National intellectual capital (NIC) has been of interest to scholars since the 1990s. Despite NIC research making up for less than five percent of the research on Intellectual Capital, it has become an important pillar of IC research tradition, extending the understanding about intangible capital and the dynamics of value creation from the organizational level to the level of broader ecosystems and nations. Special foci and interest in global intellectual capital are visible in modern NIC research. Interest in social, environmental, and economic responsibility within the research has increased. National competitiveness as a focus seems to be shifting toward a focus on sustainability and responsibility in the global context. New countries with universities engaging in active research and new types of intellectual capital have emerged. The definition of NIC has remained quite unchanged. This study builds on 142 academic articles on NIC, from the period 1991-2020, and presents an update to the stages of evolution of NIC literature.

This work studies National Intellectual Capital (NIC) as a concept, positions research around NIC within the broader field of intellectual capital (IC) research, and illustrates how the topics and the foci of academic NIC research in journal articles have developed and changed during the years. The analysis presented is based on a set of 142 identified and classified academic articles on NIC from between the years 1991-2020.

Research on Intellectual Capital can be divided into streams that concentrate on organizational (OIC), regional (RIC), national (NIC), and global (GIC) aspects of intellectual capital. Mainstream IC research is based on studying the organizational level. Pedro et al. (2018a, 2018b) estimate that the proportion of studies with an organizational focus is as high as 92.7%. Despite the clear dominance of organization-level studies, the number of articles published on National Intellectual Capital has also steadily increased in recent years. In the big picture, the proportion of NIC research of the overall research on intellectual capital is found to be (only) 1.1% (Orjala, 2021), while it has also been estimated to make 4% of the overall research (Pedro et al., 2018a, 2018b). Regional-level studies and IC research, on the global-level, both occupy a niche in the overall IC research scene. NIC research is a minor, but independent fiber within the whole of Intellectual Capital research.

We show how the quantity of NIC research articles has grown through the years and in which countries´ universities NIC research has been active. We also look at how the number of published articles and citations NIC research has received has developed. We identify three topical groups according to the main content of the article (target, measures and models, and policy) and four focal areas according to the methodology used, the article being general NIC, or concentrating on a specific niche issue.

The development stages of IC research presented previously in Pedro et al. (2018a, 2019b), until the year 2012, is presented, and the following period until 2020 is discussed. We propose an additional fifth stage to the IC research development framework based on the studied literature.

Following the example of the IC research development framework, we propose a framework for the development of NIC literature. The new NIC framework helps researchers in positioning their research and helps those interested in NIC research to gain knowledge about the development of the field.

To understand the field of national intellectual capital, it is important to understand what the concept is about and to define it. Furthermore, it is important to know what is included in national intellectual capital in terms of the different types of intellectual capital that it encompasses. The definition for NIC has not remarkably changed throughout the years (see Appendix A), and for the purposes of this research, we adopt the definition for national intellectual capital used in Orjala (2021): “the variety of intangible assets that give long-term advantages to a nation and interact with organizations, regions, or globally, and that are able to produce future and equal benefits measured at all levels.” NIC is seen as a basis for and an influencer, or enabler, of growth, value-creation, and/or a source of wealth, and is recognized as fuel for and a driver of future benefits (for a nation). We also stress dynamism and transformation as defining characteristics of NIC.

The conceptual framework of national intellectual capital consists of different types of core factors that can be classified as different capital resources. One of the first works on intellectual capital intangibles was by Edvinsson and Malone (1997); it was modified to be used in the national perspective by Bontis (2004). Bontis divided the intellectual capital of nations into human and structural capital. Structural capital was divided into market and organizational capital, and the latter was further divided into renewal and process capital (2004). Over the years, the variety and quantity of different capital-types increased and their content and relation to each other varied from researcher to researcher. Pedro et al. (2018a) clustered the many different capital types into three main types of intellectual capital: human capital, structural capital, and relational capital – the same trichotomy is used also by Massaro et al. (2020).

To this day, there is no consensus on a classification for the different types of intellectual capital among researchers. For example, it has been noted that “the content of intellectual capital and its different components remains quite vague” (Käpylä et al., 2012; see Radjenovic & Krstic, 2017). Recently scholars have expanded the concept of IC to ethical, social, and environmental issues (Ferreira & Fernandes, 2020), and to virtual (Vahanyan et al., 2018) and artificial capital (Bogoviz, 2020). This kind of transformation is reasonable, as the metrics used to measure NIC need to change over time to reflect the development of IC in a proper way (see Orjala, 2021). In the articles analyzed, 33 different types of (intellectual) capital are identified within the NIC framework. These different forms of capital are divided here into four capital baskets: IC focusing on the humans, on organizations, on external relations, and on what is, for the purposes of this research, called “new features” (see Table 1).

Different types of intellectual capital found in the studied literature.

Human-centered forms of intellectual capital dominate and are the most-often mentioned in NIC literature. The variety of capital types is the widest in the organization-centered types of IC. Digitalization is visible in the “new features” type of IC. In summary, NIC is a wide term that encompasses or at least can encompass many types of intellectual capital, although its distinctive features are a strong emphasis on dynamics and renewal capital.

The types of intellectual capital listed originally hail from the intellectual capital literature and refer to organization-level intellectual capital. When they are discussed and interpreted in the context of national intellectual capital, it should be done with care. It is possible to view some of the listed intellectual capital types as the “same as another listed type,” going deeply into the contents of what is specifically meant by each mentioned type; however, it falls beyond the scope of this research. In the case of “Virtual capital,” all types of virtual capital have been listed here under this umbrella term.

The types of intellectual capital listed originally hail from the intellectual capital literature and refer to organization-level intellectual capital. When they are discussed and interpreted in the context of national intellectual capital, it should be done with care. It is possible to view some of the listed intellectual capital types as “same as another listed type,” going deeply into the contents of what is specifically meant by each mentioned type; however, it falls beyond the scope of this research. In the case of “Virtual capital,” all types of virtual capital have been listed here under this umbrella term.

This paper continues as follows: In the next section, we analyze the development of NIC research through the studied literature in terms of quantity and geographics, and we analyze the topics and foci of research. We then present the stages that the general IC and NIC research have lived through and, inspired by the framework for the development of IC research, introduce a framework for the development of NIC. Based on the studied literature, we propose that the research on IC has also entered a new fifth stage. The paper is closed with a short summary section, and conclusions are drawn from the findings made. Some future directions for research are proposed and shortcomings of this work discussed.

Development of NIC research in published journal articlesIn this section, we look at a set of 142 academic articles identified to be relevant for NIC research, which represent just over one percent of the approximately 13,000 IC articles published during the studied period. We identify the development of quantity, the location of the main authors´ university, the topic, and the focus of the articles. The aim is to create a better understanding of the evolution of NIC literature published in academic journals and to show what research trends are found.

The methodology underlying the search and selection process used is the same as previously used in the literature (see Orjala, 2021). The studied period starts from the year 1991 and is based on pre-screening of the used databases that showed the first published journal articles on NIC research published during the second half of the 1990s (see Figure 1). For prudence, the searches were started from 1991, in order to not to leave out possible early contributions. The studied period ends at the year 2020. Only articles written in English were included. Four article databases were utilized in collecting the studied articles: Emerald Journals, EBSCO (all databases), Scopus Elsevier, and Science Direct. Depending on the database filters, “article,” “peer-reviewed,” and “scholarly” were used, where available. Articles related to Intellectual Capital at national or macro levels were included. Book chapters were not included.

The result of the already-filtered number of the initial abstract-level search was 1,327 articles. These articles were scanned, and exclusions were made, based on the article title pointing directly to predefined exclusion criteria with relation to the level of analysis (a firm, organization, region, university, research institute), i.e., clearly non-NIC research focus. The included set contains one article with a multi-level analysis, where, based on the authors´ judgment, the focus was also strong enough on NIC. Also, some other non-NIC-focused articles were excluded, such as purely technology-oriented articles and articles that concentrate on ethical issues.

The remaining 275 articles were (again) manually scanned by reading the abstracts, which resulted in a final total of 142 articles on NIC, of which to 131 we had full text access. The 142 articles were published in 80 different journals, the Journal of Intellectual Capital (JIC) being the single-most important source, with a 24.6% share of the NIC articles. All the articles selected were cross-checked with the Finnish Publication Forum (FPF) (www.julkaisufoorumi.fi/en) listing of high-quality academic publications, and 100 of the articles were rated at least level one (basic academic) according to the FPF. The rest of the articles were either journals below level one (not recognized as high quality) or conference articles. We used the Finnish system, as it is openly accessible and completely separate from the authors’ comprehensive quality rating of publication outlets. The FPF status of each studied article is visible in Appendix B.

For each article, the following information was extracted:

- 1.

Article type (“general NIC,” “country comparison,” “country analysis,” or “special NIC focus”) determined by a holistic overview of each article and based on the classification

- 2.

Main focus / research question (shortly)

- 3.

Database, where the article is stored (one of the four databases searched)

- 4.

Year of publication (1991 – 2020)

- 5.

Main topic of the article (“target,” “measures and models,” and “policy”; see Table 3)

- 6.

Geographical coverage (# of countries in the analysis)

- 7.

Number of citations the article had received by August 2021 and by March 2025 at Google Scholar

- 8.

Country of the university of the article’s main author

- 9.

Types of intellectual capital mentioned

A synthesis and analysis of the information collected from the selected articles give a holistic picture of the NIC literature from the selected point of view. The collected information (points 1-8 above) for the 142 articles studied is available in Appendix B.

First, we present the development of NIC literature and the geographical coverage of NIC research.

Development of NIC literature and country focusThe number of published academic NIC articles has been on an upwards-going trend during the studied period 1991–2020 (see Figure 1). Of the 80 journals, the Journal of Intellectual Capital (JIC) was the most dominant journal, with an almost 25% share (35 pcs.) of published articles, translating to approximately 4.5% of articles published in the JIC touching NIC (JIC published 770-800 articles between the years 2000-2020), see Table 1. Other pronounced journals in the NIC space include the International Journal of Learning and the Intellectual Capital (IJLIC), with a 4.2% share of the published NIC articles, Technological Forecasting and Social Change with 3.2%, and Research Policy with a 2.8% share of the published NIC articles. From previous studies, we know that the two top NIC journals are also top publishers of IC research in general, with JIC having a 23% and IJLIC a 6.5% share of published IC articles (Pedro et al., 2018a).

Previous conclusions that NIC studies have been published in only a small number of journals (Labra & Sánchez, 2013) no longer hold true, as the situation has changed quite recently. The growing number and variety of journals publishing NIC content indicates a widening, and perhaps a fragmentation, of the concepts used and the dimensions of the analysis concerning National Intellectual Capital. Such new dimensions include, e.g., sustainability issues. The change is also due to changes in the publishing priorities of journals (see Bamel et al., 2020).

When one looks at the quantity of published NIC-relevant articles by the location of the university from which the first author is from, one can see that universities from 24 countries contribute with more than one article, see Table 2. The most active countries are the USA, with 16, and Spain, with 13 published articles. Taiwan, Portugal, Finland, Poland, the UK, Australia, Canada, and Romania contribute with five or more articles. Universities from eight countries produced most of the articles after the year 2010. The growth in the number of articles from Eastern European universities is evident in the 2010s. Polish, Romanian, Russian, and Serbian universities have been productive in the NIC space in recent years. The above hints that interest in NIC research is growing in terms of the number and location of universities engaging in it.

Figure 2 shows a listing of the countries with the most publications relevant to NIC research, based on the location of the first author´s university. The total number of countries contributing academic research relevant to NIC is 47. In general, Southern Asia, including China, Africa, and South America are scarcely represented, see Figure 3.

This observation is in line with Dumay et al. (2015), who observe that universities in Europe and Australasia are the two primary locations for public sector IC research and that North- and South American, and Chinese universities, are underrepresented.

Universities in Great Britain, the USA, Canada, and Australia are among the most prolific publishers of NIC-relevant research. Here, we observe that our choice to include only English language research excludes the NIC articles that were written in other languages. Analysis of non-English NIC research is left outside the scope of this research.

We collected the number of citations received by the studied articles on two occasions, in August of 2021 and in March of 2025. We mention that the most cited of the studied articles (citations in 2021 / 2025) are Perry and Guthrie (2000) with 2312 / 2946 citations, Bontis (2004) with 952 / 1160 citations, Guthrie (2001) with 802 / 1002 citations, Zheng (2010) with 377/531 citations and Malhotra (2000) with 375/436 citations. We note that the listed most-cited articles focus mostly on intellectual capital topics but have some NIC content, and the most-cited article is a literature review. For a complete listing of citations by the studied articles, see Appendix B.

The median number of citations (2021 / 2025) an article has received is 16 / 29, and the median number of annual citations is 2.9. The accumulation of citations has not slowed down in recent years, and even the oldest articles are still getting new citations. This is an indication of a research community around NIC that is alive and well. Our choice to use Google Scholar to record the citations was based on the observation that none of the used databases (which also report citations in their own way) include all the articles in the set, and we wanted to have a uniform and open-source citation information source for all studied articles. See Figure 4 for information about the development of NIC article citations.

Of the articles, 36 / 22 percent have been quoted less than 10 times, and 22 / 22 percent of the articles have been quoted less than once per year; 54 / 40 articles have been quoted more than 50 times.

The most prolifically cited (2021 / 2025) literature review is the article by Petty and Guthrie (2000), with 2 312 / 2946 citations (110.1 / 117.8 per year) and review articles by Secundo et al. (2020) 56 / 335 citations (N/A / 67.0 per year), Dumay et al. (2015) 119 / 213 (19.8 / 21.3 per year), Pedro et al. (2018a) 85 / 197 (28.3 / 28.1 per year), and Labra and Sánchez (2013) 80 / 106 (10.0 / 8.8 per year).

Twenty scholars have been authors in more than one NIC article: Lönnqvist, Nevado, Serenko, and Tomé are active scholars in this research area. There seems to be a good deal of dialogue between scholars and cross-citations between NIC articles.

Topics and main foci of NIC ResearchNIC research tradition is abundant, with a diversity of research directions. To categorize the NIC literature, articles studied have been classified according to topics and main foci. Topics open the objectives of the articles by focusing on the motivation of the research, the methodological choices, and outputs. “The main topic” -category gives an answer to the following question: “What is the main content of the article?” The “Main focus” categorizes the content of research between country/multiple country focus and a more general NIC, or a more specific NIC focus. With these classifications, we refine the understanding of how research perspectives are divided in the studied literature. These categories have been developed by the authors based on screening the mass of the articles and are thus normative, as has been to choose to allocate a specific article to a specific category.

The main topics of the articles

National intellectual capital research is divided here into three groups, depending on what the main topic of the article is, see Table 3.

Main topic, motivation, and features found in NIC articles.

The first topic is “target”-motivated research on (national) value-creation and performance “targets,” that include improved competitiveness, wealth-creation, well-being, and sustainable development among others. The scope of the research is in the external effects of NIC. Research under this class is based on measurements, often at a national level, but also on country comparisons.

These articles rely heavily on data availability. In addition to objective, value-free and neutral targets, the target-driven measurements, may also have some disputed ideological or competitive features (see Käpylä, 2012).

The second topical group of research is “measures and models” and studies phenomena, analyses cause-effect relationships, dynamics, and correlations in value-creation processes. The scope of this type of research is in the internal and interconnected processes that are needed in value-creation. The weight of these articles is on methods and the scholars’ (own) models, and methodologies are introduced.

The third group of topical research we call “policy,” and it is motivated by policy actions and has a strategy-orientation. This type of research is often at a national or global level. Co-operation is multi-sectoral, for example, between the academic and the policy levels, or between the global and the national levels. Policy group research is tackling the challenge of how to perceive the national IC phenomenon in practice (see Salonius & Lönnqvist, 2012).

Of the NIC articles, 23% belong to the topical group “target,” 52% to the group “measures & models,” and 25% to the “policy” group. Research that combines features of target- and measures-and-models-driven articles are common within the articles studied. Features of all topics are typically present in all articles. According to the reviewed articles, the number of measures and models and policy-perspective articles has been growing during the years 2016-2020, while the number of “target” group articles seems to be declining, see Figure 5.

The main focus of the articles

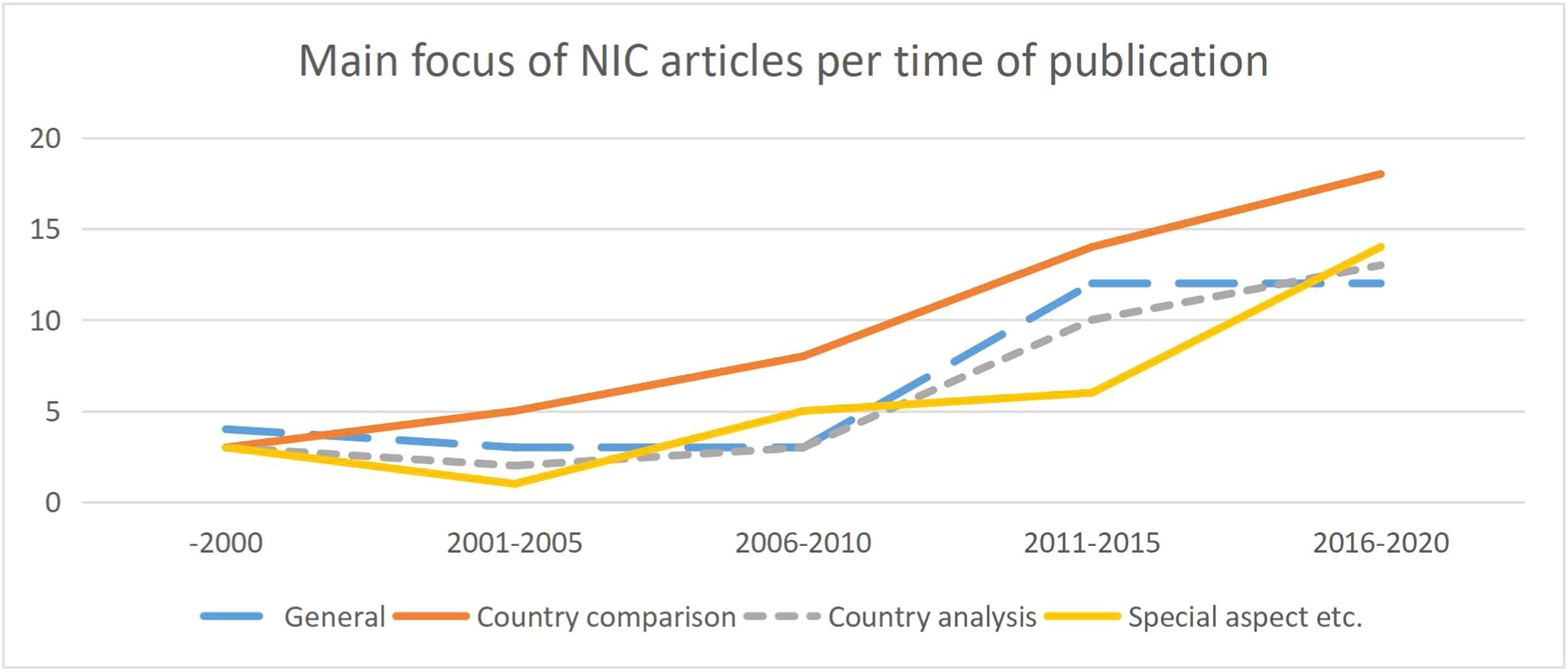

NIC articles have been divided here into four focal areas based on their main focus: “general,” “country comparison,” “country analysis,” and “special aspect” (e.g., environment, culture, crises). The articles may and often do include features from more than one focal area. In such cases, an article has been categorized according to the most pronounced focus (as seen by the authors).

Of the reviewed articles, 34% have the “country comparison” and 22% the “country analysis” focus, while the remaining 44% is divided between articles with a “general” (24%) and a “special aspect” (20%) focus. Of the articles with a focus on country studies, the share of single-country studies was 39%, while the rest were country comparisons (61%). In this sense, the situation has not changed from 2018, see Pedro et al. (2018a).

The articles of Bontis (2004, National Intellectual Capital Index: A United Nations Initiative for the Arab Region) and Lin and Edvinsson (2008, National intellectual capital: comparison of the Nordic countries) are good examples of NIC studies with a “country analysis” and “country comparison” focus.

When articles are analyzed by the date of publication and focus, it can be seen that the number of articles with a “special aspects” focus clearly increases after 2015. What is also clear is that the number of “country comparison” articles increases throughout the studied period. Within the “country comparison” focal area, there is a change from studying the determinants of competitive advantage toward the investigation of usable measures and models. Generally, there is an increase in the number of articles from all four focal areas, see Figure 6.

The Evolution of NIC Research – Five StagesWe combine the trends visible in the studied NIC-relevant research and propose a framework for the evolution of NIC research in terms of trends (topics studied) and foci from before the year 2000 until the year 2020, see the left column in Table 4. NIC research is a part of or niche within IC research, but it has an independent core, and it has had its own path of development. The proposed framework of the evolution of NIC literature is a novel construction. The proposed NIC framework is based on the 142 studied articles and is constructed in the same vein as the framework of development for intellectual capital, as presented in Pedro et al. (2018a, 2018b), see the right column in Table 4.

The trend during the first stage of NIC research (until the 2000) was to concentrate on issues of competitiveness and wealth creation in the global arena. The second-stage (2001-2005) trends include research into value analysis, intangibles, while the focus was on the development of methodology and concepts, including measurement of NIC and country comparisons. The third stage (2006-2010) included taking (processing) NIC methodology further and exploring the different types of intellectual capital in the NIC space. The focus was mostly on the countries with good data availability. The fourth stage (2011-2015) was characterized by consolidation of the NIC theoretical framework and development of measurement models. Growth of research was toward new countries and country comparisons. During the latest fifth stage (2016-) the focus has been on performance well-being and sustainability issues. New data sources have been taken into use. Overall, NIC research gained visibility in the more general IC research discussion. The number of universities engaged in NIC research has grown.

With regards to the intellectual capital framework, the first three stages of development were already presented in the early 2000s by Petty and Guthrie (2000), García-Ayuso (2003), Chatzkel (2006), Pew Tan et al. (2008) and Lin and Edvinsson (2020). They focus on organizational intellectual capital (OIC). These three stages show the transformation of research from a theoretical framework toward empirical proof and the use of IC in organizational management.

The fourth stage of intellectual capital research saw daylight in the taxonomy presented in 2018 by Pedro et al. (2018a, 2018b) and was based on earlier work by Borin and Donato (2013); Dumay and Garanina (2012, 2013); Guthrie et al. (2012); Labra and Sánchez (2013); and Roos and O’Connor (2015). This is the first stage to include research on national intellectual capital (NIC) and regional intellectual capital (RIC). The fourth stage is the last one in the taxonomy presented by Pedro et al. (2018a, 2018b) and according to them it started in 2004. In addition to focusing on the IC ecosystems of nations, the fourth stage focuses on IC in cities and regions.

As an addition to the original IC taxonomy framework, we propose, based on what we have learned from the NIC literature, a fifth research stage (starting from 2012) that captures the research trend into the social and global responsibility aspects of IC, see Table 5. The perspectives taken and the focus shift towards global intellectual capital is clearly identifiable (see, e.g., Bogoviz, 2020; Lee et al., 2017; Lin and Edvinsson, 2013; Lopes and Serrasqueiro, 2017; López and Navarro, 2012; Park and Oh, 2018; Pelle and Végh, 2015; Roos, 2017; Roth, 2020; Stachowicz-Stanusch, 2013; Stavropoulos, Wall and Xu, 2018; Vahanyan et al., 2018). In addition, the focus on social, environmental, and global responsibility seems to grow in IC research after 2012 (see Anghel et al., 2019; Cristea et al., 2020, MacGillivray, 2018). Matters pertaining to IC in civil society and the influence of third-sector actors on IC value-creation as gained attention (see Sharma et al., 2016). There seems to be a transformation from an interest in competitiveness toward sustainability and global responsibility (see Janković-Milić & Jovanović, 2019; Secundo et al., 2020).

Proposed fifth stage for the taxonomy framework of IC research.

The new proposed fifth stage of IC research is based on the analysis of the 142 NIC articles studied and, therefore, carries a strong NIC point of view. We note that also Massaro et al. concluded that “the relationship between IC and sustainability could benefit from a fifth stage of IC research” (Massaro et al., 2018). Dumay et al. (2020) found there to be a place or potential for a fifth stage of IC research in understanding how human, social, relational, cultural, and natural capital interact, when combined with knowledge experience and intellectual property, so that IC can be used to create economic, utility, social, and environmental value. Perhaps our proposition will further fuel the discussion about the need for adding a fifth stage to the IC research evolution framework.

From a data management point of view, the first four stages of IC research utilize data-sources in creating the measures of IC in a “stable” way, while in the fifth research stage, there are signs that data diversity, new data sources, and the importance of information capital will increase (see Orjala, 2021). We believe that, in the future, (N)IC research will be transformed by a wider use of data ecosystems that allow for more holistic analyses of NIC and IC issues.

Discussion and conclusionsThis article presents the results of an analysis that is based on reviewing 142 academic articles relevant to national intellectual capital research from between the years 1991 to 2020. The definition of national intellectual capital was discussed, based on the various definitions found in the studied literature, and it was noted that the definitions rarely changed throughout the decades – there seems to be a common core in the definitions. The definition of NIC is independent of what the topic and focus of research has been. This being the case with the definition of the NIC, the types of capital understood to be a part of NIC have changed, and today the types of intellectual capital NIC consists of are more numerous and varied in content than previously. Consequently, the same stands for the measures and models used to study and observe NIC. There is an emphasis on dynamics and renewal capital in NIC that is different from the enterprise level, as NIC studies the abilities of a nation to cope with change and development from the point of view of intellectual capital.

We analyzed the general features of the studied articles, including the geographical distribution of the universities of the first authors in NIC articles and trends in the number of articles published. We find that some of the countries from which the first NIC articles came from are no longer in the forefront of NIC research today. We also find that NIC research has been adopted by countries in Eastern and Southern Europe (e.g., Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Italy, Spain), especially in the form of country comparisons and single country studies in the 2010s.

We looked at the topics of NIC articles and divided the studied articles into three baskets. We find that measures-and-models-based research is the dominant research area within NIC. Policy-driven research has also been strong and it has grown. The action- and strategy-oriented research and research on how to perceive the (value of) NIC in practice, have recently gained in weight. NIC research is typically data-intensive, and country comparisons are a typical form of research. Research concentrating on a special or specific topic or aspect of NIC is growing, this is due to, e.g., the widening of the concept of NIC to include increasingly more types of intellectual capital and to each of them being suitable to be studied separately in the context of NIC.

The results show that NIC research tradition is also enriched by cross-disciplinary development in terms of, e.g., new data (big data), the technology and methods used to analyze data, and new metrics that consider less competitive aspects and more sustainability issues than ever before. We illustrated the evolution of NIC research by introducing a new NIC research development framework and presented it side by side with the previously presented evolution of IC research framework. In the NIC framework, we proposed an evolutionary path for NIC from before the year 2000 until the year 2020. The proposed NIC development framework is a new contribution.

Based on what we know about the development of NIC literature, and the development toward sustainability and social and global responsibility issues, we proposed that a fifth stage be added to the previously presented IC taxonomy framework that starts from 2012 and focuses on the sustainability and responsibility issues connected to IC in the global context. Studies in this fifth stage of IC research also reflect a focus on civil society and third-sector IC issues. We find and show that NIC research has its own independent development path and acknowledge that influence from prevalent IC research themes was clear in the early years of NIC research.

Making a comparison between the results shown here and the results that can be found in the previously published reviews, that include results relevant for NIC, would be observing that here we concentrate predominantly on national intellectual capital, while most previous work concentrates more broadly on intellectual capital. While the two (IC and NIC) walk in lockstep, this paper highlights the independent nature of NIC research.

We posit that NIC has a past, present, and a future of its own as a field of research, within the umbrella of IC research, and that it is meaningful to also consider, treat, and even study the development of NIC research separately from the development of overall IC research. This position is behind the notion of presenting the literature trends separately for NIC research, parallel to the trends of IC research, as was done here.

At the time of writing, generative artificial intelligence is high on the hype-curve, and there is a lot of discussion about the transformative power it may especially have on knowledge work. Automation of knowledge work through artificial intelligence also has a bearing on intellectual capital. The utilization level of national intellectual (data) capital, stored in the form of databases and digital libraries, may experience a jump. It remains to be seen, whether the saying “Data is the new oil” will make the nations with richer deposits of NIC in the form of data also richer in terms of economic growth and technical development through the utilization of generative artificial intelligence. In the future, we may study these issues also through the lens of studying the development of NIC research.

We want to point out some limitations to this work. Research on NIC is a niche within the otherwise quite abundant research on intellectual capital. This is to be taken into consideration when generalizing results beyond NIC research. When it comes to the proposed new fifth stage to the IC taxonomy, the results come from NIC research and the analysis of the reviewed articles; meaning that complementary work is still needed to fully understand the fifth development stage of the IC taxonomy. Therefore, our proposed fifth stage for (general) IC research is a proposal, not the full picture of IC development.

We note that the articles analyzed in this research have not been studied by using a multi-expert (inter-rater) method and the choice to include, or not include, an article was that of one of the authors. Some mainly (general) intellectual capital articles with importance to NIC have been included. Some of these are also among the list of the most-cited NIC-relevant articles. We refer the interested reader to see Appendix B for the complete citation information on the set of papers studied.

The three topic classes used have been determined by the authors, based on the studied articles; there may be a more objective way of creating a classification. While we have not identified any apparent biases, all research choices are those of the authors, as are any possible errors. A limitation that we point out is the non-inclusion of book chapters that may have left out relevant NIC research.

We find that future research opportunities within the area of NIC can be found in research that concentrates on new data sources, on new topical NIC questions, and on policy-related topics. Increasing the pool of countries included in comparisons would strengthen NIC research and our understanding of NIC in developing countries. Furthermore, looking at the nation-level ability to utilize artificial intelligence is interesting and will most likely be an important research avenue for NIC researchers in the coming years.

CRediT authorship contribution statementHannele Orjala: Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Mikael Collan: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis.