This study utilizes survey data from 248 high-tech enterprises in China’s Yangtze River Delta and employs hierarchical regression and bootstrap mediation analysis to investigate the mediating role of organizational learning (i.e., competence exploration and competence exploitation) in the relation between proactive/reactive corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate sustainability performance (CSP). Results reveal a dual mediation mechanism: proactive CSR enhances CSP primarily by fostering competence exploration (e.g., innovation and novel capability development, β = 0.27, p < 0.01), whereas reactive CSR improves CSP mainly through competence exploitation (e.g., refinement of existing capabilities, β = 0.24, p < 0.01). These findings indicate that the CSR–CSP link is not monolithic but depends on strategic orientation, which activates distinct organizational learning processes. By empirically identifying organizational learning as a key mediator, this research advances the corporate sustainability literature and challenges homogeneous interpretations of CSR’s impact. Furthermore, it provides novel insights regarding the nuanced effects of proactive versus reactive CSR, clarifying their distinct roles in shaping exploration and exploitation dynamics. This study not only refines theoretical understanding of the CSR–CSP linkages but also offers practical guidance for firms aiming to align CSR strategies with sustainability goals through targeted organizational learning processes.

The growing societal emphasis on environmental and social challenges has elevated corporate sustainability to the forefront of contemporary business practices and academic inquiry (García Martín & Herrero, 2020; Hristov & Searcy, 2025). Corporate sustainability performance (CSP) reflects a firm’s ability to balance environmental, social, and economic demands (Bansal, 2005; Gerged et al., 2025). Yet, despite corporate social responsibility (CSR) being a key driver of CSP (Chang, 2015), their linking mechanism remains under-explored.

Extant research, which is grounded in the institutional theory, effectively explains CSR's role in building external legitimacy (Kramer & Porter, 2006; Scott, 2013). However, this externally focused view treats CSR largely as a symbolic signal, creating a crucial gap: it fails to explain how CSR is translated into performance inside the firm, or why firms with similar CSR investments achieve divergent CSP outcomes (Archel et al., 2011; Luo & Bhattacharya, 2009). This underscores the need to complement the external perspective with a focus on internal legitimacy and capability building (Deephouse, 2009).

Studies have usefully distinguished between proactive CSR (voluntary, value-driven initiatives) and reactive CSR (compliance-driven responses to pressure) (Chang, 2015; Maignan & Ferrell, 2001). However, research has yet to systematically clarify the distinct internal pathways through which these strategies influence CSP. The theoretical link between these CSR orientations and the organizational learning (OL) processes that ultimately drive sustainable performance remain vague.

The OL theory offers a perspective to address this issue by focusing on the dual processes of competence exploration and exploitation (March, 1991). We theorize that proactive and reactive CSR activate these learning modes differentially. Proactive CSR, owing to its long-term orientation and voluntary nature, cultivates psychological safety (Edmondson, 2010) that encourages experimentation and risk-taking, thereby fostering competence exploration (Atuahene-Gima, 2005). In contrast, reactive CSR, driven by short-term crises and regulatory pressures, prioritizes immediate efficiency and damage control, naturally channeling efforts toward competence exploitation (David et al., 2011; Galbreath, 2017). Against this backdrop, this study addresses the following research question: What are the divergent mediating pathways through which proactive and reactive CSR affect CSP, via OL (i.e., competence exploration and exploitation)?

This research makes two key contributions. First, it challenges the homogeneous, externally-focused interpretation of CSR's impact by introducing a dual legitimacy and capability-building framework. It transcends the established view of CSR as an external signal (Archel et al., 2011; Kramer & Porter, 2006) to demonstrate how it builds internal legitimacy and transforms internal capabilities through OL, thereby offering a more complete explanation for how CSR leads to CSP. Second, it provides a nuanced exploration of the mediating pathways that previous studies have merely glossed over. This study extends Chang's (2015) work on proactive/reactive CSR by moving from direct effects to a mediated model. Furthermore, it extends the research by Khan and Riaz (2023) by demonstrating that OL is not a unified mediator; rather, it theoretically distinguishes and empirically tests the differential roles of exploration and exploitation. This study's main contribution is the empirical confirmation of two divergent pathways: proactive CSR enhances CSP primarily by driving competence exploration, whereas reactive CSR does so primarily by promoting competence exploitation.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews theories and develops hypotheses. Section 3 discusses the sample and research method. Findings are presented in Section 4. Section 5 discusses the results, outlines theoretical, and practical implications, and acknowledges limitations and future research directions.

Theory and hypothesesTheoretical foundations: CSR, legitimacy, and OLConceptualizing proactive and reactive CSRCSR entails integrating social and environmental concerns into business operations and stakeholder interactions, while pursuing economic objectives (Turker, 2009). Moving beyond broad conceptualizations (e.g., Carroll, 1979, 1991; Wood, 2010), contemporary research emphasizes strategic distinctions, most notably between proactive and reactive CSR (Chang, 2015; Maignan & Ferrell, 2001).

Proactive CSR comprises voluntary, self-initiated actions driven by long-term ethical values, aimed at pre-emptively addressing societal and environmental issues (Mochales & Blanch, 2022). It is characterized by a progressive, value-driven orientation. For instance, in the context of China’s Yangtze River Delta high-tech firms, proactive CSR may entail investing in carbon-neutral chip production technologies ahead of regulatory mandates. In contrast, reactive CSR refers to compliance-driven responses triggered by external legitimacy pressures, such as regulatory threats or legitimacy crises, and is primarily focused on short-term damage control (Groza et al., 2011; Wei et al., 2012). Examples include revising battery production processes after receiving environmental non-compliance warnings. This strategic distinction aligns with the institutional theory, which posits that proactive CSR reflects normative (value-based) and cognitive (voluntary) compliance, while reactive CSR responds primarily to regulative pressures (Scott, 2013). Ultimately, their divergent temporal orientations (long-term vs. short-term) and primary motivations (value-driven vs. compliance-driven) are theorized to activate distinct internal organizational processes.

The CSR-CSP link: external legitimacy vs. internal capability buildingThe relation between CSR and CSP has been theorized based on two complementary but incomplete perspectives. The institutional theory perspective explains CSR adoption as a quest for external legitimacy, where firms signal conformity to regulatory and societal expectations to secure stakeholder support (Kramer & Porter, 2006; Scott, 2013). Although this perspective effectively explains why firms engage in CSR activities, it largely overlooks the internal processes that translate commitments into performance (Archel et al., 2011). Conversely, the resource-based view (RBV) shifts focus to internal capability building, positing that CSR’s impact hinges on developing valuable, rare, and inimitable competencies (Khan & Riaz, 2023). This view provides an intuitive, high-level alignment, which connects proactive CSR with long-term capability building and reactive CSR with short-term optimization, but does not define the process through which these strategies differentially shape capabilities.

This theoretical divide creates a puzzle; it fails to explain why firms with similar CSR investments frequently achieve divergent CSP outcomes (Luo & Bhattacharya, 2009). The institutional view explains the motivation but not the execution, while the RBV emphasizes the importance of capabilities but not their development process. Collectively, they indicate a common missing link: the internal organizational processes that bridge strategic CSR commitments and sustainable performance. Elucidating this “how” requires a theoretical lens focused on the dynamics of internal knowledge and capability development.

OL dynamics: exploration and ExploitationThe OL theory provides the necessary foundation to address this gap by focusing on the micro-level processes of knowledge development. As outlined in the Introduction, we posit that the pivotal link lies in how proactive and reactive CSR, through their distinct temporal orientations and impacts on psychological safety, shape firms’ engagement with the OL theory’s foundational duality: competence exploration (the pursuit of new knowledge and capabilities through experimentation) and competence exploitation (the refinement and extension of existing capabilities for efficiency) (March 1991).

We propose that proactive and reactive CSR predispose firms toward these distinct learning modes by influencing the organization’s temporal orientation and psychological context. Proactive CSR, with its inherent long-term orientation (Choi et al., 2023; David et al., 2011), fosters a culture of psychological safety (Edmondson, 2010) where employees are encouraged to experiment and tolerate failures as part of learning. This cognitive–behavioral context is ideally suited for high-risk, novel capability development, thereby activating competence exploration.

Conversely, reactive CSR is defined as a short-term orientation, driven by the urgency to resolve crises and comply with regulations (Wei et al., 2012). This pressure-filled context diminishes psychological safety, directing organizational attention and resources toward maximizing the efficiency and reliability of proven methods. This naturally channels efforts into competence exploitation.

Thus, the integration of temporal orientation and psychological safety theories reveals a coherent logic: CSR strategy influences the organizational context, which in turn activates the specific learning mode, namely, exploration or exploitation, through which sustainability performance is ultimately enhanced.

Research gaps and theoretical rationale for hypothesesThe preceding analysis reveals two interconnected theoretical gaps that this study aims to address. First, while existing theories elucidate the why (institutional legitimacy) and the what (internal capabilities) of the CSR–CSP link, they do not adequately explore the internal processes through which CSR commitments transform into performance. Second, although the distinction between proactive and reactive CSR is established, their differential pathways to performance via distinct OL modes remain theoretically presumed but empirically unverified.

As synthesized in Table 1, studies have either treated OL as a unified construct, ignored the distinction between CSR types, or focused solely on direct effects. Thus, the nuanced mediating roles of competence exploration and exploitation in the proactive/reactive CSR–CSP relation constitute a crucial, untested domain.

Literature Related to CSR and Our Study.

| Type of CSR | Key Findings and Mediator | Gap | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proactive and Reactive | Direct effects on green innovation | Lacks analysis of exploration/exploitation as mediating paths | Chang (2015) |

| General | CSR as symbolic signaling | Ignores internal OL dynamics linking CSR to CSP | Archel et al. (2011) |

| General | CSR drives incremental innovation | Does not distinguish proactive/reactive CSR or learning modes | Wei et al. (2012) |

| General | OL as a mediator between CSR and firm performance | Fails to differentiate proactive vs. reactive CSR; does not distinguish exploration from exploitation | Khan, S. N. and Riaz, Z. (2023) |

| Reactive CSR (regulatory pressure-driven) | Regulatory pressures promote competence exploitation to improve efficiency | Focuses only on reactive CSR and exploitation; ignores proactive CSR and exploration dynamics | Liu, Q., Yu, L., Yan, G. and Guo, Y. (2023) |

| Proactive and Reactive | Exploration and exploitation as mediators | Integrates external legitimacy and internal OL; clarifies differential effects of proactive/reactive CSR on both learning modes | Our study |

Building on this foundation and the theoretical framework developed in Sections 2.1.1–2.1.3, we posit that competence exploration and exploitation constitute the pivotal mechanisms that address the aforementioned gaps. To empirically test this proposition, we develop hypotheses that examine: (1) Whether competence exploration and exploitation mediate the CSR–CSP relation; (2) Whether proactive CSR has a stronger effect on fostering exploration, while reactive CSR more effectively promotes exploitation; and (3) How these dual learning pathways collectively bridge external CSR strategies with internal sustainability performance.

Mediating effect of competence explorationWe posit that both proactive and reactive CSR can foster competence exploration, albeit driven by distinct logics, which in turn enhances CSP. Proactive CSR cultivates an organizational context inherently conducive to exploration. Its voluntary and long-term orientation fosters a culture of psychological safety and tolerance for failure, empowering employees to experiment with novel practices and solutions (Edmondson, 2010; McWilliams & Siegel, 2011). Furthermore, by strategically engaging with diverse external stakeholders (e.g., research institutions, NGOs), proactive firms open channels for influx of new knowledge and perspectives, directly fueling the acquisition of new capabilities essential for exploration (Luo & Du, 2015; Shu et al., 2016). Thus, the very nature of proactive CSR institutionalizes the conditions for exploration.

Reactive CSR, while typically associated with exploitation, can also trigger exploration under specific circumstances. When experiencing a legitimacy crisis or unexpected regulatory pressure, a firm may discover that its existing knowledge base is inadequate to address the novel challenges at hand (Fortis et al., 2018; Murray & Vogel, 1997). This necessity forces the firm to urgently seek new knowledge and skills, often by forging new stakeholder connections (e.g., with legal experts or PR firms) to regain legitimacy (Zimmerman & Zeitz, 2002). In this context, exploration is not a strategic choice but a compelled response to a knowledge gap exposed by a crisis.

Ultimately, competence exploration enhances CSP by enabling firms to continuously integrate cutting-edge sustainable practices, develop innovative green technologies, and more deeply understand evolving stakeholder expectations across environmental, social, and economic dimensions (Atuahene-Gima, 2005; Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008).

Therefore, we hypothesize that competence exploration serves as a mediating mechanism for both types of CSR:

H1a.Competence exploration mediates the positive relationship between proactive CSR and CSP.

H1b.Competence exploration mediates the positive relationship between reactive CSR and CSP.

Mediating effect of competence exploitationWe argue that competence exploitation serves as another key mediator for both proactive and reactive CSR, channeling their effects toward CSP through a focus on efficiency and refinement. Proactive CSR promotes competence exploitation through its strategic and systematic nature. The explicit, long-term objectives inherent in proactive CSR provide a framework for firms to identify and purposefully refine areas where their existing capabilities can be enhanced to better achieve these goals (Torugsa et al., 2013). Moreover, the extensive stakeholder engagement typical of proactive CSR exposes the firm to diverse demands and best practices, inspiring incremental improvements and optimization within its current knowledge base to create greater value (Luo & Du, 2015).

Reactive CSR, by its very design, is a powerful driver of competence exploitation. The urgency to address crises and comply with regulations compels firms to deploy their most reliable and efficient competencies for immediate solutions (Groza et al., 2011; Wagner et al., 2009). This process often necessitates a thorough evaluation and subsequent fine-tuning of current operations to address deficiencies, thereby directly activating and promoting competence exploitation.

The link from competence exploitation to CSP is robust. By honing existing processes, exploitation directly enhances operational efficiency and minimizes resource waste, boosting both economic and environmental performance (Yang & Li, 2011). It also fosters the incremental innovations in products and processes that are essential for continuous improvement in corporate sustainability (Benner & Tushman, 2003). This relentless refinement enables firms to more reliably and efficiently meet market and societal expectations, thereby improving their sustainability performance (Lichtenthaler, 2009). Therefore, we hypothesize as follows:

H2a. Competence exploitation mediates the positive relationship between proactive CSR and CSP

H2b. Competence exploitation mediates the positive relationship between reactive CSR and CSP

Impact of proactive and reactive CSR on competence explorationPrevious CSR research has shown that proactive and reactive CSR can have different effects on company performance (Becker-Olsen et al., 2006; Chan et al., 2022; Chang, 2015; Groza et al., 2011; Marín et al., 2012). However, their effect on OL remains under-explored. This study investigates the independent impact of proactive and reactive CSR on competence exploration and exploitation through comparative analysis. Previous research suggests proactive CSR typically involves a long-term plan aligned with the company’s strategic goals (Bocquet et al., 2017). Meanwhile, companies that engage in reactive CSR are compelled to respond to challenges or stakeholder pressures as soon as they emerge, resulting in an emphasis on short-term outcomes (Buysse & Verbeke, 2003; Wei et al., 2012).

Companies that adopt proactive CSR are often engaged in developing radical innovation and tend to position themselves as industry leaders (Atuahene-Gima, 2005; Chang, 2015; Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2011). In contrast, companies that adopt reactive CSR strategies tend to engage in incremental innovation in product development and business operations and tend to adopt a follower strategy in terms of technologies, products, and business models (Chang, 2015; March 1991). Companies that adopt reactive CSR usually have a lower risk tolerance; thus, they hold a more conservative attitude toward exploratory activities compared to companies that adopt proactive CSR (Atuahene-Gima, 2005).

In summary, proactive CSR tends to facilitate a longer-term orientation and a greater tolerance for risk than reactive CSR. Given the characteristics of competence exploration, where its value realization occurs over an extended period and results experience significant uncertainty, this study posits that proactive CSR can facilitate competence exploration more effectively than reactive CSR. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H3.The positive impact of proactive CSR on facilitating competence exploration is stronger than that of reactive CSR.

Impact of proactive and reactive CSR on competence exploitationReactive CSR aims to promptly address CSR crises to mitigate damage to the company’s reputation (Groza et al., 2011; Wei et al., 2012). The unpredictability of crises and the urgency of their resolution compel companies adopting reactive CSR to prioritize utilizing their established competence to address crises. Companies that adopt reactive CSR usually have a lower risk tolerance compared with those that adopt proactive CSR (Atuahene-Gima, 2005). Competence exploitation, which is characterized by brief periods of value realization and predictable outcomes, better aligns with the risk attitude of companies adopting reactive CSR.

Based on the above analysis, this study posits that reactive CSR can facilitate competence exploitation more effectively than proactive CSR. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H4.The positive impact of reactive CSR on facilitating competence exploitation is stronger than that of proactive CSR.

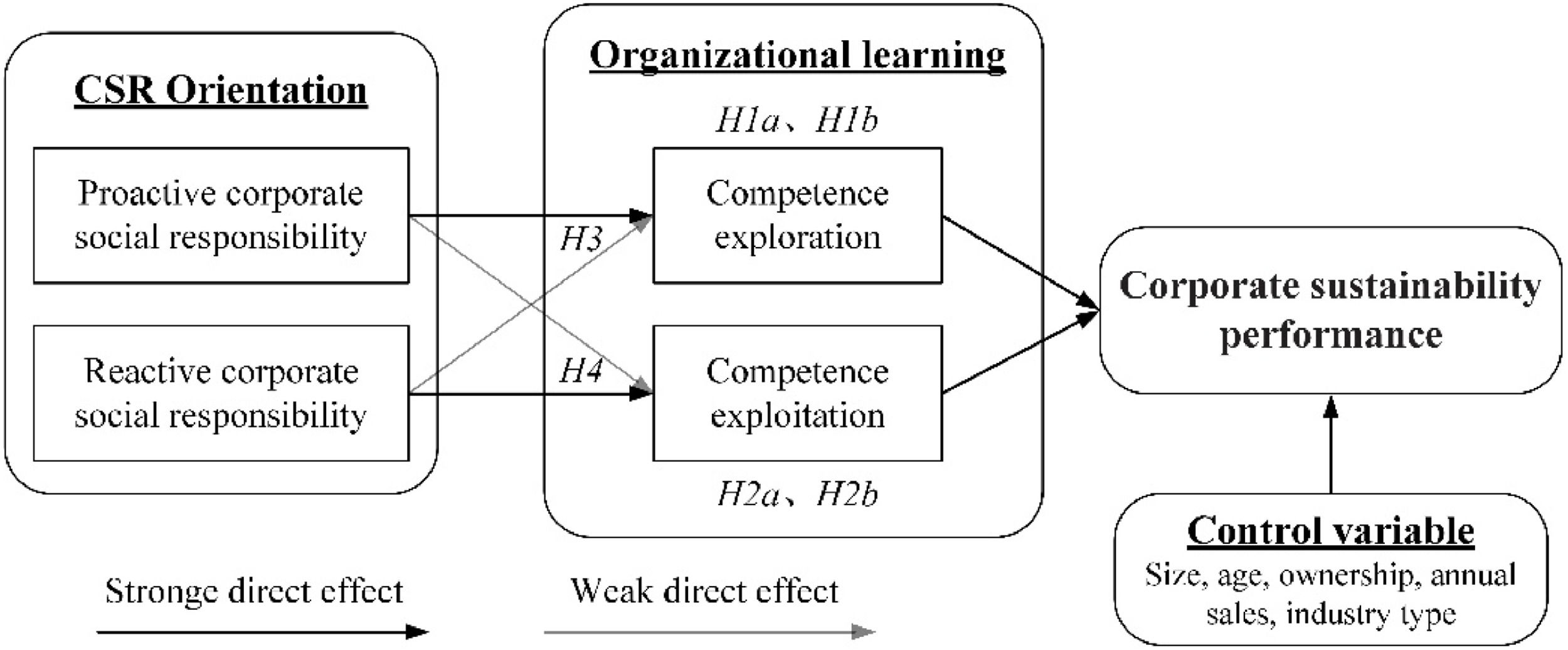

Fig. 1 illustrates the theoretical model, where H1a/H1b propose competence exploration mediates the relationship between proactive/reactive CSR and CSP; H2a/H2b propose competence exploitation as a mediator; H3/H4 hypothesize proactive CSR has a stronger effect on exploration, and reactive CSR has a stronger effect on exploitation.

Research methodSample selectionWe adopted a random sampling approach to select a representative sample of high-technology enterprises situated within the Yangtze River Delta region. This region is distinguished by its substantial economic expansion in recent decades. However, it also experiences significant environmental pollution due to its extensive industrial activities in the past. The pollution led to a governmental response in 2014, termed the “war on pollution,” highlighting the urgency of environmental improvement. Consequently, companies in this area are required to adhere to strict environmental regulations (Steinz et al., 2016), which renders it an ideal setting for this study.

We adhered to a four-phase process as suggested by Gerbing and Anderson (1988) to ensure the reliability and validity of the questionnaire. The first phase involves creating a questionnaire based on well-established research that has been previously tested and validated in similar research contexts. During the second phase, experts in strategy and innovation, along with managers, were consulted to refine the questionnaire design, providing critical feedback to enhance its readability and relevance. The data collection proceeded in two key phases during 2024. The third phase (preliminary study) was conducted in March 2024 in the Hefei High-Tech Zone to test validity, followed by the fourth phase (full-scale survey) administered to enterprises in the Yangtze River Delta region from June to August 2024. This timing aligns with the regional industrial context, as it followed the 2024 policy updates on environmental regulations in the Yangtze River Delta, ensuring relevance to current CSR practices.

Data were collected through an anonymous online survey of senior managers from companies in the Yangtze River Delta National Industrial Park; the survey was facilitated by the park’s management committee. The average tenure of the respondents was 4.1 years and they were familiar with their firm’s CSR, learning, and sustainability performance. After receiving the questionnaire feedback, we reviewed the responses to verify their validity. From 462 distributed questionnaires, 301 were returned. After screening, 248 valid responses were retained for analysis. Non-response bias was assessed by comparing the sales, ages, and shareholder attributes of the companies that responded with those that did not. A comparison between early and later respondents was also conducted. The results indicate that non-response bias is not significant in our study. Table 2 presents detailed information about the sample profile.

Sample demographic (N = 248).

Note: Data collected from March to August 2024, with preliminary testing in March and full-scale survey during June–August.

Abbreviations: %, percentage; N, number of observations. Source: Created by the author.

All key variables were measured using well-established scales on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree/very low” to 5 = “strongly agree/very high”), adapted to the context of high-tech firms in China. It is noteworthy that our measures rely on self-reported data from managers, which may introduce potential biases such as social desirability. To address these concerns, we implemented several procedural remedies during the survey design phase (Podsakoff et al., 2003): (1) ensuring respondent anonymity; (2) engaging experts and senior managers to review questionnaire items for clarity and objectivity; and (3) employing distinct scale formats for different constructs. As reported in Section 3.4, statistical tests confirmed that common method bias is not a significant concern.

Corporate sustainability performance (CSP) was measured as a reflective construct capturing three dimensions: economic prosperity, social equality, and environmental integrity (Bansal, 2005). Following Xie and Zhu (2020), we applied a four-item scale that assessed the firm’s achievement in (1) reducing hazardous waste and emissions, (2) conserving resources, (3) achieving profit growth, and (4) satisfying public and governmental expectations.

Proactive and Reactive CSR were measured as distinct constructs using scales adapted from Maignan and Ferrell (2001) and Chang (2015). To enhance validity, each construct integrated both attitudinal indicators (capturing managerial intentions) and behavioral indicators (reflecting tangible actions). Specifically:

Proactive CSR was operationalized with three attitudinal items (e.g., “Our firm views proactive CSR as a core strategic priority…”) and two behavioral items (e.g., “Our firm actively engages with the public through voluntary initiatives…”).

Reactive CSR was measured with two attitudinal items (e.g., “Our firm prioritizes resolving CSR-related crises promptly…”) and three behavioral items (e.g., “We engage with the public reactively… in response to controversies”).

Organizational Learning (Competence Exploration & Exploitation) was measured using five-item scales for each, following Atuahene-Gima (2005). Competence exploration items focused on the acquisition of new knowledge and capabilities (e.g., adopting innovative methods, integrating new technology). Competence exploitation items assessed the refinement of existing competencies (e.g., improving manufacturing processes, upgrading existing skills).

Control Variables: We included several firm-level variables that could influence CSP: firm size (Bernard et al., 2018), firm age (D'Amato & Falivena, 2020), annual sales (Mallin et al., 2013), ownership structure (Rong et al., 2017), and industry type (categorized into five sub-groups).

Reliability and validity of measurementsThe questionnaire settings were rigorously tested to ensure the validity of our research. An exploratory factor analysis, conducted using SPSS on the scale items, revealed factor loadings greater than 0.7, well above the 0.5 cutoff, indicating strong factor loadings. This analysis demonstrates that each latent construct has high internal consistency—Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) values exceed 0.7. Additionally, the average variance extracted (AVE) for all constructs surpassed 0.5, establishing convergent validity. A subsequent confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with AMOS further assessed the one-dimensionality of components and their convergent validity. All items significantly load on their intended latent constructs, with squared multiple correlations (SMCs) exceeding 0.3. The model fit indices (CMIN/DF=2.14, p < 0.01; CFI=0.89; TLI=0.88; IFI=0.89; RMSEA=0.07) underscore the model’s good convergent validity and reliability.

The validity of the measurements is tested using three methods. First, a comparison of the five-factor model with alternative models is conducted, wherein the five-factor model demonstrates superior performance. Second, following Gerbing and Anderson (1988), all constructs are tested in pairs, totaling 10 comparisons. These tests involve comparing an unconstrained model, where correlations are calculated without restrictions, against a constrained model, where correlations are fixed at 1. Statistically significant differences are identified between every pair, with a significant level of p < 0.05. Third, for all construct pairs, the squared intercorrelation is lower than the average variance extracted (AVE) values, further confirming the validity of the measurements.

Common method bias testsThis study adhered to the guidelines proposed by Podsakoff et al. (2003), which include drafting explicit survey questions and ensuring respondent anonymity to minimize socially desirable responses and mitigate common method bias (CMB). Distinct questionnaires are employed for different types of variables to mitigate the risks of CMB and endogeneity. Harman’s one-factor test reveals no single factor dominance, with the largest factor accounting for merely 13.9 % of the variance (Podsakoff et al., 2003), suggesting a minimal presence of CMB. CFA indicates a poor fit for a single-factor model (CMIN/DF=5.69; CFI=0.54; TLI=0.50; IFI=0.55; RMSEA=0.14), further reinforcing the absence of significant CMB. Introducing an artificial common method variable result in minor fit improvements (CMIN/DF=2.17; CFI=0.90; TLI=0.89; IFI=0.91; RMSEA=0.06), with changes less than 0.03. Additionally, employing the marker variable method (Lindell & Whitney, 2001), job experience is applied as a theoretically independent variable, exhibiting minimal correlation (r = 0.01 with reactive CSR), confirming the limited impact of CMB. Table 3 confirms that significance levels remain stable after adjustments, further supporting the minimal influence of CMB in this study.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix.

Notes:n = 248; correlations adjusted for common method appear above the diagonal, unadjusted below; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Abbreviations: S.D. standard deviation Source: Created by the author.

The first five variables are measured on a Likert 5-point scale, with minimum = 1 and maximum = 5.

To empirically investigate the proposed hypotheses, we employed a hierarchical regression approach following the logical steps of mediation analysis (Baron & Kenny, 1986), complemented by bootstrap testing for robustness. It is crucial to interpret the findings as revealing associations and mediating pathways consistent with our theoretical model, rather than definitive causal relationships, owing to the cross-sectional nature of our data. The analysis proceeded in three sequential steps:

Step 1: Testing the Baseline and Direct Associations on CSP

First, we estimated a baseline model to examine the direct association of CSR with CSP. A significant coefficient is a necessary preliminary condition for testing mediation.

CSP=α₀+α₁(Proactive CSR)+α₂(Reactive CSR)+Σαᵢ(Controls)+ε

Step 2: Testing the Association between CSR and the Mediator. This step examines whether the independent variables (CSR) are significantly associated with the hypothesized mediators. The result is presented in Table 4.

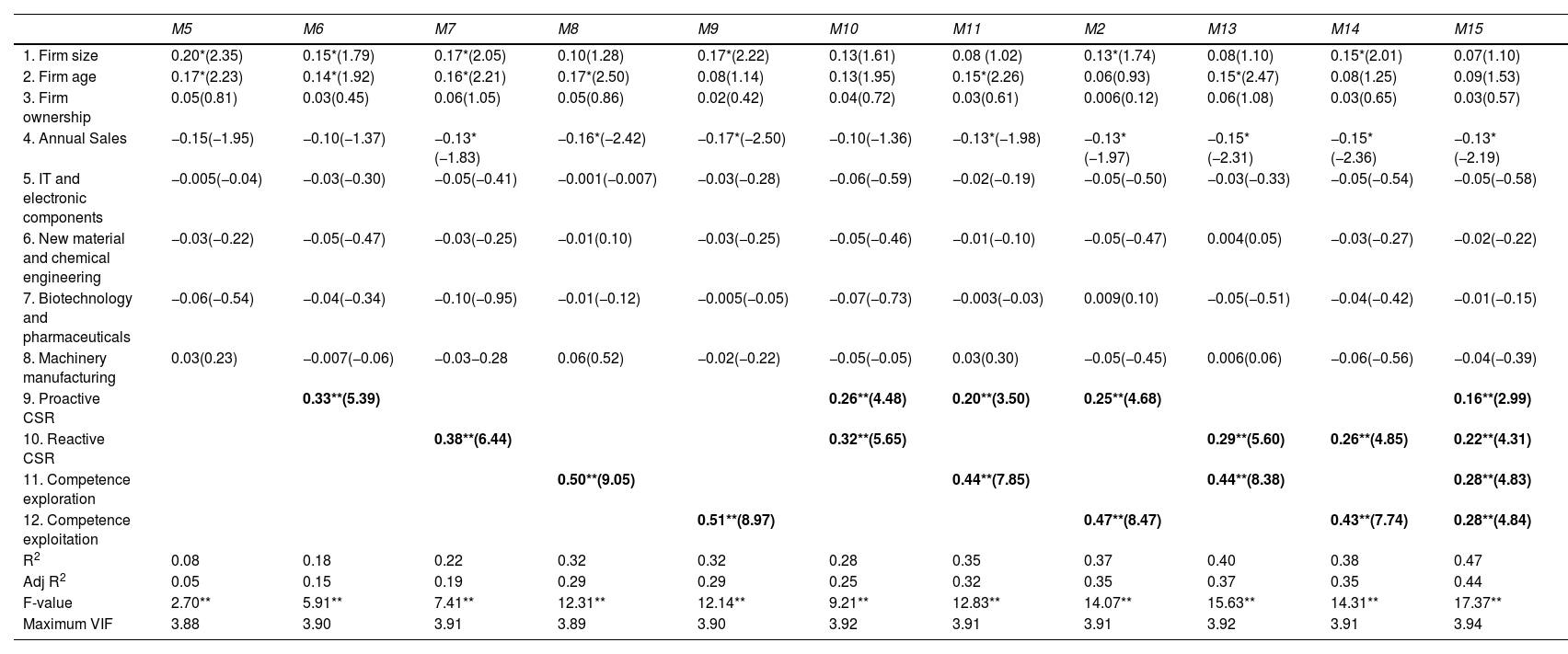

Regression results (DV: Competence exploration / Competence exploitation).

Note(s):n = 248; **p < 0.01. *p < 0.05, *p < 0.10; Reporting standardized coefficients and T-values in parenthesis.

Abbreviations: VIF, Variance Inflation Factor. Source: Created by the author.

Mediator = β₀ + β₁(Proactive CSR) + β₂(Reactive CSR) + Σ(Controls) + ε

Step 3: Testing the Mediation Effects. Here, we estimated a series of models to analyze the combined association of both CSR and the mediator with CSP. Evidence for mediation is supported if γ₃ (the path from the mediator to CSP) is significant and the magnitude of γ₁/γ₂ (the direct paths from CSR to CSP) is reduced compared to α₁/α₂ in Step 1. The results of steps 1 and 3 are presented in Table 5.

Regression results (DV: CSP).

Note(s):n = 248; **p < 0.01. *p < 0.05, *p < 0.10; Reporting standardized coefficients and T-values in parenthesis.

Source: Created by the author.

CSP = γ₀ + γ₁(Proactive CSR) + γ₂(Reactive CSR) + γ₃(Mediator) + Σγᵢ(Controls) + ν

ResultsThis section presents the empirical findings in a structured sequence to address the study’s hypotheses: first, foundational data diagnostics (descriptive statistics and multicollinearity checks) to validate analytical rigor; second, tests of comparative hypotheses (H3, H4) examining CSR’s differential effects on OL (competence exploration vs. exploitation); third, tests of mediation hypotheses (H1a, H1b, H2a, H2b) linking proactive/reactive CSR to CSP via OL; and finally, a synthesis of key results to consolidate empirical conclusions.

Foundational data diagnosticsDescriptive statistics and correlationsTable 3 presents the descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients for all variables. The correlation patterns provide preliminary support for our theoretical model. Both proactive CSR (r = 0.37, p < 0.01) and reactive CSR (r = 0.39, p < 0.01) are positively correlated with CSP. Similarly, competence exploration (r = 0.53, p < 0.01) and exploitation (r = 0.28, p < 0.01) are also positively correlated with CSP, aligning with our hypothesized relationships.

Multicollinearity checkAll independent and mediating variables were standardized prior to analysis to mitigate multicollinearity. The maximum variance inflation (VIF) factor across all models was 3.94—well below the conventional threshold of 10 (Neter et al., 1985). This confirmed that multicollinearity was not a significant concern.

Tests of comparative hypotheses (H3, H4)H3 and H4 propose differential effects of CSR types on OL: H3 predicts that proactive CSR exerts a stronger positive effect on competence exploration than reactive CSR, while H4 predicts that reactive CSR exerts a stronger positive effect on competence exploitation than proactive CSR. We tested these using regression models predicting competence exploration and exploitation (Table 4). Models 1 and 3 include only control variables, while Models 2 and 4 introduce proactive and reactive CSR.

Support for H3 (CSR and competence exploration)Model 2 (Table 4) shows that both proactive CSR (β = 0.27, p < 0.01) and reactive CSR (β = 0.13, p < 0.05) are positively associated with competence exploration. A T-test confirms that the effect of proactive CSR is significantly stronger (T = 2.14, p < 0.05). This finding supports H3: proactive CSR is more effective in fostering competence exploration than reactive CSR.

Support for H4 (CSR and competence exploitation)Model 4 (Table 4) reveals that reactive CSR has a stronger positive association with competence exploitation (β = 0.24, p < 0.01) than proactive CSR (β = 0.11, p < 0.1). A T-test confirms this difference is statistically significant (T = 2.37, p < 0.05). This result supports H4.

Tests of mediation hypotheses (H1a, H1b, H2a, H2b)We tested the mediating role of OL using the hierarchical regression steps outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986) and confirmed with robust bootstrap and Sobel tests (Zhao et al., 2010). The regression results for CSP are presented in Table 5 (regressions predicting CSP). The bootstrap mediation tests are summarized in Table 6.

Results of Sobel Tests and Bootstrapping for Mediating Effect.

Source: Created by the author.

The conditions for mediation are met:

CSR is associated with CSP (Models 6 & 7, Table 5: proactive β = 0.33; reactive β = 0.38, p < 0.01).

CSR is associated with the mediator, exploration (Model 2, Table 4).

Exploration is associated with CSP (Model 8, Table 5: β = 0.50, p < 0.01). When exploration is included (Models 11 & 13), the direct effects of CSR on CSP decrease, indicating partial mediation.

Bootstrap analysis (Table 6) provides robust confirmation:

H1a is supported: Proactive CSR → Exploration → CSP (Indirect effect β = 0.16, 95 % CI [0.08, 0.25], Sobel Z = 3.76, p < 0.01 (no zero in CI, confirming significance)).

H1b is supported: Reactive CSR → Exploration → CSP (Indirect effect β = 0.11, 95 % CI [0.03, 0.22], Sobel Z = 2.45, p < 0.01 (no zero in CI)).

Mediation via competence exploitation (H2a, H2b)Similarly, the conditions for exploitation mediation are met:

CSR is associated with the mediator, exploitation (Model 4, Table 4).

Exploitation is associated with CSP (Model 9, Table 5: β = 0.51, p < 0.01). When exploitation is included (Models 12 & 14), the direct effects of CSR on CSP decrease.

Bootstrap analysis (Table 6) confirms the effects:

H2a is supported: Proactive CSR → Exploitation → CSP (Indirect effect β = 0.09, 95 % CI [0.02, 0.18], Sobel Z = 2.31, p < 0.01).

H2b is supported: Reactive CSR → Exploitation → CSP (Indirect effect β = 0.15, 95 % CI [0.07, 0.26], Sobel Z = 3.14, p < 0.01).

Discussion and conclusionKey findingOur analysis of 248 high-tech firms reveals two distinct pathways linking CSR to CSP through OL. The results, discussed in Section 4, consistently support all hypotheses and can be synthesized as follows:

The Proactive CSR Pathway primarily enhances CSP by fostering competence exploration (Indirect effect β = 0.16), aligning with its long-term, innovation-oriented nature. Proactive CSR has a stronger effect on exploration (β = 0.27) than reactive CSR (β = 0.13).

The Reactive CSR Pathway primarily enhances CSP by promoting competence exploitation (Indirect effect β = 0.15), consistent with its short-term, efficiency-focused logic. Reactive CSR has a stronger effect on exploitation (β = 0.24) than proactive CSR (β = 0.11).

These robust findings confirm that OL is not a monolithic mediator but a dual mechanism, with the strategic orientation of CSR (proactive vs. reactive) activating divergent routes to sustainable performance.

Theoretical implicationsOur findings empirically demonstrate two distinct mediating pathways: proactive CSR enhances CSP by fostering competence exploration, whereas reactive CSR contributes to CSP primarily by promoting competence exploitation. First, we refine the understanding of proactive versus reactive CSR beyond the direct effects established by Chang (2015). While Chang focused on CSR’s direct impact on green innovation, our study clarifies the mediating mechanism of OL. We prove that proactive CSR’s long-term focus fosters exploration by institutionalizing tolerance for failure and risk-taking (Edmondson, 2010), whereas reactive CSR’s compliance imperative drives exploitation through refinement under short-term efficiency pressures. This discovery delineates the micro-foundational paths through which CSR influences innovation and sustainability, mirroring meta-analytic findings that link CSR types to distinct outcome domains (Vishwanathan et al., 2020) and Liu et al.’s (2023) evidence on exploitation gains from regulatory pressure.

Second, our findings challenge the dominant, externally-focused legitimacy perspectives (Archel et al., 2011; Kramer & Porter, 2006) by revealing how internal legitimacy, manifested via psychological safety and operational efficiency, is the critical enabling condition for CSR to translate into CSP. This internal capability-building view aligns with and extends Khan and Riaz’s (2023) work. While they established OL as a general mediator, we advance this by disaggregating the construct, demonstrating a one-to-one correspondence between CSR type and learning mode (proactive→exploration; reactive→exploitation), thereby resolving the limitation of treating OL as a unified mechanism.

Third, we diffuse a key tension in the organizational ambidexterity literature (March 1991; Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008) by identifying CSR strategy as an antecedent that determines a firm’s learning orientation. We demonstrate that CSR type, much like CEO incentives (Martin et al., 2016), acts as a powerful contextual factor that systematically sways the exploration–exploitation balance, directly extending behavioral strategy frameworks into the sustainability domain.

Practical implicationsOur findings provide managers with a diagnostic framework to strategically deploy CSR resources based on their firm’s specific context and objectives. The quantified pathways offer unambiguous priorities for resource allocation.

First, firms should prioritize CSR investments based on the dominant pathways revealed by our mediation analysis. Innovation-intensive enterprises (e.g., renewable energy) can prioritize proactive CSR to amplify competence exploration. Voluntary initiatives such as green R&D partnerships—consistent with our finding that proactive CSR boosts exploration by 27 %—foster psychological safety (Edmondson, 2010, 2014) and cross-functional experimentation. Regulation-heavy industries (e.g., manufacturing) can frame reactive CSR as a lever for competence exploitation. Post-audit actions (e.g., upgrading emission controls) should optimize existing processes, aligning with our result that reactive CSR enhances exploitation by 24 %.

Second, the strategic choice between these pathways should be further refined depending on the firm’s position. Start-ups and resource-constrained firms should initially focus on reactive CSR to build operational legitimacy and stability via exploitation. Industry leaders must champion proactive CSR to shape future markets and standards. A leading technology company, for instance, could launch an open-source platform for exploring new industry-wide solutions while solidifying its leadership role. Portfolio managers can apply this framework to diagnose business units. A traditional automotive parts business unit might require exploitation-led initiatives, while a new mobility solutions business unit would benefit from exploration-oriented mandates, enabling precise resource allocation. By treating CSR as a strategic lever for building specific capabilities, managers can systematically enhance their firm’s sustainability performance.

Limitations and future researchThis study has several limitations, which present opportunities for future research. First, the sample scope is confined to high-tech enterprises in China’s Yangtze River Delta region. This area is characterized by stringent environmental regulations and a high level of economic development. Consequently, the CSR motivations and practices of firms in this specific institutional context may significantly differ from those in regions with laxer regulations (e.g., inland China) or in non-high-tech sectors (e.g., traditional manufacturing). The observed relationships might be amplified by this unique context. Future studies should incorporate cross-regional and cross-industry samples to rigorously test the generalizability of our model.

Second, the cross-sectional research design, while revealing significant mediating pathways consistent with our theory, prohibits definitive causal claims. For instance, although we posit that “proactive CSR fosters competence exploration, which in turn enhances CSP,” the reverse causality—whereby high-performing firms are more inclined to invest in proactive CSR—cannot be dismissed. To establish causality, future research should employ longitudinal designs, such as multi-year (e.g., 3–5 years) panel datasets, or leverage quasi-natural experiments (e.g., environmental policy updates in the Yangtze River Delta) using difference-in-differences (DID) models.

Third, the measurement approach relies on managerial self-reports, which may be subject to perceptual biases. To enhance the robustness and objectivity of the findings, future research could triangulate our measures with archival data. Competence exploration could be assessed via patent counts or R&D intensity, while competence exploitation might be reflected in production efficiency metrics. Similarly, CSP could be complemented by third-party Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) ratings.

Statements and declarationsThe authors declare that they have no known competition financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. Some or all data, models, or code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72,002,001, 72,374,002, 72,532,004), the Guangdong Province Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning 2023 Discipline Co-construction Project (GD23XGL126), Guangzhou Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning 2025 Discipline Project (2025GZYB65) and the Anhui Social Science Innovation & Development Research Grant (2024CXQ527).

CRediT authorship contribution statementYingyu Wu: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Dujuan Huang: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Jiangfeng Ye: Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

The authors would like to thank the editors and reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.