Leishmaniasis is a parasitic zoonosis caused by protozoa from the genus Leishmania, which includes over 20 species and is transmitted by phlebotomine sand flies. Most cases of visceral leishmaniasis occur in the Indian subcontinent, East Africa, and Brazil. However, the disease is also endemic in the Mediterranean basin, where Leishmania infantum is the primary causative agent.1 Clinically, Leishmaniasis manifests as visceral, cutaneous, or mucosal forms. Visceral disease, the most severe form, is typically caused by Leishmania donovani or L. infantum.2 The mucosal form usually affects the upper respiratory tract and is classified as primary (without clinical features suggesting infection elsewhere) or secondary (associated with cutaneous or visceral disease).3 In this manuscript we describe three cases of immunocompetent patients with rare mucosal leishmaniasis affecting the trachea or bronchi, managed at our center from 2009 to 2023.

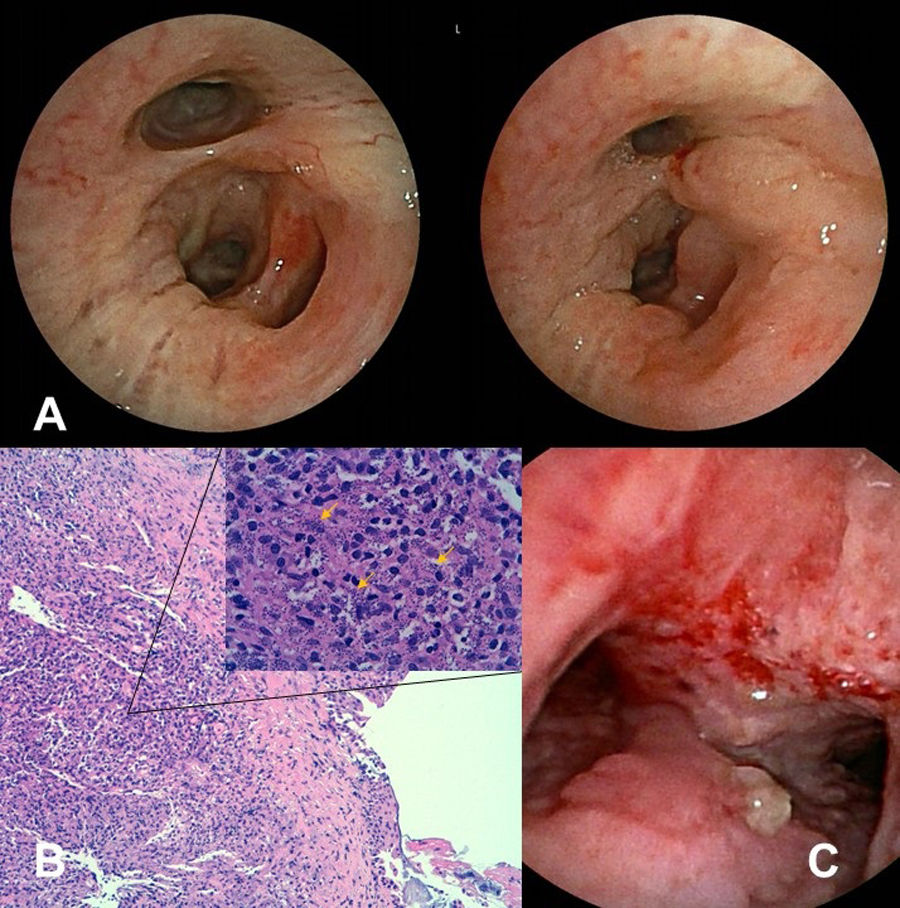

Patient 1 was a 68-year-old immunocompetent Spanish male with recurrent bronchospasm. He had been diagnosed with Leishmaniasis through Leishmania DNA detection by PCR in a laryngeal biopsy performed due to progressive dyspnea, dysphonia, dysphagia, and constitutional symptoms (fatigue, anorexia, weight loss). He had no cytopenias or other analytic abnormalities. He responded well to liposomal amphotericin B (40mg/kg total over one month) but had persistent dysphagia for solids. Four years later, he developed progressive exertional dyspnea, and bronchoscopy revealed rounded lesions in the mucous membrane from the subglottic space to the main carina, with extrinsic compression of both main bronchi. Biopsy with PCR confirmed tracheal Leishmaniasis. He received weekly liposomal amphotericin B (4mg/kg) for one month, followed by monthly maintenance for a year. Bronchoscopy two weeks after the first dose showed reduced inflammation, with subsequent biopsies negative for Leishmania (Fig. 1A). Over an eight-year follow-up, he experienced two clinical relapses (Fig. 1A), requiring further treatment with amphotericin B. He is currently on prophylactic monthly inhaled pentamidine.

The results of investigations in three patients with Leishmaniasis. (A) Images from patient 1. Macroscopic evaluation by bronchoscopy at 6 months after initial treatment (left image) and 24 months during a relapse (right image). (B) Images from patient 2. Leishmania amastigotes (yellow arrows) and inflammatory infiltrates in bronchial tissue (hematoxylin and eosin staining at ×100 and ×630). (C) Image from patient 3. Infiltration of the distal trachea and carina by Leishmania at bronchoscopy showing abundant edema and unstructured tissue with a predominance of granulomatous mucosa.

Patient 2 was a 39-year-old immunocompetent Moroccan male who had lived in Spain for six years. He was being investigated for chronic dyspnea, asthenia, and productive cough. Tuberculosis and other infections were excluded, leading to a presumptive sarcoidosis diagnosis based on computed tomography findings of multiple adenopathies and diffuse granulomatous inflammation in a tracheal biopsy. He started systemic corticosteroids. One year later, he was admitted with severe bronchospasm; sputum culture isolated Nocardia sp., treated with cotrimoxazole. Bronchoscopy revealed irregular, swollen mucosa with nodules causing bilateral superior bronchial stenosis which induced severe bronchial obstruction. Histology confirmed tracheal and bronchial Leishmaniasis (Fig. 1B), and he was treated with liposomal amphotericin B. He had multiple bronchospasm episodes requiring hospitalizations, progressing to refractory bronchospasm with non-invasive mechanical ventilation. He ultimately presented with massive hemoptysis, leading to cardiorespiratory arrest and death.

Patient 3 was an 80-year-old immunocompetent Spanish male with persistent laryngeal edema of unknown origin for over three years. He presented with acute respiratory insufficiency due to laryngeal inflammation, requiring an emergency tracheostomy. Decannulation was unsuccessful due to persistent inflammatory signs. Two years later, he developed inspiratory stridor and a granuloma at the distal cannula tip. Bronchoscopy showed edema and irregular, bumpy tracheal mucosa extending into the main bronchi (Fig. 1C). Laryngeal and tracheal biopsies identified intracellular microorganisms consistent with Leishmania species. He received five days of liposomal amphotericin B during hospitalization, followed by monthly doses. His treatment response remains under evaluation.

Leishmaniasis is endemic in the Mediterranean basin, though its prevalence is likely underestimated.4 Specifically in Spain, underreporting remains a challenge.5 While immunosuppression is a known risk factor for visceral leishmaniasis,1,6 mucosal leishmaniasis due to L. infantum is increasingly recognized in immunocompetent individuals.3 Pulmonary spread of Leishmania is rare and primarily described in immunocompromised patients, particularly those with HIV.7,8

This report highlights three immunocompetent patients diagnosed with tracheal or bronchial leishmaniasis, each with different clinical manifestations and outcomes. In all three cases, HIV infection was ruled out, and comprehensive evaluations excluded other causes of immunosuppression, such as haematological malignancies and the use of immunosuppressive therapies. However, two factors may contribute to mucosal disease development in these cases: all patients were receiving low-dose systemic corticosteroids at diagnosis, suggesting a degree of immunosuppression, and one patient was elderly, raising the question of immunosenescence as a risk factor.

Mucosal leishmaniasis typically presents with granular swelling or nodular/polypoid lesions confined to the upper respiratory tract (nose, mouth, pharynx, larynx).2,9 Such lesions had been described in patients from Sudan and other African regions,2 but cases in Europe have increased in the last 20 years.9 In the Mediterranean, the larynx and oral mucosa are the most commonly affected sites.10 Lower respiratory tract involvement remains rare, with limited data available. To our knowledge, only three other tracheal or endobronchial cases have been reported in Spain,11–13 and isolated cases in Greece,1 France,14 the UK,2 and Italy.15 Notably, all cases were likely acquired in the Mediterranean, except for the UK case, which involved a Sudanese patient.

Bronchoscopic findings have not been consistently described in reported cases, but our three patients exhibited irregular, bumpy mucosa, similar to descriptions by Pavon et al.12

Identifying the Leishmania species in these cases would have been valuable for epidemiological purposes, but initial low clinical suspicion led to a lack of culture performance, precluding species identification. This issue is common in reported cases. Diagnosis was based on Leishmania amastigotes observed in biopsy specimens. Liposomal amphotericin B was the primary treatment in all three cases, yielding variable responses.

This report underscores the diverse clinical presentations of leishmaniasis in endemic areas, emphasizing the need for early recognition to prevent diagnostic delays and disease progression. Bronchoscopy with biopsy should be considered in patients with unexplained bronchial symptoms, given the seroprevalence of Leishmania infection in our region.

Informed consentAll three patients gave their consent for the use of their clinical information in this case series.

Artificial intelligence involvementNo artificial intelligence tools were used in the creation or analysis of this article.

FundingThis research received institutional support from the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors have contributed significantly to the work: Carmen Lores and Domingo Madera were involved in manuscript writing, literature review, and the diagnostic process of the third case; Rosa López Lisbona participated in the performance of the endoscopic examinations; Núria Sabé participated in the therapeutic management of all three cases; Nuria Baixeras contributed to the pathological diagnosis; Rosana Blavia participated in the diagnosis of the first case; and Mariana Muñoz assisted in manuscript editing and review.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to the content of this article.