Quality in healthcare encompasses three main dimensions: clinical effectiveness, safety, and patient-centred care. The patient experience can be defined as the sum of all the interactions during a visit to or stay at a healthcare facility, produced by the culture of the organisation, that influence the patient's perceptions throughout the continuum of the care process.1 It is a totally subjective concept, since it encompasses the patient's perceptions, thoughts and feelings when they come into contact with the healthcare world.2 Therefore, the participation of patients and their caregivers or relatives is absolutely necessary to develop strategies for improvement.1,2

Most studies on paediatric populations are based on the caregivers’ opinion, although recent studies have proven that adolescents’ experience is less dependent on adults than that of younger children, and that they are both valid and reliable reporters on certain aspects of preventive services.3

Moreover, research in patient experience can be carried out using a qualitative methodology. In the studies by Berry et al.4 and Truter et al.5 about the decision to seek care in the PED for non-urgent conditions, this methodology has been found to be useful to explore the patients’ experiences in the PED. It gives them a voice, taking their perspectives into account and placing them at the centre of the research, and it offers a structured way to explore any potential for further interventions. This is why we performed a study which aimed to describe the patient experience among adolescents in the PED, and to identify the factors that affect it.

We carried out a qualitative descriptive study between September 2021 and January 2022 in a highly complex urban paediatric hospital.

We included patients aged 12–17 years who were attended to in the PED. Patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit, those who were unable to answer the questions and those who declined to participate were excluded. Psychiatric patients were also excluded, as they received a different care approach (specific circuit) in our PED.

At the time of discharge from the PED, a semi-structured interview was conducted. Patients were selected using quota sampling (age, sex, triage level and specialty) based on the demographics of the patients seen in the previous year (2020–2021).

A questionnaire was designed based on previous studies concerning patient experiences in the PED.6–9 This non-validated questionnaire was composed of 31 open-ended questions about general aspects (4 questions), the arrival at the PED (4 questions), the triage process (5 questions), the wait (9 questions) and, finally, the visit itself (9 questions).

The patient experience was analysed following a qualitative methodology, which can be divided into 4 main phases:

- 1.

Obtaining the information (semi-structured interviews).

- 2.

Capture and transcription (interviews were audio taped and transcribed verbatim).

- 3.

Analysis (the information was organised into observations; repeated observations were eliminated).

- 4.

Codification and integration of information (observations were coded into categories and subcategories (based on their topic); they were also classified into positive, neutral, and negative observations. All the observations were finally integrated, creating two archetypes (that is, a very typical example of a particular person or a thing)).

During the study period, 36 adolescents were interviewed; 324 observations were collected; 175 redundant observations were eliminated, obtaining 149 observations in the end.

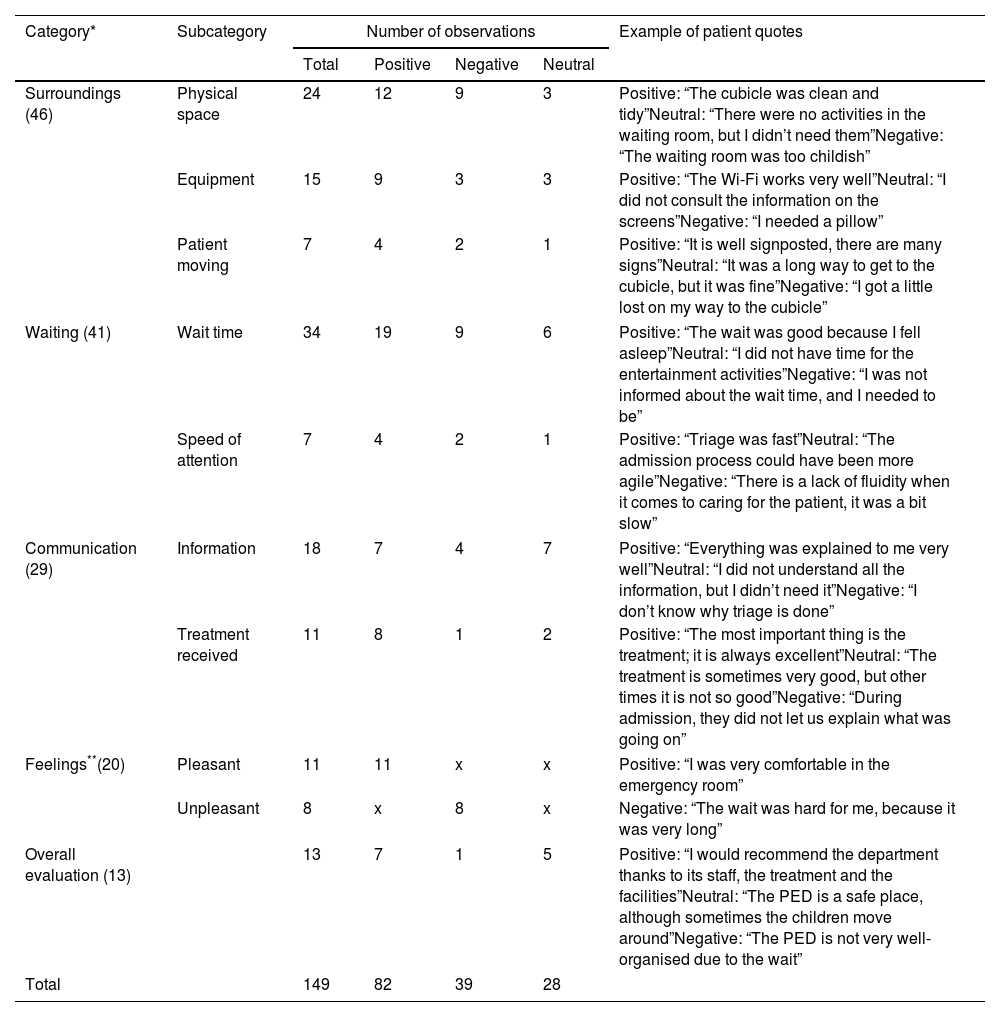

Those 149 observations were analysed and classified firstly into 5 main categories: environment (46 observations), waiting (41 observations), communication (29 observations), feelings (20 observations), and global evaluation (13 observations). Each main category was divided into several subcategories. After that, the observations were classified into positive, negative, and neutral. Table 1 shows the categories/subcategories, positive/neutral/negative observations with the total number of each type of observation, and some examples of each one.

Codification of the observations.

| Category* | Subcategory | Number of observations | Example of patient quotes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Positive | Negative | Neutral | |||

| Surroundings (46) | Physical space | 24 | 12 | 9 | 3 | Positive: “The cubicle was clean and tidy”Neutral: “There were no activities in the waiting room, but I didn’t need them”Negative: “The waiting room was too childish” |

| Equipment | 15 | 9 | 3 | 3 | Positive: “The Wi-Fi works very well”Neutral: “I did not consult the information on the screens”Negative: “I needed a pillow” | |

| Patient moving | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 | Positive: “It is well signposted, there are many signs”Neutral: “It was a long way to get to the cubicle, but it was fine”Negative: “I got a little lost on my way to the cubicle” | |

| Waiting (41) | Wait time | 34 | 19 | 9 | 6 | Positive: “The wait was good because I fell asleep”Neutral: “I did not have time for the entertainment activities”Negative: “I was not informed about the wait time, and I needed to be” |

| Speed of attention | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 | Positive: “Triage was fast”Neutral: “The admission process could have been more agile”Negative: “There is a lack of fluidity when it comes to caring for the patient, it was a bit slow” | |

| Communication (29) | Information | 18 | 7 | 4 | 7 | Positive: “Everything was explained to me very well”Neutral: “I did not understand all the information, but I didn’t need it”Negative: “I don’t know why triage is done” |

| Treatment received | 11 | 8 | 1 | 2 | Positive: “The most important thing is the treatment; it is always excellent”Neutral: “The treatment is sometimes very good, but other times it is not so good”Negative: “During admission, they did not let us explain what was going on” | |

| Feelings**(20) | Pleasant | 11 | 11 | x | x | Positive: “I was very comfortable in the emergency room” |

| Unpleasant | 8 | x | 8 | x | Negative: “The wait was hard for me, because it was very long” | |

| Overall evaluation (13) | 13 | 7 | 1 | 5 | Positive: “I would recommend the department thanks to its staff, the treatment and the facilities”Neutral: “The PED is a safe place, although sometimes the children move around”Negative: “The PED is not very well-organised due to the wait” | |

| Total | 149 | 82 | 39 | 28 | ||

From these results, two patient profiles (archetypes) were created. The archetype with a positive patient experience in the PED is that of a male adolescent, who has a low triage priority level and waits for a short time. He considers the waiting room to be comfortable, understands his triage level, and he perceives the waiting time as acceptable. He entertains himself with the television, with his mobile phone, or by talking with his companion (usually the mother). He appreciates the friendliness of the staff and the explanations given.

The archetype with a negative patient experience in the PED is that of a female adolescent, with a low triage priority level and who waits for a long time (usually more than 2h). She does not understand why triage is done and does not know her triage level, complains about the long wait time, the lack of information on the screen, and she feels bored during the waiting time. She says there are too many people in the waiting room, with little social distance (feeling at risk for being infected), and that it is too noisy. She complains about the slow processes in the PED.

The experience of adolescent patients is generally positive, as evidenced by the mostly positive observations throughout the patient journey in our PED, from the entry until discharge. These findings are also supported by other quantitative studies. As an example, Shefrin et al.7 described a good patient experience among the adolescents seen in the PED and they found some negative aspects, such as wait time and the characteristics of the waiting area. But to our knowledge, this is the first published study about the adolescent patient experience in the PED that has used a qualitative research approach and therefore, it is able to thoroughly describe their emotions, expectations, and needs.

The creation of archetypes has allowed for identifying how this patient experience is formed. On one hand, the patient with a positive experience is a boy that has not waited too long and that has felt comfortable in the waiting area; he positively values his communication with the health staff and he feels listened to and cared for in the PED. In a similar way, multiple authors have pointed out the importance of communication with an adolescent patient who wants to be treated as an adult, not as a child.7–9

On the other hand, the negative experience archetype has shown that an excessively long wait time in a noisy waiting area without entertainment activities, a misunderstanding of how triage levels work, and slow processes give rise to a bad experience in our PED. Other studies have found similar results7,10: Rutherford et al. found that a wait time exceeding 3h worsened the patient's rating of overall care in the PED.

In this sense, while it is true that the wait time depends on multiple factors (number of patients seeking care, complexity of the pathology, number and professional experience of the PED staff, structure of the PED itself, etc.) and some of these factors are out of our control, improving the waiting experience is possible. In this sense, making sure patients understand the triage level concept is essential, as they will probably better accept their wait time or they will at least have realistic expectations about it. Another related aspect that can be improved is the information provided during the wait: it is important for patients to know the estimated wait time according to their triage level, and this information can be shown, for example, on screens in the waiting area. Implementing a patient calling system could improve the patients’ experience because they could wait in other areas. In fact, in our PED, patients are allowed to wait outside of the waiting area if they have installed an app on their mobile phones that alerts them when they are to be seen.

The waiting area itself is also important. As other authors have previously pointed out, adolescents have unique needs and they usually want their own space, separated from the space of younger children, with their own entertainment activities.7 In our study, they expressed special appreciation for a good Wi-Fi connection and they entertained themselves with television or with their mobile phones. Thus, it is particularly important to ensure that there is good Wi-Fi and charging points for mobile phones and tablets. In addition, this time spent in the waiting area could be used to teach or inform them about health issues, for example.

Overall, the patient experience for adolescents in our PED is positive. Adolescents highlight the communication and friendliness of the staff as especially positive points. One of the most important aspects that gives rise to a negative experience is the wait time and the waiting environment, so it is advisable to develop strategies to improve this part of the patient journey. Research that includes the patients’ point of view allows us to identify important aspects that could be missed and that need to be improved to offer better patient care.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Cristina Parra, Mónica Boada, Anna Rojas and Agustina Agustina Pallache. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Monica Boada and Cristina Parra and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical approvalThis study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Fundació Sant Joan de Déu – University of Barcelona (08/07/2021/PIC-141-21).

FundingThe authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.