breath for 9s, but not for 17s then it is likely that better overall image quality will be obtained using RF=4 in a breath-hold approach (image quality 3.7±0.4) than using RF=2 in a free-breathing approach (image quality 1.9±0.9), which is consistent with other reports using lower RF and non-accelerated 3D GRE.9

Breath hold RF=6 had the lowest average rates amongst the breath hold sequences, and overall image quality was considered non diagnostic, although almost in the diagnostic range. Pixel graininess was the main parameter responsible for the non-diagnostic quality of RF=6, with significant differences comparing to RF=2 and RF=4 (p=0.004). Pixel graininess reflects low SNR. As the reduction factor increases, the noise amplification associated with g-factor and reduced noise-averaging results in an increasingly fast lowering of SNR.17–20 The g-factor measures the spatially varying level of noise amplification occurring as a result of the reconstruction process. It depends not only on the number and configuration of the coils, but also with the used reduction factor.17–21 The use of a coil like the one in our study, which clearly outnumbers the acceleration factor, should expect for a better rate concerning PI artifacts (including pixel graininess) in high acceleration factors.9,19 It is possible that pixel graininess may be an intrinsic limitation of higher PI reduction factors in the conditions of our study. Previous reports suggested that in field strengths up to 5T, assuming that an optimal coil is used, for RFs above a certain critical limit (3–4 for undersampling along one dimension), g-factor increases exponentially.22–25 Applications that maximize baseline SNR, such as high and ultra-high field strengths may be useful in the setting of parallel imaging.18,19,24–26 In addition, it is possible that reduced noise amplification may be overcome not only with further coil developments,17,19,27 but also k-space sampling pattern improvements.28–30

Signal heterogeneity, aliasing and truncation all had increasing lower rates with higher RF, although they were not found to be major causes of non diagnostic quality of RF=6. Signal heterogeneity is most likely a direct result of the fact that the g factor becomes more spatially heterogeneous with increasing reduction factor. Aliasing and truncation are probably related with smaller numbers of phase encoding steps at high RF5,15 and may be potentially improved, with further sequence optimization.

Our intention in performing free breathing acquisitions was to determine if image quality was superior with the short duration high RFs. Our clinical experience with currently available partial sampling and motion compensation techniques indicates that they are unreliable and often when they fail they are prone to severe motion artifacts. We had hoped that the very short acquisition times here would obviate the need for such techniques. All free breathing acquisitions were motion sensitive and rated non-diagnostic regardless of the reduction factor and therefore the acquisition duration. Our explanation for this, and for the poor performance of the short duration RF=6 sequence alone during breathing, is that despite the short duration of the sequence (approximately 6s), central k-space duration was unaffected by increasing RFs, and this sampling was not sufficiently short to freeze motion. Since k-space center determines overall image quality,6,7,28,31 the preservation of a still relatively long k-space for all sequences resulted in poor image quality for all free-breathing sequences, regardless of their duration. We do not however consider that attempt to render sequences resistant to artifacts should be abandoned, rather alternative additional strategies should be examined such as different methods of k-space encoding patterns that could potentially have a higher SNR per unit time.28–30,32

Respiratory triggering and navigation are routinely used in abdominal studies for T2-weighted imaging in intent to limit respiratory motion artifacts.33–35 These techniques are most effective and useful for long TR imaging (typically T2-weighted imaging) where the normal variations in the respiratory cycle will not significantly affect the signal. Less attention has been paid to their use in mitigating respiratory motion artifacts in T1-weighted imaging.33,36,37 Triggering and navigation techniques in common use tend to greatly disturb the steady state magnetization characteristically achieved with T1-weighted imaging, which can explain their ineffectiveness with volumetric 2D- and 3D-spoiled GRE T1-weighted imaging. Furthermore, these techniques can fail in cases of irregular respiration, they require additional steps in the clinical workflow, and their longer-duration do not allow dynamic post-contrast imaging, critical for abdominal imaging.38–40

Our study had some limitations. We only used healthy volunteers. A future potential study, now that our preliminary results show the feasibility of RF=4 in breath hold acquisitions, would be to compare results of image quality and artifacts between partially cooperative patients (using breath hold RF=4) and cooperative patients (using breath hold RF=2). In addition, because of constraints related with using healthy subjects, we did not perform a post-contrast evaluation, which would have higher SNR than non-contrast images, potentially out weighing loss in SNR caused by parallel MRI. Another limitation was that we only performed a qualitative evaluation, which provides useful information regarding the purpose of our study: to determine the optimal 3D GRE sequence and RF combination for a given level of patient cooperation. Quantitative measurements may provide useful data in order to further optimize and compare sequences. Another limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size, with its corresponding implications in statistical power. It is conceivable that future studies may show significant differences that were not found in this study for the same tested parameters, although our rating results suggest that they probably are not the major cause of non-diagnostic image quality of higher RF sequences. Finally a major limitation of all studies that evaluate new technology is that the deficiencies revealed might more reflect the level of optimization of techniques rather than a fundamental problem with them.

In conclusion, our study indicates that in partially cooperative patients (who cannot hold their breath for 17s) it is likely that better overall image quality will be obtained using RF=4 in a breath-hold approach than using RF=2 in a free-breathing approach. It also indicates that RF=6 non diagnostic rates mainly reflect low SNR, despite the use of a 32-channel phased array coil, which may be an intrinsic limitation of the higher PI reduction factors employed with the tested 3D GRE sequence and used phased array coil at 1.5T. There were no consistent advantages using high RF in free breathing approach.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for the study's integrity: RCS.

- 2.

Conception of the study: VH, BD, RODC, MR, LBB, CS, MDT and RCS.

- 3.

Design of the study: RS, VH, BD, MR and RODC.

- 4.

Acquisition of data: RS and LBB.

- 5.

Analysis and interpretation of data: VH, BD, RODC, MR, LBB, CS, MDT and RCS.

- 6.

Statistical analysis: VH, BD and MR.

- 7.

References search: VH, BD, MR, RODC and RS.

- 8.

Writing of the manuscript: VH, MR, BD and RCS.

- 9.

Critical review with intellectually relevant contributions: VH, BD, RODC, MR, LBB, CS, MDT and RCS.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: VS, BD, RODC, MR, LBB, CS, MDT and RCS.

The authors declare not having any conflict of interest.

Please cite this article: Herédia V, et al. Comparación de una secuencia en 3D con eco de gradiente potenciada en T1 con 3 factores de reducción de imagen en paralelo diferentes, en apnea y respiración libre, utilizando una bobina de 32 canales a 1,5T. Estudio preliminar. Radiología. 2014;65:533–540.