Remdesivir and Nirmatrelvir-ritonavir (NTV/r) are the antiviral drugs available in Spain to prevent progression of mild-moderate COVID-19 in vulnerable populations. The pivotal clinical trials of both were conducted under different epidemiological conditions than the current ones. Therefore, their effect in the current setting is uncertain.

Patients and methodsA retrospective, multicentre, observational cohort study was conducted in 16 Spanish hospital emergency departments (ED). Data were collected from all patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 who presented to an ED in the first seven days after symptom onset between 1st January and 31st August 2022. The incidence of hospitalisation or death from any cause at 30 days (composite endpoint) after discharge from the ED was assessed, as was the occurrence of serious adverse drug reactions (ADRs). Data were analysed using Cox multiple regression and standardised survival curves.

ResultsA total of 2533 patients were included. The use of NTV/r was associated with a reduced risk of the combined endpoint compared to standard of care (SOC): adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) 0,528, 97,5% confidence interval (97,5%CI) 0,330 – 0,845; number of patients to treat to avoid an event, 24 (97,5%CI 13 – 283). No difference was detected between Remdesivir and SOC: aHR 0,835, 97,5%CI 0,524 – 1,394. No serious ADRs were identified.

ConclusionEarly use of NTV/r was associated with less risk of progression of mild to moderate COVID-19 in vulnerable patients, while no differences were found between Remdesivir and SOC. Their use was safe.

Remdesivir y Nirmatrelvir-ritonavir (NTV/r) son los fármacos antivirales disponibles en España para evitar la progresión de la COVID-19 leve-moderada en población vulnerable. Los ensayos clínicos pivotales de ambos se realizaron en unas condiciones epidemiológicas diferentes a las actuales. Por tanto, su efecto en el escenario actual es incierto.

Pacientes y métodosSe realizó un estudio observacional multicéntrico retrospectivo de cohortes en 16 Servicios de Urgencia Hospitalaria (SUH) españoles. Se recogieron los datos de todos los pacientes con COVID-19 leve-moderada que consultaron en un SUH durante los siete primeros días de clínica del 1 de enero al 31 de agosto de 2022. Se evaluó la incidencia de ingreso o muerte por cualquier causa a 30 días (evento combinado) tras el alta del SUH, así como la aparición de reacciones adversas a medicamentos (RAMs) graves. Los datos se analizaron mediante regresión múltiple de Cox y curvas de supervivencia estandarizadas.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 2533 pacientes. El uso de NTV/r se asoció con una disminución del riesgo de evento combinado respecto a cuidados habituales (SOC): hazard ratio ajustado (HRa) 0,528, intervalo de confianza al 97,5% (IC97,5%) 0,330 – 0,845; número de pacientes a tratar para evitar un evento, 24 (IC97,5% 13 – 283). No se detectó diferencia entre Remdesivir y SOC: HRa 0,835, IC97.5% 0,524 – 1,394. No se detectó ninguna RAM grave.

ConclusiónEl uso precoz de NTV/r se asoció con una menor progresión de la COVID-19 leve-moderada en población vulnerable, mientras que no se encontraron diferencias entre Remdesivir y SOC. Su uso fue seguro.

In the current context, COVID-19 is generally a mild illness, with patients typically presenting with flu-like symptoms. However, individual risk factors may lead to disease progression into more severe forms, potentially resulting in hospital admission and affecting patient survival.1,2 Since the disease was first identified, several clinical trials have been conducted in unvaccinated populations, demonstrating the efficacy of various molecules—administered early in the course of illness—in preventing progression among patients with risk factors. In these trials, the predominant viral variants were Alpha and Delta.3–6 These treatments have been available in Spain since late 2021, with their use initially prioritised for highly vulnerable patients according to recommendations issued by the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS). These recommendations were progressively expanded as treatment availability increased.7,8

Both the characteristics of the population and the circulating variants have changed since those clinical trials were conducted. Currently, a large proportion of the Spanish population has acquired immunity to the virus, either through vaccination or previous infection.9,10 In addition, the circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants now belong to different Omicron lineages, which differ from those present during the pivotal trials of these treatments.11 As a result, monoclonal antibodies such as sotrovimab have lost neutralising efficacy against the currently circulating variants.12 Furthermore, the small-molecule antiviral molnupiravir did not demonstrate efficacy in preventing death or hospitalisation at 28 days in a recent clinical trial.13

Despite the decline in SARS-CoV-2–related morbidity and mortality following successive changes in viral variants and mass vaccination campaigns,14 it remains a dangerous pathogen for older adults,15 immunocompromised individuals, and patients with comorbidities (the vulnerable population16), with a mortality rate twice that attributed to influenza.17–19 For this reason, effective treatments are still needed to halt disease progression and prevent the decompensation of underlying chronic conditions.20

Finally, the effectiveness of remdesivir and nirmatrelvir-ritonavir (NTV/r) in preventing the progression of mild to moderate COVID-19 in the Spanish population under current conditions remains unknown.

The primary objective of the present study is to assess the effect of remdesivir and NTV/r, each compared with standard care, on 30-day all-cause hospital admission or mortality in vulnerable patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 who present to a hospital emergency department (ED) in Spain. Secondary objectives include evaluating this effect in patients aged over 65 years, over 80 years, immunocompromised individuals, and those who presented within the first three or five days of symptom onset, as well as identifying serious adverse events associated with antiviral treatment.

Material and methodsDesign and patientsA retrospective multicentre cohort study was conducted in 16 Spanish hospital emergency departments (EDs) (Appendix B, Table S1 of the Supplementary Material). The study design was informed by the theoretical framework of target trial emulation proposed by Hernán et al. (Table 1), which is particularly useful when the implementation of a theoretical randomised clinical trial is not feasible due to resource limitations or ethical concerns, and evidence must instead be drawn from observational data, as is the case in the present study.21,22 The medical records of patients aged 18 years and older with a positive screening test for acute infection (antigenic test or polymerase chain reaction [PCR]) seen in participating EDs from 1 January to 31 August 2022 were examined. Patients with symptomatic mild-moderate COVID-19 (i.e. no need for supplemental oxygen), emergency physician's decision for outpatient management and who were candidates for antiviral treatment according to the fifth AEMPS recommendations, published on 2 August 2022 (available in the supplementary material) were included.7 Repeated records were excluded, as well as patients who had experienced symptoms for more than 7 days at the time of evaluation in the ED, those presenting with severe COVID-19 at onset, those with a hospital admission decision made for another reason during the index visit, those in whom treatment with an antiviral other than remdesivir or NTV/r was initiated, those with an ED stay of more than 24 h, those without symptoms attributable to SARS-CoV-2 infection, or those already receiving ongoing antiviral treatment prior to their ED visit.

Specification of the target clinical trial and its emulation in the present study.

| Target trial | Emulation | |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria | Microbiological diagnosis of COVID-19 (PCR or antigenic test positive for SARS-CoV-2) between 1 January and 31 August 2022. Visit to an ED, with an ED stay of less than 24 h. Mild-moderate symptomatic COVID-19 (no need for supplemental oxygen). Symptom duration less than 7 days. Risk factors for progression, according to the fifth recommendations of the AEMPS. No hospital admission criteria for other reasons. Clinical discharge decision. No ongoing antiviral treatment. | The same as in the target trial, plus availability of baseline variables in the medical records: sex, age, date and hospital of care, presence of immunosuppression, dialysis, Charlson index, overweight, hypertension, tobacco use, hospital admission in the previous 6 months, symptom onset timing, microbiological test performed, and recorded serious adverse events. Patients who started treatment with an antiviral other than remdesivir or NTV/r were also excluded. |

| Treatment strategies | Standard of care without antiviral treatment. Remdesivir. Nirmatrelvir-ritonavir (only if symptom duration is 5 days or less). | Same as target trial. |

| Allocation strategy | Random allocation to each treatment strategy, open-label. | Individuals are classified for each treatment strategy according to their observed data. Non-random allocation. |

| Follow-up | The timing of randomisation, treatment assignment, and discharge from the ED occur simultaneously. It starts at the time of discharge from ED and ends (whichever is earlier): - With the admission or death of the patient. - At 30 days of patient follow-up (administrative censoring). - Loss to follow-up (last contact with the healthcare system). | Same as target trial. |

| Outcome variable | Admission or death from any cause. | Same as target trial. |

| Causal contrast | Intention-to-treat effect. | Observational analogue of the intention-to-treat effect. |

| Analysis plan | Intention-to-treat analysis: Kaplan-Meier estimator was used to construct survival curves, with comparisons made using the log-rank test, and univariable semiparametric Cox regression employed to estimate the hazard ratio. Monitoring for the occurrence of serious adverse events. | Observational equivalent to intention-to-treat analysis: Estimation by standardisation of the survival function and multivariable semiparametric Cox regression to estimate the adjusted hazard ratio, both adjusted for baseline covariates that influenced the observed treatment assignment. Monitoring for the occurrence of serious adverse events. |

AEMPS: Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices; ED: hospital emergency department; NTV/r: nirmatrelvir-ritonavir; PCR: polymerase chain reaction.

This study followed the recommendations of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) initiative,23 with the corresponding checklist available in Appendix B, Table S2 of the Supplementary Material. Ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki were respected, and the study received favourable approval from the Research Ethics Committee (CEIM) of Hospital Clínico San Carlos under reference code 22/588-O_M_NoSP. Additionally, the study was registered in the Spanish Clinical Studies Registry under the code 0108-2022-OBS.

Primary outcomeThe primary outcome was defined as the composite event of all-cause death or hospital admission within 30 days. Patient follow-up began at the time of discharge from the emergency department, and the occurrence of the composite event was monitored through a review of the patient's medical records, including both hospital and primary care documentation.

Other variablesDemographic variables (sex, age, date and hospital of care), clinical variables (immunosuppression as defined by the AEMPS,7 use of chronic renal replacement therapy, Charlson comorbidity index, overweight, hypertension, tobacco use, hospital admission in the previous six months, date of symptom onset attributable to SARS-CoV-2 infection, and time of arrival and discharge from the ED), microbiological data (diagnostic method and viral variant identified, if sequencing was performed), vaccination status, treatment received (standard care without antiviral, remdesivir, or NTV/r), and history of previous COVID-19 infection were all collected. In addition, the occurrence of any serious adverse reaction attributable to antiviral treatment was documented. A serious adverse reaction was defined as one resulting in death or life-threatening condition, requiring hospital admission or prolongation of hospital stay, causing disability, or resulting in a foetal anomaly. All data were collected by investigators from each participating hospital using the patients’ medical records and entered into an electronic form developed with REDCap,24 covering the period from 1 January 2023 to 30 April 2024.

Sample sizeThe sample size was calculated based on the hazard ratio (HR) for the occurrence of the combined event, based on the results published by Arbel R et al.25 In this study, a 30-day cumulative incidence of 0.44% was observed in the antiviral arm and 1.90% in the standard of care (SOC) arm, which resulted in an unadjusted HR of 0.23. With a type I error rate of 5%, an adjustment for multiplicity was applied due to the planned analysis comparing each antiviral with standard of care (SOC), resulting in a 2.5% significance level for each comparison—i.e., remdesivir vs SOC and NTV/r vs SOC. Based on this, and assuming 80% power, the required sample size without losses was estimated at 1,043 patients per arm. Additionally, accounting for an anticipated 15% loss due to censoring or other reasons, the final estimated sample size needed per arm was 1,228 patients, for a total of 3,684 patients.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis of the sample was performed. Categorical variables were analysed using absolute and relative frequencies (percentages), and their distributions across the different treatment arms were compared using the Chi-squared test. Continuous variables were summarised using the median and the first and third quartiles, and comparisons among the three groups were conducted using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test. For time-to-event variables, event incidence between treatment arms was compared using the non-parametric log-rank test.

A Cox proportional hazards regression model was fitted for the composite outcome, with the main explanatory variable being the antiviral treatment received (remdesivir, NTV/r, or standard care only). Hazard ratios (HRs) with their corresponding confidence intervals were estimated, both unadjusted (univariable model) and adjusted (aHR) for potential confounding variables: sex, age, immunosuppression, hospital admission in the previous 6 months, Charlson comorbidity index, dialysis, hypertension, overweight, vaccination status, history of previous COVID-19 infection, and the day of symptom onset at which the patient was seen. Continuous variables were not categorised. In the multivariable model, patient clustering by hospital was accounted for using a frailty model to address this potential source of heterogeneity. Additionally, using the same confounding covariates, the standardized cumulative incidence difference between the antivirals and standard care without antivirals was estimated using the statistical package stdReg, also considering patient clustering by hospital as a cluster variable. In both analyses (Cox regression and standardization), to prevent underestimation of the standard error due to dependence among observations from the same hospital, variance estimation was performed using robust sandwich-type estimators.26,27 If a 30-day standardized incidence difference was observed with a confidence interval excluding zero, the number needed to treat (NNT) or number needed to harm (NNH) was calculated, defined as the inverse of the cumulative incidence difference at the end of follow-up.28 These calculations were performed for the entire sample, for patients over 65 and 80 years of age, for immunocompromised patients, and according to symptom duration (less than 3 and 5 days).

Additionally, the potential impact of informative censoring was assessed by estimating the adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) and the 30-day standardized cumulative incidence for the primary outcome in two simulated samples without censoring: one assuming that patients lost to follow-up did not experience the event by the end of the 30-day follow-up period (best-case scenario), and the other assuming that all censored patients experienced the event at the time of censoring (worst-case scenario).26

The type I error rate was set at 0.05, and all tests were two-sided. Due to the multiplicity adjustment applied only to the primary outcome (full cohort), estimates for this outcome were accompanied by 97.5% confidence intervals (CI 97.5%). For all other secondary analyses, 95% confidence intervals (CI 95%) were reported. The analyses were performed using R version 4.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

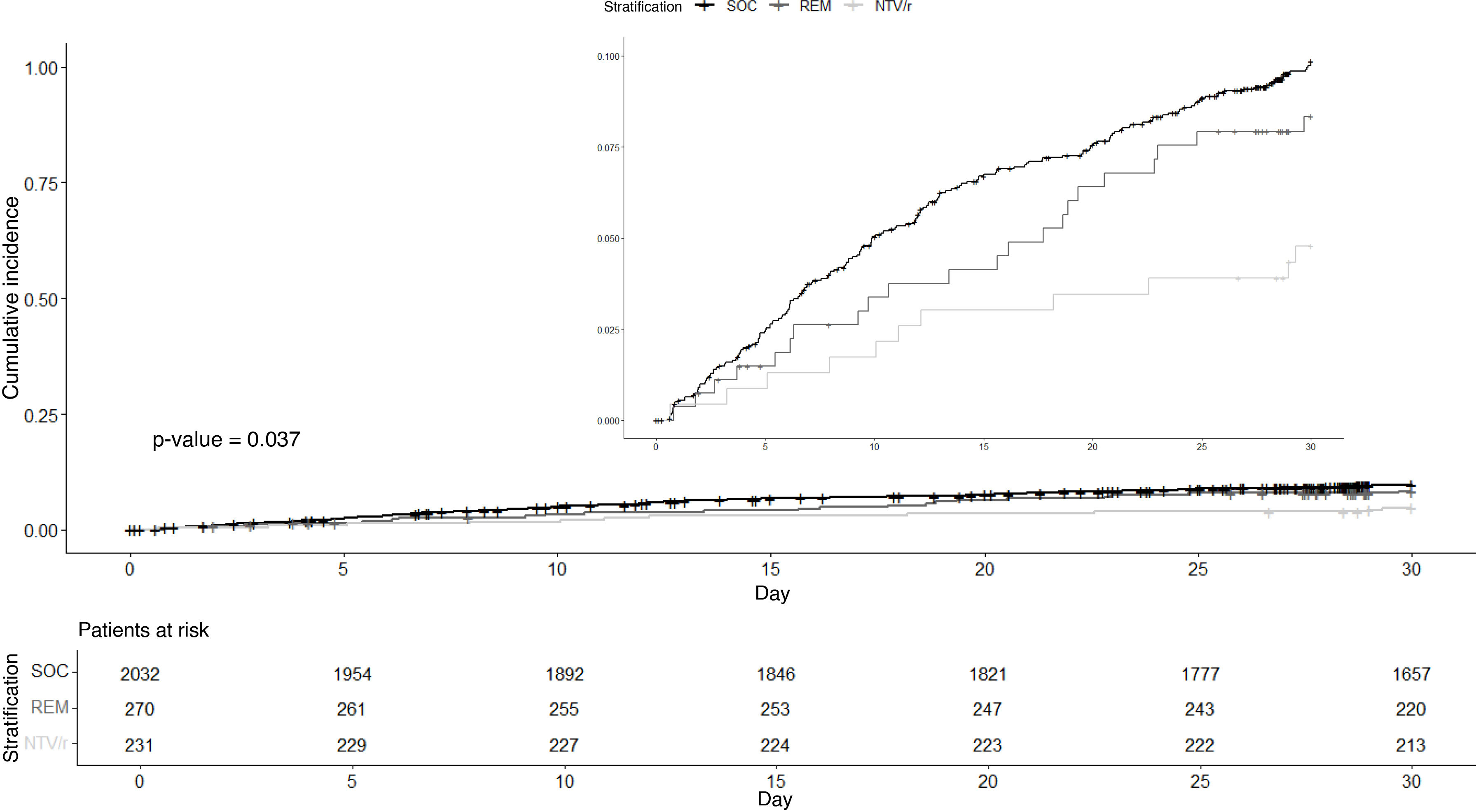

ResultsSample descriptionFig. 1 shows the inclusion flowchart of the study. A total of 36,729 records were examined and 2,533 patients were eventually included. Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of patients in each treatment arm (usual care without antiviral, remdesivir or NTV/r). A higher proportion of immunosuppressed patients were found in those who received antivirals, while those who did not receive antivirals were older. There was a lower representation of patients on dialysis and those who were overweight among those receiving NTV/r, while this group had a higher proportion of episodes classified as reinfections. The cohort was widely vaccinated, with over 80% of patients in all treatment arms having completed full vaccination (three or more doses). Fig. 2 shows the crude cumulative incidence curves for each treatment arm, along with the number of patients at risk at each time point during follow-up. The overall median follow-up was 30 days (first and third quartiles, 30–30). Follow-up was incomplete for 216 patients (8.5%), with the NTV/r arm experiencing less censoring than the others. The event of interest occurred in 228 patients (9.0%), of whom 23 (0.9%) died and 205 (8.1%) were hospitalised. Microbiological diagnosis was made by PCR in 978 cases (38.6%), with sequencing performed in 279 of these (28.5% of PCR-positive patients). The Delta variant was identified in 26 patients (2.7% of PCR-positive patients), while the remaining sequenced samples corresponded to various Omicron variants. There were no missing data for baseline covariates.

Baseline sample characteristics.

| No antiviral (n = 2.032) | Remdesivir (n = 270) | NTV/r (n = 231) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 1,022 (50.3%) | 154 (57.0%) | 128 (55.4%) | 0.052 |

| Dialysis | 93 (4.6%) | 25 (9.3%) | 4 (1.7%) | <0.001 |

| Immunosuppression | 435 (21.4%) | 145 (53.7%) | 175 (75.8%) | <0.001 |

| Prior COVID-19 | 149 (7.3%) | 17 (6.3%) | 28 (12.1%) | 0.023 |

| Hospitalisation in the last 6 months | 282 (13.9%) | 45 (16.7%) | 40 (17.3%) | 0.208 |

| Overweight | 360 (17.7%) | 34 (12.6%) | 22 (9.5%) | 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1,416 (69.7%) | 170 (63.0%) | 86 (37.2%) | < 0.001 |

| Age§ | 78.33 (69.86. 85.71) | 69.93 (58.66. 80.06) | 64.24 (51.56. 77.92) | < 0.001 |

| Charlson index§ | 2.00 (1.00. 3.00) | 2.00 (1.00. 4.00) | 2.00 (1.00. 3.00) | 0.048 |

| Day of symptoms on arrival at the ED§ | 2.05 (1.00. 3.35) | 2.05 (1.00. 3.14) | 2.00 (1.05. 3.00) | 0.407 |

| Unvaccinated | 136 (6.7%) | 17 (6.3%) | 13 (5.6%) | 0.128 |

| Vaccinated with 2 doses | 203 (10.0%) | 23 (8.5%) | 21 (9.1%) | |

| Vaccinated with 3 doses | 1,361 (67.0%) | 166 (61.5%) | 159 (68.8%) | |

| Vaccinated with 4 doses | 332 (16.3%) | 64 (23.7%) | 38 (16.5%) | |

| Never smoker | 856 (42.1%) | 107 (39.6%) | 90 (39.0%) | 0.042 |

| Active smoker | 143 (7.0%) | 26 (9.6%) | 19 (8.2%) | |

| Ex-smoker | 554 (27.3%) | 76 (28.1%) | 48 (20.8%) | |

| Smoking status unknown | 479 (23.6%) | 61 (22.6%) | 74 (32.0%) |

Categorical variables are expressed as absolute frequency and relative frequency (in parentheses), with p-values calculated using the Chi-square test. Quantitative variables (§) are expressed as median and interquartile range (in parentheses), with p-values calculated using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test.

NTV/r: nirmatrelvir-ritonavir.

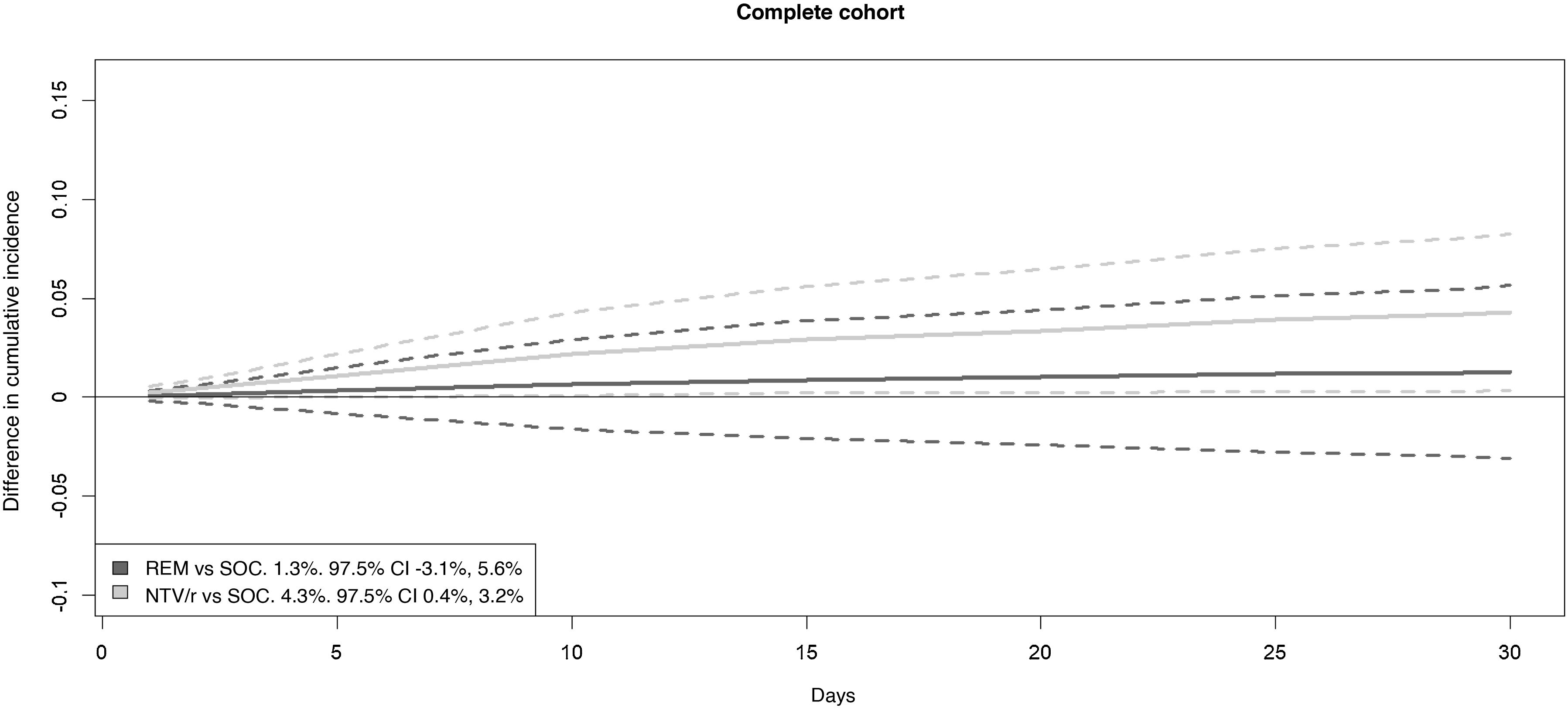

Table 3 and Fig. 3 show the results for the full cohort analysis. An adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) of 0.528 (97.5% CI: 0.330–0.845) was observed for treatment with NTV/r compared to standard of care (SOC). This protective effect corresponded to a standardized cumulative incidence difference of the composite event at 30 days of 4.3% (97.5% CI: 0.4–8.3%) in favour of NTV/r versus SOC. The null hypothesis of no difference in effect between remdesivir and SOC could not be rejected: aHR 0.855 (97.5% CI: 0.524–1.394), with a standardized cumulative incidence difference of 1.9% (97.5% CI: −0.3–5.6%).

Results of the estimated Cox regression models.

| Patients | Events | Remdesivir vs. SOC | Nirmatrelvir-ritonavir vs. SOC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude HR (CI) | Adjusted HR (CI) | Crude HR (CI) | Adjusted HR (CI) | |||

| Full cohort | 2,533 | 228 | 0.835 (0.505−1.383) | 0.855 (0.524−1.394) | 0.470 (0.235−0.942) | 0.528 (0.330−0.845) |

| Over 65 | 1,998 | 199 | 1.139 (0.709−1.829) | 0.980 (0.646−1.487) | 0.508 (0.225−1.146) | 0.490 (0.279−0.863) |

| Over 80 | 1,013 | 113 | 0.726 (0.319−1.652) | 0.669 (0.302−1.481) | 0.328 (0.081−1.327) | 0.343 (0.138−0.852) |

| Immunocompromised patients | 755 | 68 | 0.673 (0.349−1.300) | 0.806 (0.318−2.041) | 0.498 (0.252−0.960) | 0.629 (0.394−1.004) |

| Symptom duration less than 5 days | 2,290 | 201 | 0.839 (0.528−1.334) | 0.833 (0.526−1.318) | 0.499 (0.271−0.918) | 0.570 (0.377−0.859) |

| Symptom duration less than 3 days | 1,719 | 148 | 0.696 (0.394−1.232) | 0.747 (0.377−1.480) | 0.345 (0.152−0.782) | 0.452 (0.206−0.878) |

The confidence interval (CI) is given at 97.5% for the full cohort, and 95% for the rest of the analyses. Each drug is compared to standard of care (SOC), without antiviral.

HR: hazard ratio; vs: versus.

Standardized cumulative incidence difference curves for the drugs compared with standard care. The legend shows, alongside each comparison, the reduction in standardized cumulative incidence at 30 days with its 97.5% confidence interval. The greater the positive difference, the larger the magnitude of the protective effect. NTV/r: nirmatrelvir/ritonavir; REM: remdesivir. Solid lines: point estimate. Dashed lines: 97.5% confidence interval.

Table 3 and Supplementary Figures S1 and S2 (Appendix B) present the results of the additional analyses performed. Treatment with NTV/r was associated with adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) ranging from 0.343 to 0.570 depending on the subgroup studied, except in immunocompromised patients, where the point estimate of the protective effect (aHR: 0.629) did not allow rejection of the null hypothesis of no difference compared to standard of care (SOC) (95% CI: 0.394–1.004). None of the secondary analyses involving remdesivir showed a significant association or detected differences compared to SOC.

Number needed to treatAppendix B Figures 3, S1 and S2 in the supplementary material show the standardised cumulative incidence difference curves for each of the drugs compared to the standard of care. This difference included zero for remdesivir, but a strictly positive confidence interval was observed for NTV/r in the full cohort, in patients over 65 years of age, and in those who presented within 3 and 5 days of symptom onset. Partial overlap of the confidence intervals for both drugs is also evident. The number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one hospital admission or death from any cause within 30 days with NTV/r in the target population was 24 patients (97.5% CI: 13–283). In secondary analyses for NTV/r, the NNT was 20 (95% CI: 11–182) for patients over 65 years, 27 (95% CI: 14–538) for patients with fewer than 5 days of symptoms, and 20 (95% CI: 10–741) for patients with fewer than 3 days of symptoms. For other NTV/r subgroups, the confidence interval for the standardized cumulative incidence difference included zero.

Sensitivity analysisIn the most optimistic scenario (best-case scenario), in which all patients lost to follow-up before 30 days were assumed not to have experienced the composite event by the end of follow-up, the adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) was 0.854 (97.5% CI: 0.526–1.386) for remdesivir and 0.533 (97.5% CI: 0.331–0.858) for NTV/r. The 30-day cumulative incidence difference for remdesivir compared to standard of care (SOC) was 1.3% (97.5% CI: −3.0–5.5%), and for NTV/r it was 4.2% (97.5% CI: 0.3–8.0%).

In the most pessimistic scenario (worst-case scenario), in which all censored patients were assumed to experience the composite event at the time of loss to follow-up, the adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) was 0.988 (97.5% CI: 0.578–1.689) for remdesivir and 0.439 (97.5% CI: 0.288–0.670) for NTV/r. The 30-day cumulative incidence difference for remdesivir compared to standard of care (SOC) was 0.2% (97.5% CI: −8.7–9.1%), and for NTV/r it was 9.8% (97.5% CI: 0.9–18.6%).

Serious adverse events attributed to antiviralsNo serious adverse events attributable to the antivirals were reported.

DiscussionIn patients at risk of disease progression due to underlying risk factors, early treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 with NTV/r was associated with a reduced risk of hospitalisation or all-cause mortality at 30 days. This association was observed in some subgroup analyses, although these comparisons were limited by reduced sample sizes. The protective effect is robust, as it was adjusted for potential confounders through multivariable regression and standardisation, and the hospital factor was also considered as a possible source of heterogeneity in the effect. These findings have been replicated in other geographic locations,25,29 showing a protective association against hospitalisation and death similar to that observed in this study.

In the case of remdesivir, although the point estimates suggest a protective effect, their confidence intervals included one in the multivariable Cox regression and zero in the standardized incidence difference, meaning the null hypothesis of no difference between remdesivir and standard of care (SOC) cannot be rejected. The observed difference in effect between the two antivirals compared to standard care without antivirals should not be interpreted as evidence of superiority of one antiviral over the other, as the study design does not allow for a direct comparison, and moreover, the confidence intervals of both antivirals’ estimates overlap. Additionally, a larger study conducted in the United States involving hospitalised adults not requiring supplemental oxygen (11,637 patients, nearly 46 times larger than our study) found a protective association of remdesivir against 28-day mortality (adjusted HR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.76–0.90).30 Another study in Mexico involving immunocompromised patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 also reported a protective association against hospitalisation and death at 28 days (adjusted HR: 0.16; 95% CI: 0.06–0.44).31 The discrepancy between our findings and those previous publications may be related to the sample size of our study, which did not reach the initial planned target.

Regarding safety, no serious adverse events were detected. To the best of our knowledge, this effectiveness and safety data represent a novel contribution to the clinical outcomes of antiviral treatment for mild to moderate COVID-19 in the Spanish population at risk of disease progression presenting to hospital EDs.

Our study has several strengths. Firstly, the conditions under which the drugs were administered during the recruitment period closely resemble those currently in place, both in terms of antiviral prescription criteria and clinical-virological characteristics. The population studied exhibits a high degree of immunity from previous infections and vaccination, and the circulating variants show similar virulence, all belonging to different Omicron sublineages.8,11,20 Therefore, it is expected that the results found will remain valid in the current context. Secondly, accounting for potential heterogeneity among patients due to their care being provided at different hospitals enhances the generalisability of the results across Spain.26 Thirdly, the effect estimation is not limited to a relative risk measure (adjusted hazard ratio, aHR), but also includes an absolute measure expressed as the difference in cumulative incidence and the number needed to treat (NNT). This absolute measure provides a more comprehensive understanding of the effect size.27,28 Moreover, sensitivity analyses addressing the potential impact of informative censoring ruled out such bias, as they yielded estimates similar in direction and magnitude to those observed in the main analysis.26 Finally, the use of the target trial emulation framework offers robust support by refining the effect magnitude and approximating a causal estimate.21,22

The main limitation of this study is that the rate of antiviral prescription in Spanish hospital emergency departments (EDs) was lower than expected, and the required sample size for the antiviral treatment arms was not reached. This was partially compensated by a larger number of patients without antiviral treatment. This limitation reduces the statistical power to detect a potential true effect of the interventions26. Moreover, the retrospective nature of the study makes it more vulnerable to missing information that was not recorded in the medical records. This was mitigated through rigorous review of patient records and thorough data cleaning by the research teams at each hospital. As a result, there were no missing data in the database. Although no serious adverse events attributable to antivirals were recorded, mild adverse events—such as dysgeusia, a common mild and transient side effect of NTV/r6—cannot be ruled out as they may have gone unnoticed. Finally, despite considerable efforts to control for confounding and attempt to infer causality, causal relationships can never be fully assured in an observational study, as unmeasured confounders or residual confounding may still be present.21 This inherent limitation, common to all observational studies, increases uncertainty and may affect point estimates.32 Nonetheless, in this study, consistent conclusions were reached using two different adjustment methods—multivariable regression and standardisation—supporting the robustness of the findings.

New studies with an adequate sample size are needed in the Spanish population to investigate the effect of remdesivir in the current context, as well as the effectiveness of both antivirals in immunocompromised patients. Regarding this population, it is crucial to distinguish between different degrees and types of immunosuppression (humoral, cellular, etc.) in order to individualise and optimise treatment protocols.33

ConclusionsEarly treatment with NTV/r of mild-moderate COVID-19 in patients at risk of progression in Spanish EDs was associated with a reduced risk of hospitalisation and all-cause mortality at 30 days. No difference in effect was found for remdesivir compared to the standard of care (SOC), although the study’s statistical power was suboptimal due to not reaching the planned sample size. Both treatments demonstrated a high safety profile, as no serious adverse events were reported.

Ethical considerationsConducted in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). Approval was obtained from the CEIm (Comité Ético de Investigación con Medicamentos) of the Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos de Madrid, with code 22/588-O_M_NoSP. The study was also registered in the Spanish Clinical Trials Register under code 0108-2022-OBS. Participants were considered exempt from the request for informed consent.

FundingThis work has been partially funded by research grant PID2022-137050NB-I00. Ministry of Science and Innovation, Spain (TPP). This was an unconditional collaboration, and therefore did not influence the design, data collection, data analysis, drafting or revision of the manuscript.

The Foundation for Biomedical Research and Innovation of the Infanta Sofía University Hospital and Henares University Hospital (FIIB HUIS HHEN) funded the publication costs of this article.

CMRL has received honoraria for lectures and funding for conference attendance from Gilead and Pfizer. MSRG has received funding for conference attendance from Gilead. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this article.

We thank Miguel Ángel Luque Fernández for his valuable advice on the methodological approach.