We present the case of a 63-year-old male with a history of bilateral lung transplantation due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, receiving immunosuppressive treatment initially with Basiliximab followed by tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisone, as well as prophylaxis with nebulized amphotericin B and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. The patient had a favorable post-transplant evolution.

At 10 months post-transplant, he experienced a decline in lung function, with a reduction in FEV1 from 3170ml to 2500ml (−19%) and a fall in FEV1/FVC ratio from 82% to 63%. The patient's best post-transplant spirometry showed an FVC of 3870ml and an FEV1 of 3170ml. A chest X-ray revealed consolidation in the right lower lobe (RLL), coinciding with cytomegalovirus (CMV) viremia of 27,630IU/ml. At that time, tacrolimus trough levels were 13ng/ml. During the previous months, immunosuppressant levels had remained stable, ranging between 10 and 16ng/ml. The target therapeutic range for tacrolimus was approximately 15ng/ml during the first six months post-transplant and around 10ng/ml up to the end of the first year. Suspecting CMV pneumonitis, valganciclovir was initiated. Despite this, the patient exhibited clinical (cough, purulent expectoration) and functional deterioration, leading to hospital admission for further diagnostic evaluation.

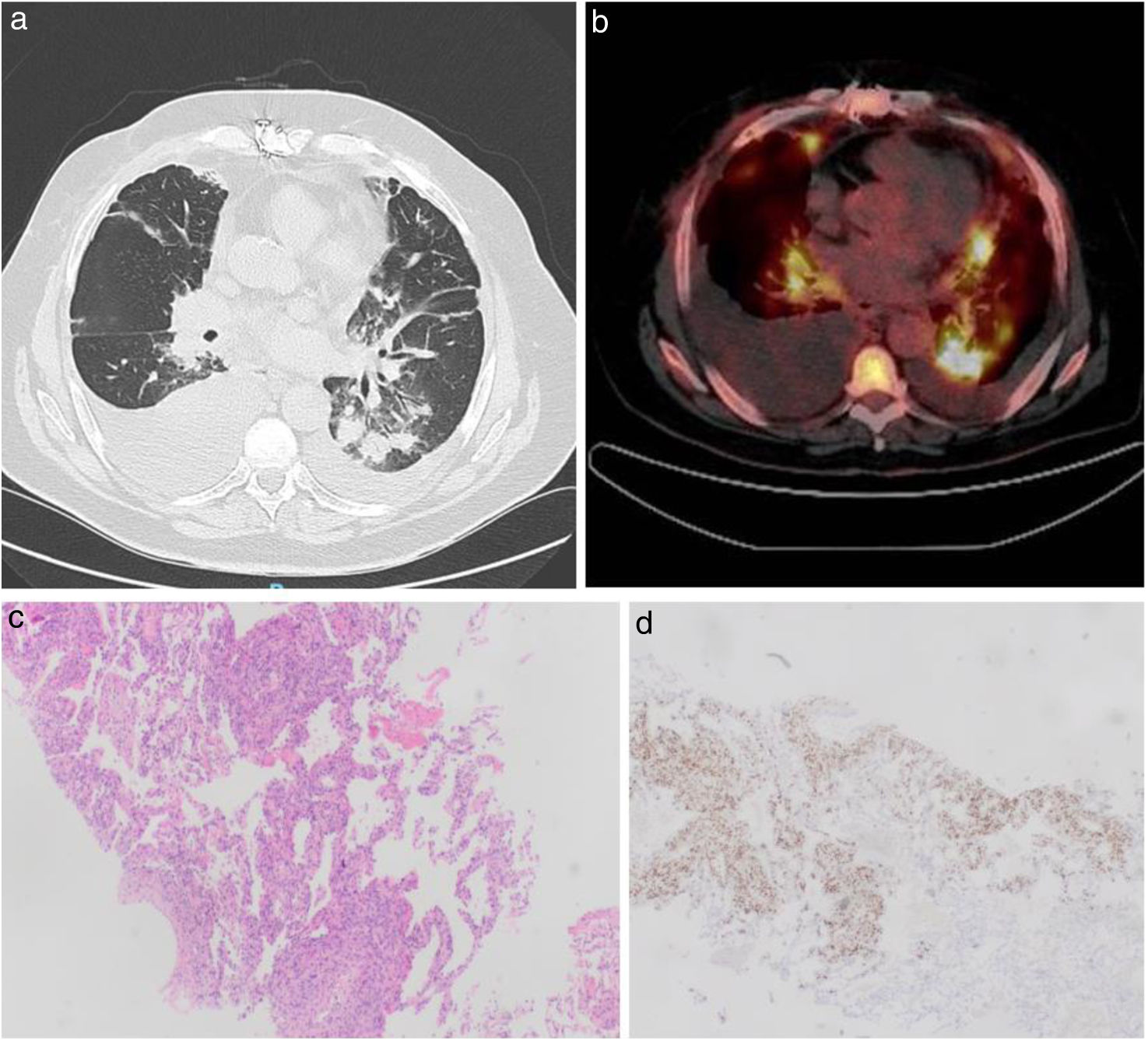

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest confirmed central peribronchovascular consolidation in the RLL, with numerous nodular images, some with air bronchograms and others with a surrounding ground-glass halo (Fig. 1a), along with bilateral pleural effusion. Bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and transbronchial biopsies revealed a normal endoscopic appearance of the bronchial mucosa. Fungal yeast forms and a colony of Aspergillus niger were isolated from the BAL but the biopsies showed no fungal structures, signs of rejection, or viral infection. Further microbiological studies ruled out infection by VIH, Nocardia, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Leishmania, and Cryptococcus. Diagnostic thoracentesis revealed a serohematic mononuclear exudate (96%), with negative tumor markers, adenosine deaminase 24U/l, interferon-gamma 10pg/ml, and flow cytometry without monoclonal peaks.

(a) Axial slice of a chest CT scan showing bilateral pleural effusion, larger on the right hemithorax, and multiple consolidations, some with air bronchogram and many with a peripheral ground-glass halo (largest nodule in the left lower lobe measuring 22mm×23mm). (b) Axial PET-CT image showing hypermetabolic pulmonary lesions with SUVmax of 10.26 in the left hilar and 8.56 in the right hilar lymph nodes. (c) Histological sections of Kaposi's sarcoma, hematoxylin–eosin stain ×4. (d) Anti-HHV-8 immunohistochemistry of the same histological section.

The main diagnostic suspicion was invasive fungal infection, with differential diagnosis including CMV pneumonitis, acute cellular rejection (ACR), or a lymphoproliferative disorder. Treatment with ganciclovir, anidulafungin, and voriconazole was initiated. After 15 days, a repeat chest CT showed a slight increase in bilateral pleural effusion without changes in the pulmonary lesions. Due to the lack of response, antifungal therapy was discontinued, and a PET-CT with 18-fluorodeoxyglucose was requested. In the PET-CT, the pulmonary lesions were hypermetabolic (Fig. 1b) and lymph nodes showed pathological uptake (hilar, retroperitoneal and subhepatic). The EBV viral load was undetectable. A CT-guided needle biopsy of the largest pulmonary nodule revealed findings consistent with Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) (Fig. 1c, d).

The patient experienced progressive clinical and respiratory deterioration during hospitalization, developing refractory respiratory failure related to disease progression. Given the advanced stage at diagnosis, reduction of immunosuppression was not feasible and did not contribute to the clinical decline. No autopsy was performed.

In the differential diagnosis of bilateral pulmonary infiltrates in a transplant patient, infectious causes should be considered first, including bacterial, viral, or fungal processes. Among the latter, invasive Aspergillus infection is particularly relevant in lung transplants, although other microorganisms such as Pneumocystis jirovecii, Cryptococcus neoformans, or fungal candidiasis should not be overlooked. Other causes of pulmonary infiltrates include acute lung rejection or oncological or lymphoproliferative processes.

Kaposi's sarcoma is an angioproliferative disease that requires infection with herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8). In lung transplant recipients, it can result from reactivation of HHV-8 in the recipient or transmission through the graft (the latter being less common). It is classified into four types based on the clinical context in which it develops, with particular emphasis on the iatrogenic form related to immunosuppressive therapy.1 Its incidence increases parallel to HHV-8 seroprevalence and is more common during the first months of immunosuppression and in young males.2 Ninety percent of affected patients present with cutaneous involvement,3 and only 10% have exclusive visceral involvement, a more severe form associated with higher mortality. Initial treatment involves reducing immunosuppression, though some patients benefit from chemotherapy.4 KS after lung transplant have been reported, but pulmonary KS is extremely rare in the literature.5,6

Given the high pretest probability of infection—supported by elevated immunosuppressive levels, a marked decline in lung function, and significant CMV viremia—the initial diagnostic approach focused on CMV pneumonitis while awaiting BAL cultures. Acute rejection was considered less likely and was subsequently ruled out by transbronchial biopsy. Although neoplastic or lymphoproliferative processes are always part of the differential diagnosis in transplant recipients, their lower frequency and the relatively short time since transplantation made them less probable in this context.

In conclusion, this case underscores the need to broaden the diagnostic approach in immunosuppressed patients, where uncommon or unexpected conditions may emerge and mimic more frequent post-transplant complications.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the manuscript preparation processArtificial intelligence was used only to assist in the English translation and language editing of the manuscript. All content, ideas, and conclusions were entirely generated and verified by the authors.

Informed consentWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case and accompanying images.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ contributionsL.O.R., B.P.C., C.S.C., J.M.I., A.D.P.G., R.A.M., M.T.T.O., and C.A.Q.L. participated in the clinical management of the patient. A.B.E.V. performed and reviewed the histopathological analysis. All authors contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare not to have any conflicts of interest that may be considered to influence directly or indirectly the content of the manuscript.