This study investigates the factors influencing the adoption of assurance practices in sustainability reporting among leading companies across 42 countries from 2019 to 2022. Using panel data models, it examines the assurance lag, duality between the choice of audit firm and assuror for financial and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) assurance, and level of assurance (reasonable vs. limited). The results indicate that auditor–assuror duality may reduce the assurance lag through improved consistency and efficiency. However, this choice is not driven by expected benefits such as the inclusion of ESG information in annual reports or a preference for audit firms over consultants as assurors. Additionally, when audit firms follow specific assurance standards, there is evidence of a negative impact on the percentage of ESG information verified at the reasonable assurance level. This apparent negative impact is probably due to conservative approaches and strict methodological requirements. The findings offer insight to support decision-making for companies and regulators in enhancing transparency and trust in sustainability reports. This insight is particularly relevant in light of changes in European Union (EU) regulations that may impact assurance trends. Specifically, the new Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive allows for different options that may be transposed differently by EU member states. The study thus has valuable implications regarding the future regulatory environment in many contexts.

In the last decade, sustainability has become a pillar of global corporate strategies. Companies face increasing pressure from stakeholders, regulatory frameworks, and the need to align their actions with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These dynamics have driven an increase in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reporting. At the same time, they have exposed persistent challenges, such as the fragmentation of disclosure standards and the uneven implementation of sustainability assurance practices across jurisdictions (Farooq et al., 2024; Free et al., 2024a).

Given this context, this study explores three research questions. (i) What are the main drivers of the assurance lag for ESG information? (ii) What are the determinants of a company’s choice to hire the same firm for both financial statement auditing and ESG assurance? (iii) What factors shape the adoption of a reasonable assurance level for sustainability disclosures? By focusing on these questions, the study aims to comprehensively explain how regulatory, institutional, and organizational characteristics interact to shape current assurance practices in the context of the new European sustainability reporting landscape.

Using country-level data, this paper analyzes trends in sustainability assurance practices in leading companies from developed and developing economies. The analysis identifies the factors that influence challenges such as reducing the ESG assurance lag or ensuring a high level of assurance. The study also explores the role of hiring the same firm to undertake both sustainability assurance and financial statement auditing. The analysis draws on a set of theoretically grounded expectations regarding the relationships between institutional quality, regulatory frameworks, audit firm characteristics, and assurance outcomes. Specifically, the study investigates (i) whether higher institutional quality and regulatory development are associated with shorter ESG assurance lags. It also investigates (ii) whether market dominance and integrated reporting frameworks increase the likelihood of appointing the same firm for both financial and ESG assurance. Finally, it investigates (iii) whether the use of formal assurance standards, audit firm involvement, and the integration of sustainability disclosures in annual reports are linked to the adoption of a reasonable assurance level. The study thus provides empirical evidence on the mechanisms underpinning assurance decisions in an evolving regulatory environment.

The proliferation of sustainability reporting and assurance regulations, along with the use of digital technologies, is rapidly transforming sustainability assurance practices. Understanding current trends is vital for firms, regulators, and stakeholders to make informed decisions during regulatory changes. The timeliness of this study is highlighted by the approval (and transposition) of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) in the European Union (EU). The CSRD has already been or will soon be implemented in some countries, requiring EU member states to decide on the parties that can undertake sustainability report assurance within their jurisdiction. The CSRD aims to make sustainability reporting and financial information disclosure equally important. Therefore, the lag between the issuance of the audit and assurance reports may be expected to fall. The focus of this study is novel in accounting research. To the authors’ knowledge, although the audit lag has received much attention (Bhuiyan et al., 2024; Durand, 2019; Habib et al., 2018), this study is among the first to explore it in relation to assurance.

The current study is based on data from the largest listed companies from 42 countries (representing the world’s largest economies and some developing countries) over the period 2019 to 2022 (IFAC, 2023, IFAC, 2024). Based on analysis of these data, the results show an average lag of 58 days for the assurance of sustainability reports. This lag fell by an average of 52.73 days during the study period, reflecting progress toward greater alignment in reporting timeliness. This reduction signals the improved integration of financial and sustainability disclosures, although notable disparities persist across regions.

The primary contributions of this paper lie in advancing the ESG assurance literature by offering a framework combining multiple theories and empirical evidence from country-level panel data. By capturing temporal and cross-national variation, the study identifies region-specific patterns and institutional determinants that systematically influence assurance practices. The findings also offer empirically grounded insights to inform regulatory strategies and policy design, particularly in the context of the global shift toward mandatory ESG assurance frameworks. The current findings can be of use to policymakers. The analysis implies that audit–assuror duality reduces the assurance lag, which is unaffected by the level of assurance. Moreover, auditors are observed to be more likely to be hired to provide reasonable assurance. This finding is especially relevant in the EU, where reasonable assurance in 2028 will not be a requirement, as initially established in the CSRD. These findings can also be useful in other regions where the debate over whether to require reasonable assurance has not yet started.

Managerial implications can also be inferred from this research because companies must decide whether to hire consultants or auditors for ESG assurance and must decide on the assurance level. Regarding the assurance level, the study finds that hiring reasonable assurance does not increase the ESG assurance lag, which can be reduced if the financial statements auditor is the same as the sustainability report assuror.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the context of sustainability reporting assurance, outlining the situation in the present and the future. Section 3 reviews the literature and develops the hypotheses. Section 4 describes the data and variables used in the analysis. Section 5 presents the results and discussion, including analysis of the determinants of the ESG assurance lag, an exploration of the factors influencing auditor–assuror duality, and an examination of the factors driving reasonable assurance adoption for ESG disclosures. Finally, Section 6 concludes, summarizing the key findings and their implications.

Sustainability reporting assurance context: the present and futureESG practices are now essential in the global business environment. ESG strategy has become a matter of competitive differentiation among firms, promoting transparency and sustainable performance (Rezaee, 2016, 2024). Its importance has increased not only because of growing concerns over social injustice, sustainability, and environmental impact but also because companies must adapt to a more demanding regulatory environment and meet increasing stakeholder expectations around corporate social responsibility (CSR).

In the regulatory environment, the EU approved a groundbreaking directive (the CSRD) in December 2022, which has greatly expanded ESG disclosure requirements. The CSRD goes further than the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) and mandates reporting on ESG impact, promoting double materiality and transparency (EU., 2022). According to the CSRD, from financial years starting on or after January 1, 2024, large companies already subject to the NFRD will publish sustainability statements in accordance with the new European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) guidelines (EU., 2023). Gradual rollout is also set for other types of companies. Sustainability reporting standards are also being developed in the EU to oblige listed small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to report on sustainability and to make it voluntarily for non-listed SMEs.

According to the CSRD, sustainability statements will need to be externally assured (article 26a). Hence, a requirement of the CSRD is that sustainability information must be assured at least at a limited level.1 Initially, according to the CSRD, by 2028, assurance at a reasonable level may also be required in the EU. However, the omnibus package eliminated that proposal (EU 2025a, 2025b; Nicolo et al., 2025).

Thus, the CSRD requires the European Commission to adopt limited assurance standards before October 2026. Until then, no assurance standards will be adopted at the EU level, so EU member states can use national or international standards. To facilitate harmonization across the EU, the CSRD encourages the use of the Committee of European Auditing Oversight Bodies (CEAOB) for reporting (EU., 2022). They are the preferred voluntary guidelines on the procedures to express an opinion regarding the outcome of sustainability reporting assurance engagement. These guidelines were published in 2024 (CEAOB, 2024).

Another option that the CSRD provides for EU member states (paragraph 61) is relevant to this study. Each EU member state can decide whether sustainability report assurance may be performed only by auditors (which may or may not be the same as financial statement auditors) or also by non-auditing consultants or service providers.

Another novelty of the CSRD is that financial reports and sustainability information are expected to cover the same reporting period. The CSRD requires sustainability disclosures to be included in the management report, which the financial statement auditor must check. Hence, the dates of the financial statement audit report and the sustainability assurance report can be expected to be similar. The reporting lag and the difference between the dates of those reports can therefore be expected to decrease. It is hoped that this shorter lag will lead to higher-quality corporate reporting because both types of externally revised corporate information will be available to stakeholders. In particular, directors and managers will have a more comprehensive and connected view of financial and non-financial information.

When transposing the CSRD, EU member states have some other choices in addition to establishing who can do the sustainability assurance. For instance, they can increase the number of entities required to report under the CSRD (e.g., by thresholds or legal entity type), align requirements with local statutory filing requirements, or impose sanctions in case of non-compliance. These options can lead to increased comparability regarding assurance yet leave room for national variations and company choices.

EU member states had to transpose the CSRD before 6 July 2024. However, some (i.e., Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, Austria, Portugal, Luxembourg, and Malta) have not yet transposed it (Accountancy, 2025). This situation may delay the harmonization of sustainability reporting in the EU pursued by the CSRD, to the detriment of stakeholders that make decisions based on the sustainability profile of companies (e.g., investors, who are increasingly interested in firms’ sustainability performance).

At the global level, the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) issued two standards (IFRS S1 and IFRS S2) in 2023 (ISSB, 2023a, 2023b). These standards offer a unified framework for disclosing sustainability-related risks and strategies. They thus facilitate informed decision-making by investors and regulators, with a special focus on financial materiality and climate change risk (ISSB, 2023a, 2023b).

The most salient novelties in recent sustainability reporting standards are the CSRD and ESRS in the EU and the new IFRS S at the global level. However, many other frameworks are commonly used in sustainability reporting. Countries or stock exchanges may impose these frameworks for specific types of companies, and some companies may apply them voluntarily (Abhayawansa & Adams, 2021; Elliott et al., 2024). Some common frameworks for sustainability reporting are as follows: the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Together, these standards lead to a higher propensity to assure sustainability information, according to Krasodomska et al., (2024).

Bearing in mind the many possibilities for sustainability reporting, often on a voluntary basis, there are risks of greenwashing. Hence, sustainability assurance has also come to the forefront of the current debate (Bhullar et al., 2025; Free et al., 2024b; Pratama et al., 2025). The assurance of sustainability reports helps reduce information asymmetry between managers and shareholders, enhancing investor confidence and market liquidity (Jarboui et al., 2023; Mnif Sellami et al., 2019; Mnif Sellami & Dammak Ben Hlima, 2019). Companies that assure their sustainability reports have lower levels of information asymmetry, thereby facilitating better decision-making by investors. It provides a competitive advantage by demonstrating a company’s commitment to transparency and corporate responsibility. Sustainability assurance has also been shown to improve the financial conditions of companies in terms of, say, firm value, reducing the cost of equity or analyst forecast errors (Alduais, 2023; Datt et al., 2024; Garzón-Jiménez & Zorio-Grima, 2021; Luo & Pan, 2025; Thompson et al., 2022; Velte, 2025).

Several standards can be used for sustainability assurance, the most common being AA1000 and ISAE 3000 (Boiral & Heras-Saizarbitoria, 2020; Farooq et al., 2024; Sierra et al., 2013; Zorio et al., 2013). The Assurance Standard AA1000 was issued in 2003 by AccountAbility and tends to be used by consultants (Luque-Vílchez et al., 2023; Steinmeier & Stich, 2017). The International Audit Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) issued the International Standard on Assurance Engagement (ISAE) 3000, which is used for engagements other than audits or reviews of historical financial information. It is mainly used by audit firms that provide assurance services (Luque-Vílchez et al., 2023). They sometimes use ISAE 3410 on Assurance Engagements on Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Statements too. Apart from these AA or IAASB assurance standards, the International Standard for GHG Emissions Inventories and Verification (ISO 14,064) is increasingly being applied, given the importance of climate change disclosures (Gürtürk & Hahn, 2016). The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) has also developed a guide for assurance engagements of organizations’ sustainability information (Coville, 2021; Dilla et al., 2023).

Although standards such as AA1000, ISAE 3000, and ISO 14,064 provide robust frameworks for sustainability assurance and related disclosures, Gulko and Hyde (2022) found that, in practice, many companies do not uniformly implement these standards in full. This lack of uniform implementation is largely due to the flexibility in regulations and the prioritization of the needs of shareholders and institutional investors over other stakeholders. In addition, Gulko and Hyde noted that, although the importance of non-financial reporting has increased substantially, there remains a gap in the effective implementation of substantive reporting in key areas such as environmental impact, human rights, and governance. This contrast highlights the need for mandatory regulatory frameworks that ensure that CSR disclosure is taken seriously by companies. Such frameworks would complement voluntary initiatives with a more structured approach, also through compulsory assurance, as in the EU with the CSRD.

The IAASB has just approved the new International Standard on Sustainability Assurance, the so-called ISSA 5000 (2024). This standard will replace ISAE 3000 and will be overarching and framework neutral for verifying sustainability information and ensuring the quality of ESG reporting, distinguishing between limited and reasonable assurance levels (Venter & Krasodomska, 2024).

Double materiality, the approach followed by the ESRS in the EU, is a new concept. It requires organizations to assess not only how sustainability impacts their financial performance but also how their activities affect the environment and society at large. This paradigm shift enables a holistic understanding of corporate impact and ensures that reports more accurately reflect companies’ commitment to sustainability. This concept is somewhat covered in the ISSA 5000 (2024) but not in detail. It has therefore attracted some opposition in some of the comment letters to its exposure draft (e.g., Hay et al., 2024).

The international landscape of ESG assurance practices is characterized by jurisdictional differences. In the EU, the CSRD mandates limited assurance from 2024 onward, ultimately removing the requirement of reasonable assurance (EU, 2025a, 2025b). In the EU, external verification is required for both financial and sustainability reports through the audit of financial statements and the assurance of sustainability reports.

This section concludes with a comparative discussion. In the EU, member states can allow both auditors and non-auditors to provide assurance. However, they are advancing toward standardized sustainability assurance, assigning statutory auditors the responsibility of verifying consistency between financial and ESG disclosures in the management report, which must include the sustainability report. In contrast, practices in the United States remain fragmented and largely voluntary. Although both regions permit assurance by auditors and non-auditors, U.S. firms typically limit assurance to selected metrics (Gipper et al., 2025), rather than the entire sustainability report. This posture reflects a decentralized approach, where assurance is shaped by market forces rather than regulatory mandates.

In the United States, ESG assurance remains voluntary, fragmented, and primarily shaped by reporting frameworks such as GRI and SASB. The choice of assurance provider and the scope of verification vary depending on whether environmental or social metrics are being assured. Non-accounting providers dominate the assurance of environmental information, whereas accounting firms are more prevalent in social disclosures. Unlike the EU’s integrated and regulation-driven approach, the U.S. assurance landscape is characterized by selective verification practices, provider specialization, and a market-oriented logic focused on reputational signaling rather than regulatory compliance. Consequently, firms tend to choose partial assurance engagements that selectively cover specific dimensions of ESG performance as a response to market expectations rather than mandatory requirements (Gipper et al., 2025).

Sustainability assurance practices have regional differences in terms of scope, timing, and standards. In the Asia-Pacific region, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan have more than 80 % coverage in ESG disclosure assurance. In Latin America, Mexico has had double-digit growth in the adoption of such practices (2025; KPMG International., 2024). Regarding the adoption of mandatory assurance, Bangladesh and Turkey are as timely as the EU, making sustainability reporting assurance mandatory in 2024. Compulsory sustainability reporting assurance came into force in 2025 in Australia and Tanzania, in 2026 in Brazil, Mexico, Taiwan, and Pakistan, and in 2027 in Malaysia (Deloitte, 2025). These differences highlight the fragmented and evolving nature of the global ESG assurance market. They also underscore the importance of understanding how regional context, assuror identity, and timing influence assurance decisions.

Literature review and hypothesis developmentDifferent theoretical frameworks have been used to explain why companies submit their sustainability information to external assurance. Assurance research often applies these frameworks individually, but sometimes they are applied in combination (Bentley-Goode et al., 2025; Farooq et al., 2024; Velte & Stawinoga, 2017). The most popular theoretical frameworks in the research on this field are presented in this section.

Legitimacy theory is popular given that assurance is aimed at addressing pressure on firms to gain or maintain their reputation (García-Meca et al., 2024). Signaling theory has also been applied given that assurance signals to stakeholders that sustainability information is trustworthy because it has been verified by a third party (Krasodomska et al., 2024). Agency theory is also relevant, focusing on the conflict of interest resulting from the separation of ownership (Fama & Jensen, 1998; Tyson & Adams, 2020; Velte & Stawinoga, 2017). In this context, assurance is seen as a tool to minimize information asymmetry between managers and shareholders. Stakeholder theory goes a step further from agency theory by also considering stakeholders other than shareholders. It is applied more often than agency theory because it posits that companies are willing to show that they consider the views of a broad group of constituents (not only shareholders) in their management. Companies would thus provide assured information to enhance stakeholders’ decision-making processes (Hahn & Kühnen, 2013; Martínez-Ferrero & García-Sánchez, 2017).

Institutional theory suggests that corporate behavior does not necessarily follow a business rationale when assuring its sustainability disclosures but may instead be influenced by different types of isomorphisms (Chen & Cheng, 2020; Dimaggio & Powell, 1983). For instance, mimetism (or mimetic isomorphism) refers to the tendency of organizations to imitate their peers under uncertainty, seeking legitimacy and the alignment of their practices with accepted norms rather than improving efficiency (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). The theories of the symbolic view and the substantive view have also framed research on assurance (Mnif Sellami & Kchaou, 2023). The symbolic view is aligned with impression management, implying that assurance is used to convey a false image that projects transparency and reliability. The substantive view implies the opposite (i.e., that companies use external assurance for credible transparency motives).

The current research is framed within institutional theory and stakeholder theory, given that it explores the identity of assurors, the level of assurance, and the assurance lag. These aspects can all be expected to be influenced by regional trends and stakeholder expectations. Sector trends could not be analyzed in this study because the source for country-level data offered no industry breakdown.

The percentage of companies submitting sustainability information for external assurance has increased over the years, but differences remain between jurisdictions. For instance, in New Zealand, only 20 % of companies disclosing sustainability information apply any form of assurance. The New Zealand market is dominated by the Big Four firms, which generate large financial rewards such as higher market valuations and greater stock liquidity (Caglio et al., 2019). Meanwhile, non-accounting providers apply alternative standards such as ISO 14,064 to measure carbon footprints (Hsiao et al., 2022). Spain has been described as a leader in sustainability reporting and assurance (Zorio et al., 2013) and is one of the few countries in Europe with compulsory assurance (Accountancy, 2020).

In a market where global players compete for consumers and financial resources, this unlevel playing field highlights the need for greater standardization and accessibility of assurance frameworks to promote competition and similar approaches. Only then can stakeholders receive a clearer picture and avoid an expectations gap that may be exacerbated when considering the profile of the assuror, the assurance standards used, the level of assurance, and the timeliness of the assurance outcome.

The audit report lag is the time elapsed from clients’ fiscal year end to the audit report date. Specifically, it is the number of days that auditors take to finish the audit engagement since year end (Ashton et al., 1987; Durand, 2019; Knechel & Payne, 2001; Zhou et al., 2024). Research has confirmed that the time to finish the audit process influences the timing and value relevance of financial statements because it has an impact on information asymmetry in the market. Research on the audit lag has focused on clients’ profitability and financial situation, client complexity, and audit-modified opinion as variables that increase audit lags. In contrast, the audit lag decreases with client size, the existence of positive earnings, and long-tenured auditors that provide non-audit services (Durand, 2019).

However, to the authors’ knowledge, the lag in the assurance report has only just started to be explored. Mnif Sellami and Kchaou (2023) defined the assurance lag as the square root of the number of days between the end of the period covered by the report and the date of the assurance statement. They found that it increases if the readability of the report is low, especially if the assuror is an auditor. Nonetheless, in this study, the assurance lag is defined as the number of days between the issuance of the audit and assurance reports. The reasons for selecting this definition are data source availability and the new CSRD philosophy, whereby sustainability information is to be disclosed in the management report, which the statutory auditors of the financial statements supervise.

According to the research, the factors determining these decisions may be expected to be linked to regional trends, as well as to the fact that ESG disclosures can be included in the annual report. At the regional level, the EU CSRD will oblige firms to include the sustainability statement in the management report, which the auditor checks to confirm it tallies with the financial statements for that year and complies with applicable rules. Therefore, an effect of the regulatory changes is that both financial and sustainability reports, which are externally verified, can be expected to be published together in what is usually called the annual report. Regarding types of assurors and assurance standards, the CSRD gives member states some flexibility. However, it establishes that the EU should set its own limited assurance standards in 2026.

Some research has found that auditors provide higher-quality assurance reports (Harindahyani & Agustia, 2023; Zorio et al., 2013). Research has also found that the auditor’s experience (García-Sánchez et al., 2022) and longer assurance tenures (Martínez-Ferrero & García-Sánchez, 2017; Ruiz-Barbadillo & Martinez-Ferrero, 2023) can increase quality, value relevance, and ESG credibility for ESG raters (Kimbrough et al., 2024). Finally, studies have shown that auditor experience and longer assurance tenures enhance the positive effect that financial analysts attribute to ESG reporting (Tsang et al., 2024).

Fig. 1 captures the research questions of this study. These questions are framed in stakeholder theory (because of the different stakeholders involved in the sustainability reporting process and its effects) and institutional theory (because isomorphisms can be expected). These research questions are proposed to shed light on the changes in the regulatory environment outlined in Section 2.

RQ1: What factors influence the assurance lag for ESG information?

RQ2: What factors affect the decision to select the same firm for both financial statement auditing and ESG assurance (auditor–assuror duality)?

RQ3: What factors govern the adoption of a reasonable assurance level for ESG disclosures?

Despite the breadth of the literature, studies have not simultaneously examined the interrelationships between provider identity, the level of assurance, and the assurance lag from a cross-country and country-level perspective. Moreover, most analyses have not considered the effect of proliferating, converging (e.g., CSRD), and evolving assurance standards (e.g., ISSA 5000).

Thus, this study aims to addresses two research gaps: (1) the limited understanding of cross-country determinants of features of ESG assurance and (2) the underexplored role of provider type and audit integration in shaping assurance outcomes such as assurance lag. Three hypotheses are thus proposed and tested. Each hypothesis is stated and then justified.

H1. The mean ESG assurance lag in a country is influenced by the following factors: the propensity to disclose sustainability information in the annual report; other assurance characteristics (i.e., auditor–assurance duality, the use of reasonable assurance, and the applied assurance standard); and the level of absence of ESG reporting in the country and region.

The time elapsed between the issuance of the audit report and the sustainability assurance statement (i.e., the assurance lag) is a key indicator of both the credibility and responsiveness of assurance processes. This lag is a function of not only reporting timelines but also the complexity and interpretability of the sustainability disclosures themselves. Mnif Sellami and Kchaou (2023) noted that lower readability in sustainability reports tends to prolong the assurance process because providers must invest additional effort to interpret and validate the information. This phenomenon is particularly evident when the assuror is an accounting firm, suggesting that provider characteristics mediate the intensity of the assurance effort.

In a parallel stream of research focusing on financial audits, Li et al. (2025) identified a non-linear relationship between the lag in audit reporting and the extent of earnings management. Their findings suggest that shorter lags may be strategically used by management to conceal income-increasing practices, whereas longer lags tend to reflect more thorough auditor scrutiny. Although these insights relate to financial reporting, they can be applied to sustainability assurance, where prolonged reporting timelines may similarly reflect either organizational opacity or heightened professional diligence.

At the country level, it may be expected that the more companies have auditor–assuror duality or disclose sustainability information in the annual report, the lower the audit lag. Also the lag could be expected to be greater if there is a higher propensity to undertake reasonable assurance or a greater absence of ESG reporting. This greater absence of ESG reporting may denote low ESG awareness at the country level, which could also be influenced by the region. For instance, in Europe, higher sustainability sensitivity may be expected, so there should be lower assurance lags. Because different assurance standards imply different procedures, their effect on the assurance lag is controlled for in this research.

H2. The country-level likelihood of appointing the same firm for both financial auditing and ESG assurance (auditor–assuror duality) is influenced by the following factors: the country’s leading companies’ propensity to disclose sustainability information in the annual report; the country’s leading companies’ propensity to have an assuror who is an auditor; the type of assurance standard applied; and the level of absence of ESG reporting in the country and region.

Besides timing and professional efforts, an additional factor shapes the assurance process. This factor is the engagement of the same firm for both financial audits and sustainability assurance. This dual role may enhance efficiency through synergies and shared knowledge. However, it can also increase scrutiny, audit complexity, and expectations. Recent findings by Chen and Scott (2025) indicate that, although audit fees rise when financial and non-financial assurance are combined, audit lags remain unchanged, suggesting anticipated and integrated assurance work. Moreover, recent studies reveal that professional judgment and governance dynamics further condition the impact of such dual engagements, influencing both audit outcomes and assurance quality (Cameran & Campa, 2025; Chen & Scott, 2025).

Hence, it can be expected that, at the country level, more companies will have auditor–assuror duality if the following conditions hold: there is higher propensity in the country to disclose sustainability information in the annual report; the assuror is an audit firm; or there is a lower absence of ESG reporting, denoting higher ESG awareness at the country level or the regional level. Because assurance standards imply different procedures, their effect on assuror–auditor duality is controlled for in his study.

H3. The country-level likelihood of undertaking reasonable assurance is influenced by the following factors: the country’s leading companies’ propensity to disclose sustainability information in the annual report; the country’s leading companies’ propensity to have an assuror who is an auditor; the type of assurance standard applied; and the level of absence of ESG reporting in the country and region.

The adoption of a reasonable level of assurance in sustainability or integrated reports plays a role in enhancing stakeholder trust and reducing perceived risk. Darsono et al. (2025) demonstrated that integrated reporting assurance positively influences investment decisions by improving report credibility and transparency. Independent assurance strengthens the positive link between ESG disclosure and financial performance, while reducing firms’ cost of debt. These findings support the view that higher assurance levels function as a credibility mechanism in capital markets, aligning with signaling and agency theory by mitigating information asymmetry between firms and external users (Darsono et al., 2025).

Therefore, it can be expected that, at the country level, more companies will hire reasonable assurance services if the following conditions hold: there is higher propensity in the country to disclose sustainability information in the annual report; the assuror is an audit firm; and there is a higher propensity for ESG reporting as a result of higher ESG awareness at the country level or the regional level. Because assurance standards imply different procedures, their effect on the country’s propensity for companies to submit their ESG reporting to reasonable assurance is controlled for in this study.

Previous studies have not addressed these research questions at the country level. The decisions at that level might also be explained by low concerns over sustainability (proxied by national percentage of non-reporting on ESG), by the hiring of auditors to undertake ESG assurance, and the type of assurance standards used, as well as the level of assurance in the case of the assurance lag (Zorio et al., 2013). In addition, in the analysis of country-level data, it is assumed that the patterns observed in the adoption of assurance practices for ESG reporting may be driven by regional isomorphic dynamics.

MethodologyThis study is based on a sample of 1900 leading companies from 42 countries. Most of these companies publish sustainability reports and hire assurance services for their ESG information. The sample for this study was constructed using country-level data from the latest reports from the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC, 2024, IFAC, 2023) regarding the situation of sustainability assurance in the largest listed companies from 42 countries (developed and developing). These country-level data relate to companies from various regions and economic sectors, allowing for global analysis.

The data show compliance with assurance standards at the country level such as ISAE 3000, ISAE 3410, ISO 14,064, AA1000, and AICPA. These standards are used in the hypothesis testing. The data also show the adoption of reporting frameworks such as GRI, SASB, TFCD, and the SDGs. These frameworks are only used to explain the sustainability reporting scenario in the descriptive statistics. They are not reported in tables but are discussed in the next paragraph.

The adoption rates of different sustainability frameworks vary at the country level. GRI is widely adopted, with an average of 74.65 % (SD = 20.41). The SDGs have an average adoption of 76.01 % and a lower variability (SD = 19.22). SASB has a lower average adoption rate of 34.14 % and higher variability (SD = 25.51). The TCFD framework has an average adoption of 45.33 % (SD = 27.88).

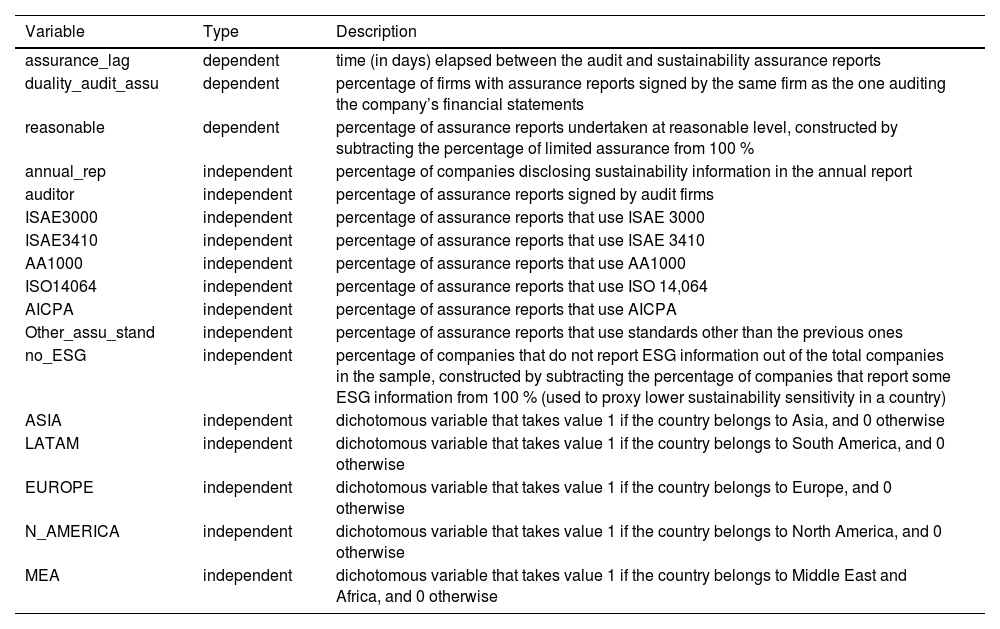

Data were gathered from IFAC, 2023, IFAC, 2024). They are defined in Table 1. The variables were collected at the country level for each year in the sample. Because the data were aggregated at the country level, the study had limited scope to examine sector- or firm-specific dynamics such as company size or industry effects. These limitations may affect the precision of the results and restrict the ability to generalize the findings to individual firms or sectors.

Description of variables.

Note: All variables in this table are directly sourced from the IFAC reports (IFAC, 2024, IFAC, 2023). The definitions and calculations are provided by IFAC.

The sample comprised 148 observations (42 countries over four years from 2019 to 2022). It constituted an unbalanced panel data matrix. The year 2022 was only available for G20 countries plus Spain, Hong Kong S.A.R., and Singapore. The year 2021 was not available for Russia. Some assurance information was not available for some countries in 2019 or 2020. Hence, the data for some variables were incomplete (Table 2). More than 33 % of observations were from Europe. Nearly 30 % of observations in the sample were from Asia. Only 5.4 % of the observations were from North America. On average, the countries in the sample had a lag of 58 days between companies’ issuance of the audit report and issuance of the sustainability assurance report. Audit firms signed 65 % of the assurance reports. In 62 % of the cases, the same firm signed both the financial statement audit report and the ESG assurance report. ISAE 3000 was the most widely used standard (70 % of cases) for ESG assurance.

Descriptive statistics.

Note. Obs. = number of observations. SD = standard deviation. assurance_lag refers to the days between audit and sustainability assurance reports. duality_audit_assu is the percentage of firms with assurance reports from the same firm that audits their financial statements. reasonable indicates the percentage of assurance reports at a reasonable level. annual_rep is the percentage of companies disclosing sustainability information in annual reports. auditor represents the percentage of assurance reports signed by audit firms. ISAE3000, ISAE3410, AA1000, ISO14064, and AICPA reflect the percentage of assurance reports using these standards. Other_assu_stand indicates reports using alternative standards. no_ESG is the percentage of companies not reporting ESG information. ASIA, LATAM, EUROPE, N_AMERICA, and MEA are regional dummies.

Panel data models are useful for capturing both longitudinal and cross-sectional dynamics. Considering the research questions and dependent variables, three panel data models were tested in Stata 14 software. Random effects panel data models were used to evaluate the impact of several variables on companies’ assurance decisions. This approach allowed for the inclusion of time-invariant variables such as region dummy variables that would be automatically omitted in fixed effects panel data models.

The models included independent variables such as the disclosure of sustainability information in annual reports (annual_rep) and lack of sensitivity to sustainability (no_ESG). These variables were included to analyze the factors affecting the assurance reporting lag time (assurance_lag), auditor–assuror duality (duality_audit_assu), and the reasonable level of assurance (reasonable).

The general estimated model to address RQ1 is defined as follows:

Here, assurance_lagi,t is the dependent variable for country i in year t, ai is the idiosyncratic error term, andui,t represents the random effects at the country or regional level.

For RQ2, the model is defined as follows:

For RQ3, the estimated model is defined as follows:

Results and discussionAnalysis of the determinants of the assurance lag in ESG reportsThe results in Table 3 provide detailed insights into the assurance lag, defined as the number of days between issuance of the audit report and the assurance report (IFAC, 2023, IFAC, 2024). The model was globally significant. No issues of multicollinearity were observed because the VIF coefficients were consistently less than 10. Additionally, the model had good fit, with an overall R² value of 48.5 %.

Random effects panel data model for the assurance lag (RQ1).

Note. Obs. = number of observations. SE = standard error. annual_rep is the percentage of companies disclosing sustainability information in annual reports. auditor represents the percentage of assurance reports signed by audit firms. duality_audit_assu is the percentage of firms with assurance reports from the same firm that audits their financial statements. reasonable indicates the percentage of assurance reports at a reasonable level. ISAE3000, ISAE3410, AA1000, ISO14064, and AICPA reflect the percentage of assurance reports using these standards. Other_assu_stand indicates reports using alternative standards. no_ESG is the percentage of companies not reporting ESG information. ASIA, LATAM, EUROPE, N_AMERICA, and MEA are regional dummies. *, **, and *** refer to 10 %, 5 %, and 1 % statistical significance.

The results in Table 3 show that the variables annual_rep and auditor did not significantly affect the assurance lag. This result indicates that the inclusion of ESG information in the annual report and the choice of consultant versus audit firm for assurance does not influence the time lag between the ESG assurance report and the financial audit report date. Contrary to expectations, the findings suggest that audit firms’ structural and operational advantages, such as standardized processes and specialized resources, do not lead to shorter assurance lags, nor do the theoretical time-saving benefits of including ESG reporting in the annual report.

When the audit firm performing the sustainability assurance was the same firm that audited the financial statements (i.e., the statutory auditor), the assurance lag was significantly lower, resulting in timelier reporting (duality_audit_assu). This negative significance highlights the importance of operational integration. Using the same firm for both the financial statements audit and ESG assurance enables collaborative efficiencies, such as streamlined processes, less redundancy, and enhanced consistency across engagements. Familiarity with the company’s structure and procedures further optimizes the assurance timeline, minimizing lags. Although this duality improves efficiency, it may raise concerns about auditor independence, which is important to maintain credibility in assurance practices. Among the control variables, the percentage of companies that did not report information on ESG (no_ESG) seemed to be positively related to assurance lag (i.e., lower engagement with ESG reporting in that region meant a higher average assurance lag). ESG reporting practices can vary between regions. Those with lower adoption of ESG reporting could encounter more challenges in the assurance process, reducing timeliness. The level of engagement with ESG reporting could indicate market maturity in terms of better and timelier sustainability assurance and transparency practices.

Finally, the assurance lag for European countries was significantly lower (with the Middle East and Africa used as benchmark in the model). This finding was somewhat expected given Europe’s leadership in sustainability regulations.

Determinants of the statutory auditor and assuror dualityTable 4 presents the panel regression results for the model exploring the determinants of the variable duality_audit_assu. The model was globally significant, and no multicollinearity problems were found (VIF coefficients all less than 10). The model had an overall R2 value of 23.5 %.

Random effects panel data model for auditor–assuror duality (RQ2).

Note. Obs. = number of observations. SE = standard error. annual_rep is the percentage of companies disclosing sustainability information in annual reports. auditor represents the percentage of assurance reports signed by audit firms. ISAE3000, ISAE3410, AA1000, ISO14064, and AICPA reflect the percentage of assurance reports using these standards. Other_assu_stand indicates reports using alternative standards. no_ESG is the percentage of companies not reporting ESG information. ASIA, LATAM, EUROPE, N_AMERICA, and MEA are regional dummies. *, **, and *** refer to 10 %, 5 %, and 1 % statistical significance.

Auditor–assuror duality could affect the perception of independence and the efficiency of the assurance process, so it is of interest to find its determining factors. The results of this section provide a comprehensive summary of the factors influencing the choice of the same audit firm.

The inclusion of ESG information in the annual report did not significantly influence the selection of the same audit firm. Thus, providing access to both financial and sustainability information in a single document did not affect the firm’s auditor selection (Outmane et al., 2024).

There was no significant relationship with the variable auditor. This result suggests that, in a given country, the percentage of companies selecting an auditor for ESG assurance does not affect the percentage of companies that choose the same firm to audit their financial statements. This finding could imply that decisions about who provides ESG assurance are made independently of decisions about financial auditing. Although companies can choose an audit firm for their ESG assurance, it does not mean that they will choose the same firm for financial auditing. This lack of a relationship could also indicate that the ESG assurance market is evolving differently from traditional financial auditing, with differences in ESG specialization among audit firms (Maroun, 2018).

Regarding assurance standards, a significant relationship with auditor–assuror duality was observed only for AA1000. As expected, this effect was negative because the AA1000 standard is mostly used by consultants (Boiral et al., 2020; Farooq et al., 2021; Farooq & de Villiers, 2019).

No significant differences were found between regions or in relation to sensitivity to sustainability through ESG reporting. These results suggest that the determinants of auditor–assuror duality are primarily negatively influenced by assurance standards, particularly AA1000, which is predominantly used by consultants. The absence of significant relationships with other factors, such as the inclusion of ESG information in annual reports and regional reporting variations, suggests that duality decisions are less about logistic or geographic influences and more about strategic and operational priorities. This finding indicates that the ESG assurance market is still evolving, with companies and auditors prioritizing expertise and tailored approaches over integration. The findings point to the need for further development of regulations on assurance practices that balance the benefits of specialization with the efficiency and credibility of dual engagements.

Factors influencing the adoption of reasonable assuranceThe third and last research question relates to the country-level factors that influence companies’ decisions to adopt a high level of assurance for their sustainability disclosures (i.e., reasonable assurance) instead of a low level (i.e., limited assurance). Table 5 displays the panel regression results for the model on reasonable assurance. The model had global significance, with no issues related to multicollinearity (VIF coefficients were less than 10). The model had strong fit, with an overall R² value of 72.7 %. This value suggests that the factors under study were driving decisions on reasonable assurance.

Random effects panel data model for reasonable assurance (RQ3).

Note. Obs. = number of observations. SE = standard error. annual_rep is the percentage of companies disclosing sustainability information in annual reports. auditor represents the percentage of assurance reports signed by audit firms. ISAE3000, ISAE3410, AA1000, ISO14064, and AICPA reflect the percentage of assurance reports using these standards. Other_assu_stand indicates the percentage of reports using alternative standards. no_ESG is the percentage of companies not reporting ESG information. ASIA, LATAM, EUROPE, N_AMERICA, and MEA are regional dummies. *, **, and *** refer to 10 %, 5 %, and 1 % statistical significance.

Including ESG disclosures in the company’s annual report had no significant effect on the percentage of companies opting for reasonable assurance. The potentially greater visibility of ESG information when it is included in the annual report does not seem to influence companies’ decisions to opt for reasonable assurance (Bouten & Hoozée, 2024). According to signaling theory, the findings may indicate that companies do not perceive reasonable assurance as a more robust signal of commitment. In contrast, from the perspective of stakeholder theory, the findings may suggest that investors and other stakeholders are not significantly influenced by the level of assurance when ESG information is included in the annual report.

Regarding the percentage of companies with assurance reports signed by audit firms, there was a significant negative relationship. These results suggest that, as the percentage of companies at the country level using audit firms for their assurance reports increases, the proportion of reasonable assurance decreases. Reasonable assurance entails more exhaustive and costly procedures. This finding can be explained because of the conservative behavior of audit firms. The ESG assurance market is in an early phase, where audit firms prefer to offer limited assurance while developing experience or hiring new staff to build more multidisciplinary teams and more robust methodologies. However, other professionals offer reasonable assurance as a differentiation strategy. Alternatively, reasonable assurance may present challenges in terms of cost and complexity. Companies may be considering whether the benefits of reasonable assurance justify the additional resources required to offer this service.

The application of certain assurance standards also affected the adoption of reasonable assurance. Standards such as ISAE 3000, ISO 14,064, and AICPA significantly negatively affected the percentage of reasonable assurance (Bouten & Hoozée, 2024; Grassmann et al., 2022; Hsiao et al., 2022). These results suggest that more intensive use of these assurance standards is related to a decrease in the percentage of reasonable assurance. In particular, ISAE 3000 provides detailed guidelines on the quality and depth of assurance work, offering a robust and structured methodological approach. ISAE 3000 establishes stringent requirements for evidence collection, risk assessment, and the issuance of an opinion that considers the reasonableness of reported figures and the integrity of internal control systems and governance processes. This rigorous framework can enhance the credibility of ESG reports while reducing the firm’s perception of the need for reasonable assurance.

Furthermore, a regional subgroup analysis revealed meaningful differences in the adoption of reasonable assurance. Specifically, companies located in Latin America had a significantly lower likelihood of adopting reasonable assurance than those in the Middle East and Africa, as indicated by the significant negative coefficient for Latin America (p < 0.05). The coefficients for Europe, North America, and Asia were not statistically significant. These findings highlight the relevance of contextual factors at the country or regional level and support prior calls to analyze global trends when evaluating assurance practices (Farooq & de Villiers, 2019; Hsiao et al., 2022). This heterogeneity highlights the importance of tailoring ESG assurance frameworks to regional contexts and considering local levels of institutional development, industry structure, and stakeholder pressure. Future research could expand on these insights through more granular sector- or firm-level analyses that further explore the drivers of assurance practices across jurisdictions.

Discussion of resultsGiven that this research is a pioneering study on the sustainability assurance lag and uses country-level data, the results are not directly comparable to the existing research in the field. The results in Table 3 suggest that the benefits of timeliness achieved through duality could outweigh the potential challenges of independence. Firms employing the same auditor for financial and ESG assurance can achieve more synchronized and credible reporting. Therefore, duality provides a practical strategy for addressing lags in the assurance process without sacrificing the quality of the outcomes (Bhuiyan et al., 2024; Sobhan et al., 2024).

In addition, opting for reasonable assurance does not significantly affect the assurance lag. The depth of analysis required to issue a more comprehensive judgment involves gathering more evidence and performing additional tests with a more detailed methodological approach as well as greater accuracy in the issued opinion. However, this apparent extra effort does not significantly affect the time needed for verification (Dal Nial et al., 2024; Dilla et al., 2023). This finding does not support the idea of a trade-off between the depth of analysis and the speed of the expected process. Given that reasonable assurance provides greater credibility and robustness to ESG disclosures, these findings may encourage companies worried about providing timely and credible sustainability information to stakeholders to request a higher level of assurance services, given that it does not imply a longer response time.

Theoretical contributions and practical implicationsThis study contributes to the literature by extending the concept of the assurance lag from financial auditing to sustainability assurance. It thus offers one of the first empirical examinations of the determinants of the assurance lag at the country level. The findings demonstrate that neither the inclusion of ESG disclosures in annual reports nor the adoption of reasonable assurance significantly affects reporting timeliness. This finding challenges the presumed trade-off between depth of analysis and speed of reporting. Furthermore, the evidence that auditor–assuror duality reduces the assurance lag highlights the theoretical relevance of operational integration, while raising questions about independence risks. This evidence thus links efficiency-oriented and credibility-oriented perspectives in the assurance literature. The study also advances institutional theory by revealing heterogeneity in the adoption of reasonable assurance across regions, particularly the lower prevalence in Latin America. Likewise, the study shows how assurance standards such as AA1000 and ISAE 3000 shape assurance choices in ways that segment the market between audit firms and consultants.

From a theoretical perspective, this study expands the application of signaling, institutional, and stakeholder theories in the field of sustainability assurance. The finding that reasonable assurance does not increase the assurance lag suggests that firms can use reasonable assurance as a signal of credibility and transparency without sacrificing timeliness, thereby reducing information asymmetry with stakeholders. At the same time, the negative association of AA1000 with auditor–assuror duality reflects the coexistence of different institutional logics in the assurance market, consistent with institutional theory. Furthermore, regional heterogeneity, particularly the lower prevalence of reasonable assurance in Latin America, highlights the influence of institutional maturity and stakeholder pressures. This finding extends stakeholder theory by showing how firms’ assurance choices respond to varying expectations of transparency and accountability across contexts. Together, these findings demonstrate that assurance practices correspond not only to operational or regulatory decisions but also to broader theoretical mechanisms of signaling commitment, institutional isomorphism, and stakeholder responsiveness.

From a practical perspective, the findings suggest that companies can enhance the credibility of their sustainability disclosures by opting for reasonable assurance without incurring additional reporting lags, thereby aligning timeliness and reliability. The evidence that using the same firm for financial and ESG assurance significantly reduces the assurance lag underscores a potential efficiency strategy for firms. However, regulators and standard setters must address the associated independence concerns to maintain trust in assurors. A relevant finding for policymakers is that diversity in assurance standards undermines comparability and global consistency, reinforcing the need for the convergence of initiatives such as ISSA 5000.

ConclusionsDespite efforts for convergence, harmonization, and interoperability among different sustainability reporting and assurance standards, comparing ESG disclosures of sustainability information remains challenging. The breadth of frameworks and assurance levels creates inconsistencies, affecting users’ ability to evaluate companies’ sustainability performance. The main contribution of this paper is its pioneering analysis of the assurance lag and its determinants. In addition, the paper contributes by presenting insightful analysis of other assurance decisions regarding service provider and assurance level (at the country level). The findings of this analysis are relevant for policymakers and companies, as this section explains.

According to the results, the assurance lag (i.e., the time from the audit report date to assurance) is not significantly influenced by the type of assurance. This finding may encourage firms to opt for reasonable assurance because it offers a higher level of certainty without affecting the timeliness of the assured information.

Regarding the type of assurance provider, the results indicate that using the same firm for financial and ESG assurance significantly reduces the assurance lag. This finding highlights structural and operational advantages of auditor–assuror duality. Additionally, the cumulative experience gained in financial statement audits gives a better understanding of the organization’s internal systems, thus accelerating the ESG verification process.

The results suggest that the decision to select the same audit firm for ESG report assurance is not conditioned by region and is mainly driven by not using AA1000 as an assurance standard. Additionally, in countries where audit firms are more likely to be selected as assurors, auditor–assuror duality is not necessarily higher. This finding has managerial implications. For example, differentiation strategies may be followed by independent consultants, or even auditors who differ from the statutory auditor, regardless of regulatory pressures or transparency expectations. This trend could suggest that ESG assurance market behavior differs from that of the traditional audit market, with a wider range of providers.

Despite the advantages of using country-level data to capture global trends and perform cross-national comparisons, this methodological choice has certain limitations. Aggregating the data at the national level restricts the granularity of analysis, making it impossible to control for firm-level heterogeneity such as company size, sector differences, and governance characteristics that may influence assurance practices. As a result, the findings should be interpreted with caution when generalizing to individual companies or industries. Moreover, data availability varied across years and regions (see Table 2). In particular, the years 2019 and 2020 had missing values for certain countries, which affected the temporal balance of the panel data set. This data limitation also meant that no robustness tests could be undertaken because no more variables were available in the IFAC’s reports. This limitation raises the need for future research if company-level data become available at some point in the future, such as in commercial databases with data on the assurance lag, assurance standards, or assurance level. Additionally, although the sample spanned multiple regions, certain countries or emerging markets may have been underrepresented due to data availability, which could introduce regional bias.

Another interesting direction for future studies could be to employ structural equation modeling to explore the mechanisms behind assurance choice. In addition, the assurance lag, which is a novel research area, could be further explored with archival data from companies, controlling for certain variables such as industry and company size. These variables were identified as especially relevant by Hay et al. (2023), who performed a meta-regression analysis on the choice of sustainability assurance service provider. Extending concepts rooted in auditing to assurance (e.g., the expectations gap) is another area that deserves attention (Free et al., 2024a; Hsiao et al., 2022). In particular, it would be of interest to examine the level of assurance (limited vs. reasonable) or the use of standards, perhaps considering these factors as moderators in the future.

The current findings highlight the need for standard setters to reduce diversity in assurance criteria and practices and provide clear guidance on how to express assurance statement opinions. Standard setters also need to provide clear guidelines on how to inform the public about the implications of the different levels of assurance. Disclosures and procedures would thus become more comparable, which, it is hoped, could reduce the assurance expectation gap. This narrowing of the gap would be a positive signal to the market (signaling theory), based on mimetism (institutional theory), in response to stakeholder interests (stakeholder theory).

Concerning assurance standards, the use of ISAE 3000 is found to reduce the prevalence of reasonable assurance in a country. This standard requires a thorough understanding of the business and an integrated approach to assurance. Therefore, it may enhance confidence in ESG assurance reports. Consequently, its application could reduce the perceived need for further assurance through reasonable assurance. This finding is consistent with those of Gürtürk and Hahn (2016), who also criticized the arbitrariness of assuring some content and the lack of transparency regarding the assurance process if ISAE 3000 is used. The recent publication of ISSA 5000 could help overcome these issues and improve the process. In line with institutional theory, the same type of normative and mimetic isomorphisms derived from socialization and common networks may be expected. However, coercive isomorphism may also become a factor if EU member states decide to impose this standard, as allowed for by CSRD.

In sum, despite ongoing efforts for convergence, harmonization, and interoperability among various sustainability reporting and assurance standards, achieving comparability in ESG disclosures remains a persistent challenge. The coexistence of multiple frameworks and varying assurance levels leads to inconsistencies that hinder stakeholders’ ability to assess companies’ relative sustainability performance. Thus, academic research such as the present study is important to advance the understanding of assurance practices and contribute to the broader goal of sustainable development.

CRediT authorship contribution statementViviana Paola Delgado Sánchez: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation. Ana Zorio-Grima: Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Paloma Merello: Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Project developed within the framework of the program of the Vice-Rectorate for Research of the UV, call for Special Actions- grant code UV-INV-AE-3663662 and under the research project PID2020-117792RA-I00 by the State Research Agency (Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation).