Digital entrepreneurial narratives compensate for the limited interactivity of traditional entrepreneurship narratives. This is achieved by incorporating elements of social entrepreneurship into tangible, real or fictional scenarios, thereby providing immersive experiences for the audience. In this sense, social entrepreneurs construct shared meanings and form socially identifiable values through the joint participation, communication, and value creation of entrepreneurs and audiences. We conceptualized the digital entrepreneurial narrative and proposed documentary and fictional narratives as its most salient features. Then, we explored the effect of these narratives on attentional resources in a digital entrepreneurial narrative from the perspective of sensemaking theory. Based on novel methods of natural language processing and machine learning, the empirical results from an examination of 304 social entrepreneurs who participated in the short-video platforms indicated that both documentary and fictional narratives have a positive impact on the acquisition of attentional resources for social entrepreneurship. Additionally, we found the documentary aspect of digital entrepreneurial narratives attracts attentional resources by fostering a shared sense of meaningfulness. However, the mediating effect is less effective with fictional narratives. Our results broaden the study of entrepreneurial narratives, and also expand the content of social entrepreneurial legitimacy and sensemaking perspectives.

Social entrepreneurship, as a type of social force engaging in governance (Mair & Martí, 2006), promotes the use of market methods to innovate and solve difficult social issues (McMullen & Bergman, 2017), taking into account both economic and social logics. The blend of multiple logics means that social entrepreneurs must not only skilfully acquire the support of a diversity of stakeholders who are typically rooted in complex logics, but they also have to achieve the operational coexistence of their logics (i.e., balance logics in organizational activities). Due to these constraints, current social entrepreneurship is still struggling to gain legitimacy in a situation where consensus is lacking among academics and practitioners (Nicholls, 2010). At the same time, social entrepreneurship is confronted with a significant scarcity of available resources.

The entrepreneurial narrative is a valuable source of legitimacy for entrepreneurs. In addition, it provides them with a key method of gaining access to resources (Zhao & Lounsbury, 2016). Using narratives to construct legitimacy further enhances a firm's ability to access resources (Lounsbury & Glynn, 2001). Scholars have extensively examined various aspects of entrepreneurial narratives. For instance, Zhao, Fisher, Lounsbury and Miller (2017) proposed ODT (Optimal Distinctiveness Theory), which can provide theoretical support for entrepreneurial narratives, assisting entrepreneurs in achieving optimal distinctiveness in their stories, and increasing stakeholder support and recognition. Furthermore, Taeuscher et al. (2022) investigated the legitimacy-building effects of optimal distinctiveness based on categories. Meanwhile, Bouncken and Tiberius (2021) examined how framing and trajectory can be adapted to meet the needs of different audiences for legitimacy-building purposes. Kuratko, Fisher, Bloodgood and Hornsby (2017)) examined the mechanisms by which dynamic legitimacy is built within the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Additionally, Taeuscher, Bouncken and Pesch (2021) raised questions about the opposition between legitimacy and uniqueness brought by ODT, and confirmed that narrative can enhance the legitimacy effect of uniqueness when there are no other sources of legitimacy.

These results provided novel insights for responding to heterogeneous audiences and constructing dynamic, interactive legitimacy. However, social entrepreneurship faces a more complex situation in terms of legitimacy gain than commercial entrepreneurship in the general sense. First, social entrepreneurship upholds a hybrid logic of commercial and social logics rather than multiple logics. As a result, category, which is a central aspect of the entrepreneurial narrative, is unable to effectively address the issue of legitimacy gain for an audience based on a hybrid logic. In fact, any category of audience is a complex subject with multiple logics. Second, existing social entrepreneurship still lacks consensus-based cognitive legitimacy, and this process is complex and lengthy, requiring constant construction. Existing entrepreneurial narrative strategies are struggling to achieve results across time and space. Third, social entrepreneurship faces an extreme scarcity of resources and needs to rapidly translate legitimacy into usable resources. Existing narratives of entrepreneurship are still improving in terms of their efficiency at transforming legitimacy. Thus, the central question we address is how to improve entrepreneurship narratives to help social entrepreneurship gain cognitive legitimacy and resources through a hybrid logic.

In recent years, new forms of digital narrative, represented by short videos and live streaming, have allowed the masses to express themselves freely and powerfully through the recording of real lives, vivid stories, and real-time participation (Ashman, Patterson & Brown, 2018). Moreover, digital narrative has enabled individuals to share their experiences and participate in real-time storytelling (Van Laer, Feiereisen & Visconti, 2019). It is clear that digitally empowered narratives continue to grow in power (Casalo, Flavian & Ibanez-Sanchez, 2020). As a result, social entrepreneurs and digital influencers are striving to develop innovative models for solving social issues using platforms. These patterns reflect the fact that the transmedia, connectivity, and virtual nature of digital technologies offer the possibility of narrative interactivity, hypermedia, and “pre-arranged textual and graphic systems based on user behavior”, providing a technological and conceptual metamorphosis of the entrepreneurial narrative phenomenon (Maclean, Harvey, Gordon & Shaw, 2015). Specifically, first, digital entrepreneurial narratives integrate graphics, audio, and images through digital technologies. The rich narrative and novel content form a full-bodied entrepreneurial story that can be presented visually and vibrantly to audiences. In contrast to traditional mono-media entrepreneurship narratives, digital entrepreneurship narratives can provide a hybrid logic based on a changeable narrative format that is easily accessible to different audiences. Second, digital entrepreneurship narratives offer the opportunity to communicate directly with audiences and to adapt the narrative content through interaction. In this process, audiences and entrepreneurs jointly engage in sensemaking, which facilitates the acquisition of recognition from different audiences and promotes social entrepreneurship to gain cognitive legitimacy. Third, digital entrepreneurship narratives can directly transform the cognitive legitimacy of scale into attentional resources through the platform effect, such as vloggers who can directly gain revenue through their traffic (Fotopoulou & Couldry, 2014). The purpose of this innovative and efficient solution is that social entrepreneurship is able to address the lack of resources. As a result, abundant digital entrepreneurial narratives have enabled social entrepreneurs to gain cognitive legitimacy and spread social value while acquiring attentional resources through sensemaking and compensating for the weaknesses of typical entrepreneurial narratives.

Our study examines the crucial role that digital entrepreneurship narratives play in acquiring attentional resources for social entrepreneurship. Specifically, by examining 304 short-form video social entrepreneurs, we uncover the mechanisms that impact legitimacy and resources in digital entrepreneurship narratives, revealing that both documentary and fiction narratives can gain attentional resources from the audience, wherein shared meaning plays a mediating role in this process. Consequently, this demonstrates the mechanisms through which digital entrepreneurship narratives impact the legitimacy and resources of social entrepreneurship. This research contributes to existing literature by extending the study of entrepreneurial narratives to digital spaces and addressing the unique challenges faced by social entrepreneurs in the acquisition of legitimacy and resources. Employing a sensemaking lens, we shift the research perspective from the common “category” and ODT in entrepreneurial narrative research to a focus on the particularities of legitimacy construction and effectiveness. Ultimately, our study provides valuable insights for social entrepreneurs to leverage digital narratives in navigating complex stakeholder relationships and efficiently translating legitimacy into resources. The purpose of this contribution is not only to expand the study of entrepreneurial narratives, but also to enhance the understanding of social entrepreneurial legitimacy and sensemaking perspectives, which represents a significant contribution to the current literature on social entrepreneurship.

Theoretical backgroundAttentional resources and social entrepreneurship resource acquisitionIn general, social entrepreneurship is most closely related to resource-limited areas (Di Domenico, Tracey & Haugh, 2009). In these areas, market demand may be insufficient to attract commercial entrepreneurs (Sunduramurthy, Zheng, Musteen, Francis & Rhyne, 2016). The process of acquiring social entrepreneurial resources inherently involves the spread of social value and influence, with a strong emphasis on social value creation and stakeholder involvement. Entrepreneurial narratives are a source of social entrepreneurship resources. The attainment of legitimacy, particularly cognitive legitimacy, is critical to this process. Cognitive legitimacy is established when an institution pursues aims deemed legitimate and desirable by society (Suchman, 1995). Constituent support for the organization is not motivated by their self-interest but, rather, by their assumed nature. However, as social entrepreneurship matures as a means of resolving social issues, legitimacy alone is insufficient to accomplish the critical work of social entrepreneurship resource acquisition and social value production. The key lies in changing and building cognition. As a result, social entrepreneurs must place greater attention on engagement and cooperation with other subjects throughout the resource acquisition and value co-creation processes (Drencheva, Stephan, Patterson & Topakas, 2021).

Attentional resources could be considered a kind of cognitive capital. Unlike legitimacy, attentional resources demonstrate not only the audience's acceptance of social entrepreneurs, but also the potential for user interaction and involvement. It is a significant indicator of the organic integration of legitimacy and resource acquisition. Attentional resources have grown into a significant opportunity for social entrepreneurs to build social wealth and spread influence over time (Petkova, Rindova & Gupta, 2013). On the one hand, in an era of burgeoning digital technology, attentional resources have become rare and valuable, in comparison to the information glut (Goldhaber, 1997). Not only are attentional resources deeply embedded in people's lives and manifested as a socialized lifestyle, they also irreparably alter the substance and meaning of public discourse, reshaping the channels and logic of social production. This has had a significant influence on human behavior and the remaking of social orders. As a result, attentional resources are critical to achieving the social objectives of social entrepreneurship. On the other hand, since attention is valuable, scarce, inimitable, and structured, social entrepreneurs may see attentional resources as obviously social resources, even if they differ from more typical corporate assets (e.g., financial, social, or intellectual capital) (Valliere, 2013). Decision-making and idea distribution are both reliant on attentional resources. As a result, the attentional resources of social entrepreneurs not only epitomize the cognitive legitimacy of social entrepreneurship and the acquisition of imperative resources, but are also an essential driver of social influence diffusion.

Digital entrepreneurial narrativeEntrepreneurial narratives are the processes by which entrepreneurs draw upon cultural resources of entrepreneurial events and experiences (e.g., discourse, language, categories, logics, and other symbolic elements) to capture the attention of, and convey meaning to, a targeted audience (Vaara, Sonenshein & Boje, 2016). Entrepreneurial narrative research has been exploring the means by which entrepreneurs can balance the unique aspects of their identity with the isomorphic pressures of the market through the use of optimal distinctiveness strategies (Taeuscher et al., 2022). Additionally, researchers have studied the development of audience legitimacy through the use of targeted rhetorical strategies that promote diversity (Fisher, 2020). Entrepreneurial ecosystem dynamics have also been examined in the construction of interactive, dynamic, and systematic legitimacy strategies that meet the expectations of complex markets (Bouncken & Tiberius, 2021). Finally, progressive and balanced legitimacy strategies have been proposed as a means of gaining collective support (Wood & Fisher, 2022).

The implementation of digital technology has resulted in the increasing enhancement of entrepreneurial narratives (Bouncken, Ratzmann, Barwinski & Kraus, 2020). On the one hand, according to Wilkin, Campbell, Moore and Simpson (2018), the creation, preservation, and sharing of stories in virtual environments composed of images, recorded audio, video editing, and music are gradually replacing oral and text-based narratives. The compatibility of digital narrative technologies, the interactivity of narrative forms, and the traceability of narrative trajectories allow digital entrepreneurial narratives to have processes that integrate digital media and technologies (Sanchez-Lopez, Perez-Rodriguez & Fandos-Igado, 2020). For example, Verk, Golob and Podnar (2021) argued that the large amount of social interaction facilitated by social media accumulates ample storytelling material. As a result, digital entrepreneurial narratives have greater potential for dissemination than more traditional forms (e.g., Ashman et al., 2018; Couldry, 2008; Lin & Chang, 2018; Robin, 2008). At the same time, this rich format will attract the attention of a more diverse audience than traditional media such as text and language, appropriately weakening the distinction between differential audiences and facilitating the blurring of barriers to access to legitimacy for different audiences.

Digital entrepreneurial narratives, on the other hand, incorporate their understanding of social entrepreneurship into concrete contexts by recording real or fictional stories, allowing audiences to immerse themselves in them and experience them mindfully. In the process of participation, audiences develop their own understandings, construct shared meanings through the process of communication with entrepreneurs, and form socially agreed values (Miranda, Young & Yetgin, 2016). In this sense, the gaining of legitimacy for digital entrepreneurship narratives goes beyond previous compliance with social norms and perceptions, and is an opportunity for entrepreneurs and audiences as a result of joint participation and value creation. This process creates a constructive legitimacy and resource gaining mechanism from an interactive perspective, enabling more flexible and effective ways of gaining audience buy-in and engagement.

The sensemaking perspective and social entrepreneurshipSensemaking comprises an investigation to identify coherent and memorable concepts, which represent a person's past experiences and expectations, as well as their self-identity, in order to connect with others (Weick, 1995). In other words, “To engage in sensemaking is to create, filter, frame, generate facticity, and turn the subjective into something more concrete.” (Brown, Stacey & Nandhakumar, 2008). Narratives are especially important for meaning construction in organizations (Fisher, Neubert & Burnell, 2021). As defined by Vaara et al. (2016), in their comprehensive review and summary of the literature, individual, social, and organizational sensemaking and sense-giving are enabled through organizational narratives.

The idea that social entrepreneurs use digital entrepreneurial narratives to help them make and share meaning and, thus, gain legitimacy and resources is central to differentiating entrepreneurial narratives from the former ones. Digital entrepreneurship narratives construct sense in a variety of ways, both temporal and interactive. It might be a component of larger social narratives that propagate prevailing values and ideas. However, few researchers have focused on the link between sensemaking and social entrepreneurship. In research that has been conducted, social entrepreneurship has been regarded as the commonality of beliefs and collective sensemaking that comprise individuals’ senses (Valliere, 2017). The discourse of social entrepreneurs is more other-oriented, stakeholder-engagement- and justification-oriented, and less self-oriented, than the vocabulary of commercial entrepreneurs. Furthermore, religion in social entrepreneurship is positioned as a tool for spiritual sensemaking, which may influence people's present and future activities (Sabbaghi & Cavanagh, 2018). Therefore, it is reasonable and meaningful to study the mechanism of digital entrepreneurial narrative on the acquisition of social entrepreneurial resources and value diffusion from a sensemaking perspective.

Hypothesis developmentDigital narrative's process of obtaining attentional resources reflects the sensemaking and sense-giving mechanisms. It may depict the process of social entrepreneurial meaning construction vividly, thoroughly, and authentically, gaining more effective attentional resources via interaction and feedback, and then leveraging other resources, to accomplish the dissemination of social value and impact. In digital entrepreneurship narratives, two forms of expression are demonstrated in the diverse narrative forms in which digital technologies are organically combined with the mediums of image, video, sound, and text. One is the use of digital multi-media as a vehicle for approaches that aim to highlight the value and authenticity of social entrepreneurship (Symon & Whiting, 2019), such as live entrepreneurship streaming and live documentation. The other is the use of diverse digital media as a means of incorporating a person's core ideas and feelings into the telling, storing and communication of entrepreneurial stories (Bell & Leonard, 2018), such as episodic short videos. Therefore, documentary narrative and fictional narrative have played different roles in this mechanism.

Documentary narrative refers to entrepreneurs capturing their real-life and social entrepreneurship activities via film, audio, text, and other media to educate audiences (Dessart & Pitardi, 2019). The narrative form generally appeals by including facts and logic, and communicating in a pragmatic or rational way. On the one hand, using documentary narrative entrepreneurs may authentically explain their individuality and the entrepreneurial process and meaningfulness to their audiences, while also engaging them by showing the world through the entrepreneurs’ eyes. According to some studies, informative appeals result in stronger purchase intentions compared to other types of appeals (Golden & Johnson, 1983).

The use of factual evidence may elicit greater trust than discourse evidence in certain situations (Allen & Preiss, 1997). Similarly, Holbrook (1978) argued that the authenticity of information triggers positive belief formation in marketing compared to static attitudes. Likewise, the research by Stubb (2018) indicated that when bloggers comment on sponsored products, the narrative information format increases blog readers’ browsing time for sponsored posts compared to the informational format. On the other hand, the authenticity of documentary narration may provide consumers with a stronger visual impact and innovation experience, while also enhancing audiences’ sensitivity and empathy for societal concerns. Individuals must integrate information from several sources in order to comprehend its meaning in multimodal communication; consequently, they become more engaged. Additionally, the employment of numerous formats may result in a greater degree of narrative comprehension and persuasion compared to communication that is based on text material alone (Dessart & Pitardi, 2019). Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 1a Documentary narrative is positively related to the acquisition of attentional resources.

Fictional narrative is a way for entrepreneurs to choreograph and perform unique tales to explain the value and significance of their businesses. Fictional narrative is defined by “giving material a rhythm and an interesting narrative framework, but in particular a wide variety of stimuli and information that enables a broad audience to be involved” (Clarizia, Colace, Lombardi & Pascale, 2018). The images in a story act as landmarks to direct the audience through the story's many sections, ensuring the plot's consistency and aiding in the translation of a person's private experiences into general questions, with an advising and encouraging aim (Porto & Belmonte, 2014). Creating a story may, in certain cases, assist audiences from varied cultural backgrounds to better grasp the purpose and significance that social entrepreneurs strive to accomplish. The plot, characters, and verisimilitude of the narrative, on the other hand, entail the development of rich metaphors in a certain sequence, stimulating receivers’ cognition, emotions, and behavioural reactions and prompting collective attention and participation (Dessart & Pitardi, 2019). Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 1b Fictional narrative is positively related to the acquisition of attentional resources.

As an essential manifestation of sensemaking for entrepreneurs and audiences, a shared sense of meaningfulness is sequentially generated from a common emotion and a shared representation, including emotion formation, emotion sharing, and sense expression (Lepisto, 2021). It represents the interaction and feedback between social entrepreneurs and audiences, as well as the interplay between sensemaking and sensegiving.

Documentary narrative not only engages the audience cognitively, but also arouses the audience's emotional energy through the presentation of real-world circumstances. Emotional energy is socially generated and is defined as “a sense of security, bravery to act, and boldness in initiating. It is a morally charged force that makes the person feel not merely good, but elevated, with the sensation of accomplishing what is really essential and useful” (Lepisto, 2021). When emotional energy is channelled through a collection of true images, meaningfulness is sparked and driven (Lepisto, 2021). A perceived shared sense of meaningfulness can be created via the transmission of an asocial mission statement, which may be seen as an entrepreneur–audience interactive sense-giving process. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 2a Documentary narrative is positively related to the audience's shared sense of meaningfulness.

The requirements for producing a good narrative provide a plausible frame for sensemaking (Weick, 1995). On the one hand, fictional narrative promotes customers’ perceptions of the value of social entrepreneurship. An interesting and inspiring narrative raises the social problem from simply being a difficult topic, stimulates people's ideas and conversations about the connotation of social worth, and then builds a shared sense of meaningfulness throughout communication and interaction. On the other hand, stories posit a history process for the outcome, and gather strands of experience into a plot that produces that outcome. The plot follows the sequence of either beginning–middle–end or situation–transformation–situation. However, the sequence is the source of sense (Weick, 1995). The cross-situational nature of stories allows audiences from diverse backgrounds to add their own understandings, widening the breadth of social entrepreneurs’ objectives and strengthening their understanding of social values (Cai, Luo, Fu & Fang, 2020). Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 2b Fictional narrative is positively related to the audience's shared sense of meaningfulness.

Once a shared sense of meaning has been created, entrepreneurs and audiences will have built a compelling narrative in accordance with social cognition, creating a new “niche” and increasing the reach of social entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurs and audiences alike strive to reinterpret social problem-solving methods by highlighting the importance of both individual initiative and environmental impact. Thus, subjective perception is capable of withstanding objective uncertainty and turning it into a probabilistic and predictable future that draws in a wide range of attentional resources. On the other hand, this niche formed of entrepreneurs and audiences has increased rapidly through the propagation and dispersion of the platform algorithm. The cognitive niche has drawn more recommendations and attention. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 3 Shared sense of meaningfulness is positively related to the acquisition of attentional resources.

Hypothesis 4 Shared sense of meaningfulness mediates the relationship between digital entrepreneurial narrative and acquisition of attentional resources.

Fig. 1 shows the research hypotheses of this article.

MethodologyData and sampleWe obtained the data from Kwai, the first short-form video portal platform in China, whose purpose is to “embrace various lifestyles”. Kwai has evolved into the leading video social network for BOP (Bottom of the Pyramid) groups (farmers, the elderly, the disabled, etc.). As there is currently no universal definition of social entrepreneurship, we identified qualified vlogging entrepreneurs based on the categories recognized as social entrepreneurship. Social entrepreneurs usually try to help broad social, cultural, and environmental goals, like reducing poverty, improving health care, and building stronger communities (Thompson, 2002). According to the definition and identification guidelines for social venture, we first examined the characteristics of social entrepreneurship from a commercial perspective and considered the vloggers who founded the store as a potential social entrepreneur. Then, we conducted a keyword search on the vloggers’ name and profile sections, using the terms “village official”, “assisting agriculture”, “supporting people with disabilities”, “assisting rural revitalization”, “volunteering”, “spreading the love”, and “protecting the environment” to identify social entrepreneurs. Simultaneously, we performed a second check of the vloggers’ videos. Finally, we chose 304 vloggers that represented social entrepreneurs on the Kwai platform. We then collected basic information about the vloggers, including their gender, age, field, and certification using python 3.0 tools from December 2021 to March 2022. We downloaded the videos and comments of each vlogger and collected basic information about each video, including the number of plays, likes, fans, forwards, etc. In addition, we collected live broadcast information about the vloggers, including the number of live broadcasts they had held and their sales of live products.

Variable measurementDependent variableAccording to research by Lou and Yuan (2019), the number of followers is a significant indicator of the influence of social media influencers and also represents audience engagement. The quantity of followers is an essential resource for social media influencers. Consequently, we calculated each entrepreneur-vlogger account's total number of followers (Attres) as an indicator of attentional resources.

Independent variablesBased on existing research, we analysed the textual content of vloggers’ videos and identified “seed words” associated with documentary and authenticity in the short films. The research by Bradbury and Guadagno (2020) on documentary narratives led us to extract words such as “real”, “at the scene”, “genuine”, “recorded”, and so on. As a consequence of their social entrepreneurial properties and the articulated claims of authenticity, current narrative research on coworking spaces and crowd spaces uses scales and codes as references for the construction of documentary narrative seed words (Bouncken & Kraus, 2022; Bouncken, Aslam, Gantert & Kallmuenzer, 2023; Gantert, Fredrich, Bouncken & Kraus, 2022).

Based on the above studies, we extracted words such as “live”, “witness”, “experienced”, and so on. Then, a training algorithm model was constructed based on the KMeans algorithm in cluster analysis. To train a corpus of documentary narratives, we utilized the Word2vec model in machine learning to process these seed words. The lexical technique was then utilized to compute the frequency of documentary-related terms in the short-video text material, which served as a measure of documentary narratives (DocNarr). We retrieved the seed terms of fictional narratives based on Van Laer et al. (2019) and Sanchez-Lopez et al. (2020): “story”, “comedy”, “humor”, “composition”, and so on.

Furthermore, fictitious narratives shift from pan-subjectivity to entrepreneurial subjectivity, with identity narratives being a particular example. We distilled key words such as “dreaming”, “pain”, “towards”, and “encouragement” based on the research of Bloom, Colbert and Nielsen (2021) and Saylors et al. (2021) on identity narrative. Additionally, fictitious narratives rely on non-material abstract concepts. Therefore, we developed seed words like “crescendo”, “fate”, and “craft” based on abstract vocabulary in entrepreneurial everyday life (Hakala, O'Shea, Farny & Luoto, 2020). A similar methodology was used to compile a vocabulary of fictitious narratives in text material of short videos. Lastly, word frequency data were used to determine the level of fictional narratives of vloggers (FictNarr). The lexicon of documentary and fictional narratives is shown in Fig. 2.

Mediator variableThe shared sense of meaningfulness reflects the audience's response and involvement with the substance of the vlogger's entrepreneurial story, which is more apparent in the comments. We generated seed terms based on the description of sensemaking in Lepisto (2021) and Weick (1995). The sense of meaningfulness lexicon was then trained using a word2vec model. The shared sense of value (SSoM) was determined by the frequency of terms in the lexicon that appeared in comments. Fig. 2 shows the lexicon of shared sense of meaningfulness.

Control variablesDrawing on previous research, we used gender (Gender), age (Age) and the platform certification identity (Certif) as individual-level control variables. We used the richness of the dependant content (number of video tags NarrRich) and the duration of vloggers from the first video posted to the most recent video (NarrDur), the fields of short-video content (Field), and the total number of videos posted by vloggers (NarrScal) as control variables at the level of entrepreneurial narrative content. The measurements and sources of the variables are shown in Table 1.

Summary of variable measurements and sources.

| Variable type | Variables | Description | Measurements | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Attentional resources | AttRes | Vlogger's total number of followers | Lou and Yuan (2019);Ki, Cuevas, Chong and Lim (2020) |

| Independent variables | Documentary narrative | DocNarr | Word frequency statistics based on documentary narrative lexicon | Pizer (1971);Bouncken et al. (2023);Gantert et al. (2022); Bouncken, Brownell, Gantert and Kraus (2022) |

| Fictional narrative | FictNarr | Word frequency statistics based on fictional narrative lexicon | Bloom et al. (2021); Sanchez-Lopez et al. (2020); Van Laer et al. (2019);Hakala et al. (2020);Saylors et al. (2021) | |

| Mediator variable | Shared sense of meaningfulness | SSoM | Word frequency associated with “meaning” in user comments | Lepisto (2021) |

| Control variables | Gender | Gender | Vlogger's gender | |

| Age | Age | Vlogger's age | ||

| Certification | Certif | Platform certification identity | ||

| Narrative richness | NarrRich | Total number of tags of vlogger's video | ||

| Narrative duration | NarrDur | Duration of vlogger's registration on the platform | ||

| Field | Field | Field of short video content | ||

| Narrative scale | NarrScal | Vlogger's total number of videos |

We used Stata 15.0 to conduct OLS multiple linear regressions. We split the empirical test of this research into two phases. The first stage entailed examining the direct influence of documentary narrative and fictional narrative on attentional resources (Hypotheses 1a and 2a). The second step was to test the mediating effect of the shared sense of meaningfulness, including the relationship between documentary narrative, fictional narrative, and shared sense of meaningfulness (Hypotheses 2a and 2b) and the correlation between shared sense of meaningfulness and attentional resources (Hypothesis 3).

In total, 304 samples were returned. Females accounted for roughly 25% of the data gathered, while males accounted for more than 74% (SD = 0.44); the age distribution spanned from 19 to 77 years old, with an average age of 36 (SD = 9.93). We applied the concept and evaluation criteria of social entrepreneurs to the selection of short-video vloggers. These videos focused on topics such as adoration, cuisine, life, entertainment, talent, tourism, emotion, and so on. The average number of video content tags was 7.4 (SD = 3.61). The average duration of a vlogger's registration was 33.79 months (SD = 13.48) and 55.6% of vloggers had been certified by the platform (SD = 0.50). The average number of videos posted by each vlogger was 414.4 (SD = 642.25). As shown in Table 2, the correlation coefficient with other variables and attentional resources was less than 0.4, indicating that this had no effect on the outcomes of the multiple linear regression analysis.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations.

The empirical regression results are shown in Table 3. The linear model in the first column, “Baseline”, only includes control variables. Most control variables showed significant p-values. First, we tested the main effects of documentary narrative and fictional narrative on attentional resources. The findings of models 1 and 2 reveal that documentary narrative and fictional narrative have a significant positive effect on attentional resources (β1 =65,286.3, p1 < 0.01; β2 = 110,133.7, p2< 0.01), respectively. This demonstrates that H1a and H1b are supported. The above models exhibited statistically significant F statistics and adequate increases in the adjusted R-squared value, hence the result was deemed to have explanatory power and reliability.

Regression results.

| AttRes | SSoM | AttRes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| Gender | −2.70e+05 | −3.48e+05 | −2.47e+05 | 36.92 | 69.62 | −3.37e+05+ | −3.68e+05 | −2.93e+05 | −3.10e+05 |

| (−1.38) | (−1.52) | (−0.87) | (0.84) | (1.27) | (−1.75) | (−1.61) | (−1.04) | (−1.06) | |

| Age | −11,220.28 | −8465.78 | −10,099.94 | −3.57+ | −5.19* | −6429.26 | −6506.11 | −6667.13 | −5985.53 |

| (−1.30) | (−0.87) | (−0.89) | (−1.93) | (−2.36) | (−0.75) | (−0.67) | (−0.58) | (−0.51) | |

| NarrRich | 56,992.23* | 38,051.70 | 51,169.98 | −10.77+ | −10.14 | 61,769.72⁎⁎ | 43,957.28 | 57,878.34 | 56,307.45 |

| (2.38) | (1.33) | (1.40) | (−1.97) | (−1.43) | (2.63) | (1.53) | (1.58) | (1.48) | |

| NarrDur | 12,190.47+ | 12,256.31 | 14,517.50 | −1.61 | −2.32 | 13,623.56* | 13,141.24+ | 16,052.62+ | 17,969.17+ |

| (1.93) | (1.64) | (1.56) | (−1.13) | (−1.28) | (2.20) | (1.76) | (1.72) | (1.85) | |

| Certif | 546,098.08** | 556,658.52⁎⁎ | 624,250.70* | −43.49 | −74.52 | 588,989.56⁎⁎⁎ | 580,514.13⁎⁎ | 673,568.73⁎⁎ | 734,971.15⁎⁎ |

| (3.18) | (2.78) | (2.51) | (−1.13) | (−1.54) | (3.49) | (2.90) | (2.70) | (2.87) | |

| DocNarr | 65,286.30⁎⁎ | 18.91⁎⁎⁎ | 54,915.63* | 47,396.54+ | |||||

| (3.25) | (4.91) | (2.59) | (1.81) | ||||||

| FictNarr | 110,133.67⁎⁎ | 16.38* | 99,295.03* | 82,594.29+ | |||||

| (2.66) | (2.04) | (2.38) | (1.92) | ||||||

| SSoM | 1113.86⁎⁎⁎ | 548.48 | 661.79 | 391.02 | |||||

| (3.47) | (1.51) | (1.64) | (0.91) | ||||||

| Constants | 136,923.59 | −1.45e+05 | −1.92e+05 | 267.26* | 426.95⁎⁎ | −2.20e+05 | −2.92e+05 | −4.75e+05 | −7.82e+05 |

| (0.30) | (−0.26) | (−0.27) | (2.48) | (3.06) | (−0.48) | (−0.51) | (−0.65) | (−1.03) | |

| N | 279 | 213 | 168 | 213 | 168 | 279 | 213 | 168 | 161 |

| R2 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.16 |

| adj. R2 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.12 |

| F | 5.15 | 4.56 | 3.76 | 6.43 | 2.89 | 6.47 | 4.26 | 3.64 | 3.68 |

t statistics in parentheses

Then, we tested the mediating effect of the shared sense of meaningfulness using Baron and Kenny's (1986) three-step methodology. Model 3 was used to test the relationship between the mediator and dependent variables. According to Table 3, shared sense of meaningfulness had a positive impact on attentional resources (β3 = 1113.9, p3 < 0.001). H3 was therefore supported. Next, we tested the relationship between documentary narrative and fictional narrative using shared sense of meaningfulness as the dependent variable. According to the results for models 4 and 5, documentary narrative and fictional narrative have a positive impact on shared sense of meaningfulness (β4 = 18.91, p4 < 0.001; β5 = 16.38, p5 < 0.05). H2a and H2b are supported. We added the explanatory variables documentary narrative and fictional narrative, as well as the mediating variable, shared sense of meaningfulness, to the regression model, using attentional resources as the dependent variable. According to the results in models 6 and 7, the relationship between shared sense of meaningfulness and attentional resources was not significant; thus, we used the bootstrap method to verify the mediating effect.

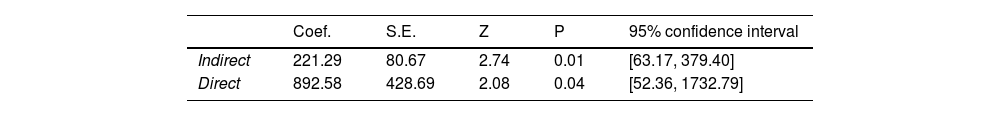

To test the mediating effect of H4, we followed Cheung, Xiao and Liu (2014) to apply the bootstrapping technique (the sample size was set at 1000). Table 4 depicts a formal test of the indirect (mediating) effect. It shows that the indirect effect of documentary narrative on attentional resources through shared sense of meaningfulness, controlling for age, gender, certification, narrative richness, and narrative duration, had a point estimate of 304.598 (95% BCa) and was statistically significant (p <0.05). It can be seen that the 95% confidence interval does not contain 0 for the indirect effect (5.900, 603.295). Hence, the direct effect of the mediating variable is not significant when the total effect is significant (H1a). This suggests a fully mediated effect of shared sense of meaningfulness on documentary narratives and attentional resources. However, the mediating effect of shared sense of meaningfulness on fictional narratives and attentional resources has not been validated. Therefore, H4 was only partially confirmed.

Robustness testAlternative measurementTo verify the reliability of the empirical results, we replaced the measures of the dependent and independent variables and repeated the OLS regressions.

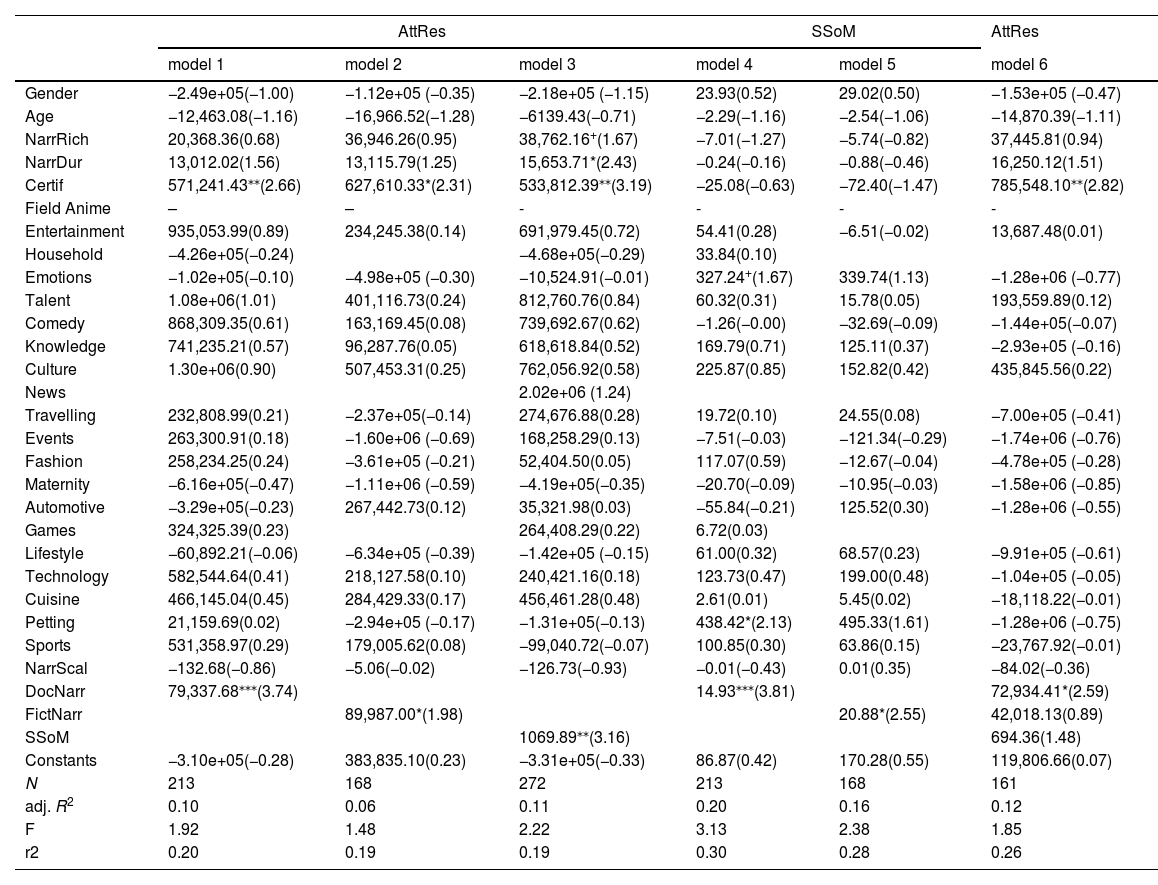

First, we substituted the measure of the independent variable with manual identification. We invited three PhDs in linguistics as experts to classify the narrative style of the short videos. Later, we explained to the experts the connotations of fictional and documentary narratives in digital entrepreneurship narratives based on the relevant research advances on fictional narratives by Pizer (1971) and Bradbury and Guadagno (2020) and documentary narratives by Lou and Yuan (2019). The experts then assessed the vloggers’ short-video styles and counted the number of videos with documentary narratives and fictional narratives as the two independent variables measured. The expert determination process was decided according to the principle of minority rule. Table 5 reports the results of the model tests after changing the independent variable measures. Models 1 to 3 illustrate that documentary narrative, fictional narrative, and sense of shared meaning can still positively influence the acquisition of attentional resources even when the independent variable digital narrative is changed as a measure (β1=104,249.3, p1<0.001; β2=89,818.6, p2 <0.001; β3=1113.9, p3 < 0.001). H1a, H1b and H3 were supported. Both documentary narratives and storytelling narratives promoted the formation of shared meanings between audiences and entrepreneurs (coef. 13.81, p < 0.01; coef. 10.02, p < 0.05), and H2a and H2b were supported. Furthermore, we used the non-parametric percentile bootstrap method to iteratively sample the data to obtain more accurate parameter estimates. The results are presented in Table 6. The 95% confidence intervals for the Bia-correction for the indirect effect of documentary narrative on attentional resources through a sense of shared meaning were [63.17218, 379.4039], respectively, excluding 0, indicating that a sense of shared meaning in documentary narrative and attentional resources plays a mediating role, which partially supports H4.

Robustness test results——Alternative measurement and Expanding the variable window period.

Second, we measured attentional resources by replacing followers with the number of comments on a short video. Comments reflect the audience's immersive engagement with short-video content and can effectively describe the video's appeal. Table 5 reports the results of model testing after replacing the dependent variable measure. Model 7 shows that documentary narrative and shared sense of meaning still promote access to attentional resources after changing the dependent variable measure of attentional resources (coef. 12,389.9, p < 0.001; coef. 272.00, p < 0.001). Thus, H1a and H3 are supported. However, the effect of story narrative on attentional resources was no longer significant after the number of comments was used as a measure of attentional resources. This may be due to the fact that in the entrepreneurial narratives of social entrepreneurs, audiences attribute more emphasis to the authenticity of the content and experience. Thus, fictional narratives show a limited motivation to engage compared to documentary narratives.

Expanding the variable window periodConsidering that it takes some time from the release of short videos to the acquisition of attentional resources, we expanded the number of short-video variables collected from 10 to 20 short-video samples per vlogger to further improve the robustness of the results of the model runs. The regression results are presented in Table 5 Model 11 to Model 16, where H1a, H2a and H3 are supported.

Addition of control variablesControl variables were also added. These were the industry sector and the total number of videos posted by the entrepreneurs. Based on the platform's classification criteria, the industry fields were included in 20 categories, such as field, anime, entertainment, household, emotions, talent, and so on. The test results are shown in Table 7, with the supported H1a, H1b, H2a, H2b, and H3.

Robustness test results——Addition of control variables.

To improve the robustness of the model estimation results, we expanded the sample scale based on the existing sample, increasing the samples from 304 to 3082. However, the number of vloggers’ hashtags and ages were no longer published and were replaced with IP addresses due to a change in the categories displayed in the information on the Kwai platform. Therefore, the control variables were replaced by the region to which they belonged. The results in Table 8 show that H1a, H1b, H2a, H2b, and H3 are still validated.

Robustness test results——Increase the sample size.

Digital entrepreneurial narratives have realized the integration of multi-media such as video, image, and sound with textual language, presenting users with new scenarios of authenticity and immersion and bringing great impact to the theory and practice of social entrepreneurial legitimacy. Focusing on how changes in narratives driven by digital entrepreneurial narratives affect the attentional resources of social entrepreneurship, we applied a textual analysis approach to study data from over 300 social entrepreneurs on Kwai, China's first short-form video platform. We drew the following conclusions. First, the interactive and localized characteristics of digital technology support documentary narrative to record and reveal genuine social issues and responses and then develop the significance of social entrepreneurship. In turn, documentary narrative gains the recognition and attention of the audience. Second, fictional narrative implies that the virtual and cross-media properties of digital technology enable constructed and organized stories through the application of multiple media and then convey the relevance of social entrepreneurship through vivid metaphor. Consequently, it draws the audience's interest and attention. Third, the building of shared meaning is a crucial technique for social entrepreneurship to gather attentional resources through documentary narrative. The documentary narrative presents a real, immersive scene for the audience, evoking real emotions in the user and triggering reflection and engagement. It is a process of shared meaning construction. Yet, shared sense of meaning fails to mediate the impact between fictional narratives and attentional resources. This may be because in social entrepreneurship, documentary narratives better enable audiences to visibly and by immersion perceive the authenticity of social meaning and social values, while fictional narratives more stimulate users’ curiosity and interest to engage and are not yet significant for meaningful reflection. This also highlights the uniqueness of social entrepreneurship.

Theoretical and practical implicationsImplications for entrepreneurial narrativeWe contextualize entrepreneurial narrative research by highlighting the interactive nature of entrepreneurial narratives and its implications for social entrepreneurship (Lounsbury, Gehman & Ann Glynn, 2019). According to our study, documentary narratives can foster empathy and local identification, resulting in both cognitive and affective engagement and recognition of social entrepreneurship among audiences. These results support the necessity of presenting authentic evidence in specific contexts, as emphasized by Allen and Preiss (1997). In order to compensate for a weak legitimacy foundation and provide the audience with an immersive experience, social entrepreneurship requires the provision of more real information about the social entrepreneurs and their entrepreneurial processes, unlike traditional business entrepreneurship. Moreover, fictional narratives transcend the confines of conventional entrepreneurial narrative approaches, and they are able to attract a wide range of audiences through lively and entertaining stories that showcase the common and distinctive values of entrepreneurs.

Compared to typical business narratives, social entrepreneurship narratives within the digital domain allow and align with entrepreneurs who use storytelling to evoke emotional resonance among audiences and construct social meaning, as well as concretize abstract social values and entrepreneurial concepts to better convey their value propositions. The results of our study indicate that both documentary and fictional narratives extend the boundaries of traditional entrepreneurial narratives, leading to a gradual shift from rational strategies to a cognitive and emotional process of shared sensemaking. It is important to note that this may have significant implications for social entrepreneurship, as entrepreneurs are encouraged to think more deeply about the substance of social value and how to communicate it to the public. The narrative strategies of social entrepreneurs can also be judiciously chosen based on the situation. More precisely, fictional digital narratives can make abstract concepts more accessible and relatable through interactive storytelling, multi-media integration, and virtual or augmented reality. These elements provide an immersive environment that fosters a deeper connection with the values and ideas presented. Allegories, metaphors, and character development within digital narratives can inspire empathy and motivate the audience to support the social entrepreneur's cause. On the other hand, digital documentation of social entrepreneurship projects can effectively showcase tangible impacts and real-life examples. Interactive maps and timelines provide a comprehensive understanding of the initiatives’ scope and progress, while data visualization and infographics simplify complex information, making it accessible to a broader audience. Video and audio content, such as interviews and testimonials, create an authentic and personal connection, humanizing the issues being addressed. Overall, our study contributes to the formalisation of social entrepreneurship and provides practical implications for entrepreneurs seeking to create social value through storytelling.

Implications for legitimacy of social entrepreneurshipConsidering the existing research on social entrepreneurship legitimacy, our study adopts a unique perspective by emphasizing the role of attentional resources as a manifestation of legitimacy in the digital era. Previous research has highlighted the importance of attentional resources as indicators of legitimacy across various contexts (e.g., Kibler, Salmivaara, Stenholm & Terjesen, 2018; Ruebottom, 2013). By focusing on attentional resources, our study contributes to a deeper understanding of the legitimacy and impact of social entrepreneurship. Building on this premise, our research suggests that attentional resources reflect both the value of social identity and the willingness of the public to engage with social entrepreneurship. In this context, social entrepreneurs aim to acquire attentional resources through effective digital storytelling, which relies on advanced technologies such as 5G communication and CDN (Content Delivery Network). This approach employs a dualistic strategy that combines documentary and fictional narratives to shape a new vision for social innovation. In acknowledging the link between attentional resources, social identity, and audience engagement, our study expands the understanding of social entrepreneurship legitimacy. Additionally, digital technology challenges the traditional binary opposition between legitimacy and uniqueness in entrepreneurial narratives by enabling vast connections and strong audience interaction. Even unconventional fiction narratives can contribute to building legitimacy for social entrepreneurship by capturing attentional resources.

In conclusion, our study offers insights into the complex and dynamic nature of social entrepreneurship legitimacy in the digital age. It underscores the significance of attentional resources and digital storytelling in shaping audience perceptions and engagement with social entrepreneurship. By examining the interplay between attentional resources, social identity, and digital narrative strategies, our research provides valuable guidance for social entrepreneurs seeking to enhance their legitimacy and impact in an increasingly interconnected world.

Implications for sensemaking of social entrepreneurshipThis study aims to provide a deeper analysis and discussion of social entrepreneurship's relevance by emphasizing its social sensemaking. The study builds on the research of Kimmitt and Muñoz (2018) and Sabbaghi and Cavanagh (2018) and provides a deeper understanding of the role of social meaning construction in the sensemaking process of social entrepreneurship. As we argue, social entrepreneurship is fundamentally a sensemaking process, in which social entrepreneurs use digital entrepreneurial narratives to express, sense-make, and sense-give their self-worth. As a result of these narratives, social groups are provided with shared meaning and are able to achieve greater dissemination of social value. Instead of focusing on the process of sensemaking for entrepreneurs and their businesses, social entrepreneurship aims to expand social value by incorporating stakeholder interests into the sensemaking process. As a result of these narratives, social groups can gain a greater sense of belonging and be able to disseminate social value more widely. As they engage in collaborative communication and value creation, social entrepreneurs and audiences generate socially recognizable values that are shared by both parties.

We contribute to the field of social entrepreneurship sensemaking research by highlighting the importance of social meaning construction, which can be achieved through communication and co-creation of value between social entrepreneurs and their audiences. In this way, the study of the value of social entrepreneurship is extended, enabling us to gain a deeper understanding of how social entrepreneurs generate social value and how they can effectively communicate this value to their audiences. Additionally, our study offers a theoretical basis for understanding social entrepreneurship in digital contexts. By exploring the role of attentional resources and digital storytelling in shaping legitimacy, we provide a foundation for future research on the unique challenges and opportunities faced by social entrepreneurs in the digital age. Social entrepreneurs should be aware of the differences in social entrepreneurship sensemaking and choose between developing entrepreneur-centered central sensemaking and user-centered distributed sensemaking based on the characteristics of the project, stage, audience profile, and other factors.

Implications for sense-giving of social entrepreneurshipWe contribute to the growing body of research on sense-giving and sensemaking in social entrepreneurship (e.g., Kimmitt & Muñoz, 2018; Sabbaghi & Cavanagh, 2018). Our argument is that the digital entrepreneurial narrative is an effective tool for integrating sensemaking and sense-giving into social entrepreneurship. This study differs from established entrepreneurship research, which generally views sensemaking and sense-giving as sequential and cyclical processes (Dutta & Thornhill, 2014). As a result of our research, we have found that sense-giving and sensemaking are not two separate and complementary concepts but are instead closely integrated and synergistic processes within the context of digital entrepreneurial narratives. By engaging in simultaneous communication with audiences through the interactive nature of digital entrepreneurial narratives, social entrepreneurs and audiences are able to develop meaning and feedback loops that refine and strengthen the sense of identity and mission of the social entrepreneur. As a result, our study contributes to the current understanding of sense-giving research by highlighting the importance of considering the interdependence between sensemaking and sense-giving in digital entrepreneurial narratives. Furthermore, this provides new significance-enhancing ideas for social entrepreneurs in the digital space. Social entrepreneurs are capable of integrating sense-giving into sensemaking and can iteratively sense-make by instantaneously drawing feedback from the sense-giving process.

Limitations and directions for future researchFirst, this study is limited in its ability to make causal inferences due to the cross-sectional nature of the research design. Due to the limitation of data availability, we currently only have access to data based on a certain time period. However, the effect of entrepreneurial narratives influenced by digital technology is dynamic and variable. Therefore, the use of panel data in future studies would be a better means to explore the mechanism of digital narratives on the acquisition of attentional resources for social entrepreneurship. Second, the sample size of the data also has an impact on the accuracy of the study results. Since both digital entrepreneurship narratives and social entrepreneurship activities are new and promising concepts and practices in China, the eligible sample size is small. However, this does not detract from the importance of exploring this trend. Future research needs to broaden the sources of data and sample size to explore the impact mechanisms of digital entrepreneurship narratives at various industry levels of social entrepreneurship certification. Third, because digital entrepreneurship narratives are a new concept, there is no clear way to measure them. Therefore, this paper is a new attempt at measuring documentary and fictional narratives using a combination of text analysis and machine learning to construct a variable lexicon. Future research can improve the accuracy of exploring machine learning methods for variable measurement. Finally, this paper proposes the mechanism of the role of documentary and virtual narratives in digital entrepreneurship narratives for social entrepreneurship in terms of the content form of entrepreneurship narratives. Whereas entrepreneurial narratives contain richer content, future research can continue to explore the impact of digital technologies on the relationship between entrepreneurial narrative identity, schema, rhetoric, framing, and logic.

Authors are grateful for the financial support from Chinese National Social Science Foundation: The behavior and process management of social entrepreneurship enabled by digital technology (Project number: 20AGL008)