Nurses, as the largest group of health professionals, are at the frontline of the healthcare system in response to COVID-19 epidemic. This study aimed to evaluate the nurses’ certainty and satisfaction with medical gloves when exposed to coronavirus in Fars province, south of Iran.

MethodsUsing convenience sampling, 400 hospital nurses during the COVID-19 outbreak were selected from eight hospitals of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (SUMS). A questionnaire about glove reliability, including protection in tasks, durability, integrity and tear resistance, feeling fearful, and focusing on duties, and the nurses’ anxiety regarding their infection with coronavirus was distributed to the selected nurses to complete. 375 questionnaires were completed (response rate of 93.75%). Among the participants, 180 (48%) were in the corona section and 195 (52%) were hardly possible to have contact with coronavirus pneumonia patients.

ResultsThe mean score (SD) of anxiety about infection with COVID-19 for nurses in the COVID-19 section and those in the non-COVID-19 section were 6.08 (2.8) and 4.56 (2.58), respectively (p<0.05). The mean duration of gloves usage in a day was almost similar in the two groups (about 5h), but the number of glove replacements was significantly higher among the nurses in the corona section (6 times) compared to those in the non-corona section (3 times). The two groups were also significantly different regarding glove protection in daily tasks and glove durability.

ConclusionThe nurses in the corona section had more concerns about medical gloves as a type of personal protective equipment. In addition to health education on controlling and preventing the spread of diseases, raising awareness about the reliability of personal protective equipment can improve nurses’ performance.

Las enfermeras, como el grupo más grande de profesionales de la salud, están en la primera línea del sistema de salud en respuesta a la epidemia de COVID-19. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo evaluar la certeza y satisfacción de las enfermeras con los guantes médicos cuando se exponen al coronavirus en la provincia de Fars, al sur de Irán.

MétodosUtilizando un muestreo de conveniencia, se seleccionaron 400 enfermeras de hospital durante el brote de COVID-19 de ocho hospitales de la Universidad de Ciencias Médicas de Shiraz (SUMS). Se distribuyó a las enfermeras seleccionadas un cuestionario sobre la confiabilidad de los guantes, que incluye protección en las tareas, durabilidad, integridad y resistencia al desgarro, sensación de miedo y concentración en las tareas, y la ansiedad de las enfermeras con respecto a su infección por coronavirus. Se completaron 375 cuestionarios (tasa de respuesta del 93,75%). Entre los participantes, 180 (48%) se encontraban en la sección COVID-19 y a 195 (52%) les era difícilmente posible tener contacto con pacientes con neumonía por coronavirus.

ResultadosLa puntuación media (DE) de ansiedad por la infección con COVID-19 para las enfermeras en la sección COVID-19 y las de la sección no COVID-19 fue de 6,08 (2,8) y 4,56 (2,58), respectivamente (p <0,05). La duración media del uso de guantes en un día fue casi similar en los dos grupos (aproximadamente 5 h), pero el número de reemplazos de guantes fue significativamente mayor entre las enfermeras de la sección COVID-19 (6 veces) en comparación con las de Sección COVID-19 (3 veces). Los dos grupos también fueron significativamente diferentes con respecto a la protección de los guantes en las tareas diarias y la durabilidad de los guantes.

ConclusiónLas enfermeras de la sección COVID-19 tenían más preocupaciones sobre los guantes médicos como un tipo de equipo de protección personal. Además de la educación sanitaria sobre el control y la prevención de la propagación de enfermedades, la sensibilización sobre la fiabilidad del equipo de protección personal puede mejorar el desempeño de las enfermeras.

Epidemics and pandemics, such as the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), have enormous implications on healthcare systems, especially on the workforce.1,2 Preliminary reports from COVID-19 have indicated a high rate of infection in healthcare professionals.3 Nurses, as the largest group of health professionals, are at the frontline of the healthcare system in response to COVID-19 epidemic,4 deliver care directly to patients at close physical distances and, as a result, are often directly exposed to these viruses and are at high risk of diseases.5,6

In Iran, out of the 110,000 nurses employed, about 65,000 provided care for patients directly during the COVID-19 crisis, 50% of whom worked in hospitals uninterrupted for two weeks to two months without seeing their families. Moreover, 17,000 nurses were infected with COVID-19, many of whom recovered during the illness, but 40 ones died unfortunately.7–9

Nurses are required to protect themselves and prevent the transmission of the disease in healthcare settings. Precautions taken by healthcare workers for patients with COVID-19 include the use of appropriate personal protective equipment including N95 respirators, facemasks or eye protections, isolation gowns, and medical disposable gloves.10 The world health organization (WHO) and other national and international public health authorities have also recommended the implementation of safety protocols for healthcare workers including isolating patients, restricting the number of personnel entering isolation areas, and protecting workers in close contact with the sick person by using additional engineering and administrative controls, safe work practices, and personal protective equipment.11–14

Despite all the arrangements, stress and anxiety regarding the infection caused a destructive psychological load which can lead to mental disorders, weakening the immune system and reducing the body's ability to fight disease in nurses.15 Furthermore, the risk of being infected, transmission to family members, feeling inferior to the vulnerabilities of their job, and restrictions on personal freedom have been reported as the major concerns of nurses.6,16,17 Mental health problems observed among nurses during COVID-19 and previous international health crises, such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), included sleep disturbance, stress, anxiety, and fear of infection.2,18 In Hong Kong, Lee et al. found that healthcare workers had higher levels of post-traumatic stress, depression, and anxiety compared to non-health care workers a year after the outbreak of SARS.18 A study conducted in China also demonstrated that a significant number of healthcare workers who treated COVID-19 patients suffered from depression, anxiety, insomnia, and distress.19 Moreover, Badahdah et al. showed that both stress and anxiety had a strong effect on the overall well-being of healthcare workers.20 The reason for the more complicated situation during epidemics is the logistical issues related to personal protective equipment.21

It seems mental health problems resulting from COVID-19, increase nurses’ dissatisfaction with personal protective equipment, such as medical gloves. Sarboozi et al., found that there was a significant relationship between anxiety and satisfaction of personal protective equipment.22 However, no study has been conducted on this issue directly. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the effects of COVID-19 conditions on nurses’ uncertainty about the proper protection of medical gloves, as a type of personal protective equipment, against COVID-19.

MethodsStudy design and participantsThis was a cross-sectional study conducted in Fars province, south of Iran.

Sample sizeThe total population of nurses in hospitals of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences was 7726. According to Eq. (1) for calculating the sample size,23 we reached 365, and considering the possible falls and to increase the accuracy, finally 400 nurses were selected.

where n is the sample size, N is the population size, z is the value corresponding to the level of confidence required, s is the standard deviation (equal to 0.5) and d is precision (in proportion of one; if 5%, d=0.05).Selected sampleUsing convenience sampling, 400 hospital nurses during the prevalence of COVID-19 were selected from eight hospitals of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (SUMS). 200 nurses were form the COVID-19 sections and 200 nurses were form the non-COVID-19 sections. The nurses entered the study if they were working in one of these eight hospitals in Fars province, during the outbreak of COVID-19. In addition, as the study instrument was an electronic questionnaire, the nurses responded to the questionnaire if they had access to the electronic platform. Also, the incomplete questionnaires were excluded from the study.

InstrumentThe questionnaire was divided into three different parts. The first part included demographic data of the participants (gender, age, work experience, education level, type of used gloves, duration of glove usage per day, and number of glove replacements in one shift). Based on the study of Nemati et al., the second part evaluated the nurses’ anxiety regarding their infection with COVID-19.24 The participants rated their anxiety regarding their infection (scoring from 1 to 10). The Medical Glove Assessment Tool (MGAT) developed by Zare et al.25 was used for evaluating nurses’ uncertainty about the proper protection of medical gloves in third part of the survey. This tool has 6 domains including tactile sensation, dexterity, grip strength, fitting, reliability, and hand hygiene. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.82. In the reliability domain, questions were asked about the ensuring the performance of gloves (durability, integrity, safety relief). The participants answered these specialized questions by three options of yes, no, and I do not know (see Appendix). At the beginning of the questionnaire, it was explained that participants should use the “I do not know” option when they are not sure about the answers, which is actually equivalent to “I am not sure”.

Data collectionData were collected from 22 to 29 June 2020. To prevent COVID-19 transmission through direct contact, we used a software to design our questions in the form of a web-based questionnaire. Data collection was conducted through social media and the questionnaire link was available for the participants using the online platform of WhatsApp. Participation in this study was voluntary. The participants were able to complete the survey only once and were allowed to terminate the survey at any time they desired. It should be noted that the survey was anonymous and confidential. The consent and ethical approval was placed at the beginning of the web-based questionnaire. An introductory paragraph outlining the purpose of the study was also posted along with the survey.

Ethics approval and consent to participateParticipation in the study was completely voluntary, and subjects were free to refuse to participate in the study or to leave the study at any time (without altering the behavior of researchers and hospital management). The consent we obtained from study participants was written. The consent was placed at the beginning of the web-based questionnaire. If the participants chose the “I agree” option, they would enter the first part of questionnaire. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (IR.SUMS.1399.107).

Data analysisThe data were analyzed using the SPSS 22 software and descriptive and analytical results were presented. Considering the non-parametric nature of the data, Mann–Whitney test and chi-square test were used for analysis. T-test was used to compare differences between groups. The significance level for performing statistical tests was less than 0.05 (p<0.05).

ResultsParticipants’ characteristicsOut of 400 questionnaires sent to the participants, 375 questionnaires were completed and the response rate was 93.75%. In total, 120 males and 255 females (60 males and 120 females in the COVID-19 section, and 60 males and 135 females in the non-COVID-19 section) completed the questionnaire. The means (SD) of age and work experience of the nurses were 34.73 (7.2) and 9.91 (7.61) years, respectively.

All participants used latex examination gloves. The descriptive results showed that the mean (SD) of glove use per day was 5.32 (3.54)h and the median of glove replacements in a work shift was four times. The results revealed no significant difference between the two groups regarding age, work experience, and level of education.

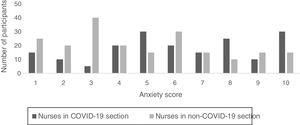

Anxiety about the infectionFig. 1 shows the data of the participants’ self-report of anxiety about the infection. The mean anxiety score (SD, 95% confidence interval) for nurses in the COVID-19 section and those in the non-COVID-19 section were 6.08 (2.8, 5.8–6.36) and 4.56 (2.58, 4.3–4.82), respectively. The nurses’ anxiety about their infection with COVID-19 in nurses in the COVID-19 section was significantly higher than those in the non-COVID-19 section (p=0.009).

Uncertainty about the medical glovesThe results indicated that 41.3% of the participants said that gloves protected them well, and most participants (53.3%) did not know if gloves protected them well in the tasks with a high risk of infection. Additionally, 150 nurses (40%) believed that the gloves did not have a good tear resistance. However, 54.7% of the participants felt less afraid of dangers and 62.7% of them could focus well on their duties while wearing gloves. The special items of the questionnaire and descriptive results among the participants have been presented in Table 1.

The descriptive results among the participants (n=375).

| Qualitative questions | Answers | No. (%) | 95% CI* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do gloves protect your hands well when performing daily tasks? | Yes | 155 (41.3) | (36.32, 46.28) |

| No | 95 (25.3) | (20.90, 29.70) | |

| I don’t know | 125 (33.3) | (28.53, 38.07) | |

| Do gloves protect your hands well when performing tasks with a high risk of infection? | Yes | 80 (21.3) | (17.16, 25.44) |

| No | 95 (25.3) | (20.90, 29.70) | |

| I don’t know | 200 (53.3) | (48.25, 58.35) | |

| Do gloves have good durability in the face of dangers? | Yes | 140 (37.3) | (32.41, 42.19) |

| No | 100 (26.7) | (22.22, 31.18) | |

| I don’t know | 135 (36) | (31.14, 40.86) | |

| Do gloves have good tear resistance? | Yes | 125 (33.3) | (28.53, 38.07) |

| No | 150 (40) | (35.04, 44.96) | |

| I don’t know | 100 (26.7) | (22.22, 31.18) | |

| Do you feel less afraid of dangers when you wear gloves? | Yes | 205 (54.7) | (49.66, 59.74) |

| No | 45 (12) | (8.71, 15.29) | |

| I don’t know | 125 (33.3) | (28.53, 38.07) | |

| Can you focus well on your duties when you wear gloves? | Yes | 235 (62.7) | (57.81, 67.59) |

| No | 40 (10.7) | (7.57, 13.83) | |

| I don’t know | 100 (26.7) | (22.22, 31.18) | |

The analytical results of the questionnaire items in the two groups have been depicted in Table 2. Accordingly, the mean duration of gloves usage in a day was almost similar, but the number of glove replacements was significantly higher among the nurses in the COVID-19 section in comparison to those in the non-COVID-19 section.

The analytical results of the questionnaire in the two study groups.

| Items | COVID-19 section | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Duration of gloves usage in a day (h)Mean (SD) | 5.39 (3.77) | 5.26 (2.54) | 0.885 | |

| Glove replacements in one shift (No.)Median | 6 | 3 | <0.001* | |

| Protection in daily tasksNo. (%) | Yes | 35 (19.4) | 120 (61.5) | 0.001** |

| No | 60 (33.3) | 35 (17.9) | ||

| I don’t know | 85 (47.2) | 40 (20.5) | ||

| Protection in tasks with a high risk of infectionNo. (%) | Yes | 20 (11.1) | 60 (30.8) | 0.074 |

| No | 60 (33.3) | 35 (17.9) | ||

| I don’t know | 100 (55.6) | 100 (51.3) | ||

| DurabilityNo. (%) | Yes | 30 (16.7) | 110 (56.4) | <0.001** |

| No | 80 (44.4) | 20 (10.3) | ||

| I don’t know | 70 (38.9) | 65 (33.3) | ||

| Tear resistanceNo. (%) | Yes | 55 (30.6) | 70 (35.9) | 0.061 |

| No | 95 (52.8) | 55 (28.2) | ||

| I don’t know | 30 (16.7) | 70 (35.9) | ||

| Feeling fearfulNo. (%) | Yes | 85 (47.2) | 120 (61.5) | 0.347 |

| No | 30 (16.7) | 15 (7.7) | ||

| I don’t know | 65 (36.1) | 60 (30.8) | ||

| Focus on dutiesNo. (%) | Yes | 115 (63.9) | 120 (61.5) | 0.818 |

| No | 15 (8.3) | 25 (12.8) | ||

| I don’t know | 50 (27.8) | 50 (25.6) | ||

The results showed significant differences between the two groups concerning glove protection in daily tasks and glove durability. Only 35 nurses in the COVID-19 section believed that the gloves certainly protected their hands in daily tasks. The positive answer to this question was mostly among the nurses of the non-COVID-19 section, and the nurses of the COVID-19 section either gave negative answers or did not know whether the gloves protected them well during daily tasks. Nonetheless, considering the tasks with a high risk of infection, most nurses in both groups were not sure about the protection of gloves.

Considering durability, most non-COVID-19 nurses gave positive answers, while most of those in the COVID-19 section gave negative answers. The number of participants who did not know the durability of gloves in risky situations was equal in the two groups. Furthermore, no significant difference was found between the two groups with respect to tear resistance of gloves. However, a larger number of nurses in the COVID-19 section believed that gloves were not resistant to tearing. 47% of nurses in the COVID-19 section and 61% of nurses in the non COVID-19 section felt less afraid of dangers while wearing gloves. Also, 64% of nurses in the COVID-19 section and 62% of nurses in the non COVID-19 section focused well on their duties while using gloves. However, there was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to feeling fearful and focus on duties.

DiscussionIn this study, an attempt was made to investigate the psychological effects of COVID-19 pandemic on the reliability of medical gloves among nurses. Similar to the results of other studies, the participants of this study that work in the COVID-19 section of the hospital have a higher level of anxiety about their infection than the other nurses.20,26,27 Based on the findings of previous studies, a lack of perceived psychological preparedness, perceived self-efficacy to help the patients, family support; greater perceived stress; or having poor sleep quality were associated with both elevated depressive and anxiety symptoms. Lacking knowledge about COVID-19, higher education attainment, having family or friends infected with the virus were also associated with elevated anxiety symptoms.26

The results showed that more nurses in the COVID-19 section were skeptical compared to other nurses about the power of protection, the ability to create appropriate barriers, and the durability of medical gloves. Accordingly, the number of positive answers was significantly lower in the COVID-19 nurses compared to the other group. However, regardless of the nurses’ workplace or the pandemic, the use of gloves makes them feel safe, reduces their fears, and increases their concentration on the work. These results are consistent with the findings of the Sarboozi et al.22 They found that nurses who scored lower on personal protective equipment were more anxious. Regarding this finding, it can be said that satisfaction with personal protective equipment is one of the effective and necessary factors that can be considered as a source of anxiety in nurses.22

The nurses’ uncertainty was clear by answering with the “I don’t know” and “No” options. Many nurses in the COVID-19 section chose the ‘I don’t know’ answer with uncertainty about the effectiveness of medical gloves. Based on the previous studies, there was also uncertainty about other personal protective equipment such as face masks.28 Nurses’ uncertainty about their fear of working with gloves and their concentration was also one of the interesting results of the study, which showed that participants were unsure about the safe operation of medical gloves. Up to now, some studies have been conducted on the psychological status of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.29–31 The results of these studies demonstrated that the medical staff working in the departments with close contact with coronavirus pneumonia patients, such as the respiratory department, emergency department, intensive care unit, and infectious diseases department, suffered from more psychological disorders and had almost twice higher risk of suffering from anxiety and depression compared to the clinical staff with the low possibility to have contact with coronavirus pneumonia patients.29 This might be the reason for uncertainty about medical gloves (choosing “I don’t know” or “No” options). The results of the present study showed that working in the COVID-19 section significantly increases anxiety levels. On the other hand, it was found that nurses in the COVID-19 section have less confidence in the optimal performance of medical gloves. These higher stress and anxiety levels may make nurses hesitant about the efficacy of personal protective equipment like medical gloves. Therefore, it can be argued that the psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic had led nurses to be unsure about the effectiveness of medical gloves, which is why they chose the “I do not know” option more.

For frontline clinician, safety is one of the most important concerns that can be achieved through the use of personal protective equipment.32 One of the COVID-19 concerns at this level is the fear of personal safety around infection and lack of adequate or inefficient personal protective equipment.27 The current study results indicated that the nurses in the COVID-19 section had more concerns about medical gloves as a type of personal protective equipment. The number of glove replacements in one shift was also significantly higher in this group compared to the other group. Excessive use of personal protective equipment can cause a shortage of them and cause problems. Based on the study of Ahmed et al., about 160 (46%) Pakistani participants felt like quitting their job due to lack of PPE, which was higher than the response from the US doctors, 72 (31.9%) of which responded affirmatively. Because the majority of doctors in their study reported being scared of the current situation and feared that they might transmit the infection to their loved ones.33 It can be considered that the psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic occur in different ways. Psychological stress, lack of protective equipment, fear of inefficiency is all related.34

It is universally known that COVID-19 is highly infectious and spreads rapidly, imposing a significantly increased workload on frontline health workers. Direct contact with confirmed patients, lack of protective equipment, suspected patients with a hidden medical history, and unknown behavior of the virus can increase the risk of being infected.29 In addition, healthcare workers are afraid of taking the virus to their families and the inability to cope with critical patients. The greater the number of obstacles they experience, the more they may feel unable to achieve their aspirations. The resulting strain may, in turn, be internalized and create anxiety and depression,35 which can affect the healthcare workers’ uncertainty about the effectiveness of personal protective equipment. Hence, in addition to health education on controlling and preventing the spread of the disease and psychological counseling, raising awareness about the reliability of personal protective equipment can help reduce the psychological load of epidemics among nurses.

The present study had several limitations. One limitation was that the participants were just from the hospitals of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. Secondly, it was a cross-sectional study and did not follow a representative selection method. Thus, caution should be practiced in generalizing the results to all nurses in Iran. Moreover, since this study was the only research in this field, comparison of the results was not possible. Hence, further studies with larger sample sizes are recommended to be conducted in this area. In addition, in this study, only one of the personal protective equipment was examined. It is suggested that future research examine nurses’ uncertainty in the use of protective masks, gowns, and gloves and pay more attention to the reasons that can increase nurses’ uncertainty.

ConclusionThe current study results indicated that the nurses in the COVID19 section unfolded greater uncertainty about the efficacy of medical gloves in comparison to other nurses. This lack of trust in personal protective equipment can increase psychological problems among healthcare workers, especially nurses. Thus, effective strategies toward the improvement of mental health should be provided for these individuals. For example, raising awareness about the effectiveness of personal protective equipment through occupational health education can help improve the nurses’ mental state. Management’ efforts to provide high quality personal protective equipment and attention to nurses’ opinions can also be effective in reducing their anxiety. Medical centers, especially those receiving COVID-19 patients, have also been suggested to provide counseling services to healthcare workers including how to control stress. Similarly, healthcare providers need to be cognizant of their specific symptoms of mental health issues and seek help.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article was extracted from a part of the dissertation written by Asma Zare, PhD candidate of Occupational Health Engineering, and was financially supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (No. 20843). The authors would like to acknowledge the support and assistance provided by all participants. They would also like to thank Ms. A. Keivanshekouh at the Research Improvement Center of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for improving the use of English in the manuscript.