In the digital service supply chain, digital service providers undertake the marketing platform development programs with satisfying digital service quality (DSQ) to help traditional retail enterprises (TREs) achieve digital technologies and merchandizing innovation. To illustrate the influence of external reference knowledge on principals’ feeling on DSQ and improvements, this study develops a novel framework to assess TREs’ perceived DSQ and design incentive strategies concerning differential cooperation scenarios. The study integrates the prospect theory and the principal-agent model to reveal the DSQ incentive strategies influenced by external references. Its contributions include (1) proposing DSQ appraisal indicator system and standardized computation process, (2) revealing the influence of external referencing knowledge on psychological utility in DSQ cooperation, and (3) exploring the incentive framework and equilibrium of DSQ utility in the differential degrees of information asymmetry. The managerial implications can assist the TREs in selecting digital marketing KPIs, determining proper benchmarks, confirming the dynamical dominance of external references, reducing the degree of information asymmetry, and implementing effective incentives.

In the digital economy era, the customers’ shopping habits and activities are dramatically changing to global e-commerce sales via mobile devices (Dolega et al., 2021). As an effective business-driven hand (Azemi et al., 2022), digital marketing platform can provide the professional functions (e.g., precise promotion, real-time interaction, and data security) (Kashyap et al., 2025), enhancing customers’ shopping experience and retailing brand reputation. In the trend of digital transformation, traditional retail enterprises (TREs) have an urgent demand for building the digital marketing platform to achieve marketing innovation, such as data mining (Royle & Laing, 2014), business operation (Reim et al., 2022), and sale prediction (De Caigny et al., 2020). Digital marketing technologies have become the driving force in realizing effective precision marketing (Chou et al., 2022), exact market positioning (Palmié et al., 2022), potential customer recognition (Yang et al., 2021), and clear customer segmentation (Kalia et al., 2022). Regarding platform competitiveness, digital service quality (DSQ) presents the customers’ comprehensive satisfaction with the digital marketing technologies and is required to determine the assessment criteria and standardization measurement.

In the development process of digital marketing platform, TREs always cooperate with digital service providers (DSPs) to conduct joint development. As the agent, DSPs guarantee the digital platform with a certain DSQ (Anand & Goyal, 2019). The DSQ can describe the effect of joint development. More importantly, the TRE’s perspective on DSQ is significantly influenced by external reference points, such as the main competitor’s DSQ and industrial DSQ. If the TRE’s received DSQ is better than an external reference level, it will gain additional positive psychological benefits caused by the leading position. If the TRE’s received DSQ is lower than an external reference level, it will experience additional negative psychological effects because of the lagging DSQ. The influence of external reference knowledge on the TRE’s perceived DSQ should be explored to show its psychological utility. Particularly in the situation of many references, the varying weights of different benchmarks should be appropriately determined to describe the aggression effect.

In the digital supply-chain cooperation, the degree of information asymmetry determines the participant’s dominant position, which affects the DSQ incentive strategy selection. In digital cooperation, the TRE is the principle and asks the DSP to develop the digital marketing platform with competitive advantages. As the agent, the DSP, first, always devises the initial decision-making on development investment, which is often influenced by self-interest toward its own optimal strategy (Greenstone et al., 2022). Later, the TRE has to accept the DSP’s investment result and final digital platform with DSQ, which leads to an adverse selection consequence (Pavlov et al., 2022). Because of information asymmetry, moral hazard is generated and may be detrimental to the TRE’s interests (Zhang et al., 2023). Consequently, establishing an effective incentive mechanism is a crucial management solution for the above ethical dilemma (Liu et al., 2022). Although previous studies contributed to the direct transaction effect, the incentive focused on the independent improvement. According to the prospect theory, the TRE’s perspective on DSQ is highly reliant on external references. The incentive objective can be expanded to psychological utility.

To prevent the DSP’s moral hazard in the development cooperation, this study merges the prospect theory into a principal-agent model considering the TRE’s psychological utility regarding competition position and information asymmetry. The proposed cost-sharing incentive method can assist the TRE in achieving satisfied perceived DSQ in the digital service supply chain. As indicated in Figure 1, the steps of the study are indicated to highlight its general perspective.

The contributions of the research include the following

- (1)

The definition and a set of indicators of innovation-driven DSQ have been established, providing a foundational analytical framework for measuring digital marketing performance.

- (2)

How external reference points affect the TRE’s psychological utility is examined with a focus on optimistic preferences.

- (3)

The incentive solution under symmetric and asymmetric information situation is explored.

The contents of the study are organized as follows. Section 2 summarizes existing research and research gaps. Section 3 presents the theoretical framework of the research. In Section 4, the definition of DSQ and the perceived utility considering dual reference points are presented, and the perceived DSQ under a single reference point is given. In Section 5, the incentive mechanism is conducted through the “principal-agent” theory. In Section 6, the incentive solution is provided under symmetric and asymmetric information situations. In Section 7, a numerical study is conducted to prove the effectiveness of the above method. Section 8 provides the research conclusions and future research topics.

Literature reviewThe study considers the overlapping digital marketing domains, reference points, and incentive methods. Consequently, this section provides a brief overview of the following three aspects. The subsection describes the research gap for precisely assessing the TRE’s overall psychological utility and designing related incentive solutions.

The impact of digital technology on digital marketingIn the new retail era, emerging digital technologies are rapidly changing the marketing environment in the areas as consumer behavior (Ratchford et al., 2022), social media with user-generated content (Babić et al., 2020; Šola et al., 2022), digital marketing platforms (Veile et al., 2022) and online searching strategy (Lin et al., 2020; Agnihotri, 2020)). Ratchford et al. (2022) examined how digital technology affected consumers’ search costs and search behavior through online shopping, which revealed that the Internet shortened the customers’ consideration time. Babić et al. (2020) explored the generation process of consumers’ electronic word-of-mouth in social media related to associate monetary value. Veile et al. (2022) conducted an exploratory numerical study to analyze how digital platforms changed industrial firms’ business models and marketing strategies. Lin et al. (2020) revealed that paid search engines could promote users’ purchasing frequency and increase customers’ lifetime value by effectively identifying high-value customers. The above related research contributes to understanding the various digital marketing processes affected by technology and provides the support for identifying the relevant DSQ indicators that reflect the current digital marketing landscape.

The role of psychological utility and weighting methods in the supply chainPrior research in this domain provides a solid foundation for better understanding how reference knowledge impacts supply chain activities, providing a basis for incorporating psychological factors into the TRE’s economic benefit.

Psychological utility in supply-chain cooperation under reference pointsIn supply-chain cooperation, reference points significantly influence the participants’ psychological competitive utility, which is widely used in ordering decisions (Wei et al., 2019; Uppari & Hasija, 2019)), pricing strategies (Das et al., 2021), supply-chain coordinate tactics (Qiu et al., 2022; Vipin & Amit, 2021), risk control (Liu & Chen, 2019), supplier selection (Chai et al., 2023), and supply-chain performance evaluation (Liang et al., 2022). Wei et al. (2019) studied the impact of external industry level and minimum profit expectations on the newsboy decision problem. Das et al. (2021) proposed a manufacturer’s loss aversion model under the reference level to design a pricing strategy in a green supply chain. Qiu et al. (2022) addressed the coordination problem concerning dynamic reference points in online-offline channels with different structures. Liu and Chen (2019) introduced a profit reference point into the decision-makers’ psychological perception of risk. Chai et al. (2023) established a sustainable supplier selection decision framework in which positive and negative ideal reference points were considered to describe decision-makers’ risk preferences. Liang et al. (2022) considered decision-makers’ bounded rationality under random subjective reference points and constructed a supplier performance evaluation model in five dimensions.

The weighting method of psychological competitive utilities under multiple reference pointsTo consider the contributions of multiple reference points, the weights of different reference points should be suitably designed to aggregate the participants’ psychological competitive utilities. Existing weighting methods include subjective designation (Zhong et al., 2022; Liang et al., 2020), additive method (Wei et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020), and attitude evaluation (Zhu et al., 2017). Zhong et al. (2022) employed subjective equal weights to integrate psychological utility with monetary and time reference points. Wei et al. (2019) simply added the influence of the bottom line and the status quo reference point when measuring the psychological utility of newsboys. Zhu et al. (2017) treated decision-makers’ attitudes toward the reference points as the coefficient for determining the weights.

The incentive solutions in supply chain cooperationIn supply-chain cooperation, the research on incentive mainly focuses on the impact of incentives on supply-chain performance (Gao et al., 2023), incentive mechanism design (Chakraborty et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2022), and information management in incentive system (Li & Zhang, 2021; Fu & Xing, 2021). Gao et al. (2023) analyzed the response decisions of the supply chain under the incentive strategies, which revealed that incentives could enhance inventory carryover capability in decentralized supply chains. Chakraborty et al. (2019) addressed the cost-sharing mechanism between the retailer and the manufacturer, which intensified the value of a cost-sharing contract on improving supply-chain performance. Li and Zhang (2021) explored the influence of real-time information and the participants’ forecasting ability on the design of incentive mechanism in the supply chain, in which information acquisition could promote supply-chain members to distort optimal decisions. These studies on incentive solutions in supply-chain cooperation can provide a basic framework for us to design more effective incentive mechanisms that consider comprehensive psychological utility and external DSQ reference points in our research.

In summary, existing research has revealed various incentive methods for improving the participants’ economic benefits and mitigating the agents’ moral hazard. However, in the digital economy era, the principal’s psychological feeling on DSQ is significantly influenced by the external reference knowledge and future potential. The incentive focus should be extended from single economic benefit to comprehensive psychological utilities, considering the effect of external DSQ reference points and varying weights. First, the definition, criteria, and computation process of DSQ should be updated according to the feature of digital economy. Second, the TRE’s psychological utility regarding the DSQ needs to be reasonably measured to illustrate the influence of external benchmarks. More importantly, the exploration of psychological utility was not employed in the principal-agent framework. In digital service cooperation, the DSP prioritizes its own benefits because of information asymmetry, which may be detrimental to the TRE’s interests. The degree of information asymmetry can affect the equilibrium of the principal-agent analysis. Consequently, an incentive method, which reasonably evaluates the TRE’s psychological utility and considers the degree of information asymmetry, should be explored to directly support the service supplier’s management activities.

Theoretical frameworkThis paper selects the digital service supply chain to explore the incentive solution for improving DSQ with regard to dual external references and varying weights. Combining digital marketing (Ratchford et al., 2022), the prospect theory (Wei et al., 2019), and weighting (Zhong et al., 2022) and incentive methods (Liu et al., 2022), the theoretical framework is proposed in Figure 2. The logic of the study is developed as “Actual DSQ and perceived DSQ” → “Aggression for comprehensive DSQ with varying weight” → “principal-agent framework” → “Incentive solutions in specific scenarios” → “Managerial implications.” In particular, the novel requirements of digital marketing provide the guidance on designing the definition and potential indicators of DSQ, which is the answer to the first research question. Next, the prospect theory is used to transfer the DSQ to the TRE’s perceived DSQ, which considers external reference points and varying weights to demonstrate future potentials, as the exploration of the second research question. Furthermore, to fulfill the third research gap, the principal-agent model is established to describe the improvement requirement of the TRE’s perceived DSQ, and the incentive theory explains the cost-sharing incentive solutions to prevent the DSPs’ moral hazard caused by information asymmetry. The TRE can use the incentive solutions to design suitable supply-chain contract to solve the adverse selection problem.

Stage 1: Actual DSQ. Referring to the digital marketing requirements, first, DSQ is defined, and multiple indicators in the dimensions of digital tangibles, digital trust, digital interaction, customer centricity, and reliability are proposed as the KPIs (Büyüközkan et al., 2020). Second, the raw performance data, qi, as well as the expectations and tolerant intervals of KPIs, can be obtained. Next, the KPIs can be divided into the smaller-the-better, the larger-the-better, and the nominal-the-better, which provides a framework for standardizing and aggregating the DSQ (Taguchi, 1986). At the technology level, Artificial Intelligence (AI) can be utilized to determine appropriate DSQ indicators deconstructed from the TRE’s vision and mission. AI can handle a large amount of data and identify the key factors related to DSQ, which is in line with the insights into market and customer needs in the marketing theory. To avoid human operating error, Machine Learning (ML) could be employed in the data standardized process and ensure automated computation. A detailed calculation process is conducted in Section 4.1.

Stage 2: Comprehensive DSQ under dual reference knowledge. Guided by the prospect theory (Barberis, 2013), the TRE’s value function under a single reference knowledge is developed. Additionally, optimistic preference, ki, is proposed to reflect the TRE’s attitude on the future improvement potential of DSQ. Considering the fierce market competition (Llopis-Albert et al., 2021), the main competitor’s DSQ, rc, and industrial DSQ, rh, are selected as dual references points. Moreover, to calculate the TRE’s comprehensive perceived DSQ, the influence of optimistic preference and varying DSQ distances are integrated, which induces dynamic weight in the aggregation process. The prospect theory focuses on an individual’s reliance on reference points when making decisions and their different perceptions of gains and losses. In this stage, data mining can be applied to obtain unstructured knowledge (e.g., industry survey and competitor’s operation report) online, identifying “industrial-level” and “competitor-level” DSQ benchmarks. Through data mining, specific and quantifiable reference points are found, making the application of the prospect theory in DSQ evaluation more specific and operable, and achieving a deep integration of theory and cutting-edge technologies in a quantitative perception of DSQ. Section 4.2 presents the above specific operations.

Stage 3: Principal-agent framework and incentive mechanism. First, based on the comprehensive calculation of the TRE’s perceived DSQ, its psychological utility can be obtained, which concerns the influence of external reference points with economic benefits. Second, a principal-agent model containing incentive compatibility constraints and individual rationality constraint is proposed. Next, the incentive process of cost-sharing is designed to explore the optimal solution of the cooperation. In this stage, reinforcement learning can be applied to dynamically optimize incentive parameters (e.g., cost-sharing ratios) in the “principal-agent” model by analyzing real-time data on market conditions and psychological utility preferences. The trial-feedback-adjustment cycle can refine the related incentive strategies through iterative improvement and maintain robustness across differential scenarios containing risk preference shift or competitive intensification. This enables the “principal-agent” theory to adapt to the dynamically changing market environment in practical applications and transform the abstract incentive mechanism into specific strategies that can be adjusted and optimized in real time. The detailed operations are illustrated in Section 5.

Stage 4: Incentive solutions in specific scenarios. According to the degree of the DSP’s private information, the optimal solutions in different supply-chain dominant conditions are discussed. First, under the condition of complete symmetric information, the TRE has a dominant position in the supply-chain cooperation, which prioritizes achieving its expected psychological utility. Second, the cost-sharing incentive solution of the “principal-agent” model in the case of complete asymmetric information is analyzed. Next, under partly asymmetric information, the equilibrium of the transaction is explored where the participants are fighting for the dominance. The incentive theory is centered on devising efficient incentive mechanisms to drive agents toward fulfilling principals’ objectives. In this stage, the blockchain technology is harnessed to ensure the transparency of information flow by recording unalterable transaction data, which serve as a dependable basis for evaluating the level of information symmetry. Blockchain can be leveraged to ensure transparent information flow by recording immutable transaction data. Assessing the degree of information symmetry (e.g., symmetric, partially asymmetric) could enable tamper-proof validation on DSP performance and reduce moral hazard in incentive strategy design. The calculation process can be found in Section 6.

Stage 5: Managerial implications. After the empirical study, some policy implications, such as, the selection of DSQ KPIs, determination of competitive benchmarks, adoption of varying weights and designation of incentive solutions, are provided, which can directly help the TRE to enhance the DSQ and improve the operation performance.

In the following sections, the main terminologies and notations used in this paper are summarized in Table 1.

Variables and their meanings.

As shown in Figure 3, this section illustrates the definition of DSQ and its computation method in Section 4.1, which contains the indicators, standardization and aggregation. The perceived DSQ concerning a reference point and the optimistic preference are put forward in Section 4.2. The TRE’s comprehensive perceived DSQ under dual reference points is calculated with regard to the dynamic dominance of external reference points in Section 4.3.

Digital service quality and its computation methodDigital service quality and its indicatorsTraditional Service Quality (SQ) primarily describes the customers’ satisfaction with the service (Chen et al., 2022). In the SERVQUAL framework, SQ reflects the customers’ expectations and needs regarding the service trust in offline channels (Barakabitze et al., 2019), which can be measured with the following five dimensions: tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy (Parasuraman et al., 2002). Because of the rapid development of mobile Internet, electronic SQ (e-SQ) focuses on the customers’ interactive assessments on online SQ, primarily evaluating independent online service processes (e.g., web browsing and online transactions) through Internet technologies with metrics such as response time and usability (Chao et al., 2024). E-SQ can be measured in four dimensions as follows: efficiency, system availability, fulfillment, and privacy (Chao et al., 2024). In the new retailing era, the integration of online service is emerging, and digital marketing platform can provide systematic digital solutions covering the overall marketing life cycle, which not only focuses on technological implementation (such as platform stability) but also emphasizes the deep integration of technology and business. For example, AI-driven precision marketing push directly improves the marketing return on investment (ROI) in retail enterprises, rather than merely optimizing online interactive experiences. DSQ represents a holistic evaluation of end-to-end digital solutions in the new retail era, extending to the entire marketing life cycle from real-time data collection and AI-driven personalization to customer engagement in innovation. The evolution of SQ, e-SQ, and DSQ is illustrated in Figure 4.

To realize digital transformation from separated offline business to smart e-commerce, TREs always outsource the developing tasks of digital marketing platforms to digital technology companies (Anand & Goyal, 2019). In this digital cooperation, the traditional SQ should be expanded to smart system level, thus, the novel comprehensive concept of DSQ was born (Büyüközkan et al., 2020), emphasizing emerging digital marketing technologies, such as real-time data integration, AI-driven personalization, and value co-creation (Buyukozkan et al., 2020). Different from the SERVQUAL focusing on offline reliability and responsiveness (Collier & Bienstock, 2006), DSQ exhibits a series of digital capabilities, such as dynamic customer insights, tailored experiences, and customer engagement in innovation.

Definition 1 DSQ refers to users’ subjective satisfaction in how digital services meet their digital needs. It is a dynamic construct that not only reflects the integration effectiveness in digital marketing life cycle but also concerns the outcomes of the digital service.

The DSQ of digital marketing platform represents the TRE’s satisfaction with the digital service functions of a systematic solution, such as real-time data collection, smart preference recognition, accurate customer portrait, precise marketing push, and AI. Emerging information technologies have made the most important developments in the field of interactivity through the shifting from general mass marketing to individual precise marketing (Demirel, 2022). According to user expectations on digital platform, DSQ highly relies on extracting information from big data to enhance marketing performance.

For example, during Alibaba’s Double Eleven campaign, DSQ manifested as the seamless alignment of technical performance and customer experience on its digital marketing platform. Real-time data collection ensures system reliability and sub-3-second latency. Smart preference recognition uses ML models to effectively predict purchase intention and significantly reduce customers’ acquisition costs. Precise marketing push servers’ dynamic advertisements to high-value segments identified via the Recency-Frequency-Monetary Value analysis. These DSQ-driven capabilities not only align with customer expectations but also demonstrate how big data extraction and AI integration contribute to measurable business outcomes (Kamble & Gunasekaran, 2020; Elia et al, 2022).

According to Büyüközkan (2020), the indicators of DSQ comprise five dimensions as follows: digital tangibles, digital trust, digital interaction, customer centricity, and reliability. Some indicators reflect the application of digital technologies in the supply chain, such as traffic, time spent on page visit, customer information assets, and packet loss rate. Other indicators present the improvement of marketing performance because of the application of digital technology, such as average transaction value, ROI, and customer acquisition cost.

The indicators in the digital tangibles dimension represent digitized equipment, facilities, and their digital properties (Büyüközkan et al., 2019). In particular, functionality reflects the availability of digital channel and service characteristics (Chan et al., 2020; Melović et al., 2021). Efficiency reflects the capability of providing suitable products and information with minimum effort (Liu et al., 2022; Varadarajan, 2020).

The indicators in the digital trust dimension represent the performance and the stability of the digital platform, which can be measured by network performance indicators such as packet loss rate, transmission delay, and throughput (Skaka‐Čekić et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2018; Alnawas & Al Khateeb, 2022).

The indicators in the digital interaction dimension consider the digital communication networks between companies and the supply chain members through digital platforms (Büyüközkan et al., 2019). Collaboration and mobile communication have been selected in this study to reflect the capability of digital interaction, which will be enhanced using digital technology in the marketing activities.

The indicators in the customer centricity dimension represent an “outside-in” approach through innovative service delivery experience to fulfill the customer’s emotional needs by putting them at the heart of an organization (Büyüközkan et al., 2019). In particular, customer segmentation measures the ability to understand precisely the customers’ preferences and shopping behavior, such as frequency, recency, and monetary (Si et al., 2015). Customer insights are used to measure the transforming ability from customer analysis into marketing performance.

The indicators in the reliability dimension consider the role of digital technology in achieving marketing objectives and reducing input costs (Büyüközkan et al., 2019). Some financial indicators, such as marketing ROI, marketing cost, and customer acquisition cost, are selected as the second-grade indicators. Some market performance indicators, such as international market share, trade competitiveness index, and revealed comparative advantage index, are included to reflect the improved performance after the trial operation on the digital platform.

This indicator system is designed to provide an evaluation framework for the core operational dimensions of digital platforms. However, as different enterprises may have varying strategic priorities and operational environments, organizations can adapt or supplement relevant indicators according to their development goals and business needs in practical applications, ensuring that the indicator system aligns closely with strategic objectives.

Note: Ns: Number of customers at the start of the period; Ne: Number of customers at the end of the period; Na: Number of customers acquired during the period; Nc: Number of chained customers in the given period; Nt: Total number of customers at the start of the period; Sc: overall marketing campaign costs spent on acquisition; St: marketing team salary; Ss: the cost of marketing software; So: overhead related to marketing (e.g. designers, consultants); CE: Company's Export; TCE: Total Company's Export; GE: Global Export; TGE: Total Global Export

Standardization and aggregation of DSQTo ensure additivity and consistency across diverse DSQ indicators (with varying units, ranges, and definitions), data standardization is required. Additionally, there are three kinds of quality characteristics: the large-the-better (L type), the small-the-better (S type), and the nominal-the-better (N type). Suppose that the tolerance interval of characteristic Y is [yl,yu], in which yl and yu refer to the minimum and maximum boundaries, μ is the optimal target value. Let ε be an infinitesimal positive number extremely close to 0. The standardized quality level of the large-the-better, small-the-better and nominal-the-better quality characteristics, qL,qS and qN, can be designed as

For aggregation, let n DSQ indicators have weights ωi(ωi≥0,∑i=1nωi=1). The DSQ can be comprehensively described as the weighted sum of qL, qS and qN.

Here, r∈[0,1]. If any quality performance of an indicator is not located in the quality interval, r=0. Only if the performances of all the quality characteristics meet the quality requirement r>0. Especially, if any metric is located at the boundary, r=ε→0+.

TRE’s perceived DSQ and optimistic preference concerning dual DSQ reference knowledgeTRE’s perceived DSQ based on prospect theoryAccording to the prospect theory, the participant’s gain-loss state significantly impacts psychological utility, especially when it faces reference level (Barberis, 2013). The essence of a user’s perceived utility is the outcome of the psychological accounting process determining the gain/loss interval through reference points and an asymmetric value function (Tian et al., 2022). Different from the “absolute utility maximization” assumption, perceived utility in the prospect theory reflects the differential psychological feelings regarding benefits and losses (Jin et al., 2024). In this study, TREs’ perceived DSQ represent principals’ subjective utilities—gain and loss—because of the dynamic comparison between DSQ and the external reference points.

In the digital service supply chain, the prospect theory can reveal how external reference knowledge influence TREs’ perceived DSQ. TREs may have reference knowledge based on past experiences, industry norms, or anticipated future scenarios. Consequently, the prospect theory can help TREs gain deeper insights into the psychological dynamics driving the preferences and choices. The prospect theory is essentially applied to model TREs’ preferences for adopting digital technologies in precision marketing in the digital retailing era. Consequently, perceived DSQ is conceptualized as the TREs’ subjective evaluation of the digital performance derived from digital marketing platforms, caused by the cognitive comparisons between actual DSQ outcomes and external reference points. Guided by the prospect theory (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981), the formation of perceived DSQ involves two interdependent psychological elements as follows: reference dependence and loss aversion. Reference dependence means that the TRE evaluates the DSQ not only in absolute digital performance but also relative to external knowledge as benchmarks. Loss aversion shows that negative deviations from reference knowledge can generate stronger psychological impacts than equivalent gains.

In particular, if the TRE’s DSQ is larger than an external reference, it will obtain the additional positive psychological benefit caused by leading position, and vice versa. Additionally, the distances between actual DSQ and external reference points can show the future development space and influence the TRE’s perceived DSQ as well. If the actual DSQ is lower than a referencing level, the TRE’s pessimistic perspective damages its perceived DSQ. As the gap is continuously changing, the TRE’s optimistic attitudes regarding external reference points are dynamically switching, which creates the varying dominance of external reference points.

If the TRE’s received DSQ level is r, let us assume that the DSQ reference point, such as industrial DSQ or competitor’s DSQ, is r0. The TRE’s perceived DSQ under the influence of DSQ reference point r0 is as follows:

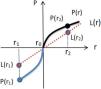

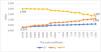

According to empirical data, α=β=0.88, and θ=2.25 (Barberis, 2013). The relationship between TRE’s perceived DSQ, P(r), and DSQ level, r, can be represented as shown in Figure 5, let P(r=r0)=0.

If there is no DSQ reference point, assume that TRE’s psychological utility is a linear function L(r),∂L∂r>0, L(r0)=0. As illustrated by Figure 5, the DSQ reference point enhances the TRE’s perceived DSQ brought by the gap between actual quality r and referenced level r0. In particular, when r=r1

In addition to its reference points, the TRE exhibits an optimistic preference—a behavioral propensity to prioritize future development potential over current performance gaps, which can be formalized through the second derivative of the value function

Definition 2: Optimistic preference is the decision-makers’ positive perception for future development, which is induced by the gaps between actual performance and reference levels. The TRE’s optimistic preference can be designed as follows:

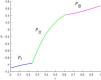

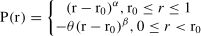

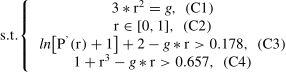

Suppose that industrial DSQ reference is rh and the competitive DSQ reference is rc, rmax=max{rh,rc},rmin=min{rh,rc}. As shown in Figure 6, TRE’s perceived DSQ caused by rmin and rmax are P1(r) and P2(r), which behaves the weight as λ1 and λ2. The second derivative of the value functions k1, k2 are

The weights of DSQ reference point are related to the optimistic preference coefficients, which reflect the TRE’s attitude on the future development potential of various DSQ reference points. If the TRE is in the lagging position, i.e. the perceived DSQ is positive but has a more promising future potential, it is more inclined to endure current unpleasant events and alleviate its sense of apprehension, which leads to a lower weight to this reference knowledge. If the TRE is in the dominance competition position, it experiences a more declining trend, the restricted opportunity for quality development will result in reduced prospects and less positive attitude on perceived DSQ. The changing dominant position of reference points creates varying weights of industrial and competitive psychological utilities, which can be designed as

The comprehensive utility function is

When r

When rmin≤r

Whenr≥rmax>rmin, the TRE’s DSQ is higher than all reference levels, which generates dual positive utilities, P1=(r−rmin)α>0,P2=(r−rmax)α≥0. According to the dual references rmin and rmax, the corresponding reference weighs are λ1=k2k1+k2 and λ2=k1k1+k2. Because the comparative larger P2 creates more satisfying feeling, P2 occupies more dominant position than P1, λ2>λ1.

Further discussion on geographic location and firm sizeLet us suppose that a targeted TRE, i, in a certain city, has determined its industrial DSQ, rh, and competitor’s DSQ, rc; its annual sale revenue is sri, and the city’s annual GDP is gdpi. To expand the reference knowledge to another firm in another city, the prosperity efficient and the scale efficient can be used to describe the influence of the TRE’s geographic location and firm size on external reference levels.

Prosperity efficient, θj, shows the influence of geographic locations, such as city j, on industrial DSQ, rh, comparing to that of the targeted city i. Let us assume that the annual GDP of city j is gdpj. The prosperity efficient equals the ratio of annual GDPs: θj=gdpjgdpi. If another TRE in city j wants to determine its industrial DSQ, rhj, it will be directly based on city’s industrial DSQ, rh, rhj=θjrh=gdpjgdpirh.

Scale efficient, ϑk, denotes the influence of firm size, such as sale revenue srk, on the competitor’s DSQ rh, compared to the targeted TRE i. Let us assume that TRE k’s annual sale revenue is srk. The size efficient can be set as the ratio of annual sale revenue, ϑk=srksri. If another TRE k determines its competitor’s DSQ, rck, it will be directly based on city’s industrial DSQ, rc, rck=ϑjrc=srksrirc.

Incentive mechanism for improving TRE’s DSQAfter achieving the TRE’s perceived DSQ, a “principal-agent” model describing the outsourcing cooperation between it and the DSP is established to explore the incentive mechanism, and the analysis process is demonstrated in Figure 7. Section 5.1 illustrates the benefits and costs of TREs and DSPs. In Section 5.2, the “principal-agent” model containing the cost-sharing incentive solution, individual rationality constraint (IR), and incentive compatibility constraint (IC) is designed to explore the cooperative relationship. In Section 5.3, the incentive solution design process is explored.

The incentive mechanism plays a crucial role in motivating the DSPs to improve the DSQ of the digital marketing platform and providing stronger marketing support for the TREs. Concerning the influence of the incentive mechanism, the DSPs actively strive to improve the DSQ from multiple dimensions. Specially, in the digital tangible dimension, DSPs can innovatively optimize the infrastructure and functional modules to increase the online review time and page visiting length. According to the digital trust dimension, they could optimize algorithms to enhance data security and service stability. In the digital interaction dimension, DSPs can update the interactive functions by developing interfaces for deep integration with social media and sharing modules. Referring to the customer centricity dimension, DSPs can improve the shopping data analysis models by developing intelligent systems. In the reliability dimension, DSPs could adopt novel analysis methods and develop evaluation, prediction, and competitive analysis tools to strengthen the platform’s competitiveness. Driven by technological innovation, the overall improvement in DSQ can be achieved.

However, the technology enhancement will generate additional beneficial investment. As the principals, TREs need to suitably consider the IR and IC. IR ensures the basic benefits of DSPs’ project participation, while the IC provides additional rewards on the DSQ improvement of the platform, prompting DSPs to continuously enhance the platform performance to meet the TREs’ marketing innovation and performance improvement requirements.

The cooperation benefit and cost of TRE and DSPIn the outsourcing process of digital platform development, TREs purchase digital marketing platform with a certain DSQ from DSPs with fixed payment and incentive reward. There are two kinds of constraints in cooperation as follows: IR and IC (Figure 8).

TREs’ benefit and cost compositionIn the outsourcing cooperation, TREs are primarily responsible for supervising the DSP to deliver digital platform development services that meet quality standards. However, because of the asymmetric information, to avoid the moral hazard of DSPs, TREs often need to pay a certain amount of incentive fees in addition to the fixed payment.

Perceived value-added benefitsTREs’ value-added benefits are positive at the DSQ level. According to the diminishing marginal utility, when the DSQ reaches a certain level, the increase of r will no longer bring an additional increase in economic benefits, inducing that the growth rate of TREs’ value-added income tends to be flat. TREs’ psychological utility is influenced by the external competitive reference points as well. Thus, TREs’ perceived value-added benefits can be described as φ(P(r)).

Fixed purchase fee to the DSPIf the digital platform is accepted, TREs will need to pay a fixed fee B to the DSP, which can be regarded as a constant.

Cost-sharing incentive feesWhen TREs perceive the additional benefit brought by the improved competitiveness of the digital platform delivered by the DSPs, they may be willing to pay additional DSQ incentive fee, ∅(r), encouraging the providers to continuously improve the digital service. The incentive fee, ∅(r), is positive with the DSQ level, r. ∂∅(r)∂r>0. However, the continuous increase of r will no longer bring additional increase in TREs’ economic benefits, inducing that the growth rate of the incentive fee, ∅(r), tends to be flat, ∂2∅(r)∂2r≤0. Cost-sharing incentive encourages DSPs to pay additional assurance cost because of the improvement of DSQ.

DSPs’ benefit and cost compositionIn the outsourcing cooperation, DSPs are responsible for providing the digital platform development service that meets certain standards. Their income is generated from TREs’ fixed purchase price and cost-sharing incentive fee.

To provide a digital platform that meets the certain standards, the DSP needs to invest resources in the research and development process, such as the construction of development environment, the formation of research team, the purchase of development equipment, and costs of quality testing and cost of system maintenance. These DSQ-assurance costs CS(r) are related to the DSQ level of the digital platform. Let us suppose that CS(r) is a monotonically increasing function to DSQ, ∂CS(r)∂r>0, ∂2CS(r)∂2r>0.

“Principal-agent” modelIn business relationships in a digital service supply chain, the TRE plays the role of a principal and authorizes a supplier to provide DSQ-satisfying services. In cooperation, there may exist different situations caused by different information asymmetry. The TRE and the DSP are performing the bargaining game about seizing the dominance of the digital service supply-chain transaction, which is directly related to their utility achievements and the equilibrium of the “principal-agent” problem. Let us assume that the TRE’s dominance weight is ω, ω∈[0,1], which is generally influenced by the competitive environment, cooperation strategy, and patent protection. Influenced by information asymmetry, the DSP can hide its DSQ-assurance investment and specific DSQ performance, which may harm the TRE’s comprehensive cooperation utility.

TRE is the buyer of digital marketing platform and expect effective control over outsourcing DSQ. To reduce the negative influence brought by asymmetry information, the TRE should design incentive solutions to induce the DSP into improving the DSQ. The purpose of incentive is to motivate the DSP to invest in proper DSQ-assurance resources, which can guarantee the optimal outsourcing DSQ and maximize the TRE’s perceived utility. Consequently, the optimal objective of the principal-agent model in the situation containing various information asymmetry contents is that the principal’s cooperative profit can reach the maximum, maximize{ωV[πT(r)]+(1−ω)V[πS(r)]}. In this study, the incentive objectives have been optimized, which not only include economic benefits but also take into account the influence of reference knowledge. Moreover, dynamic weights are set based on the TRE’s relative optimism toward different reference knowledge. The incentive objectives are transformed from single economic benefits to dynamic comprehensive utilities.

Additionally, to construct and maintain a business relationship between the TRE and the DSP, the following two kinds of constraints need to be considered:

Individual rationality constraint (IR)The IR is known as the participation constraint, which ensures that a mutually beneficial cooperation can be established between a principal and its agent. In the digital service supply-chain cooperation, the IR means that the DSP’s revenue should not be less than its opportunity profit in the market according to its capability and reputation. In other words, the profit, when the DSP cooperates with the TRE, should exceed the maximum benefit when it cooperates with others. Let us assume that the TRE’s and the DSP’s opportunity profits are πT‾ and πS‾, respectively. Considering the principal’s psychological utility, the individual rationality constraint can be expressed as V[πT(r)]≥V[πT‾], V[πS(r)]≥V[πs‾].

Incentive compatibility constraint (IC)The IC means the agent chooses its optimal behavior to pursue its maximum profit to maintain an efficient collaboration between the participants. Thus, the DSP selects its optimal DSQ-assurance capability, CS(r*), to maximize its profit, which can be obtained from ∂V[πS(r)]/∂r=0. Specially, assume that the DSP’s psychological utility depends only on its economic benefits, V[πS(r)]=πS(r).

Based on the above analysis, the principal-agent model between the TRE and the DSP is as follows:

maximize{ωV[πS(r)]+(1−ω)V[πT(r)]},(obj−I)

In the above programming model, the objective is maximizing the total utility of the service supply chain. The TRE’s psychological utility is its perceived DSQ, V[πT(r)]=φ(P(r))−B−∅(r), which is influenced by external references and varying reference weights. The DSP’s utility equals its cooperative profit, V[πS(r)]=πS(r)=B−CS(r)+∅(r). In the objective, ω is the TRE’s dominance weight. If ω=1, the TRE occupies absolute information power and creates completely symmetric information situation. If ω=0, the DSP owns the absolute information advantage, and the TRE has to accept the consequence of adverse selection. If 0<ω<1, the TRE and the DSP are seizing the cooperative dominance. Larger ω means the TRE gets the larger discourse power to realize its optimal utility in advance.

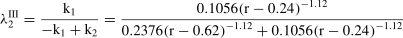

Additionally, the achievement of the objective strictly comes from the feasible domain, which comprises several constraints: C1−C4. C1 is the DSP’s IC, which means that it initially realizes its maximum utility by selecting its optimal DSQ investment. C2 and C3 are the TRE and the DSP’s rationality constrains, respectively, which present their minimal utilities as the bottom line. C4 describes the standardized DSQ, which is located in the tolerance interval. When ω∈(0,1), there will be the bargaining game between the TRE and the DSP.

The participants’ dominance positions can lead to the different numbers of ω.

If the DSP completely dominates supply-chain transaction, ω=0. In the complete asymmetric information situation, the DSP takes absolute advantage of private cost information, such as operational costs, quality assurance expenditures, and profit margins. In this scenario, the DSP may exploit its private cost information and determine its minimum investment to maximize its own profit in priority. Meanwhile, the TRE is at a disadvantage position in the cooperation and suffers from the bad feeling of adverse selection. The TRE has to accept the minimum contract-satisfied outsourcing DSQ and only obtain the opportunity to profit.

If the TRE completely possesses cooperation dominance, ω=1, a mandatory contract can be designed to assure its optimal utility. In the scenario of complete information symmetry, both the TRE and the DSP are clear on operational costs, quality assurance measures, and market dynamics. This transparency allows the TRE to determine its most expected DSQ, and the DSP should ensure specific investment and performance standards. Consequently, the DSP may only receive opportunity profit, πS‾.

If neither participant can fully achieve dominance in the digital service supply-chain transaction, ω∈(0,1), the TRE and the DSP will engage in a bargaining game and chase for dominance, which directly influences the equilibrium of the principal-agent relationship. The partly asymmetric information creates a situation where the TRE may possess superior knowledge about market conditions and customer expectations, while the DSP may have insights into operational capabilities and cost structures. This divergence in information complicates the negotiation process, as the TRE seeks to establish contract terms that protect its interests, while the DSP aims to secure favorable conditions that allow for adequate profit margins. Consequently, the principal-agent model plays a critical role in navigating the complexities of this relationship, helping to identify mechanisms that mitigate potential conflicts of interest and align incentives between the TRE and the DSP.

Incentive solution design processIn the cooperation process, the DSP prioritizes determining the DSQ that can achieve its own best benefit because of the information advantage. Later, the TRE concerns the behavior of the DSP and its maximum perceived benefits by designing incentive measures to reach the equilibrium of both participants.

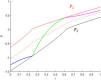

Step 1 (DSPs determine their optimal DSQ as the first-best): In cooperation, the increasing of DSQ indicates an increase in the assurance costs for the DSP, consequently, the DSP only provides a limited DSQ of digital services to maximize its own economic benefit. Let us assume that the first-best DSQ level determined by the DSP is r*, which can maximize DSP’s benefit. ∂V[πS(r)]∂r|r=r*=0.

Step 2 (TREs determine their optimal DSQ as the second-best): Let us assume that the TRE’s psychological utility will increase with an enhanced DSQ level, i.e., ∂V[πT(r)]∂r>0. Therefore, the TRE expects to obtain higher DSQ within the scope of the contract, in which IR (C3) is the hard constraint of the principal-agent model. When the TRE achieves its optimal psychological utility, there will be the second-best DSQ status r**, πS(r**)=πS‾, which can ensure all the constraints to be feasible. The TRE’s optimal DSQ level is not lower than that of the DSP, r**≥r*.

Step 3 (Bargaining equilibrium between the first-best and the second-best): Then, the DSQ equilibrium conditions are discussed according to the comparison between r* and r**.

- (1)

If the second-best DSQ level is equal to the first-best one, both participants can achieve their optimal benefit at the same DSQ. If so, the TRE no longer needs to adjust the payment condition. As a rational participant, the DSP will spontaneously provide a digital service at the level of r*, where r**=r*.

- (2)

If the first-best DSQ level is lower than the second-best one, the DSP is reluctant to provide a higher DSQ level because of the increase in the DSQ-assurance cost. In this situation, the TRE needs to adjust the payment and offer additional incentive to the DSP as a compensation for the additional cost of DSQ improvement. The incentive fee, ∅(r), can be positively linear and correlative to the DSQ level. The role of the incentive is to reduce the gap between the first-best and the second-best DSQs. Let Z=min{r**−r*} as the optimal objective, and the incentive fee, ∅(r), can be changed to maximize the TRE’s benefit, in which optimal incentive ratio can be calculated. The algorithm can be designed as shown in Figure 9.

As shown in Figure 10, Section 6.1 presents the condition of completely symmetric information, and the optimization on TRE’s psychological utility is discussed considering dual reference points. The incentive solution of “principal-agent” model in the condition of completely asymmetric information is analyzed in Section 6.2. In Section 6.3, the equilibrium of the transaction is explored under partly asymmetric information.

Incentive solution for improving the TRE’s DSQ in completely symmetric information situationIn the case of completely symmetric information, the TRE can directly observe the DSP’s DSQ-assurance investment and DSQ performance, which leads to TRE’s dominant position in the supply-chain cooperation. Through contractual agreement, the TRE can prioritize its optimal psychological utility without paying additional incentive costs. In this situation, the IR is a hard constraint, which ensures the cooperation can be realized. Concerning the impact of dual reference points and varying weights, the TRE’s psychological utility can be described as V[πT(r)]=φ(P(r))−B.

Theorem 1 Assume that there is r1*∈[0,1], the DSP’s economic benefit is equal to its opportunity benefit πS‾ and TRE achieves its optimal utility. Under completely symmetric information, the equilibrium of the transaction can be obtained at r1* concerning dual reference points.

Proof: As shown in Figure 6, TRE’s psychological utility is dynamically change due to the varying DSQ distance between the actual DSQ level and the reference level. According to the improvement of DSQ, TRE’s psychological utility will increase, ∂V[πT(r)]∂r>0. In symmetric information, TRE will prioritize maximizing its own utility due to the dominant position, in which DSP can only obtain the opportunity benefit πS‾. When r1*∈[0,1],the TRE reaches its optimal solution, i.e., r1**=r1*. Meanwhile, the DSP’s economic benefit is equal to its opportunity benefit πS‾, i.e., πS(r1*)=B−CS(r1*)=πS‾.

In the contract, the DSP will obtain the fixed fee, B, only when the deliver DSQ level, r, is no less than the specified level, r1*, i.e., r≥r1*. As the rational partner, the DSP pursues the higher economic profit and invests suitable assurance costs, which can also achieve the TRE’s optimal psychological utility, i.e. r1*=r1**. Proved.

According to the DSQ, r, the TRE can design a reward function, B, in a forcing contract to its supplier as

where πS˜ refers to the value which is sufficiently smaller than CS(r1*)+πS‾.Incentive solution for improving the TRE’s DSQ in completely asymmetric information situationIn the completely asymmetric situation, the DSP has the entire advantage of private cost information, which brings the discourse power. The TRE does not know any information about the DSP’s assurance information and profit. If so, the DSP will take advantage of private information and guide the transaction direction. Specifically, the DSP can firstly realize its maximal utility by determining its optimal choice of the cooperation. Then the TRE has to passively accept the DSP’s optimal combination if its opportunity profit can be realized. Consequently, the incentive solution design process needs to be proposed.

Step 1: In the condition of completely asymmetric information, DSP has priority to maximize its own economic benefits due to its dominance position in the supply-chain cooperation. Due to πS(r)=∅(r)−CS(r)+B, then ∂V[πS(r)]∂r=∅′(r)−CS′(r). Assume there exists r2*∈[0,1], in which satisfies ∂V[πS(r)]∂r|r=r2*=0; When r∈[0,r2*),∂V[πS(r)]∂r>0; Whenr∈[r2*,1), ∂V[πS(r)]∂r<0.

Step 2: The TRE’s psychological utility is positive with the increase of DSQ level, i.e,.∂V[πT(r)]∂r>0. Assume there exists r2**∈[0,1], where TRE's psychological utility reaches the optimal value. In this situation, the IC(C3) is the hard constraint to ensure the realization of the supply-chain cooperation, i.e., πS(r2**)=B−CS(r2**)+∅(r2**)=πS‾. Obviously, r2**≥r2*.

Under fixed payments, the TRE can only obtain a DSQ with the level of r2* due to the DSP’s moral hazard, which leads to the requirement for incentive mechanism. The improvement of DSQ can be induced by the cost-sharing incentive function ∅(r).

Step 3: TRE needs to pay additional incentive fee,∅(r), to DSP as the cost-sharing compensation for the cost of DSQ improvement. Suppose that the incentive cooperative equilibrium is obtained at r2, ∂Z∂∅(r2)=0. Once πS(r2)=B−CS(r2)+∅(r2)≥πS‾, the incentive function ∅(r) can drive r2* closing to r2**. As r2* and r2** are the functions with ∅(r), let r2*=f*(∅(r)) and r2*=f**(∅(r)). If r2*=r2**, both TRE and DSP will achieve their optimal benefit at r2*=r2**. If so, one can obtain the expression of ∅(r) by solving f*(∅(r))=f**(∅(r)), the optimal incentive intensity can be calculated.

Additionally, due to differential competition intensity, different TREs may concern the incentive budgets as another kind of constrain, which can moderate the incentive effect. Suppose that a TRE’s incentive budget is ρ, performing as the incentive threshold. The incentive budget constrain can be expressed as ∅(r)≤ρ.

Incentive solution for improving the TRE’s DSQ in partly asymmetric information situationIn the partly asymmetric information situation, neither DSP nor TRE is dominant in the cooperation, which induces a game between the participants. DSP can hide part of the cost and benefit information in this condition, while the TRE can also capture part of the DSQ assurance cost of the DSP. The status of the TRE is better than that of incomplete information, but weaker than that of complete information.

Step 1: In the condition of partly asymmetric information, the DSP has priority to deciding the delivery DSQ due to its partly dominance position in the cooperation. Due to πS(r)=∅(r)−CS(r)+B, then ∂V[πS(r)]∂r=∅′(r)−CS′(r). Assume there exists r3*∈[0,1], in which satisfies ∂V[πS(r)]∂r|r=r3*=0; When r∈[0,r3*),∂V[πS(r)]∂r>0; Whenr∈[r3*,1), ∂V[πS(r)]∂r<0.

Step 2: In this situation, the TRE and DSP are competing for the dominance position in cooperation, which is mainly related to the degree of information symmetry situation. Based on Section 4, TRE’s perceived DSQ P(r) can be obtained. According to the degree of information, the goal of motivation can be drawn as V1(r)=(1−ω)V[πS(r)]+ωV[πT(r)]. Due to V[πT(r)]=πT[P(r)]=φ[P(r)]−B−∅(r), V[πS(r)]=πS(r)=B−CS(r)+∅(r). Then V1(r)=(1−ω)(B−CS(r)+∅(r))+ω{φ[P(r)]−B−∅(r)}.

In the case of partly symmetric information, the TRE can obtain part of the information such as DSQ assurance costs and economic benefits of DSP. Therefore, the information advantage of DSP is weaker than that of completely incomplete information but stronger than that of complete information, which resulting in r3** meets ∂V1(r3**)∂r3*=0. When r∈[0,r3**), ∂V1(r)∂r>0; When r∈[r3**,1), ∂V1(r)∂r<0.

Step 3: The TRE needs to pay additional incentive fee,∅(r), to the DSP as the cost-sharing compensation for the cost of DSQ improvement. The incentive function ∅(r) can drive r3* closing to r3**. As r3* and r3** are the functions with ∅(r), let r3*=S*(∅(r)) and r3**=S**(∅(r)). If r3*=r3**, both the TRE and the DSP will achieve their optimal benefit at r3*=r3**. If so, one can obtain the expression of ∅(r) by solving S*(∅(r))=S**(∅(r)), the optimal incentive intensity can be calculated.

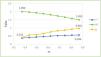

Numerical study and the result of the discussionBackground and data preparationThe study considered the following case to verify the proposed model in the stated conditions, which could demonstrate how external references could be integrated into a DSQ incentive framework. The assessment on the TRE’s perceived DSQ shows that the adoption of psychological utility can optimize the incentive goal and realize higher DSQ level under competitive environment. The prospect theory and the varying weight method were illustrated in Section 7.2 to analyze the influence of dual reference knowledge on the TRE’s perceived DSQ. A game-theoretic approach was utilized in Section 7.3 to examine cost-sharing incentive methods. A comparative analysis was conducted in Section 7.4 to evaluate different incentive models, and sensitivity analysis was applied in Section 7.5. Section 7.6 explores the influence of regional prosperity and enterprise scale on the incentive effect.

Let us consider the following example. As the TRE, the Jiebai group owned several offline shopping malls in Hangzhou city, Zhejiang province and met several business challenges in the digital economy, such as competition from online shopping, loss of precise consumer portrait, and inefficient marketing push. To enhance its DSQ, the Jiebai group cooperated with a DSP to develop a digital marketing platform. In the service supply chain, the Jiebai group was the principal and the DSP was the agent. During negotiation, they determined the development of KPIs in contract, such as CRR (unit: %), CAC (unit: million) and MC (unit: million), to aggregate the DSQ level. Through the analytic hierarchy process, the weights of CRR, CAC, and MC were determined as 0.4, 0.4, and 0.2, respectively. According to the results of the three-step design, the tolerance intervals of CRR, CAC and MC are determined as [10,30], [0.01,0.05] and [25,35], respectively, in which the corresponding target value is 30, 0.01, and 30. In Table 3, the raw information of KPIs, weights, tolerance intervals and target values are presented in the columns ①, ③, ④ and ⑤, respectively.

Through a marketing survey, a competitor’s and industrial service quality performances were treated as the external reference knowledge, which are listed the columns ⑥ and ⑧ of Table 3. According to Equation (1), the standardized level of competitors’ DSQ and industry average DSQ are illustrated in the columns ⑦ and ⑨ of Table 3.

Following the standardization process, the competitor’s standard DSQ and industry average standard DSQ can be calculated using Equation (1), with rc=0.62 and rh=0.24.

The influence of DSQ on the TRE’s comprehensive perceived DSQAccording to empirical data (Barberis, 2013), α=β=0.88,θ=2.25. Because rh

As r∈[0,1], the principal’s comprehensive perceived DSQ can be explored in the following three situations.

(1) Situation 1: The TRE’s actual DSQ is worse than both external reference levels (0≤r<0.24)

If r

Through Equation (6), the weights of dual reference points rh and rc are as follows:

Referring to Equation (7), the principal’s comprehensive perceived DSQ when 0≤r

If 0≤r<0.24, the principal’s received DSQ will be worse than external DSQ reference levels. Due to DSQ lags, P2II

(2) Situation 2: The TRE’s actual DSQ is in the middle between external reference levels (0.24≤r<0.62)

In this situation, the principal’s received DSQ is in the middle of the industry average DSQ, rh, and the competitor’s DSQ, rc. The principal’s perceived DSQ includes positive feelings brought by leading on rh and negative feelings caused by lagging behind to rc.

According to Equation (5), optimistic coefficients of P1 and P2 are as follows:

As k1<0, although there is a positive perceived DSQ caused by rh, limited development prospects could reduce the principal’s good feeling. Due to k2>0, even if the perceived DSQ is negative concerning rc, expected future potential and possible developing acceleration could mitigate the principal’s bad feeling.

Consequently, the weights of dual reference points rh and rc can be obtained through Equation (13) as follows:

Referring to Equation (6), the principal’s comprehensive perceived DSQ when rh≤r