This study investigates the adoption of generative artificial intelligence in accelerator-based startups to determine which types of startups most use the technology. Internal and external factors likely to influence high usage are examined, including creativity, proactivity, industry dynamism, and absorptive capacity. Quantitative survey data were collected from 31 Valencia-based startups participating in a leading Spanish accelerator. Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis was used to determine the influence of key attributes on generative artificial intelligence usage levels. The findings reveal four pathways influencing high usage. This work contributes to the emerging literature on startups’ usage of generative artificial intelligence, offering insights into the roles of internal abilities and external conditions.

Artificial intelligence (AI) as a key component of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (Tekic & Koroteev, 2019) is transforming the startup world (Townsend & Hunt, 2019) through shifting the paradigms and practices of entrepreneurship (Chalmers et al., 2021). Defined as “a system’s ability to interpret external data correctly, to learn from such data, and to use those learnings to achieve specific goals and tasks through flexible adaptation” (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2019, p. 17), AI is gaining popularity due to its capacity to exceed human potential across a wide array of tasks and contexts (Giuggioli & Pellegrini, 2023).

The scope and use of AI have grown with the recent democratization of AI accessibility through commercialization and generative AI (GenAI), as large language models designed to create content ranging from text and videos to audio and images in a matter of seconds (Hartmann & Henkel, 2020). For example, GenAI now affords an influential source of innovation, operational efficiency, and competitive advantage for many startups (Huang & Rust, 2018). It is an external enabler of business ideas (von Briel et al., 2018) and operationally grounds many business models seeking to scale up (Iansiti & Lakhani, 2020), facilitating more efficient internal communication and knowledge transfer (Obschonka & Audretsch, 2020) while improving interactions with, and between, external stakeholders (Kietzmann & Park, 2024).

The appeal of GenAI stems from offering a substitute and complement to human action by allowing for the automation of rules-based activities performed in relatively stable contexts, while also enabling decision-making in indeterminate environments through its advanced predictive capacity (Agrawal et al., 2019). These functions are highly pertinent for startups often characterized as resource-constrained and typically operating with underdeveloped access to the resources required to survive and grow (Stinchcombe, 1965). GenAI can help founders compensate for lacks of human, physical, and financial capital as they attempt to build and scale their ventures. For instance, startups are using GenAI for a range of time- and effort-intensive venture creation tasks from the discovery of novel ideas and their testing (Davenport & Kirby, 2015) to the development of tacit knowledge and proprietary assets that can anchor a competitive advantage (Kaul, 2013).

Despite the perceived benefits of GenAI, it is equally important to recognize that GenAI adoption amongst startups is non-linear (Ransbotham et al., 2018). Ergo, GenAI use may not always be well received or remain unchallenged. For example, the US Space Force recently banned AI tools over data aggregation concerns (Manson, 2023), major corporations such as Samsung have restricted the use of ChatGPT internally due to security worries (Ray, 2023), and others have voiced issues of potential copyright infringements (The Economist, 2024). Recently, popular media have exposed unease about alleged algorithmic biases (Murgia, 2023) and an overemphasis on “shiny products” over accuracy, safety, and human concern (Hammond, 2024).

Despite these hurdles, and with current bids to ease apprehensions, for example through the signing of an AI safety pledge (Davies, 2024) and the European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act (The European Commission, 2024), the future of GenAI in startups appears promising, even seen by many as inevitable (Huang & Rust, 2018). While GenAI presents certain risks necessitating careful management, it offers immense potential to drive profits (Singla et al., 2024) and to shape innovation process (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2019). This upside potential might mitigate the fragility of new firms (Amezcua et al., 2013), demanding further clarity on what encourages and prevents startups from using GenAI.

In this work, 31 Spanish accelerator-based startups were surveyed on the intensity of their GenAI use. Guided by an organizational learning frame that perceives organizational learning as a change in organizational knowledge as a function of experience (Argyris & Schon, 1978; Cyert & March 1992; Fiol & Lyles, 1985), our driving research question targets startup characteristics likely to prompt GenAI use: What specific characteristics influence the intensity of GenAI use in startups? Four key attributes with strong theoretical grounding in startup and organizational learning literature, including creativity, proactivity, industry dynamism, and absorptive capacity (AC), are used to answer this question through fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). While numerous factors could influence GenAI usage levels, these four attributes were chosen because they represent fundamental aspects of a startup’s learning orientation, which are likely to influence the degree of GenAI integration as a strategic resource (Roberts et al., 2012).

For instance, industry dynamism — the rate of change and unpredictability within a given industry (McKelvie et al., 2011, 2018) — can impact how startups respond to technological opportunities and threats. The ability to generate novel ideas and solutions (Hennessey & Amabile, 2010), reflective of creativity, may affect how startups use GenAI to innovate and influence how they envision the integration of technology into their business models. Proactivity as a founder’s tendency to anticipate and act on future opportunities rather than merely reacting to external events (Bateman & Crant, 1993) can be crucial for startups to identify and capitalize on emerging technological potential such as that afforded by GenAI. Finally, as the ability of a startup to recognize, assimilate, and apply new knowledge (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990), AC may be the most decisive factor in determining whether a startup can successfully adopt and utilize GenAI. Startups with higher AC are expected to adopt GenAI more successfully and to continuously learn from and adapt the technology as it evolves.

Our work makes a timely contribution to theory and practice given that startups operate in unique resource-constrained environments characterized by high levels of uncertainty (McKelvie et al., 2018). These conditions mean that successful GenAI adoption becomes not merely a technological choice, but a strategic necessity (Warner & Wäger, 2019). The ability to integrate and leverage GenAI could provide startups a competitive edge, yet the factors enabling or hindering this integration are not well understood, and worryingly, some practitioner studies have evidenced a decreasing willingness to invest in AI among business leaders (Mittal et al., 2022), while scholars have suggested that entrepreneurs must clear significant barriers to adopt it (Tran & Murphy, 2023).

Furthermore, as an environment defined by innovation, plentiful resources, and mentorship, the accelerator organizational context allowed us to study a dynamic community that seeks rapid growth. Accelerator startups are often at the cutting edge of technology adoption (Cohen et al., 2019; Colombo et al., 2018), making them relevant subjects to study whether and under what configurations of environmental, individual, and organizational conditions GenAI use is prevalent. Our investigation contributes empirically to the growing body of practical knowledge on technology use in startups (e.g., Brynjolfsson & Mcafee, 2017; Tucker et al., 2024), the need for integrated approaches to the sociotechnical as well as microlevel dimensions of AI adoption (Arroyabe et al., 2024; Tursunbayeva & Chalutz-Ben Gal, 2024), and the emerging academic literature requesting more focus on AI and entrepreneurship (Schwaeke et al., 2024).

We first provide the theoretical grounding for the work, emphasizing the need for a configurational approach to the study of GenAI use. We then detail our methods, findings, and a discussion of how these findings contribute to the literature and in practice. We conclude by acknowledging the study’s limitations and suggesting avenues for future research.

Theoretical groundingOrganizational learning as a grounding for GenAI adoptionWith its ability to autonomously generate content such as text, images, and software code, GenAI enables startups to innovate, scale, and differentiate themselves in increasingly crowded markets. GenAI is transforming industries and reshaping the startup landscape, broadening access to technologies once inaccessible (e.g., due to complexity or costliness) to smaller, resource-constrained companies (Moeuf et al., 2020). However, despite the growing interest and appeal of GenAI’s productivity-enhancing and cost-reducing capacities (Chaudhuri et al., 2022), as well as an emerging body of literature on small and medium enterprises (SMEs) (e.g., Almashawreh et al., 2024; Arroyabe et al., 2024; Wei & Pardo, 2022), a significant explanatory gap remains regarding the specific characteristics that drive startups to adopt and use it. Failure to integrate GenAI might reduce competitiveness, market share, and consequently, economic returns (Baabdullah et al., 2021), whereas deploying GenAI can provide the capabilities and impulse necessary for startups to overcome knowledge and resource gaps, which is critical to scale operations (Rajaram & Tinguely, 2024).

GenAI adoption, as with previous technological innovations such as the landline or mobile telephone, is nonuniform and arguably raises the question of organizational change management involving a behavioral intention and the ability to disrupt the status quo (Schwaeke et al., 2024). Organizational change involving the use of new technologies is referred to as a process of digital transformation (Tekic & Koroteev, 2019) and viewed as a strategic imperative for contemporary leaders (Warner & Wäger, 2019), dependent upon multiple goals and objectives including cost-cutting, the generation of new forms of value creation, the introduction of new-to-market products and services, the expansion of markets, and the optimization of business processes such as human resource management (Chalutz Ben-Gal, 2019; Cubric, 2020). This digital transformation process can itself be enabled by GenAI (Kulkov, 2021, 2023), with organizations of all shapes and sizes and across all industries investing in GenAI as an external enabler to improve knowledge management and decision-making, as well as to develop capabilities to create lucrative business solutions (Chalutz Ben-Gal, 2019; Tekic & Koroteev, 2019). However, new technology adoption through digital transformation is a complex process resting on a multifaceted set of internal and external startup factors (Kulkov, 2023), and many organizations, especially those that are smaller, struggle to integrate AI into their daily operations due to gaps in individual ability and organizational learning, alongside environmental factors.

New technology adoption as a form of innovation requires agency, including resource intensive processes of searching and selecting between possible technological innovations and subsequently integrating these technologies into existing systems or creating entirely new ones (March 1991; Schumpeter, 1934). Localized startup conditions, acting in concert or in tension (e.g., organizational capacity and founder characteristics), can facilitate or impose constraints to search and adaptation processes. Usage will therefore necessitate a creative adoption involving a combination of internal competence and external knowledge acquired from entrepreneurial learning processes (Cope, 2005; Wang & Chugh, 2014).

Original knowledge creation is perceived as a critical driver of technological change, but technology can also be shaped through imitation (Aldrich & Ruef, 2006), with many intermediary actors located in between, whereby technologies can be creatively adopted through experimentation and learning loops (Argyris & Schon, 1978; Teece et al., 1997). Our theoretical framework is therefore informed by organizational learning theory (Argyris & Schon, 1978; Cyert & March 1992; Fiol & Lyles, 1985), defined as the process through which organizations modify their mental models, processes, or knowledge, to sustain or improve their performance (Dibella et al., 1996), with technology adoption considered a form of organizational learning (Woiceshyn, 2000).

Knowledge and competence accumulation are key enablers of technological change, as the absorption and exploitation of technological knowledge can drive digital technology integration and use (Schiuma et al., 2021). Organizational learning permits organizational restructuring, for example in working practices and business models (Ashkenas, 2015), at meso levels, with technological change through GenAI usage also emphasizing individuals’ skills and personalities at the micro level (Vial, 2019), given that digital transformation requires new skill development (Colbert et al., 2016). An organizational learning lens allows us to frame the interaction of individual, organizational, and environmental factors across multiple levels (Lundberg, 1995; Örtenblad, 2004; Popova-Nowak & Cseh, 2015).

Factors influencing GenAI adoptionCubric (2020) in a tertiary review of 30 literature reviews on the topic of AI adoption in business and management identified nine categories of economic and social drivers and 11 categories of economic, technical, and social barriers to AI adoption. They found that economic drivers largely derived from AI’s ability to foster nascent innovations enabling businesses to develop previously unseen and unimagined products and services to proactively stay ahead of market trends. Socially, AI is attractive due to its ability to support business sustainability through efficient resource management and enhancement of employee wellbeing by automating repetitive tasks allowing time for more creative and strategic work (Rajaram & Tinguely, 2024). Thus, the roles of individual founder creativity and proactivity are emphasized as potentially influential conditions, alongside being alert to market developments though coping with industry dynamism in GenAI adoption and use.

CreativityDefined as the generation of novel and useful ideas (Hennessey & Amabile, 2010; West, 2002), creativity is core to entrepreneurship and argued to be a precursor toward innovation (Sarooghi et al., 2015) given its association with organizational learning (Alegre & Chiva, 2013). Creative individuals benefit from a strong capacity to generate ideas that help drive new product, service, and process innovation (Baer, 2012). To conceive ideas the market accepts, entrepreneurs often experiment, disrupt routines, and challenge existing assumptions (Rosing et al., 2011), all closely associated with explorative activities (March 1991). For example, opportunity recognition, a core aspect of the entrepreneurship process (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000), rests on an individual’s ability to deploy their creativity with divergent thinking directly effecting the generation of many and novel business ideas (Gielnik et al., 2012).

Creativity is therefore an enterprising tendency (Pennetta et al., 2024) signaling curiosity, imagination, and versatility (Bejinaru, 2018). A founder’s creative capacity significantly shapes the startup’s culture, processes, and overall innovative potential, with culture as a key social factor in facilitating AI adoption (Tursunbayeva & Chalutz-Ben Gal, 2024). In the early stages of a startup, the founder mindset and creative abilities permeate the organization (Baron & Hannan, 2002) influencing hiring decisions, problem-solving approaches, and willingness to explore novel ideas (DeSantola & Gulati, 2017). Therefore, individual creativity can define an entire organization, fostering an environment either encouraging or stifling creative thinking among employees. As the primary decision-maker, the founder’s creative tendencies directly impact strategic choices, product development, and the startup’s ability to adapt to market challenges (Baron & Hannan, 2002).

Creative startups, founded by creative individuals, may be more likely to see the potential of GenAI beyond its conventional applications, exploring unique ways to integrate the technology into their business processes (Zahra, 2024). This creativity can drive the adoption of GenAI by encouraging experimentation and the development of innovative solutions differentiating the startup from competitors. A highly creative startup can better understand complex contexts and interactions (Prüfer & Prüfer, 2020) and might use GenAI to develop new products, enhance customer engagement through personalized experiences, or optimize internal processes in novel ways. Creative startups are often at the forefront of adopting disruptive technologies, viewing them as opportunities to innovate and redefine their industries. Furthermore, one perceived benefit of AI is its capacity to “free up” the creative mind from more mundane tasks, allowing creative individuals to engage in value-adding activities by exploiting their full potential (Tursunbayeva & Chalutz-Ben Gal, 2024). Thus, creativity can be considered an individual factor shaping how startups approach the adoption and utilization of GenAI.

ProactivityProactive behaviors are those that directly alter one’s environment and individuals are thought to be differentially predisposed to behave proactively in certain contexts (Bateman & Crant, 1993). Entrepreneurs are stereotypically characterized by high levels of proactivity in their roles as trailblazers and pathfinders (Cui et al., 2016), being alert to and actively scoping their environments for potential opportunities (Kirzner, 1973; Tang et al., 2012). Proactiveness has also been identified as a key driver of opportunity exploration in early-stage startups, though its expression can vary significantly across stages and contexts (Linton, 2019). Proactive individuals who exhibit a strong orientation to learning (Kyndt & Baert, 2015) will keep pace with the latest technological trends and advancements, positioning themselves at the vanguard of digital innovation. This strategic foresight enables them to organize environmental information recognizing and interpreting how knowledge, such as that related to emergent technologies, could represent an entrepreneurial opportunity in their own context (Gaglio & Katz, 2001).

Proactivity therefore refers to the degree to which a founder anticipates and acts on future opportunities or threats rather than merely reacting to current conditions (Van Ness et al., 2020). Consequently, the founder’s proactivity can become imprinted in startup operations, influencing its overall ability to take initiative and drive change (DeSantola & Gulati, 2017). Proactive startups are likely to be early adopters of innovative technologies (Rogers, 2003) using them to drive strategic initiatives and stay ahead of competitors. These startups often view technology adoption as a means to shape their future rather than merely to respond to external pressures, as exemplified through entrepreneurial leaders such as Elon Musk. Proactive individuals are more likely to be engaged in the world around them, participating in activities with the potential for constructive change and benefiting from transformational qualities associated with a vision for what is important (Bateman & Crant, 1993). Given these characteristics, startups and the entrepreneurs who lead them, if proactive, will arguably be more likely to use GenAI more heavily.

Proactive founders might take the initiative as self-starters (Prüfer & Prüfer, 2020) to explore how new technologies can create novel business models, enhance customer experiences, or optimize operations even before these benefits become widely recognized or demanded by the market, helping to explain why certain startups are more inclined than others to use GenAI across a greater range of tasks. A proactive stance allows startups to leverage GenAI as a tool for innovation and differentiation, positioning them as leaders in their respective markets. Conversely, less proactive and more routine startups (Prüfer & Prüfer, 2020; Van Ness et al., 2020) may lag in use and apply the technology limitedly, waiting until it is proven or becomes more mainstream.

Beyond these creative and proactive drivers of GenAI use, several barriers to AI adoption were also found by Cubric (2020), reflecting a need for the dynamic capability to engage in continuous organizational learning by recognizing, assimilating, and applying new knowledge (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). Economically, the relatively high cost of implementing AI systems, including data labeling and the need for human intervention grounded in specialist expertise to enhance machine learning models, presents significant epistemic and financial hurdles (Brynjolfsson & Mcafee, 2017; Moeuf et al., 2020). The “black-box” nature of AI models raises concerns about understanding, transparency, and reproducibility, while limited model generalizability and task-specific challenges can hinder broader applicability and knowledge diffusion. Therefore, beyond creativity and proactivity, AC becomes another potentially crucial ingredient in GenAI use in startups.

Absorptive capacityAs the ability of a startup to recognize, assimilate, and apply new knowledge (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990), AC can help startups better position themselves to overcome potential obstacles to GenAI use. AC enables organizational learning, viewed as a dynamic capability. In the context of GenAI, this prior knowledge is intrinsically tied to the startup’s technological base, encompassing both its existing technological infrastructure and the technical expertise of its human capital. As argued by Zahra and George (2002), AC involves not just the acquisition of external knowledge, but also its assimilation, transformation, and exploitation – processes deeply intertwined with a firm’s technological capabilities (Roberts et al., 2012). For startups considering GenAI use, their AC directly reflects their ability to understand, integrate, and leverage this perceived complex technology (Bohr & Memarzadeh, 2020), with the adoption of digital technologies facilitating the acquisition of digital capabilities (Warner & Wäger, 2019).

AI has transformed the nature and understanding of human–technology interactions (Cohen & Gal, 2024; Glikson & Woolley, 2020). For emerging technologies, a startup’s AC effectively shapes the perceived characteristics of the technology, influencing factors such as its compatibility, complexity, and relative advantage (Roberts et al., 2012). This interplay between AC and technological characteristics is particularly salient for startups, where limited resources may necessitate a tight coupling between their technological knowledge base and their adoption decisions. Nambisan et al. (2019) propose that in the digital age, technology should be viewed not just as a discrete entity, but as a socio-technical assemblage including the knowledge and capabilities required to leverage it effectively (DeLanda, 2006).

This perspective is particularly relevant for GenAI, where its potential is largely realized through integration with existing systems and application to specific business problems – processes dependent on the startup’s AC. For startups, whose technological identity often remains in flux, their AC in relation to GenAI becomes a key determinant of their technological trajectory. Startups with high AC are arguably better positioned to interpret and integrate the functionalities of GenAI, thus maximizing its potential to meet the startup’s strategic goals. This technological aptitude can facilitate the decision to adopt GenAI and may also determine the depth and success of its implementation.

For example, strong AC can strengthen, complement, or refocus a startup’s knowledge base (Zahra & George, 2002), allowing quicker incorporation of GenAI across a wider range of tasks, leveraging it to drive innovation. Furthermore, barriers such as the economic costs of GenAI adoption can be reduced by applying best practices learned through external partnerships and applying innovative approaches such as automated data labeling and active learning techniques, reducing the need for manual intervention. The limited generalizability of AI models, which restricts their applicability to specific tasks, can be addressed by continuously absorbing knowledge from both internal applications and external innovations. However, this external search for knowledge will itself be complex, given the dynamic industry settings in which startups operate.

Industry dynamismEntrepreneurs are increasingly confronted with highly volatile and everchanging environments, rapidly evolving technologies, and delicately poised political landscapes. Industry dynamism refers to the perceived rate and unpredictability of changes in the external environment in which a startup operates (McKelvie et al., 2011). Industry dynamism can directly influence how startups view the need for and potential benefits of adopting GenAI. For example, in environments perceived as highly dynamic, startups face constant shifts in market conditions, customer preferences, and technological advancements (Hakeem, 2023). These fluctuations can create both opportunities and threats, compelling startups to adopt agile and innovative technologies to remain competitive and survive (Mokhtarzadeh et al., 2022).

The ability to quickly adapt and leverage new technologies can be crucial for survival and success in rapidly changing markets (Miller & Friesen, 1983). Industry dynamism, as an external pressure, can therefore (de)incentivize technology use. Through examining industry dynamism we can better understand how startups respond to external uncertainties and how these responses drive GenAI usage levels. For example, in industries where technological advancements occur rapidly, startups may use GenAI to stay competitive or capitalize on emerging trends (Rajaram & Tinguely, 2024). Conversely, in more stable environments, the pressure to use such advanced technologies might be lower, as the external conditions do not demand rapid or radical change (Verreynne et al., 2016).

Complexity of GenAI adoptionWhile numerous social, organizational, and technical factors influencing AI adoption have been examined individually, their interconnected impact on a specific focus of GenAI remains underexplored, limiting understanding of how these dimensions collectively shape implementation outcomes for startups (Arroyabe et al., 2024). Given that our primary inquiry targets the specific characteristics influencing startups’ GenAI use, configurational theory (Iannacci & Kraus, 2023) incorporating interrelations between individual, organizational, and environmental factors emerges as the most appropriate lens to study the decision to use GenAI.

Startup processes involve dynamic and interrelated causative factors with too many variables to enable precise prediction. Startup emergence and the decision to embrace technological change to drive this process is therefore plagued by complexity. We have yet to understand how configurations involving the complex interplay of AC, startup founder characteristics that are reflective of the emergent organization, and industry dynamism can produce new, alternate forms of successful GenAI usage pathways through innovative combinations. These emergent usage patterns will possess unique qualities, as they differ from what the individual capabilities might suggest, and their combined effect on GenAI adoption success can be greater than the sum of the individual factors.

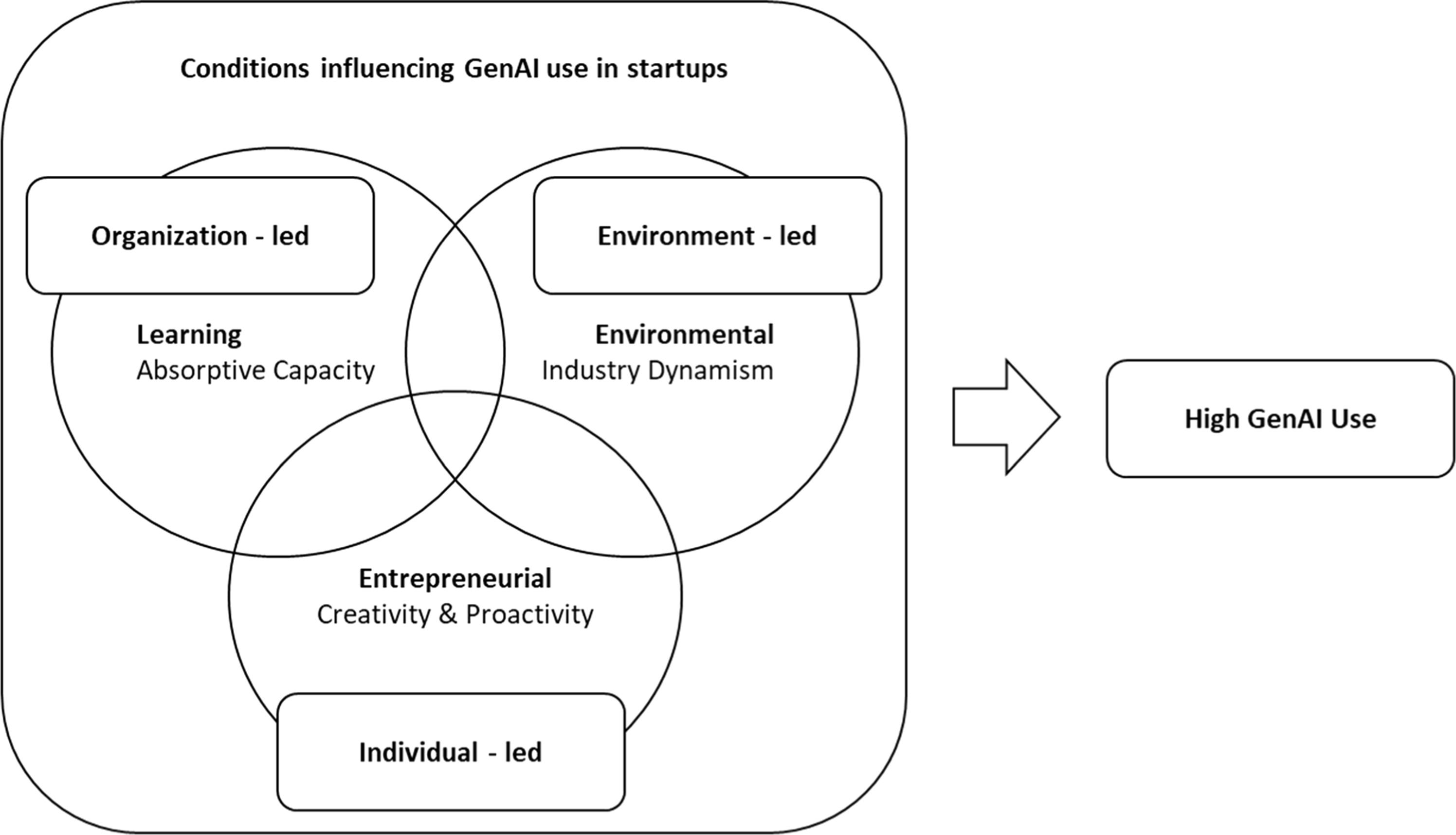

The interactions between organizational-led (AC), entrepreneurial-led (creativity and proactivity), and environmental-led (industry dynamism) conditions can create unexpected and novel pathways to high GenAI usage (Fig. 1). These configurations might represent equilibrium states that are not immediately apparent from examining the individual factors in isolation. For instance, certain combinations of these conditions might create synergistic effects that enable successful adoption in ways that cannot be predicted by simply adding up the individual effects of each condition.

GenAI adoption demonstrates intricate patterns apparently transcending traditional linear analytical approaches, as adoption occurs through multiple pathways (equifinality) where conditions act interdependently (conjunction) with attributes perhaps causally related in one configuration yet unrelated or even inversely related in another. Below we demonstrate this complexity by examining certain relational configurations that are possible.

Possible relational configurationsWhile high AC might provide the organizational foundation for GenAI use, its effectiveness may be limited without the founder’s creative vision for novel applications. AC, although important, may require creative direction to identify and capitalize on novel applications that can create value. The learning capabilities embedded within AC enable the startup to comprehend, assimilate, and implement GenAI technologies, but the transformation of these capabilities into meaningful applications may require the creative vision that typically emanates from the founder. Conversely, founder creativity, while potentially generating innovative ideas for GenAI applications, may face significant implementation barriers without sufficient startup AC.

The interaction between AC and founder proactivity may also affect patterns of GenAI use. High AC might enhance proactive GenAI adoption initiatives by providing the previously discussed organizational foundation necessary to evaluate and implement GenAI systems. However, this relationship could create adoption risks where high proactivity without sufficient AC might lead to premature GenAI implementation or the selection of inappropriate GenAI solutions. Conversely, high AC without proactive pursuit of GenAI opportunities might result in delayed use or missed competitive advantages, as organizational capabilities remain underutilized.

Industry dynamism introduces further complexity. High industry dynamism might necessitate both strong AC to evaluate fast-evolving GenAI technologies and high proactivity to implement these solutions quickly. However, this same environmental pressure could lead to hasty GenAI adoption decisions if high proactivity is not well balanced with sufficient AC for proper evaluation of GenAI capabilities and startup fit. Furthermore, creative vision could be enhanced by proactive behavior, as proactive founders actively seek novel GenAI applications and implementation opportunities. However, this relationship might create tensions, where high proactivity might urge GenAI adoption before creative use cases are fully developed or where high creativity without sufficient proactivity leads to innovative GenAI ideas remaining unimplemented.

The three-way interaction between AC, founder characteristics (creativity and proactivity), and industry dynamism clearly heightens relationship complexity. In dynamic environments, all three internal capabilities might need to work in concert, with AC providing the learning foundation to understand GenAI, creativity in identifying novel GenAI applications, and proactivity driving early use. However, in less dynamic environments, different combinations of these capabilities might prove sufficient. For instance, where competitive pressures and technological change occur at a slower pace, startups may have more flexibility in how they configure their capabilities. When industry dynamism is low, startups might successfully use GenAI through configurations emphasizing strong AC and creativity, even with lower levels of proactivity, where reduced pressure for rapid adoption may permit startups to take a more measured approach focusing on developing sophisticated technical implementations and innovative applications without the urgency that high dynamism demands. Alternatively, configurations combining high creativity and proactivity might prove sufficient in stable environments even with moderate AC. The slower pace of change allows startups to develop technical capabilities incrementally while still pursuing innovative GenAI applications.

These select relationships we have outlined demonstrate possible asymmetric effects in GenAI usage levels, where the presence or absence of conditions could have different implications depending on their configurational setup. This nuanced interpretation signals that the current understanding of configurations promoting high GenAI usage remains incomplete in several important ways (see Arroyabe et al., 2024). First, we lack comprehensive knowledge of how supportive conditions combine to elevate GenAI use in startups. While individual factors such as AC, founder characteristics, and industry dynamism have plausible importance, their combined effect in enabling high usage remains poorly understood. Second, although existing research implies that certain conditions, particularly AC, may be a sine qua non condition for high usage of GenAI, this assertion is not based on systematic cross-case comparative research that could definitively establish the necessity of conditions. Third, while existing literature suggests that AC, founder creativity and proactivity, and industry dynamism can all potentially support high usage, we lack research examining whether startups use GenAI when some of these conditions are absent or weak. This gap in understanding is particularly significant, given the resource constraints and capability limitations often faced by startups, whose idiosyncratic journeys will benefit from varied strategic options.

The diversity of available pathways requires innovation in methodological approach. The complexity makes fsQCA particularly appropriate for several reasons emphasized by Kraus et al. (2018). First, it can identify multiple paths to high GenAI use, acknowledging different possible combinations of conditions. Second, it accommodates asymmetric causality, recognizing that the presence and absence of conditions might affect usage differently. Third, it distinguishes between necessary and sufficient conditions, clarifying which factors are universally crucial versus contextually important. Fourth, it accounts for equifinality acknowledging multiple viable paths to high usage. Finally, it can identify complex combinations of conditions that might be overlooked by traditional regression methods.

We begin our analysis of GenAI use in startups guided by the previously discussed theories and literature (Di Paola et al., 2025), with the following baseline proposition:

Proposition 1. (P1): Absorptive capacity, creativity, proactivity, and industry dynamism positively affect GenAI adoption in startups.

Framed using Boolean algebra this theoretical proposition reads as follows:

Proposition 1. (P1): fsAC * fsCR* fsPRO * fsID → fsAI, where * stands for logical AND; → stands for the logical implication sign (“is sufficient for”); fs =fuzzy set; AC = absorptive capacity; CR = creativity; PRO = proactivity; ID = industry dynamism; and AI = generative artificial intelligence adoption.

MethodThe sample comprised 31 startups operating across a range of sectors including mobility, food, education, health, sport, finance, legal tech, entertainment, and logistics (see Table 1). Startups were participants in Lanzadera, a Valencia-based startup accelerator ranked seventh in the Financial Times’ 2025 list of Europe’s Leading Startup Hubs. Lanzadera is one of three components forming part of a privately governed entrepreneurial ecosystem named Marina de Empresas that holds the collective mission to educate, train, and support entrepreneurial leaders (Donaldson et al., 2024). Valencia has emerged as a leading digital entrepreneurship hub in Spain, with strong institutional support, a growing tech ecosystem, and increasing exposure to emerging technologies such as GenAI, making it an appropriate context for our study. We selected Lanzadera as our sample due to its size, national reputation, and structured program model, which offers a comparably standardized environment for early-stage startups. This homogeneity helps reduce variability in contextual factors unrelated to GenAI use, allowing for more meaningful case comparison. Furthermore, Lanzadera has been the subject of nascent scholarship on entrepreneurial ecosystems and entrepreneurial intermediaries that have shown dispersion in GenAI use and subsequent innovative performance among startups (Donaldson et al., 2025). We draw from the same sample as Donaldson et al. (2025) to investigate the factors initially raising GenAI adoption.

Description of Startups.

Sample size is of lesser concern, as we aimed to analyze the causal complexity, causal asymmetries, and equifinal pathways leading to higher usage of GenAI. Our sample size, therefore, is appropriate for our research goals, given that we seek case-comparison and not statistical representativeness (Yoruk & Jones, 2023). FsQCA is designed for small-N and medium samples, as the method analyzes configurational logic and case comparison rather than statistical generalizability (Fiss, 2011). FsQCA is thus well suited for our research setting, where the aim is to identify multiple causal pathways from a limited number of well-bounded cases.

Founders were invited to complete a confidential and anonymous online survey via their project directors, through whom the research objectives were explained. Startups entering the accelerator in September 2023 were contacted, and of the 100 startups, 31 returned completed questionnaires. The final sample was composed of 24 male and 7 female founders (average age of 33 ± 12 years), predominantly educated at the postgraduate level (58 %). Average start-up size was 5 ± 4 workers, with most startups operating at a revenue-generating stage (52 %) or at an early stage with a prototype (42 %). Fifteen startups were currently raising capital.

To determine GenAI use, founders were asked whether they have used GenAI to complete 20 different startup-related tasks through responding to a 7-point Likert scale. Example tasks included “generating an idea,” “segmenting your market,” and “maintaining relationships with partners.” Our industry dynamism measure was adapted from Jansen et al. (2005) and asked participants to indicate their level of agreement with four statements about their startup’s operating environment on a 5-point Likert scale. Example statements included, “The technology in our industry is changing rapidly” and “New customers tend to have product-related needs that are different from those of our existing customers.” We define AC as a startup’s ability to acquire, assimilate, and apply external knowledge through the sequential processes of exploratory, transformative, and exploitative learning (Lane et al., 2006). To measure AC, an aggregate measure based on these three core constructs was employed requiring respondents to state their level of agreement on a 6-point Likert scale (see Ferreras-Méndez et al., 2015).

Proactivity was measured using three items from Bateman and Crant’s (1993) proactivity personality scale. Participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale. Questions included, “If I see something that I don’t like, I fix it,” “I am always looking for better ways to do things,” and “If I believe in an idea, no obstacle can prevent me from making it a reality.” Finally, creativity was measured on a 5-point Likert scale, measuring agreement with three items adapted from Santos et al. (2019) and Santos et al. (2013), including “People are often surprised by my novel ideas,” “People often ask me for help in creative activities,” and “I prefer to do routine work rather than creative work.”

Data analysisTo examine GenAI use, we applied fsQCA, given its usefulness in understanding of how different explanatory factors combine to produce specific outcomes. Notably, fsQCA is becoming a prominent method in entrepreneurship research, as it allows investigation into configurations of factors characterized by high degrees of causal complexity (Fiss, 2007; Kask & Linton, 2013; Nikou et al., 2024). The method is based on John Stuart Mill’s “method of difference” and “method of agreement” that analyzes patterns to understand cause and effect. By applying fsQCA, we could identify those configurations of attributes most relevant for GenAI use. Boolean algebra and algorithms are used to simplify complex causal conditions and to determine specific combinations of factors consistently associated with outcomes. FsQCA helps in highlighting the critical conditions and their interactions, providing a clear understanding of the pathways to GenAI use.

FsQCA is well-suited for cross-comparing cases, especially in studies with small to medium-sized samples and was originally developed by Ragin (1987)) for small-N cross-comparative studies in political science. This, fsQCA is a highly relevant method in contexts where traditional statistical methods may struggle due to limited sample sizes (Ragin & Fiss, 2008; Rihoux & Ragin, 2009). FsQCA excels at providing a logical and systematic analysis of causal complexity without requiring large sample sizes, which makes it ideal for our study of 31 startups. By allowing for the exploration of multiple pathways to an outcome, fsQCA ensures that conditions do not compete to explain the outcome, but rather work together to provide a comprehensive understanding (Greckhamer et al., 2018). In this study, we follow the general guidelines provided for QCA analysis (Pappas & Woodside, 2021) and for entrepreneurship research (Di Paola et al., 2025; Kraus et al., 2018).

Calibration and resultsFuzzy-set calibration is the first step in fsQCA through which the outcome of interest (GenAI use) and explanatory factors referred to as “antecedent conditions” (creativity, proactivity, industry dynamism and AC) are categorized into member sets based on three qualitative anchors (Fiss, 2011). Calibration converts raw data into fuzzy sets through assigning values between 0 and 1 that reflect how strongly each case belongs to a condition (e.g., high creativity; Ragin, 2009). A value of 1 indicates full membership, 0 indicates full non-membership, and 0.5 represents maximum ambiguity, known as the intermediate set. We used the direct method for data calibration where researchers select three specific breakpoints: fully in, intermediate, and fully out. This is the preferred approach, as it affords clarity on threshold selection, resulting in more rigorous and replicable studies (Rihoux & Ragin, 2009). We selected values of 0.95, 0.50, and 0.05 as thresholds, since these provided the best-balance between coverage, solution consistency, and the solutions and are in the range of recent recommendations (Nikou et al., 2024). These thresholds are particularly effective in small to medium-sized samples, ensuring precise differentiation between full membership, intermediate membership, and non-membership. Following calibration, we constructed a truth table (Table 2) to analyze which combinations of conditions were associated with high GenAI use.

Truth Table.

Following the guidelines for smaller samples sizes (Kraus et al., 2018), we set the frequency threshold to 1, so as not to lose too much data in the small sample. We tried different levels of consistency, with the solution coverage and consistency showing the best results with a minimum consistency for a configuration at 0.73, slightly below the recommended 0.75 (Nikou et al., 2024). Still, we opted for this minimum, as the resulting configurations had higher overall coverage and consistency (0.73). We then performed a necessity analysis to identify whether any single factor must be present (or absent) for the outcome to occur in all cases. In Table 3, the results of our necessity analysis show that none of the conditions were found to be above the recommended threshold of 0.9 (Nikou et al., 2024).

Necessary Condition Table.

Following the construction of the truth table, we applied the fsQCA minimization procedure to derive simplified causal configurations. Solution coverage refers to how much of the outcome is explained by the configuration; consistency refers to how reliably a configuration leads to the outcome. The fsQCA results reveal four distinct pathways, each representing a unique configuration of conditions heightening GenAI use (see Table 4 for the full set of configurations). These pathways demonstrate the complex and often counterintuitive relationships between creativity, proactivity, industry dynamism, and AC in driving high GenAI use. A consistent finding across all pathways is the presence of industry dynamism. However, the interplay of internal organizational factors varies significantly across pathways, challenging traditional linear models of technology adoption and use. The findings demonstrate the principle of equifinality by showing that multiple pathways can raise GenAI use, while revealing the potential for compensatory and substitutive relationships between conditions, where the strength of one factor can offset the absence or irrelevance of others.

Solutions of High GenAI Adoption.

Note: Large filled circles indicate strong presence (core condition), while small filled circles indicate weaker presence (contributing condition). Large hollow circles indicate strong absence (core absence), and small hollow circles indicate weaker absence (contributing absence). Blank cells indicate that the condition does not matter in the particular configuration (i.e., can be present or absent).

Each solution can be directly linked to specific rows in the truth table (Table 2), helping to anchor the abstract configurations in the underlying data. Solution 1 (EnvDyn * ∼AbCap * ∼Proact) corresponds to the first row of the truth table, which includes three cases characterized by high industry dynamism but weak internal capacities. Solution 2 (EnvDyn * AbCap * Proact) reflects the third row, which contains five cases and shows a strong alignment of capabilities with environmental pressures. Solution 3 draws primarily on the first and fifth rows, where low creativity and low proactivity combine with dynamism to yield high GenAI use. Finally, Solution 4 reflects the third and fifth rows, highlighting firms that combine strong AC and creativity in dynamic industries. These connections show that the four solutions are grounded in the empirical distribution of cases across the truth table, reinforcing the robustness of the configurational results.

The pathways challenge accepted knowledge about the necessity of certain individual characteristics (e.g., proactivity or creativity) for high technology use and suggest that their importance may depend on context. Furthermore, the findings illustrate the complex role of AC present in some pathways, yet absent and irrelevant in others. The results point to varying usage dynamics across pathways, from forced use and reactive adoption (pathways 1 and 3) to more balanced approaches combining external pressures with internal capabilities (pathways 2 and 4) (Fig. 2).

DiscussionPathways explainedPathway 1: ∼ fsAC * ∼ fsPRO * fsID → fsAIPathway 1 shows high use of GenAI in startups occurring in the presence of industry dynamism, but surprisingly, in the absence of AC and proactivity, with creativity playing an irrelevant role. These startups are likely to exploit existing prebuilt GenAI solutions and may struggle to customize and deeply integrate GenAI into their processes, due to their low AC (Haefner et al., 2021). Their approach to GenAI adoption can be described as largely reactive and focused on basic implementation. Industry dynamism is a core condition to GenAI adoption, likely a consequence of the constant pressure exerted on these startups to innovate and adapt to survive and compete, perhaps overriding the need for internal capabilities to fully understand GenAI. For example, startups might use GenAI due to institutional pressures and the need for legitimacy, rather than based on their internal capacity. High rates of use can result even when startups lack the internal capabilities to fully leverage GenAI.

The irrelevance of creativity is noteworthy. While creativity is often associated with innovation and technology adoption (Amabile, 1988), its irrelevance here suggests that in industries perceived as highly dynamic, the external pressure to use GenAI may supersede the need for internal creative processes. In this instance, exogenous factors such as competitive pressures can compel firms to use new technologies (Majumdar & Venkataraman, 1993), largely through imitation, regardless of their internal creative capabilities. The absence of proactivity further reinforces external factor dominance over internal organizational characteristics, suggesting that even reactive startups may be obliged to use GenAI to keep pace with rapidly evolving industry standards and competitor actions.

While Pathway 1 leads to high GenAI use, it may not necessarily result in effective use or value creation given an apparent lack of internal capabilities to effectively utilize the adopted technology. It appears that GenAI is compensating for these resource deficits. For example, AI systems can allow startups to detect emergent technologies by performing a patent analysis that permits technological forecasting (An & Ahn, 2016), also allowing entrepreneurs to exceed their existing expertise and information processing capacities to craft more inventive approaches and identify increasingly imaginative opportunities (Amabile, 2019; von Krogh et al., 2023).

Pathway 2: fsAC * fsPRO * fsID → fsAIPathway 2 shows the presence of industry dynamism, AC, and proactivity, with creativity remaining irrelevant leading to high GenAI use. As with Pathway 1, industry dynamism remains crucial, but on this occasion it is complemented by strong internal capabilities, namely AC and proactivity. Pathway 2 combines strong learning capabilities with proactivity, helping to expand technological possibilities (Haefner et al., 2021). High AC can help startups to effectively learn from and integrate GenAI solutions. High proactivity means that they actively seek out new applications and use cases rather than waiting for proven solutions. These startups are likely to more effectively process and utilize new information about GenAI developments, quickly understanding and implementing new capabilities as they emerge. According to Zahra and George (2002), AC can be divided into potential AC (acquisition and assimilation of knowledge) and realized AC (transformation and exploitation of knowledge). High AC suggests that startups can not only recognize the value of GenAI (potential AC), but also to apply it effectively in their operations (realized AC). This connection between AC and application reflects the two preconditions for organizational learning: (1) the acquisition and processing of information and (2) action, in this case the high usage of GenAI (Woiceshyn, 2000).

The complementary relationship between industry dynamism and AC supports the findings of Jansen et al. (2005), who argue that in dynamic environments firms with higher AC are better positioned to reconfigure their resource base and adapt to environmental change (Warner & Wäger, 2019). Hence, for GenAI use, startups with high AC are likely to more adeptly understand, integrate, and leverage GenAI in response to constantly changing industry conditions.

High levels of proactivity further enhance a startup’s ability to capitalize on industry dynamism and their AC. Digital technologies are often seen in businesses pursuing proactive strategies, for example in supply chain management (Ben-Daya et al., 2019), the medical industry for preemptive treatments (Giorgini et al., 2023), and in other industries, as with use of the Industrial Internet of Things for real-time monitoring of machines and control systems for proactive decision making (Sisinni et al., 2018). Startups are advised to anticipate and embrace digitization in their business models and to adopt strategies allowing them to generate and evolve their dynamic capabilities (Tripsas & Gavetti, 2000). As an opportunity-seeking, forward-looking perspective characterized by the introduction of new products and services ahead of the competition, proactive startups are likely to be early adopters, seeking to gain first-mover advantages in their respective markets. Proactive startups can preempt employee apprehension to GenAI adoption and devise strategies to increase technology acceptance, for example by investing in the reskilling and upskilling of teams (Tursunbayeva & Chalutz-Ben Gal, 2024).

Creativity remains irrelevant in this pathway, suggesting a potential substitution effect between creativity and the combination of AC and proactivity. This could indicate that the ability to recognize, assimilate, and act upon external knowledge (AC) and the tendency to take initiative (proactivity) may be more influential than are internal creative processes. This substitution effect challenges traditional views on innovation, emphasizing the role of creativity (Amabile, 1988). However, it aligns with more recent perspectives on open innovation (Chesbrough, 2003), suggesting that firms can and should use external ideas and paths to market. Startups following this pathway may be relying more on external innovations (the GenAI technologies themselves) as enablers. For example, Outlier.ai is a platform that connecting subject matter experts to assist in the development of advanced GenAI models. The irrelevance of creativity raises questions about the long-term innovative potential of these startups: While they may be quick to use GenAI, their ability to creatively apply and extend these technologies may be limited.

Pathway 3: ∼ fsCR* ∼ fsPRO * fsID → fsAISimilar to Pathway 1, in emphasizing the exploitation of GenAI (Haefner et al., 2021) Pathway 3 shows high use of GenAI occurring solely in the presence of industry dynamism, with AC irrelevant and both creativity and proactivity absent. This pathway reflects startups that use GenAI heavily through necessity and standardization. Despite operating in a highly dynamic environment, their low creativity and proactivity mean that they are likely to focus on established use cases and proven applications within preset parameters. These startups may focus on process optimization, implementing GenAI in ways that are well-documented and proven, focusing on operational efficiency rather than creative applications.

Pathway 3 highlights the potential dominance of environmental factors over organizational characteristics in GenAI use. Rapidly changing industry dynamics can constrain creativity and create pressure for short-term adoption, overriding the need for internal capabilities or proactive strategies. Given environmental volatility, startups may feel compelled to use GenAI not because of their internal readiness or strategic choice, but due to external pressures to conform to emerging industry standards or to keep pace with competitors. This pathway aligns with a “reactive adaptation” strategy (Miles et al., 1978) and a population ecology that emphasizes environmental selection processes over internal adaptive capabilities (Hannan & Freeman, 2009). Startups using GenAI in this scenario are reacting to environmental pressures rather than proactively seeking opportunities or creatively exploring new applications of the technology.

While Pathway 3 may raise usage rates, the absence of AC, creativity, and proactivity generates concerns about the depth of integration and the potential for value creation from GenAI technologies. For instance, startups may display high usage rates, but might also struggle to effectively leverage the technology for competitive advantage. Potential risks can emerge especially those derivative from ‘bandwagon’ effects in technology adoption (Abrahamson & Rosenkopf, 1993) leading to suboptimal outcomes or the wasting of already scarce resources. Nevertheless, GenAI can substitute creative and proactive deficits (Rajaram & Tinguely, 2024), compensating for resource shortfalls. For example, the use of GenAI for creative purposes is distinct from established areas where AI has served as a replacement for traditional practice (Haefner et al., 2021). GenAI in startups can be used to identify and prioritize consumer preferences supporting product, process, or business model innovation (Mariani & Nambisan, 2021).

Pathway 4: fsAC * fsCR* fsID → fsAIPathway 4 shows high use of GenAI in the presence of industry dynamism, AC, and creativity, while proactivity is irrelevant. This pathway represents a sophisticated approach to GenAI use, emphasizing the interplay between external environmental factors and internal organizational capabilities. These startups combine strong learning capabilities with creative applications in highly dynamic environments, being able both to explore new possibilities and to exploit existing knowledge (Haefner et al., 2021). Their high AC allows them to quickly understand and integrate new GenAI capabilities, while their high creativity enables them to develop novel applications and use cases. These startups can effectively redefine both problem and solution spaces.

The continued presence of industry dynamism reinforces its fundamental role in influencing GenAI use across startups. Pathway 4 emphasizes the importance of adapting, integrating, and reconfiguring internal and external organizational skills, resources, and competencies to match the requirements of a changing environment. The presence of AC, as with Pathway 2, complements the effect of industry dynamism, with those firms high in AC being better able to adapt to environmental turbulence and assimilate new technologies (Van den Bosch et al., 1999). As such, startups are likely to be more adept at understanding the technology’s complexities and subsequently able to integrate the technology into their existing processes.

Creativity adds an interesting dimension to GenAI use, as creativity is frequently championed as a necessary condition for innovative activity, helping with continuous change in tactics and goals (Leiblein, 2007). Importantly, creativity alone is insufficient for innovative action (Baron & Tang, 2011), according to our current findings. For example, although a high quantity of ideas may be generated, this ideation does not automatically convert to feasible processes, commercially viable products, or services (e.g., McMullen & Shepherd, 2006).

Furthermore, it has been empirically proven elsewhere (Baron & Tang, 2011) that the need for creativity is higher in dynamic environments than those that are stable, given the need for timely innovations. For example, creativity could manifest in novel applications of the technology, innovative business models leveraging GenAI, creative solutions to implementation challenges, or encouragement of an experimentation culture in which team members feel empowered to explore the uses of GenAI (Tursunbayeva & Chalutz-Ben Gal, 2024). Creativity and a willingness to experiment as a form of exploratory learning (March 1991) can create learning loops like those realized within models such as the lean startup (Silva et al., 2020), leading to higher use of GenAI. Importantly, creativity involves heuristic rather than algorithmic forms of thinking (Amabile, 1988), meaning that more logic-based systems can be enhanced via human creativity, allowing startups to better face dynamic challenges typified by higher degrees of situational ambiguity (Mainemelis & Sakellariou, 2023).

Interestingly, proactivity is irrelevant, which may be suggestive of the unique characteristics that GenAI has as a GPT. For such technologies, the ability to understand, assimilate, and creatively apply them (represented by AC and creativity) may be more important than the speed of adoption (often associated with proactivity). The irrelevance of proactivity suggests a potential substitution effect between proactivity and the combination of AC and creativity. This effect could indicate that the ability to recognize, assimilate, and creatively apply external knowledge may be more crucial than the tendency to take initiative or be the first mover. This substitution effect challenges some views on technology use that emphasize proactivity’s importance (Dess et al., 1997). However, it aligns with perspectives on smart or fast follower strategies in technology adoption (Schnaars, 1994).

Startups may not necessarily be first movers, but their combination of AC and creativity may allow them to adopt and implement GenAI more effectively than their proactive counterparts. Notably, however, the irrelevance of proactivity does not necessarily make proactivity detrimental. Rather, in the presence of strong AC and creativity, the level of proactivity might not significantly influence the likelihood of high GenAI use. Startups following Pathway 4 are not just passive adopters of the technology, but active innovators who can creatively apply GenAI to solve problems and create value in their specific industry contexts.

Theoretical implicationsOur answer to our research question yields three core contributions to theory. First, an empirical contribution is made to the growing body of practical knowledge on technology use in startups. Given the limited research on startups in this domain, along with the growing emphasis on the importance of an AI-oriented strategic mindset, the potential benefits of such technologies for venture scaling, and the cognitive and material constraints startups typically face, we were particularly interested in exploring which characteristics of startups are associated with high GenAI usage.

The emergence of GenAI represents a transformative force for entrepreneurship, with many practical examples of its implementation; however, very little empirical work has focused on the characteristics of startups that adopt GenAI, their environments, and their usage patterns. Much work attends to larger more established companies (Oldemeyer et al., 2024). Firm size, type, and operating conditions are taken to have a strong bearing on organizational resources and capabilities to engage in innovative activities, therefore providing the grounding to study their use of GenAI (Mariani et al., 2023).

Ruokonen and Ritala (2024) have noted that the number of genuine “AI-first” companies remains relatively small and that AI, as a strategic and competitive resource, should be at the forefront of all business thinking, not just for larger corporations or those startups generating the AI technology itself. An “AI-first” strategy may vary across organizational types or even within archetypical organizational blueprints for a given sector (Baron & Hannan, 2002), but it arguably requires a proactive strategic leadership intent to seek information and knowledge, while creatively transforming and applying this knowledge through AI.

In this sense, our findings lend support to more practitioner-based work through emphasizing the importance of individual factors such as creativity and proactivity in high GenAI use. This focal point aligns with evidence on the strong influence of entrepreneurs and their attributes on the culture and operations of their emerging organizations, exacerbated during the initial phases of startup development (DeSantola & Gulati, 2017). Founders can cultivate an environment embracing the adoption and use of nascent technologies by demonstrating high levels of creativity or proactivity and supporting creativity and proactivity through foresight and the quick introduction of novel products and processes (Baron & Tang, 2011). We therefore reiterate the findings that proactivity and the ability to identify and seize opportunities are valuable entrepreneurial capabilities for leaders attempting digital transformation (Corvello et al., 2022).

However, individual attributes are insufficient, and digital tools need to be supported by dynamic capabilities informed by continuous learning and unlearning, combined with an openness to experimentation and change (Ghosh et al., 2022). Startups have learned that to achieve competitive advantage, they can combine innovative technologies with their capabilities (Mariani et al., 2023). Therefore, high GenAI use is a holistic concept urged to consider startup dimensions such as business models, strategies, processes, and capabilities (Kulkov, 2023; Vial, 2019). What follows is the capacity for GenAI to cause, but concurrently require, changes in startup operations and structures (Garzoni et al., 2020). Therefore, many startups struggle to integrate GenAI into their daily operations due to a mixture of individual ability, organizational learning, and environmental factors. Such struggles lead to our second contribution: the need for integrated approaches to the sociotechnical and microlevel dimensions of GenAI use (Arroyabe et al., 2024; Tursunbayeva & Chalutz-Ben Gal, 2024).

Startup processes are dynamic, involving interrelated causative factors limiting the possibility for precise predictions. Interactions between human agency, environment, and technological advancements amplify the complexity and demands of the founder role. Digital transformation, rather paradoxically, is argued to be to a lesser extent about the technology and more about people and talent (Frankiewicz & Chamorro-Premuzic, 2020). However, organizational factors cannot be disregarded, as technologies have impact across all levels. If startups are to keep pace, new ways of learning and skill acquisitions have to be encouraged.

Tursunbayeva and Chalutz-Ben Gal (2024) recommend that for the smooth and successful adoption of AI, various sociotechnical factors must be addressed. As argued elsewhere, digital technologies are not confined to an organizational focus and involve “individual, organizational, and societal contexts” (Legner et al., 2017, p. 301). Much literature on technology adoption assumes a static predictor-outcome approach whereby limited attention is designated to multilevel, causally asymmetric relations present within and across sociotechnical elements. We extend work on technology adoption that employs various models grounded in linearity and variable independence, such as the technology adoption model (Davis, 1989), and that centers mainly on the individual, by empirically demonstrating that various constellations of organization-led, individual-led, and environment-led conditions can raise GenAI use in accelerator-based startups.

Through a multilevel approach (Baron & Tang, 2011) aligned with the technology-organization-environment (T-O-E) framework (Tornatzky & Fleischer, 1990), we bridge a pressing void by exploring the complexity of GenAI use, considering interrelations between a selection of core individual and strategic factors from a digital transformation and organizational learning lens. We support work in entrepreneurship research that benefits from the application of organizational learning theory, a process concerned with knowledge acquisition, assimilation, and organization (Wang & Chugh, 2014).

The T-O-E framework has been widely applied to technology adoption studies at the organizational level within SMEs (e.g., Pool et al., 2015; Safari et al., 2015) and more recently for contemporary technologies such as AI and blockchain Almashawreh et al. (2024); Orji et al. (2020). However, focusing on startups allowed us to incorporate the holistic nature of technology adoption by framing it through a lens of complexity and organizational learning, representing a novel approach particularly well-suited to analyze levels of GenAI usage in startups (Schwaeke et al., 2024). Thus, our findings reveal a richer picture extending beyond the commonly studied outcomes of organizational learning (i.e., the action of GenAI use in startups) incorporating the processes or possible combinations of conditions that can result in this outcome (Woiceshyn, 2000).

Third, and finally, building on this configurational approach we contribute to the emerging literature requesting a more detailed focus on AI and entrepreneurship (Schwaeke et al., 2024). AI is becoming better understood through an economics-based lens (Cockburn et al., 2019), but calls have been made for deeper research at the organizational level (Mariani et al., 2023). We identify four distinct pathways to high GenAI use, each representing a unique configuration of creativity, proactivity, industry dynamism, and AC (see Table 5). Our findings reinforce the principles of conjunction, equifinality, and causal asymmetry in technology use (Fiss, 2011), demonstrating that different combinations of internal capabilities and external pressures can stimulate high GenAI use (Arroyabe et al., 2024).

Overview of Pathway Characteristics.

A notable feature across all pathways is the consistent presence of industry dynamism, aligning with the volatility of the startup process and highlighting the influential role of external environmental pressures beyond organizational and individual level factors in encouraging GenAI use (Cubric, 2020). The implementation of GenAI systems helps firms to augment their competitive position (Muhlroth & Grottke, 2022) in unstable environments and readjust their dynamic capabilities to suit their environments (Warner & Wäger, 2019), with internal capabilities decisive in GenAI adoption (Arroyabe et al., 2024). We afford a nuanced view to these contributions by demonstrating how industry dynamism, as an uncontrollable external factor, either alone or through interacting with internal startup factors in complex ways, can produce outcomes of high AI use. Thus, although internal aspects are especially important for digital transformation (Tursunbayeva & Chalutz-Ben Gal, 2024), we show that alone they are insufficient for high GenAI use in startups, and in some circumstances internal capabilities are not required.

In some pathways, the strong presence of industry dynamism appears to offset the absence or irrelevance of internal capabilities, highlighting causal asymmetry. Startups therefore display multiple characteristics supportive of high GenAI use, depending on their strengths and environmental conditions. The varying conditions across pathways, from a perceived forced usage and reactive adoption of exploiters (Pathways 1 and 3) to more balanced approaches combining external pressures with internal capabilities of combinators (Pathways 2 and 4), offering novel insights into the diverse characteristics of startups using GenAI and suggest that high GenAI use may not always be proactive and capability driven. Importantly, high usage of the latest technologies may not always be economically advantageous (e.g., Singla et al., 2024), so it can be more favorable to develop the capacity and skills permitting continuous innovation.

This finding urges careful consideration, due to the possibility for premature adoption and differences in startup readiness, in which the technology acts as a life support sustaining a startup which may be doomed to failure. In this respect, elements of an induced “digital Darwinism” (Goodwin, 2018) can be viewed, reflecting a natural selection excluding those failing to embrace new technologies and keep pace. Therefore, even without adequate infrastructure for successful implementation and understanding of new digital tools, startups may become seduced by potential benefits, by hype, or by acquiescence to legitimate prototypes; such startups lack the capacity for an extensive search to learn how GenAI could be effectively integrated and used. Pathways 1 and 3 are perhaps best perceived as merely incorporating GenAI use into startups rather than transforming their business models, which would result from learning and complementary assets (Schiuma et al., 2021). Startups and founders will need to continually modify their business models through action, with the recurrent challenge of renewal (Crossan et al., 1999).

On the other hand, GenAI may provide the functional and operational runway necessary for an emergent, vulnerable organization to combat early resource limitations and gain enough traction to determine the desirability, feasibility, and economic viability of their venture. Therefore, GenAI use can offer many perceived benefits, and these benefits need to be considered in view of longer-term repercussions, as it would be unproductive to continually invest scarce resources into a startup unlikely to achieve success. As the speed of technology continues rapidly, such pathways may signal cause for concern, as startups begin to extensively use the technology as a compensatory and substitution mechanism without having the organizational learning and human capital infrastructure in place to optimize its strategic usage.

For instance, GenAI can be complex for those unfamiliar with the technology, wherein the startup must absorb the associated complexities in constantly changing industry contexts. For this reason, many startups will engage in lean product development processes and absorb complexity via short iterative cycles of experimentation (Ghosh et al., 2022; Kerr et al., 2014). AC has traditionally been viewed as critical for technology adoption (Zahra & George, 2002), with robust knowledge management processes considered essential in AI use because they allow firms to contend with rapidly changing environments (Tursunbayeva & Chalutz-Ben Gal, 2024); nevertheless, our findings show that the importance of AC varies across pathways. In some configurations, high AC is indeed crucial for GenAI adoption; in others, it is either absent or irrelevant, suggesting that under certain conditions, startups are high users of GenAI without strong AC.

This finding contributes to ongoing debates about the role of AC in rapidly changing technological settings (Volberda et al., 2010) and indicates the need for greater complexity in understanding its function, especially in the context of emerging, democratized technologies. The emergent nature of the technology mean that its features and functionality are in constant flux (Bailey et al., 2022), suggesting that such startups may be hampered in its successful deployment over the longer term. Furthermore, startups are unlikely to benefit from expertise across all entrepreneurship process areas and therefore may need to look beyond their internal boundaries to source this knowledge (Rajaram & Tinguely, 2024), with AC as a mechanism facilitating this process of knowledge acquisition.

This asymmetry of presence continues with both creativity and proactivity, offering notable insights into the heterogeneous nature of GenAI use while casting some doubt on their universal importance for technology use (e.g., Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). We find that the relevance of these factors depends on the specific configuration of conditions facing the startup. Interestingly, we found no pathway containing both creativity and proactivity together. This lack of correspondence was surprising, as early adopters of new technologies who are digitally oriented and have a digital vision for continuous transformation can often command higher profits through their early and creative implementation.

Practical implicationsStartups often lack a wide repertoire of complementary resources and capabilities that can facilitate the effective use of GenAI, including human capital and technological infrastructure. GenAI use for startups can be beneficial due to its ability to substitute and complement other factors, meaning that startups may no longer need to invest heavily in physical and human resources. Caution is advised, nonetheless, as associated learning curves and implementation costs of GenAI use can be high. Paradoxically, although GenAI can fill functional, personal, and capability voids, a skills deficit may be inadvertently created if founders and startup teams neglect to develop their own skills and expertise, undermining the long-term performance and sustainability of a startup for short-term gains. For instance, if externally pressured into adopting GenAI, startups may not be prepared for its effective implementation, meaning that it may even hinder performance.

Leveraging GenAI may be tempting, as it can produce swift, affordable, and highly detailed outputs of novel ideas. However, the extensive reliance on such technology poses challenges, as the nuanced decision-making and critical thinking skills of managers remain irreplaceable, with critical expertise required for the effective adoption of AI systems in short supply (Chui et al., 2018). A full-scale shift to a GenAI-driven startup may encounter obstacles, particularly if the development of key human capabilities, such as creativity and proactivity, are overlooked. Using GenAI comprehensively presents significant difficulties, as it requires adaption to an evolving environment.

This process involves acquiring fresh expertise and knowledge, developing innovative operational strategies, and integrating advancements into existing processes, all benefiting from high levels of AC. Overwhelmed and strained leadership might struggle to acquire the necessary expertise to understand emerging offerings, leading to poorly informed choices that are challenging to reverse and can often result in unfavorable outcomes. Knowledge of how GenAI is and can be applied (Oldemeyer et al., 2024) supports effective GenAI use. While GenAI can automate workflows, full automation of interconnected tasks is rare. Additionally, the scope of GenAI-generated solutions is often limited by the algorithms selected by humans. If specifications are too vague, the outcomes, especially in generative design, can be overly “creative” and impractical. This pitfall necessitates human knowledge and oversight.