This article describes three models used around the world for the treatment of executory contracts in bankruptcy. An economic analysis is made of the ex post incentives of the bankruptcy trustee to reject the contract under each model, based on Jesse Fried's article Executory Contracts and Performance Decisions. This article states that the approach used by Spain is likely to create the most efficient ex post incentives. The contribution of this article is to further the discussion on the treatment of executory contracts in bankruptcy, as it continues to be one of the main day-to-day issues at bankruptcy courts.

Este artículo propone tres modelos de tratamiento de los contratos bilaterales pendientes de cumplimiento en el procedimiento de insolvencia11 Meaning “concurso mercantil.”

Executory contracts in bankruptcy are an issue of concern among legal scholars due to their economic importance and the complexity of their treatment. For the purposes of this article, executory contracts, as defined by Jesse Fried, are those contracts in which performance other than payment is owed by at least one party at the time of the filing of the bankruptcy petition.2 These contracts are particularly relevant in any bankruptcy proceeding because they are not entirely assets, nor exclusively liabilitie;3 instead, they imply an interrelationship between the debtor and the non-debtor party in which each of them enjoys some benefits and bears some costs. However, depending on the value of the contract, it can indeed represent an asset or a liability to the bankruptcy estate.

Because one of the main goals of bankruptcy worldwide is the maximization of the bankruptcy estate value, it is thought that bankruptcy law should ease the powers of the bankruptcy trustee to dispose of executory contracts.

The idea is to enable the bankruptcy trustee to seek performance of profitable contracts as well as to unburden the bankruptcy estate from unfavorable contracts. As a consequence, bankruptcy rules have usually been regarded as necessary to give the bankruptcy trustee broad discretion to assume and reject executory contracts, reducing the costs of rejection to the bankruptcy estate.

In 1996, Jesse Fried, in his seminal article “Executory Contracts and Performance Decisions”, challenged these traditionally accepted rules for the treatment of executory contracts by analyzing the incentives that American bankruptcy creates to inefficiently reject executory contracts.4 To be precise, the author shows that a regime that reduces the costs of rejection to the bankruptcy estate allows the externalization of costs to the non-debtor party which create inefficient incentives for the bankruptcy trustee to reject executory contracts that according to an efficiency perspective should be performed because performance would increase the total value to the bankruptcy estate as well as to the non-debtor party. Then, Jesse Fried proposes that, from an efficiency perspective, bankruptcy rules for rejection of executory contracts should be aligned with the social goal of maximization of total value.

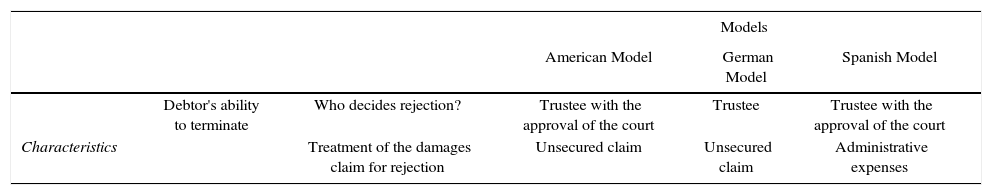

The purpose of this article is to contribute to the study of the rules for the treatment of executory contracts in bankruptcy by proposing a classification of the main approaches around the world, namely the American model, the German model and the Spanish model, and analyzing the incentives that these regimes create for the bankruptcy trustee ex post based on Jesse Fried efficiency analysis of executory contracts treatment in bankruptcy.

Table 1.

| Models | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Model | German Model | Spanish Model | |||

| Debtor's ability to terminate | Who decides rejection? | Trustee with the approval of the court | Trustee | Trustee with the approval of the court | |

| Characteristics | Treatment of the damages claim for rejection | Unsecured claim | Unsecured claim | Administrative expenses | |

Thus, this article concludes that the Spanish model is likely to create the most efficient incentives. Also it analyzes the possible objections to this model, namely that it is contrary to the principle of equal treatment among creditors and that it hampers the rehabilitation of the debtor. This article challenges these arguments; it finds that the argument of equal treatment is misplaced as bankruptcy law indeed allows for some exceptions to this principle on efficiency considerations for some other claimants. It also observes that this model does not hinder the rehabilitation of the debtor because despite enjoying administrative priority, the damage claims for rejection of executory contracts have to wait until the reorganization plan is confirmed to be satisfied. For all these reasons, this article advocates for consideration of the Spanish bankruptcy law by other bankruptcy systems as model to improve the treatment of executory contracts.

The study is organized as follows. Part II suggests a classification of the different approaches to the treatment of executory contracts in bankruptcy and describes the rules that characterize them. Part III examines the ability of the bankruptcy trustee to reject executory contracts under each of these approaches and the ex post incentives that it creates on the bankruptcy trustee. Based on such examination, this article argues that the Spanish model creates the most efficient incentives and, as a result, it is superior to the American and German models. Part IV analyzes the possible objections to the Spanish model. Part V draws a conclusion based on the results of this study.

IIThree ModelsEven though most bankruptcy laws all over the world include some rules for the treatment of executory contracts, it was necessary to find the most paradigmatic models that could facilitate a systematized analysis of the different approaches to the treatment of executory contracts. As the treatment of executory contracts becomes relevant only when the firm is expected to survive (usually in liquidation, the business is closed and all contractual relationships are terminated), only those countries where formal reorganization is available as part of a bankruptcy procedure were considered for this analysis. It should be noted that the classification of bankruptcy system presented in this article is only an effort to systematize the study of the treatment of executory contracts across different bankruptcy systems; thus it should only be considered as an effort to contribute to the discussion of bankruptcy rules in this area.

For the classification of bankruptcy systems that provide with reorganization rules in three models, two elements were taken into account: 1) Whether the bankruptcy trustee5 has limited or unlimited powers to reject executory contracts, where limited powers mean that it is necessary for the bankruptcy trustee to submit the decision to reject an executory contract to the bankruptcy court, and whether the bankruptcy court is likely to approve the bankruptcy decisions or not; and 2) whether the creditor's damages claim for rejection of an executory contract is treated as an unsecured claim or as an administrative expense.

The American bankruptcy law grants the bankruptcy trustee the power to assume or reject executory contract and submit such a decision to the authorization of the bankruptcy court, which is likely to approve the bankruptcy trustee's decisions; the damages claim for rejection is treated as an unsecured claim. It should be noted that the American bankruptcy system has become the paradigm all over the world in recent years, 6 particularly due to the rules for the reorganization of the debtor. For this reason, the first model proposed in this article is the American model.

Under the German bankruptcy law, the bankruptcy trustee has powers to assume or reject executory contracts without any limit imposed by the bankruptcy court; the damages claim for rejection is treated as an unsecured claim. It should be clear that the German bankruptcy system has also influenced other countries in terms of procedural structure and functioning of bankruptcy laws. 7 For this reason, the second model is the German model.

Last, but nor least, under the Spanish bankruptcy law, the bankruptcy trustee has the power to assume or reject executory contracts but such decision has to be approved by the bankruptcy court; the damages claim for rejection is treated as an administrative expense. This is the only bankruptcy system that treats a damages claim for rejection as an administrative expense.8 Therefore, Spanish bankruptcy law, at least in terms of executory contracts, is the most innovative one. For this reason, the third model is the Spanish model.

The following table summarizes with the elements that characterize each model in terms of executory contracts treatment in bankruptcy.

1The American ModelIn the United States, the bankruptcy system has been devised on the basis that the firm is more valuable as an ongoing concern tan sold in pieces;9 as a result, the rules tend to favor the debtor over its creditors. The idea is that, for the maximization of the debtor's assets, it is crucial to protect the debtor from being dismantled by its creditors.10

The main source of bankruptcy law in the United States is the Bankruptcy Code;11 section 365 of the code governs the treatment of executory contracts;12 those aspects not covered by statutory law are governed by case law.13

Trustee's ability to dispose of executory contractsExecutory contracts do not become part of the bankruptcy estate automatically. Section 365 of the Bankruptcy Code expressly provides that the bankruptcy trustee, who administers the bankruptcy estate, 14 can assume or reject executory contracts with the authorization of the bankruptcy court.15

aAssumptionIn order to bind the bankruptcy estate to an executory contract it is necessary for the bankruptcy trustee to assume it. Assumption makes the contract compulsory in its original terms and in its entirety to both the bankruptcy estate and the non-debtor party.16

The main effects of assumption are that all the obligations arising from the contract are treated as administrative expenses (because the contract is binding to the bankruptcy estate).17 If the bankruptcy estate breaches the contract's post-assumption, the non-debtor party is entitled to sue the bankruptcy estate for the loss suffered; the resulting damages claim for rejection is treated as administrative expenses.18 Because administrative expenses have a priority position over all other unsecured claims (administrative expenses have to be paid before any other unsecured claim), these claims are usually paid in full.19

bRejectionAlternatively, the bankruptcy trustee can choose to reject an executory contract; rejection is considered to be a prepetition breach by the debtor;20 thus, the non-debtor party is left with an unsecured damages claim.21 The main effect is that the damages claim for rejection has to share pro rata in the distribution of the debtor's assets with all other general unsecured creditors (unless the non-debtor party has a security interest in the debtor's assets);22 given that general unsecured claims are at the bottom of the priority ranking,23 the payout rate for these claims is frequently a small fraction of the total amount of the claim.24

The rationale for treating the damages claim for rejection as an unsecured claim under the American bankruptcy law is based on the bankruptcy policy of equal treatment and the maximization of the bankruptcy estate value.

Equal treatment and the maximization of the bankruptcy estate are explained as the solution to the creditor's collective action problem. To be precise, when the debtor is insolvent, there are not enough assets to pay its creditors in full; then, every creditor has incentives to dismantle the debtor in order to get full payment of the claim before the rest of the creditors (first come, first served rule).25 The consequence is that only a few creditors are paid in full while the rest of the creditors are paid zero; moreover, dismantling the assets of the debtor, reduces their value. Thus, bankruptcy law works as an implicit agreement, whereby, except for secured creditors, all creditors share equally in the distribution of the debtor's assets, and are paid a quantity proportionate to the actual amount of their claims.26

In this sense, treating damages claim for rejection as an unsecured claim furthers equal treatment among creditors and, in turn, the maximization of the bankruptcy estate value, as it makes it possible for the bankruptcy estate to unburden itself from unfavorable contracts.27

cTime limitExecutory contracts can be available for the bankruptcy trustee at any time before the confirmation of the reorganization plan.28

The bankruptcy trustee needs time to determine whether an executory contract is valuable or wasteful for the bankruptcy estate. Hence, the bankruptcy trustee usually delays assumption. For the non-debtor party, nonetheless, such delay may have undesirable effects because it prevents the non-debtor party from making future business decisions (it creates uncertainty).

Recognizing the detrimental effects that such delay may have on the non-debtor, the Bankruptcy Code provides that the non-debtor party is entitled to ask the bankruptcy court to require the bankruptcy trustee to decide assumption or rejection before the confirmation of the reorganization plan.

Despite this provision, bankruptcy courts are reluctant to force the bankruptcy trustee to make a decision due to the effects that assumption or rejection of an executory contract can have on all the debtor's creditors (as it may reduce or maximize the bankruptcy estate value).29

dCourt ApprovalAccording to the Bankruptcy Code, the bankruptcy trustee's decision to assume or reject a contract is submitted to the bankruptcy court for its approval.30 It should be noted that bankruptcy courts frequently grant a great deference to the bankruptcy trustee's business judgment.

Under the American bankruptcy system, the bankruptcy trustee is considered to know better how to administer the bankruptcy estate and how to maximize its value for the benefit of the debtor's creditors; for this reason, bankruptcy courts usually do not interfere with the trustee's activities and decisions.31 Moreover, bankruptcy courts’ role in authorizing or prohibiting assumption or rejection of an executory contract is limited because it is considered that, for the maximization of the bankruptcy estate value and rehabilitation of the debtor, it is necessary that the bankruptcy trustee enjoys some flexibility to make decisions, that is to say, this is a pro debtor bankruptcy system.

In the exercise of its discretion to administer the bankruptcy estate, the bankruptcy trustee owes a duty to maximize the value of the bankruptcy estate for the benefit of creditors;32 thus, when the bankruptcy trustee decides on assumption or rejection of an executory contract, indeed, it seeks the maximization of the bankruptcy estate value. In this sense, whether an executory contract is assumed or rejected is determined by whether the trustee sees the contract as beneficial or burdensome to the bankruptcy estate. If performance of a contract maximizes the value of the bankruptcy estate and facilitates the rehabilitation of the bankrupt company, the contract is likely to be assumed; conversely, if performance of a contract is burdensome to the bankruptcy estate or the value of the bankruptcy estate can be maximized by entering into a more favorable contract with a third party, the contract is likely to be rejected.33

Despite the great deference that bankruptcy courts usually grant to the bankruptcy trustee's decisions, it has been recognized that the bankruptcy trustee has incentives to reject contracts when rejection is harmful to the non-debtor party; for this reason there have been developed other judicial standards to authorize or deny rejection of an executory contract that are different from the “business judgment test”.34 Still due to the prevailing deference that bankruptcy courts grant to the bankruptcy trustee's business judgment, these standards are rarely used.

2The German ModelThe German bankruptcy law grants the bankruptcy trustee total authority to assume and reject executor contracts as the authorization of the bankruptcy court is not required; notwithstanding, the bankruptcy trustee's power to assume or reject executory contracts faces a particular limit: the non-debtor party is allowed to terminate some executory contracts. The effect of this rule has no impact on rejection but on assumption; this rule limits the bankruptcy trustee's power to assume contracts that are favorable to the bankruptcy estate but unfavorable to the non-debtor party.35

The rules for the treatment of executory contracts under the German bankruptcy law are based on the idea that the reorganization of a viable debtor is desirable and that reorganization requires the maximization of the value of the debtor's assets for the benefit of its creditors. However, the bankruptcy trustee's power to have executory contracts available is limited because bankruptcy is regarded under the German bankruptcy law as a procedure that facilitates the enforcement of creditor's rights against the insolvent debtor, that is to say, it is a pro creditor bankruptcy system.36

The main source of bankruptcy law in Germany is the Insolvency Code (Insolvenzordnung);37 Chapter II of Part III of this code governs the treatment of executory contracts.38

Trustee's ability to dispose of executory contractsUnder the German bankruptcy law, a bankruptcy case39 commences when the bankruptcy court40 orders bankruptcy relief rather than at the moment at which the bankruptcy petition is filed by the debtor or its creditors.41

From the moment of the bankruptcy filing to the time when bankruptcy relief is ordered, known as the “opening procedure”, an investigation is conducted by the bankruptcy court in order to determine the debtor's financial condition. The bankruptcy court employs experts to prepare a report about the financial condition of the debtor.42 Based on that report, if the bankruptcy court finds that the debtor is insolvent, it orders the commencement of the bankruptcy case.43

During this period, the debtor continues in operation but with several limitations to dispose of its assets, and no automatic stay is imposed on creditors to collect from the debtor.44 Likewise, contracts continue to be binding to the debtor and the non-debtor party; thus, both of them are obliged to continue performing their obligations under the contract.45 Because the effects of the bankruptcy procedure are triggered until relief is ordered, it is at this moment rather tan at the time of the bankruptcy filing that “executory contracts” 46 come into existence. According to the Insolvency Code, the bankruptcy trustee,47 who administers the bankruptcy estate, can reject executory contracts.48

a“Assumption”Under the German bankruptcy law, the bankruptcy estate is merely the result of the commencement of the bankruptcy case. The bankruptcy estate is not an entity different from the debtor.49 The debtor's property is levied for the benefit of all its creditors, but there is not a transfer of property because the debtor does not lose the title of property on its assets but the right to administer them and keep them at his disposal.

The bankruptcy estate encompasses all of the debtor's property (both at the time of the commencement of the bankruptcy case and acquired by the debtor during the procedure).50 Because the bankruptcy estate is not an entity completely different from the debtor, executory contracts become part of the bankruptcy estate automatically; in other words, executory contracts are valid and binding to the bankruptcy estate once the bankruptcy case commences but its effects are “suspended” until the bankruptcy trustee disposes of them.51

Even though all executory contracts are valid and binding to the bankruptcy estate,52 the German Insolvency Code requires that the bankruptcy trustee explicitly determines whether the executory contract is to be performed rather than rejected in order to protect the creditor's interests (right to be notified). To be clear, insolvency implies that the bankruptcy estate is limited to perform all executory contracts that if the bankruptcy trustee fails to take formal action to perform a contract (“assumption”), the contract is deemed to have been breached.

The effect of “assumption” is that the obligations related to performance of the contract by the bankruptcy estate become administrative expenses, which are priority claims.53 When an executory contract is “assumed”, it is binding to the bankruptcy estate and the non-debtor party in its original terms.54 If the bankruptcy estate breaches the contract post-assumption, the damages claim for breach is treated as administrative expenses as well.

It should be mentioned that the German Insolvency Code classifies the creditor's claims against the bankruptcy estate into four different categories in which administrative expense (included “creditors of the estate”) are over all other unsecured claims;55 as a consequence, these claims are usually paid in full.56 The justification for this rule is that performance of the contract is a claim that results from the administration of the bankruptcy estate; in fact, it is the bankruptcy estate the one which benefits from performance of the contract. Moreover, the non-debtor party is encouraged to continue in the contractual relationship by turning it into administrative expenses.

bRejectionThe bankruptcy trustee can choose instead rejection of the executory contract; then, the non-debtor party is entitled to compensation for damages but the claim is treated as a general unsecured claim.57 The damages claim for rejection has to share pro rata with other general unsecured claims (unless the non-debtor party has a security interest on any of the debtor's assets); general unsecured claims (insolvency claims) are at the bottom of the priority ranking, so they are frequently paid a fraction of the total amount of the claim.

The justification for treating the damages claim as a general unsecured claim is found in the bankruptcy policies of equal treatment and the maximization of the bankruptcy estate for the benefit of the debtor's creditors.

This bankruptcy system fosters the bankruptcy trustee's efforts to maximize the bankruptcy estate value by reducing the costs of rejection to the bankruptcy estate. The purpose is to facilitate rejection of those contracts that are unfavorable or burdensome to the bankruptcy estate. On the other hand, in the German bankruptcy system, the non-debtor party to a rejected contract is regarded as any other general unsecured creditor who has to share pro rata with all other unsecured creditors.58

cTime LimitThe German Insolvency Code does not impose a time limit for the “assumption” and termination of executory contracts; thus, it is implicit that the bankruptcy trustee can decide at any time before the confirmation of the reorganization plan.59

The decision about “assumption” and rejection of executory contracts usually takes some time, and the delay in making a decision may have a detrimental effect on the non-debtor party. Recognizing this situation, the German bankruptcy law enables the non-debtor party to ask directly the bankruptcy trustee to accelerate the decision on “assumption” or rejection of the contract.60 The effect of such request is that the bankruptcy trustee becomes obliged to decide “without negligent delay” about the disposition of the contract. If the bankruptcy trustee omits to take action within a reasonable time, then it is deemed that the bankruptcy trustee has rejected the contract.61

dTrustee's Business JudgmentThe German Insolvency Code gives complete discretion to the bankruptcy trustee to “assume” or reject executory contracts as no approval is required from the bankruptcy court.62 The rationale is that the bankruptcy trustee is supposed to know best how to achieve the maximization of the bankruptcy estate value. On the other hand, the German bankruptcy system is characterized by the control exercised by the debtor's creditors. 63 Then bankruptcy court supervises that the bankruptcy goals are effectively fulfilled, and intervenes whenever there is a conflict among the parties affected by bankruptcy case.64

3The Spanish ModelBankruptcy in Spain is ruled by the Insolvency Act (Ley Concursal),65 whose Chapter III of the Title III contains the rule on the treatment of executory contracts.66 The main purpose of the Spanish bankruptcy is the reorganization of the debtor as a means to maximize the value of the debtor's assets for its distribution among creditors.67On these grounds, the Spanish bankruptcy law gives the bankruptcy trustee the power to reject executory contracts.68

Trustee's ability to dispose of executory contractsUnder the Spanish bankruptcy law, a bankruptcy case commences at the time when the bankruptcy court69 orders bankruptcy relief rather than at the moment when the bankruptcy petition is filed.70

After the bankruptcy petition has been filed the bankruptcy court71 conducts an investigation on the financial condition of the debtor. However, unlike the German model, if the bankruptcy filing is voluntary, there is no need for a detailed investigation because for the bankruptcy court it is sufficent to examine the documents submitted by the debtor in order to find the grounds for bankruptcy relief. Conversely, if the bankruptcy is involuntary, the bankruptcy court instructs an expert to prepare a report. If the bankruptcy court finds that the debtor is insolvent, it orders the commencement of the bankruptcy case.72

During this first stage (after the bankruptcy petition has been filed but before the commencement of the bankruptcy case), the debtor continues in operation and no automatic stay is imposed on creditors to collect from the debtor.73 All contracts continue to be binding to the debtor and the non-debtor party, and, as a consequence, both of them are obliged to continue performing their obligations under the contract.

Because the effects of the bankruptcy procedure are triggered when the bankruptcy relief is ordered, it is at this moment rather than at the time of the bankruptcy filing that “executory contracts” come into existence.74

aAssumptionThe commencement of the bankruptcy case creates the bankruptcy estate but, under the Spanish bankruptcy law, the bankruptcy estate is not an entity with its own legal personality; instead, it is a pool of those assets that have been seized from the debtor for the benefit of its creditors.75 The bankruptcy estate encompasses all of the debtor's property,76 but the debtor does not lose the ownership of these assets; instead, a bankruptcy trustee is appointed to administer them.77

Because the commencement of the bankruptcy case does not create an entity different from the debtor, all executory contracts are part of the bankruptcy estate and are deemed to be valid and binding to both the bankruptcy estate and the non-debtor party.78 However, unlike the German bankruptcy law, as the debtor continues in operation, the effects of contracts are not suspended; instead, both the bankruptcy estate and the non-debtor party are obliged to continue performing their obligations under the contract in its original terms.79 In this sense, all executory contracts are automatically assumed. The main consequence of automatic assumption is that all the obligations related to performance of a contract are treated as administrative expenses, which have a priority position over all the other unsecured claims. Moreover, according to the Spanish bankruptcy law, administrative expenses have to be paid as they come due.80

bRejectionThe Spanish Insolvency Act provides that the bankruptcy trustee can reject a contract with the approval of the bankruptcy court.81 Considering that not all the contracts are valuable and many of them can be burdensome to the bankruptcy estate, the bankruptcy trustee can reject executory contracts with the approval of the bankruptcy court.82 Rejection, in this sense, means breach of the contract. The main effect of rejection is that the counterparty is entitled to damages compensation, which is treated as an administrative expense.83 This rule ensures that the non-debtor party is compensated in full for the loss of the expected gain from performance of the contract, because administrative expenses are paid before all other unsecured claims.84

Because this rule forces the bankruptcy estate to pay in full the damages claim for breach of the contract, it creates incentives for the bankruptcy trustee to choose not to reject (i. e. to perform) the contract when it increases the total value to both the promisor and the promisee (i. e. it prevents value wasting rejection). Likewise, this rule creates incentives for the bankruptcy trustee to choose breach of the contract when the cost of performance to the bankruptcy estate is greater than the benefit of performance to the non-debtor party (i. e. it prevents value wasting performance).

The Spanish bankruptcy law solves the conflict between this rule and the bankruptcy principle of equal treatment among creditors by providing that all executory contracts are automatically assumed. All contracts are deemed to be binding to the bankruptcy estate and as such all the obligations related to performance of contracts as well as the damages claim for rejection of a contract are the bankruptcy estate's liabilities. The non-debtor party to a contract then is not a creditor of the debtor but a creditor of the bankruptcy estate.85

cTime LimitNo time limit is imposed on the bankruptcy trustee to decide rejection of an executory contract. However, it is evident that the bankruptcy trustee can reject executory contracts before the confirmation of the reorganization plan, as it has to be approved by the bankruptcy court previous hearing of the non-debtor party, as it is to be explained below.

It is important to notice that time limits are imposed in most bankruptcy systems with the purpose of limiting the bankruptcy trustee's authorityre to assume and reject executory contracts (it reduces the uncertainty in the non-debtor party's rights and obligations with respect to the performance of a contract). In this model, time limits for the trustee to dispose of executory contracts are somewhat irrelevant as all executory contracts are automatically assumed. Specifically, both the bankruptcy estate and the non-debtor party have to continue performing the contract in its original terms as long as the bankruptcy trustee does not reject the contract. Moreover, if the contract is breached by the bankruptcy estate, the claim for damages is granted an administrative priority, which ensures that the non-debtor party is compensated in full.

dCourt ApprovalUnder the Spanish bankruptcy law, the bankruptcy court has the control of the bankruptcy procedure; for this reason, the Spanish Insolvency Act mandates that the bankruptcy trustee's decision to reject an executory contract is subject to the authorization of the bankruptcy court.

Unlike other bankruptcy systems, the bankruptcy court's authority to approve or prevent rejection of executory contracts prevails over the bankruptcy trustee's business judgment; thus, the bankruptcy's trustee decision is not sufficient to breach a contract.

According to the Spanish Insolvency Act, once the bankruptcy trustee request rejection of an executory contract, the bankruptcy court summons the bankruptcy trustee, the debtor, and the non-debtor party for a hearing. In such a hearing, the bankruptcy court mediates between the parties. If the bankruptcy trustee and the non-debtor party do not reach agreement on the rejection of the contract, the conflict is solved in a collateral proceeding.86 The bankruptcy court decides on rejection of the contract depending on whether performance or breach of a contract is favorable to the bankruptcy estate.87

IIIThe Superiority of the Spanish modelThis part examines the incentives that each model creates for the bankruptcy trustee and the non-debtor party to perform or terminate executory contracts ex post as well as the debtor's and creditors’ incentives to invest and file for bankruptcy ex ante.

The treatment of executory contracts and its effects in efficiency terms has been examined by American scholars in previous studies.88 Such analyses have demonstrated that the externalization of costs by the bankruptcy estate when an executory contract is rejected leads to inefficient results.89

Based on such findings, this part examines and compares the rules on the treatment of executory contracts under American model, the German model, and the Spanish model. The part argues that the regime adopted by the American and German models is undesirable as it facilities the externalization of costs by the bankruptcy estate to reject executory contracts, creating inefficient incentives for the bankruptcy trustee ex post as well as for the debtor and its creditors ex ante. It also argues that the Spanish model, which adopts a regime that forces the bankruptcy estate to internalize the costs of rejection, creates the most desirable results both ex post and ex ante.

Finally, this part argues that because the rules on the treatment of executory contracts adopted by the Spanish model create the most desirable incentives for the bankruptcy trustee, this model is superior to the American and German models.

Ex post Efficiency to RejectAssumption or rejection of executory contracts is part of the ordinary decisions that the bankruptcy trustee has to make in the administration of a bankruptcy estate.

Some bankruptcy systems, as it is the case of the American model and the Spanish model, impose a judicial limit on the bankruptcy trustee's discretion to dispose of executory contracts because the decision to assume or reject executory contracts is subject to the approval of the bankruptcy court. In spite of these judicial limitations, the bankruptcy trustee is the one who has the initiative to assume or reject contracts.

aThe Possibility of Inefficient RejectionThis part intends to establish if, from an efficiency perspective, there is a regime for the treatment of the damages claim for rejection likely to create the best incentives for the bankruptcy trustee to make decisions on assumption or rejection of executory contracts that result in an increase in the value available to all the parties affected rather tan exclusively to the bankruptcy estate.

The rules for the treatment of the damages claim for rejection determine the bankruptcy trustee's incentives to assume or reject an executory contract. The bankruptcy trustee chooses assumption or rejection of an executory contract depending on whether the contract is valuable or burdensome to the bankruptcy estate, which in turn is determined by the value of the contract and cost of performance to the bankruptcy estate. However, as explained by Jesse Fried, from an efficiency perspective it is desirable that assumption or rejection of executory contracts is decided on whether a contract increases total value (the value to both the bankruptcy estate and the non-debtor party).90

a)Contract Law and Efficient Breach— Damages Claim for BreachBesides bankruptcy, the promisor has the option to perform or breach the contract just as it happens in bankruptcy with the bankruptcy trustee's opportunity to assume or reject an executory contract.

When two parties enter into a contract, some value is created so that both the promisor and the promisee are better off. Due to this value it is desirable to make a promise enforceable and to provide the promisor with remedies to ensure the enforcement of the promise. The most common remedy available in contract law to the promisee is damages compensation. Damages compensation consists in forcing the promisor to pay an amount of money to the promisee equal to the loss the promisor suffers as a result of breach of the contract (or equal to the gain the promisee would have realized on performance of the contract).91 Forcing the promisor to compensate the promise in full creates efficient incentives for the promisor to perform a contract, because it prevents such party from externalizing costs to the promisee and it preserves the value that is created when an exchange takes place.92

Had contract law not force the promisor to internalize the cost of breach in full, a promisor would simply breach contracts at the expense of the promisee; that is to say, the promisor would enjoy all the benefits without paying the amount due to the promisee, because reaping all the benefits and externalizing the costs makes the promisor (agent) better off.

— Efficient BreachForcing the promisor to pay in full the damages claim for breach gives the promisor efficient incentives to breach a contract when the cost of performance to the promisor is greater than the value of the contract to the promisee (to be precise, it creates incentives for the promisor to breach when performance is value-wasting). This doctrine is known as the theory of the efficient breach.93

b)Bankruptcy Law and the Damages Claim for RejectionThe logic of the trustee's power to assume or reject an executory contract is no different from the promisor's option to perform or breach a contract outside of bankruptcy.94 However, in bankruptcy, the assets are not sufficient to pay in full every claim, therefore creditors share pro rata the debtor's creditors. This principle is known as “equal treatment among creditors.”95

— Damages Claim for Rejection as an Unsecured claimIn the American model and the German model, the damages claim for rejection has to be paid as a prepetition unsecured claim, and, as a consequence, the damages claim from rejection shares pro rata with other prepetition unsecured claims. 96

This rule has usually been justified in these bankruptcy systems on the basis that it is in harmony with the principle of equal treatment among creditors in bankruptcy. As mentioned above, in bankruptcy the lack of sufficient assets to be distributed among the debtor's creditors limits the bankruptcy estate's ability to compensate in full the non-debtor party for the loss suffered when the bankruptcy estate rejects an executory contract; thus, as any other unsecured creditor, the non-debtor party's damages claim for rejection has to share with all other unsecured claims.97

This rule is also justified on the basis that it furthers the rehabilitation of the debtor and the maximization of the bankruptcy estate value. This conception considers that it is desirable to treat the damages claim for rejection as a general unsecured claim because it eases the rejection of those contracts that are burdensome to the bankruptcy estate. To be clear, it is necessary to enable the trustee to perform contracts that are beneficial for the estate and unburden the bankruptcy estate from unfavorable contracts that pose an obstacle to the maximization of the bankruptcy estate value.98

An alternative explanation for this rule is that the damages claim arises from the rejection of a contract in which the parties had entered into before the bankruptcy petition was filed —or the bankruptcy case is commenced. Consequently, as any prepetition claim, the damages claim has to share pro rata with all other unsecured claims in the distribution of the assets; otherwise, the non-debtor party to an executory contract would be treated differently from all the other general unsecured creditors.

— Rejection of Burdensome ContractsFrom an efficiency perspective, rejection of burdensome contracts is efficient when performance is value-decreasing. Executory contracts are burdensome to the bankruptcy estate when the cost of performance is larger than the value of the contract to the bankruptcy estate; likewise, performance is wasteful when the cost of performance to the bankruptcy estate is greater than the value of the contract to the non-debtor party.

The rejection of a burdensome contract is efficient and consistent with the goal of the maximization of the value of the bankruptcy estate for the benefit of the debtor's creditors when performance is wasteful, because the gain from rejection to the bankruptcy estate is greater than the loss imposed on the non-debtor party. In other words, if the trustee decides to assume the contract, the loss from performance to the bankruptcy estate is greater than the gain that the non-debtor party obtains.99

— Possible Inefficient RejectionHowever, treating the damages claim for rejection as an unsecured claim has proved to produce undesirable effects because it creates incentives for the trustee to excessively reject executory contracts, even though some of these contracts create some value for the benefit of both the bankruptcy estate and the counterparty.100 To be clear, this rule causes a bias towards rejection regardless of whether a contract is wasteful or value-creating, because under this rule the bankruptcy estate does not fully internalize the costs of rejection.

A contract is value-creating when it increases the total value available to both the bankruptcy estate and the non-debtor party; that is to say, when the cost of performance to the bankruptcy estate is less than the benefits the contract creates for the non-debtor party; to put it differently, the gain from rejection to the bankruptcy estate is less than the loss imposed on the non-debtor party if the contract is rejected; a contract is value-creating because performance increases the total value to both the bankruptcy estate and the non-debtor party.101

The rejection of value-creating contracts is inefficient because the loss from rejection to the non-debtor party is greater than the cost of performance to the bankruptcy estate; in other words, the benefit from rejection to the bankruptcy estate is less than the loss that the non-debtor party suffers as a result of rejection of the contract. Rejection of a value-creating contract then is inefficient because the value that performance of the contract would create for the benefit of both the bankruptcy estate and the non-debtor party is lost.102

This rule is problematic from an efficiency perspective because the cost of rejection is always lower than the cost of assumption. When the damages claim for rejection is treated as an unsecured claim, the damages claim is paid on a pro rata basis, whereas the obligation arising from the assumed contract and any damages claims arising from post-assumption breach of such contract have to be paid in full. The difference in the cost of performance and the costs of breach creates a bias towards rejection, even if the contract is value-creating.103

c)Damages Claim for Rejection as Administrative ExpensesUnlike the other models, the Spanish model adopts a rule in which the damages claim for rejection of executory contracts is treated as administrative expenses. This rule ensures that the non-debtor party is compensated in full for the expected gains lost as a result of rejection of the contract. The effects of this rule are similar to those of paying in full the damages for breach in contract law. Because the bankruptcy estate is forced to fully internalize the costs of rejection, the bankruptcy trustee has the efficient incentives to choose assumption of the executory contract when performance is value-creating and chose rejection of the executory contract when performance is value-wasting.104 This rule attacks the origin of the externalization of costs by the bankruptcy estate, as well as the bankruptcy trustee's bias towards the rejection; in this sense, the expectation damages rule creates the same efficient incentives for the bankruptcy estate to make performance decisions as contract law creates efficient incentives for the promisor to make performance decisions outside of bankruptcy.

Treating damages claim for rejection as administrative expenses prevents the bankruptcy trustee from rejecting an executory contract when the loss imposed on the non-debtor party is greater than the benefit obtained be the bankruptcy estate because the bankruptcy estate is forced to internalize the costs of rejection to the non-debtor party. Similarly, this rule creates efficient incentives for the bankruptcy trustee to reject when performance is wasteful, that is when the benefit to the non-debtor party is less than the cost of performance to the bankruptcy estate. Again, the reason is that the bankruptcy estate has to internalize in full the costs of rejection to the non-debtor party. This rule creates more certainty about the fate of the contract for the non-debtor party, because the bankruptcy estate is obliged to pay the non-debtor party in full in either case: assumption or rejection.

IVObjectionsAs explained above, the Spanish model creates the most efficient incentives for the bankruptcy trustee ex post. However, this model may create other sort of problems, namely: a) it violates the principle of equal treatment among creditors, and b) it may hamper the rehabilitation of the debtor.105

1FairnessThe main objection against granting the damages claim for rejection as the administrative priority is that it is contrary to the principle of equal treatment among creditors.106

Granting the damages claim for rejection of an executory contract has already been analyzed as a solution for the distortions created by the ratable damages rule, which is the approach adopted in most bankruptcy systems.

Legal scholars have acknowledged that forcing the bankruptcy estate to internalize in full the costs of rejection eliminates the distortions created by the ratable damages rule because it creates incentives for the bankruptcy trustee to choose rejection of the contract only when the cost of performance to the bankruptcy estate is greater than the benefit to the non-debtor party (i. e. the administrative priority rule prevents wasteful rejection). However, it has been argued that this measure is problematic because it is contrary to one of the main bankruptcy policies: equal treatment among creditors.107

In bankruptcy, except for unsecured creditors, all the debtor's creditors have to share pro rata in the distribution of the debtor's assets among them because the debtor's assets are not sufficient to pay all the claims in full. Since the administrative priority rule forces the bankruptcy estate to pay in full the damages claim for rejection (rather than a proportionate amount according to the assets available in bankruptcy), it disregards the principle of equal treatment among creditors.

Such conception has its basis on the idea that bankruptcy is a procedure that facilities an orderly payment to the debtor's creditors when the debtor is insolvent. Because an insolvent debtor has not sufficient assets to pay its creditors in full, bankruptcy ensures equal distribution of the value of the debtor's assets among creditors.

From an economic perspective, the principle of equal treatment is justified on the basis that bankruptcy as a solution to the creditor's collective action problem.108 According to this theory, when the debtor is insolvent, creditors have incentives to grab the debtor's assets to satisfy their claims in full before no assets are left. However, this behavior makes creditors worse off as a group because only those who individually collect first from the debtor are paid in full, whereas the remaining creditors receive nothing.109 Creditors would be better off if they could renegotiate the terms of the debt and defer payment of their claims until the firm produced more income to be able to meet its obligations, or if they could agree to divide ratably the value of the firm so that all of them could receive some value to satisfy their claims. Nevertheless, bargaining costs are prohibitively expensive for creditors to enter into such agreement because creditors are dispersed and have an interest to maximize their claims individually. Hence, bankruptcy law provides the rules that creditors would negotiate if they could enter into a contract to distribute equally the value o the debtor among them according to their non-bankruptcy entitlements and, if possible, seek the rehabilitation of the debtor110.

Granting an administrative priority to the damages claim for rejection then is regarded as unfair because contractual creditors, unless they have a secured interest in the debtor's assets, should share pro rata in the distribution of the value of the debtor's assets as any other unsecured creditor. It is argued that when the damages claim for rejection of an executory contract enjoys an administrative priority some value is transferred to the non-debtor party at the expense of all other unsecured creditors. Unlike all other unsecured claims, a claim that enjoys an administrative priority is paid first all other unsecured creditors and as such is usually paid in full.Likewise, from a traditional view, granting ad administrative priority to the damages claim for rejection violates the principle of equal treatment because it disregards the implicit agreement among the debtor's creditors to distribute the firm's value ratably among them.

Nevertheless, the principle of equal treatment among creditors should be flexible when both the bankruptcy estate and all the debtor's creditors are benefited; in other words, it is valid to make an exception to this principle of equal treatment among creditors when the strict use of this principle has detrimental effects on both the debtor and its creditors. From an economic perspective, this is explained in these terms: this rule creates inefficient incentives on the bankruptcy trustee to obtain some benefit for the bankruptcy estate at the expense of the non-debtor, not to say that it creates other inefficiencies besides bankruptcy; this is the reason why bankruptcy law grants a priority position to certain types of claims.111

For example, under the American Bankruptcy Code, the claims of tort creditors are in a higher priority position than all other general unsecured creditors. The justification is that tort creditors become creditors of the debtor involuntarily. Thus, these creditors cannot make the debtor internalize the risk of loss, which creates incentives for the debtor to engage in excessively risky activities that reduce the expected value of creditors’ claims which is aggravated when the debtor is insolvent and bankruptcy is certain. Moreover, even though the debtor can be forced to take insurance against tort damages, the debtor has incentives to undersecure. Thus, bankruptcy law intends to deter such behavior by granting tort claims an administrative priority s that the debtor internalizes the cost of its activities.

Although equal treatment among creditors is one of the pillars of bankruptcy law, an exception to this principle should be valid on the grounds of efficiency, because in the end the purpose is to align the goals pursued by bankruptcy law with the social of maximization of total value.

It is important to notice that fairness concerns could be mitigated with a procedural solution as it is the case of the Spanish model. The Spanish Insolvency Act mandates that all executory contracts are deemed to be automatically assumed by the bankruptcy estate. By mandating automatic assumption of all contracts, all those parties to executory contracts become creditors of the bankruptcy estate (these creditors are no more prepetition unsecured creditors of the debtor); as a consequence, the non-debtor party is not anymore a prepetition unsecured creditor of the debtor but a post-petition creditor of the bankruptcy estate.

2RehabilitationThe second objection to a regime for the treatment of the damages claim for rejection that adopts the administrative priority rule is that it hampers reorganization.

The traditional explanation of the rules on the treatment of executory contracts is that the duty of the bankruptcy trustee is the maximization of the bankruptcy estate. When a firm enters bankruptcy, it is common that some of the contracts remain unperformed and some of these contracts impose a burden to the bankruptcy estate. Because one of the underlying goals in bankruptcy is reorganization of the debtor, it is desirable to allow the bankruptcy trustee to reject those contracts that are unfavorable to the bankruptcy state.

It is regarded as necessary to enable the bankruptcy estate to unburden itself from unfavorable contracts in order to maximize the bankruptcy estate value; once the bankruptcy estate is released from those contracts, the bankruptcy trustee can seek to enter into contracts with third parties in more favorable terms for the bankruptcy estate, and even if the bankruptcy estate does not enter in new contracts with third parties, rejecting burdensome contracts benefits the bankruptcy estate as it releases the bankruptcy estate from loosing some value.

In this sense, reducing the costs of rejection is justified on the basis that it facilitates rejection of burdensome contracts, which in turn facilitates the maximization of the bankruptcy estate value. Conversely, a regime that forces the bankruptcy estate to fully internalize the costs of rejection is regarded as undesirable because it makes it more difficult for the bankruptcy estate to unburden itself from unfavorable contracts due to the asset constraints in bankruptcy.

Notwithstanding, the administrative priority granted to the damages claim for rejection is unlikely to affect the rehabilitation of the debtor, because payment damages claims can be deferred until the reorganization plan is confirmed. In this sense, although the amount of the damages claim for rejection of executory contracts are larger under the expectation damages rule, such claims are paid out at the end of proceeding.112

VConclusionsThis article has examined the main approaches to the treatment of executory contracts used around the world for the treatment of executory contracts in bankruptcy focusing on the ability and incentives of the bankruptcy trustee to reject executory contracts.

After classifying such regimes into three models, this article has described the rules on the treatment of executory contracts under each model. Based on previous studies on executory contracts from an economic perspective, this article has analyzed the incentives that these regimes create ex post for the bankruptcy trustee.

This article has demonstrated that the American model, which adopts a regime in which the damages claim for rejection of executory contracts is treated as a general unsecured claim, creates inefficient incentives for the bankruptcy trustee to reject value-creating contracts. As for the German model, this article has shown that it adopts a regime in which the damages claim for rejection is treated as a general unsecured claim, produces the same inefficiencies as those generated by the American model. Last but not least, this article has found that the Spanish model is likely to create the most efficient incentives ex ante and ex post for the debtor and the non-debtor party to make decisions on performance, investment and filing for bankruptcy. Unlike the American and German models, the Spanish model adopts a regime in which the damages claim for rejection enjoys administrative priority which forces the bankruptcy estate to internalize the costs of rejection.

This article has also analyzed several objections to the Spanish model, namely that it is contrary to the principle of equal treatment among creditors and that it hampers rehabilitation of the debtor. This study has concluded that these objections are misplaced and that an exception to the principle of equal treatment should be allowed.

Based on the results of this study, this article argues that the Spanish model is superior to the American and German model and advocates for its consideration as a model for other bankruptcy systems to improve the treatment of executory contracts.

Professor of Law, Facultad de Derecho & Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas, National Autonomous University of Mexico (unam), Mexico. This article is part of the JSD dissertation submitted to UC Berkeley, Law School. I am indebted to Professor Jesse Fried for his invaluable comments and mentoring. I would also like to express my gratitude to Carla Barrerra Díaz de la Vega for her priceless help to make this article possible. I am also very grateful to Rodrigo Aguilar, Víctor Díaz, Gabriela Guzmán, Miguel Ángel Lemus, Diana Monterrubio and Daniela Sánchez for their excellent research assistance.

Meaning “concurso mercantil.”

Jesse M. Fried, Executory Contracts and Performance Decisions 46 in Duke L. J. 517 (1996).

An alternative way to state it is that executory contracts “are nothing more tan mixed assets and liabilities arising out of the same transaction.” See Thomas Jackson, The Logic and Limits of Bankruptcy Law 106 (1986).

There are previous studies on executory contracts that focus on the unpredictable consequences for the bankruptcy trustee and the non-debtor party as a result of the lack of a definition of the executory contract under Section 365 of the American Bankruptcy Code. The prevailing definition in case law is the one proposed by Vern Countryman during the 1970's. According to this legal scholar, an executory contract is “a contract in which the obligation of both the bankruptcy and the other party to the contract are so far unperformed that the failure of either to complete performance would constitute a material breach excusing the performance of the other.” See Vern Countryman, Executory Contracts in Bankruptcy: Part I 57 in Minn. L. Rev. 439, 460 (1973). But such definitions are so confusing that it is unpredictable whether a contract will be regarded as executory or not in bankruptcy. Thus, legal commentators have advocated for the inclusion of a clearer definition such as the one proposed by Michael T. Andrew or for the elimination of “executoriness” as proposed by Jay L. Westbrook. See Michael T. Andrew, Executory Contracts in Bankruptcy: Understanding “Rejection,” 59 (U. Colo. L. Rev. 845) (1988); Jay L. Westbrook, A Functional Analysis of Executory Contracts 74 (Minn. L. Rev. 227) (1989). Some other studies have demonstrated that the current regime under the Bankruptcy Code is undesirable because it distorts the incentives for the debtor and the non-debtor party to make investment and performance decisions ex ante and ex post. See George Triantis, The Effects of Insolvency and Bankruptcy on Contract Performance and Adjustment 43 (U. Toronto L.J. 679) (1993); Fried, supra note 2; Alon Chaver & Jesse M. Fried, Managers Fiduciary Duty upon the Firm's Insolvency: Accounting for Performance Creditors 55 (Vand. L. Rev. 1813) (2002). Peter Menell focused on the detrimental effects of rejection of intellectual property licenses in bankruptcy. See, Peter S. Menell, Bankruptcy Treatment of Intellectual Property Assets: An Economic Analysis 22 (Berkeley Tech. L.J. 733) (2007). For recent general studies about rejection of executory contracts in bankruptcy, see George G. Triantis, Jumping Ship: Termination Rights in Bankruptcy: The Story of Stephen Perlman v. Catapult Entertainment, Inc., in Bankruptcy Law Stories 55, 68 (Robert K. Rasmussen ed. 2007). Carl N. Pickerill, Executory Contracts Re-Revisited 83 (Am. Bankr. L.J. 63) (2009).

The term “bankruptcy trustee” applies to all the models proposed in this article and refers to the person in charge of administering the “bankruptcy estate.”

For example, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, Japan, Korea, and Mexico, to name only a few.

For example, Japan and Mexico.

It should be noted that the Spanish bankruptcy system was modified last decade; it included an improved version of the US Chapter 11 reorganization based on the suggestions provided by American scholars on this topic.

Whether the going concern value of the firm is higher than the liquidation value depends on two factors: a) the assets in combination should be worth more than if sold in pieces, and b) when a prompt liquidation is no more beneficial for the group as a whole rather than a long proceeding in which some creditors will take advantage at the expense of the others. See Thomas H. Jackson & Robert E. Scott, On the Nature of Bankruptcy, An Essay on Bankruptcy Sharing and the Creditors’ Bargain 75 (Va. L. Rev. 155, 159) (1989).

It should be noticed that although bankruptcy rules are devised to protect the debtor, the objective is to increase the value of the debtor's assets for the benefit of creditors. For an explanation of the role of bankruptcy law on the grounds of the creditor's collective action problem, see Jackson; supra note 3, at 7-19.

The title 11 of the United States Code or “Bankruptcy Code” is not the only one statutory source of bankruptcy law such the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure and the Official Bankruptcy Forms issued by the Supreme Court, as well as provisions related to bankruptcy law found in other statutes such as in titles 28 and 18 of the United States Code.

Liquidation is governed by Chapter 7 of the Bankruptcy Code; whereas reorganization is governed by Chapter 11 of the same code. It should be noticed that, under the American bankruptcy law, liquidation and reorganization are two separate proceedings, but section 365 covers the treatment of executory contracts regardless of the type of bankruptcy proceeding. For the purposes of this study, however, only reorganization cases are analyzed. The reason is that the disposition of executory contracts in liquidation cases is somewhat restrained. In Chapter 7 on liquidation proceedings, executory contracts are deemed to be automatically rejected unless the trustee requests the authorization of court to assume a contract within sixty days after the order for relief is issued. See 11 U.S.C §365(d)(1).

Case law is an important source of law in the United States. Bankruptcy law is not an exception; indeed, section 105 of the Bankruptcy Code provides that bankruptcy courts “may issue any order, process, or judgement that is necessary or appropriate to carry out the provisions of this title.” Id., §105 (a).

The bankruptcy trustee is the person in charge of administering the bankruptcy estate. Id., §§1104 and 1302. Under the American bankruptcy law, the debtor’s managers may remain in the administration of the bankruptcy estate with the same powers of those of a trustee, which is known as the debtor-in-possession (DIP). Id., §1107.

Section 365 states that the trustee may assume or reject executory contracts or unexpired leases. See 11 U.S.C §365 (a). Although this study focuses exclusively on assumption and rejection, the bankruptcy trustee can assign an executory contract to a third party once it has been assumed. Id., §365(f)(1).

In this sense, if there has been a prepetition default of the debtor, an executory contract cannot be assumed unless the bankruptcy trustee cures such default, compensates the non-debtor party for any actual pecuniary loss suffered and provides adequate assurance of future performance. Id., §365 (b)(1). For the purposes of this study, it is assumed that there is no prepetition default of the debtor.

This includes the payments made to cure and compensate for prepetition default.

Id., §365(g)(2).

Id., §§507(a)(1), 503(b); Fried, supra note 2, at 525.

See 11 U.S.C. §365(g)(1). It has to be mentioned that there is a serious controversy about the meaning and effects of rejection. See Michael T. Andrew, supra note 4; Jay L. Westbrook, supra note 4.

See 11 U.S.C §502(g).

See Fried, supra note 2, at 519.

See 11 U.S.C §507(a).

See Fried, supra note 2, at 525.

See Jackson; supra note 3, at 7-19.

Id.

To illustrate this statement, suppose that Firm and Ad Agency have entered into an advertising agency contract in which Firm has agreed to pay $100 to ad Agency to launch an advertising campaign for a Firm's new product. Suppose further that Firm files for bankruptcy. At the time the bankruptcy petition is filed, Firm has not paid $100, and Ad Agency has not incurred any expenses in producing the advertising campaign for the Firm's new product. Suppose that the contract represents $80 of value to the bankruptcy estate. The bankruptcy trustee is considering whether to assume or reject the contract. Assume that the expected payout rate for unsecured claims is of 30%. If the bankruptcy trustee rejects the contract, the bankruptcy estate has to pay $9 for damages to Ad Agency because the bankruptcy estate only has to pay 30% of $30 (which is the expected gain from performance to Ad Agency, $100 that would be paid in Exchange of the advertising campaign, less $70 that it would cost to Ad Agency to produce it); whereas if the bankruptcy trustee assumes the contract, it will cost $20 to the bankruptcy estate to perform ($100 that has to pay Ad Agency, less $80 of value that the contract creates for the benefit of the bankruptcy estate). The contract represents a burden to the bankruptcy estate because performance of the contract imposes a loss of $20 to the bankruptcy estate; thus, the bankruptcy trustee is likely to reject the contract because the cost of performance is greater tan the cost of rejection. As it can be observed, treating the damages claim for rejection as an unsecured claim reduces the costs of rejection because the bankruptcy estate only has to pay 30% of the loss that Ad Agency suffers from rejection of the contract. Because the damages claim is never paid in full under this rule, rejection is always less costly tan performance of the contract. In this case, the $9 fee for damage compensation that the bankruptcy estate has to pay to Ad Agency, if the contract is rejected, should be compared to the $20 loss imposed on the bankruptcy estate, if the contract is performed. Thus, this rule makes it easy for the bankruptcy estate to unburden itself from unfavorable contracts. This numerical example is based on those used by Jesse Fried. See Fried, supra note 2.

See 11 U.S.C. 365(d)(2).

Id. It should be mentioned that there are cases in which the bankruptcy trustee does not make a formal decision about assumption or rejection of an executory contract; however, the Bankruptcy Code is silent about this issue. Bankruptcy courts have generally considered that, if the bankruptcy trustee fails to take formal action on assumption or rejection of an executory contract, the contract “rides through” reorganization and the contract continues to be binding to the debtor. See Charles Jordan Tabb, THE LAW OF BANKRUPTCY §8.3 (1997). Because formal decision to assume or reject an executory contract is necessary under the American bankruptcy law, the condition of an executory contract and its actual assumption or rejection are also uncertain after the bankruptcy petition has been filed. For a discussion on executory contracts in the “gap period”, see Douglas W. Bordeweick, The Postpetition, Pre-Rejection, Pre-Assumption Status of an Executory Contract 59 (Am. Bankr. Dev. J. 421) (1982). See Continental Country Club, Inc. v Burr (In re Continental Country Club, Inc.) 114 (B.R. 763) (Bankr. M.D. Fla. 1990); Central Control Alarm Corp. v Black (In re Central Watch, Inc.) 22 (B.R. 561) (Bankr. E.D. Wis. 1982); International Union of United Auto., Aerospace & Agric. Implement Workers v. Miles Mach Co. 34 (B.R. 683) (Bankr. E.D. Mich. 1982).

See 11 U.S.C. 365 (a).

See Fried, supra note 2, at 540.

Id., at 518

See Steven J. Wadyka Jr., Executory Contracts And Unexpired Leases: Section 365, 3 (Bank. Dev. J. 217, 217) (1986).

These tests have been labeled by Jesse Fried as “the burdensome test” and “the balancing test.” Under this standard, the bankruptcy court prevents the bankruptcy trustee from rejecting an executory contract, only if rejection causes “an absolute reduction in the value of the estate.” Thus, the bankruptcy trustee can only reject a contract if the contract imposes a loss on the bankruptcy estate. Under this standard, the bankruptcy court prevents the bankruptcy trustee from rejecting an executory contract only if the loss from rejection to the counterparty is not disproportionately greater than the benefit obtained by the bankruptcy the bankruptcy estate. Thus, the bankruptcy court cannot prevent rejection from imposing minimal losses on the non-debtor party, even though rejection in such a case is equally wasteful. See Fried, supra note 2, at 540-542.

The analysis of postpetition termination by the debtor's creditors is beyond this article.

The rationale is that there is still a stigma attached to insolvency. This stigma of insolvency is ancient and can be traced back to the Roman law. In Rome, insolvency was severely punished, even with incarceration. See Eckart Ehlers, Germany Statutory Corporate Rescue, at CORPORATE RESCUE, 80-81 (Katarzyna Gromeck Broc & Rebecca Parry eds., Kluwer Law International, 2004). Even though this conception of insolvency is changing, the stigma is still alive (for example, section 1 of the German Insolvency Code which states that “honest debtors shall be given the opportunity to achieve discharge of residual debt.” InsO §1). See Christoph G. Paulus, The World Bank Principles in Comparison with the New German Insolvency Statute, 2. Section 1 of the German Insolvency Code provides that: “The insolvency proceedings shall serve the purpose of collective satisfaction of a debtor's creditors by liquidation of the debtor's assets and by distribution of the proceeds, or by reaching an arrangement in an insolvency plan, particularly, in order to maintain the enterprise.” Insolvenzordnung (InsO) 5.8.1994 (BGB1. I S.2866) [hereinafter InsO] (1999) (Gr.) Whether a firm should be liquidated or reorganized is determined by creditors and depends on how to best maximize creditors’ claim value, rather than whether a firm is viable or unviable; this conception is usually called “Creditor control” (Gläubigerherrschaft). See InsO §157; Lies, Gerald I., Sale of a Business in Cross-Border Insolvency: The United States and Germany 10 (Am. Bankr. Inst L. Rev. 363, 377) (2002); Kamlah, Klaus, The New German Insolvency Act: Inzolvenzordnung, 70 Am. Bankr. L.J. 417, 422 (1996).

The German Insolvency Code was passed in 1994 but that came into effect in its entirety until 1999. See Axel Fressner, National Report for Germany, 4 PRINCIPLES OF EUROPEAN INSOLVENCY LAW, 314 (Mc Bryde, W. W. et al, ed., Kluwer Legal Publishers, 2003). It should be mentioned that in Germany there are other statutes that are relevant for bankruptcy cases, namely, the Civil Code (Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch or “BGB”), the Code of Civil Procedure (Zivilprozessordnuung or “ZPO”), The Commercial Code (Handelsgesetzbuch or “HGB”), the Stock Corporation Act (Aktiengesetz or “AKtG”), AND THE Limited Liability Company Act (Gesetz betreffend die Gesellschaften mit beschränkter Haftung or “GMbHG”). See Braun, Ebrhard & Tashiro, Annerose, Germany, THE LAW OF INTERNATIONAL INSOLVENCIES AND DEBT RESTRUCTURINGS, 162 (Silkenat, James R. & Schmerler, Charles D., ed., Oxford University Press, 2006).

It should be noticed that, under the German bankruptcy law, liquidation and reorganization are two alternatives of a single bankruptcy procedure, but the rules on the treatment of executory contracts are applicable to both liquidation and reorganization cases.

The German Insolvency Code refers to “bankruptcy ” as “insolvency procedure” (Insolvenzverfahren).

Id.

See InsO §27; Klaus Kamlah, The New German Insolvency Act: Insolverzordnung, 70 Am. Bankr. L. J. 417, 426 (1996).

See InsO §§5, 10 and 20; Axel Flessner, supra note 37, at 322. A receiver (vorläufiger Insolvenzverwalter) may be appointed by the bankruptcy court with the purpose of supervising the debtor's operation; in some cases, the receiver replaces the debtor in the administration of the firm. See InsO §21. If the receiver is appointed by the bankruptcy court, the receiver has to prepare the report for the bankruptcy court on the financial condition of the debtor. See InsO §22.

Under the German bankruptcy law, the grounds for the commencement of a bankruptcy case is the debtor's insolvency as defined by sections 17, 18 and 19 of the German Insolvency Code. See 2-23 COLLIER INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS INSOLVENCY GUIDE [hereinafter Collier Int’l. Bus. Insol. Guide] ¶23.04[4] (2004).

A stay may be imposed by the bankruptcy court as a prejudgment measure; thus, unlike the American model, the stay is not triggered at the time when the bankruptcy petition is filed but until the bankruptcy relief is ordered. See InsO §§21-25, 88, 89; Axel Flessner, supra note 37, at 315.

See Eberhard Braun, Insolvenzordnung (INSO) Kommentar, 535 (Munchen, 2002).

Section 103 of the German Insolvency Code defines “executory contracts” as those bilateral contracts that are unperformed (completely or partially) by both the debtor and the non-debtor party at the time of the commencement of the bankruptcy case. See InsO §89.

Under the German Insolvency Code, the “bankruptcy trustee” is called “insolvency administrator” (Insolvenzverwalter), who is the individual that administers the bankruptcy estate. Id., §56. The court may allow the debtor to manage the bankruptcy estate with similar powers of those of the insolvency administrator under the supervision of a custodian (Sachwalter) on the request of the debtor at the time of the opening of the procedure. The court determines whether a trustee should be appointed or whether “self-administration” (Eigenverwaltung) should be allowed, but the creditor's assembly has the right to require the court to allow or prohibit the debtor from managing the bankruptcy estate, then it has the same powers of the trustee except for some acts such as the avoiding powers, which are exercised exclusively by the custodian. Id., §280.

Id., §103.

In plain terms, the bankruptcy estate is another name for the debtor when it is in bankruptcy.

Id., §35. The debtor's liabilities become claims against the bankruptcy estate.

Because a stay imposed on creditors and the debtor's ability to dispose of its assets is restrained on the commencement of the bankruptcy case, the effects are suspended until the bankruptcy trustee decides to perform or reject it. In fact, according to the German Insolvency Code, assumption consists in the bankruptcy trustee's action to request performance from the non-debtor party. Id., §103; Braun, supra note 45, at 528.

However, there are cases in which the German Insolvency Code expressly limits the bankruptcy trustee's power to reject executory contracts. Specifically, there are two types of contracts that cannot be rejected by the bankruptcy trustee: a) those contracts in which value is closely related to the identity of the person who originally contracted with the debtor (nonassignable contracts under ordinary non-bankruptcy laws); and b) contracts in which there is a property right that has already been acquired by the non-debtor party (conditional sales, and contracts that consist in transferring the property rights in real estate). In the first case, that is contracts that are not assignable to third parties under ordinary non-bankruptcy, the German Insolvency Code explicitly provides that such contracts are rendered terminated once the bankruptcy case has commenced, for example, agreement trading of financial futures and agency contracts. See InsO §§104, 115-117. In the second case, that is, contracts in which the non-debtor part has acquired a property right by virtue of the contract, the German Insolvency Code explicitly prohibits termination of those contracts, for example, conditional sales, only when the debtor is the seller and has delivered goods before the commencement of the bankruptcy case; otherwise, if the debtor is the buyer, the trustee can exercise its power to assume or reject the contract, Id. §107; real estate leases, only when the debtor is the lessor; otherwise, if the debtor is the lessee, the trustee can exercise its power to assume or reject the contract, Id. §§ 108 and 109; and any contract, regardless of how it is labeled, in which property rights on real estate property have been transferred under non-bankruptcy ordinary laws, Id. §106.

The German Insolvency Code refers to “administrative expenses” as “estate liabilities” (Masseverbindlichkeiten) See InsO §53.

Unlike the American system, under the German Insolvency Code it is not necessary to cure prepetition defaults in order to “assume” an executory contract. Prepetition default of the debtor remains as a debtor's prepetition liability; thus, any prepetition default of the debtor is treated as a general unsecured claim. This treatment has a procedural explanation. The commencement of the bankruptcy procedure turns prepetition liabilities into claims against the bankruptcy estate; under the German bankruptcy law, curing prepetition defaults would violate equal treatment among creditors. Id., §105.

Id., §§38, 47, 49-51 and 53.

Moreover, obligations related to performance of the contract have to be paid immediately as they come due; however, if the bankruptcy estate breaches the contract post assumption, the non-debtor party is entitled to damages compensation but has to wait until the confirmation of the reorganization plan to be paid. Id., §§53, 54, 55 and 90.

Id., §103.

This rule can be illustrated with the same numerical example provided in the subsection that explains rejection under the American model.

Id., §103.

The bankruptcy court does not have authority to compel the bankruptcy trustee to accelerate the disposition of executory contracts before the confirmation of the reorganization plan. Id.

The German Insolvency Code states that if the trustee fails to assume or reject within such period, it is deemed that the trustee has given up assumption of the contract and cannot require the counterparty to perform. Id.