Ultra-high voltage (UHV) transmission projects are a cornerstone of China’s supply-side energy reforms, enhancing the national power system’s balance, efficiency, and resilience. Although their macroeconomic importance is widely recognized, evidence regarding how they affect corporate innovation remains limited. This study investigates the innovation effects of UHV deployment by exploiting its staggered rollout as a quasi-natural experiment. Using a difference-in-differences approach on a panel of Chinese listed firms from 2007 to 2023, we find that UHV deployment significantly boosts firm-level innovation output, increasing patent applications by 13.1 % on average. The effect is stronger in electricity-exporting provinces, central-western regions, areas with weaker grid capacity, and manufacturing firms. Thus, UHV yields higher innovation returns in structurally constrained environments. Mechanism analyses identify two key channels: alleviating financing constraints and facilitating digital transformation. UHV deployment also facilitates regional resource reallocation and supports corporate green transformation. By integrating energy infrastructure into the innovation literature, this study demonstrates that large-scale projects such as UHV serve not only as technical upgrades but also as strategic levers for innovation and sustainability. Overall, the findings offer actionable insights for developing economies seeking inclusive innovation-driven growth amid global green transition.

Innovation is widely recognized as a key driver of firm competitiveness and long-term growth (Porter, 1992; Solow, 1957). However, innovation is not frictionless. Firms often confront external barriers, among which energy availability and reliability pose fundamental yet frequently overlooked constraints (ABB, 2023; Guo et al., 2023). Despite rapid economic growth, structural limitations in energy distribution remain pervasive. In 2015, the United Nations underscored the urgency of addressing these challenges, defining Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7 as “access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy.” Global electricity demand is projected to grow by nearly 4 % annually through 2027 (IEA, 2025). However, grid connectivity continues to face persistent bottlenecks that undermine system reliability (Gorman et al., 2025). These challenges are particularly acute in developing economies, wherein insufficient energy infrastructure impedes firms’ capacity to invest, expand, and innovate—thereby widening the innovation gap (Foster et al., 2023).

Approximately 1.5 million kilometers of new transmission lines have been built worldwide over the last decade. However, inadequate transmission remains a critical constraint for power system expansion and energy security (IEA, 2025). China launched its ultra-high voltage (UHV) projects in 2006, with the first line commissioned in January 2009. Unlike generation or local grid upgrades, UHV is a system infrastructure that links resource-rich regions to major load centers, easing interregional bottlenecks (He et al., 2024). An unreliable power supply is often cited as one of the most detrimental input shortages, hindering firms’ growth and innovation potential (Bao et al., 2024). Issues such as supply volatility and transmission inefficiency heighten operational uncertainty and increase costs, discouraging long-term innovation investment (Shahin et al., 2023). Improving grid reliability and ensuring more predictable, scalable access to electricity may enable UHV deployment to foster sustained research and development (R&D) and technological upgrading (Madessa et al., 2024).

We draw on the resource-based view and conceptualize reliable power as a strategic, general-purpose input that enhances firms’ resource base and supports experimentation and knowledge creation (Barney, 1991). Moreover, real-options theory suggests that lower supply volatility reduces the downside risk of irreversible investment, and thus strengthens firms’ incentives to invest in R&D (Dixit & Pindyck, 1994). Recent studies provide supporting evidence. UHV deployment improves the spatial allocation and reliability of electricity, thereby expanding firms’ access to high-quality energy resources (Ren et al., 2025). In addition, UHV-supported hybrid systems enhance operational flexibility and reduce transmission uncertainty (Gou et al., 2024). Collectively, these findings suggest that stable and scalable energy infrastructure serves as a resource platform and an uncertainty-mitigation mechanism that fosters innovation. Accordingly, we pose the following question: Does UHV infrastructure deployment translate into measurable firm-level innovation gains?

Although a growing body of literature examines the economic and social impacts of infrastructure investment (Agarwal et al., 2023; Balboni, 2025), its innovation implications remain relatively underexplored. Studies have primarily focused on transportation (Andersson et al., 2023) and digital infrastructure (Du et al., 2024). Meanwhile, energy infrastructure has received relatively limited attention in the innovation literature. In advanced economies, energy infrastructure is often treated as background. However, in emerging and transition economies, unstable supply remains a major obstacle to firm expansion and innovation (Cole et al., 2018; Edeh et al., 2025). Engineering and systems research indicates that UHV enhances the stability and resilience of interregional transmission. By enabling more efficient delivery, it can lower marginal electricity costs (Gou et al., 2024; Ren et al., 2025). Nevertheless, despite rapid progress in UHV construction, firm-level causal evidence on whether and through which mechanisms such large-scale infrastructure promotes corporate innovation remains limited.

Recent studies on the socioeconomic effects of UHV have rapidly increased, highlighting both benefits and concerns. In terms of benefits, UHV investment expands electricity market capacity and generates multiplier effects, stimulating firm expansion and employment (Zhao et al., 2024). Furthermore, by improving system efficiency and enabling cleaner substitution, it yields environmental and productivity gains (Wang et al., 2023). However, regarding concerns, scholars caution that UHV may induce resource and revenue misallocation, exacerbate regional imbalances, and expose energy-rich but less-developed areas to “resource-curse” risks that hinder diversification (He et al., 2024; Sun & Min, 2024). This mixed evidence underscores the need for micro-level analysis to clarify how and under what conditions UHV affects corporate innovation.

Against this backdrop, we address three core questions. (i) Does UHV access enhance corporate innovation? (ii) If so, through which channels? (iii) Do these innovation effects exhibit systematic heterogeneity or coincide with progress in green transformation? Answering these questions can provide transferable evidence to guide the joint design of energy infrastructure investment and innovation policy in China and other developing economies.

We empirically examine these questions by utilizing the staggered rollout of China’s UHV transmission projects across provinces as a quasi-natural experiment. Using panel data on Chinese listed firms from 2007 to 2023, we implement a staggered difference-in-differences (DID) design to estimate the causal effects of UHV access on corporate innovation, measured by patent applications. UHV lines are the backbone of interprovincial corridors, whose high transmission capacity reshapes provincial electricity supply–demand balance, improves reliability, reduces energy costs, and mitigates production uncertainty. Collectively, these factors influence firms’ innovation incentives. Accordingly, for each province, we identify the commissioning year of its first connection to the UHV backbone and classify firm-years as treated once the province in which the firm is located is connected; otherwise, they serve as controls. Baseline estimates indicate that UHV access significantly increases corporate innovation.

We conduct several validation checks to ensure robustness, including parallel trend tests, placebo timing reassignments, propensity score matching (PSM) with DID regressions, and alternative innovation measures. We further employ an instrumental variable (IV) approach using the number of nature reserves as a routing constraint for provincial UHV access and exclude regions affected by the Low-Carbon City Pilot (LCCP) policy. The results remain stable across specifications, supporting causal interpretation.

The innovation effects of UHV deployment exhibit clear heterogeneity. The positive impact is stronger in electricity-exporting provinces, central-western regions, areas with weaker grid capacity, and manufacturing firms. Thus, UHV yields greater innovation returns in structurally constrained environments. Mechanism analyses further show that UHV promotes corporate innovation through two firm-level channels: alleviating financing constraints and facilitating digital transformation. Regionally, UHV facilitates more efficient resource allocation, as reflected in increased government R&D spending, accelerated fixed-asset investment, and enhanced human–capital accumulation, which collectively strengthen the foundations for innovation. Moreover, UHV deployment contributes to corporate green transformation, suggesting that energy infrastructure improvements can simultaneously enhance innovation and advance environmental sustainability.

Our study contributes to several research streams. First, we broaden the external perspective of innovation drivers. Extant research has primarily examined demand-side shocks (Fusillo et al., 2025; Trunschke et al., 2024) and broader business environment factors on the supply side (Fehder et al., 2025; Xie & Wang, 2025). However, relatively little attention has been paid to physical infrastructure, especially energy transmission systems, as a supply-side innovation enabler. Leveraging China’s staggered UHV deployment, we provide firm-level causal evidence that transmission infrastructure designed to ease imbalances in energy supply and demand fosters higher corporate innovation, thereby complementing this literature. Furthermore, extant studies emphasize internal firm attributes (e.g., managerial traits and organizational structure) or policy levers (e.g., intellectual property protection, taxation, and subsidies) as primary innovation determinants (Akcigit et al., 2022; Dai et al., 2025; Glaeser et al., 2023; Santoleri & Russo, 2025; Sunder et al., 2017). Meanwhile, we highlight a public infrastructure channel through which UHV reduces energy-related uncertainty and stabilizes the investment environment. This reveals a pathway beyond traditional firm-level or policy instruments through which the external operating context shapes innovative activity.

Second, we enrich the micro-level evidence on the economic impact of energy infrastructure. Prior studies have mainly focused on macro-level outcomes, such as carbon abatement, job creation, and regional development (Wang et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2024). However, we shift the focus to firm-level outcomes and demonstrate that UHV access significantly enhances innovation performance. Moreover, the heterogeneous patterns that we uncover, including stronger effects in electricity-exporting provinces, central-western regions, and areas with weaker grid capacity, suggest that infrastructure investment yields larger innovation returns under tighter baseline constraints (Foster et al., 2023). This evidence complements and refines macro-level understandings of how energy infrastructure contributes to inclusive and innovation-driven growth.

Finally, our findings offer transferable implications for energy infrastructure investment centered on UHV. Although comparative evidence suggests that public R&D and infrastructure spending jointly shape corporate innovation (Döme et al., 2025), most estimates are from advanced economies. However, many developing countries face binding fiscal and institutional constraints. Moreover, similar to China at an earlier stage, they contend with transmission bottlenecks and unreliable power supplies (IEA, 2023; Lavitt & Sargeant, 2025). Our firm-level evidence supports continued UHV deployment, and we recommend prioritizing interconnection and reliability upgrades in more constrained regions to achieve higher marginal innovation returns and guide inclusive transmission planning. For economies with limited fiscal space, phased and regionally targeted investment combined with diversified financing offers a practical pathway to unlock innovation potential by enhancing energy reliability (Cao, 2023; Lambe et al., 2024; Mangudhla et al., 2025).

Despite our identification strategy leveraging the quasi-exogenous rollout of UHV projects, several limitations remain. First, this analysis focuses on listed firms, which may not fully capture the dynamics of smaller enterprises. Second, although robustness checks and IV estimation enhance identification, unobserved regional shocks or concurrent policy interventions may bias estimates. Third, long-term effects may continue to evolve beyond our sample period. Future research could extend this analysis to non-listed firms, apply alternative identification strategies, and explore post-construction effects over longer horizons to assess the persistence of infrastructure-induced innovation.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature and presents the institutional background and hypotheses. Section 3 describes the data and empirical strategy. Section 4 reports the main results. Section 5 discusses further analyses. Finally, Section 6 presents the conclusions of this study.

Literature review and research hypothesesLiterature reviewDevelopment and growth theories underscore the central role of infrastructure in economic expansion and structural upgrading (Romer, 1990; Rostow, 1960). At the firm level, infrastructure raises private returns to R&D and rapidly translates ideas into outputs by reducing transaction costs, expanding the effective market size, and strengthening knowledge spillovers (Andersson et al., 2023; Du & Wang, 2024; Long & Yi, 2024). Corporate innovation relies on a stable supply of electricity, computing power, and logistics services; therefore, greater stability and predictability of these inputs will reduce disruption risk and extend firms’ planning horizons (Foster et al., 2023). Empirical research has examined transportation and digital infrastructure. New roads and highways expand market access and potential demand, boosting innovation output (Andersson et al., 2023; Long & Yi, 2024). Broadband upgrades reduce information frictions and enhance productivity, information technology adoption, and innovation speed and quality (Marinoni & Roche, 2025; Meng & Xu, 2025). Conversely, firm-level causal evidence on energy infrastructure, arguably the foundational layer enabling other systems, remains scarce.

Building on the resource-based view, electricity is a strategically valuable general-purpose input that supports competitive advantage by enabling experimentation and knowledge creation (Barney, 1991). Under the real-options framework, a more stable energy supply decreases the downside risk of irreversible R&D, thereby strengthening innovation incentives (Dixit & Pindyck, 1994). Empirical evidence shows that electricity costs and shortages significantly affect capacity utilization, digital adoption, and productivity. Outages particularly constrain firm performance in developing economies (Cole et al., 2018; Doan et al., 2025; Jia et al., 2023). Considering the capital-intensive, sunk-cost, and irreversible nature of large-scale energy infrastructure (Bennett, 2019), micro-level causal identification is essential for uncovering its innovation effects.

Most studies on energy infrastructure have focused on rural electrification or microgrids, emphasizing welfare and productivity gains rather than innovation outcomes (Lambe et al., 2024; Lewis & Severnini, 2020; Vidart, 2024). Technological attention has also been skewed toward “dirty” domains, such as fossil-fuel efficiency, that have more immediate returns (Stern & Valero, 2021). Consequently, the innovation implications of large-scale clean energy systems, particularly those capable of transforming regional energy access and industrial competitiveness, remain underexplored. Although a smaller but growing research strand has begun to examine how energy access relates to innovation outcomes (Trotter & Brophy, 2022), the findings remain fragmented and context-dependent. Moreover, research indicates heterogeneous marginal effects across infrastructure types (Shahbaz et al., 2021), implying that large-scale energy systems may affect innovation through complex and regionally conditioned channels that can be uniquely identified through micro-level analysis.

Macro-level studies highlight the contributions of China’s UHV system to carbon abatement, employment, and regional development (Wang et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2024). However, firm-level innovation evidence remains scarce. A few studies, such as Min and Wang (2025), use manufacturing data to show that UHV supports green transformation (proxied by environmental, social, and governance indicators) and explore mechanisms via co-invented patents. However, these analyses are sector-specific and largely descriptive, leaving unanswered questions regarding the causal mechanisms through which UHV affects firm-level innovation. Meanwhile, some scholars caution that UHV deployment may exacerbate regional disparities or “resource-curse” risks (He et al., 2024; Sun & Min, 2024), suggesting that the developmental impact of UHV may show substantial variation across regions and industries.

Collectively, these contrasting perspectives highlight a critical research gap. Despite UHV’s central role in China’s energy transition, systematic firm-level evidence on whether and through what channels such supply-side infrastructure shapes innovation remains limited. Addressing this gap is essential for evaluating the broader role of energy infrastructure in innovation-driven and sustainable growth. Accordingly, this study connects macro-level energy infrastructure investment with firm-level innovation performance by leveraging the staggered provincial rollout of China’s UHV backbone as a quasi-natural experiment. This approach enables us to uncover how external infrastructure environments shape firms’ innovation incentives and provide actionable insights for energy and innovation policies in developing economies. Thus, we offer novel firm-level evidence from the world’s largest and most integrated transmission network.

Institutional backgroundChina’s rapid industrialization and urbanization have fueled an explosive rise in electricity demand, particularly in the energy-intensive coastal and central provinces. However, the spatial distribution of energy resources remains highly imbalanced. Over three-quarters of coal and most hydropower resources are in northern and western China, whereas the majority of onshore wind and solar potential is concentrated in the northwest. In contrast, major load centers are situated thousands of kilometers away, with some exceeding 4000 km. This geographic mismatch between energy supply and demand has long posed a structural bottleneck in balancing national development.

This structural mismatch is not unique to China. Globally, electricity systems are facing similar challenges amid the energy transition. Grid expansion has lagged behind the rapid growth of renewable generation, leaving over 1600 GW of wind and solar capacity awaiting connection worldwide (IEA, 2025). Advanced economies have largely focused on upgrading aging grids and improving digital control systems. However, only China has achieved systematic nationwide deployment of UHV transmission. Considering its pivotal role in enhancing energy security, efficiency, and decarbonization, UHV has emerged as a strategic and high-end infrastructure technology, offering valuable lessons for emerging economies seeking to balance industrialization with clean energy transition.

China aimed to address these domestic and global challenges by elevating UHV transmission to a core national energy strategy in 2006. Defined as 1000 kV AC or ± 800 kV DC and above, UHV enables long-distance, high-capacity, and low-loss electricity transmission. Beyond its engineering significance, UHV plays a strategic role in addressing regional energy disparities, stabilizing electricity supply, and integrating renewable energy sources into the national grid. UHV reshapes firms’ production conditions by improving reliability and reducing supply volatility, thus creating an essential mechanism through which infrastructure can influence innovation incentives.

Following the pilot Jindongnan–Nanyang–Jingmen project in 2009, China expanded its UHV network through a centrally coordinated yet regionally staggered approval process. As of 2023, 39 UHV projects have been completed (Appendix Table 1), with a combined interprovincial transmission capacity exceeding 300 GW. These lines have delivered over 30 trillion kWh of electricity, reduced coal transport by more than 200 million tons annually, and cut cumulative carbon emissions by over 3.1 billion tons. The ±1100 kV Changji–Guquan line, a flagship project, spans 3300 km and transmits 12 GW on a single circuit, illustrating the technological scale and national coordination underlying UHV development.

Buoyed by these tangible achievements, UHV has solidified its position as a national development priority in recent years. It features prominently in China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025), with cumulative investments exceeding CNY 380 billion. Under the Belt and Road Initiative, UHV is also exported abroad, symbolizing China’s growing role in global infrastructure standard-setting. Additionally, UHV exemplifies the country’s state-led approach to infrastructure governance, reflecting its strategic importance in ensuring energy security, promoting regional coordination, and advancing the green transition. As a central pillar of China’s “new infrastructure” initiative, the UHV program provides a timely and policy-relevant context for examining how large-scale energy infrastructure shapes firm-level innovation outcomes.

Research hypothesesInfrastructure plays a foundational role in shaping corporate innovation by influencing input availability, cost structures, market access, and knowledge spillovers (Du & Wang, 2024; Ryan, 2021; Zhao & Dong, 2025). Among all forms of infrastructure, electricity is indispensable not only as a basic production input but also as the backbone of modern digital and industrial systems (Das & Mahalik, 2023). An unstable power supply increases operating costs, reduces capacity utilization, and compels firms to hold costly buffers (e.g., self-generation capacity and excess inventories), thereby crowding out resources for innovation (Bao et al., 2024; Fried & Lagakos, 2023). From a real-options perspective, uncertainty increases the value of waiting, shortens investment horizons, and discourages irreversible R&D (Bloom et al., 2007; Cho & Lee, 2021; Dixit & Pindyck, 1994). Empirical studies further show that electricity shortages and outages distort firm expectations, exacerbate financial and operational pressures, and inhibit innovation, particularly in developing economies (Doan et al., 2025; Jia et al., 2023).

UHV transmission offers a structural remedy. It enables long-distance, high-capacity, and low-loss electricity delivery to alleviate persistent regional supply–demand mismatches and materially improve system reliability and resilience (Xu et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2024). The resulting decrease in energy-related uncertainty improves cash-flow predictability and planning horizons, creating favorable conditions for long-term R&D (Brown et al., 2024). Stable and ample electricity also improves resource allocation and capacity utilization, freeing slack resources for innovation (Abeberese, 2017; Madessa et al., 2024; Xiao et al., 2022).

UHV projects generate broader ecosystem effects. They attract capital and skilled labor, foster industrial clustering, and cultivate an environment conducive to sustained innovation (Han et al., 2025; Moretti, 2021). By relieving firms of energy-related constraints and reinforcing regional innovation ecosystems, UHV not only secures production but also strengthens incentives to pursue innovation-driven upgrading. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1 UHV significantly enhances corporate innovation.

Financing constraints remain a key bottleneck in corporate innovation (Liu & Zhao, 2024). Financial institutions often struggle to assess the true value of R&D activities because of their high risk, uncertainty, and long payback horizons. This exacerbates information asymmetries and limits firms’ access to external capital (Czarnitzki & Giebel, 2024; Hall & Lerner, 2010; Hottenrott & Peters, 2012). Extant research consistently shows that financing frictions significantly depress firms’ R&D investment and innovation output, whereas easing these barriers can substantially enhance innovation performance (Liu & Zhao, 2024; Varsha & Prasanna, 2025).

Large-scale energy infrastructure, particularly UHV, can mitigate financing constraints through two interrelated pathways. First, a reliable electricity supply reduces production disruptions and cash-flow volatility, thereby improving firms’ creditworthiness, lowering default risk, and enhancing credit access (Fried & Lagakos, 2023; Guo et al., 2023). This improved financial stability allows firms to obtain long-term financing at lower costs and pursue riskier, innovation-intensive projects. Second, UHV projects generate positive externalities for the regional financial ecosystem by improving investment conditions and attracting financial institutions, thereby enhancing capital allocation efficiency (Fan et al., 2023; Tan et al., 2024). Collectively, these improvements strengthen firms’ financing capacity and foster a more supportive financial environment for sustained innovation. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2a UHV promotes corporate innovation by alleviating financial constraints.

With rapid technological change, digital transformation has become a critical pathway for sustaining innovation (Xu et al., 2025). However, in many developing economies, insufficient and unreliable power supply constrains digital transformation advancements, creating a pronounced “digital divide” that limits firms’ ability to adopt advanced technologies (Edeh et al., 2025). Digital transformation depends on energy-intensive technologies such as cloud computing, big data analytics, and artificial intelligence (AI), all of which require continuous and high-quality electricity to operate effectively (De Vries, 2023; Shehabi et al., 2024). When the energy supply is unstable, equipment downtime, data loss, and higher operating costs can erode firms’ innovation efficiency (Jian et al., 2023).

UHV transmission provides a structural solution by ensuring a reliable, low-volatility energy base for the digital economy. UHV stabilizes grid performance, thereby reducing outage risks and voltage fluctuations (Xie et al., 2025; Zhao et al., 2024). This ensures the continuous operation of critical digital infrastructure, such as data centers and smart manufacturing systems (Jian et al., 2023; McKinsey & Company, 2024). A stable electricity supply enables firms to operate data-driven processes more efficiently, securely, and economically, promoting the large-scale adoption of digital technologies (Poláková-Kersten et al., 2023; Sun & Min, 2024).

Building on this reliable energy base, digital transformation has become a vital channel through which UHV infrastructure promotes corporate innovation. Digitalization enhances firms’ data processing, knowledge integration, and cross-boundary collaboration abilities, thereby improving innovation efficiency and output quality (Xu et al., 2025; Yakubovich & Wu, 2025). Digital transformation expands information flows and enables data-driven decision-making to reshape organizational learning, accelerate technological renewal, and support continuous product and process innovation (Appio et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2024). Consequently, by facilitating digital transformation, UHV indirectly stimulates corporate innovation through improved information integration, resource reconfiguration, and enhanced dynamic capabilities. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2b UHV promotes corporate innovation by facilitating digital transformation.

Using panel data on Chinese listed firms from 2007 to 2023, we leverage the staggered rollout of UHV transmission projects as a quasi-natural experiment to examine their effects on corporate innovation. In China, UHV lines form the backbone of interprovincial transmission corridors, whose large transmission capacity can significantly alter the provincial electricity supply–demand balance, thereby influencing firms’ innovation activities. Accordingly, we define the treatment group at the provincial level. For each province, we identify the year in which its first backbone UHV line was commissioned, and classify firms as treated (located in provinces with UHV access from that year onward) or untreated otherwise. Lines commissioned in the second half of a calendar year (July–December) are assigned to the following year to avoid overstating contemporaneous effects. Considering the phased rollout of UHV projects across provinces between 2007 and 2023, this staggered timing provides a natural setting for a DID framework.

This identification strategy follows a well-established quasi-experimental approach that is widely used in infrastructure and policy evaluation studies (Beck et al., 2010; Olson et al., 2023). The staggered rollout of UHV projects across provinces provides temporal and cross-sectional variations. Hence, the DID framework is suitable for identifying the causal effects of large-scale infrastructure shocks. Similar designs have been applied to assess the economic and innovation effects of transportation and energy infrastructure (Andersson et al., 2023; Min & Wang, 2025; Xu et al., 2021).

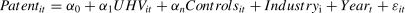

Defining treatment at the provincial level is consistent with the technological and administrative logic of UHV deployment. UHV lines are centrally planned and commissioned as interprovincial transmission corridors. Their operational effects, such as enhanced power reliability and reduced energy costs, mainly manifest through changes in provincial grid performance rather than at the individual firm level. Therefore, the timing of a province’s UHV connection provides a credible and policy-driven source of exogenous variation in firms’ operating environments. Formally, our baseline model is specified as follows:

where Patentit denotes the innovative output of firm i in year t, measured by patent applications. UHVit is a binary indicator equal to 1 if the firm’s province had UHV access in year t and 0 otherwise. Coefficient α1 captures the average treatment effect of UHV infrastructure on corporate innovation. Controlsit is a vector of firm- and province-level time-varying covariates. Industry fixed effects (Industryi) account for time-invariant sectoral characteristics, whereas year fixed effects (Yeart) absorb common macroeconomic shocks. Standard errors are clustered at the firm level to correct for potential serial correlations.Variable definitionsCorporate innovation (Patent). We measure corporate innovation using the number of patent applications filed by firm i in year t, defined as the natural logarithm of one plus the total number of patents listing the firm as an assignee (Olson et al., 2023). This indicator has been widely adopted in the innovation literature because it captures early-stage innovative activity and is less affected by administrative delays or uncertainty associated with patent grants (Nguyen & Qiu, 2022; Zhong et al., 2025). In China, patent applications, including invention, utility, and design patents, correlate strongly with R&D investment and subsequent economic performance (Dang & Motohashi, 2015), effectively reflecting the persistence of firm-level innovation (Shi & Zhu, 2024).

Key explanatory variable (UHV). Using official records from the National Energy Administration, State Grid Corporation of China, and China Southern Power Grid, we identify the commissioning year and route of each UHV line to construct province-level exposure to UHV access. Specifically, for each province, we define a binary treatment variable equal to one in and after the year when its first UHV backbone line entered operation. For direct current (DC) lines, which are typically long-distance point-to-point corridors, only the sending and receiving provinces are coded as treated. For alternating current (AC) lines, which allow multi-node integration, all provinces along the route, including intermediate nodes, are treated. This approach accounts for the spatial and technological features of UHV systems and ensures that the treatment accurately reflects firms’ potential exposure to UHV-induced benefits (Zhao et al., 2024).

Control variables. Following prior studies, we include a comprehensive set of firm- and province-level controls to mitigate omitted variable bias (Min & Wang, 2025; Ullah et al., 2022). Firm-level controls include firm age (Age), measured as the natural logarithm of years since establishment; firm size (Size), the natural logarithm of total assets; leverage ratio (Lev), total liabilities divided by total assets; cash asset ratio (Cash), cash and short-term financial assets as a share of total assets; growth capability (Growth), annual growth rate of sales revenue; audit opinion (Opinion), a dummy that equals one if the firm receives an unqualified audit opinion and zero otherwise; CEO-chair duality (Dual), a dummy that equals one if the CEO also serves as board chair and zero otherwise; equity concentration (Top1), the shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder; Big Four auditor (Big4), a dummy that equals one if audited by a Big Four accounting firm and zero otherwise; and board independence (Board), the ratio of independent directors to total board members. Province-level controls include GDP growth (GDP_growth), annual provincial GDP growth rate; population density (Pop), the natural logarithm of population divided by administrative land area; and industrial structure (Indus), the share of secondary industry value-added in GDP.

Data and descriptive statisticsThe empirical analysis uses panel data on Chinese A-share listed firms from 2007 to 2023. Data on corporate innovation and green transformation are obtained from the Chinese Research Data Services (CNRDS) platform. Data on financial and corporate governance variables are drawn from the China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) database. Province-level data are collected from the China Statistical Yearbook and related regional statistical bulletins.

The sample is constructed as follows. First, firms in the financial and insurance sectors are excluded because of the distinct nature of their balance sheets and limited comparability in innovation activities. Second, firms designated as ST or *ST for abnormal financial conditions are removed. Third, observations with missing values in key variables are dropped. Finally, all continuous variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles to mitigate the influence of outliers. The final sample comprises 40,813 firm-year observations, which is broadly consistent with prior studies on Chinese listed firms. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the main variables.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 2 presents the baseline estimates obtained using Eq. (1). Column (1) reports the results without firm- or province-level controls, Column (2) adds firm-level characteristics, and Column (3) includes the full set of controls as our preferred specification. Across all model configurations, the estimated coefficient (α1) of UHV remains positive and statistically significant at the 1 % level. These findings suggest that UHV rollout robustly promotes corporate innovation. In the preferred specification (Column 3), the estimated coefficient of 0.131 indicates that firms located in provinces connected to the UHV grid exhibit approximately 13.1 % higher innovation output, on average, than those in unconnected provinces. This magnitude is economically meaningful and comparable to the innovation-enhancing effects of major digital and transport infrastructure documented in recent studies (e.g., Andersson et al., 2023; Du & Wang, 2024). These findings provide strong empirical support for Hypothesis 1.

Baseline results.

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patent | Patent | Patent | Patent Raw | Patent Raw | |

| UHV | 0.225⁎⁎⁎ | 0.226⁎⁎⁎ | 0.131⁎⁎⁎ | 0.310⁎⁎⁎ | 0.294⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.044) | (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.049) | (0.074) | |

| Age | −0.388⁎⁎⁎ | −0.401⁎⁎⁎ | −0.388⁎⁎⁎ | −0.343⁎⁎⁎ | |

| (0.066) | (0.065) | (0.047) | (0.094) | ||

| Size | 0.329⁎⁎⁎ | 0.334⁎⁎⁎ | 0.653⁎⁎⁎ | 0.665⁎⁎⁎ | |

| (0.021) | (0.021) | (0.021) | (0.041) | ||

| Lev | −0.328⁎⁎⁎ | −0.327⁎⁎⁎ | −0.580⁎⁎⁎ | −0.531⁎⁎⁎ | |

| (0.100) | (0.099) | (0.104) | (0.164) | ||

| Cash | 0.469⁎⁎⁎ | 0.467⁎⁎⁎ | 0.368⁎⁎⁎ | 0.396⁎⁎ | |

| (0.112) | (0.113) | (0.110) | (0.192) | ||

| Growth | −0.029⁎⁎ | −0.026⁎⁎ | −0.134⁎⁎⁎ | −0.135⁎⁎⁎ | |

| (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.035) | (0.038) | ||

| Opinion | 0.356⁎⁎⁎ | 0.357⁎⁎⁎ | 0.582⁎⁎⁎ | 0.560⁎⁎⁎ | |

| (0.060) | (0.060) | (0.088) | (0.104) | ||

| Dual | 0.076⁎⁎ | 0.065* | 0.098⁎⁎⁎ | 0.097⁎⁎ | |

| (0.034) | (0.034) | (0.027) | (0.047) | ||

| Top1 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.002) | ||

| Big4 | 0.231⁎⁎ | 0.229⁎⁎ | 0.266⁎⁎⁎ | 0.264⁎⁎ | |

| (0.098) | (0.098) | (0.060) | (0.128) | ||

| Board | 0.256⁎⁎⁎ | 0.268⁎⁎⁎ | 0.226⁎⁎⁎ | 0.207 | |

| (0.090) | (0.090) | (0.080) | (0.145) | ||

| Indus | 1.517⁎⁎⁎ | 1.040⁎⁎⁎ | 1.015⁎⁎ | ||

| (0.242) | (0.223) | (0.403) | |||

| Pop | 0.106⁎⁎⁎ | 0.079⁎⁎⁎ | 0.073 | ||

| (0.020) | (0.030) | (0.048) | |||

| GDP_growth | 1.627⁎⁎ | 0.840 | 0.912 | ||

| (0.657) | (0.961) | (1.150) | |||

| Constant | 1.614⁎⁎⁎ | −5.488⁎⁎⁎ | −6.927⁎⁎⁎ | −15.541⁎⁎⁎ | −15.721⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.037) | (0.501) | (0.530) | (0.632) | (1.028) | |

| Alpha | 2.881⁎⁎⁎ | 2.394⁎⁎⁎ | |||

| (0.038) | (0.120) | ||||

| N | 40,813 | 40,813 | 40,813 | 40,813 | 40,813 |

| R2/ Chi2 | 0.303 | 0.365 | 0.370 | 13,638.66 | 4696.21 |

| Firm Controls | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province Controls | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year and Ind FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the firm level;.

We further account for the count nature of patent data to verify that the results are not driven by the distributional properties of the innovation variable. Patent applications are non-negative integers whose variance substantially exceeds the mean and exhibits a high share of zero observations, indicating over-dispersion and zero inflation. Hence, following Olson et al. (2023), we re-estimate the baseline model using negative binomial and zero-inflated negative binomial regressions, where the dependent variable is the raw number of patent applications (Patent Raw). In Table 2, Columns (4) and (5) show that the estimated coefficients of UHV remain positive and highly significant, verifying that UHV’s positive innovation effect is robust to alternative count data specifications.

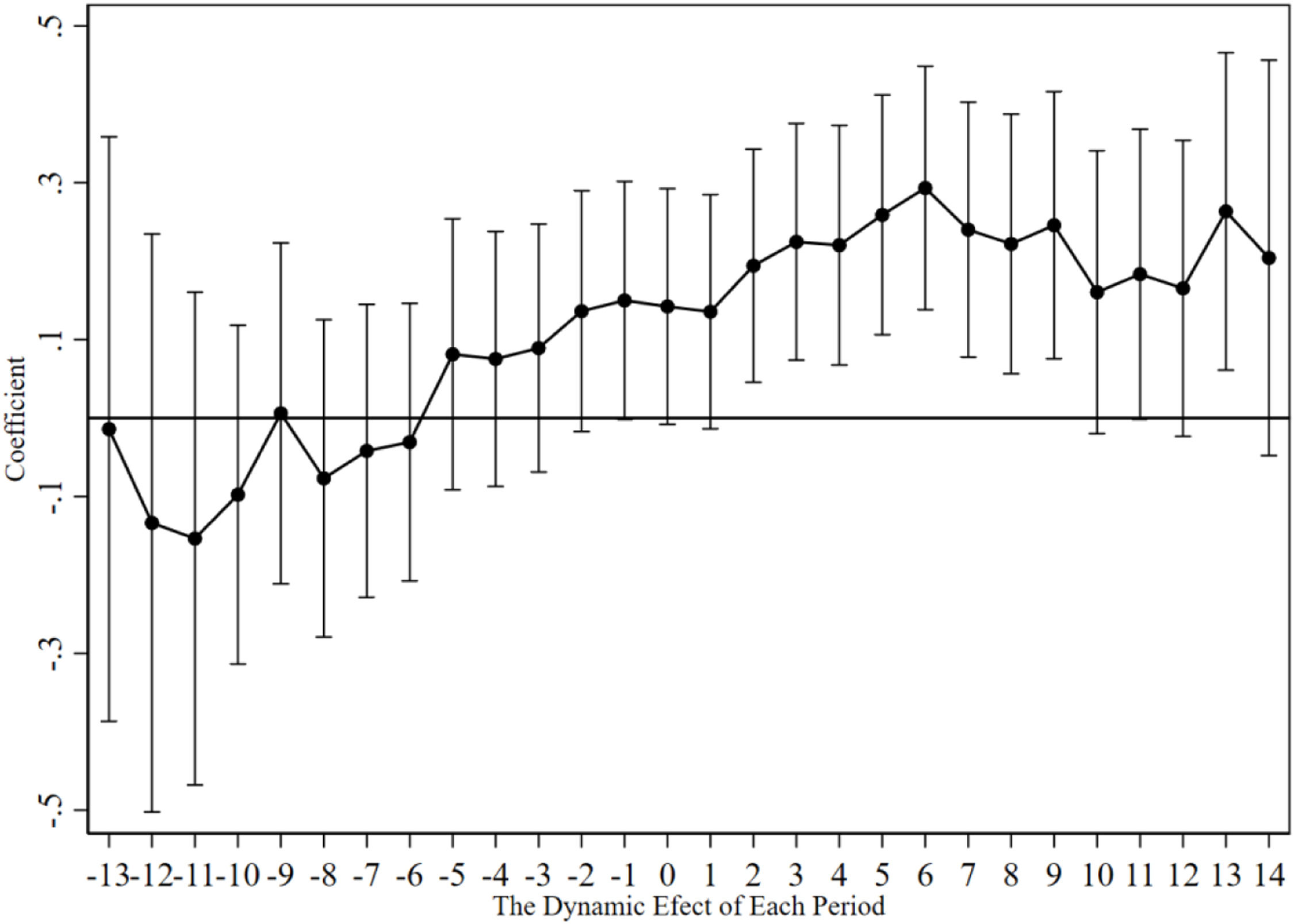

Parallel trend testThe core identifying assumption of the DID framework is that firms in treated and control provinces exhibit parallel innovation trends before the commissioning of UHV transmission lines (Rambachan & Roth, 2023). We assess the validity of this assumption and trace the temporal evolution of treatment effects using an event-study specification that estimates firms’ responses to UHV deployment relative to the commissioning year of a province’s first UHV line. This approach is well-suited to the staggered rollout setting and enables a visual inspection of pre-trend equivalence and post-treatment dynamics. Following Guo et al. (2025), we estimate the following dynamic model:

where, UHVkit represents a set of dummy variables indicating whether firm i is in a province exposed to UHV k years before or after the project’s commissioning. Specifically, k > 0 denotes years after UHV operation, k < 0 denotes years before, and k = 0 refers to the commissioning year itself. We omit UHV−14it, the earliest pre-treatment period, as the reference category. The coefficients ϑk capture the dynamic evolution of innovation differences between treated and control firms.Fig. 1 plots the estimated coefficients ϑk with 95 % confidence intervals. The coefficients before UHV commissioning are statistically indistinguishable from zero. This indicates no significant pre-trend differences between treated and control firms, thus supporting the parallel trend assumption. Starting from the second year after commissioning, the coefficients become significantly positive and continue to increase, suggesting a lagged but persistent innovation response to UHV deployment (Liu et al., 2023; Popp et al., 2019). This delayed response aligns with the adjustment period typically required for firms to recalibrate production and R&D strategies after major infrastructure upgrades. The sustained post-treatment pattern reinforces the credibility of our identification strategy, as random or spurious shocks are unlikely to generate such systematic and temporally coherent dynamics.

Placebo testFollowing Sun et al. (2025), we conduct a placebo test by randomly reassigning the UHV treatment across provinces and years to address concerns regarding non-policy confounders and potential non-random treatment assignment. Specifically, for 1000 random draws, we re‑estimate the staggered DID regression (specification (1)) using the simulated treatment indicator. Fig. 2 plots the distribution of placebo estimates. These are tightly centered around zero, whereas our true baseline estimate (Table 2, Column 3) of 0.131 lies well outside this distribution. Thus, omitted variable bias does not drive the observed UHV effect on corporate innovation.

Robustness checksAlternative dependent variableWe verify that our findings are not sensitive to innovation measures by employing several alternative dependent variables following Olson et al. (2023) and Yuan et al. (2018). Specifically, we use the number of granted patents (Patent_Grtd), as well as invention (Patent_Inv), utility model (Patent_UM), and design (Patent_Dsn) patent applications as alternative proxies for corporate innovation. These indicators capture different stages and intensities of innovative activity, from high-novelty invention patents to more incremental utility and design improvements, thereby providing a comprehensive test of robustness. Table 3 shows that the coefficient of UHV remains significantly positive across all specifications, confirming the robustness of the baseline results.

Alternative dependent variable results.

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| patent_Grtd | patent_Inv | patent_UM | patent_Dsn | |

| UHV | 0.128⁎⁎⁎ | 0.092⁎⁎⁎ | 0.081⁎⁎ | 0.060⁎⁎ |

| (0.038) | (0.035) | (0.032) | (0.025) | |

| Age | −0.363⁎⁎⁎ | −0.260⁎⁎⁎ | −0.273⁎⁎⁎ | 0.006 |

| (0.061) | (0.055) | (0.052) | (0.040) | |

| Size | 0.311⁎⁎⁎ | 0.322⁎⁎⁎ | 0.245⁎⁎⁎ | 0.142⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.020) | (0.019) | (0.017) | (0.015) | |

| Lev | −0.296⁎⁎⁎ | −0.190⁎⁎ | −0.137* | −0.042 |

| (0.093) | (0.085) | (0.077) | (0.057) | |

| Cash | 0.359⁎⁎⁎ | 0.473⁎⁎⁎ | 0.232⁎⁎⁎ | 0.646⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.104) | (0.097) | (0.088) | (0.077) | |

| Growth | −0.045⁎⁎⁎ | −0.017 | −0.029⁎⁎⁎ | −0.028⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.012) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.007) | |

| Opinion | 0.256⁎⁎⁎ | 0.291⁎⁎⁎ | 0.227⁎⁎⁎ | 0.040 |

| (0.056) | (0.050) | (0.048) | (0.031) | |

| Dual | 0.057* | 0.051* | −0.001 | 0.121⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.032) | (0.030) | (0.028) | (0.025) | |

| Top1 | 0.001 | −0.000 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Big4 | 0.197⁎⁎ | 0.223⁎⁎ | 0.123 | 0.126⁎⁎ |

| (0.093) | (0.087) | (0.081) | (0.064) | |

| Board | 0.219⁎⁎⁎ | 0.238⁎⁎⁎ | 0.165⁎⁎ | 0.064 |

| (0.084) | (0.078) | (0.072) | (0.057) | |

| Indus | 1.470⁎⁎⁎ | 0.857⁎⁎⁎ | 1.507⁎⁎⁎ | 0.592⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.224) | (0.215) | (0.191) | (0.137) | |

| Pop | 0.095⁎⁎⁎ | 0.095⁎⁎⁎ | 0.047⁎⁎⁎ | 0.007 |

| (0.019) | (0.017) | (0.016) | (0.011) | |

| GDP_growth | 0.973 | 1.402⁎⁎ | 1.117⁎⁎ | 0.081 |

| (0.607) | (0.566) | (0.521) | (0.410) | |

| Constant | −6.299⁎⁎⁎ | −7.087⁎⁎⁎ | −5.203⁎⁎⁎ | −3.449⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.498) | (0.473) | (0.429) | (0.362) | |

| N | 40,813 | 40,813 | 40,813 | 40,813 |

| R2 | 0.386 | 0.323 | 0.372 | 0.188 |

| Year and Ind FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the firm level;.

We exclude provinces affected by China’s LCCP, launched in 2010, to mitigate potential bias from overlapping policy interventions. Covering regions such as Guangdong, Shenzhen, Hangzhou, and other pilot cities, the LCCP aims to reduce emissions through energy structure optimization and efficiency improvements, which may directly shape firms’ innovation incentives. Thus, we drop observations from these regions to avoid potential confounding. Column (1) of Table 4 shows that the estimated coefficient of UHV remains positive and significant, confirming the robustness of our findings.

Excluding concurrent policies and PSM-DID results.

| LCCP | PSM-DID | |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

| Patent | Patent | |

| UHV | 0.129⁎⁎⁎ | 0.176⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.049) | (0.061) | |

| Constant | −7.043⁎⁎⁎ | −6.312⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.649) | (0.679) | |

| N | 27,799 | 11,079 |

| R2 | 0.357 | 0.385 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes |

| Year and Ind FE | Yes | Yes |

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the firm level; *p < 0.1, ⁎⁎p < 0.05,.

We employ a PSM-DID approach following Guo et al. (2025) to further address the potential selection bias arising from systematic differences in firm characteristics. Specifically, for each treated firm, we identify a nearest-neighbor match from the control group based on observable covariates, including Age, Size, Lev, Cash, Growth, Opinion, Dual, Top1, Big4, and Board. The matching procedure ensures covariate balance between treated and control firms, thereby improving comparability between the two groups. We then re-estimate specification (1) using the matched sample. As Column (2) of Table 4 shows, the estimated treatment effect remains positive and statistically significant, indicating that our baseline results are robust to the potential selection of observables.

Instrumental variable strategyWe address the potential endogeneity arising from unobserved provincial characteristics that may jointly influence UHV routing and corporate innovation using an IV approach, following Lipscomb et al. (2013). Although UHV deployment is centrally planned and largely exogenous to firm-level decisions, provincial environmental and geographic constraints may affect line placement, potentially introducing bias. We use the number of nature reserves in each province as an IV for UHV access. This instrument satisfies the relevance condition because UHV routing decisions systematically avoid ecologically sensitive zones, making the distribution of protected areas a binding constraint in project siting. It also meets the exogeneity condition because the designation of nature reserves reflects long-standing conservation policies that predate and are unrelated to firms’ innovation activities.

Table 5 reports the first- and second-stage regression results. The instrument is strongly correlated with UHV exposure, with the Kleibergen–Paap rk LM statistic rejecting the null hypothesis of under-identification at the 1 % level. The Kleibergen–Paap rk Wald F statistic exceeds the Stock and Yogo (2005) critical thresholds, mitigating concerns about weak instruments. The second-stage estimates remain positive and statistically significant, consistent with the baseline results. Collectively, the IV estimates reinforce the causal interpretation of the UHV effect and lend credibility to the identification strategy.

Instrumental variable strategy results.

| Variables | (1) | (2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UHV | Patent | |||

| IV | 0.0004⁎⁎⁎ | |||

| (0.000) | ||||

| UHV | 0.961⁎⁎ | |||

| (0.386) | ||||

| N | 40,813 | 40,813 | ||

| R2 | 0.516 | 0.062 | ||

| Controls | Yes | Yes | ||

| Year and Ind FE | Yes | Yes | ||

| Kleibergen-Paap rk Wald F | 366.195[16.38] | |||

| Kleibergen-Paap rk LM | 216.831⁎⁎⁎ | |||

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the firm level; *p < 0.1,.

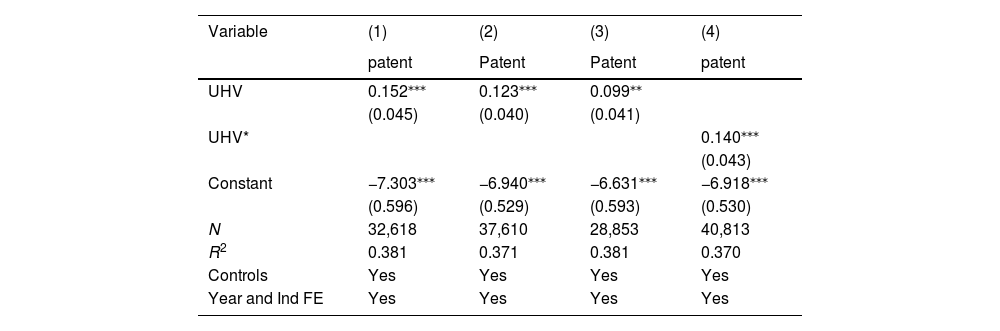

We conduct a series of complementary tests to further assess the robustness of the main findings. First, given that municipalities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Chongqing exhibit distinct administrative structures, policy intensity, and industrial composition, we exclude these cities to alleviate potential estimation bias. As Column (1) of Table 6 shows, the estimated coefficient of UHV remains significantly positive and closely aligned with the baseline results, indicating that our findings are not driven by outlier regions.

Additional robustness checks.

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| patent | Patent | Patent | patent | |

| UHV | 0.152⁎⁎⁎ | 0.123⁎⁎⁎ | 0.099⁎⁎ | |

| (0.045) | (0.040) | (0.041) | ||

| UHV* | 0.140⁎⁎⁎ | |||

| (0.043) | ||||

| Constant | −7.303⁎⁎⁎ | −6.940⁎⁎⁎ | −6.631⁎⁎⁎ | −6.918⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.596) | (0.529) | (0.593) | (0.530) | |

| N | 32,618 | 37,610 | 28,853 | 40,813 |

| R2 | 0.381 | 0.371 | 0.381 | 0.370 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year and Ind FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the firm level;.

Second, we exclude 2020 to account for potential distortions arising from the COVID-19 pandemic. Column (2) confirms that the main result holds, indicating that the conclusions are not sensitive to extreme shocks during the sample period.

Third, we restrict the sample to the pre-2021 period to mitigate any confounding influence of policy repositioning under the 14th Five-Year Plan. The results in Column (3) remain stable and significant, further ruling out contamination from recent strategic shifts in infrastructure planning.

Finally, we adopt an alternative specification for the treatment variable by defining UHV (UHV*) implementation based on annual project completion at the provincial level, disregarding the exact month of line activation. Column (4) shows that the results are robust. Altogether, these additional robustness checks reinforce the validity and generalizability of our empirical conclusions.

Heterogeneity analysesTransmission direction and regional heterogeneityConsidering the spatial mismatch between energy endowments and economic activity, UHV deployment is unlikely to have uniform innovation effects across regions. We explore two heterogeneity dimensions: the province’s role in the electricity transmission network (input versus output) and its stage of regional development (eastern versus central-western China).

Transmission direction. We first interact UHV with a dummy variable (Input) that equals one for electricity-importing provinces and zero for electricity-exporting provinces. As Column (1) of Table 7 reports, the coefficient of (UHV × Input) is significantly negative, indicating that UHV’s innovation-enhancing effect is stronger in electricity-exporting provinces. This pattern aligns with the notion that marginal returns on infrastructure investment are higher where grids are less developed and transmission bottlenecks are more binding (Foster et al., 2023). By improving outbound transmission reliability and enforcing stricter grid standards at the source, UHV reduces curtailment risks, enhances system stability, and creates stronger incentives for technological upgrading in exporting regions.

Heterogeneity analysis results.

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patent | Patent | Patent | Patent | |

| UHV | 0.270⁎⁎⁎ | 0.211⁎⁎⁎ | 0.218⁎⁎⁎ | 0.101* |

| (0.069) | (0.060) | (0.059) | (0.057) | |

| UHV × Input | −0.212⁎⁎⁎ | |||

| (0.071) | ||||

| UHV × East | −0.143⁎⁎ | |||

| (0.062) | ||||

| UHV × HighCapacity | −0.127* | |||

| (0.065) | ||||

| UHV × Manufacturing | 0.130⁎⁎ | |||

| (0.062) | ||||

| Constant | −7.017⁎⁎⁎ | −7.044⁎⁎⁎ | −7.007⁎⁎⁎ | −5.689⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.535) | (0.535) | (0.533) | (0.596) | |

| N | 40,813 | 40,813 | 40,813 | 40,813 |

| R2 | 0.371 | 0.371 | 0.370 | 0.241 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year and Ind FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the firm level;.

Regional heterogeneity. We further examine development-stage disparities by interacting UHV with a dummy variable (East) that equals 1 for eastern provinces and 0 for central-western regions. Column (2) of Table 7 shows that the coefficient of (UHV × East) is significantly negative (–0.143⁎⁎). Thus, the marginal innovation effect of UHV is 0.143 points lower in eastern provinces relative to the central-western regions. This attenuation is consistent with the already mature infrastructure and innovation ecosystems in eastern China, which limit the incremental benefits of further grid improvements. In contrast, the central-western regions, with more severe infrastructure gaps and energy supply constraints, receive disproportionate benefits because UHV alleviates bottlenecks, stabilizes production environments, and unlocks latent innovation potential (Wang et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2020).

Grid absorptive capacityWe also examine whether the impact of UHV depends on the local grid absorptive capacity. Although UHV enables large-scale interregional electricity transmission, its innovation benefits are likely moderated by a province’s ability to absorb and distribute power efficiently.

We capture this by constructing a binary indicator (HighCapacity) that equals one if a province’s substation capacity (above 35 kV) exceeds the sample median. Column (3) of Table 7 shows that the interaction term (UHV × HighCapacity) is significantly negative, indicating that UHV has stronger innovation-enhancing effects in provinces with weaker grid absorptive capacity.

Although these results may appear counterintuitive, they align with the principle of diminishing marginal returns on infrastructure investment (Donaldson, 2018). In low-capacity areas, UHV expansion relaxes binding energy constraints, reduces supply volatility, and improves production reliability, thereby creating conditions that are particularly conducive to innovation. Moreover, grid upgrades in capacity-constrained regions often coincide with complementary policy measures, such as preferential electricity pricing or targeted innovation subsidies, further amplifying UHV’s innovation benefits.

This finding reinforces our earlier heterogeneity results by transmission direction and regional location, which similarly revealed stronger effects in electricity-exporting and less-developed central-western provinces. Overall, these results highlight a consistent mechanism. Specifically, UHV delivers greater innovation payoffs in structurally constrained environments, whether owing to geographic disadvantages or limited grid capacity. This pattern is consistent with the convergence logic of neoclassical growth theory (Barro & Sala-i-Martin, 1992) and evidence that infrastructure investment yields higher marginal returns under tighter baseline constraints (Foster et al., 2023). Our results suggest that, rather than widening regional disparities (He et al., 2024; Sun & Min, 2024), large-scale energy projects such as UHV can act as equalizing forces, narrowing the gaps in development and innovation capacity across regions.

Industry structureThe impact of UHV may also differ across industries because of variations in economic composition and energy intensity. Electricity constitutes a vital production input for manufacturing firms, which are more vulnerable to power shortages and supply fluctuations (Doan et al., 2025). Power supply disruptions can directly hinder production continuity and crowd out resources that would otherwise be allocated to R&D and innovation. In contrast, non-manufacturing sectors, such as services, are generally less energy-dependent and more resilient to short-term supply volatility.

We assess this heterogeneity by classifying firms into manufacturing and non-manufacturing sectors to construct a dummy variable (Manufacturing) that equals 1 for manufacturing firms. We then interact it with UHV (UHV × Manufacturing). Column (4) of Table 7 reports a significantly positive coefficient for the interaction term, indicating that UHV’s innovation-enhancing effect is substantially stronger among manufacturing firms. This pattern underscores energy infrastructure’s sector-specific role. By alleviating power constraints, lowering production costs, and stabilizing energy supply, UHV creates an enabling environment for innovation-intensive manufacturing activities (Min & Wang, 2025).

Consistent with extant research, energy-intensive industries exhibit larger productivity and innovation gains from infrastructure investments that reduce uncertainty in energy availability (Bao et al., 2024; Cheng et al., 2021). This evidence broadly reinforces a unifying mechanism throughout our analysis. UHV yields greater innovation benefits in more constrained settings, whether geographic, institutional, or sectoral, by relaxing the key bottlenecks that suppress firms’ innovative potential (Zhao & Dong, 2025). These results highlight that energy infrastructure enhances efficiency and acts as a structural equalizer that supports high-value, innovation-driven industrial upgrading.

Further analysesMechanism testsWe examine two mechanisms through which UHV deployment promotes corporate innovation: alleviating financing constraints and facilitating digital transformation.

Financing constraintsA substantial body of literature identifies financing constraints as a key innovation barrier, particularly under high uncertainty and long investment horizons (Hall & Lerner, 2010; Liu & Zhao, 2024; Varsha & Prasanna, 2025). Electricity shortages can intensify these frictions by lowering capital productivity and increasing borrowing costs (Abeberese, 2017). However, improvements in energy infrastructure, such as UHV, can stabilize cash flows, reduce production costs, and mitigate operational risks—thereby enhancing firms’ competitiveness, creditworthiness, and ultimately easing access to external finance (Gou et al., 2024).

We empirically test this mechanism following Amore et al. (2013) and Brown et al. (2019) and use the Kaplan–Zingales (KZ) index as a proxy for firm-level financial constraints; higher values indicate tighter financing conditions. As Column (1) of Table 8 shows, UHV access is associated with a significant decrease in the KZ index, suggesting that treated firms experience a relaxation of financial constraints. Extant evidence links relaxed financing constraints to enhanced innovation performance (Fan et al., 2023). Thus, our results suggest that UHV promotes corporate innovation by alleviating financing constraints that hinder firms’ long-term R&D.

Digital transformationDigital transformation is widely recognized as a key driver of corporate innovation (Xu et al., 2025). However, effective digital technology deployment is highly dependent on reliable and affordable energy infrastructure. UHV enhances the stability and accessibility of the electricity supply, thereby improving the external environment for digital investment and facilitating firms’ technological adoption (Xie et al., 2025; Zhao et al., 2024).

We investigate whether digital transformation serves as a mechanism through which UHV promotes innovation by constructing a firm-level index of digital transformation (DT) using machine learning and textual analysis. Following Wu et al. (2022), we extract the frequency of keywords related to digital technologies, such as “artificial intelligence,” “big data,” “blockchain,” and “digital application,” from the annual reports of listed firms and take the logarithm of the total frequency as a proxy for DT. As Column (2) of Table 8 shows, firms in UHV-covered regions exhibit significantly greater digital transformation. Thus, by enhancing power reliability and reducing deployment frictions, improved energy infrastructure lowers the barriers to digitalization. UHV facilitates digital technology uptake, thereby indirectly strengthening firms’ innovation capabilities. This aligns with extant evidence linking digital transformation to innovation outcomes (Zhuo & Chen, 2023). Furthermore, it underscores a novel pathway through which large-scale infrastructure investment can stimulate innovation by directly improving operational conditions as well as by enabling complementary technological upgrades.

Regional resource reallocationBeyond firm-level mechanisms, UHV transmission may foster innovation by reshaping the regional allocation of fiscal, human, and capital resources. In many developing regions, innovation activities are constrained by coordination failures and capital-labor misallocation, potentially distorting resource allocation and weakening investment incentives (Liu, 2021; Wang et al., 2025). Energy infrastructure can serve as a corrective force by enhancing production efficiency and facilitating factor mobility across regions and sectors. Empirical evidence from China’s large-scale transportation and energy projects shows that such investments alleviate resource misallocation and stimulate productivity growth by channeling resources toward more efficient and innovation-oriented sectors (Orea et al., 2024; Zeng et al., 2025).

Following Feng et al. (2023), we construct three proxies to capture regional adjustments in fiscal, human, and capital resources after UHV deployment: (1) S&T Share, encompassing the ratio of government expenditure on science and technology to total fiscal spending and reflecting fiscal prioritization toward innovation-supportive activities; (2) EduPop, representing the number of higher-education students per 10,000 population to indicate local human–capital accumulation and talent formation; and (3) FAI Growth, reflecting the annual growth rate of fixed-asset investment to capture the pace of capital formation and infrastructure upgrading. The regression results in Table 9 show that UHV access is significantly associated with higher S&T Share, faster FAI Growth, and improved EduPop outcomes.

Resource reallocation results.

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S&T Share | EduPop | FAI Growth | |

| UHV | 0.007⁎⁎⁎ | 25.542⁎⁎⁎ | 0.013⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.000) | (1.201) | (0.001) | |

| Constant | −0.016⁎⁎⁎ | −163.629⁎⁎⁎ | 0.109⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.004) | (19.426) | (0.012) | |

| N | 40,813 | 40,813 | 40,813 |

| R2 | 0.607 | 0.463 | 0.529 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year and Ind FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the firm level; *p < 0.1, ⁎⁎p < 0.05,.

These effects likely operate through two mutually reinforcing pathways. First, enhanced energy infrastructure increases regional attractiveness, encouraging the agglomeration of skilled labor and innovative firms (Zhao et al., 2024). Second, large-scale investment induced by UHV deployment stimulates industrial upgrading and mobilizes both public and private investment in complementary assets such as smart factories, industrial parks, and digital platforms (Xu et al. 2021). These dynamics cultivate an innovation-conducive regional environment that enables firms to experiment with, scale, and commercialize new technologies more effectively.

In summary, by integrating physical connectivity with institutional incentives, UHV acts as a coordination device that facilitates a more efficient allocation of public and private resources (OECD, 2024). Consequently, UHV’s contribution to innovation extends beyond ensuring a reliable power supply. It operates through the coordinated reallocation of fiscal, human, and capital resources, thereby collectively enhancing firms’ innovation capacity and regional competitiveness (Feng et al., 2023).

Green transformationIn China’s transition toward green and low-carbon development, UHV infrastructure plays a pivotal role in enabling large-scale, long-distance clean energy transmission. UHV enhances cross-regional electricity dispatch and optimizes resource allocation, thus helping to restructure China’s energy mix and accelerate the formation of a modern, sustainable power system, which is essential for achieving economic upgrading and environmental goals (Cheba et al., 2022; Gugler et al., 2024). Corporate green transformation bridges national environmental objectives and firm-level strategic adaptation, encompassing production upgrades, cleaner energy use, and low-carbon innovation (Khanra et al., 2022; Zhai & An, 2020). However, considering the costs and uncertainties of green transition, many firms may hesitate to pursue sustainability without adequate external support (Ouyang et al., 2020). Accordingly, we examine whether UHV infrastructure facilitates corporate green transformation.

We capture firm-level green transformation using two complementary measures. First, we use the logarithms of the number of green-related patent applications (Green) and granted patents (Green_Grtd) as direct indicators of green innovation (Cheng et al., 2024). Second, we assess the textual dimension of green transformation by taking the logarithm of the frequency of green-related keywords from firms’ annual reports (GTWord) and then construct a green transformation index (GTIndex) (Loughran & McDonald, 2011).

The results in Table 10 show that UHV access significantly increases Green and Green_Grtd. Hence, UHV deployment stimulates firm-level green innovation. Moreover, UHV exposure increases GTWord and GTIndex, suggesting that firms in UHV-connected provinces are more likely to integrate sustainability themes into their strategic narratives and operational priorities. These results collectively suggest that UHV not only promotes technological upgrading but also drives ecological modernization within firms. Therefore, UHV enhances the reliability and quality of electricity, particularly from renewable sources—subsequently reducing the costs and uncertainties associated with green production. The resulting stability in energy supply encourages firms to invest in energy-efficient innovation and adopt cleaner production technologies. Through this pathway, UHV provides a stable foundation for sustainable innovation and low-carbon growth, supporting China’s transition toward a more resilient and low-carbon economy.

Green transformation results.

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green | Green_Grtd | GTWord | GTIndex | |

| UHV | 0.046* | 0.046⁎⁎ | 0.688⁎⁎ | 0.053⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.025) | (0.022) | (0.290) | (0.019) | |

| Constant | −9.236⁎⁎⁎ | −7.554⁎⁎⁎ | −24.209⁎⁎⁎ | −0.851⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.347) | (0.311) | (3.530) | (0.210) | |

| N | 40,813 | 40,813 | 40,700 | 40,700 |

| R2 | 0.419 | 0.410 | 0.332 | 0.385 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year and Ind FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the firm level;.

This study investigates the effects of the staggered rollout of UHV transmission projects on corporate innovation in China using panel data of listed firms from 2007 to 2023. Multiple model specifications and robustness checks consistently show that UHV deployment significantly enhances corporate innovation. The effects are particularly pronounced in electricity-exporting provinces, central-western regions, areas with weaker grid capacity, and manufacturing firms. These findings indicate that UHV yields greater innovation returns in structurally constrained environments. Mechanism analyses reveal two firm-level channels through which UHV promotes innovation: alleviating financing constraints and facilitating digital transformation. A reliable and stable electricity supply improves firms’ access to external finance and reduces investment uncertainty while supporting the continuous operation of data-driven technologies and digital infrastructure that underpin innovation. Beyond firm-level mechanisms, UHV fosters regional resource reallocation, reflected in higher government R&D spending, faster fixed-asset investment growth, and enhanced human–capital accumulation, signaling a more favorable regional innovation environment. Additionally, UHV advances corporate green transformation, thereby promoting green patenting and sustainability-oriented strategies.

Our findings are consistent with those of Min and Wang (2025), who show that UHV promotes green upgrading in manufacturing through collaborative innovation. However, distinct from their sectoral evidence, we employ a broader, multi-industry sample and enhance identification through extensive robustness checks to reveal micro-level mechanisms and provide new empirical insights. Furthermore, our results complement those of Jia et al. (2023), who report that electricity shortages hinder digitalization. In contrast, we demonstrate that the stable electricity supply provided by UHV enhances firms’ digital adoption and innovation investment, forming a coherent pathway from energy reliability to digital transformation, and ultimately to innovation. Contrary to concerns that large-scale energy projects may exacerbate regional inequality or induce a “resource-curse” (He et al., 2024; Sun & Min, 2024), our evidence indicates that UHV exerts stronger innovation effects in less-developed regions. This is consistent with Foster et al. (2023), who argue that infrastructure yields higher marginal returns when baseline constraints are tighter. Overall, UHV serves not only as a stable energy backbone but also as a catalyst for firm-level technological innovation and green transformation.

Theoretical implicationsThis study contributes to the innovation and infrastructure literature in three ways. First, it broadens the external and supply-side perspectives on innovation determinants. Extant research mainly emphasizes demand shocks or firm-specific characteristics (Fusillo et al., 2025; Glaeser et al., 2023; Trunschke et al., 2024), whereas infrastructure, especially energy transmission, has often been treated as exogenous. By providing firm-level causal evidence, we demonstrate that reliable energy infrastructure enhances firms’ innovation incentives. Moreover, we identify two firm-level channels for alleviating financing constraints and facilitating digital transformation, thus clarifying how energy infrastructure fosters capability development and sustained innovation.

Second, this study extends the resource-based and innovation-systems perspectives by conceptualizing energy reliability as a capability-enabling resource. By enhancing the predictability and continuity of the electricity supply, UHV provides the foundational input that supports energy-intensive digital technologies such as cloud computing, big data, and AI. These technologies reinforce firms’ dynamic capabilities in sensing, learning, and reconfiguring resources, enabling continuous technological upgrading (Nambisan et al., 2019; Poláková-Kersten et al., 2023). Hence, infrastructure operates not only as a physical asset but also as a systemic and institutional innovation enabler.

Finally, our findings refine the understanding of the conditionality of infrastructure returns. The stronger innovation effects of UHV observed in less-developed regions provide micro-level evidence for conditional convergence theory. This suggests that infrastructure investments yield higher innovation returns when structural bottlenecks are more binding. These findings challenge deterministic “resource-curse” narratives and highlight that infrastructure outcomes depend on governance capacity and policy coordination (Badeeb et al., 2017). In the Chinese context, UHV illustrates how centralized planning and regional coordination can transform energy infrastructure from a potential source of imbalance to a catalyst for inclusive and innovation-driven growth. Collectively, these insights expand the theoretical boundaries of innovation research by integrating supply-side infrastructure dynamics into firm-level innovation analysis. This provides a foundation for future research on the institutional and technological enablers of sustainable industrial transformation.

Managerial and policy implicationsOur findings provide actionable implications for managers, policymakers, and stakeholders concerned with energy infrastructure, innovation, and sustainable development. First, at the firm level, a stable and reliable electricity supply should be regarded as a strategic innovation enabler rather than a mere production input. UHV deployment creates a more predictable operating environment by reducing power disruptions and mitigating cash-flow volatility. Therefore, managers should integrate energy reliability into long-term innovation planning and enterprise risk management. Such integration strengthens the “energy–digital–innovation” nexus by aligning energy-efficiency programs, digital transformation initiatives, and R&D investment within a unified strategic framework, thus enhancing firms’ absorptive capacity, technological resilience, and competitiveness.

Second, at the regional and industrial levels, governments should align infrastructure investment with industrial upgrading and innovation policy. In electricity-importing regions, policies should promote green industrial transformation by tightening energy-efficiency standards and implementing environmentally oriented industrial access regulations. In electricity-exporting regions, complementary measures, such as local innovation platforms, ecological compensation mechanisms, and technology diffusion programs, can mitigate the risk of industrial hollowing-out and ensure that energy transmission aligns with local upgrading objectives. Such coordinated strategies can foster more balanced and synergistic regional development, ensuring that the innovation benefits of infrastructure investment are broadly shared across regions.

Third, at the institutional and policy levels, governments should establish cross-sector governance mechanisms linking energy planning, financial support, and innovation policy. Policy instruments, such as green credit programs, innovation-oriented financing, and digital infrastructure subsidies, can reduce firms’ transformation costs and amplify the innovation spillovers of infrastructure investment. Simultaneously, accelerating electricity market reform, improving grid-trading mechanisms, and strengthening intellectual property protection can enhance resource allocation efficiency and ensure that energy reliability translates into sustained technological progress.

Finally, from a developing-economy perspective, China’s UHV experience highlights a generalizable principle. Specifically, sustained innovation and industrial upgrading require a stable high-quality energy supply. For economies with stronger fiscal and technological capacity, policy priorities should focus on forward-looking spatial planning, regional coordination, and cross-border grid connectivity to enhance system efficiency and innovation potential. For countries with limited resources, phased and regionally targeted investments—supported by hybrid financing models such as public–private partnerships, crowdfunding (Mangudhla et al., 2025), and digital finance platforms (Cao, 2023)—can gradually improve energy reliability and foster localized innovation ecosystems.

China’s UHV practices offer a transferable framework for other developing economies. It demonstrates how large-scale energy infrastructure, when embedded within coherent governance and innovation systems, can transform structural constraints into drivers of inclusive and innovation-led growth. By integrating energy planning, industrial policy, and innovation incentives, countries can build resilient energy systems that simultaneously advance technological progress and sustainable development, offering a pragmatic pathway to achieving SDG 7 (“affordable and clean energy”) and SDG 9 (“industry, innovation, and infrastructure”).

Limitations and research prospectsFirst, owing to data availability, our empirical analysis focuses on listed firms in China, which may not fully capture the innovation dynamics of small and medium-sized enterprises. Extending the analysis to non-listed firms may yield a more comprehensive understanding of how UHV infrastructure shapes innovation across firm types. Second, although the staggered rollout of UHV projects provides a quasi-natural experiment, unobserved regional shocks or concurrent policy interventions may bias the estimates. Future work can use alternative identification strategies or incorporate more granular regional and temporal data to further address endogeneity concerns. Third, the long-term effects of UHV infrastructure may evolve beyond the sample period. Tracking post-construction effects over a longer horizon, particularly within newly emerging innovation clusters, can provide deeper insights into the persistence and dynamic evolution of infrastructure-induced innovation.

CRediT authorship contribution statementTing Chen: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Qiuwang Cheng: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Data curation.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.